Abstract

Prosurfactant protein C (proSP-C) is a 197-residue integral membrane protein, in which the C-terminal domain (CTC, positions 59–197) is localized in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) lumen and contains a Brichos domain (positions 94–197). Mature SP-C corresponds largely to the transmembrane (TM) region of proSP-C. CTC binds to SP-C, provided that it is in nonhelical conformation, and can prevent formation of intracellular amyloid-like inclusions of proSP-C that harbor mutations linked to interstitial lung disease (ILD). Herein it is shown that expression of proSP-C (1–58), that is, the N-terminal propeptide and the TM region, in HEK293 cells results in virtually no detectable protein, while coexpression of CTC in trans yields SDS-soluble monomeric proSP-C (1–58). Recombinant human (rh) CTC binds to cellulose-bound peptides derived from the nonpolar TM region, but not the polar cytosolic part, of proSP-C, and requires ≥5-residues for maximal binding. Binding of rhCTC to a nonhelical peptide derived from SP-C results in α-helix formation provided that it contains a long TM segment. Finally, rhCTC and rhCTC Brichos domain shows very similar substrate specificities, but rhCTCL188Q, a mutation linked to ILD is unable to bind all peptides analyzed. These data indicate that the Brichos domain of proSP-C is a chaperone that induces α-helix formation of an aggregation-prone TM region.

Keywords: Brichos domain, chaperone, protein misfolding, protein-peptide interactions, membrane protein, amyloid disease

Introduction

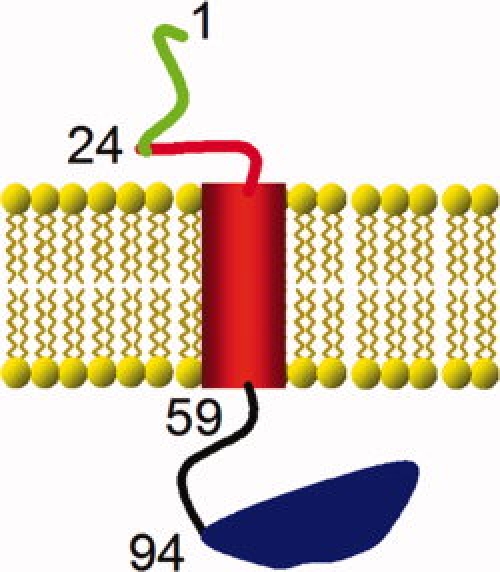

Lung surfactant protein C (SP-C) is a 35-residue lipopeptide with several unusual properties,1,2 see Figure 1 for a schematic representation of SP-C and its precursor, proSP-C. ProSP-C is a single pass integral membrane protein in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), wherein the SP-C part constitutes the transmembrane (TM) segment (see Fig. 1). However, in contrast to most TM ER proteins, SP-C, after proteolytic release from proSP-C, is secreted to the extracellular space embedded in phospholipid membranes.3 In the alveolar space SP-C, together with surfactant phospholipids and other surfactant-specific proteins, is necessary for creating a phospholipid film at the air-liquid interface, which ensures alveolar stability.4 SP-C is exclusively produced in the alveolar type II cell, is extremely hydrophobic due to the TM segment, which is composed only of Val, Ile or Leu (the “poly-Val” region), and lacks known homologous proteins.3,5

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the domains of proSP-C. Human proSP-C has 197 residues, wherein the part corresponding to the mature SP-C spans residues 24–58 (red). When inserted in the ER membrane, the N-terminal propart (residues 1–23, green) is localized in the cytosol and the CTC (Residues 59–197, black and blue) is localized in the ER lumen. The Brichos domain of CTC covers Residues 94–197 (blue). The domain corresponding to mature, membrane-inserted SP-C consists of the helical TM region (red cylinder) and a cytosolic N-terminal segment (red line). The first residue of each domain is identified by its sequence location in proSP-C.

SP-C avidly forms amyloid-like fibrils in vitro, and SP-C fibrils have been isolated from the alveolar spaces of patients with pulmonary alveolar proteinosis, where surfactant proteins accumulate in the alveoli.6 Recently, the connection between SP-C and amyloid formation gained further relevance by the finding that mutations in proSP-C identified in patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD)7 can result in proSP-C aggregation and formation of amyloid-like deposits in the human cell line HEK293.8 About 25 different proteins can turn into amyloid in association with disease.9 It is largely unknown what make these proteins particularly prone to convert from native structures to the β-sheet polymers found in amyloid-like fibrils. Likewise, how amyloid formation is modulated by specific and general chaperone systems is a complex question.10–13 These are important topics because amyloid-like fibrils and/or soluble protein oligomers that are thought to precede fibril formation are cell toxic and thereby can give rise to localized or systemic organ malfunction and disease.14

