Abstract

Several primary trials report the adjunctive value of psychoeducational interventions for improving stable angina symptoms, health-related quality of life (HRQL) and psychological well-being; however, few high-quality meta-analyses have examined the overall effectiveness of these interventions. We used meta-analysis in order to determine the effectiveness of psychoeducational interventions for improving symptoms, HRQL and psychological well-being in stable angina patients. Seven trials, involving 949 participants total were included. Those who received psychoeducation experienced nearly 3 less angina episodes per week, delta (Δ)= -2.85, 95% CI, -4.04 to -1.66, and used sublingual (SL) nitrates approximately 4 times less per week, Δ= -3.69, 95% CI -5.50 to -1.89, post-intervention (3-6 months). Significant HRQL improvements (Seattle Angina Questionnaire) were also found for physical limitation, Δ= 8.00, 95% CI 4.23 to 11.77, and disease perception, Δ= 4.46, 95% CI 0.15 to 8.77, but CIs were broad. A pooled estimate of effect on psychological well-being was not possible due to heterogeneity of measures. Psychoeducational interventions may significantly reduce angina frequency and decrease SL nitrate use in the short-term. These encouraging results must be interpreted with caution due to heterogeneity in methods and small samples. Larger, robust trials are needed to further determine the effectiveness of psychoeducation for stable angina management.

Key Words: Stable angina, psychoeducation, angina symptoms, health-related quality of life, psychological well-being, meta-analysis.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic stable angina (CSA) pectoris is a ubiquitous and cardinal symptom of ischemic heart disease (IHD) characterized by pain or discomfort in the chest, upper abdomen, back, arm(s), shoulders, neck, jaw and/or teeth [1]. Angina is considered stable if symptoms are experienced over several weeks in the absence of major deterioration [2]. Stable angina symptomatology can vary depending on factors such as demand for increased myocardial blood flow, stress, emotions, diet and weather, and may range from Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) Class I to Class III angina [3].

Evidence suggests that greater than 64% of patients with CSA are taking more than 1 cardiovascular drug to treat their symptoms [4]. Despite this, angina persists in more than 90% of patients [5]. CSA is distressing, with a well-documented, major negative impact on health-related quality of life (HRQL). Individuals with CSA often live with recurrent pain episodes, poor general health, impaired role functioning, activity restriction, and reduced capacity for self-care [6-18]. These patients are also at risk for acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and stroke [19], as well as increased risk of cardiovascular-related mortality or hospitalization (men: RR 1.62, women: RR 1.48) [20].

Prevalence data from 1999-2002 suggest that more than 6,500,000 Americans may be living with CSA [21]. In Scotland, CSA prevalence (April 2001-March 2002) has been estimated at 28/1000 men and 25/1000 women [22]. While the prevalence of CSA in Canada has not been studied directly, 36% of Canadians aged 35 – 64 years who reported having a diagnosis of heart disease in a National Population Health Survey (n = 345,000) reported angina symptoms and related daily activity restrictiona. The Canadian Laboratory Centre for Disease Control also found that in 1995, 16% of all physician visits related to heart disease in Canada (29.6 million visits) involved a complaint of anginab.

CSA also imposes numerous direct and indirect societal costs. A recent economic pilot study by McGillion et al. (2006, [published abstract]) found that the total median annualized societal cost of CSA was $12,615 (Canadian) per person (2003 – 2005); indirect costs accounted for 2/3 of the total CSA-related cost of illness [23] In the UK, the direct cost of CSA in 2000, including prescriptions, admissions, outpatient referrals, and procedures, was estimated at ₤669, 000, 000, accounting for 1.3% of the total National Health Service expenditure [24].

Considering the available data on prevalence, impact, health service utilization and costs, CSA is a major and debilitating health problem. National guidelines are readily available that summarize the best evidence about pharmacological and percutaneous coronary interventions for improvement of angina symptoms and related HRQL [25, 26]. While several primary studies report the value of psychoeducational interventions as an adjunctive means of improving CSA symptoms, HRQL and psychological well-being [27-33], no high-quality syntheses, using meta-analytic techniques, have been conducted to examine the effectiveness of these particular interventions. Psychoeducational interventions are multi-modal treatment packages that employ learning materials and cognitive-behavioural strategies to achieve changes in knowledge and behaviour for effective disease self-management [34]. They target day-to-day problems that patients encounter such as pain, fatigue, decreased mobility and endurance, anxiety and stress [34]. Over a course of several days or weeks, an array of self-management techniques are taught that patients can rehearse and incorporate into their daily routines, such as a) safe exercise habits, b) energy conservation, pacing, and sleep quality enhancement, and c) communication and decision making skills. Psychoeducation programs can vary, ranging from individual to group-based formats, with either prescriptive or flexible curricula. More flexible programs allow for a choice of self-management technique(s) that best suit one’s personality, lifestyle, ability, and confidence level [35]. Irrespective of format, a firm grounding in social, cognitive and/or behavioural theories is critical to the success of most psychoeducation programs [33-40]. These theories, such as Bandura’s Self-Efficacy Theory, target patients’, a) confidence to achieve optimal functioning, b) acceptance of their chronic illness-induced limitations, and c) more adaptive ways of thinking, feeling and behaving [33-40]. A recent review of psychoeducation trials across divergent chronic illness populations found that adherence to self-efficacy enhancing principles consistently resulted in improved knowledge, performance of self-management behaviours, and various aspects of physical and emotional functioning such as exercise capacity and mood status [35].

