Abstract

In 1994, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) initiated a program to address communication gaps between community residents, researchers and health care providers in the context of disproportionate environmental exposures. Over 13 years, together with the Environmental Protection Agency and National Institute for Occupational Health and Safety, NIEHS funded 54 environmental justice projects. Here we examine the methods used and outcomes produced based on data gathered from summaries submitted for annual grantees' meetings. Data highlight how projects fulfilled program objectives of improving community awareness and capacity and the positive public health and public policy outcomes achieved. Our findings underscore the importance of community participation in developing effective, culturally sensitive interventions and emphasize the importance of systematic program planning and evaluation.

IN THE LATE 1980S, THE ENVI-ronmental justice movement emerged to address the disproportionate burden of environmental exposures on low-income and minority communities.1,2 Concerned communities raised awareness of the myriad environmental and health issues they faced and called for the federal government to respond.3 In 1993, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) held a 2-day workshop on research needs to address environmental justice and equity that generated recommendations including the need to engage community groups in the research discussion.4,5 In 1994, 6 government agencies with the support of community and academic leaders convened the first federal environmental justice symposium, Health Research and Needs to Ensure Environmental Justice, to seek recommendations by community leaders, workers, business and academic representatives, diverse government personnel, and the broader scientific community. One key recommendation was improving communication and trust among partners.3,6

In response, NIEHS issued the first of many funding announcements, Environmental Justice: Partnerships for Communication. Subsequently joined by the EPA and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), Partnerships for Communication became a 13-year interagency program, funding 54 projects addressing a wide spectrum of environmental and occupational exposures across communities both urban and rural (Table 1).7 Projects were funded for 4 years (with reapplication possible) at $150 000 to $200 000 annually (direct costs) and required the collaboration of 3 partners: a research organization, a community-based organization, and a health care–provider organization. The 54 projects were funded separately by the agencies, but the program was coordinated as an interagency initiative through the use of a common project summary form and an annual grantees' meeting during which scientific progress was shared.

TABLE 1.

Projects Funded by the NIEHS, NIOSH, and EPA Under the Partnerships for Communication Program: 1994–2007

| Project Title | Issue | Population | Lead Organization | Dates |

| Akwesasne First Environment Communications Program | Environmental contamination | Native Americans | CBO | 1994–2003 |

| Southeast Los Angeles Environmental Health Project | Environmental contamination | Latinos | CBO | 1994–2003 |

| Risk Management In Native American Communities | Radiation | Native Americans | University | 1994–2003 |

| Environment Justice Partnership For Communication | Air and water pollution | African Americans | University | 1995–1999 |

| Richmond Laotian Environmental Justice Collaboration | Lead, toxic emissions, fish contamination | Laotians | CBO | 1995–1999 |

| Community Responsive Partners For Environmental Health | Hazardous waste and pesticides | African Americans and farmworkers | CBO | 1995–1999 |

| Southeast Asian Environmental Health–Lowell Partnership | Hazardous waste | Southeast Asians | University | 1995–2004 |

| Lower Price Hill Environmental Leadership Coalition | Industrial chemicals contamination | Indigent Whites | CBO | 1996–2005 |

| Environmental Justice Outreach In Northern Manhattan | Lead, air pollution | African Americans and Latinos | CBO | 1996–2005 |

| Community Health And Environmental Reawakening | Livestock, toxic waste, industrial pollution | African Americans | University | 1996–2008 |

| Health, Opportunities, Problem-Solving, and Empowerment | Reproductive health | Southeast Asian women | CBO | 1999–2003 |

| Silicon Valley Environmental Health and Justice Project | Hazardous waste | Latinos and Asians | CBO | 1999–2003 |

| Network For Responsible Stewardship | Hazardous wastes (military sites) | Alaska Natives | CBO | 1996–2000 |

| Uranium Education In The Navajo Nation | Uranium | Native Americans | University | 1996–2002 |

| Community Outreach For CTD Screening In High Risk Groups | Systemic lupus erythematosis | African Americans | University | 2000–2003 |

| Environmental Justice For St Lawrence Island, Alaska | Hazardous wastes | Alaska Natives | University | 2000–2004 |

| Environmental Impacts On Arab Americans In Metro Detroit | Inner-city environmental pollution | Indigent Arab Americans | CBO | 2000–2004 |

| Casa De Salud: A Model For Engaging Community | Asthma, lead | Latinos | CBO | 2000–2004 |

