Abstract

Background

Cardiac amyloidosis is characterized by amyloid infiltration resulting in extracellular matrix (ECM) disruption. Amyloid cardiomyopathy due to immunoglobulin light chain protein (AL-CMP) deposition, has an accelerated clinical course and a worse prognosis compared to non-light chain cardiac amyloidoses i.e., forms associated with wild-type or mutated transthyretin (TTR). We therefore tested the hypothesis that determinants of proteolytic activity of the ECM, the matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their tissue inhibitors (TIMPs), would have distinct patterns and contribute to the pathogenesis of AL-CMP vs. TTR.

Methods / Results

We studied 40 patients with systemic amyloidosis: 10 AL-CMP patients, 20 patients with TTR-associated forms of cardiac amyloidosis, i.e. senile systemic amyloidois (SSA, involving wild-type TTR) or mutant TTR (ATTR), and 10 patients with AL amyloidosis without cardiac involvement. Serum MMP-2 and −9, TIMP-1, −2 and −4, brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) values and echocardiography were determined. AL-CMP and SSA-ATTR groups had similar degrees of increased left ventricular wall thickness (LVWT). However, BNP, MMP-9 and TIMP-1 levels were distinctly elevated accompanied by marked diastolic dysfunction in the AL-CMP group vs. no or minimal increases in the SSA-ATTR group. BNP, MMPs and TIMPs were not correlated with the degree of LVWT but were correlated to each other and to measures of diastolic dysfunction. Immunostaining of human endomyocardial biopsies showed diffuse expression of MMP-9 and TIMP-1 in AL-CMP and limited expression in SSA or ATTR hearts.

Conclusions

Despite comparable LVWT with TTR-related cardiac amyloidosis, AL-CMP patients have higher BNP, MMPs and TIMPs, which correlated with diastolic dysfunction. These findings suggest a relationship between light chains and ECM proteolytic activation that may play an important role in the functional and clinical manifestations of AL-CMP, distinct from the other non-light chain cardiac amyloidoses.

Keywords: matrix metalloproteinases (MMP), tissue inhibitors of MMP (TIMP), cardiomyopathy, immunoglobulin light chains, amyloidosis

Introduction

Cardiac amyloidosis, a rare disorder, is characterized by amyloid fibril deposition in the heart, resulting in a restrictive cardiomyopathy that manifests late with heart failure (HF) and conduction abnormalities1–3. Amyloid infiltration leads to extracellular matrix (ECM) disruption resulting in diastolic dysfunction from progressive thickening and stiffening of the myocardium1;4. There are several types of cardiac amyloidoses, which are classified according to the biochemical nature of the amyloid deposit. In “primary” or immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis (AL), fibrils are formed from aggregated subunits (or fragments thereof) of an amyloidogenic monoclonal light chain protein5. Transthyretin (TTR), normally a plasma-circulating protein, can also form amyloid deposits in myocardial tissue. Wild-type TTR is responsible for the cardiomyopathy in age-related senile systemic amyloidosis (SSA). Heritable mutations in TTR (ATTR) can result in cardiac or neuronal deposition of amyloid protein3;6. Of these disease types, AL-cardiac amyloidosis (AL-CMP) has the worse prognosis, an aspect that is seemingly disproportionate to the structural involvement of the amyloid fibril infiltration in the myocardium7. A partial explanation may lie in studies, which demonstrate that light chains derived from patients with AL-CMP have direct effects on cardiomyocyte function, exerting negative inotropic effects and impairing excitation contraction coupling via increased oxidant stress8;9.

An alternative/complementary explanation that has not to our knowledge been explored is whether AL vs. TTR amyloid fibrils differentially alters ECM turnover, a critical process in the heart for proper maintenance of myocyte-myocyte force coupling and proper myocardial function. Therefore, extracellular amyloid fibrils4 have a high likelihood of disrupting the matrix homeostasis. Matrix homeostasis and composition are determined, in part, by collagen degradation, which are under the control of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), a family of zinc-dependent interstitial enzymes, and their tissue inhibitors (TIMPs). In non-amyloid cardiomyopathy, circulating MMPs and TIMPs are associated with progressive myocardial remodeling and dysfunction10–13. We hypothesized that light chain amyloid deposition in the heart would alter the ECM homeostasis, activate the degradation system, and thus contribute to the pathogenesis of AL-CMP, while other forms of cardiac amyloid would result in less ECM activation. We tested this hypothesis indirectly by measuring circulating levels of selected MMPs and TIMPs in 3 patient groups: 1) light chain cardiac amyloidosis (AL-CMP), 2) cardiac amyloidosis due to wild-type TTR (SSA) or mutant transthyretin (ATTR) and 3) light chain amyloidosis featuring renal disease without cardiac involvement (AL-renal).

Methods

Patient data collection

Forty age-matched patients for whom echocardiographic data and serum samples were available were selected for study, based upon amyloid type. Clinical and laboratory evaluations were performed in the Amyloid Treatment and Research Program at Boston Medical Center, between November 2003 and April 2007. All subjects consented to participate in a research study under a protocol approved by the Boston University Medical Center Institutional Review Board. Subjects had biopsy-proven amyloidosis confirmed by positive Congo red staining of tissue specimens. Subjects underwent a medical history and physical examination, routine laboratory tests (e.g., electrolytes, brain natriuretic peptide [BNP], blood count), 24-hour urine collection, 12-lead electrocardiography, chest x-ray examination, and echocardiography with Doppler study. AL amyloidosis is associated with a plasma cell dyscrasia and typical findings include the production of a clonal immunoglobulin light chain in the bone marrow with the presence of light chain in the serum and/or urine. Therefore, all patients were evaluated for a plasma cell dyscrasia by serum and urine immunofixation electrophoresis and by bone marrow biopsy with immunohistochemical examination to determine the presence of a monoclonal population of plasma cells.