Recent data suggest that the C-terminal domain of proSP-C (CTC), which spans residues 59–197 and is localized in the ER lumen (see Fig. 1), prevents the poly-Val region of proSP-C from turning into amyloid during biosynthesis.8,15 Consequently, mutations in CTC can result in a loss of this anti-amyloid function, which may lead to cytotoxic protein aggregates and lung disease.8 Such a specialized anti-amyloid system has not been described previously. However, the substrate specificity and mechanism of action of CTC have not been investigated. In particular, it is not known whether CTC only prevents the proSP-C poly-Val region from aggregation, or if it also can induce folding into a TM α-helix.

CTC contains a Brichos domain, originally proposed from amino acid sequence comparisons of the Bri protein associated with familial British dementia, chondromodulin, and proSP-C.16 The Brichos domain is in most, but not all17 cases part of larger TM proproteins, localized in the ER lumen, and is about 100 residues in length (the CTC Brichos domain spans residues 94–197 according to sequence alignments). The Brichos domain was originally proposed to be involved in processing and maturation of the corresponding proproteins.16 Previous studies showed that recombinant human (rh) CTC binds unfolded, but not α-helical SP-C, and can also associate with phospholipid membranes.15,18 These properties are in line with an anti-amyloid function toward membrane bound proSP-C in the ER.8,15 Most of the proSP-C mutations associated with ILD and intracellular protein aggregation, for example, L188Q are localized in the Brichos domain.3

In this report, we tested the hypothesis that CTC works as a chaperone toward the TM segment of proSP-C by investigating its ability to affect the stability and folding of proSP-C(1–58) in human embryonic kidney (HEK)293 cells, and the secondary structure of synthetic peptides in solution. We also determined the substrate specificities of rhCTC, mutant rhCTCL188Q, and the proSP-C Brichos domain (rhCTCBrichos) using cellulose-bound peptides covering the entire sequence of SP-C. The results indicate that CTC, via its Brichos domain, can prevent aggregation and induce folding of the TM segment of proSP-C.

Results

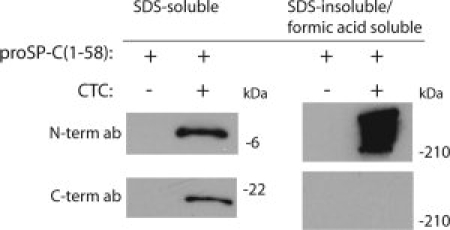

CTC affects stability and folding of proSP-C(1–58) in HEK293 cells

Expression levels and solubility properties were analyzed for proSP-C(1–58) expressed in HEK293 cells alone, or coexpressed with CTC (proSP-C(59–197)). When expressed alone proSP-C(1–58) could neither be detected in the SDS cell lysate, nor in the SDS insoluble/formic acid soluble fraction (see Fig. 2). Analysis by RT-PCR confirmed mRNA expression of the proSP-C(1–58) (data not shown). Treatment of the cells with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 resulted in detection of small amounts of proSP-C(1–58) in the SDS-soluble phase (data not shown), suggesting that the protein is synthesized, but rapidly degraded. Coexpression of CTC, in trans, stablilizes the proSP-C(1–58) protein and rescues it from degradation, and it can be found in the SDS-soluble cell lysate (see Fig. 2). Coexpression of proSP-C(1–58) and CTC also results in a pool of aggregated, SDS insoluble/formic acid soluble proSP-C(1–58). No CTC protein was detected in this fraction, which indicates that aggregated proSP-C(1–58) is not bound to CTC (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

CTC stabilizes proSP-C(1-58). Western blots of lysates from HEK293 cells expressing proSP-C(1–58) alone or in combination with a signal peptide-proSP-C(59–197) construct. SDS-soluble, and SDS-insoluble/formic acid soluble phases of cell lysates were probed with antibodies against the N-terminal and the C-terminal part of proSP-C, for detection of proSP-C(1–58) and CTC, respectively.

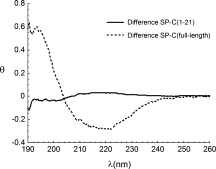

Secondary structure effects of rhCTC-peptide interactions

CD spectroscopy of synthetic SP-C(1–21) dissolved in SDS micelles shows a typical β-strand structure (data not shown). The same analysis in the presence of rhCTC shows no change in secondary structure (see Fig. 3). This differs from the effect of rhCTC interaction with β-strand full-length synthetic SP-C, which results in increased α-helical content (see Fig. 3).15

Figure 3.

