Abstract

The expression of mammalian membrane proteins in laboratory cell lines allows their biological functions to be characterized and carefully dissected. However, it is often difficult to design and generate effective antibodies for membrane proteins in the desired studies. As a result, expressed membrane proteins cannot be detected or characterized via common biochemical approaches such as western blotting, immunoprecipitation, or immunohistochemical analysis, and their cellular behaviors cannot be sufficiently investigated. To circumvent such roadblocks, we designed and generated two sets of expression modules that consist of sequences encoding for three essential components: (1) a signal peptide from human receptor for advanced glycation end products that targets the intended protein to the endoplasmic reticulum for cell surface expression; (2) an antigenic epitope tag that elicits specific antibody recognition; and (3) a series of restriction sites that facilitate subcloning of the target membrane protein. The modules were designed with the flexibility to change the epitope tag to suit the specific tagging needs. The modules were subcloned into expression vectors, and were successfully tested with both Type I and Type III human membrane proteins: the receptor for advanced glycation end products, the Toll-like receptor 4, and the angiotensin II receptor 1. These expressed membrane proteins are readily detected by western blotting, and are immunoprecipitated by antibodies to their relative epitope tags. Immunohistochemical and biochemical analyses also show that the expressed proteins are located at cell surface, and maintain their modifications and biological functions. Thus, the designed modules serve as an effective tool that facilitates biochemical studies of membrane proteins.

Keywords: membrane protein expression module, epitope tag, RAGE signal peptide, multicloning sites, western blotting, immunoprecipitation, immunohistochemistry

Introduction

Expression of a mammalian protein in laboratory cell lines is the most common approach used to study its biological functions including cellular localization, trafficking, translocation, and interaction with other cellular factors.1–4 This approach can also serve to produce recombinant proteins on a laboratory scale for structural studies, or on an industrial scale for therapeutic purposes.5–7 Although overexpression of mammalian genes in bacterial cells is often used for large-scale protein productions, in many cases, the expressed mammalian proteins, especially membrane proteins, are either misfolded, or function incorrectly, owing to the lack of necessary posttranslational modifications. Expression in eukaryotic model systems such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae or insect cell lines may accommodate posttranslational modifications to a certain degree, but these systems do not completely mimic the mammalian cellular environment, and are not suitable for functional studies of the target mammalian protein. Subcloning of mammalian genes into a mammalian promoter-driven expression vector and expressing these genes in a commonly used laboratory cell line such as Chinese hamster ovary cells (CHO), human embryonic kidney 293 cells (HEK 293), HeLa (cervical cancer) cells, and NIH 3T3 (mouse embryonic fibroblast) cells serve well for multiple functional studies. However, this strategy relies on the availability of antibodies that can detect the target protein. Oftentimes, the intended studies are stymied, such as when a newly discovered protein that does not have an antibody for detection, or when the effectiveness or the specificity of an antibody is in question. These difficulties can be circumvented if the target protein is tagged with a short antigenic fragment (i.e., epitope tag) to which an effective antibody is available. Epitope-tagging of a protein also facilitates the purification of the target protein, as antibodies to the epitope tag can be immobilized to matrixes for affinity chromatography.8,9

Expressing and tagging cytosolic mammalian proteins is relatively simple, as expression vectors containing various epitope tags and multicloning sites are widely available. The subcloning process is also straightforward. Expressing and studying membrane proteins in laboratory cell lines, however, is more technically challenging. First, effective antibodies to membrane proteins are often difficult to generate. Second, the majority of membrane proteins possess a signal peptide at their N-termini that directs their co-translational translocation into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) for cell surface expression. Because this short peptide is proteolytically cleaved within the ER, tagging at the N-terminus of a membrane protein requires insertion of the epitope tag between the signal peptide and the mature portion of the membrane protein. Tagging at N-termini is often preferred, especially for Type Ia membrane proteins. Most of eukaryotic membrane proteins with single membrane-spanning regions belong to this class. Since this group of membrane proteins exposes their N-termini on the exterior side of the plasma membrane, tagging at N-terminus may avoid possible functional interference of their C-terminal cytosolic portion, which often serves as the signaling domain. However, since the exterior portion of a membrane protein is often glycosylated to confer full biological functions, whether tagging interferes with this crucial posttranslational modification must be determined.

Vectors containing a signal peptide and an epitope tag have been constructed previously and used in various studies.10–13 However, these vectors were tailored for the expression of individual membrane proteins, and their limited cloning sites cannot accommodate different epitope tags or a variety of targets. Furthermore, some signal peptides are also cytotoxic that leads to mutations, or a lower expression level of the cloned membrane proteins (Lin L, unpublished data). We report here the design, generation, and testing of two sets of mammalian expression modules that tag membrane proteins at their N-termini, using the signal peptide sequence from human receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE). Our results demonstrate that these modules can be universally adapted to subcloning, epitope-tagging, and expressing a variety of mammalian membrane proteins in common laboratory cell lines.