Amyloid cardiac involvement was determined by a history of HF with myocardial wall thickening on echocardiogram (without a history of hypertension or valvular disease), low voltage on surface electrocardiogram or by an endomyocardial biopsy specimen that demonstrated amyloid deposits. Clinical HF was determined by history and physical examination followed by New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification of HF severity. AL amyloidosis was excluded if monoclonal plasma cells were absent in the bone marrow and no monoclonal gammopathy was detected in the serum or urine. Once AL amyloidosis was excluded, patients underwent screening for ATTR amyloidosis by isoelectric focusing (IEF) of serum designed to detect the presence of mutant transthyretin14;15. Direct DNA sequencing of the TTR gene validated a positive result by IEF and the specific mutation was identified. If both AL and ATTR were excluded, a diagnosis of SSA was made in the appropriate clinical setting.

Echocardiography

Two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography were performed at baseline as previously described16;17 using the Vingmed Vivid Five System (GE Vingmed, Milwaukee, WI) with a 2.5-Mhz phased-array transducer. Echocardiograms were performed and analyzed in a blinded manner. Measurements of systolic and diastolic chamber dimensions and wall thickness were obtained from 2-D imaging according to the recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography18. LV wall thickness (LVWT) is derived from an average of the interventricular septum and posterior wall thickness. Left ventricular (LV) mass was derived from the formula described by Devereux et al19. 2-D echocardiographic data was analyzed for LV size and function and myocardial characteristics. Adequate Doppler tracings were available for all patients. Left ventricular end-diastolic and -systolic volumes (EDV and ESV, respectively) were calculated from 2-D echocardiographic dimensions as previously validated20: EDV = 4.5 (LV diastolic dimension)2 and ESV = 3.72 (LV systolic dimension)2. These measurements are reliable only in subjects without a regional wall motion, i.e. only validated in symmetrically contracting ventricles with normal ejection fraction20. From these volumes, stroke volume (SV) was estimated as: EDV – ESV. Cardiac output (CO) was calculated as: SV × heart rate. Similarly, relative wall thickness (RWT) was calculated as: (2*PWT)/ LVEDD. Transmitral Doppler LV filling recordings were performed from the apical 4-chamber view and analyzed for diastolic filling indexes, including peak E- and A-wave velocities and their ratio. Tissue Doppler imaging was used to determine the myocardial velocity of the mitral annulus to derive e-prime (e′).

Biomarker Analysis

Blood samples were obtained at the first visit to the Amyloid Treatment and Research Program, prior to initiation of treatment. BNP values were measured, using the ADVIA Centaur assay (Siemans Healthcare Diagnostics), immediately after blood collection as part of routine laboratory testing. Serum samples were kept at −80°C for other assays. Gelatinases (MMP-2 and MMP −9) and tissue inhibitors of MMPs (TIMP-1, TIMP-2) were measured with commercially available ELISA kits from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, (Buckinghamshire, UK) and the TIMP-4 kit from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, USA).

Endomyocardial biopsies (EMB)

Myocardial tissue samples were obtained from the right ventricular septal endomyocardium, in subjects in whom the diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis needed to be made (6–8 samples for each patient). This was performed from the right internal jugular vein with the use of combined fluoroscopic and echocardiographic guidance. Samples were placed in room temperature in a fixative (10% neutral buffered formalin) with a sterile needle. EMB tissue was embedded in paraffin, and serial sections obtained. Congo red staining was performed on 4–6μm sections to confirm amyloidosis. The remaining slides were preserved for immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin sections were deparaffinized, hydrated and blocked with hydrogen peroxide for 10-min. The sections were then rinsed three times in Tween (0.05%) Tris (0.05M) buffer solution (TTBS, DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) prior to applying the primary antibody. Anti-MMP-9 was diluted (1:25) in antibody diluent from Dako and anti-TIMP-1 was diluted (1:50) in antibody diluent from Dako from a stock of 500ug/mL (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Tissue sections and antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C, rinsed three times in TTBS, and incubated in HRP-labeled polymer (DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) for 30-min. They were then rinsed with TTBS, treated with diaminobenzidine (DAB) for ~5-min, rinsed three times with ddH20, and counterstained in Harris' hematoxylin for 30-sec. After counterstaining, sections were rinsed with H20 for 5-min, dipped twice in 0.25% acid alcohol, briefly rinsed in H20, and placed into 1% ammonia for 10–20 sec before dehydrating and mounting the slides. Sections were visualized under bright-field microscopy and images were recorded using an Optronics camera with Bioquant Image software.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are described as mean±standard error or median [interquartile range]. Categorical variables are described as number of patients and percentages. Differences between all 3 groups regarding echocardiography characteristics, BNP, MMPs and TIMPs were determined using ANOVA and Turkey multiple-comparison post-hoc tests, or Kruskal-Wallis test for non-normally distributed variables. Spearman correlation test was used to evaluate the correlation between echocardiographic parameters, hemodynamics, BNP, MMPs and TIMPs. All analyses were conducted using SPSS software, version 11.5 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois).

The authors had full access to and take full responsibility for the integrity of the data. All authors have read and agree to the manuscript as written.