| Land Use, Environmental Justice, And Children's HealthCLEAN | Air pollution | Latinos | CBO | 2000–2008 |

| Casa A Campo: Pesticide Safety For Farmworkers' Families | Pesticides | Latinos | University | 2001–2005 |

| Community Assist Of Southern Arizona | Heavy metals | Latinos | CBO | 2001–2005 |

| Community Partnership For Asthma Prevention | Indoor and outdoor allergens | Inner-city children | University | 2001–2005 |

| Asthma And Lead Prevention In Chicago Public Housing | Indoor allergens, lead | African Americans and Puerto Ricans | CBO | 2001–2005 |

| Fish Consumption Risk Communication In Ethnic Milwaukee | Chemical contamination | Latinos and Hmong | University | 2001–2005 |

| Dietary Risks And Benefits In Alaskan Villages | Chemical contamination | Native Americans | CBO | 2001–2005 |

| South Valley Partners In Environmental Justice | Industrial and agricultural chemicals | Latinos and Native Americans | Health department | 2001–2005 |

| Contaminated Subsistence Fish: A Yakama Nation Response | Water contamination | Native Americans | CBO | 2001–2005 |

| Williamsburg Brooklyn Asthma and Environmental Consortium | Environmental and occupational asthma | Latinos | CBO | 2001–2005 |

| Bioaccumulative Toxics In Native American Shellfish | Chemical contaminants | Native Americans | CBO | 2001–2005 |

| South Bronx Environmental Justice Partnership | Air quality, toxic exposures | Indigent inner-city populations | University | 2001–2009 |

| Community Health Intervention With Yakima Agricultural Workers | Occupational hazards | Latino farmworkers | University | 2003–2007 |

| Community Collaborations For Farmworker Health And Safety | Occupational hazards | Farmworkers | University | 2003–2007 |

| Day Laborers United With The Community | Occupational hazards | Hispanic day laborers | Health department | 2003–2007 |

| Communities Organized Against Asthma And Lead (COAL) | Asthma triggers, lead | Latinos | University | 2003–2007 |

| Community Exposure To Perfluorooctanate | Perfluorooctanates contamination | The Appalachian community | University | 2003–2007 |

| Harlem Children's Zone Asthma Initiative | Asthma | African Americans | CBO | 2003–2007 |

| Dorchester Occupational Health Initiative | Occupational hazards | Vietnamese and Cape Verdeans | CBO | 2003–2007 |

| Work Environment Justice Partnership for Brazilian Immigrants | Solvents and other occupational hazards | Brazilian workers | University | 2003–2007 |

| Healthy Homes & Community for High Point Families | Multiple environmental exposures | Public-housing residents | Health department | 2003–2007 |

| Healthy Food, Healthy Schools and Healthy Communities | Obesity, diabetes | Urban, low-income Latinos | University | 2003–2007 |

| JUSTA: Justice and Health for Poultry Workers | Occupational hazards | Rural Latino poultry workers | University | 2004–2008 |

| Promoting Occupational Health Among Indigenous Farmworkers in Oregon | Occupational hazards | Indigenous farmworkers | CBO | 2004–2008 |

| Asian Girls for Environmental Health | Chemicals in beauty products | Asian women | CBO | 2004–2008 |

| Linking Breast Cancer Advocacy and Environmental Justice | Endocrine-disrupting compounds and other chemicals | African American and Latino women | CBO | 2004–2008 |

| Environmental Justice on Cheyenne River | Mercury, arsenic, other heavy metals | Native Americans | Health care provider | 2004–2008 |

| Strengthening Vulnerable Communities in Worcester | Toxic chemicals, violence | Low-income populations | University | 2004–2008 |

| Diné Network For Environmental Health (DiNEH) Project | Uranium, heavy metals | Native Americans | University | 2004–2008 |

| Partnership to Reduce Asthma and Obesity in Latino Schools | Indoor air quality, pests | Latino children | CBO | 2004–2008 |

| Environmental Health and Justice in Norton Sound, Alaska | Formerly used defense sites | Alaska Natives | CBO | 2005–2009 |

| Alton Park/Piney Woods Environmental Health and Justice | Chemical contamination | African Americans | University | 2005–2009 |

| Building Food Justice in East New York | Inequitable access to healthy food | African Americans and Latinos | University | 2005–2009 |

| South Valley Partners for Environmental Justice | Land-use decisions and urban sprawl | Latinos and low-income populations | CBO | 2005–2009 |

| Assessing and Controlling Occupational Health Risks in Somerville, MA | Occupational hazards | Immigrant workers | University | 2005–2009 |

| New York Restaurant Worker Health and Safety Project | Occupational hazards | Immigrant workers | CBO | 2005–2009 |

Note. NIEHS = National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences; NIOSH = National Institute for Occupation Safety and Health; EPA = Environmental Protection Agency; CBO = community-based organization; CTD = connective tissue disorder.