To date, most psychoeducation programs designed specifically for patients with CSA have targeted confidence in angina self-management, reduction of angina symptoms and related sublingual (SL) nitrate use, as well as improvements in HRQL. Yet, existing reviews of these programs are either narrative-based [41], or have examined the effectiveness of a broad array of psychological interventions, with or without conventional cardiac rehabilitation, for general coronary artery disease populations [42].

OBJECTIVES

To determine the effectiveness of psychoeducational interventions for improving angina symptoms, HRQL, and psychological well-being for patients with CSA.

CRITERIA FOR SELECTION OF STUDIES INCLUDED IN THIS REVIEW

Study Designs

All published and unpublished randomized controlled trials of psychoeducational interventions delivered by a trained professional in individual or group formats, with parallel designs; follow up period varied. Non-randomized studies and single-group design studies were excluded.

Participants

Adult outpatients of all ages with CAD and Canadian Cardiovascular Society Class I – III angina, experiencing stable symptoms for at least 6 months.

Types of Interventions and Controls

Psychoeducational interventions employing a combination of cognitive and behavioural angina self-management techniques such as energy conservation, pacing, anxiety and stress management or counselling, exercise, dietary planning, safe SL nitrate use, and relaxation training. Controls received routine or usual care and were not exposed to the intervention during the study period.

Outcomes Measures

Angina symptom profile including angina frequency and duration, and related SL nitrate use

Self-reported HRQL

Psychological well-being, reflected by anxiety, stress and/or depression

SEARCH METHODS FOR IDENTIFICATION OF STUDIES

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, PubMed, CINHAL, EMBASE, Proquest Dissertation Abstracts, Psychinfo and HealthStar, Jan 1990 – Oct 2006, using combinations of key medical subject heading (MeSH) terms including chronic stable angina, angina pectoris, psychoeducation, psychosocial factors, stress/prevention and control, patient education, education randomized controlled trials, and clinical trials. We also conducted hand searches of relevant journals, proceedings of major conferences, and secondary references; experts in the field were consulted for additional sources. We planned to contact authors where possible to obtain missing information. Our search strategy was critiqued and replicated by an external information specialist to ensure comprehensiveness.

METHODS

Final Selection of Trials

Three reviewers reached consensus on all trials to be included in this analysis by reviewing the titles, abstracts and reports of all trials according to the inclusion criteria specified a priori; individual trial results were not considered during this process.

Data Extraction and Appraisal of Methodological Quality

Two reviewers participated in independent extraction of process and outcome data from each trial according to a standardized format used in a prior review [41]. The quality of included trials was assessed by three reviewers with respect to sample size, generation of randomization sequence, allocation concealment, standardized intervention delivery, reliability and validity of measurement instruments and response rate (RR), blinding of outcome assessment, and examination of group differences.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

All outcomes examined in this study were continuous in nature. For all relevant outcome data, weighted mean differences (WMD) and associated 95% confidence intervals were calculated [43] using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 2, © Biostat. Inc. and verified using SAS/STAT® SOFTWARE. WMDs were calculated via the inverse variance method wherein the weight for each primary trial was determined by the inverse of the variance of its respective effect estimates [43]. Mean change scores were taken from the results of each study except one (Payne et al. 1994), in which mean change in angina frequency had to be estimated from graphical output. Standard deviations for mean change scores were taken directly from the results where available, or calculated using the mean change score, the test-statistic (e.g. F value) and the sample size. The follow-up period for relevant outcomes was short-term (up to 12 weeks) for most trials (Bundy et al., 1994; Gallacher et al., 1997; Lewin et al., 1995; Payne et al., 1994; McGillion et al., 2006), and extended to 24 weeks in one trial (Lewin et al., 2002). Therefore, sensitivity analyses for all outcomes were conducted including and excluding the maximum follow-up period; length of follow-up period did not significantly affect the direction of pooled estimates of effects or statistical significance.

With respect to angina symptom profile, one trial (McGillion et al. 2006 [published abstract]) did not use a symptom diary. Instead, the authors employed the Seattle Angina Questionnare (SAQ) [44] to collect 4 week angina frequency and nitrate use on 6 point scales where the response categories were: 1 = 4 or more times per day; 2 = 1 to 3 times per day; 3 = 3 or more times per week, but not every day; 4 = 1 to 2 times per week; 5 = less than once a week; 6 = none over the past 4 weeks; we had access to these original raw data. To enable the calculation of mean differences in angina frequency and nitrate use for meta-analysis, participants’ responses were recoded as weekly estimates where: 1 = 28 times per week; 2 = 14 times per week; 3 = 4 times per week; 4 = 2 times per week; 5 = 0.5 times per week; and 6 = 0 times per week. The original data and the recoded data were analyzed for congruency in testing the association between the intervention group and the placebo group. Weighted mean differences were then calculated both including and excluding this trial (McGillion et al. 2006) to examine if these approximations changed the overall conclusion; no impact on the significance of the results was found.

DESCRIPTION OF STUDIES

Eight trials, conducted in 7 countries, between 1994 and 2007, and involving 1,009 patients were identified for possible inclusion. One study was excluded that examined the impact of group psychological treatment on patients with non-ischemic chest pain [45]. Six of the included trials reported use of an isolated psychoeducational intervention with components designed to enhance patients’ perceived confidence and skills to manage angina symptoms (Bundy et al., 1994; Gallacher et al., 1997; Lewin et al., 1995; 2002; Payne et al., 1994; McGillion et al., 2006). Control groups received usual medical and/or nursing care as described; no controls were exposed to the intervention during the study period. One trial included a standardized medication regimen for both treatment and control groups (Ma and Teng, 2005).

