Abstract

Purpose

The rationale for intraperitoneal (IP) chemotherapy is to expose peritoneal tumors to high drug concentrations. While multiple phase III trials have established the significant survival advantage by adding IP therapy to intravenous therapy in optimally debulked ovarian cancer patients, the use of IP chemotherapy is limited by the complications associated with indwelling catheters and by the local chemotherapy-related toxicity. The present study evaluated the effects of drug carrier on the disposition and efficacy of IP paclitaxel, for identifying strategies for further development of IP treatment.

Experimental Design

Three paclitaxel formulations, i.e., Cremophor formulation, Cremophor-free paclitaxel-loaded gelatin nanoparticles and polymeric microparticles, were evaluated for peritoneal targeting advantage and antitumor activity in mice. Whole body autoradiography and scanning electron microscopy were used to visualize the spatial drug distribution in tissues. A kinetic model, depicting the multiple processes involved in the peritoneal-to-plasma transfer of paclitaxel and its carriers, was established to determine the mechanisms by which drug carrier alters the peritoneal targeting advantage.

Results

Autoradiographic results indicated that IP injection yielded much higher paclitaxel concentrations in intestinal tissues compared to intravenous injection. Compared to the Cremophor and nanoparticle formulations, the microparticles showed slower drug clearance from the peritoneal cavity, slower absorption into the systemic circulation, longer residence time in the peritoneal cavity, 5- to 22-times greater peritoneal targeting advantage and ∼2-times longer increase in survival time (p<0.01 for all parameters).

Conclusions

Our results indicate the important roles of drug carrier in determining the peritoneal targeting advantage and antitumor activity of IP treatment.

Keywords: paclitaxel, intraperitoneal therapy, carrier, microparticles

INTRODUCTION

The rationale for intraperitoneal (IP) chemotherapy is to expose tumors located in the peritoneal cavity to high drug concentrations based on spatial proximity. IP therapy has been safely administered to cancer patients and provides 20- to 1,000-fold higher peritoneal concentrations compared to plasma concentrations for cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and paclitaxel (1–3).

Several clinical studies have demonstrated the activity of IP paclitaxel and cisplatin against advanced ovarian cancer (4–10). The results of six randomized trials show that IP therapy yielded, on average, a 21.6% decrease in the risk of death and 12-month longer overall survival time (11). The 16-month survival extension by adding IP chemotherapy to intravenous chemotherapy, shown in the most recently completed phase III trial by the Gynecological Oncology Group (GOG-172), is considered the most significant advance in ovarian cancer research in the last 15 years (11, 12).

The earlier clinical trials of IP paclitaxel were conducted using the first formulation approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, where paclitaxel is solubilized in 50:50 Cremophor EL:ethanol (e.g., Taxol®, referred to as Cremophor formulation). In humans, IP paclitaxel/Cremophor is slowly cleared from the peritoneal cavity, with a 28-fold longer elimination half-life compared to 5-fluorouracil, cisplatin or doxorubicin (>72 hr vs 1–3 hr) (2, 13, 14). A more recent study evaluated the role of Cremophor on the clearance of paclitaxel in four patients given an IP dose of radiolabeled paclitaxel in tracer quantity on day 1 followed by an IP dose of the Cremophor formulation on day 4 (15). The two formulations showed different dispositions; the radiolabeled dose showed significantly higher absorption into the systemic circulation (100% vs 31%) and a shorter residence time in peritoneal fluid (7 vs 41 hr). Another study evaluated the role of formulation on the peritoneal targeting advantage of paclitaxel and docetaxel in rats; the results showed no difference in absorption rate constant in the peritoneal absorption when both taxanes were formulated in Cremophor whereas a 20-fold increase in the rate and extent of absorption was observed for docetaxel formulated in 1.5% Tween-80 (16). These differences in pharmacokinetics led to the conclusion that the entrapment of paclitaxel in Cremophor micelles extends the residence time in the peritoneal cavity. However, because the entrapment of paclitaxel in Cremophor micelles reduces the free drug fraction available to tumors (17), it is uncertain whether a longer residence of the Cremophor formulation would necessarily lead to greater antitumor activity.

Extensive efforts have been invested in developing alternative formulations of paclitaxel for intravenous administration, in part to overcome the hypersensitivity associated with Cremophor. In 2005, FDA approved a second formulation where paclitaxel is conjugated to albumin (Abraxane®), based on its superior activity in breast cancer patients who received prior chemotherapy. The higher activity of Abraxane® may be a result of its preferential distribution to tumors (18, 19); our laboratory has shown that the tissue distribution of paclitaxel, when given intravenously, is highly dependent on its carrier (20). Abraxane® has not been evaluated in IP therapy.

In spite of the demonstrated survival advantage, the use of IP chemotherapy is limited by several complications, i.e., infection due to prolonged use of indwelling catheter and local toxicity (e.g., abdominal pain, intestinal toxicity). These problems led to the inability of a majority of patients (up to nearly 60%) to complete the scheduled six weekly treatments (5, 9) and the reluctance of the medical community to use IP therapy (12).

One approach to overcome the catheter-related complications is to use sustained release drug formulations that require less frequent dosing. Early research efforts in this area have shown promising results. For example, IP administration of cisplatin encapsulated in poly(lactic acid) microparticles (100–200 µm diameter, releasing cisplatin over 4 weeks) resulted in localization of microparticles and significantly higher drug concentrations in tumors located on the omentum, compared to cisplatin solution (21). Likewise, poly(lactic-glycolic) microparticles that release 5-fluorouracil over 3 weeks yielded significantly higher drug concentrations in IP tissues (omentum, mesentery) compared to systemic tissues (blood, lungs, heart) (22).