Results

Design of the expression modules

The membrane protein expression module we have designed contains three key components: sequences encoding for the 23-residue signal peptide from human RAGE, followed by either bacteriophage T7 gp10 (12-residue), or FLAG epitope tag (8-residue), and a multicloning site (MCS). The tag was linked to the signal peptide with an EcoRI sequence (GAA TTC) that adds two in-frame amino acids (E and F). Hexameric restriction sequences within the MCS were arranged in tandem without additional nucleotide insertions between hexamers so that an inserted target sequence will be in accordance with the open reading frame of the preceding signal peptide and the epitope tag. In addition to providing a variety of cloning sites, this arrangement also provides a degree of flexibility for the replacement of the epitope tag to suit specific tagging needs: nucleotide sequences of a desired epitope tag can be synthesized to replace the existing tag sequence with a 5′ flanked EcoRI sequence, and a 3′ restriction sequence chosen from the MCS. The entire module was then subcloned into pCDNA3.1 vectors with either neomycin-, or zeocin-resistant markers. A constitutively active promoter from human cytomegalovirus (CMV) in these vectors drives the expression of the tagged membrane protein in mammalian cells. The sequence map of the designed modules is shown in Figure 1, and the available vectors are summarized in Table I.

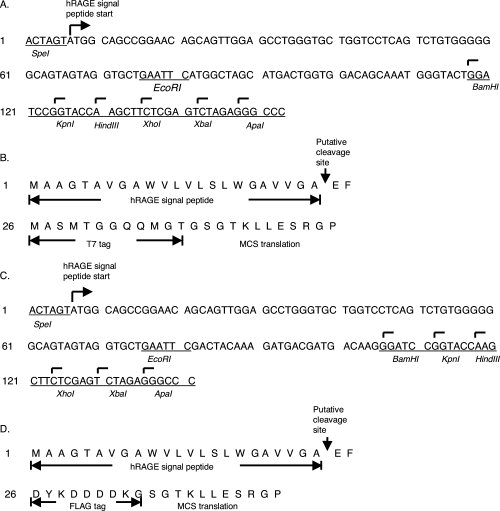

Figure 1.

Nucleotide and amino acid sequences of the designed modules. (A) Nucleotide sequence of the T7 epitope tag module. Hexamer sequences that are recognized by restriction enzymes are marked at the top of the first base and labeled beneath with name of the enzyme. The ApaI (GGGCCC) site is acquired after ligation with pCDNA3.1 vector as an additional in-frame cloning site. (B) Peptide sequence of the T7 eptitope tag module. Amino Acids corresponding to the human RAGE signal peptide, T7 tag, and MCS sequences are marked. (C) Nucleotide sequence of the FLAG epitope tag module. Similar markings are used as in A. (D) Peptide sequence of the FLAG epitope tag module. Amino Acids corresponding to the human RAGE signal peptide, FLAG tag, and MCS sequences are marked.

Table I.

Expression Vectors That Harbor Designed Membrane Targeting and Epitope-Tagging Modules

| Vector name | Backbone | Epitope tag | Antibioticsa | Size (bp)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pJP001 | pCDNA3.1 | FLAG | Neomycin | 5473 |

| pJP002 | pCDNA3.1 | T7 | Neomycin | 5485 |

| pJP007 | pCDNA3.1 | FLAG | Zeocin | 5060 |

| pJP008 | pCDNA3.1 | T7 | Zeocin | 5072 |

All vectors contain an ampicillin resistance gene.

bp: base pair.

Type Ia membrane proteins are successfully expressed from the designed modules

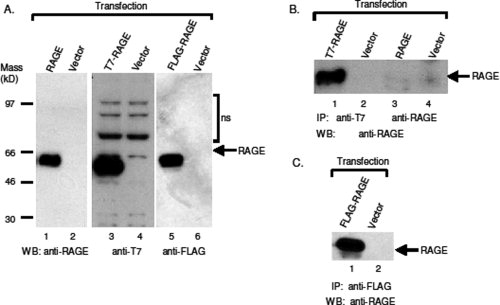

To test whether the designed module can successfully tag and express Type Ia membrane proteins in mammalian cells, we first tested human RAGE. The nucleotide coding sequence of the mature portion of RAGE (starting from residue 24) was amplified with polymerase chain reactions (PCR), and subcloned into vectors pJP007 (FLAG tag) and pJP008 (T7 tag). The expression vectors carrying the test gene were then transfected into CHO-CD14 cells, and cell lysates were prepared for SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), followed by western blotting with either anti-T7, or anti-FLAG antibodies. As shown in Figure 2(A) (Lanes 3–6), both anti-T7 and anti-FLAG antibodies readily detect tagged RAGE proteins, suggesting that the RAGE signal peptide is cleaved correctly within the ER, and that the integrity of the epitope tag is maintained. Although a commercial anti-RAGE antibody detects RAGE in Western blot [Fig. 2(A), Lanes 1 and 2] and is effective in immunostaining (data not shown), it does not immunoprecipitate RAGE [Fig. 2(B), Lanes 3 and 4], suggesting that this anti-RAGE antibody is unable to bind sufficiently tight to the natural form of RAGE. Both anti-T7 [Fig. 2(B), Lane 1] and anti-FLAG [Fig. 2(C), Lane 1] antibodies successfully immunoprecipitated tagged RAGE, demonstrating that this tagging strategy can be employed to study interactions between membrane proteins, or between a membrane protein and cellular proteins, via immunoprecipitation.

Figure 2.