Details of each included trial are presented in Table 1. Five trials (Bundy et al., 1994; Gallacher et al., 1997; Lewin et al., 1995; Payne et al., 1994; McGillion et al., 2006) tested small-group interventions (6-15 patients) employing varying combinations of educational materials, planned exercise and cognitive-behavioural techniques targeted at lifestyle and symptom self-management, relaxation training or stress reduction, or enhancement of physical activity. Intervention duration, format, and process varied. Two trials tested interventions with content similar to the group-based interventions but on an individual basis (Lewin 2002; Ma and Teng 2005). All trials included baseline assessment of participant characteristics and outcomes prior to randomization. Most trials used symptom diaries to measure angina symptom profile and related SL nitrate use; objective measures of ischemia were less often used. Subjective measures were also most often used to examine HRQL and psychological well-being. Data pertinent to this review were collected up to 24 weeks following baseline (Lewin et al., 2002).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies

| Study | Bundy et al. 1994 |

| Design | RCT |

| Relevant outcomes/definitions | Angina symptoms/severity, frequency, duration, intensity; exercise capacity/bicycle ergometer; anxiety and depression/HADS |

| Sample size (after LTF); participant characteristics; setting; country | N= 29; male and female CSA patients aged 46-63; unclear; Clwyd, UK |

| Measurement occasions; outcome measures: reliability and validity; RR | 8 and 16 weeks post intervention; daily angina diary: not addressed, ergometer: not addressed, HADS: reliable and valid; 100% |

| Method of randomization | Unclear |

| Allocation concealment | Unclear |

| Intervention | Small group 7-week (1.5 hours weekly) program on stress, anger and lifestyle management, problem solving, cognitive control, relaxation training; clinical psychologist intervener |

| Blinding of outcome assessment | Unclear |

| Examination of group differences | Done |

| Notes | Inadequate discussion of intervention controls and description of sample |

| Study | Gallacher et al. 1997 |

| Design | RCT |

| Relevant outcomes/definitions | Chest pain and discomfort/severity, frequency, duration, intensity; stress/DSP |

| Sample size (after LTF); participant characteristics; setting; country | N= 452; male CSA patients, <70 years of age, 87%; unclear; South Glamorgan, Wales |

| Measurement occasions; outcome measures: reliability and validity; RR | Baseline and 6 months post-intervention; 14-day diary of chest pain and discomfort: not addressed, DSP: reliable and valid; 87% |

| Method of randomization | Sequential groups of 8 envelopes (4 in each included in the intervention) |

| Allocation concealment | Unclear |

| Intervention | 3 1-hour biweekly small group sessions on stress management and relaxation techniques; intervener not identified |

| Blinding of outcome assessment | Unclear |

| Examination of group differences | Done |

| Notes | Inadequate discussion of intervention controls; results generalizable to men only |

| Study | Lewin et al. 1995 |

| Design | RCT |

| Relevant outcomes/definitions | Angina/severity, frequency, duration, intensity, nitrate use; disability/SIP; exercise tolerance/ECG treadmill test |

| Sample size (after LTF); participant characteristics; setting; country | N= 65; male and female CSA patients; hospital clinic setting; England |

| Measurement occasions; outcome measures: reliability and validity; RR | Baseline and immediate, 4 months, and 1 year post intervention; angina diary: not addressed, SIP: reliable and valid, ECG: reliable and valid; 87% |

| Method of randomization | Unclear |

| Allocation concealment | Unclear |

| Intervention | 8-week combined small group/individual session rehabilitation program (2 mornings a week) featuring relaxation training, identification of mal-adaptive behaviours, coping strategies, goal setting; clinical psychologist and physiotherapist interveners |

| Blinding of outcome assessment | Unclear |

| Examination of group differences | Done- extensive |

| Notes | Inadequate discussion of intervention controls |

| Study | Payne et al. 1994 |

| Design/Country | RCT |

| Relevant outcomes/definitions | Chest pain/frequency and intensity likert scales; Prevailing mood and psychological stress/ CES-D, STPI |

| Sample size (after LTF); participant characteristics; clinical setting; country | N= 43; male veteran CSA patients < 65 years of age; unclear; USA |

| Measurement occasions; outcome measures: reliability and validity; RR | Sessions 1 and 3, 1 and 6 months follow-up; chest pain likert scales; not addressed, CES-D and STPI: reliable and valid; 83% at 1 month, 67% at 6 months |

| Method of randomization | Based on alternating weekly cohorts |

| Allocation concealment | Unclear |

| Intervention | 3-week small group angina management program, featuring cognitive stress management and relaxation techniques; intervener not identified |

| Blinding of outcome assessment | Unclear |

| Examination of group differences | Done- extensive |

| Notes | Whether allocation was random is unclear; results generalizable to men only |

| Study | Lewin et al. 2002 |

| Design | RCT |

| Relevant outcomes/definitions | Anxiety and depression/HADS; Angina/angina frequency and nitroglycerine use; HRQL/SAQ |

| Sample size (after LTF); participant characteristics; setting; country | N= 130; patients with diagnosis of angina within 1 year, average age: treatment 66.74 (SD 9.37), controls 67.64 (9.01); outpatient clinic; England |

| Measurement occasions; outcome measures: reliability and validity; RR | Baseline and 6 months; angina diary: not addressed, HADS and SAQ: reliable and valid; 91% at 6 months |

| Method of randomization | Randomization by list held at a remote site |

| Allocation concealment | Person responsible for randomization list blinded to patients |

| Intervention | Individualized cognitive-behavioural disease management program featuring structured interview, patient-held workbook, audio-taped relaxation program, angina misconceptions, risk-factor assessment, lifestyle change, telephone support, education sessions; nurse intervener |