The present study evaluated the effects of carrier on the disposition and efficacy of IP paclitaxel. We evaluated three paclitaxel formulations, i.e., Cremophor formulation, Cremophor-free paclitaxel-loaded gelatin nanoparticles (∼660 nm diameter) that rapidly released paclitaxel (90% in 2 hr), and Cremophor-free paclitaxel-loaded polymeric microparticles (4 µm diameter) that releases paclitaxel slowly (70% in 24 hr).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and reagents

Paclitaxel was purchased from Handetech (Houston, TX). Cephalomannine was obtained from the National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MD) and 3"-3H-paclitaxel (specific activity, 10.6 Ci/mmol) from the National Cancer Institute or Moravek Biochemicals, Inc. (Brea, CA). High performance liquid chromatographic (HPLC) analysis showed that paclitaxel, 3"-3H-paclitaxel, and cephalomannine were >99% pure. Poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) with intrinsic viscosity of 0.18 dl/g were purchased from Birmingham Polymers, Inc. (Birmingham, AL), cefotaxime sodium from Hoechst-Roussel (Somerville, NJ), gentamicin from Solo Park Laboratories (Franklin Park, IL), and McCoy’s culture medium from Life Technologies, Inc. (Grand Island, NY). Poly(vinyl alcohol), Type A gelatin from porcine skin, Tween-20, sodium sulfate, sodium metabisulfite, pronase, Cremophor EL and glutaraldehyde (25% in water) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). HPLC solvents were purchased from Fisher Scientific Company (Fair Lawn, NJ). All chemicals and reagents were used as received.

Overview of experiments

Two groups of studies were performed. The first group of studies aimed to visualize the spatial distribution of paclitaxel in the whole body and was investigated using autoradiography of 3H-paclitaxel. The second group evaluated the effects of carrier on (a) clearance of paclitaxel from the peritoneal cavity, (b) apparent rate and extent of absorption from the peritoneal cavity, and (c) antitumor activity. These latter studies required blood and peritoneal fluid samples and were conducted using nonradiolabeled drug and HPLC analysis of drug concentrations. All studies used the same dose of paclitaxel (equivalent to 10 mg/kg), to ensure that the data was not affected by the nonlinear pharmacokinetics of paclitaxel (23, 24).

Preparation of paclitaxel formulations

Three formulations were studied. For the Cremophor formulation, paclitaxel was dissolved in Cremophor EL:ethanol (1:1, v:v) and then diluted with sterile physiological saline to a final concentration of 1 mg/ml.

Paclitaxel-loaded gelatin nanoparticles were prepared and characterized as previously described (25). The drug content in the paclitaxel-loaded gelatin nanoparticles, determined after enzymatic digestion using a proteolytic enzyme, pronase, was 2%. The nanoparticles had an average diameter of 664 nm (range, 300 to 900 nm; median, 648 nm) and released 90% of the drug load in 2 hr under sink conditions. Gelatin nanoparticles are degraded enzymatically (25). A pilot study found that in the presence of peritoneal fluid recovered from mice (diluted 1:50 with PBS), 90% of the nanoparticles were degraded in 2 hr while less than 5% were degraded in PBS only (monitored by measuring the changes in turbidity).

Paclitaxel-loaded PLGA microparticles were prepared and characterized as described elsewhere (manuscript in preparation). Briefly, PLGA and paclitaxel powder was co-dissolved in 5 ml of methylene chloride, emulsified in 20 ml of 1% PVA solution by homogenization for 30 sec (for obtaining smaller microparticles). The emulsion was then diluted into 500 ml of 0.1% poly(vinyl alcohol) solution. After 30 min, microparticles was collected by centrifugation, washed three times with deionized water, and lyophilized. The microparticles had an average diameter, determined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), of 3.63 ± 1.68 µm (1.38–6.72 µm with 90% reference interval; median, 3.3 µm) and released 70% of the drug load within 24 hr under sink conditions.

Animal protocols

Female nude Balb/C mice (6–8 weeks old, 16–18 g body weight) were obtained from NCI/Charles River Laboratories, and housed and cared for in accordance with institutional guidelines. Mice were allowed at least 3–5 days to acclimate to the new surroundings and had access to food and water ad libitum.

Dosing solutions were administered between 8 am and 12 noon. Intravenous administration was through a tail vein. IP administration was through an angiocatheter (18-gauge, 1.3 mm; Becton-Dickinson; Sandy, UT) inserted into the peritoneal cavity. At predetermined times, mice were anethesized and blood samples were collected through the retro-orbital venous plexus. Afterward, 2 ml of physiologic saline was instilled in the peritoneal cavity through an indwelling angiocatheter and withdrawn after gently massaging the abdomen for 2–5 min. The washing procedures were repeated and the two lavage samples were pooled. Subsequently, mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. All samples, dosing solutions, and the remaining animal carcasses were stored at −70°C until analysis.

Whole-body autoradiography

Whole body autoradiography was used to study the spatial distribution of paclitaxel in peritoneal and systemic tissues in mice given an IP or intravenous dose of the Cremophor formulation (containing 10 mg/kg non-radiolabeled paclitaxel plus 1 mCi/kg 3H-paclitaxel). At predetermined times, an animal was euthanized and immediately placed in hexane cooled with dry ice using a published method (26), with the following minor modifications. The frozen carcasses were embedded in a carboxymethyl cellulose gel (Bondex International Inc., St. Louis, MO). The gel molds were again immersed in dry ice/hexane mixture at −70°C for 20 min and stored at −20°C until sectioning. Frozen whole animal coronal sections of 30–40 µm were obtained using a PMV 450 cryomicrotome (Stockholm, Sweden), kept frozen at −25°C and mounted on Scotch tape 800 (3M Co., St. Paul, MN). Multiple sections were taken from various planes, allowing for complete examination of all major organs. Sections were lyophilized at −25°C for up to 3 days, photographed, and placed together with precalibrated tritium microscale autoradiography standards against tritium-sensitive film (Hyperfilm, Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL). After exposure for 7 days at 4°C., the film was moved through the following processing tanks in succession at room temperature: (a) developer tank (Kodak D-19) for 5 min, (b) stop tank (Kodak Indicator Stop Solution; 16 ml per liter) for 30 sec, (c) acid-hardening fixing bath (Kodak F-5) for 5 min, (d) washing tank (deionized water) for 5 min, and (e) rinsing tank (Kodak Photo-Flo 200 Solution; 5.5 mL per 1.10 liter) for 30 sec, and then air-dried. A digitized image was captured using a scanner (MicroTek ScanMaker V310), and analyzed using the NIH ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image/download.html). The densitometry measurements of the tritium standards were used to generate a standard curve using least-squares regression and a second-order polynomial function. Tissues-of-interest in each tape section were then selected, digitized, and converted to relative concentrations using the standard curve.