Effects of rhCTC binding on secondary structure depend on length of poly-Val region. Difference spectra obtained by subtraction of the experimentally measured and calculated spectra for rhCTC plus SP-C(1–21) (solid line) and rhCTC plus full-length β-strand SP-C (dotted line). The mean molar residual ellipticity (θ) is expressed as kdeg × cm2/dmol.

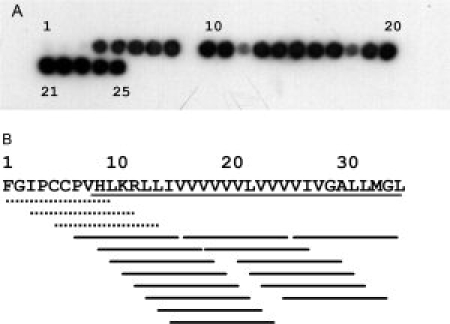

Binding of rhCTC to peptide fragments derived from SP-C

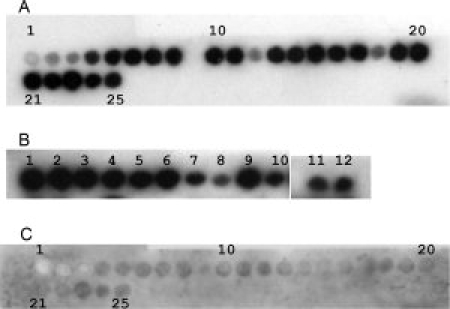

Ten-residue peptides with overlapping sequences corresponding to the entire SP-C amino acid sequence (proSP-C positions 24–58) bound to cellulose membranes were probed for binding to rhCTC. Figure 4 shows that binding motifs are found in the region that contains hydrophobic residues, that is, peptides derived from the “poly-Val” region of SP-C. Replacement of poly-Val motifs with poly-Leu results in no change in binding, compare spot pairs 7/8, 10/11, and 16/17, respectively, in Figure 4(A). In contrast, replacement of poly-Val with poly-Ala results in abolished binding, compare spots 7/9, 10/12, and 16/18, respectively, in Figure 4(A).

Figure 4.

RhCTC binds to the TM region of (pro)SP-C. (A) binding of rhCTC to spots containing 10-residue fragments derived from SP-C (red part in Fig. 1). The peptide spots 1 to 25 cover the SP-C sequence in an N- to C-terminal direction. Spot 7 contains the KRLLIVVVVV segment in SP-C, whereas Spots 8 and 9 contain Leu- (KRLLLLLLLL) or Ala-substituted (KRAAAAAAAA) versions thereof, respectively. In the same manner spots 10–12 contain RLLIVVVVVV (positions 12–21 in SP-C), RLLLLLLLLL, and RAAAAAAAAA, respectively, and spots 16–18 contain VVVVVLVVVV (positions 17–26 in SP-C), LLLLLLLLLL, and AAAAAAAAAA, respectively. Spots 21 and 23 contain the same peptide (LVVVVIVGAL). (B) summary of rhCTC binding along the SP-C sequence. Dotted lines mark peptides to which rhCTC does not bind, while the solid lines represent peptides to which rhCTC binds. The underlined part of the SP-C sequence corresponds to the TM region. The numbering 1–35 refer to the mature SP-C peptide, the corresponding residues in proSP-C are 24–58 (see Fig. 1).

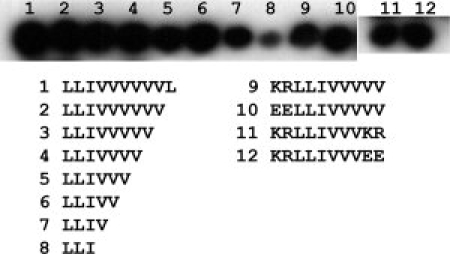

By truncating the LLIVVVVVVL peptide stepwise by one residue from the C-terminus, it was found that 5 consecutive hydrophobic residues confer binding which is similar to that seen for peptides containing 6–10 residues (Fig. 5, spots 1–8). Four consecutive hydrophobic residues still results in detectable binding, but apparently lower than for the 5-residue peptide, while a cellulose-bound peptide containing three consecutive hydrophobic residues results in low rhCTC binding (see Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Effects of peptide length and charge on rhCTC binding. Binding of rhCTC to spots containing LLIVVVVVVL (positions 13–22 in SP-C) and truncated versions thereof (Spots 1–8), and the peptide KRLLIVVVVV (positions 11–20 in SP-C) and variants thereof with different charge distributions (spots 9–12).