| Blinding of outcome assessment | Done |

| Examination of group differences | Done- extensive |

| Notes | |

| Study | McGillion et al. 2006 |

| Design | RCT |

| Relevant outcomes/definitions | HRQL/Medical Outcome Study SF-36, SAQ |

| Sample size (after LTF); participant characteristics; setting; country | N=130; male and female CSA patients, average age 68 (SD 10.6); unclear; Canada |

| Measurement occasions; outcome measures: reliability and validity; RR | Baseline and 3 months; SF-36 and SAQ: reliable and valid; 87% |

| Method of randomization | Centrally-controlled computerized randomization |

| Allocation concealment | Centrally protected by computer |

| Intervention | Small group 6-week self-management program featuring self-efficacy, weekly goal setting, energy conservation, decision making, emotional responses, symptom management techniques, patient workbook, meaning of angina, safe exercise, emergency management, protocol and external auditor used to ensure standardized delivery; nurse intervener |

| Blinding of outcome assessment | Done |

| Examination of group differences | Done- extensive |

| Notes | Contact information: Dr. Michael McGillion, University of Toronto Email: michael.mcgillion@utoronto.ca |

| Study | Ma and Teng 2005 |

| Design | RCT |

| Relevant outcomes/definitions | Anxiety and depression/anxiety and depression charts; angina/24 hour ambulatory ECG |

| Sample size (after LTF); participant characteristics; setting; setting | N= 100; male and female CSA patients, age range/average not given; recruited in cardiology inpatient setting during medical management of angina; China |

| Measurement occasions; outcome measures: reliability and validity; RR | Unclear; anxiety and depression charts: not addressed, 24 hour ambulatory ECG: reliable and valid; 100% |

| Method of randomization | Unclear |

| Allocation concealment | Unclear |

| Intervention | Standardized drug treatment applied to both groups: nitrates, anti-coagulants; Individualized 8- week Beck’s cognitive intervention for treatment group featuring angina review; negative cognitions identification, angina misbeliefs and related home-based work; physician intervener |

| Blinding of outcome assessment | Done |

| Examination of group differences | Done |

| Notes | Translated by Fang Zhang-Helwig, University of Toronto; measurement occasions unclear |

NB: CES-D: Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; DSP= Derogatis Stress Profile; ECG= electrocardiogram; HADS= Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HRQL= health-related quality of life; RCT= randomized controlled trial; RR= response rate; SAQ= Seattle Angina Questionnaire; SD= standard deviation; SIP= Sickness Impact Profile; STPI= Spielberger State-Trait Personality Inventory.

METHODOLOGICAL QUALITY

Sample sizes ranged from 29 to 452; two trials included power analyses to support sample size (Lewin et al., 2002; McGillion et al., 2006). The method of randomization was unclear in three trials (Bundy et al., 1994; Lewin et al., 1995; Ma and Teng, 2005); stated randomization methods included sequential envelopes (Gallacher et al., 1997), alternating weekly cohorts (Payne et al., 1994), external randomization list (Lewin et al., 2002) and centrally-controlled computer-generated randomization (McGillion et al., 2006). Strategies used to preserve concealment of allocation sequence and blinding of outcome assessors were addressed in two trials (Lewin et al., 2002; McGillion et al., 2006). To varying degrees, all trials examined group differences in key baseline characteristics and pretest scores, and response rates across measurement occasions ranged from acceptable to excellent (67% - 100%). Most trials used a patient diary to record angina frequency, duration, intensity and SL nitrate use; the reliability and validity of these tools was not addressed. When measured, HRQL and aspects of psychological well-being were captured using well-established, reliable and valid measures. Only one trial addressed methods used to ensure standardized intervention delivery and adherence to intervention protocol (McGillion et al., 2006). Across trials, intervention delivery was limited to a single site; intervention formats, duration, and processes were variable. The results of two trials were applicable to men only (Gallacher et al., 1997; Payne et al., 1994). Based on our review of methodological quality, the majority of available trials are likely susceptible to a number of biases due the following potential threats to validity: inadequate power (sample size bias), unclear allocation concealment (selection bias) and blinding of outcome assessment (ascertainment bias), inadequate experimental controls (co-intervention), and unknown reliability and validity of measures (insensitive measure bias) [46-51].

RESULTS

Seven trials, involving 949 CSA patients, were included in this review. It was not possible to include results from two trials (Gallacher et al., 1997, n = 452; Ma and Teng 2005; n = 100) in any pooled estimates of effect due to the heterogeneity of their measures and analyses. A summary of the results is presented in Table 2 by outcome, and in sequential order, starting with symptom profiles, followed by HRQL and psychological well-being. Figs. 1-4 present the meta-analysis graphs for significant outcomes respectively. All results pertain to pooled short-term effects, given the maximum length of follow-up of 24 weeks.

Table 2.

Results

| Variable | Difference in Change | 95% CI for Difference | p-value | Effect Size (Cohen’s d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angina Symptom Profile | ||||

| Angina Frequency | -2.85 | [-4.04, -1.66] | <0.001 | 0.49 |

|

Angina Duration Adjusted |

-0.51 -5.86 |

[-0.81, -0.21] [-13.97, 2.25] |

0.001 0.157 |

0.31 0.20 |

| Nitroglycerine Use | -3.69 | [-5.50, -1.89] | <0.001 | 0.53 |

| Self-Reported HRQL | ||||

| SAQ – DP | 4.46 | [0.15, 8.78] | 0.042 | 0.26 |

| SAQ – PL | 8.00 | [4.23, 11.77] | <0.001 | 0.51 |

| SAQ - TS | 2.76 | [-1.47, 6.99] | 0.201 | 0.17 |

|

Psychological Well-Being Pooled estimates of effect not possible | ||||

NB: DP= disease perception; HRQL= health-related quality of life; PL= physical limitation; SAQ= Seattle Angina Questionnaire; TS= treatment satisfaction.