Scanning electron microscopy of particle distribution on diaphragm

Mice were given an IP injection of paclitaxel-loaded gelatin nanoparticles or microparticles (n=2 per formulation). After 15 min, mice were euthanized and the diaphragm was excised, fixed in PBS containing 4% glutaldehyde for 2 hr, lyophilized, coated with gold and observed under SEM (Philips XL 30 SEM).

Sample analysis by HPLC

Plasma and peritoneal lavage samples were extracted and analyzed using our previously reported column-switching HPLC assay, with cephalomannine as the internal standard (27, 28). The limit of sensitivity for paclitaxel was 1 ng per injection.

Pharmacokinetic data analysis

The effects of carrier on paclitaxel absorption from the peritoneal cavity were studied by comparing the rate and extent of absorption into the systemic circulation. The systemic bioavailability of an IP dose of each of the three formulations was calculated using the pharmacokinetics of an intravenous dose of the Cremophor formulation as the reference. We did not use intravenous nanoparticles as references because the particles were not expected to reflect the drug entity absorbed from the peritoneal cavity (i.e., free drug). For peritoneal absorption, the area under the % dosetime curve (AUC) and the area under moment curve (AUMC) from 0 to 168 hr were calculated using the trapezoid rule. Apparent peritoneal absorption rate constant was calculated from the initial slope of the log-linear plot of percent of dose-time curve. For systemic absorption, the area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC) and the area under moment curve (AUMC) for nanoparticle and Cremophor formulation from 0 to 24 hr and for microparticle formulation from 0 to 96 hr were calculated using the trapezoid rule. The mean peritoneal and plasma residence time (MRT) after intraperitoneal administration was calculated as AUMC/AUC, respectively. Peritoneal targeting advantage was calculated as ratios of AUC in peritoneal cavity from 0 to 168 hr to AUC in plasma from 0 to 24 hr. Plasma samples were taken at 168 hr postdose in only a couple of animals and drug concentrations in those animals were determined to be below the limit of quantitation. The contribution of the plasma AUC from the last quantifiable time point to 168 hr based on the elimination rate is not considered to be substantial and not likely to influence the overall peritoneal targeting advantage.

Antitumor activity

The effects of carriers on the survival benefits of paclitaxel formulations were investigated. The desired human xenograft tumor model should satisfy several criteria, i.e., 100% take rate (tumor development in all animals after IP implantation with tumor cells), reproducible and relatively rapid disease establishment and progression. We evaluated two cell lines, human pancreatic Hs766T cancer cells (gift from Dr. Byoungwoo Ryu, John Hopkins Medical Institute, Baltimore, MD) and human ovarian SKOV3 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA), and successfully developed an IP Hs766T model that satisfied the above criteria, as follows.

Hs766T cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's media containing 9% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 90 µg/ml gentamicin, and 90 µg/ml cefotaxime sodium at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. IP implantation of the original cell line into female athymic nu/nu mice (20 × 106 cells in a volume of 0.5 ml) resulted in a take-rate of 30%−40% (tumors were evident after 2 weeks). Reimplantation of cells harvested from the ascites fluid in animals with established IP tumors (expanded in culture) into new recipient hosts resulted in tumor establishment in all animals and death after 40 days (n=12, median survival time was 21.5 days). Drug treatment was initiated at about 50% of the median survival time of the untreated mice (i.e., day 10 after tumor implantation). Two studies were conducted. One study compared the activity of paclitaxel in Cremophor to that of paclitaxel nanoparticles, whereas the second study compared paclitaxel in Cremophor to paclitaxel microparticles. Both studies used a paclitaxel-equivalent dose of 40 mg/kg. Additional control animals receiving only physiological saline were included in both studies to control for potential changes in survival time over the course of experimentation.

Post-mortem autopsies were performed to evaluate the cause of death. Typically, mice that died within 10 days post-treatment were considered treatment-related deaths (e.g., >15% body weight loss, internal hemorrhage due to faulty injections). Mice that died after 10 days post-treatment and presented with tumor nodules and/or tumor infiltration into organs were considered deaths due to disease progression.

Statistical Analysis

Median survival time (MST) and increase in MST were determined for each treatment group. Control groups from different studies were pooled for statistical analysis. The levels of significance in the differences in survival times were analyzed using the log-rank test using SAS (Cary, NC). The differences in peritoneal clearance and systemic absorption between the microparticle and other groups were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey post test. P values of less than 5% were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Spatial distribution of 3H-paclitaxel after intraperitoneal and intravenous injection

This was studied using the Cremophor formulation. Figure 1A shows a whole body section of a mouse. Figure 1B shows the images obtained using the microscale tritium standards. Figure 1C and 1D show the autoradiographs of animals obtained at different time points after intravenous and IP treatments. Figure 1E shows the concentration-time profiles obtained from densitometric analysis of the autoradiographs; the data represented the relative concentrations and not the absolute concentrations because the actual tissue weight could not be determined from the tape sections. Furthermore, as autoradiographs detected total radioactivity and did not distinguish the unchanged paclitaxel from its metabolites, the concentrations represented total drug concentrations.

Figure 1. Spatial and tissue distribution of intravenous and IP injections of 3H-paclitaxel solubilized in Cremophor EL/ethanol.

A mouse was given an IP or IV injection of the Cremophor formulation of paclitaxel (a mixture of radiolabeled and nonlabeled paclitaxel, equivalent to 10 mg/kg and 1 mCi/kg). (A) Whole body section of a mouse. (B) Densitometric signals of microscale tritium standards. The numbers correspond to the relative concentrations, with the highest level set at 100%. (C) Whole body autoradiographs at various time points after an intravenous dose. (D) Whole body autoradiographs after an IP dose. No radioactivity was detected in the brain following either administration route (limit of detection was 2 µg/g). (E) Relative tissue concentration-time profiles, determined by digital videodensitometry, after an intravenous (open symbols, dotted lines) or IP (closed symbols, solid lines) dose. No radioactivity was detected in the brain following either administration route. At least 3 mice were used for each time point. Mean ± S.D.