SP-C contains two juxtaposed positively charged residues localized in the N-terminal part of the TM helix [Fig. 4(B)]. Replacing these residues with negatively charged residues does not affect binding of rhCTC (Fig. 5, Spots 9 and 10). Peptides with six centrally located hydrophobic residues flanked by positively or negatively charged residues also bind to rhCTC (Fig. 5, Spots 11 and 12).

Binding specificities of proSP-C Brichos domain and mutant CTC

The same peptide spot membranes as used for analysis of rhCTC substrate specificity were probed with rhCTCBrichos (residues 94–197 of proSP-C, Fig. 1), which showed a binding profile very similar to that of rhCTC (Fig. 6(A,B)]. In contrast, rhCTCL188Q did not bind to any fragment of SP-C [Fig. 6(C)].

Figure 6.

The Brichos domain recapitulates the CTC binding properties while the mutation L188Q destroys binding. Binding of rhCTCBrichos to the same membranes as used in Figure 4A (A) and in Figure 5 (B). (C) shows the binding pattern of rhCTCL188Q to the membrane containing peptides derived from SP-C (same membrane as in A).

Discussion

Functional properties of CTC

Analysis of proSP-C(1–58) expressed with or without CTC in trans in HEK293 cells, using a bicistronic vector, indicate that CTC works as a chaperone for the TM region of (pro)SP-C (see Fig. 2). In the absence of CTC, the levels of proSP-C(1–58) are barely detectable and the protein is being degraded by the proteasome, as judged by an increase by treatment of the cells with a proteasome inhibitor. With CTC present in the ER lumen, however, proSP-C(1–58) levels are clearly increased and an SDS-soluble monomeric form is found (see Fig. 2). The influence of CTC seems to be specific, because coexpression of the mutant form CTCL188Q does not influence the levels of proSP-C(1–58) (J. Presto et al, unpublished). Previously a complex between full-length proSP-CL188Q and CTC expressed in HEK293 cells was detected, but the binding site in proSP-C was not established.8 The present data strongly support that interactions take place between the proSP-C TM segment and CTC. Moreover, α-helical SP-C is readily dissolved by SDS, in contrast to aggregated, β-sheet SP-C. These results therefore also suggest that CTC promotes formation of α-helical, proSP-C(1–58). This is supported by the finding that mixing nonhelical SP-C and rhCTC results in a difference CD spectrum indicative of increased α-helical content (see Fig. 3). In contrast, mixing SP-C(1–21) and rhCTC results in no change in secondary structure (Fig. 3) and therefore the increase in helical content for rhCTC/SP-C likely occurs in SP-C rather than in rhCTC. The poly-Val region in SP-C(1–21), (9 residues) is not much longer than the minimal length for peptide binding to rhCTC (5–7 residues, see later). A likely explanation for the different effects of rhCTC binding to full-length SP-C versus SP-C(1–21) is that helix formation occurs in parts of SP-C that are not in contact with CTC. Taken together the data in Figures 2 and 3 indicate that CTC binds nonhelical TM regions of proSP-C and promotes folding into α-helical conformation.

Expression of proSP-C(1–58) alone results in no detectable aggregated protein (see Fig. 2), which suggests that it is degraded efficiently enough to prevent aggregation. These results agree well with the finding that in the absence of specific chaperones, TM amino acid permeases undergo precocious ER associated degradation, indicating that folding and degradation are coupled during membrane protein biogenesis.19 It is possible that membrane-inserted proSP-C(1–58) is not fully stable because its C-terminal end coincides with the end of the TM helix. This may explain the observation of aggregated proSP-C(1–58), along with the monomeric protein, after coexpression with CTC (Fig. 2). It is presently under investigation whether C-terminally elongated constructs, for example, proSP-C(1–73), are more stable.

It can be noted that (pro)SP-C apparently has intrinsic features that stabilize the TM helix, once it has formed. Removal of the palmitoyl groups linked to Cys5 and Cys6 of SP-C (see Fig. 4) results in increased conversion from the soluble α-helical state to β-sheet fibrils.20,21 Likewise, the 12-residue segment preceding SP-C locks the metastable polyvaline part in α-helical conformation.22 Both the palmitoyl groups and the N-terminal propeptide part affects helical stability in a pH dependent manner, suggesting that their influences vary along the secretory pathway, where pH is lowered from the ER to the lamellar bodies.20,23

Substrate binding is localized to the CTC Brichos domain

CTC binds to any part of the TM region of (pro)SP-C, as shown by binding to 10-residue peptides immobilized on cellulose filters, and the same property is shown by the Brichos domain alone (Figs. 4 and 6). By reducing the peptide lengths, it appears that rhCTC/rhCTCBrichos has a binding pocket that covers at least five residues (Figs. 5 and 6). Using peptides in solution, it was previously shown that the peptide KKVVVVVVVKK forms a complex with rhCTC, but KKVVVVVKK does not.15 The reasons for the discrepancy between peptide length requirement for binding to rhCTC using cellulose-bound and soluble peptides can not be resolved at the present, but the combined data allow us to conclude that the Brichos domain of proSP-C binds to peptide segments of at least 5–7 residues.