Detection of epitope-tagged human RAGE by western blotting and immunoprecipitation. (A) The expressed epitope-tagged RAGE proteins are recognized by antibodies to the tags. Untagged and tagged RAGE constructs were transfected into CHO-CD14 cells, and cell lysates were resolved with SDS-PAGE in 4–12% pre-cast Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen). The transferred membranes were blotted with antibodies to RAGE (Lanes 1 and 2), and either anti-T7 antibodies (Lanes 3 and 4) or anti-FLAG antibodies (Lanes 5 and 6). WB, western blotting. (B) Anti-T7 antibodies immunoprecipitate (IP) T7-tagged RAGE. T7-tagged RAGE constructs were transfected into CHO-CD14 cells, and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with either anti-T7 (Lanes 1 and 2) or anti-RAGE antibodies (Lanes 3 and 4), and the precipitants were blotted with anti-RAGE antibodies. To avoid recognition of immunoglobulin from primary antibodies used for IP in western blotting, mouse anti-T7 and goat anti-RAGE antibodies were used for IP, whereas rabbit anti-RAGE antibodies were used for WB. (C) Anti-FLAG antibodies immunoprecipitate FLAG-tagged RAGE. Mouse anti-FLAG (M2) antibodies were used for IP, and rabbit anti-RAGE antibodies were used for WB.

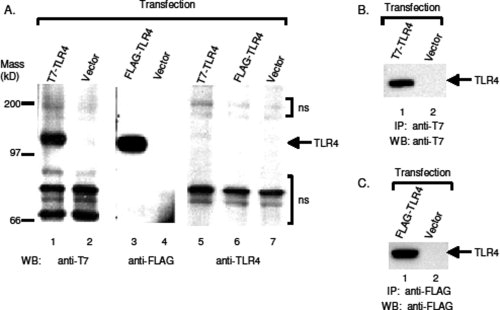

To test whether the designed module can be applied to Type Ia membrane proteins other than RAGE, we tested another Type Ia membrane protein, the human Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), which has a larger molecular mass than RAGE. The nucleotide coding sequence of the mature portion of TLR4 (starting from residue 25) was amplified by PCR, and subcloned into pJP007 and pJP008 vectors. The resultant constructs were then expressed in CHO-CD14 cells. Although a commercial anti-TLR4 antibody was able to detect the expressed TLR4 at cell surface via immunostaining [Fig. 4(D)], it was unable to detect the expressed full-length TLR4 in cell lysates by western blotting [Fig. 3(A), Lanes 5 and 6]. Both anti-T7 [Fig. 3(A), Lane 1] and anti-FLAG [Fig. 3(A), Lane 3] antibodies readily detected the tagged TLR4 in Western blots. Similar to the tagged RAGE, both anti-T7 [Fig. 3(B), Lane 1] and anti-FLAG [Fig. 3(C), Lane 1] antibodies also successfully immunoprecipitated tagged TLR4. Together, these results demonstrate that, in our designed modules, Type Ia membrane proteins can be successfully expressed in laboratory cell lines with the addition of an effective epitope tag at their N-termini for the intended studies.

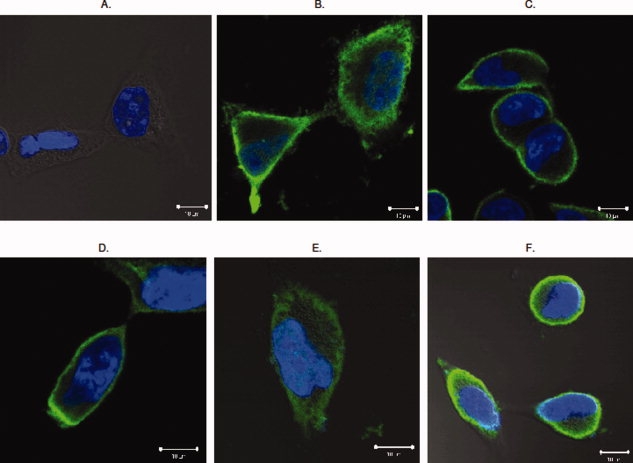

Figure 4.

Epitope tagged RAGE and TLR4 are expressed at cell surface. Both tagged RAGE and TLR4 were transfected into HEK293 cells and immunohistochemistry was performed as described. (Panel A) Negative control. Vector-transfected HEK 293 cells stained with anti-T7 and anti-FLAG antibodies. (Panel B) T7-RAGE transfected HEK 293 stained with anti-T7 antibodies. (Panel C) FLAG-RAGE transfected HEK 293 stained with anti-FLAG antibodies. (Panel D) FLAG-TLR4 transfected HEK 293 cells stained with anti-TLR4 antibodies. (Panel E) T7-TLR4 transfected HEK 293 cells stained with anti-T7 antibodies. (Panel F) FLAG-TLR4 transfected cells stained with anti-FLAG antibodies. Green fluorescence marks immunostaining of the target protein, whereas DAPI blue stains the nucleus. Each representative image was selected from at least three independent staining experiments.

Figure 3.

Tagged human TLR4 were expressed and detected by antibodies to the epitope tags. Human TLR4 were subcloned into vectors carrying epitope modules and expressed in CHO-CD14 cells. Cell lyasates were prepared, and resolved with 4–12% Bis-Tris SDS-PAGE. (A) Antibodies to epitope tags detect the expressed TLR4 with western blotting. Lanes 1 and 2, WB of T7-TLR4 by anti-T7 antibodies; Lanes 3 and 4, WB of FLAG-TLR4 by anti-FLAG antibodies; Lanes 5−7, WB of T7- and FLAG-TLR4 by anti-TLR4 antibodies. ns, non-specific. (B) Immunoprecipitation of T7-TLR4 by anti-T7 antibodies. Tranfected cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with rabbit anti-T7 antibodies and western blotted with mouse anti-T7 antibodies. (C) Immunoprecipitation of FLAG-TLR4 by anti-FLAG antibodies. FLAG-tagged TLR4 was expressed in CHO-CD14 cells and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with mouse anti-FLAG (M2) antibodies and western blotted with mouse anti-FLAG antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP).