After an intravenous dose, the highly perfused systemic tissues showed the highest concentrations at early time points, as would be expected. For example, after 15 min, most of the radioactivity resided in the liver, followed by the small intestine, kidney, heart, lung, spleen, and colon. The subsequent decrease in the radioactivity in the liver coincided with the increase in the lumen of the small intestine (e.g., 1 hr), indicating a liver-to-intestine drug transfer. Similarly, a surge in radioactivity in the lumen of the large intestine at 2 hr coincided with a decrease in the small intestine, indicating the movement of radioactivity from the small intestine to the large intestine during GI transit. Within 2 hr, radioactivity in most organs and tissues, except the small and large intestines, had decreased to levels close to or indistinguishable from the background signal.

After IP administration, nearly all of the radioactivity was confined to tissues and organs in the peritoneal cavity at all times. At 15 min, the radioactivity was located primarily in the space surrounding the visceral tissues, indicating that the drug remained in the dosing solution. The intestinal tissues showed the highest radioactivity, followed by the liver, kidney and spleen, whereas the levels in the heart and lung were nearly indistinguishable from background.

Effects of carrier on paclitaxel clearance from peritoneal cavity and absorption into systemic circulation

The disposition of a drug administered by IP injection in the form of a carrier consists of multiple kinetic processes, i.e., drug release from carrier, clearance from the peritoneal cavity, absorption from the peritoneal cavity to the systemic circulation (e.g., plasma), and elimination (first pass and systemic). As shown below, many of these processes are affected by the drug carrier.

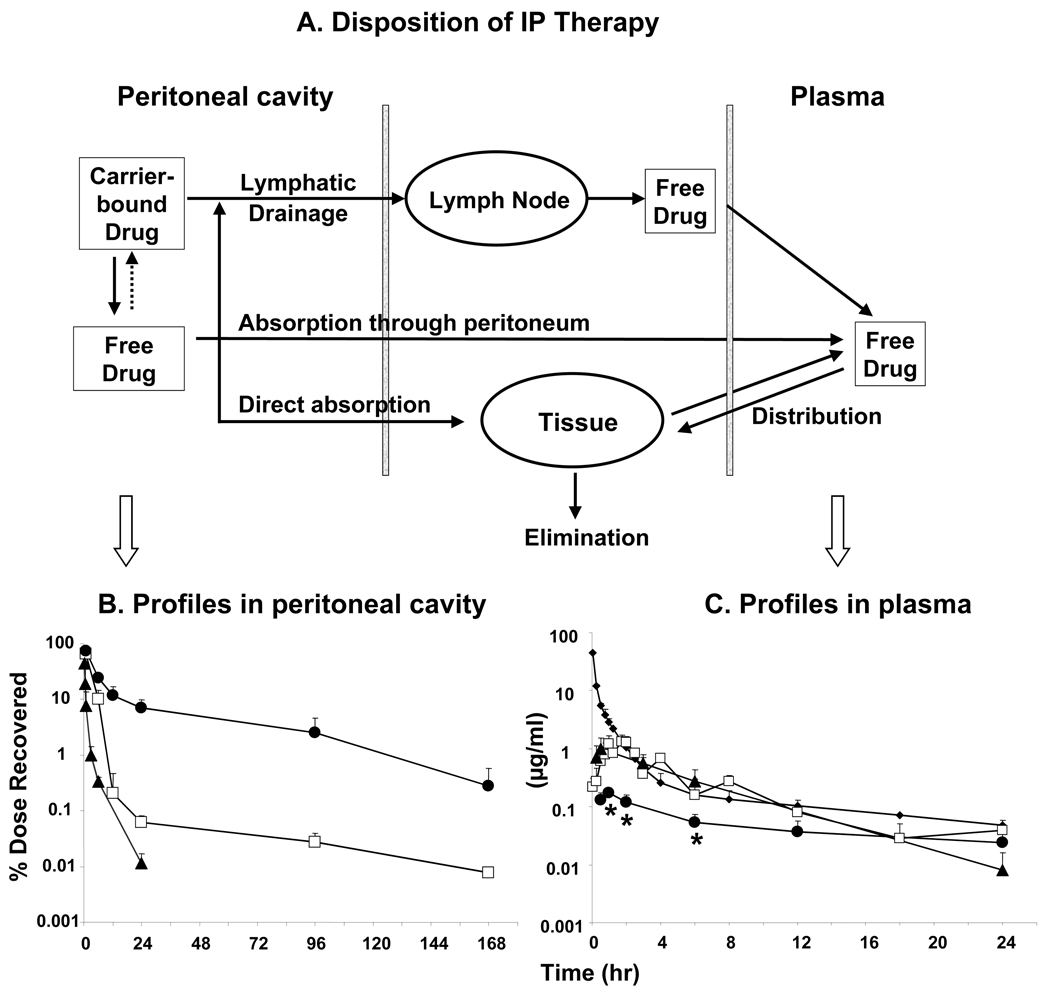

Figure 2A depicts a model describing the kinetic processes involved in drug disposition in the peritoneal cavity and systemic circulation after an IP administration of drug-loaded carriers. Based on the nature of the drug release, we proposed two separate kinetic processes for the three formulations. For the nanoparticles and microparticles, paclitaxel was incorporated into the particles through chemical manipulations. Once released, the drug would not re-enter the particles. For the Cremophor formulation, paclitaxel would be able to partition in or out of the Cremophor micelles. Micelles are formed at Cremophor concentration above 0.01% the free fraction of paclitaxel decreased from 100% in the absence of Cremophor to 23% and 11%, respectively, in 0.25% and 1% Cremophor (29). During IP therapy, the absorption of water from the cavity would increase the Cremophor concentrations to levels above its initial concentration in dosing solution (i.e., 2.5%), resulting in micelle formation. Hence, the model included a step for paclitaxel to re-enter the Cremophor micelles.