Results

Patient characteristics

Forty patients were included in the study: 10 AL-CMP patients, 20 patients with cardiac amyloidosis due to wild-type TTR (SSA) or mutant transthyretin (ATTR), and 10 patients with AL amyloidosis featuring renal disease without cardiac involvement (AL-renal). One hundred percent of patients were Caucasian in AL-CMP, 75% in SSA-ATTR, and 80% in AL-renal. Additional clinical characteristics for each group are shown in Table 1. Age, BSA and BMI were similar among all groups. Most of the patients were male. Systolic blood pressure (BP) was lowest in the AL-CMP group, but within the normal range. Serum free light chain measurements, revealed a predominance of λ over κ in AL-CMP and AL-renal. In the SSA-ATTR group, patients had a normal serum and urine profile. Renal function was most impaired in the AL-renal group. Almost all patients with cardiac amyloidosis (AL-CMP and SSA-ATTR) had clinical HF symptoms. Many of these patients had severe cardiac thickening and evidence of systolic and diastolic dysfunction.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics

| AL-renal N=10 | AL-CMP N=10 | SSA-ATTR N=20 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 72 ± 1 | 74 ± 2 | 73 ± 1 |

| Gender, male | 5 (50) | 7 (70) | 17(85) |

| BSA (m2) | 1.78 ± 0.07 | 1.82 ± 0.06 | 1.83 ± 0.05 |

| BMI (kg/ m2) | 27 ± 1 | 25 ± 1 | 26 ± 1 |

| Hemodynamics | |||

| Heart rate (beats /min) | 76 ± 5 | 77 ± 4 | 73 ± 2 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 146 ± 9 | 110 ± 4 * | 126 ± 3 *† |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 76 ± 4 | 69 ± 2 | 77 ± 2 |

| Monoclonal protein in serum or urine | |||

| Serum κ/λ | |||

| Kappa (>50%) | 2 (20) | 0 (0) | |

| Lambda (>50%) | 8 (80) | 10 (100) | |

| Kidney involvement | |||

| Nephrotic syndrome (>2.5) | 5 (50) | 2 (20) | 0 |

| Creatinine ≥ 1.5 | 5 (50) | 2 (20) | 1 (5) |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.1 * | 1.1 ± 0.1 * |

| Clinical evidence of cardiac involvement / heart failure | |||

| NYHA > I | - | 10 (100) | 18 (90) |

| IVS thickness ≥ 1.5 cm | 0 | 6 (60) | 17 (85) |

| EF < 50% | 0 | 5 (50) | 9 (45) |

| Restrictive disease (E/A>2.5 and /or lateral e' <5) | 0 | 7(70) | 10 (50) |

BSA = body surface area; BMI = body mass index; NYHA = New York Heart Association; IVS = inter-ventricular septum; EF = ejection fraction.

P <0.05 vs. AL-renal

P <0.05 vs. AL-CMP.

Left ventricle (LV) size, structure and function

The echocardiographic data for all groups is shown in Table 2. The LV mass was significantly higher in the AL-CMP and SSA-TTR groups when compared to AL-renal group, which had no pathological LV wall thickening. Both AL-CMP and SSA-ATTR groups had marked and comparable LV wall thickening and concentric hypertrophy. The average calculated end-systolic volume (ESV) was slightly increased in the SSA-TTR group, demonstrating that non-light chain deposition in the heart is associated with slight LV dilation.

Table 2.

Echocardiography data

| AL-renal N=10 | AL-CMP N=10 | SSA-ATTR N=20 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LV Myocardial characteristics | |||

| LV mass (g) | 144 ± 13 | 226 ± 24 * | 281 ± 20 * |

| LV mass index (g/m2) | 80 ± 5 | 123 ± 11 * | 152 ± 9 * |

| Inter-ventricular septum (cm) | 1.08 ± 0.05 | 1.51 ± 0.08 * | 1.62 ± 0.04 * |

| Posterior wall (cm) | 0.99 ± 0.03 | 1.52 ± 0.09 * | 1.51 ± 0.06 * |

| RWT | 0.48 ± 0.02 | 0.82 ± 0.06 * | 0.72 ± 0.04 * |

| EDV / LV mass (ml/g) | 0.56 ± 0.03 | 0.31 ± 0.03 * | 0.31 ± 0.02 * |

| LV size | |||

| Left atrium (cm) | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 4.0 ± 0.1 * | 4.4 ± 0.1 *† |

| LV EDD (cm) | 4.2 ± 0.2 | 3.8 ± 0.2 | 4.3 ± 0.2 |

| LV ESD (cm) | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 3.3 ± 0.2 * |

| EDV (ml) | 79 ± 6 | 67 ± 6 | 86 ± 7 |

| EDV/ BSA(ml/ m2) | 45 ± 4 | 36 ± 3 | 46 ± 3 |

| ESV (ml) | 25 ± 3 | 34 ± 4 | 42 ± 4 * |

| ESV/ BSA(ml/ m2) | 14.3 ± 1.9 | 18 ± 1.9 | 22.6 ± 2.0 * |

| LV function | |||

| Fractional shortening (%) | 39 ± 2 | 23 ± 2 * | 24 ± 2 * |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 68 ± 2 | 50 ± 3 * | 52 ± 2 * |

| SV (ml) | 54 ± 4 | 33 ± 3 * | 43 ± 3 |

| SV/ BSA(ml/ m2) | 30 ± 2 | 18 ± 1 * | 24 ± 2 *† |

| Cardiac output (l/min) | 4.2 ± 0.5 | 2.5 ± 0.3 * | 3.2 ± 0.2 * |

| Cardiac index (l/min/m2) | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.1* | 1.7 ± 0.1* |