The epitope-tagged type Ia membrane proteins are expressed at cell surface

Since we extracted tagged RAGE and TLR4 from unfractionated cell lysates for western blotting studies, it is unclear whether the expressed proteins are correctly localized at the cell surface. To examine the localization of expressed Type I membrane proteins, we chose HEK293 cells as the experimental system because CHO cells are morphologically small and hence difficult for microscopic observations. HEK293 cells, in contrast to CHO cells, are large and have clearly defined plasma membrane structures. The tagged RAGE and TLR4 were transfected into HEK293 cells, and immunohistochemical analyses were performed with confocal microscopy. As shown in Figure 4, both tagged RAGE (Panels B and C) and TLR4 (Panels E and F) are predominantly expressed at cell surface, suggesting that tagging will not affect cellular localization of Type Ia membrane proteins.

The epitope-tagged type Ia membrane proteins are glycosylated and maintain their biological functions

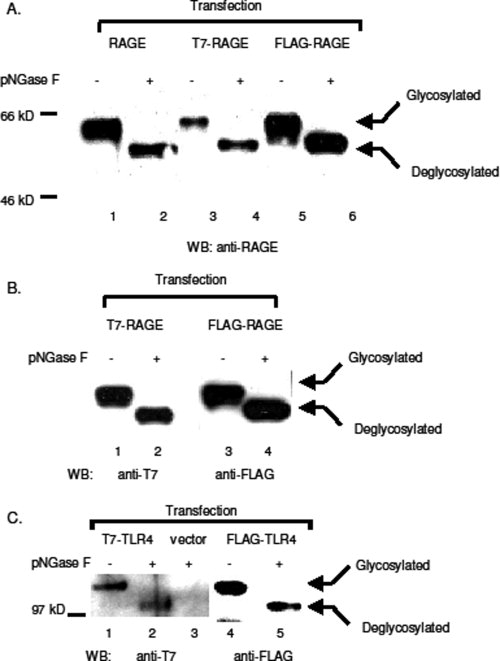

Mammalian membrane proteins are universally glycosylated to pertain their biological functions.14–16 Both RAGE and TLR4 contain two putative N-glycosylation consensus sequences (i.e., NXS/T, as X represents any amino acid), and one of the glycosylation consensus sites of RAGE locates at the second residue of the mature protein (QNIT) that is in the vicinity of the N-terminal epitope tag. To test whether tagging interferes this posttranslational modification, we treated lysates prepared from transfected CHO-CD14 cells with Flavobacterium menigosepticum N-glycosidase (PNGase F) that cleaves glycan chains from membrane proteins. Similar to untagged RAGE, both FLAG-, and T7-tagged RAGE showed mobility shift on SDS-PAGE detected by either anti-RAGE antibodies [Fig. 5(A)], or anti-epitope tag antibodies [Fig. 5(B)], suggesting that tagging does not interfere the N-glycosylation of RAGE. Parallel results were obtained from the tagged TLR4 [Fig. 5(C)].

Figure 5.

Glycosylation of tagged RAGE and TLR4. Tagged and untagged RAGE and TLR4 were expressed in CHO-CD14 cells. Cell lysates were treated with pNGase F at 37°C for 1 h and resolved with SDS-PAGE. (A) Western blotting with anti-RAGE antibodies. Cell transfection: Lanes 1 and 2: untagged RAGE; Lanes 3 and 4: T7-RAGE; Lanes 5 and 6: FLAG-RAGE. (B) Western blotting of tagged RAGE with either anti-T7 (Lanes 1 and 2), or anti-FLAG (Lanes 3 and 4) antibodies. (C) Western blotting of TLR4 with either anti-T7 (Lanes 1−3), or anti-FLAG (Lanes 3 and 4) antibodies. Expression vector transfected cell lysates were used as the negative control for anti-T7 antibodies (Lane 3).

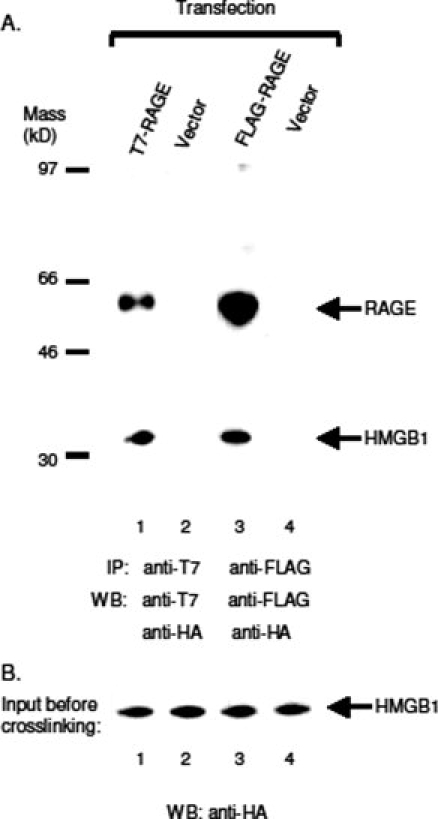

We further tested whether the tagged RAGE still binds its ligand, high mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1). RAGE-transfected CHO-CD14 cells were incubated with HA-HMGB1-transfected cell lysates, and crosslinking reactions were performed with cleavable crosslinker 3,3′-dithiobis(sulfosuccinimidylpropionate) (DTSSP) at cell surface. After crosslinker incubation, anti-tag antibodies were used to immunoprecipitate tagged RAGE. Precipitants were first treated with dithiothreitol (DTT) to cleave the crosslinker, and then resolved with SDS-PAGE. Western blotting was performed with anti-T7 (or anti-FLAG) and anti-HA antibodies to identify crosslinked HMGB1 and RAGE. As shown in Figure 6, both anti-T7 and anti-FLAG antibodies co-immunoprecipitate HMGB1, demonstrating that the tagged receptors maintain their ability for ligand binding. Together, these results suggest that epitope-tagging at N-terminus of a Type I membrane protein does not affect its posttranslational modifications, or its biological functions.