RhCTC and rhCTCBrichos has the same substrate specificity, while rhCTCL188Q shows abolished substrate binding (see Fig. 6 and Ref.15). Moreover, proSP-CL188Q (mutation localized within the Brichos domain) forms amyloid-like inclusions in HEK293 cells, while proSP-CI73T (mutation localized outside the Brichos domain) does not.8 These data suggest that the Brichos domain of proSP-C is a structural and functional unit, offering a possible explanation as to why phenotypic effects of mutations in proSP-C seem to differ depending on whether they are localized within or outside the Brichos domain.3

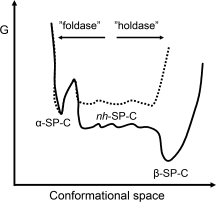

Implications for CTCBrichos mechanism of action

The α-helix of SP-C, which corresponds to the TM helix of proSP-C, is in a metastable state relative to nonhelical conformations24 (Fig. 7, solid line). A high barrier for formation of a poly-Val α-helix is related to the fact that it requires β-branched side-chains to adopt fixed positions. Binding of CTCBrichos to the nonhelical TM region may result in an elevated energy state for the poly-Val segment, via entropy loss, from which formation of a helix is energetically favorable (Fig. 7, dotted line). It has been shown that nucleation of TM helix formation can occur already in the ribosome, possibly mediated by hydrophobic interactions between the TM segment analyzed and ribosome components.25 However, such a mechanism likely does not apply to proSP-C, as a poly-Val segment does not form a compact, helical conformation neither in the ribosome, nor in the ER translocon.26 Independent of helix formation, binding of CTCBrichos to a nonhelical TM region of proSP-C is expected to prevent its formation of β-sheet aggregates. The proSP-C Brichos domain thus may work both as a “holdase” and as a “foldase” (see Fig. 7), analogous to the actions of chaperones like members of the Hsp70 family.27

Figure 7.

Model for the chaperone activity of CTCBrichos. The solid line represents the free energy profile for α-helical, non-helical (nh), and β-sheet SP-C, deduced from NMR hydrogen/deuterium exchange studies.24 Whether nh-SP-C has a lower energy than α-SP-C is not fully resolved.24 In the absence of CTCBrichos the poly-Val region of SP-C (the TM region of proSP-C) favors formation of β-sheet aggregates over α-helix. The proposed effect of CTCBrichos binding to the nonhelical poly-Val part (dotted line) is twofold; it favors helix formation (“foldase”) by reducing the entropic cost associated herewith, and it prevents peptide-peptide interactions required for β-sheet aggregation (“holdase”).

The proSP-C Brichos domain may specifically promote helix formation/prevent aggregation of the proSP-C poly-Val TM segment, which has an unusually high β-strand propensity.28 Membrane-integrated chaperones that work specifically on TM regions and prevent their aggregation have been described.29,30 A suggested mechanism of action of these chaperones is to bind polar parts of certain TM helices, thereby preventing them from aggregation in the nonpolar membrane interior before they find their correct TM segment partners.29 The proSP-C Brichos domain differs from these chaperones by acting upstream of TM helix formation and by not being integrated into the membrane.

In Hsp70 chaperones, efficient substrate release is accomplished by conformational changes elicited by nucleotide binding and release cycles.27 In the postulated CTCBrichos mechanism of action (see Fig. 7) substrate binding and α-helix formation are coupled, which implies that the initially bound peptide region can be translocated out of the binding pocket as the TM segment folds and shortens. Notably, the strictly conserved polypeptide segment (HMSQKHTE) that follows directly C-terminal of the proSP-C TM part is composed largely of polar and charged residues to which CTCBrichos apparently does not bind (Figs. 4 and 6, Spots 1–3).

In conclusion, the present work suggests that the proSP-C Brichos domain is the first described chaperone that targets an unfolded TM segment.