The structure of the program changed little over time, but adjustments were made to strengthen it. Initially the program's objective was to build bridges among the 3 required partners (community groups, health care professionals, and researchers), to build trust, to provide community residents with access to information, and to improve researchers' capacity to work in partnership with communities. In 1998, a second objective was added that encouraged partnerships to develop research strategies to identify, assess, and reduce environmental and occupational exposures and improve public health.7 In 2002, applicants were required to include an evaluation plan to measure public health impact and were encouraged to involve a social scientist in evaluation planning.

Demonstrating the success of large federal programs using measurable outcome-based metrics is essential to securing continued support.8,9 Here we examine the program's accomplishments in achieving its 2 broad objectives: (1) establish methods for linking members of a community who are directly affected by adverse environmental and occupational conditions with researchers and health care providers, and (2) enable partnerships to develop appropriate research strategies to address environmental and occupational health problems of concern in order to impact public health and health policy.7

METHODS

A team of researchers from the 3 funding agencies reviewed and synthesized data from grantees' project summaries developed for their annual meetings. We assumed that project teams would highlight key accomplishments in these reports. From 1994 to 2001 summaries were unstructured and usually 1 to 2 pages. There was no meeting report in 2002. From 2003 to 2007, when the agencies placed greater emphasis on evaluation and outcomes measurement,10 a more structured reporting format was used with sections for project aims, summary, health impacts, and policy impacts.

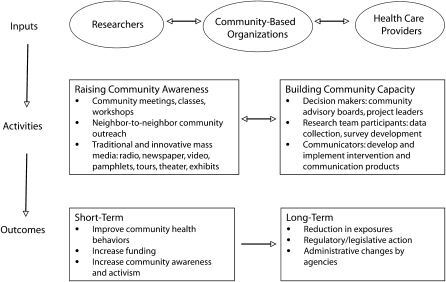

Because the program had no preexisting formal evaluation model, we developed one to guide this review process based on the program's 2 objectives (Figure 1). To review methods used to achieve these objectives, 4 team members (S. B., D. P., J. P., and L. O.) collected data from project summaries. After reviewing many activities across the 54 projects, we used an iterative process to classify the methods. Initially, all 4 reviewers exchanged and discussed examples from a small subset of projects to ensure a consistent approach to the extraction and coding process. Based on this initial review, we developed a list of output measures consistent with the project activities listed in Figure 1. Each member then reviewed and coded project summaries funded by or related to their agency's research portfolio.

FIGURE 1.

Program evaluation model for Partnerships for Communication.

To examine the program's success in impacting public health and health policy, a trained evaluator (R. S.) with no prior connection to the environmental justice program reviewed all of the summaries to identify project outcomes. We considered an outcome to have public health or policy impact when it involved actions by outside organizations and individuals to improve public health and health policy, that is, what others did as a result of the project, not what the project or its staff did. For example, if project staff spoke to a government oversight board, we did not count that as an outcome unless it appeared that they were invited by that board, rather than testifying without invitation in a public session.

RESULTS

We present the findings from our analysis of the project summaries according to the approach outlined in our evaluation model (Figure 1). First we summarize the major project activities that contributed to raising community awareness or building community capacity, then we describe the major outcomes or impacts on public health and health policy.

Raising Community Awareness

Given the program's central focus on communication, all of the projects reported various methods used to link communities and researchers by raising community awareness about environmental and occupational hazards and promoting preventive actions to improve health, such as using safer chemicals in the workplace or making home improvements to decrease asthma symptoms, such as improving the control of pests and dust. Reflecting the projects' commitment to community empowerment, projects also increased knowledge about how communities could take collective action to decrease exposures. For example, in at least 40 projects the community met with public officials, 31 projects organized public meetings or protests, and at least 20 conducted research to improve environmental regulations.