Figure 6.

Tagged RAGE binds its ligand HMGB1. HA-tagged HMGB1 were expressed in CHO-CD14 cells, the cell lysates were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Cells transfected with tagged RAGE were incubated with HA-HMGB1 and crosslinked with DTSSP (2 mM). After crosslinking, the cells were lysed, and immunoprecipitated with antibodies to the tag. The precipitants were cleaved in LDS loading buffer containing 200 mM DTT at 80°C for 10 min before subject to SDS-PAGE. (A) Lanes 1 and 2: Western blotting of immunoprecipitants with anti-T7 and anti-HA antibodies. Rabbit anti-T7 antibodies were used for IP, and mouse anti-T7 and rat anti-HA (3F10, HRP conjugate) were used for WB. Lanes 3 and 4: Mouse anti-FLAG (M2) antibodies were used for IP, and mouse anti-FLAG (M2, HRP conjugate) and rat anti-HA (3F10, HRP conjugate) were used for WB. (B) HA-HMGB1 input. WB, anti-HA antibodies (3F10, HRP conjugate).

The designed vectors also tag, and enhance the expression of type III membrane proteins

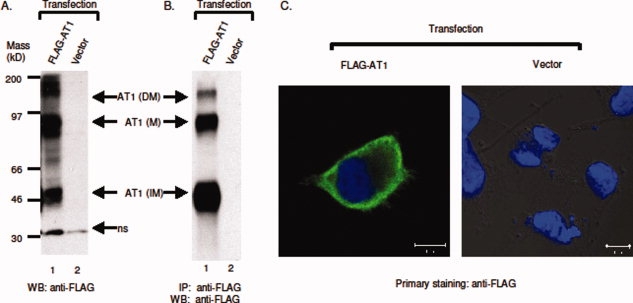

Type III membrane proteins have multiple transmembrane domains in a single polypeptide chain. This group is further divided into two subtypes: Type IIIa membrane proteins contain cleavable signal peptide sequences, whereas those in Type IIIb are synthesized without signal peptides.17 How Type IIIb membrane proteins are translocated to plasma membrane remains unclear. G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) are the major drug intervention targets, and among GPCRs, many belong to the Type IIIb membrane protein subclass. It has been demonstrated that converting a Type IIIb membrane protein, β2-adrenergic receptor, into a Type IIIIa version by introducing a cleavable signal peptide sequence at its N-terminus, enhances the expression of the receptor.10 Here, we test whether the designed modules can also effectively express human angiotensin II receptor 1 (AT1), a Type IIIb GPCR.

The coding sequences of human AT1 were subcloned into pJP007 vector, and the resultant constructs were transfected into CHO-CD14 cells for expression. A commercial anti-AT1 antibody neither detected AT1 in western blotting, nor did it immunoprecipitate AT1 from cell lysates (data not shown). However, FLAG-tagged AT1 was readily detected and immunoprecipitated by anti-FLAG antibodies [Fig. 7(A,B)]. Unlike Type Ia membrane proteins that are uniformly glycosylated, Type IIIb membrane proteins are expressed as both glycosylated (or mature, with an apparent molecular mass of 80 kD) and unglycosylated (or immature, with molecular mass of 41 kD) forms.18,19 Anti-FLAG antibodies also detect expressed AT1 at the cell surface [Fig. 7(C)]. Similar results were obtained for T7-tagged AT1 (data not shown). Together, these results suggest that, like Type I membrane protein, our designed module can also effectively tag, and express Type IIIb membrane proteins in laboratory cell lines.

Figure 7.

Expression of FLAG-tagged AT1. (A) Western blotting of FLAG-AT1. Both glycosylated and unglycosylated forms were marked. M, mature AT1; IM, immature AT1; DM, dimerized AT1; ns, non-specific. (B) Immunoprecipitation of FLAG-AT1, IP: mouse anti-FLAG antibodies (M2), WB: mouse anti-FLAG antibodies (M2, peroxidase conjugate). (C) FLAG-tagged AT1 is expressed at cell surface. FLAG-AT1 was transfected into HEK 293 cells and stained with anti-FLAG antibodies as described. Left panel: FLAG-AT1 transfected cell; right panel: vector-transfected cells. Each representative image was selected from at least three independent staining experiments.

Discussion

Membrane proteins constitute about 30% of the entire protein content of cells, and function in various cellular events including solute and ion transport, energy and sensory stimuli transduction, and information processing. They participate in multiple pathophysiological processes and hence are major pharmacological intervention targets. Despite their important roles, compared to cytosolic soluble proteins, membrane proteins remain poorly studied. The recombinant expression of mammalian membrane proteins has been a major stumbling block in efforts to dissect their biological functions and determine their structures.20 One existing obstacle is the lack of effective antibodies to membrane proteins for detection in various biochemical studies. Our designed expression modules that epitope-tag and express cloned mammalian membrane proteins can serve as an effective means to break this bottleneck.