Materials and Methods

Expression and isolation of rhCTCBrichos, rhCTC and rhCTCL188Q

The rhCTC and rhCTCL188Q constructs were made as described in,15 the rhCTCBrichos construct was amplified from the rhCTC construct and the primers (DNA technology AIS, Aarhus, Denmark): 5′- GGTGCCATGGCTTTCTCCATCGGCTCCACT-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-CTCTAGAGGATCCGGATCCCTAGATGTAGTAGAGCGGCACCTCC-3′ (reverse primer); the underlined sequences are BamH1 and Nco1 cleavages sites, respectively. The amplified DNA fragment was digested with BamH1 and Nco1 and ligated into the expression vector pET-32c (Novagen, Madison, WI). This vector contains the coding regions for thioredoxin, hexahistidine and S-tags upstream of the insertion site.

For the expression of rhCTCBrichos, transformed E. coli, strain Origami (DE3) pLysS (Novagen, Madison, WI) were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin for 16 h with constant stirring. The temperature was lowered to 25°C and expression was induced at an OD600 = 1.1 by the addition of IPTG to 0.5 mM, and the bacteria were grown for another 4 h. The cells were then harvested by centrifugation at 6000g for 20 min, incubated with lysozyme and DNase in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 2 mM MgCl2 and further loaded onto a Ni-NTA agarose column. The column was washed with 100 mL of 20 mM Tris, pH 8, and then with 20 mL of 20 mM Tris, pH 8, containing 20 mM imidazole. The target protein was then eluted with 150 mM imidazole in 20 mM Tris, pH 8. The eluted protein was dialyzed against 20 mM Tris, pH 8, where after thioredoxin and His tags were removed by cleavage with thrombin at an enzyme/substrate weight ratio of 0.002 for 3 h at 8°C. After this imidazole was added to a concentration of 15 mM and the solution was reapplied to a Ni-NTA agarose column to remove the released thioredoxin-His tag. RhCTC and rhCTCL188Q were expressed and purified as described earlier.15 In brief, the protein was expressed as a fusion protein with thioredoxin/His6/S-tag in E. coli. The protein was purified using immobilized metal affinity and ion exchange chromatography. Thrombin was used to remove the thioredoxin-tag and His6-tag. The protein purity was checked with SDS-PAGE and nondenaturing PAGE.

Cloning, transfection and HEK293 clones

Human proSP-C cDNA (GenBank accession no. NM_003018) coding for amino acid residues 1–58 or 59–197 (CTC) of proSP-C, were cloned into the pBudCE4.1 vector (Invitrogen), which contains two multiple cloning sites (MCS), designed for simultaneous expression of two proteins. This system eliminates variable expression levels of the two proteins due to differences in gene copy number. The pBudCE4.1 vector uses the cytomegalovirus immediate-early (CMV) and human elongation factor 1α (EF-1α) promoters. These promoters give high-level and similar expression levels of recombinant proteins in HEK293 cells.31 The coding sequences include a preferred Kozak sequence (GCC ACC) upstream of the start codon. ProSP-C(1–58) was cloned into the MCS with the CMV promoter (by use of restriction enzymes BamHI and XbaI) and proSP-C(59–197) was cloned into the MCS with the EF-1α promoter (by use of restriction enzymes XhoI and NotI). Upstream of the proSP-C(59–197) sequence, the signal peptide of proSP-B (Residues 1–23) was inserted to ensure ER localization of the CTC protein. One construct with only proSP-C(1–58) and one with both proSP-C(1–58) and proSP-C(59–197) were transfected into HEK293 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Stable clones were selected by using 0.4 mg/mL Zeocin (Invitrogen) and were grown in DMEM containing L-glutamine, 10% fetal calf serum, 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (SVA, Uppsala, Sweden). Several clones expressing proSP-C(1–58) alone and in combination with CTC were selected and maintained in DMEM as earlier, with the addition of 0.2 mg/mL Zeocin.

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting

HEK293 cell pellets were washed in PBS and solubilized in 1% SDS, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM PEFA-block, by sonication for 5 min. Two millimolar MgCl2 and 15 U of benzonase (Merck) was added to the samples, which were then incubated at 20°C for 20 min with shaking, followed by centrifugation at 16,000g at 4°C for 45 min. To an aliquot of the supernatants, SDS-loading buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol was added. The pellets were dissolved in 1% SDS in formic acid, dried and redissolved in 11% glycerol, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and SDS-loading buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol was added. The samples were then boiled for 4 min before separation on 10–15% Tris-glycine gels and electroblotted to PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad miniProtean). The membranes were treated with 0.5% glutaraldehyde, washed in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 0.15M NaCl (TBS) 2 × 10 min followed by incubation in blocking buffer containing 7% nonfat milk in TBS with 0.1% Tween20 for 1 h. Then the membranes were incubated with polyclonal antibodies directed against the N-terminal or the C-terminal domain, respectively, of proSP-C,8 both diluted 1:10,000 in blocking buffer for 1 h. The secondary antibody, anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated antibody (GE Healthcare), was diluted 1:5000 in blocking buffer. The filters were developed in an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) system (Millipore) and exposed to Fuji film.