Figure 2. Effects of carrier on disposition of an IP dose of paclitaxel.

Three formulations, i.e., paclitaxel solubilized in Cremophor EL/ethanol (□), paclitaxel-loaded gelatin nanoparticles (▲), and paclitaxel-loaded polymeric microparticles (●) were administered by IP injections at 10 mg/kg. For comparison, an additional group of mice received an intravenous dose of paclitaxel solubilized in Cremophor EL/ethanol (◆). (A) A model of kinetic processes during IP treatment. Paclitaxel concentration-time profiles in plasma (B) and peritoneal lavage samples (C). Note the different time scales for panels B and C. At least 3 mice were used for each time point. Mean ± S.D. *, p<0.001, compared to other groups by one-way ANOVA with Tukey post test.

The model included two major mechanisms of clearance from the peritoneal cavity and entry into the systemic circulation, i.e., absorption through the peritoneum and drainage through the lymphatic ducts. For transport across the peritoneum, there are no known active processes; passive absorption (by diffusion or convection) through the peritoneum, a thin membrane (75 µm thick in rats (30), 90 µm thick in man (31)), is a major path for small compounds with molecular weight of less than 20 kD (32). Larger compounds or particulates are removed through the lymphatic ducts (33, 34). At the size range between 50 to 700 nm; the clearance of particulates from peritoneal cavity is independent of size (34). Within the lymphatic system, smaller particulates (<50 nm) can pass through lymph nodes while larger particulates (>500 nm) are mostly trapped in lymph nodes (34). Hence, the model assumed that only the free drug was absorbed into the systemic circulation, whereas the drug concentrations in the peritoneal lavage samples represented the sum of free drug and carrier-entrapped drug. The model also incorporated the drug distribution into peritoneal organ and tissue by direct penetration, and the firstpass organs including the liver and intestines.

Figure 2B shows the kinetics of paclitaxel in the peritoneal fluid, and Table 1 summarizes the results. The residual drug in the peritoneal cavity was recovered by peritoneal lavage. Hence only the total drug amounts in the lavage samples (instead of actual drug concentrations in the peritoneal fluid) could be accurately determined. Furthermore, the drug levels, determined using HPLC, represented the total drug comprising of free and carrier-bound drug. The peritoneal clearance of the paclitaxel delivered in Cremophor and nanoparticle formulations was rapid, resulting in <0.1% of the dose remaining after 24 hr. In comparison, the peritoneal clearance of the microparticle formulation was slower with a 40 and 75% decrease in apparent elimination rate constant, than that of the Cremophor and nanoparticle formulation, respectively. This resulted in a 17 and 700-fold higher residual peritoneal concentrations at 24 hr, 10 and 28-fold longer mean residence time in the peritoneal cavity, and 3 and 12-fold higher total peritoneal exposure with the microparticle formulation, relative to the Cremophor and nanoparticle formulation, respectively.

Table 1. Effects of carrier on peritoneal clearance and systemic absorption of IP chemotherapy.

For peritoneal absorption, the area under the % dose-time curve (AUC) and the area under moment curve (AUMC) from 0 to 168 hr were calculated using the trapezoid rule. Apparent peritoneal absorption rate constant was calculated from the initial slope of the log-linear plot of percent of dose-time curve. For systemic absorption, the area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC) and the area under moment curve (AUMC) for nanoparticle and Cremophor formulation from 0 to 24 hr and for microparticle formulation from 0 to 96 hr were calculated using the trapezoid rule. The mean peritoneal and plasma residence time (MRT) after intraperitoneal administration was calculated as AUMC/AUC, respectively. Tmax is the time when the maximal plasma concentration (Cmax) was observed. The systemic bioavailability F was calculated as the ratio of AUC of intraperitoneal treatment to AUC of intravenous Cremophor paclitaxel (the AUC of the intravenous dose was 169 µg*hr/ml). Peritoneal targeting advantage was calculated as ratios of AUC in peritoneal cavity from 0 to 168 hr to AUC in plasma from 0 to 24 hr. At least 3 mice were used for each time point. Mean ± S.D.

| Carrier | Drug release rate in vitro |

Peritoneal cavity | Plasma | Peritoneal targeting advantage |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of dose remaining at 24 hr |

AUC from 0 to 168 hr (% of dose*hr) |

Peritoneal absorption rate constant (hr-1) |

MRT (hr) |

Tmax (hr) |

Cmax (µg/ml) |

AUC from 0 to 24 hr (µg*hr/ml) |

F (%) |

MRT (hr) |

|||

| Nanoparticle | 90% in 2 hr | 0.01±0.01 | 46.7 | 0.39 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 1.00±0.55 | 6.39 | 37.7 | 8.7 | 7.31 |

| Cremophor | ∼10% steady statea | 0.06±0.02 | 179 | 0.16 | 2.8 | 1 | 0.85±0.19 | 6.15 | 36.3 | 7.2 | 29.1 |

| Microparticle | 70% in 24 hr | 7.14±2.62** | 559 | 0.10 | 28.5 | 1 | 0.17±0.04** | 3.61b | 9.7 | 14.9 | 155 |

Free fraction of paclitaxel in the presence of Cremophor micelles (29).

AUC(0–96 hr) is listed. AUC(0–24 hr) = 1.65 µg*hr/mL

p<0.01 compared to other groups (one-way ANOVA with Tukey post test).

Effects of carrier on paclitaxel absorption into systemic circulation and peritoneal targeting advantage

Figure 2C shows the plasma paclitaxel concentrationtime-profiles resulting from IP administration of the three formulations. Also shown are the results obtained from an intravenous dose of the Cremophor formulation; the calculated systemic clearance of the total paclitaxel concentrations (sum of free and Cremophor micelles-entrapped drug) was 0.59 L/hr/kg. Note that this value represents the apparent clearance and not necessarily the true clearance of the free paclitaxel. Table 1 summarizes the pertinent pharmacokinetic parameters.

