Abstract

Introduction

The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) is an important regulator of lipid metabolism; it controls the differentiation of pre-adipocytes and is also found at high levels in small metastatic tumors. In this report, we describe the radiochemical synthesis and evaluation of two 18F-labeled analogs of the potent and selective PPARγ agonist, Farglitazar.

Materials and Methods

The isomeric aromatic fluorine-substituted target compounds ([18F]1 and [18F]2) were prepared in fluorine-18 labeled form, respectively, by radiofluorination of an iodonium salt precursor or by an Ullmann-type condensation with 2-iodo-4′-[18F]fluorobenzophenone after nucleophilic aromatic substitution with [18F]fluoride ion. Each compound was obtained in high specific activity and good radiochemical yield.

Results and Discussion

18F-1 and 18F-2 have high and selective PPARγ binding affinities, comparable to that of the parent molecule Farglitazar, and they were found to have good metabolic stability. Tissue biodistribution studies of 18F-1 and 18F-2 were conducted, but PPARγ-mediated uptake of both agents was minimal.

Conclusion

This study completes our first look at an important class PPARγ ligands as potential PET imaging agents for breast cancer and vascular disease. Although 18F-1 and 18F-2 have high affinity for PPARγ and good metabolic stability, their poor target-tissue distribution properties, which likely reflects their high lipophilicity combined with the low titer of PPARγ in target tissues, indicate that they have limited potential as PPARγ-PET imaging agents.

Keywords: the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, PPARγ, fluorine-18, iodonium salt, nucleophilic aromatic substitution, Ullmann coupling

1. Introduction

The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) constitute three members of the nuclear receptor superfamily, PPARα, PPARγ, and PPARδ [1, 2]. Each of these subtypes plays an important role in metabolic processes, such as lipid metabolism, glucose homeostasis, inflammation, and cell differentiation [3, 4]. The PPARγ subtype is considered to be a regulator of lipid metabolism in many tissues and specifically promotes differentiation of liposarcoma solid tumor cells [5, 6]. The antitumor activity of several PPARγ ligands has been investigated, [7, 8], and in clinical trials, troglitazone has been shown to inhibit the growth of liposarcomas in patients with advanced disease, by inducing differentiation in the tumor cells [7, 9].

PPARγ is also expressed in several human breast cancer cell lines. Recently, a number of laboratories have shown that PPARγ activation alters the growth characteristics of breast cancer cells [7, 10, 11]. Thus, it is theorized that PPARγ ligands labeled with positron-emitting radionuclides, could be used both for the in vivo assessment of lipid metabolism in disorders such as obesity, type-2 diabetes, vascular disease [12], and for the detection of certain types of tumors, breast cancer, in particular.

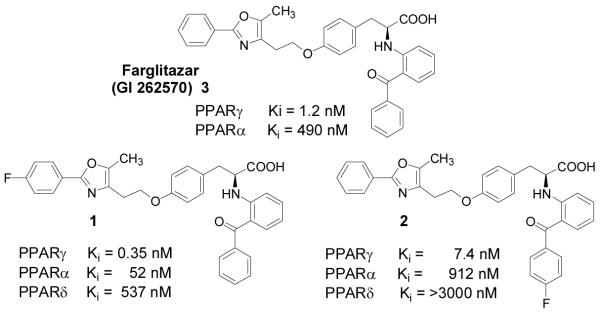

To develop agents for imaging PPARγ by positron emission tomography (PET), our group initially evaluated two fluorine-18 labeled PPARγ receptor ligands based on the known 2-alkoxy-3-phenylpropanoic acid PPARγ ligand, SB 213 068 [13]. Tissue distribution studies of these compounds, however, did not show evidence of receptor-mediated uptake in brown fat, the most receptor-rich tissue [14, 15]. Because of the poor behavior of these SB 213 068 analogs, we focused our attention on the tyrosine-benzophenone class of PPARγ regulators reported by researchers at Glaxo SmithKline (GSK) (Figure 1) [16-19]. Recently, Mathews, et al., described the preparation of a carbon-11 labeled analog of a PPARγ ligand (GW7845) as an imaging agent [20]. This compound is a tyrosine-based PPARγ ligand that is smaller and of somewhat lower affinity than the tyrosine-benzophenone PPARγ ligands. In tissue biodistribution studies, this compound did not show evidence of PPARγ-mediated uptake.

Figure1.

Farglitazar (3) and fluorine-labeled analogs (1 and 2). Binding affinities for the three PPARs were determined using competitive radiometric binding assays [22, 23].

Among the members of the novel benzophenone-tyrosine class, Farglitazar (GI 262570, 3, Figure 1) has particularly high affinity for PPARγ and shows good potency in vivo [18, 21]. We recently described the synthesis and PPARγ binding affinity of two Farglitazar analogs that are fluorine-substituted on either the distal benzene ring (the oxazole phenyl substituent) or the proximal benzene ring (part of the benzophenone group) (Figure 1) [22, 23]. The binding affinities of these two analogs of Farglitazar were 3-fold better (for 1) or 6-fold poorer (for 2) than that of the parent ligand, respectively [22, 23].