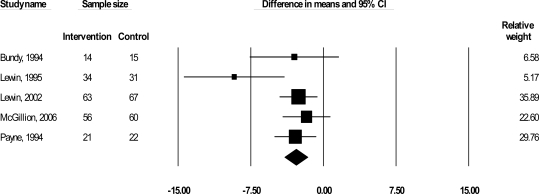

Fig. (1).

WMD in frequency of angina episodes per week.

Angina Symptom Profile

Five trials (Bundy et al., 1994 ; Lewin et al., 1995; 2002; Payne et al., 1994; McGillion et al., 2006) reported on angina frequency (383 patients), which we examined according to mean change in number of angina episodes per week. Results suggested a significant short-term reduction in angina frequency by 2.85 episodes per week, delta (Δ) = -2.85, 95% confidence interval (CI), -4.04 to -1.66, p < 0.001 (Fig. 1). Angina duration was reported in three trials (224 patients) (Bundy et al., 1994; Lewin et al., 1995; 2002) and was examined according to mean change in number of minutes per angina episode. Although results suggested a significant short-term 1/2 minute reduction in angina per episode, Δ = -.51, 95% CI, -.81 to -0.21, p= 0.001, Bundy et al.’s study with a small sample (n = 29) carried 99% of the weight in this analysis due to its small standard deviation. We removed this study from the duration analysis given that a) it was influencing this meta-analytic result so heavily and, b) low variance in scores is unusual for small samples; once removed, the direction of the observed effect remained unchanged yet the summary difference in means was no longer significant: Δ = -5.86, 95% CI, -13.97 to 2.25, p= 0.001.

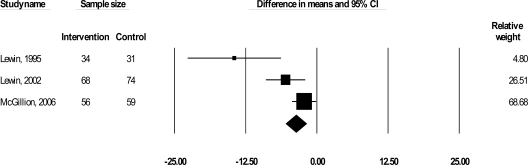

SL nitrate use was also reported in three trials (310 patients) (Lewin et al., 1995; 2002; McGillion et al. 2006) and was examined according to mean change in number of nitroglyercine uses (one use included up to 3 sprays) per week. Psychoeducational intervention resulted in a significant reduction in nitrate use by 3.69 times per week: Δ = -.3.69, 95% CI, -.5.50 to -1.89, p< 0.001 (Fig.2).

Fig. (2).

WMD in sublingual nitrate usages per week.

We could not find any clear a priori evidence of what constitutes clinically significant reductions in angina symptoms and/or sublingual nitrate use. We therefore used Cohen’s d formula for standardized mean differences between groups (d = M1 - M2 / σ) to calculate effect size (ES) as an initial indicator of clinical significance [52]. Effect size estimates for angina frequency and SL nitrate use were 0.49 and 0.53 respectively.

Health-Related Quality of Life

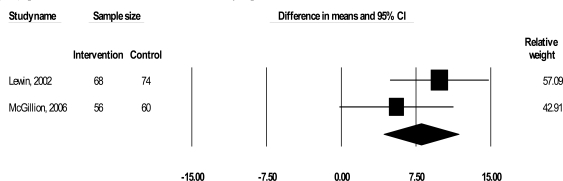

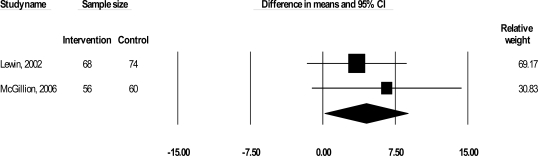

Two trials examined the impact of their interventions on self-reported HRQL (Lewin et al., 2002; McGillion et al., 2006) with the disease-specific SAQ (267 patients) [43]. The SAQ quantifies five clinically relevant domains of disease-specific HRQL including physical limitation (PL), anginal stability (AS), anginal frequency (AF), treatment satisfaction (TS), and disease perception (DP); no overall HRQL summary score is derived [43]. We excluded AF and AS from this analysis as raw SAQ AF and AS-related data (from McGillion et al.’s trial) were factored into our symptom profile analyses. As shown in Figs. 3 and 4, results suggested significant improvements in PL [Δ = 8.00, 95% CI, 4.23 to 11.77, p< 0.001] and DP [Δ = 4.46, 95% CI, 0.15 to 8.77, p= 0.042], but CIs were wide; effect sizes were 0.51 and 0.26 respectively. No significant improvement in TS was found.

Fig. (3).

WMD in angina-induced physical limitation (SAQ-PL) scores (disease-specific health-related quality of life).

Fig. (4).

WMD in disease perception (SAQ-DP) scores (disease-specific health-related quality of life).

Psychological Well-Being

Three trials reported on psychological well-being using the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale and the Spielbeger State-Trait Personality Inventory (Payne et al. 1994), the Derogatis Stress Profile (Gallacher et al. 1997) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (Lewin et al. 2002) respectively; a pooled estimate of effect on psychological well being was not possible due to the heterogeneity of these measures.

DISCUSSION

In this review we have appraised and summarized the results of 7 trials of psychoeducational interventions for CSA management, conducted in 6 different countries, in a variety of outpatient, hospital and community-based settings. The search strategy used to identify these trials was as comprehensive as possible for CSA-specific psychoeducational interventions, without language restrictions.