Our membrane-targeting and epitope-tagging modules were designed for versatility that suits various practical tagging and subcloning needs. Since cleavage of the RAGE signal peptide from the mature RAGE protein occurs between amino acids 23 (alanine, A) and 24 (glutamine, Q), to assure that the signal peptide is still cleavable when linked to the tag sequence, the restriction sequence of EcoRI (GAA TTC) was chosen as the link between the signal peptide and the tag. This choice renders the adjacent residue to the 23rd residue of the signal peptide to be glutamic acid (E), and the A–E juncture sufficiently mimics the natural A–Q juncture to ensure a successful proteolytic cleavage within the ER.21 Although we did not sequence the N-termini of the tagged proteins to verify the cleavage of the signal peptide, given that the expressed proteins react to antibodies that recognize the epitope tag, and are correctly localized at the cell surface and glycosylated (Fig. 2–7), our designed modules appear not to interfere the biogenesis of the tagged membrane proteins. Universal adaptation of mammalian membrane proteins into our modules can be achieved by amplification of the coding sequences of the mature portion of the target membrane protein by PCR, with a pair of primers flanked with the chosen restriction sequences from the MCS (see Fig. 1).

On the basis of their topology, integral membrane proteins are divided into five classes.22 Both Type I and II membrane proteins are bitopic, with Type I having its N-terminal portion exposed on the extracellular side of the membrane, and Type II having the opposite orientation. Our modules are particularly adapted for tagging N-termini of Type I membrane proteins, as epitope-tagging the extracellular portion of Type II membrane proteins can be achieved by cloning the full-length gene to a regular expression vector equipped with a C-terminal epitope tag. As demonstrated in Figure 7, our modules can also be applied to polytopic Type III membrane proteins with their N-termini exposed at the extracellular side of the plasma membrane (e.g., GPCRs). The other two classes, lipid chain-anchored and glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored membrane proteins are monotopic. Both types also contain N-terminal signal peptides, and their C-termini are often modified to anchor them to the membrane bilayer,23,24 thereby leaving epitope-tagging at N-termini a more suitable option. We have not tested whether our designed modules can also epitope-tag and express these two classes of membrane proteins. But given that short epitope tagging at N-termini is unlikely to interfere posttranslational modifications and localization of the tested membrane proteins, we expect that our modules can also be applied to monotopic membrane-anchored proteins.

In current studies, we did not encounter significant cytotoxicity from the three tested membrane proteins: RAGE, TLR4, and AT1, and glycosylation and ligand-binding of the tagged receptors also appear to be normal. Depending upon the individual structure, it is possible that a specific epitope tag may affect the folding or modifications of the target membrane protein. Two features of our designed module can help to determine, and perhaps to overcome, this problem. First, since adapting a gene into our designed modules requires a relative simple subcloning process, and the subsequent immunodetection of the cloned membrane protein is effective, these features will facilitate fast testing of posttranslational modifications and ligand-binding capacity of the cloned target membrane protein in common laboratory mammalian cell lines. Biological functions and cellular behaviors of the tagged membrane protein can hence be conveniently determined and studied. Second, if a specific epitope tag indeed interferes the normal biogenesis of the target membrane protein, other available epitope tag sequences can be conveniently adapted into the designed module (see Fig. 1).

Since matrixes immobilized with either anti-T7, or anti-FLAG antibodies are commercially available, affinity-based purification can be carried out to obtain pure membrane proteins for structural, kinetics, and other biochemical studies. The designed module has been used to express, and purify recombinant soluble RAGE (sRAGE) in CHO-CD 14 cell lines. The obtained purified sRAGE has been successfully used for therapeutic studies in animal models (unpublished data). Future modifications of the module include inserting proteolytically cleavable sequences between the epitope-tag and the target protein so that the tag can be removed from the protein after affinity purification.

In addition to transient expression in laboratory mammalian cell lines, multiple applications can be derived from the designed module or the carrier vector. For instance, the subcloned constructs can be used to establish permanent cell lines that stably express the tagged membrane proteins, using antibiotics for selections in accordance with the drug-resistant marker of the vector. Permanent cell lines overcome the low tranfection efficiency that occurs in some genes or cell lines and increase the yield of the target protein.7 The membrane targeting and epitope-tagging module can also be subcloned into viral vectors for a more efficient delivery, and for expression in a wider range of mammalian cell types. Further, the module can be applied to generation of transgenic animals for physiological and pathological analysis, aided by an effective antibody to the epitope tag.

In conclusion, we present here new sets of artificial modules that facilitate subcloning, epitope-tagging, and expression of mammalian membrane proteins. These modules can potentially help to remove existing technical roadblocks and enhance biochemical characterizations and structural genomic studies of mammalian membrane proteins.

Materials and Methods

Enzymes, chemicals, and antibodies

All restriction enzymes, T4 Quick DNA ligase, T4 DNA ligase, PNGase F, vent DNA polymerase, and other PCR reagents were purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA). Chemicals used for buffers were from Fisher Scientific Company (Pittsburgh, PA). Rabbit anti-RAGE (H-300) and anti-AT1 antibodies (N-10), were from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA); mouse anti-FLAG antibodies (M2, and M2 horseradish peroxidase conjugate) were from Sigma-Aldrich Company (St. Louis, MO); mouse anti-T7 tag antibodies were from Novagen-EMD (Gibbstown, NJ), and rabbit anti-T7 tag antibodies were from Chemicon-Millipore (Billerica, MA); mouse anti-TLR4 antibodies were from Imgenex Corp. (San Diego, CA); anti-HA antibodies (3F10, rat peroxidase conjugate, and mouse unconjugated) were from Roche Applied Science (Indianapolis, IN). Crosslinker DTSSP was purchased from Pierce-Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL).