To label the distal phenyl (18F-1), we synthesized various iodonium salt precursors using Koser’s reagents [22, 24-27], which allowed fluorine incorporation simply by warming these salts with fluoride ion. To label the proximal ring (18F-2), we prepared a trimethylammonium benzophenone precursor that could be readily labeled at the para position with fluoride ion, and subsequently coupled to the tyrosine core of the ligand by a rapid Ullmann-type amine arylation reaction [23, 28-30]. In this report, we describe details of the radiofluorination of these two PPARγ ligands, their metabolic stability, and their in vivo tissue biodistribution in rats.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 General Methods

Unless otherwise stated, all chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. and used without further purification. Unlabeled compounds and precursors were synthesized in our laboratory following published reports [22, 23]. H218O was purchased from Rotem Industries. Screw-cap test tubes used for fluoride incorporation were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pyrex no. 9825). Oasis HLB-6cc cartridges, 500 mg, were purchased from Waters Corp. (part no. 186000115). Vacutainer tubes (5 mL) were obtained from Becton-Dickinson (part no. 366434). 18F-Fluoride was produced at Washington University by the 18O(p,n)18F reaction through proton irradiation of 95% enriched 18O-water, using either the JSW BC16/8 cyclotron (The Japan Steel Works Ltd.) or the CS15 cyclotron (The Cyclotron Corp.). Microwave reactions were performed using a custom-designed microwave cavity, model 420BX (Micro-Now Instruments, Skokie, IL). Radiochemical purification of 18F-1 utilized a semi-preparative HPLC normal phase silica gel column (Alltech, Alltima Silica, 250 × 10 mm, 10 μm). For quality control, the radiochemical purity of 18F-1 was assayed by analytical HPLC (Alltech, Econosil C-18 column, 250 × 4.6 mm, 10 μm). The mobile phase was ammonium formate buffer/acetonitrile.

Radiochemical purification of 18F-2 utilized a semi-preparative HPLC reversed-phase C-18 column (Alltech Alltima C-18 column, 10 × 250 mm). The radiochemical purity was analyzed by analytical HPLC (Phenomenex Luna C18 column, 4.6 × 150 mm). The mobile phase was ammonium formate buffer/acetonitrile. The eluant was monitored with a variable-wavelength detector set at 254 nm for both 18F-1 and 18F-2. The radiochemical purity of the product was also checked by radio-thin-layer chromatography (radio-TLC). The TLC plates were analyzed using a Bioscan Inc., System 200 imaging scanner. Radioactivity was determined with a dose calibrator. Radiochemical yields are decay corrected to the beginning of synthesis time (BOS).

Rodents for the biodistribution studies were obtained from Charles River Laboratories and were housed in a barrier facility with a corncob-bedding that was changed twice a week. Animal handling techniques have been described previously [31].

2.2 (2S)-(2-Benzoylphenylamino)-3-(4-(2-[2-(4-[18F]fluorophenyl)-5-methyloxazol-4-yl]ethoxy)-phenyl)propionic acid (18F-1)

To a 10-mL Pyrex brand tube was added 0.5 M Cs2CO3 (16 μL) and 3.7 GBq (100 mCi) of [18F]fluoride in water. Water was azeotropically evaporated from this mixture using HPLC-grade acetonitrile (3 × 0.5 mL) in an oil bath at 110 °C under a gentle stream of nitrogen. After the final drying sequence, a solution consisting of DMF (500 μL), H2O (10 μL) and the iodonium salt 4a (2 mg) were added to the residue. The tube was capped firmly, and the contents of the tube were heated at 130 °C for 10 min. After cooling, 0.5 M LiOH (50 μL) was added to the mixture, which was then heated at 80 °C for 10 min. After the reaction tube had cooled, the mixture was diluted with 0.2 N HCl (0.5 mL) and ethyl acetate (1 mL). After being shaken, the organic layer was transferred to a 10-mL tube using a pipette. A second ethyl acetate (1 mL) extract was collected, and the combined extracts were dried with anhydrous Na2SO4 (500 μg) and concentrated under a gentle stream of nitrogen. The residue was dissolved in 1 mL of the solvent mixture consisting of 95% methylene chloride/5% isopropanol/0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. This was combined with hexane (2 mL) and injected onto the semi-preparative HPLC system (73% hexane/26% methylene chloride/1.4% isopropanol/0.03% trifluoroacetic acid, 3 mL/min) to obtain 0.74 GBq (20.0 mCi) of final product 18F-1, which eluted at 24.0 min (35%, decay corrected, 90 min). 18F-1 was identified by co-injection with an authentic sample on analytical HPLC. The HPLC fractions were combined and concentrated under a stream of nitrogen. The product was then dissolved with acetonitrile (300 μL) and H2O (2.7 mL) and loaded onto a preactivated C18 Sep-Pak. The cartridge was rinsed with additional water (5 mL) before the radiolabeled product was eluted with ethanol (0.7 mL). The product (18F-1) in ethanol was diluted with isotonic saline to give a 15% EtOH/85% saline solution. Radiochemical purity was >99%, and the specific activity after decay correction was approximately 37 GBq/μmol (1,000 Ci/mmol).