| Mitral Doppler Flow | |||

| E velocity (cm/s) | 69 ± 7 | 94 ± 8 * | 80 ± 8 |

| A velocity (cm/s) | 95 ± 6 | 69 ± 14 | 49 ± 7 * |

| E/A ratio | 0.73 ± 0.05 | 1.83 ± 0.36 * | 2.31 ± 0.35 * |

| DT (ms) | 291 ± 42 | 226 ± 15 | 242 ± 26 |

| IVRT (ms) | 90 ± 9 | 97 ± 7 | 89 ± 5 |

| Tissue Doppler | |||

| e' lateral (cm/s) | 8.2 ± 0.7 | 4.2 ± 0.6 * | 5.2 ± 0.4 * |

| LA Pressure | |||

| E/e' | 9 ± 2 | 25 ± 3 * | 17 ± 2 *† |

LV = left ventricle; RWT = relative wall thickness; LV EDD = end-diastolic diameter; LV ESD = end-systolic diameter; EDV = end-diastolic volume; EDV/ BSA = EDVI; ESV = end-systolic volume; ESV/BSA = ESVI; SV = stroke volume; DT = deceleration time; IVRT = isovolumic relaxation time.

P <0.05 vs. AL-renal

P <0.05 vs. AL-CMP.

In the AL-CMP and SSA-ATTR groups, LV fractional shortening and calculated EF were significantly lower and in the “mildly-abnormal” range. Calculated SV, CO, and cardiac index were all decreased in AL-CMP vs. AL-renal and SSA-ATTR, reflecting impaired hemodynamics with light chain amyloid deposition. There was evidence of diastolic dysfunction in both AL-CMP and SSA-ATTR (increased E/A ratio and lower early diastolic mitral annular motion (e') velocity). The E/e' ratio revealed that left atrial (LA) pressure was significantly higher in AL-CMP.

BNP and ECM proteolytic marker profile

Despite a comparable degree of increased cardiac wall thickness in the AL-CMP and SSA-ATTR groups, AL-CMP patients showed a marked increase in BNP values (2318±773ng/mL), compared to a modest increase observed in the SSA-ATTR group (360±53ng/mL; P<0.01) (Figure 1A). Likewise, TIMP-1 values were increased in AL-CMP (1161±90ng/mL) vs. AL-renal (876±53ng/mL; P=0.01) and SSA-ATTR (912±67ng/mL; P<0.05) (Figure 1B). In contrast, MMP-9 levels were significantly increased in both AL groups (23±6ng/mL for AL-CMP, 18±3 ng/mL for AL-renal) vs. the SSA-ATTR group (10±1ng/mL; P<0.05 vs. AL-CMP and Al-renal) (Figure 1C). The other markers, TIMP-2, TIMP-4 and MMP-2, were not significantly altered in any of the 3 groups (Figure 1D–F).

Figure 1. BNP and the ECM proteolytic marker profile in cardiac and non-cardiac amyloidosis.

A) BNP. * P=0.01 vs. AL-renal; † P<0.01 vs. SSA-ATTR

B) TIMP-1. **P<0.05 vs. AL-renal; ‡ P<0.05 vs. SSA-ATTR

C) MMP-9. ‡ P<0.05 vs. SSA-ATTR

D) TIMP-2

E) TIMP-4

F) MMP-2

Despite a similar clinical course and the lack of light chains in SSA and ATTR cardiac amyloidoses, there is evidence that the mechanism for amyloid deposition in SSA and ATTR may differ21. We compared whether the ECM proteolytic system and BNP levels differed between SSA and ATTR groups. BNP, TIMP-1, TIMP-2, TIMP-4 and MMP-2 were similar between the two groups, whilst MMP-9 levels were higher in the SSA (13.7 ± 6.2 ng/mL) vs. the ATTR group (7.2 ± 4.1 ng/mL; P=0.02). Both set of values were significantly lower than those in the AL-CMP group (23±6 ng/mL).

Correlations between measures of the ECM proteolytic system, BNP and echocardiographically-derived measures of cardiac remodeling

We further evaluated whether we could correlate the degree of LVWT and LV mass and functional impairment to serum concentrations of BNP and markers of the ECM proteolytic system in patients with cardiac amyloid disease (n=30). There were no significant correlations between LV mass or LVWT to BNP, MMPs and TIMPs. Since BNP is increased in cardiac amyloidosis and may reflect cardiomyocyte damage/toxicity, we further evaluated if BNP levels were correlated to ECM proteolytic activation. As shown in Figure 2A–D, there was a positive correlation between BNP levels and MMP-9, TIMP-1, MMP-2 levels and the ratio of MMP-9 /TIMP-1.

Figure 2.

The relationship between BNP and MMP-9 (A), TIMP-1 (B), MMP-2 (C) and MMP-9/TIMP-1 (D). Closed squares represent AL-CMP and open squares represent SSA-ATTR group.

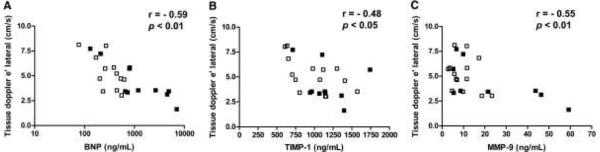

Diastolic function was impaired in both AL-CMP and SSA-ATTR (Table 2). Interestingly, we found a significant negative correlation with e' lateral tissue Doppler (TD) and BNP, TIMP-1 and MMP-9 (Figure 3A–C).

Figure 3.

The relationship between Tissue Doppler e' and BNP (A), TIMP-1 (B) and MMP-9 (C). Closed squares represent AL-CMP and open squares represent SSA-ATTR group.