Almost all projects (53) conducted community meetings. Most (51) organized some form of class or workshop, ranging from brief educational presentations in community centers and religious institutions and technical information meetings in response to specific community complaints, to more-substantial community college courses and student internships. One project even created a 40-hour community course they called the Neighborhood Environmental College. Almost half (25) also targeted some training toward health care providers.

Nearly three fourths (35) of the projects organized train-the-trainer programs for community outreach workers. These “neighbor-to-neighbor” outreach programs were usually conducted by trained community members using a variety of innovative approaches, such as portable illustrated flip charts, photographs for digital storytelling, and interactive exercises.

Projects used a wide range of traditional and innovative mass media outlets, including radio, television, and newspapers; educational fact sheets and pamphlets; posters; videos and DVDs; audio cassettes; photo exhibits; community theater performances; and “treasures and toxics tours.” At least 41 projects developed printed materials; 34, electronic materials including videos, DVDs and Internet products; and 34 used radio, television, or newspapers.

Most commonly, the projects demonstrated the methods' effectiveness by quantifying outputs, such as the number of community members trained, the number of classes or radio shows created, or the number of educational pamphlets distributed. A few projects attempted to quantify evidence of increased community awareness by measuring changes in knowledge through pre- and posttraining tests. Summaries also included evidence of the projects' effectiveness by describing positive changes in individual behaviors and in community interest and activism. For example:

An evaluation of the Safe and Dignified Cleaning training program indicated that domestic workers participating in this Unidos project have gained leadership skills and self confidence, and have improved their health and well-being after implementing ergonomic changes and using less-toxic cleaning products. (From the Day Laborers United With the Community project; Table 1)

Over 200 girls and young women have successfully completed the leadership development and training program. Their efforts have resulted in two successful campaigns which shut down a Medical Waste Incinerator in Oakland and achieved 6 new policy changes that protects girls safety in public schools in Long Beach, California. (From the Health, Opportunities, Problem-Solving, and Empowerment project; Table 1)

Building Community Capacity

Community–researcher partnerships developed appropriate research strategies by building existing and newly emerging community leaders' capacity to become active partners in the projects' diverse research, outreach, and intervention activities. Project summaries described several methods for building leadership capacity, including engaging community leaders as decision makers, as members of the research team staff, and as key contributors to the design of effective intervention and dissemination products (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Community Roles in the Partnerships for Communication Projects: 1994–2007

| Community Role | Examples in Project Summaries (Project Name) |

| Decision makers | |

| Create networks of existing community organizations | Advisory boards in both project cities provided ongoing feedback and input from environmental justice organizations, breast cancer advocacy organizations, community residents, environmental health scientists, and health care and public health professionals. (Linking Breast Cancer Advocacy and Environmental Justice) |

| Create new community leadership and decision makers | The primary goal of the Bienestar Project was to develop strategies that will enable the community of Hispanic agricultural workers to effectively identify, characterize, and respond to the many occupational and environmental health risks. (Community Health Intervention With Yakima Agricultural Workers) |

| Research team members | |

| Provide culturally sensitive facilitators | We have conducted 8 focus groups in Spanish and indigenous languages. Project partners, especially the indigenous-language-speaking community educators, led this effort. (Promoting Occupational Health Among Indigenous Farmworkers in Oregon) |

| Improve survey design | Swinomish developed the methodology for the seafood diet interviews because data collection and analysis methods used in the previous studies may have led to inaccurate results based on inappropriate questions and survey methods not congruent with tribal knowledge transfer pathways. (Bioaccumulative Toxics In Native American Shellfish) |

| Improve sampling by better targeting hazards | As the Casa de Salud trainers taught Casa Leaders about the health effects of exposure to mercury through consumption of freshwater fish, the Casa Leaders told the trainers about the extensive and health-threatening ritualistic use of mercury in the community. (Casa De Salud: A Model For Engaging Community) |

| Improve cross-cultural outreach | One of the original justifications for working with our adolescent educators (fluently bilingual non-native English speakers) was their role as a source of information for and social connection between the English-speaking-only community and their non- or limited-English-speaking families. (Assessing and Controlling Occupational Health Risks in Somerville, MA) |

| Design appropriate interventions | A team of farmworkers and farm owners in a vegetable-producing region of New York addressed the problem of eye irritation caused by the very fine black soil in the region. Several different types of protective eyewear were selected by the workers and subsequently systematically tested in field trials. (Community Collaborations For Farmworker Health And Safety) |