The profiles for all three formulations, administered by IP injection, showed increasing plasma concentrations at early time points followed by a decline. This kinetic behavior is typical for absorption from an extravascular site. The Cremophor and nanoparticle formulations showed nearly superimposable profiles and pharmacokinetic parameters. In contrast, the microparticle formulation showed ∼5-fold decrease in peak plasma concentration and area-under-concentration-time profiles over 24 hr, compared to the other two formulations. Plasma concentrations were below the detection limit after 24 hr for the Cremophor and nanoparticle formulations and after 96 hr for the microparticle formulation.

Compared to intravenous administration of the same dose, IP administration of the Cremophor and nanoparticle formulations yielded 2 to 200-fold lower plasma concentrations at the early time points (up to 1 hr), followed by comparable concentrations at later time points.

Table 1 shows the peritoneal targeting advantage, calculated as the ratios of the area-under-concentration-time profiles in peritoneal to those in plasma, for the three formulations. The rank order was microparticles > Cremophor formulation > nanoparticles, with the respective ratios of about 155, 29 and 7. It is noted that these values represented the total of the free and carrier-entrapped drugs.

Comparison of particle size and lymphatic duct openings on diaphragm surface

Figure 3 shows the SEM results on the lymphatic duct openings (stomas) on a mouse subdiaphragm surface. The diameter of the openings ranged from 0.35 to 7.8 µm (37 samples from 4 mice), with median and mean values of 2.8 and 3.5 µm (standard deviation was 2.2 µm). Also shown are the nanoparticles and microparticles located near the openings. The nanoparticles (about 660 nm in diameter) were substantially smaller compared to the openings, whereas the microparticles approached the size of the openings.

Figure 3. SEM of openings and particles on diaphragm surface.

(A) Nanoparticles (arrows). (B) Microparticles (arrows). Note that Cremophor micelles (13 nm) would be approximately one-fifth the size of the nanoparticles.

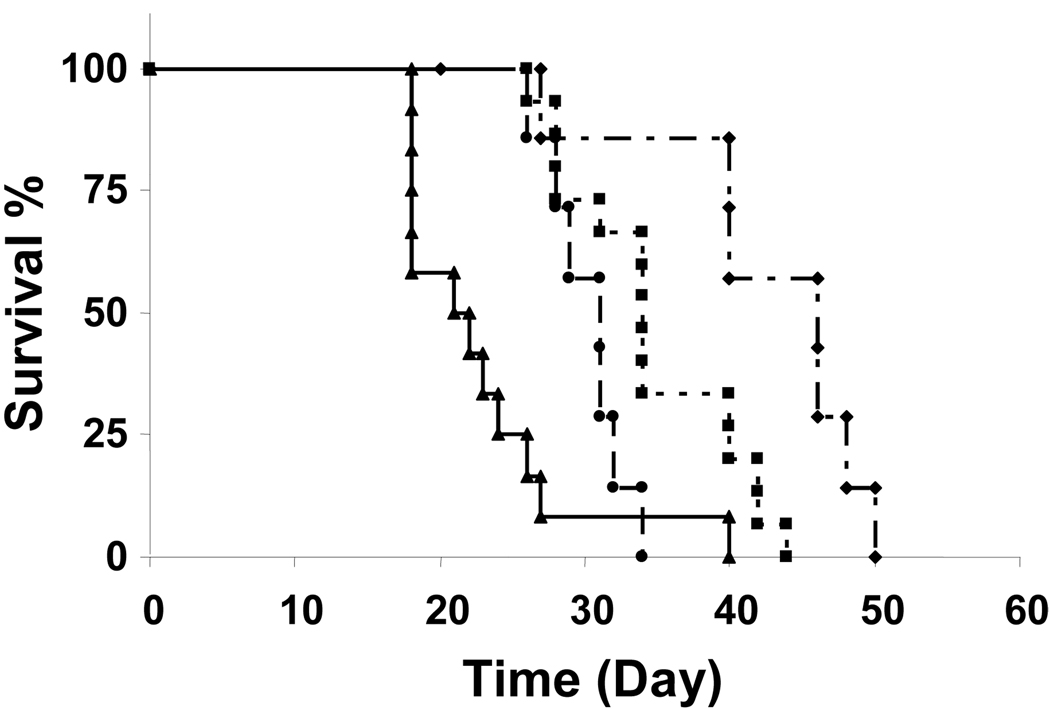

Effects of carrier on antitumor activity of paclitaxel formulations

Figure 4 shows the results. The untreated control group showed a MST of 22 days. IP treatment with the three formulations significantly prolonged the MST, in the rank order of microparticles (110% increase in MST compared to the control group) > Cremophor formulation (60% increase) > nanoparticles (40% increase). The survival extension in the microparticle group is significantly greater compared to the other two groups (p<0.01, logrank test).

Figure 4. Effects of carrier on antitumor activity of IP paclitaxel treatments.

Mice were implanted 20 × 106 Hs766T tumor cells intraperitoneally. Ten days later, mice were treated with a single IP injection of physiologic saline as control (n=12) (▲), paclitaxel in Cremophor EL/ethanol formulation (n=15) (■), paclitaxel nanoparticles (n=7) (●) and paclitaxel microparticles (n=8) (◆). The paclitaxel-equivalent dose in all drug-treated groups was 40 mg/kg. The corresponding median survival times for these groups were 22, 34, 31 and 46 days.

DISCUSSION

The present study was designed to elucidate the effects of drug carriers on the disposition and efficacy of IP chemotherapy, in order to identify approaches for improving this treatment modality.