Myocardial biopsy MMP-9 and TIMP-1 analyses

The presence and abundance of myocardial MMP-9 and TIMP-1 expression from patients with cardiac amyloidosis were investigated in EMB (Figure 4A–C). MMP-9 expression was diffusely increased in AL-CMP (n=5) cardiomyocytes vs. sparse expression in non-light chain cardiac amloidosis (SSA; n=4). In AL-CMP, MMP-9 was visibly absent from the ECM (intersitium), which has been replaced by light chain amyloid deposits. In addition, there was scant MMP-9 expression in the perivascular areas. Likewise, TIMP-1 expression (Figure 4C) was increased in cardiomyocytes and also distributed diffusely throughout the myocardium in AL-CMP vs. SSA hearts.

Figure 4. Immunohistochemical analyses of MMP-9 and TIMP-1 in amyloidotic endomyocardial biopsy.

(A) There is no MMP-9 staining in the normal, non-amyloid heart. MMP-9 expression is more diffuse in AL-CMP than SSA heart biopsies. Solid blue arrows: amorphous amyloid deposition in the ECM – magnification: 100X. (B) MMP-9 expression in AL-CMP and SSA heart biopsies – 400X. Solid black arrows: staining in cardiomyocytes. Dashed back arrows: MMP-9 staining in the interstitium. Red arrow: MMP-9 expression in (+) control. Solid blue arrows: amyloid deposits in the ECM. (C) TIMP-1 expression is more diffuse in AL-CMP than SSA heart biopsies – 400X. Solid arrows: TIMP-1 staining in cardiomyocytes. Dashed arrows: TIMP-1 staining in the interstitium. Red arrow: TIMP-1 expression in (+) control. Solid blue arrows: amyloid deposition in the ECM.

Discussion

This is the first study to evaluate the ECM proteolytic system in different forms of cardiac amyloidosis. Both light chain (AL-CMP) and non-light chain (SSA-ATTR) cardiac amyloidosis resulted in an increased but comparable LV wall thickening and an increase in LV mass. Despite this structural similarity, the presence of cardiotropic amyloidogenic light chains resulted in distinct increases in serum concentrations of BNP, MMP-9 and TIMP-1, which correlated with measures of diastolic dysfunction in AL-CMP. Similarly, increased MMP-9 and TIMP-1 were present in myocardial tissue containing light chain amyloid deposits. These findings suggest a relationship between light chain-amyloid disease and ECM proteolytic activation, which might play a role in the progression of cardiac amyloid disease and the distinct differences in prognosis between these groups of patients.

BNP levels

In cardiac amyloidosis, BNP is released from cardiomyocytes and there is direct evidence of an increase in BNP gene and protein expression in ventricular myocytes22. The inactive pro-form of BNP, NT-proBNP, is elevated in AL-CMP23–25 and appears to precede overt cardiac involvement23. Furthermore, BNP values have been shown to correlate with prognosis25 and response to therapy23–25. In patients with cardiac disease and no amyloid, a good correlation exists between BNP and LVWT, diastolic dysfunction and end-diastolic wall stress26–28. In our study, an interesting finding was that the highest BNP levels were present in the AL-CMP group, despite the fact that the SSA-ATTR group had similar cardiac mass, LVWT and severe diastolic dysfunction. Taken together, these findings suggest that increased BNP in cardiac amyloidosis may reflect not only elevated LV filling pressure22;29, but also the direct cardiac myocyte damage due to extracellular deposition of light chains in AL-CMP8;9;29.

There appears to be a paradoxical relationship between LA size and E/e' in AL-CMP vs. SSA-ATTR groups. The greater LA size but lower E/e' in SSA-ATTR could be explained by a longer duration of cardiac disease, since LA enlargement is a marker of severity and the chronicity of diastolic dysfunction and the magnitude of LA pressure elevation30–32. SSA-ATTR presents in elderly people and has a more insidious course resulting in slowly progressive LA dilatation and by the time they present with HF may have a lower LA pressures (E/e').

MMPs and TIMPs

Similar to cysteine proteinases that degrade the ECM in local areas33, MMPs and their tissue inhibitors (TIMPs) may determine the rate and extent of matrix turnover (i.e., collagen degradation) in the heart. In non-amyloid cardiac remodeling, a relationship has been suggested between wall stress and MMP expression in an experimental model of myocardial infarction34. MMP expression was associated with increased LV end-systolic wall stress34 and MMP inhibition ameliorated adverse structural, cardiac remodeling35. Similarly both MMP-2 and MMP-9 may play a role in cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling36–38.

Distinct patterns of MMP and TIMP expression occur in the LV myocardium of patients with systolic HF and diastolic HF. In patients with diastolic HF from hypertension12 or aortic stenosis39, there is a decreased matrix degradation because of MMP downregulation and TIMP upregulation. In systolic HF, such as in dilated cardiomyopathy, there is increased matrix degradation because of MMP upregulation40. In aortic stenosis, when the LVEF eventually declines, a shift occurs between proteolysis and antiproteolysis41. In our study AL-CMP is associated with increased circulating and myocardial MMP-9 and its inhibitor TIMP-1. Circulating MMP-9 levels are increased in both cardiac and non-cardiac forms of AL amyloidosis. However circulating TIMP-1 levels are increased in only the cardiac form (AL-CMP). This would indicate that perhaps matrix degradation is impaired in the heart and consistent with the above relationship of MMP and TIMP seen in diastolic HF. Interestingly there is no difference in fibrosis from EMB in cardiac amyloidoses (data not shown). Noticeably, other endogenous modulators are responsible for effective matrix destruction, such as cathepsins33, which were not studied here and may play an important role.