| Design appropriate community training programs | Course facilitators and community members together prepared pilot course materials, incorporating ideas of the newly formed neighbors planning committee. Neighborhood staff and community members have been identified to facilitate other courses modeled on this pilot. (Alton Park/Piney Woods Environmental Health and Justice) |

| Developers of communication products | |

| Developing culturally appropriate communication messages | Tribal leaders believe that the health risk message is best delivered through an appeal for stewardship and protection of the salmon, and have expressed concern that focusing on personal behavior change would be viewed as forcing change on the victims of involuntary exposure. (Contaminated Subsistence Fish: A Yakama Nation Response) |

| Designing appropriate communication products | A group of 50 Asian girls were trained in the health and safety issues of personal cosmetic products. They decided that using a digital story telling format and some interactive exercises were the best way to educate their peers and they developed these intervention tools. (Asian Girls for Environmental Health) |

Community leadership's primarily role was as decision makers who prioritized health concerns, identified information gaps, and determined future research directions. Almost all (50) projects established some type of formal or informal community advisory board. In some, longstanding community-based environmental justice organizations with well-established capacity were the project leaders. In half (27), a community organization was the principal investigator and the researchers provided the organization with scientific and technical support (Table 1). In many others, researchers supported community leaders in catalyzing the creation of sustainable community organizations. In 2 projects this success was demonstrated when the community assumed primary responsibility, becoming the principal investigator.

The second major approach to increasing community leadership capacity was to incorporate community members into the projects' day-to-day data collection and information dissemination activities. Whether the community partner was a well-established organization or not, this development of skilled community research team members was a consistently positive accomplishment reported across the projects. Almost all (49) projects included community members as active (and frequently paid) members of the research team.

One popular approach was to develop youth leadership programs through summer and after-school programs and the creation of curriculum for schools and community colleges. Community youths were available, enthusiastic, and talented, and the community welcomed these programs as building sustainable community capacity. Over half (30) of the projects established youth leadership training programs, and 18 included components that allowed youths to reach out to other youths. Another common approach (35 projects) was to implement promotora, or lay health worker programs, providing training to a small group of paid community members who then collected data and sometimes implemented community outreach and training programs. These approaches were found to enhance many different components of the research (Table 2).

With communication a central objective of the program, an important method for improving researcher and community capacity was through their joint creation of innovative interventions and communication products. Projects emphasized the key role of community leaders in creating culturally appropriate communication messages and in choosing appropriate and effective information-dissemination formats (Table 2). For example, in a project targeting Latino indigenous farmworkers, community members suggested using dramatizations delivered by audiocassette, because many indigenous speakers are not familiar with their written language.

Impacts on Public Health and Health Policy

From project summaries we extracted 159 descriptions of outcomes that covered a broad range of actions by a variety of organizations and individuals. Prior to implementing the structured report format in 2003, which had sections on health and policy impacts, only 18 outcomes (11%) were reported. We subdivided the outcomes into long-term and short-term, based loosely on 2 criteria: long-term outcomes were more independent from project activities (perhaps indicating a stronger reaction by project stakeholders to the project) and more likely to have a more sustained positive impact on improving environmental justice (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Long- and Short-Term Project Outcomes From 54 Partnerships for Communication Projects: 1994–2007

| No. of Outcomesa | |

| Long-term | |

| Total | 75 |

| Reduction in community exposure to toxins | 6 |

| Government regulatory or legislative actions | |

| Actions to control current exposure | 18 |

| Actions to prevent new exposures | 9 (1) |

| Administrative activities by the government | |

| New and improved services | 10 (5) |

| Changes in practices | 24 (4) |

| Changes in government planning (land use, building public works) | 6 |

| Actions by nongovernmental organizations to decrease exposures | 2 |

| Short-term | |

| Total | 84 |

| Measurable improvements in community health outcomes | 4 |

| Input to external bodies not clearly associated with a measurable health or exposure outcome | 48 (2) |

| External agents sought funding to improve the environment as a result of project activities | 8 (2) |

| Increased awareness of environmental issues without measurable outcomes by: | |

| Media | 10 (1) |

| Colleges and universities | 5 (2) |

| Community members | 9 (1) |

Note. Outcomes were defined as actions taken by those external to the project to decrease exposures or improve health.