The first outcome examined was angina symptom profile. Pooling the results of 5 of the included trials suggested that psychoeducational interventions significantly reduce angina frequency and nitrate use, and enhance aspects of disease-specific HRQL in the short term. Angina frequency and nitrate use were decreased by approximately 3 and 4 times per week respectively. These results are encouraging given the high levels of perceived psychological burden and reports of poor quality of life associated with continued angina symptoms [6-18, 53, 54]. Effect size estimates for angina frequency and nitrate use were 0.49 and 0.53 respectively, suggesting that psychoeducation offers moderate short-term positive effects on these outcomes (Table 2). Although our pooled estimate of effect on SL nitrate use may be clinically significant in the context of the primary trials reviewed, overall reductions in nitrate use are not always desirable. Many patients benefit from chronic therapy via oral and/or transcutaneous long-acting nitrate preparations (with nitrate-free intervals to minimize tolerance), in addition to the routine use of sublingual nitrates for acute angina episodes [55]. Like short-acting preparations, long-acting nitrates decrease cardiac workload and oxygen demand by reducing left ventricular (LV) preload and afterload. In addition, they optimize redistribution of blood flow to ischemic subendocardium by decreasing LV end diastolic pressure and dilating epicardial vessels [55].

Education about nitrates in the included trials was limited to the proper administration of SL nitrates in order to manage acute angina. This limitation points to the need to incorporate and examine the effectiveness of more comprehensive approaches to nitrate-based angina management in future psychoeducation trials; recent evidence suggests that a) patients are frequently confused and/or uninformed about the principles of short and long-acting nitrate self-administration [38].

The second outcome was self-reported HRQL, which was measured in 2 trials (Lewin et al., 2002; McGillion et al., 2006) using the disease-specific SAQ. Combined results of these trials suggested that psychoeducational interventions yield significant, small (ES = 0.26) to moderate (ES = 0.51) short-term improvements in the perception of the overall impact of heart disease on HRQL (SAQ-DP), and angina-induced physical limitations (SAQ-PL) respectively (Table 2). While these results were statistically significant, CIs were wide. In addition, the WMDs in SAQ-DP and SAQ-PL scores were 4.46 and 8.00 respectively; prior work has established that minimum 5-8 point improvements across SAQ subscales (except the SAQ-AS scale, for which larger changes are clinically meaningful) are required to reflect clinically meaningful change in disease-specific HRQL for angina patients [15,44,56,57]. Therefore, only the pooled estimate of effect on angina-induced physical limitations may be of clinical significance.

The similar samples of the 2 trials, as well as their relatively equal weighting (49.08%; 50.92%) and variance in SAQ-PL scores (Fig. 3), suggests that differences in the strength of their respective interventions may have been a key factor in their clinically sub-optimal, combined impact on physical functioning. One trial tested the effects of community group-based psychoeducation (McGillion et al. 2006), and observed greater positive short-term impact on angina-induced physical limitations than the other trial, which examined individual counseling in a clinic setting, with supportive telephone follow-up (Lewin 2002). However, discrepancy in the end-points of these studies signals caution in making such inferences about the relative strengths of their interventions. In addition, although there was clear overlap in content, the interventions in these studies were somewhat heterogeneous with respect to duration, format and process; the degree to which this heterogeneity negatively affected statistical and/or clinical significance is unclear.

With respect to disease perception, it appeared that the individual-based clinic intervention had a more uniform impact on disease perception scores (SAQ-DP) than the group-based intervention, but to a less-positive degree on average (Fig. 4). High variance in scores was therefore likely a main contributor to the observed pooled effect on disease perception, in addition to any diluting impact that intervention heterogeneity may have exerted.

Neither trial included in HRQL analyses reported significant positive effects on treatment satisfaction; not surprisingly, the pooled effect on treatment satisfaction scores (SAQ-TS) was also insignificant. Beyond variance in scores and intervention differences, statistically insignificant results for treatment satisfaction (TS) at the individual trial level were likely primarily driven by the psychometric properties of the SAQ-TS scale. This scale is comprised of 3 items oriented toward patient satisfaction with physician care [44]. Despite their differences, the interventions in both trials were delivered by nurses, not physicians, and the respective short-term end points of these trials likely did not allow sufficient time for potential improvements in patient-physician rapport.

The third outcome of this review was psychological well-being. While a number of reviews have suggested that broader psychological interventions are of clinical value for patients with heart disease, there is insufficient evidence to make recommendations since pooled estimates of the effect of psychoeducation on psychological well-being were not possible.

Overall, though the meta-analytic results of this review appear somewhat promising for the outcomes that were amenable to pooled estimates of effect, they must be interpreted with a high level of caution. Confidence intervals, for HRQL in particular, were wide. The methodological quality of the included trials ranged from good to poor. Comprehensiveness in examining baseline group differences varied, sample sizes were generally small, and trial reports often lacked detail with respect to allocation concealment, outcome assessment, reliability and validity of symptom-related measures, standardized intervention delivery, and experimental controls. Moreover, only data from selected trials could be pooled to estimate combined effects on angina symptom profile and HRQL due to the heterogeneity of a number of measures used. Finally, interventions across trials were heterogeneous with respect to duration, format (e.g. individual versus group-based) and process; intervener credentials and substantive content also varied.

Implications

Key questions about the effectiveness of psychoeducational interventions for patients with CSA remain unanswered. A common and seemingly critical element among these interventions was the provision of a variety of supports to enhance patients’ confidence and skills for angina-self-management. Yet, the ideal intervention design that would yield maximal and replicable benefit for these patients is not known. This next step is critical to developing psychoeducation as a potential mainstay of adjunctive treatment of stable angina. Major and reliable improvements in HRQOL, self-efficacy, and illness-related costs have consistently been reported in other complex chronic populations (e.g. arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, chronic non-cancer pain), once ideal intervention designs have been validated [40,58,59].