Construction of signal peptide-epitope tag-MCS module

The coding sequences of the human RAGE signal peptide (23 amino acids) were amplified by PCR from a RAGE clone (Origene, Rockville, MD) with primers flanked with a 5′ SpeI sequence and a 3′ EcoRI sequence. This PCR fragment was ligated to synthetic epitope tag sequences flanked with 5′ EcoRI, and 3′ BamHI sequences with T4 Quick DNA ligase at room temperature for 10 min, and the ligated signal peptide-epitope tag fragment was amplified by PCR with 5′ primer to the signal peptide sequence, and 3′ primer to the epitope tag sequence. The resultant fragment was then ligated to the NheI and BamHI sequences in pCDNA3.1 (zeo +) or pCDNA3.1 (neo +) (Invitrogen). The NheI–SpeI ligation results in a sequence, GCTAGT, which is uncleavable by either NheI or SpeI restriction enzymes and hence link the signal peptide sequence permanently to the vector. The synthetic MCS sequence was subsequently inserted between BamHI and XbaI sites to complete the module. The entire module was nucleotide-sequenced to confirm the authenticity.

Subcloning of testing membrane proteins

Full-length RAGE was initially cloned from the human monocyte cell line U937 (ATCC, Manassas, VA) by reverse-transcription and PCR with primers specific to RAGE (L. Lin, unpublished results). Human TLR4 full-length cDNA was a gift from Dr. Michael Smith, Jr., University of Virginia Health System, Charlottesville, VA; and human AT1 full-length cDNA was provided by Dr. Iekuni Ichikawa, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN. The coding sequences of the mature portion of membrane proteins were amplified with PCR and inserted between BamHI and XbaI sequences in the designated vector. For RAGE subcloning, a BglII sequence was used to ligate to BamHI sequence in the vector to avoid the internal cleavage of the RAGE cDNA sequence by BamHI. All constructed expression vectors carrying testing membrane protein were nucleotide-sequenced and confirmed.

Culture and transfection of laboratory cell lines

CHO-CD14 cell line was obtained from Dr. Peter Tobias, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, and was cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (ATCC). HEK 293 line was from ATCC, and was cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen). For western blotting and immunoprecipitation, 5 × 105−106 CHO-CD14 cells were seeded on 35 mm plates the day before transfection, and lipofectAmine or lipofectAmine 2000 (Invitrogen) were used to transfect CHO-CD 14, according to manufacture's instructions. For each transfection, 1−1.5 μg DNA was used. For immunostaining, 6 × 104 HEK293 cells were seeded in four-well glass chamber slide a day before transfection, and 1.25 μg of plasmid DNA was used.

Western blotting and immunoprecipitation

The transfected cells were incubated in 37°C cell incubator for overnight, washed with 1 × phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and lysed with 250 μL ELB buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 0.1% Nonidet P40, 5 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 1 mM phenylmethanesulphonylfluoride, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and protease inhibitor cocktail from Sigma-Aldrich). The lysates were rotated at 4°C for 1–2 h, and were centrifuged with 14,000 rpm for 30 min to obtain supernatants containing extracted membrane proteins for further assays. Protein concentration of the lysates was determined with the BCA protein assay kit from Pierce-Thermo Scientific and 0.5–1 μg of the total protein was used for western blotting analysis as described from previous publications.25,26 Immunoprecipitation was also described previously.25,26

Immunohistochemical analysis

Transfected cells in chamber slides were rinsed with 1 × PBS and fixed in 10% formaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. After fixation, the cells were washed 3 times with 1 × PBS and blotted with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in 1 × PBS for 30 min prior to incubation with primary antibodies in 1% BSA buffer overnight at 4°C. Next day, the cells were washed with 1 × PBS, and incubated with either rabbit anti-mouse, or swine anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate isomer (FITC) (Dako North America, Carpinteria, CA) in 1% BSA buffer for 60 min at room temperature. Following incubation with the secondary antibody, the cells were washed with 1 × PBS and incubated with 4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 1 min for nuclear staining. Finally, the slides were rinsed with 1 × PBS and mounted with mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Immunohistochemical imaging analyses were carried out with LSM-510 confocal microscope (Zeiss).

Deglycosylation reactions

Cell lysates were prepared as described. Lysates containing 4 μg of total protein were denatured with 10 × denaturing buffer (New England Biolabs) at 100°C for 10 min, and supplemented with 10 × G7 buffer from the same kit. The lysates were divided into two portions: PNGase F (500 units/reaction) was added into one portion, and the reaction was performed at 37°C for 1 h, the other portion was supplemented with H2O and incubated at same temperature as the uncut control. The reaction mixture were resolved with SDS-PAGE and blotted with relevant antibodies.