Numbers in parentheses indicate outcome numbers from reports prior to 2003, when a structured report format that included health and policy impacts was introduced.

We classified approximately half the outcomes as long-term. The first group (6 outcomes) included those outcomes that resulted in a direct reduction in exposure to a hazardous environmental toxin in a community. Examples included reductions in the use of toxic cleaning compounds in a large commercial cleaning worksite, reductions to airborne contaminants in auto body shops, and reductions in the use of toxins by computer manufacturers. Although not technically toxins, we also included the reduction in student access to unhealthy foods by school boards in Chicago, Illinois, and Los Angeles, California.

The second group was government regulatory or legislative actions (27 outcomes). Eighteen regulations or laws were supported in some way by projects. For example, with the help of children's health organizations, the South Bronx Environmental Justice Project saw their efforts with the New York City Council result in legislation to control diesel emissions from school bus idling. Similarly, another project supported the passage of a rule by the California Air Resources Board prohibiting plating operations that used hexavalent chromium from locating in residential or mixed-use neighborhoods. The other 9 outcomes concerned instances in which projects contributed to efforts to stop legislation, deny or change a government permit (e.g., landfill), or close down an organization classified as a public health threat (e.g., medical waste incinerator).

The third group of long-term outcomes involved administrative activities by government bodies (35 outcomes). Ten of these outcomes involved the provision of tangible infrastructure to a community (e.g., trash cans, pedestrian street safety enhancements, a sewer line). Some contributions were large, like an environmental justice center and a 24-hour complaint line. Others were small, such as the production of a pamphlet or warning signs. Nineteen outcomes in the third group involved government changes in practices such as enforcement of environmental regulations, public interface practices, staffing and training for government workers, and permits for organizations like pest control companies. In one case, partly because of efforts of the Communities Organized Against Asthma and Lead project, the Houston Mayor's Task Force on Air Quality worked with petrochemical facilities to reduce emissions of key pollutants. Six more outcomes involved changes in various types of government plans such as land use, abatement, clean-up priorities, environmental justice, and public works construction. Nine out of 10 of the pre-2003 outcomes were in this group.

The fourth group of long-term outcomes included cases in which nongovernmental organizations took actions to improve the well-being of citizens. Attorneys pursued compensation for injured workers. A manufacturer of blueberry harvesting rakes began marketing rakes that were less stressful on workers. An insurance company encouraged farm company clients to use employee training materials developed by the Together for Agriculture Safety project in Florida. Our analysis showed no clear differences in types of outcomes reported before and after the standardized reporting requirements, although most long-term outcomes prior to 2003 were in the category of government administrative changes (Table 3).

We organized the 84 short-term outcomes into 4 subgroups. The 8 pre-2003 outcomes were distributed across 3 of the 4 subgroups (Table 3). The first subgroup (3 outcomes) involved projects that achieved measurable positive health results. We considered these few cases of direct project action (rather than actions of others) to qualify as outcomes because they achieved the end outcome of health. For example, the Harlem Children's Zone Asthma Initiative achieved significant changes in asthma morbidity among enrolled children by providing education, social, environmental, medical, and legal supports.

Over half of the short-term outcomes (48; subgroup 2) involved collaborative actions taken by organizations working with environmental justice projects. In many projects, government or quasi-government agencies and legislative bodies requested data or asked for expert advice on issues. We differentiated such outcomes from major outcomes because it was not evident that the outcome resulted in a final action (e.g., a law) by outside bodies. Examples include:

The Dorchester Occupational Health Initiative, which advised the Alliance for a Healthy Tomorrow on “safer alternatives” legislation.

The Los Angeles Planning Department, which asked the Healthy Food, Healthy Schools, and Healthy Communities project for advice on food access issues.

The Environmental Justice on Cheyenne River project, which was asked for help in drafting legislation to create a Tribal Environmental Health Advisory Board.

Many project personnel were invited to serve on local or statewide advisory and regulatory boards such as the Boston Health Commission, the North Carolina Governor's Advisory Council on Hispanic/Latino Affairs, and the Houston Mayor's Taskforce on Air Quality. Staff advised government executives such as New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg and New York State Governor George Pataki on environmental issues. Almost every project described collaborations with other organizations for specific purposes. The Silicon Valley Health and Environmental Justice project worked with other organizations to develop policies on environmentally responsible electronics production and disposal. Most of the environmental justice projects in New York City were connected with a number of city and state activist organizations.