The sustainability of observed improvements in angina symptom profile and aspects of self-reported HRQL has also not been examined. A more comprehensive approach to educating participants about the principles of safe nitrate use, beyond the management of acute angina episodes, is also required. Each trial also used a single site to test their respective interventions. Therefore, individual trial results may be context-dependent and have limited generalizability. Robust multi-site trials with adequate power, standardized and replicable interventions, consistency in measurement, and longer-term follow-up are needed to avoid potential sources of bias and determine, more definitively, the effectiveness of psychoeducational interventions as an adjunctive means for improving CSA symptoms, HRQL and psychological well-being.

SUMMARY

CSA is a major clinical problem that poses considerable societal burden and deleterious impact on HRQL. While pooled trial results suggest that psychoeducational interventions may have a positive, short term impact on angina symptom frequency, SL nitrate use, and aspects of self-reported HRQL, additional well-designed trials are required to determine both the magnitude and sustainability of the effect of these interventions for CSA patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge Ms. Fang Zhung for Chinese translation, and Ms. Melanie Browne, BHSC, MLIS, Information Specialist, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Canada for external audit and replication of our search strategy.

Footnotes

Statistics Canada, Health Services Division. Unpublished vital statistics standard tables for 1996, Special tabulations. In: Health Canada: Statistical report on the health of Canadians.