Analysis of rhCTCBrichos, rhCTC and rhCTCL188Q binding to peptide spots on cellulose membranes

SPOT membranes,32 containing peptides described in the Results section were purchased from Sigma Genosys (Cambridge, England). The membranes were soaked in methanol for 5 min and then washed 3 × 30 min with T-TBS (50 mM Tris, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, pH 8, containing 0.05% Tween) followed by incubation with 1 μg/mL rhCTCBrichos, rhCTC or rhCTCL188Q in T-TBS for 1 h at 22°C. The membranes were then blocked with 2% BSA in TBS for 1 h. After washing with T-TBS 4 × 1 h, the membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated S-protein (Novagen, Madison, WI) diluted 1:5000 in T-TBS containing 2% BSA. The membranes were then washed again with T-TBS 4 × 1 h and binding was visualized by ECL according to the manufacter's instructions.

Circular dichroism (CD) analysis

CD spectra in the far-UV region (190–260 nm) were recorded at 22°C with a Jasco J-810-150S spectropolarimeter (Jasco, Tokyo, Japan) using a bandwidth of 1 nm and a response time of 2 s, and 10 data points/nm were collected. Each spectrum shown is the average of three consecutive recordings. Spectra were recorded of: rhCTC (10 μM) in 2% (w/v) SDS micelles in 20 mM NaH2PO4, 5 mM NaCl; synthetic SP-C(1–21) (10 μM) or synthetic full-length SP-C (10 μM) in 2% (w/v) SDS micelles in 20 mM NaH2PO4, 5 mM NaCl; or combinations of rhCTC and SP-C peptides in 2% (w/v) SDS micelles. For incorporation of peptides into SDS micelles, SDS was dissolved in MeOH and synthetic full-length SP-C or SP-C(1–21) (dissolved in formic acid) was added, and the solutions were incubated at 37°C until the solvents were evaporated. SDS micelles were then prepared by resuspension in 20 mM NaH2PO4, 5 mM NaCl. For analysis of rhCTC in the presence of SDS micelles, the micelles were prepared first, and then the rhCTC was added.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. Tim Weaver for helpful discussion and for gifts of proSP-C vectors.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- HEK