Ligand-binding assays

CHO-CD14 cells were transfected either with tagged RAGE or hemagglutinin epitope (HA)-tagged HMGB1 (L. Lin, unpublished results). HA-HMGB1 transfected cells were lysed with 0.1% Nonidet P40 (NP-40) in 1 × PBS (100 μL/35 mm plate) and then diluted 5 times with 1 × PBS without NP-40. The cell lysates were centrifuged with 14,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C and the supernatant were used for ligand binding experiments. Cells transfected with tagged RAGE were washed twice with 1 × PBS, and incubated with lysates from HA-HMGB1 transfected cells at 4°C for 1 h. Crosslinker DTSSP (in 1 × PBS) was added to the cell with final concentration of 2 mM and the cell was incubated at 4°C for 2 h. The crosslinking reaction was stopped by addition of Tris buffer (pH 7.4) to final concentration of 20 mM and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. Cells were then lysed with 0.1% NP-40 in 1 × PBS (with protease inhibitors) and the lysates were rotated at 4°C for 2 h to extract proteins from membrane. Immunoprecipitations were performed as described with anti-T7-, or anti-FLAG-antibodies. The crosslinkers in precipitants were cleaved with 200 mM DTT (in loading buffer) at 80°C for 10 min, and then resolved with SDS-PAGE. Western blotting analyses were carried out with anti-HA antibodies in combination with either anti-FLAG, or anti-T7 antibodies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Michael Smith, Jr., Iekuni Ichikawa, and Peter Tobias for generously providing reagents. They also thank Drs. Victor Maltsev for discussions, and Harold Spurgeon for helping to prepare figures. J.P. was a recipient of the Barbara A. Hughes Award of Excellence in Biomedical Research from NIA.

References

- 1.Chen YT, Holcomb C, Moore HP. Expression and localization of two low molecular weight GTP-binding proteins, Rab8 and Rab10, by epitope tag. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6508–6512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemas MV, Yu HY, Takeyasu K, Kone B, Fambrough DM. Assembly of Na, K-ATPase α-subunit isoforms with Na, K-ATPase β-subunit isoforms and H, K-ATPase β-subunit. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:18651–18655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molloy SS, Thomas L, VanSlyke JK, Stenberg PE, Thomas G. Intracellular trafficking and activation of the furin proprotein convertase: localization to the TGN and recycling from the cell surface. EMBO J. 1994;13:18–33. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06231.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quon MJ, Guerre-Millo M, Zarnowski MJ, Butte AJ, Em M, Cushman SW, Taylor SI. Tyrosine kinase-deficient mutant human insulin receptors (Met1153–>Ile) overexpressed in transfected rat adipose cells fail to mediate translocation of epitope-tagged GLUT4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5587–5591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grisshammer R, Tate CG. Overexpression of integral membrane proteins for structural studies. Q Rev Biophys. 1995;28:315–422. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500003504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mather JP, Moore A, Shawley R. Optimization of growth, viability, and specific productivity for expression of recombinant proteins in mammalian cells. Methods Mol Biol. 1997;62:369–382. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-480-1:369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freimuth P. Protein overexpression in mammalian cell lines. Genet Eng. 2007;28:95–104. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-34504-8_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jarvik JW, Telmer CA. Epitope tagging. Annu Rev Genet. 1998;32:601–618. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.32.1.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fritze CE, Anderson TR. Epitope tagging: general method for tracking recombinant proteins. Methods Enzymol. 2000;327:3–16. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)27263-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guan XM, Kobilka TS, Kobilka BK. Enhancement of membrane insertion and function in a type IIIb membrane protein following introduction of a cleavable signal peptide. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:21995–21998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobilka BK. Amino and carboxyl terminal modifications to facilitate the production and purification of a G protein-coupled receptor. Anal Biochem. 1995;231:269–271. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.den Hertog J, Hunter T. Tight association of GRB2 with receptor protein-tyrosine phosphatase α is mediated by the SH2 and C-terminal SH3 domains. EMBO J. 1996;15:3016–3027. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou Q, Zhao J, Husler T, Sims PJ. Expression of recombinant CD59 with an N-terminal peptide epitope facilitates analysis of residues contributing to its complement-inhibitory function. Mol Immunol. 1996;33:1127–1134. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(96)00074-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lis H, Sharon N. Protein glycosylation. Structural and functional aspects. Eur J Biochem. 1993;218:1–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spiro RG. Protein glycosylation: nature, distribution, enzymatic formation, and disease implications of glycopeptide bonds. Glycobiology. 2002;12:43R–56R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/12.4.43r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molinari M. N-glycan structure dictates extension of protein folding or onset of disposal. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:313–320. doi: 10.1038/nchembio880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singer SJ. The structure and insertion of integral proteins in membranes. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1990;6:247–296. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.06.110190.001335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lanctot PM, Leclerc PC, Clement M, Auger-Messier M, Escher E, Leduc R, Guillemette G. Importance of N-glycosylation positioning for cell-surface expression, targeting, affinity and quality control of the human AT1 receptor. Biochem J. 2005;390:367–376. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lanctot PM, Leclerc PC, Escher E, Guillemette G, Leduc R. Role of N-glycan-dependent quality control in the cell-surface expression of the AT1 receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;340:395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White SH. The progress of membrane protein structure determination. Protein Sci. 2004;13:1948–1949. doi: 10.1110/ps.04712004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.von Heijne G. Patterns of amino acids near signal-sequence cleavage sites. Eur J Biochem. 1983;133:17–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chou KC, Elrod DW. Prediction of membrane protein types and subcellular locations. Proteins. 1999;34:137–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Resh MD. Trafficking and signaling by fatty-acylated and prenylated proteins. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:584–590. doi: 10.1038/nchembio834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paulick MG, Bertozzi CR. The glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor: a complex membrane-anchoring structure for proteins. Biochemistry. 2008;47:6991–7000. doi: 10.1021/bi8006324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin L, DeMartino GN, Greene WC. Cotranslational biogenesis of NF-kappa B p50 by the 26S proteasome. Cell. 1998;92:819–828. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81409-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fu D, Kobayashi M, Lin L. A p105-based inhibitor broadly represses NF-kappa B activities. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12819–12826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312572200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]