Our study suggests that AL-amyloid, and thus light chain cardiac amyloid deposition, is associated with altered markers of matrix turnover (increased circulating MMP-9 and TIMP-1 levels) and increased expression in the myocardium. In AL amyloidosis, the presence of TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 has been observed in pathological sections of liver, kidney and spleen42. It has been proposed that altered expression of MMPs and TIMPs play a role in mesangial remodeling in renal amloidosis43. Light chain deposition alters the cellular redox state in isolated cardiomyocytes, resulting in impairment of cardiomyocyte contractile function and calcium handling8;9. Reactive oxygen species alter myocardial MMP activity through translational and post-translational mechanisms, activating MMPs and decreasing fibrillar collagen synthesis in cardiac cells. Taken together, these data suggest that activation of the ECM proteolytic system observed in AL-CMP might result, at least in part, from light chain toxicity, and contribute to accelerated clinical phenotype and disease progression observed in light chain cardiac amyloidosis.

The present study has several limitations. First, because this is a cross-sectional analysis, it does not allow conclusions regarding cause and effect. Further insight into the role of MMPs and TIMPs in depositional cardiomyopathies might be gained by intervention studies and longitudinal follow-up of patients with cardiac amyloidosis. Second, the sample size is relatively small and it is possible that relationships between BNP and other biomarkers (MMP-2, TIMP-1 and TIMP-4) would be observed in a larger group of subjects. However, our significant findings in this small sample size of patients may serve to highlight the role of these markers. Additionally, other MMP and TIMP species are expressed within the human myocardium but only MMP-2, −9, TIMP-1, −2 and −4 levels were examined in the current study. Third, although AL amyloidosis is a systemic disease and we measured circulating biomarker levels, renal dysfunction could impact those levels, resulting in false-positive findings. However, there was no correlation between renal dysfunction, defined as the presence/absence of renal involvement or as creatinine levels, to BNP levels or ECM proteolytic markers, except for MMP-9, which was increased in both AL groups (data not shown). Moreover, a direct assessment of tissue MMP activity (i.e., zymography) was not performed. Given our positive findings, further studies are required to identify other MMPs and TIMPs that may be altered in AL-CMP patients. Finally, differences in medication that can affect fibrosis across the three groups may be a potential limitation. However, the majority of patients with cardiac amyloidosis were on minimal cardiac medications, and there were no differences in the distribution of the types of medications between the three groups of patients.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that light chain cardiac amyloidosis, despite its structural similarities to other forms of cardiac amyloidosis (SSA or ATTR), results in disproportionate and markedly increased levels of BNP and ECM proteolytic markers, as well as impaired hemodynamics and diastolic dysfunction. These findings may provide insight into the mechanisms for accelerated amyloid disease progression and impaired prognosis associated with light chain cardiac involvement. Future studies will determine whether interventions aimed to interrupt this process may benefit this group of patients.

Cardiac amyloidoses is characterized by amyloid fibril deposition in the heart with extracellular matrix (ECM) disruption and progressive wall thickening and stiffening resulting in a restrictive cardiomyopathy. Systemic amyloidosis featuring cardiac involvement (AL-CMP) is due to immunoglobulin light chain (LC) protein deposition in the heart that may manifests with congestive heart failure (HF), arrhythmias and death within 6 months if untreated. While cardiac amyloidosis may be related to other non-LC proteins i.e. amyloidosis associated with either wild-type transthyretin, senile systemic amyloidois (SSA) or a mutant TTR (ATTR), the prognosis for patients with AL-CMP is worse and the mechanism poorly understood. Direct cardiotoxicity from LCs has been implicated. The current study shows that despite similar structural myocardial involvement (wall thickening and diastolic dysfunction) for both AL amyloidosis and the TTR-related forms, AL-CMP patients had higher brain natriuretic petide (BNP) levels and increased markers of ECM proteolytic activity (MMP-9 and TIMP-1), which were not associated with the degree of wall thickening. Therefore, structural abnormalities by echocardiography may not reflect the severity of AL-CMP. The presence of LCs in AL-CMP, as well as increased levels of BNP and markers of ECM proteolytic activity may reflect additional mechanisms that contribute to the accelerated clinical disease that has been reported. Our findings represent an initial step to increasing our understanding of the pathophysiology of this poorly understood disease. Subsequent steps would focus on the association of these markers with clinical course and prognosis, and whether interventions directed to interrupt these processes would prevent disease progression and improve clinical outcome.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources This work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health HL079099 (to F.Sam), P01 HL68705 (to D.Seldin), and the Gerry Foundation, the Young Family Amyloid Research Fund and the Amyloid Research Fund at Boston University.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures None