human embryonic kidney

- ILD

interstitial lung disease

- MCS

multiple cloning sites

- nh

nonhelical

- rhCTCBrichos

recombinant human Brichos domain, residues 94–197 of proSP-C

- rhCTC

recombinant human C-terminal domain, residues 59–197 of proSP-C

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulphate

- SP-C

surfactant protein C

- TM

transmembrane

References

- 1.Brown NJ, Johansson J, Barron AE. Biomimicry of surfactant protein C. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:1409–1417. doi: 10.1021/ar800058t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitsett JA, Weaver TE. Hydrophobic surfactant proteins in lung function and disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:2141–2148. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beers MF, Mulugeta S. Surfactant protein C biosynthesis and its emerging role in conformational lung disease. Annu Rev Physiol. 2005;67:663–696. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.040403.101937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almlén A, Stichtenoth G, Linderholm B, Haegerstrand-Björkman M, Robertson B, Johansson J, Curstedt T. Surfactant proteins B and C are both necessary for alveolar stability at end expiration in premature rabbits with respiratory distress syndrome. J Appl Phys. 2008;104:1101–1108. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00865.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johansson J, Weaver TE, Tjernberg LO. Proteolytic generation and aggregation of peptides from transmembrane regions: lung surfactant protein C and amyloid β-peptide. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:326–335. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3274-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gustafsson M, Thyberg J, Naslund J, Eliasson E, Johansson J. Amyloid fibril formation by pulmonary surfactant protein C. FEBS Lett. 1999;464:138–142. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01692-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamvas A, Cole FS, Nogee LM. Genetic disorders of surfactant proteins. Neonatology. 2007;91:311–317. doi: 10.1159/000101347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nerelius C, Martin E, Peng S, Gustafsson M, Nordling K, Weaver TE, Johansson J. Mutations linked to interstitial lung disease can abrogate anti-amyloid function of prosurfactant protein C. Biochem J. 2008;41:201–209. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Westermark P. Aspects on human amyloid forms and their fibril polypeptides. FEBS J. 2005;272:5942–5949. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.05024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ecroyd H, Carver JA. Crystallin proteins and amyloid fibrils. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:62–81. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8327-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muchowski PJ. Protein misfolding, amyloid formation, and neurodegeneration. A critical role for molecular chaperones? Neuron. 2002;35:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00761-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muchowski PJ, Wacker JL. Modulation of neurodegeneration by molecular chaperones. Nat Rev. 2005;6:11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrn1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shorter J, Lindquist S. Hsp104, Hsp70 and Hsp40 interplay regulates formation, growth an elimination of Sup35 prions. EMBO J. 2008;27:2712–2724. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ecroyd H, Carver JA. Unraveling the mysteries of protein folding and misfolding. IUBMB Life. 2008;60:769–774. doi: 10.1002/iub.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johansson H, Nordling K, Weaver TE, Johansson J. The Brichos domain-containing C-terminal part of pro-surfactant protein C binds to an unfolded poly-val transmembrane segment. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:21032–21039. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603001200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanchez-Pulido L, Devos D, Valencia A. BRICHOS: a conserved domain in proteins associated with dementia, respiratory distress and cancer. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:329–332. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Westley BR, Griffin SM, May FE. Interaction between TFF1, a gastric tumor suppressor trefoil protein, and TFIZ1, a brichos domain-containing protein with homology to SP-C. Biochemistry. 2005;44:7967–7975. doi: 10.1021/bi047287n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casals C, Johansson H, Saenz A, Gustafsson M, Alfonso C, Nordling K, Johansson J. C-terminal, endoplasmic reticulum-lumenal domain of prosurfactant protein C - structural features and membrane interactions. FEBS J. 2008;275:536–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kota J, Gilstring F, Ljungdahl PO. Membrane chaperone Shr3 assists in folding amino acid permeases preventing precocious ERAD. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:616–628. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200612100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dluhy RA, Shanmukh S, Leapard JB, Krüger P, Baatz JE. Deacylated pulmonary surfactant protein SP-C transforms from α-helical to amyloid fibril structure via a pH-dependent mechanism: an infrared structural investigation. Biophys J. 2003;85:2417–2429. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(03)74665-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gustafsson M, Griffiths WJ, Furusjö E, Johansson J. The palmitoyl groups of lung surfactant protein C reduce unfolding into a fibrillogenic intermediate. J Mol Biol. 2001;310:937–950. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li J, Hosia W, Hamvas A, Thyberg J, Jornvall H, Weaver TE, Johansson J. The N-terminal propeptide of lung surfactant protein C is necessary for biosynthesis and prevents unfolding of a metastable α-helix. J Mol Biol. 2004;338:857–862. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J, Liepinsh E, Almlén A, Thyberg J, Curstedt T, Jörnvall H, Johansson J. Structure and influence on stability and activity of the N-terminal propeptide part of lung surfactant protein C. FEBS J. 2006;273:926–935. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szyperski T, Vandenbussche G, Curstedt T, Ruysschaert JM, Wuthrich K, Johansson J. Pulmonary surfactant-associated polypeptide C in a mixed organic solvent transforms from a monomeric α-helical state into insoluble β-sheet aggregates. Protein Sci. 1998;7:2533–2540. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560071206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woolhead CA, McCormick PJ, Johnson AE. Nascent membrane and secretory proteins differ in FRET-detected folding far inside the ribosome and in their exposure to ribosomal proteins. Cell. 2004;116:725–736. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mingarro I, Nilsson I, Whitley P, von Heijne G. Different conformations of nascent polypeptides during translocation across the ER membrane. BMC Cell Biol. 2000;1:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mayer MP, Bukau B. Hsp70 chaperones: cellular functions and molecular mechanism. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:670–684. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4464-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kallberg Y, Gustafsson M, Persson B, Thyberg J, Johansson J. Prediction of amyloid fibril-forming proteins. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12945–12950. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010402200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kota J, Ljungdahl PO. Specialized membrane-localized chaperones prevent aggregation of polytopic proteins in the ER. J Cell Biol. 2004;168:79–88. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200408106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schamel WWA, Kuppig S, Becker B, Gimborn K, Hauri HP, Reth M. A high-molecular-weight complex of membrane proteins BAP29/BAP31 is involved in the retention of membrane-bound IgD in the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9861–9866. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1633363100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Running Deer J, Allison DS. High-level expression of proteins in mammalian cells using transcription regulatory sequences from the Chinese hamster EF-1α gene. Biotechnol Prog. 2004;20:880–889. doi: 10.1021/bp034383r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frank R. The SPOT-synthesis technique. Synthetic peptide arrays on membranes supports-principles and applications. J Immunol Methods. 2002;267:13–26. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(02)00137-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]