Results of the whole body autoradiography study provided information on the spatial distribution after intravenous and IP doses of paclitaxel. An IP dose of paclitaxel yielded higher drug concentrations and longer drug retention in the peritoneal cavity and the peritoneal tissues, compared to an intravenous dose of the same formulation, thus confirming the intended peritoneal targeting by IP therapy. A comparison of the kinetics of the radioactivity in the liver and intestines after the two treatment routes further provides some insights on the potential causes of the dose-limiting toxicity of IP paclitaxel (i.e., abdominal/gastrointestinal toxicity. After an intravenous injection, paclitaxel enters the liver where it is metabolized, and the unchanged drug and metabolites undergo biliary excretion into the intestinal lumen (35). In this case, the concentrations in the liver would appear or peak before the concentrations in the intestines, as was observed. After an IP dose, using the same liver-to-intestine pathway would result in the same kinetics in liver and intestines as for the intravenous dose. This was not the case, as our data showed a more rapid drug accumulation in the intestines compared to the liver after the IP dose. Hence, our data support the alternative or additional pathway via direct drug absorption into intestinal tissues. Such absorption has been observed for small and large molecules (e.g., phenol red, insulin) directly applied to the external serosal surface of the intestinal wall (36, 37). Secondly, the data indicate more extensive drug accumulation in intestines after the IP dose. This is likely due to the smaller volume for drug distribution in the intestinal tissues/lumen, compared to the greater distribution following intravenous administration. Furthermore, bypassing the liver would avoid metabolic inactivation. These changes in drug absorption and metabolism would expose intestinal tissues to high concentrations of the unchanged drug, which would explain the significantly greater gastrointestinal toxicity of IP paclitaxel. Additional studies to evaluate the drug absorption into intestinal tissues and the pharmacodynamic relationship between drug concentration and intestinal toxicity during IP therapy are warranted.

The effects of carrier on the disposition and antitumor activity of IP paclitaxel were studied using nonradiolabeled paclitaxel delivered in three formulations, i.e., Cremophor micelles, nanoparticles and microparticles that had different rates of drug release and different particle sizes. For drug release, the rank order was nanoparticles (about 90% release in 2 hr under in vitro sink conditions) > Cremophor formulation (maintaining an equilibrium of about 10% free drug fraction until the entire drug load is released or until depletion of Cremophor micelles) > microparticles (about 70% in 24 hr under sink conditions). For particle size, the rank order was microparticles (about 4 µm diameter) > nanoparticles (about 660 nm) > Cremophor micelles (13 nm; Ref. (29)). The results demonstrated that the carrier significantly affected the residence time of paclitaxel in the peritoneal cavity, rate and extent of drug absorption from the cavity into systemic circulation, peritoneal targeting advantage, and survival advantage of the IP treatment.

The present study provided two sets of data that enabled the analysis of the effects of the physicochemical properties of drug carriers on the key processes that determine the peritoneal targeting advantage. First, the plasma concentration-time profiles provided estimates of the effects of drug release from carriers on the systemic absorption. However, the plasma profiles were the net results of three kinetic processes, i.e., drug release from carriers, absorption and metabolism of the free drug by first-pass organs such as the liver (see the kinetic model shown in Figure 2A). In comparison, the total drug concentrationtime profiles in the peritoneal cavity were not confounded by metabolism and therefore provided more definitive information on the effects of drug release rate and the carrier size on the clearance from the peritoneal cavity, as follows.

Clearance of total drug (sum of free and carrier-bound drug) from the peritoneal cavity was determined because the clearance of the free paclitaxel will remain the same irrespective of the carrier. Hence, the differences observed for the three formulations are due to differences in (a) clearance of the drug-containing carrier and (b) drug release. For drug-containing carriers, the major clearance mechanism would be the drainage through the lymphatics. As shown in Figure 3, the size of the microparticles approaches the µm-size diameters of the openings of the lymphatic ducts, which would limit its lymphatic clearance. In comparison, the smaller, nm-size Cremophor and nanoparticle formulations are easily removed by the lymphatics. Between the nm-size particles, the slower drug release from Cremophor micelles resulted in longer retention of paclitaxel in the peritoneal cavity, as compared to the nanoparticles that had a 50-times larger diameter but released the drug almost instantaneously.

With respect to the effects of drug release rate from carriers on systemic absorption, the plasma data showed that the microparticles with the slowest in vitro release rate, resulted in the lowest rate and extent of absorption in the first 24 hr. In contrast, the two formulations that released the drug load more rapidly (Cremophor and nanoparticle formulations) showed more rapid systemic absorption.

The overall result of the lower systemic absorption and higher peritoneal retention of the microparticles was the 5- to 22-fold greater peritoneal targeting advantage and ∼2-fold longer survival extension in IP tumor-bearing animals, compared to the Cremophor and nanoparticle formulations (p<0.01).

To date, there is no chemotherapeutic product specifically designed and approved for IP treatments. IP chemotherapy in patients typically uses the formulations developed for intravenous use. Our results indicate the important roles of drug carrier or formulation in determining the peritoneal targeting advantage and antitumor activity of an IP treatment. Further efforts to define the effects of drug carrier properties (e.g., size, surface charge) on intra-abdominal distribution, peritoneal retention and tumor-targeted delivery are warranted. Finally, the complex and intertwining kinetic processes that govern the drug release and removal from the peritoneal cavity, as shown in Figure 2A, suggest the additional need of engineering or computational approaches to make use of the experimental data, in order to arrive at rationally designed drug-loaded carriers that provide the maximal peritoneal targeting while eliminating the need of frequent treatments and local toxicity, thereby maximize the usefulness of IP therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in part by a research grant R37CA49816 and R43CA103133 from the National Cancer Institute, NIH, DHHS.

Abbreviations used are

- HPLC

high pressure liquid chromatography

- IP

intraperitoneal

- IV

intravenous

- MST

median survival time

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PLGA

poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide)

- SEM

scanning electron microscope

- AUC

area under curve

- MRT

mean residence time

- AUMC

area under moment curve.