Intercontinental Medical Statistics Canada. Heart Disease and stroke in Canada. In: Unpublished Data. 1995, Health Canada, Health Promotion Branch- LCDC.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr. Michael McGillion was principal investigator of one trial included in this review.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stewart S, Inglis S, Hawkes A. Chronic cardiac care: A practical guide to specialist nurse management. Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Management of stable angina pectoris. Recommendations of the Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 1997;18:394–413. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Versaci F, Gaspardone A, Tomai F, Proietti I, Crea F. Chest pain after coronary artery stent implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:500–4. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)02287-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marzilli M. Recurrent and resistant angina: Is the metabolic approach an appropriate answer? Coron Artery Dis. 2004;15(1):S23–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sirois BC, Sears SF, Bertolet B. Biomedical and psychosocial predictors of anginal frequency in patients following angioplasty with and without coronary stenting. J Behav Med. 2003;26:535–51. doi: 10.1023/a:1026201818892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brorsson B, Bernstein SJ, Brook RH, Werko L. Quality of life of chronic stable angina patients four years after coronary angioplasty or coronary artery bypass surgery. J Intern Med. 2001;249:47–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2001.00782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brorsson B, Bernstein SJ, Brook RH, Werko L. Quality of life of patients with chronic stable angina before and 4 years after coronary artery revascularization compared with a normal population. Heart. 2002;87:140–5. doi: 10.1136/heart.87.2.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caine N, Sharples LD, Wallwork J. Prospective study of health related quality of life before and after coronary artery bypass grafting: outcome at 5 years. Heart. 1999;81:347–51. doi: 10.1136/hrt.81.4.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erixson G, Jerlock M, Dahlberg K. Experiences of living with angina pectoris. Nurs Sci Res Nordic Countries. 1997;17:34–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gardner K, Chapple A. Barriers to referral in patients with angina: Qualitative study. BMJ. 1999;319:418–21. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7207.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyons RA, Lo SV, Littlepage BNC. Comparative health status of patients with 11 common illnesses in Wales. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1994;48:388–90. doi: 10.1136/jech.48.4.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacDermott AFN. Living with angina pectoris: A phenomenological study. EJCN. 2002;1:265–72. doi: 10.1016/s1474-5151(02)00047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miklaucich M. Limitations on life Women's lived experiences of angina. J Adv Nurs. 1998;28:1207–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pocock SJ, Henderson RA, Seed P, Treasure T, Hampton J. Quality of life, employment status, and anginal symptoms after coronary artery bypass surgery: 3-year follow-up in the randomized intervention treatment of angina (RITA) trial. Circulation. 1996;94:135–42. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spertus JA, Jones P, McDonell M, Fan V, Fihn SD. Health status predicts long-term outcome in outpatients with coronary disease. Circulation. 2002;106:43–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000020688.24874.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spertus JA, Salisbury AC, Jones PG, Conaway DG, Thompson RC. Predictors of quality of life benefit after percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2004;110:3789–94 . doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000150392.70749.C7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wandell PE, Brorsson B, Aberg H. Functioning and well-being of patients with type 2 diabetes or angina pectoris, compared with the general population. Diabetes Metab. 2000;26:465–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andrell P, Ekre O, Wahborg P, Eliasson T, Mannheimer C. International Association for the Study of Pain 11th World Congress on Pain [Abstract #537-P143]; 2005 Aug 21-26. Sydney, Australia: IASP Press; 2005. Quality of life in patients with refractory angina pectoris; p. 200. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lampe FC, Whincup PH, Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Walker M, Ebrahim S. The natural history of prevalent ischaemic heart disease in middle-aged men. Eur Heart J. 2000;21:1052–62. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1999.1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy NF, Stewart S, Hart CL, MacIntyre K, Hole D, McMurray JJ. A population study of the long-term consequences of Rose angina: 20-year follow-up of the Renfrew-Paisley Study. Heart. 2006;92:1739–46. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.090118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Heart Association. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2006 Update. Dallas, Texas: American Heart Association; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murphy NF, Simpson CR, MacIntyre K, McAlister FA, Chalmers J, McMurray JJV. Prevalence, incidence, primary care burden, and medical treatment of angina in Scotland: Age, sex and socioeconomic disparities: A population-based study. Heart. 2006;92:1047–54. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.069419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGillion MH, Watt-Watson J, Stevens B, LeFort S, Coyte P. Impact of psychoeducation on the cost of illness for chronic stable angina patients. Pain Res Man. 2006;12:136. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stewart S, Murphy N, Walker A, McGuire A, McMurray JJV. The current cost of angina pectoris to the National Health Service in the UK. Heart. 2003;89:848–53. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.8.848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gibbons RJ, Chatterjee K, Daley J, et al. ACC/AHA-ASIM guidelines for the management of patients with chronic stable angina: Executive summary and recommendations (A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines (Committee on Management of Patients with Chronic Stable Angina) Circulation. 1999;99:2829–48. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.21.2829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanser P, Baird M, McCans J, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society Consensus conference on the evaluation and management of chronic ischemic heart disease. Can J Cardiol. 1997;14 (Suppl C):2c–23c. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bundy C, Carroll D, Wallace L, Nagle R. Psychological treatment of chronic stable angina pectoris. Psychol Health. 1994;10:69–77. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewin B, Cay E, Todd I, et al. The angina management programme A rehabilitation treatment. Br J Cardiol. 1995:221–6. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewin RJP, Furze G, Robinson J, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a self-management plan for patients with newly diagnosed angina. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52:194–201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Payne TJ, Johnson CA, Penzein DB, et al. Chest pain self-management training for patients with coronary artery disease. J Psychosom Res. 1994;38:409–18. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)90102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gallacher JEJ, Hopkinson CA, Bennett ML, Burr ML, Elwood PC. Effect of stress management on angina. Psychol Health. 1997;12:523–32. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma W, Teng Y. Influence of cognitive and psychological intervention on negative emotion and severity of myocardial ischemia in patients with angina. Chin J Clin Rehab. 2005;24:25–7. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGillion M, Watt-Watson J, Stevens B, LeFort S, Coyte P. A psychoeducation trial for people with chronic stable angina. Circulation. 2006;114(Suppl. II):652. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barlow JH, Shaw KL, Harrison K. Consulting the ‘experts’: Children and parents' perceptions of psychoeducational interventions in the context of juvenile chronic arthritis. Health Educ Res. 1999;14:597–610. doi: 10.1093/her/14.5.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barlow J, Wright C, Sheasby J, Turner A, Hainsworth J. Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions a review. Pat Ed Couns. 2002;48:177–187. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holman H, Lorig K. Patient self-management: A key to effectiveness and efficiency in care of chronic disease. Public Health Reports. 2004;11:239–243. doi: 10.1016/j.phr.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA. 2002;288:2469–2475. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGillion MH, Watt-Watson JH, Kim J, Graham A. Learning by heart: A focused groups study to determine the psychoeducational needs of chronic stable angina patients. Can J of Cardiovasc Nurs. 2004;14:12–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holman H, Lorig K. Patients as partners in managing chronic disease. BMJ. 2000;320:526–527. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7234.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.LeFort S, Gray-Donald K, Rowat KM, Jeans ME. Randomised controlled trial of a community based psychoeducation program for the self-management of chronic pain. Pain. 1998;74:297–306. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(97)00190-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McGillion MH, Watt-Watson JH, Kim J, Yamada J. A systematic review of psychoeducational interventions for the management of chronic stable angina. J Nurs Manag. 2004;12:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2004.00472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rees K, Bennett P, West R, Smith D, Ebrahim S. Psychological interventions for coronary artery disease. Cochrance Database Syst Rev. 2007;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002902.pub2. CD002902. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hedges LV, Olkin I. Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Orlando: Academic Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spertus JA, Winder JA, Dewhurst TA, et al. Development and evaluation of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire: A new functional status measure for coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:333–41. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00397-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Potts SG, Lewin R, Fox KAA, Johnstone EC. Group psychological treatment for chest pain with normal coronary arteries. QJM. 1999;92:81–6. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/92.2.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meinart CL. Clinical trials: Design, conduct and analysis. New York: Oxford University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boutron I, Estellat C, Guittet L, et al. Methods of blinding in reports of randomized controlled trials assessing pharmacologic treatments: A systematic review. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e425. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sackett DL. Bias in analytic research. J Chronic Dis. 1979;32:51–63. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(79)90012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen H. The conceptual framework of the theory-driven perspective. Eval Program Plann. 1989;12:391–6. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Friedman LM. Fundamentals of clinical trials. St. Louis: MO: Mosby; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155–9. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cohen J. In: Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. 2nd. Hillsdale NJ, editor. Hillsdale, N.J: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lewin B. The psychological and behavioral management of angina. J Psychosom Res. 1997;43:453–62. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(97)00143-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lewin RJP. Improving the quality of life in patients with angina. Heart. 1999;82:654–5. doi: 10.1136/hrt.82.6.654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Parker JD, Parker JO. Drug Therapy nitrate therapy for stable angina pectoris. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:520–531. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802193380807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rantanen T, Guralnik J, Sakari-Rantala R, et al. Disability, physical activity, and muscle strength in older women: The women's health and aging study. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 1999;80:130–5. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spertus JA, Dewhurst TA, Dougherty CM, et al. Benefits of an “angina clinic” for patients with coronary artery disease: A demonstration of health status measures as markers of health care quality. Am Heart J. 2002;143:145–50. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.119894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lorig K, Holman HR. Arthritis self-management studies: A twelve year review. Health Ed Quart. 1993;20:17–28. doi: 10.1177/109019819302000104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kennedy AP, Nelson E, Reeeves D, et al. A randomized controlled trial to assess the effectiveness and cost of a patient oriented self-management approach to chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2004;53:1639–1645. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.034256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]