References

- 1.Sawyer DB, Skinner M. Cardiac amyloidosis: shifting our impressions to hopeful. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2006;3:64–71. doi: 10.1007/s11897-006-0004-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Selvanayagam JB, Hawkins PN, Paul B, Myerson SG, Neubauer S. Evaluation and management of the cardiac amyloidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:2101–2110. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah KB, Inoue Y, Mehra MR. Amyloidosis and the heart: a comprehensive review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1805–1813. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falk RH, Comenzo RL, Skinner M. The systemic amyloidoses. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:898–909. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709253371306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gertz MA, Comenzo R, Falk RH, Fermand JP, Hazenberg BP, Hawkins PN, Merlini G, Moreau P, Ronco P, Sanchorawala V, Sezer O, Solomon A, Grateau G. Definition of organ involvement and treatment response in immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis (AL): a consensus opinion from the 10th International Symposium on Amyloid and Amyloidosis, Tours, France, 18–22 April 2004. Am J Hematol. 2005;79:319–328. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCarthy RE, III, Kasper EK. A review of the amyloidoses that infiltrate the heart. Clin Cardiol. 1998;21:547–552. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960210804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dubrey SW, Cha K, Skinner M, LaValley M, Falk RH. Familial and primary (AL) cardiac amyloidosis: echocardiographically similar diseases with distinctly different clinical outcomes. Heart. 1997;78:74–82. doi: 10.1136/hrt.78.1.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liao R, Jain M, Teller P, Connors LH, Ngoy S, Skinner M, Falk RH, Apstein CS. Infusion of light chains from patients with cardiac amyloidosis causes diastolic dysfunction in isolated mouse hearts. Circulation. 2001;104:1594–1597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brenner DA, Jain M, Pimentel DR, Wang B, Connors LH, Skinner M, Apstein CS, Liao R. Human amyloidogenic light chains directly impair cardiomyocyte function through an increase in cellular oxidant stress. Circ Res. 2004;94:1008–1010. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000126569.75419.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brower GL, Gardner JD, Forman MF, Murray DB, Voloshenyuk T, Levick SP, Janicki JS. The relationship between myocardial extracellular matrix remodeling and ventricular function. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;30:604–610. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Webb CS, Bonnema DD, Ahmed SH, Leonardi AH, McClure CD, Clark LL, Stroud RE, Corn WC, Finklea L, Zile MR, Spinale FG. Specific temporal profile of matrix metalloproteinase release occurs in patients after myocardial infarction: relation to left ventricular remodeling. Circulation. 2006;114:1020–1027. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.600353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed SH, Clark LL, Pennington WR, Webb CS, Bonnema DD, Leonardi AH, McClure CD, Spinale FG, Zile MR. Matrix metalloproteinases/tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases: relationship between changes in proteolytic determinants of matrix composition and structural, functional, and clinical manifestations of hypertensive heart disease. Circulation. 2006;113:2089–2096. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.573865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spinale FG. Myocardial Matrix Remodeling and the Matrix Metalloproteinases: Influence on Cardiac Form and Function. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:1285–1342. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Connors LH, Ericsson T, Skare J, Jones LA, Lewis WD, Skinner M. A simple screening test for variant transthyretins associated with familial transthyretin amyloidosis using isoelectric focusing. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1407:185–192. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(98)00037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Theberge R, Connors L, Skare J, Skinner M, Falk RH, Costello CE. A new amyloidogenic transthyretin variant (Val122Ala) found in a compound heterozygous patient. Amyloid. 1999;6:54–58. doi: 10.3109/13506129908993288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kotlyar E, Vita JA, Winter MR, Awtry EH, Siwik DA, Keaney JF, Jr., Sawyer DB, Cupples LA, Colucci WS, Sam F. The relationship between aldosterone, oxidative stress, and inflammation in chronic, stable human heart failure. J Card Fail. 2006;12:122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sam F, Halickman I, Vita JA, Levitzky Y, Cupples LA, Loscalzo J, Allensworth-Davies D. Predictors of improved left ventricular systolic function in an urban cardiomyopathy program. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:1622–1626. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schiller NB, Shah PM, Crawford M, DeMaria A, Devereux R, Feigenbaum H, Gutgesell H, Reichek N, Sahn D, Schnittger I. Recommendations for quantitation of the left ventricle by two-dimensional echocardiography. American Society of Echocardiography Committee on Standards, Subcommittee on Quantitation of Two-Dimensional Echocardiograms. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1989;2:358–367. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(89)80014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devereux RB, Alonso DR, Lutas EM, Gottlieb GJ, Campo E, Sachs I, Reichek N. Echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular hypertrophy: comparison to necropsy findings. Am J Cardiol. 1986;57:450–458. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90771-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Simone G, Devereux RB, Ganau A, Hahn RT, Saba PS, Mureddu GF, Roman MJ, Howard BV. Estimation of left ventricular chamber and stroke volume by limited M-mode echocardiography and validation by two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography. Am J Cardiol. 1996;78:801–807. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00425-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bergstrom J, Gustavsson A, Hellman U, Sletten K, Murphy CL, Weiss DT, Solomon A, Olofsson BO, Westermark P. Amyloid deposits in transthyretin-derived amyloidosis: cleaved transthyretin is associated with distinct amyloid morphology. J Pathol. 2005;206:224–232. doi: 10.1002/path.1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takemura G, Takatsu Y, Doyama K, Itoh H, Saito Y, Koshiji M, Ando F, Fujiwara T, Nakao K, Fujiwara H. Expression of atrial and brain natriuretic peptides and their genes in hearts of patients with cardiac amyloidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:754–765. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palladini G, Campana C, Klersy C, Balduini A, Vadacca G, Perfetti V, Perlini S, Obici L, Ascari E, d'Eril GM, Moratti R, Merlini G. Serum N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide is a sensitive marker of myocardial dysfunction in AL amyloidosis. Circulation. 2003;107:2440–2445. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000068314.02595.B2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dispenzieri A, Gertz MA, Kyle RA, Lacy MQ, Burritt MF, Therneau TM, Greipp PR, Witzig TE, Lust JA, Rajkumar SV, Fonseca R, Zeldenrust SR, McGregor CGA, Jaffe AS. Serum Cardiac Troponins and N-Terminal Pro-Brain Natriuretic Peptide: A Staging System for Primary Systemic Amyloidosis. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3751–3757. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dispenzieri A, Gertz MA, Kyle RA, Lacy MQ, Burritt MF, Therneau TM, McConnell JP, Litzow MR, Gastineau DA, Tefferi A, Inwards DJ, Micallef IN, Ansell SM, Porrata LF, Elliott MA, Hogan WJ, Rajkumar SV, Fonseca R, Greipp PR, Witzig TE, Lust JA, Zeldenrust SR, Snow DS, Hayman SR, McGregor CGA, Jaffe AS. Prognostication of survival using cardiac troponins and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide in patients with primary systemic amyloidosis undergoing peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2004;104:1881–1887. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Almenar L, Arnau MA, Martinez-Dolz L, Hervas I, Osa A, Miro V, Sanchez E, Zorio E, Rueda J, Mateo A, Salvador A. Is there a correlation between brain naturietic peptide levels and echocardiographic and hemodynamic parameters in heart transplant patients? Transplant Proc. 2006;38:2534–2536. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.08.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Irzmanski R, Banach M, Piechota M, Kowalski J, Barylski M, Cierniewski C, Pawlicki L. Atrial and brain natriuretic peptide and endothelin-1 concentration in patients with idiopathic arterial hypertension: the dependence on the selected morphological parameters. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2007;29:149–164. doi: 10.1080/10641960701361593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nishikimi T, Yoshihara F, Morimoto A, Ishikawa K, Ishimitsu T, Saito Y, Kangawa K, Matsuo H, Omae T, Matsuoka H. Relationship between left ventricular geometry and natriuretic peptide levels in essential hypertension. Hypertension. 1996;28:22–30. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.28.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nordlinger M, Magnani B, Skinner M, Falk RH. Is elevated plasma B-natriuretic peptide in amyloidosis simply a function of the presence of heart failure? Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:982–984. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Appleton CP, Galloway JM, Gonzalez MS, Gaballa M, Basnight MA. Estimation of left ventricular filling pressures using two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography in adult patients with cardiac disease. Additional value of analyzing left atrial size, left atrial ejection fraction and the difference in duration of pulmonary venous and mitral flow velocity at atrial contraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22:1972–1982. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90787-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simek CL, Feldman MD, Haber HL, Wu CC, Jayaweera AR, Kaul S. Relationship between left ventricular wall thickness and left atrial size: comparison with other measures of diastolic function. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1995;8:37–47. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(05)80356-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsang TS, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ, Bailey KR, Seward JB. Left atrial volume as a morphophysiologic expression of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and relation to cardiovascular risk burden. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:1284–1289. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02864-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sam F, Siwik DA. Digesting the remodeled heart: role of lysosomal cysteine proteases in heart failure. Hypertension. 2006;48:830–831. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000242332.19693.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rohde LE, Aikawa M, Cheng GC, Sukhova G, Solomon SD, Libby P, Pfeffer J, Pfeffer MA, Lee RT. Echocardiography-derived left ventricular end-systolic regional wall stress and matrix remodeling after experimental myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:835–842. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00602-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rohde LE, Ducharme A, Arroyo LH, Aikawa M, Sukhova GH, Lopez-Anaya A, McClure KF, Mitchell PG, Libby P, Lee RT. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibition attenuates early left ventricular enlargement after experimental myocardial infarction in mice. Circulation. 1999;99:3063–3070. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.23.3063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsusaka H, Ide T, Matsushima S, Ikeuchi M, Kubota T, Sunagawa K, Kinugawa S, Tsutsui H. Targeted Deletion of Matrix Metalloproteinase 2 Ameliorates Myocardial Remodeling in Mice With Chronic Pressure Overload. Hypertension. 2006;47:711–717. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000208840.30778.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bergman MR, Teerlink JR, Mahimkar R, Li L, Zhu BQ, Nguyen A, Dahi S, Karliner JS, Lovett DH. Cardiac matrix metalloproteinase-2 expression independently induces marked ventricular remodeling and systolic dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H1847–H1860. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00434.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heymans S, Lupu F, Terclavers S, Vanwetswinkel B, Herbert JM, Baker A, Collen D, Carmeliet P, Moons L. Loss or Inhibition of uPA or MMP-9 Attenuates LV Remodeling and Dysfunction after Acute Pressure Overload in Mice. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:15–25. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62228-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heymans S, Schroen B, Vermeersch P, Milting H, Gao F, Kassner A, Gillijns H, Herijgers P, Flameng W, Carmeliet P, Van de WF, Pinto YM, Janssens S. Increased cardiac expression of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 is related to cardiac fibrosis and dysfunction in the chronic pressure-overloaded human heart. Circulation. 2005;112:1136–1144. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.516963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spinale FG, Coker ML, Heung LJ, Bond BR, Gunasinghe HR, Etoh T, Goldberg AT, Zellner JL, Crumbley AJ. A matrix metalloproteinase induction/activation system exists in the human left ventricular myocardium and is upregulated in heart failure. Circulation. 2000;102:1944–1949. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.16.1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Polyakova V, Hein S, Kostin S, Ziegelhoeffer T, Schaper J. Matrix metalloproteinases and their tissue inhibitors in pressure-overloaded human myocardium during heart failure progression. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1609–1618. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muller D, Roessner A, Rocken C. Distribution pattern of matrix metalloproteinases 1, 2, 3, and 9, tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases 1 and 2, and alpha 2-macroglobulin in cases of generalized AA- and AL amyloidosis. Virchows Arch. 2000;437:521–527. doi: 10.1007/s004280000271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keeling J, Herrera GA. Matrix metalloproteinases and mesangial remodeling in light chain-related glomerular damage. Kidney Int. 2005;68:1590–1603. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]