The next group of short-term outcomes involved action by organizations that were not project partners but were motivated by a project to secure funding for environmental work. For example, after the Community Health and Environmental Reawakening project identified the acute need for sewer work in a North Carolina community, the town government secured a $690 000 hardship loan from the EPA to build a new sewer line. As the result of working with another project, the City of Houston, Texas, secured a $750 000 grant for lead-exposure survey work. Other grants were not as large, and sometimes the amount of support was not reported, but these outcomes indicate the influence of projects on their collaborators.

The last group of short-term outcomes included reports of media coverage of project activities (at least 10 outcomes) and colleges and universities that added environmental justice courses or activities (at least 5 outcomes). It also included reports of groups of citizens who, as a result of a project, changed their awareness, interest, knowledge, and behaviors related to environmental issues. Although these individual changes may have had a substantial impact on well-being, we classified them in the final group of short-term outcomes because, for the most part, there was no discussed measurement of reported changes.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first evaluation of a major 13-year federal extramural funding program targeting environmental and occupational justice concerns and focusing on building communication and trust between communities and researchers. Our findings demonstrate the success of the program in achieving both of its objectives. Contributions of the funding program include developing successful methods for increasing community awareness and improving community capacity to create sustainable programs and to effectively advocate for health-promoting public policy and other actions to reduce exposures.

Our evaluation is consistent with findings by other researchers demonstrating the success of community-based participatory environmental justice research. Minkler et al.11 conducted in-depth case studies of 4 of the 54 projects and documented their success in building community capacity and changing public policy to control exposures. Cook's12 recent literature review of 33 Medline-indexed articles from 20 studies addressing disparities in environmental and occupational health demonstrated positive community-level action to improve health and also only included 4 of our 54 projects. Systematic literature reviews do not necessarily capture the full range of Partnerships for Communication projects, which prioritize science-based, education-outreach products targeting the local, rather than scientific, community. Our findings complement and expand these other findings by providing a review of the complete set of 54 projects funded within this program.

Although basing this evaluation on data drawn from project summary reports provided an opportunity to include all projects, this approach has limitations. All evidence reported was anecdotal and not part of a formal program evaluation; thus, a number of outcomes were likely not reported or detected and grantees may have been more motivated to report positive rather than negative outcomes. This is especially true prior to 2003, when no standardized report format was provided and fewer outcomes were reported. Additionally, all but 5 of the projects included at least 1 year of funding after the introduction of the structured reporting form (Table 1), so our evaluation may have underestimated the number of outcomes from the initial years. After 2002, funded projects required an evaluation plan, but there were no ongoing reports of evaluation results beyond the brief summaries. Finally, because only 1 evaluator completed the content analysis of outcomes, we could not examine the reliability of that coding process.

These limitations underscore the importance of federal agencies establishing systematic, ongoing evaluations, especially for large and innovative funding initiatives.8,9,13 Although it would increase program costs for federal funding agencies, rigorously designed prospective evaluations should engage stakeholders and use logic modeling or similar methods to map the intent of the program and to select output and outcome objectives. When possible, evaluations should include comparison groups of individuals, organizations, and even municipalities for which a similar program has not been implemented. Evaluation evidence should be collected both at baseline and follow-up from persons, documents, or observations. Careful analysis, clear statement of findings, and dissemination of findings to participants, funders, policymakers, and the public are all parts of appropriate program evaluation practice.14 Evaluations should also include methods and protocols to collect information appropriate for identifying and summarizing lessons learned, not just for collecting and documenting outcome data. Findings from systematic evaluations will also likely contribute to communities' and researchers' success in securing sustainable sources of funding for ongoing programs.