REFERENCES

- 1.Markman M, Rowinsky E, Hakes T, et al. Phase I trial of intraperitoneal taxol: a Gynecoloic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:1485–1491. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.9.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Speyer JL, Collins JM, Dedrick RL, et al. Phase I and pharmacological studies of 5-fluorouracil administered intraperitoneally. Cancer Res. 1980;40:567–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimm S, Cleary SM, Lucas WE, et al. Phase I/pharmacokinetic study of intraperitoneal cisplatin and etoposide. Cancer Res. 1987;47:1712–1716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alberts DS, Liu PY, Hannigan EV, et al. Intraperitoneal cisplatin plus intravenous cyclophosphamide versus intravenous cisplatin plus intravenous cyclophosphamide for stage III ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1950–1955. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612263352603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armstrong DK, Bundy B, Wenzel L, et al. Intraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:34–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gadducci A, Carnino F, Chiara S, et al. Intraperitoneal versus intravenous cisplatin in combination with intravenous cyclophosphamide and epidoxorubicin in optimally cytoreduced advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: a randomized trial of the Gruppo Oncologico Nord-Ovest. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;76:157–162. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1999.5677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Markman M, Bundy BN, Alberts DS, et al. Phase III trial of standard-dose intravenous cisplatin plus paclitaxel versus moderately high-dose carboplatin followed by intravenous paclitaxel and intraperitoneal cisplatin in small-volume stage III ovarian carcinoma: an intergroup study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group, Southwestern Oncology Group, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1001–1007. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.4.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polyzos A, Tsavaris N, Kosmas C, et al. A comparative study of intraperitoneal carboplatin versus intravenous carboplatin with intravenous cyclophosphamide in both arms as initial chemotherapy for stage III ovarian cancer. Oncology. 1999;56:291–296. doi: 10.1159/000011980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walker JL, Armstrong DK, Huang HQ, et al. Intraperitoneal catheter outcomes in a phase III trial of intravenous versus intraperitoneal chemotherapy in optimal stage III ovarian and primary peritoneal cancer: A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;100:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yen MS, Juang CM, Lai CR, et al. Intraperitoneal cisplatin-based chemotherapy vs. intravenous cisplatin-based chemotherapy for stage III optimally cytoreduced epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001;72:55–60. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(00)00340-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. http://www.cancer.gov/newscenter/pressreleases/IPchemotherapyrelease.

- 12.Goldberg KB. Phase III Trial Shows Benefit for Old Drug, Device, for Ovarian Cancer; Will Practice Change? The Cancer Letter. 2006;32:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malviya VK, Deppe G, Boike G, Young J. Pharmacokinetics of intraperitoneal doxorubicin in combination with systemic cyclophosphamide and cis-platinum in the treatment of stage III ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1990;36:185–188. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(90)90170-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Dwyer PJ, LaCreta F, Hogan M, et al. Pharmacologic study of etoposide and cisplatin by the intraperitoneal route. J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;31:253–258. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1991.tb04971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gelderblom H, Verweij J, van Zomeren DM, et al. Influence of Cremophor El on the bioavailability of intraperitoneal paclitaxel. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1237–1241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yokogawa K, Jin M, Furui N, et al. Disposition kinetics of taxanes after intraperitoneal administration in rats and influence of surfactant vehicles. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2004;56:629–634. doi: 10.1211/0022357023303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knemeyer I, Wientjes MG, Au JL. Cremophor reduces paclitaxel penetration into bladder wall during intravesical treatment. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1999;44:241–248. doi: 10.1007/s002800050973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gradishar WJ, Tjulandin S, Davidson N, et al. Phase III trial of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel compared with polyethylated castor oil-based paclitaxel in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7794–7803. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harries M, Ellis P, Harper P. Nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel for metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7768–7771. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeh TK, Lu Z, Wientjes MG, Au JL. Formulating paclitaxel in nanoparticles alters its disposition. Pharm Res. 2005;22:867–874. doi: 10.1007/s11095-005-4581-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Natsugoe S, Tokuda K, Shimada M, et al. Morphology of the designed biodegradable cisplatin microsphere. Anticancer Res. 1999;19:5163–5167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hagiwara A, Takahashi T, Sawai K, et al. Pharmacological effects of 5-fluorouracil microspheres on peritoneal carcinomatosis in animals. Br J Cancer. 1996;74:1392–1396. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gianni L, Kearns CM, Giani A, et al. Nonlinear pharmacokinetics and metabolism of paclitaxel and its pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationships in humans. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:180–190. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.1.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kearns CM. Pharmacokinetics of the taxanes. Pharmacotherapy. 1997;17:105S–109S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu Z, Yeh TK, Tsai M, Au JL, Wientjes MG. Paclitaxel-loaded gelatin nanoparticles for intravesical bladder cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:7677–7684. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ullberg S, Larsson B. Whole-body autoradiography. Methods Enzymol. 1981;77:64–80. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(81)77012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song D, Au JLS. Isocratic high-performance liquid chromatographic assay of taxol in biological fluids and tissues using automated column switching. J Chromatogr B Biomed Appl. 1995;663:337–344. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(94)00456-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song D, Au JLS. High performance liquid chromatographic assay of taxol in biological fluids and tissues using automated column switching. J Chromatogr. 1995;663:337–344. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(94)00456-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen D, Song D, Wientjes MG, Au JL. Effect of dimethyl sulfoxide on bladder tissue penetration of intravesical paclitaxel. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:363–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duman S, Sen S, Gunal AI, et al. How can we standardize peritoneal thickness measurements in experimental studies in rats? Perit Dial Int. 2001;21 Suppl 3:S338–S341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baron MA. Structure of the intestinal peritoneum in man. Am J Anat. 1941;69:439. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flessner MF, Fenstermacher JD, Blasberg RG, Dedrick RL. Peritoneal absorption of macromolecules studied by quantitative autoradiography. Am J Physiol. 1985;248:H26–H32. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1985.248.1.H26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shih WJ, Coupal JJ, Chia HL. Communication between peritoneal cavity and mediastinal lymph nodes demonstrated by Tc-99m albumin nanocolloid intraperitoneal injection. Proc Natl Sci Counc Repub China B. 1993;17:103–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirano K, Hunt CA. Lymphatic transport of liposome-encapsulated agents: effects of liposome size following intraperitoneal administration. J Pharm Sci. 1985;74:915–921. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600740902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Monsarrat B, Alvinerie P, Wright M, et al. Hepatic metabolism and biliary excretion of Taxol in rats and humans. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1993:39–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishida K, Kuma A, Fumoto S, et al. Absorption characteristics of model compounds from the small intestinal serosal surface and a comparison with other organ surfaces. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2005;57:1073–1077. doi: 10.1211/0022357056677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waxman K, Soliman MH, Nguyen KH. Absorption of insulin in the peritoneal cavity in a diabetic animal model. Artif Organs. 1993;17:925–928. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.1993.tb00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]