Much has been accomplished since the early 1990s, but minority and economically disadvantaged populations continue to bear a disproportionate share of environmental exposures and related illnesses.15,16 Concern for inequity among these groups is based not only on potentially higher levels of exposure to environmental hazards but also on synergistic effects of exposure to multiple contaminants and other stressors like poverty. In response, some environmental health researchers are blending social science with traditional environmental science methods.17 Interdisciplinary approaches and collaboration with sociologists, psychologists, and social epidemiologists are needed to examine the joint effects of social and environmental stressors. New developments in methods of analysis and multilevel approaches that can be combined with the successful community-based participatory research approaches developed through the Partnerships for Communication projects present opportunities to make advances in designing and evaluating interventions.18,19 These projects demonstrate the important role the community can play in appropriately designing and implementing these methods.20,21

When the Partnerships for Communication program was initiated in 1994, the expectation was that novel approaches for building trust and communication for community involvement in research would be developed. This approach is grounded in the presumption that in democratic societies health risks are best understood through the participation of all stakeholders, not just experts. Each stakeholder group brings a separate set of experiences, and the best and most efficient course for dealing with a health risk is determined through vigorous exchanges of information about risk among the stakeholders.22 Results of this evaluation support the importance of establishing good communication and set a baseline for future programs that bring together communities and universities to address environmental health issues. Looking to the future to meet the emerging and re-emerging issues, capacity building must continue to be supported to promote further mutual trust, understanding, and respect among all partners. Skills gained through such equitable partnerships may also contribute to communities' success in obtaining ongoing political and financial support to continue their work.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the community activists and leaders, the health care providers, and the researchers who created and implemented the 54 Environmental Justice Partnerships for Communication projects. We would also like to thank the federal leaders who supported the foundational work for this program as well as the staff who provided ongoing support during its implementation.

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was needed for this study because it involved secondary sources.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine Toward Environmental Justice: Research Education, and Health Policy Needs. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bullard RD. Dumping on Dixie: Race, Class and Environmental Quality. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shepard PM, Northridge ME, Prakash S, Stover G. Preface: Advancing environmental justice through community-based participatory research. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110(suppl 2):139–14011836141 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sexton K, Olden K, Johnson B. “Environmental Justice”: the central role of research in establishing a credible scientific foundation for informed decision making. Toxicol Ind Health. 1993;9(5):685–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson YB, Coulberson S, Phelps J. Overview of the EPA/NIEHS/ATSDR workshop—“Equity in Environmental Health: Research Issues and Needs.” Toxicol Ind Health. 1993;9(5):679–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Fallon LR, Dearry A. Community-based participatory research as a tool to advance environmental health sciences. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110(suppl 2):155–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Institute of Environmental Justice Environmental Justice and Community-Based Participatory Research, Program Description. Available at http://www.niehs.nih.gov/research/supported/programs/justice. Accessed April 25, 2009

- 8.Engel-Cox JA, Van Houten B, Phelps J, Shyanika RW. Conceptual model of comprehensive research metrics for improved human health and environment. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116(5):583–592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams VL, Eiseman E, Landree E, Adamson D. Demonstrating and communicating research impact: preparing NIOSH programs for external review. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corp; 2009. Available at: http://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG809. Accessed April 27, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Office of Management and Budget, US Government Program Assessment Rating Tool (PART). Available at: http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/part. Accessed April 26, 2009

- 11.Minkler M, Breckwich Vasquez V, Tajik M, Petersen D. Promoting environmental justice through community-based participatory reseach: the role of community and partnership capacity. Health Educ Behav. 2008;35:119–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cook WK. Integrating research and action: a systematic review of community-based participatory research to address health disparities in environmental and occupational health in the USA. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62:668–676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liebow E, Phelps J, Van Houten B, et al. Impacts of the NIEHS Extramural Asthma Research Program using available data. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117(7)1147–1154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Framework for program evaluation in public health. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48(RR-11):1–40 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Resnik DB, Roman G. Health, justice, and the environment. Bioethics. 2007;21(4):230–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brulle RJ, Pellow DN. Environmental justice: Human health and environmental inequalities. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:103–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gee GC, Payne-Sturges D. Environmental health disparities: A framework integrating psychosocial and environmental concepts. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112(17):1645–1653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merlo J, Chaix B, Yang M, Lynch J, Råstam L. A brief conceptual tutorial on multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: interpreting neighbourhood differences and the effect of neighbourhood characteristics on individual health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(12):1022–1028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diez Roux AV. Next steps in understanding the multilevel determinants of health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(11):957–959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vásquez VB, Minkler M, Shepard P. Promoting environmental health policy through community based participatory research: a case study from Harlem, New York. J Urban Health. 2006;83(1):101–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shulz A, Krieger J, Galea S. Addressing social determinants of health: community-based participatory approaches to research. Health Educ Behav. 2002;29:287–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelkin D. Communicating technological risk: the social construction of risk perception. Annu Rev Public Health. 1989;10:95–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]