2.3 (2S)-[2-(4-Fluorobenzoyl)phenylamino]-3-(4-[2-(5-methyl-2-phenyloxazol-4-yl)ethoxy]-phenyl)propionic acid (18F-2)

18F-Fluoride, 4.1 GBq (112 mCi), was added to a test tube fitted with a screw top lid containing Kryptofix 2.2.2 (6.2 mg) and K2CO3 (1.5 mg). Water was azeotropically evaporated with an oil bath at 110 °C using wet acetonitrile (3 × 0.5 mL) under a stream of nitrogen. After the final drying sequence, the benzophenone triflate salt (5, 2.0 mg) was dissolved in dry acetonitrile (0.5 mL) and added to the 18F mixture. The tube was capped firmly, and the contents were briefly mixed before being subjected to heating at 110 °C for 10 min. After the tube was cooled, the resulting dark mixture was diluted with water (30 mL) and passed over an activated C18 Sep-Pak and washed with additional water (10 mL) and flushed with air until dry. The fluorinated benzophenone intermediate (18F-6) was eluted with pentane (3 mL), and the solvent was dried with anhydrous Na2SO4 (500 μg). The solvent was separated from the sulfate salt and removed under a stream of nitrogen to produce the dry intermediate 18F-6, 2.4 GBq (64.0 mCi). Meanwhile, in a separate container, the tyrosine derivative 7 (7.1 mg), Cs2CO3 (5.2 mg) and potassium tert-butoxide (3.2 mg) were dissolved in dry DMF (500 μL) and allowed to react at room temperature for 5 min. CuI (2.1 mg) was added to the vessel containing the fluorinated intermediate 18F-6 and was followed by addition of the tyrosine precursor 7 mixture prepared above. The resulting solution was capped and stirred at 118 °C for 90 min. The resulting green solution was diluted with a mixture of 1:1 0.3% ammonium formate/acetonitrile (2.5 mL) and injected through a Teflon filter onto a reversed-phase HPLC column (55% acetonitrile/45% 0.3% ammonium formate, 4.0 mL/min) to obtain 131 MBq (3.54 mCi) of final product 18F-2, which eluted at 15.01 min (9.3%, decay corrected, 183 min). 18F-2 was identified by co-injection with an authentic sample on HPLC. The HPLC fractions were combined and diluted with water (50 mL) and passed over an activated C18 Sep-Pak as previously described. The product 18F-2 was eluted with EtOH (1 mL), and an aliquot (1.50 MBq, 404 μCi) was taken and diluted with saline (3 mL). The resulting solution was taken up into 21 fractions for biodistribution. Radiochemical purity was >99%, and the specific activity after decay correction was approximately 19.4 GBq/μmol (540 Ci/mmol).

2.4 In vitro and in vivo stability studies

An aliquot 1.86 MBq (50 μCi) of radiolabeled compound 18F-1 in 15% ethanol-saline was added to the tube of heparinized rat blood (0.5 mL). The resulting mixture was allowed to stand at room temperature. At various time points (10, 40 and 120 min), an aliquot of blood (100 μL) was taken for analysis using radiometric normal-phase thin-layer chromatography. 18F-1 Rf = 0.23 in 9:1 EtOAc/MeOH. 18F-2 Rf = 0.16 in 9:1 EtOAc/ MeOH. TLC analysis demonstrated only intact 18F-1 up to the final time point at 120 min.

Blood samples (1 mL) were taken from one rat of each time point in the biodistribution study of 18F-2, and the amount of intact 18F-2 was followed using radiometric normal-phase thin-layer chromatography (95% EtOAc/5%MeOH). Blood analysis showed that at both the 1 hr and 2 hr time points the only detectable source of activity was due to intact 18F-2.

2.5 Animal biodistribution studies

In the following experiments, animals were handled in accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Research Animals established by the Animal Studies Committee at Washington University, School of Medicine. A complete description of the animal handling procedure, including animal care, anesthesia and monitoring, can be found in Ref [31]. After tracer administration, the animals were allowed to wake up and maintain normal husbandry until euthanasia by cervical dislocation.

In both biodistribution studies, purified (18F-1) or (18F-2) was reconstituted in 15% ethanol-saline and injected (intravenous via tail vein) into mature female Sprague-Dawley rats (200 g). Doses of radiotracer employed for 18F-1 were 25 μCi/animal (0.93 MBq) and for 18F-2 were 0.74 MBq (20 μCi/animal). Animals were sacrificed at 1 and 2 h post injection. To determine whether uptake was mediated by a high affinity, limited capacity system, one set of animals was co-injected with the radiotracer together with a blocking dose of Farglitazar (15 μg) for 18F-1 or Rosiglitazone (15 μg) for 18F-2. (Farglitazar and Rosiglitazone are comparable high affinity ligands for the PPARγ receptor and thus should be equally effective as blocking agents.) At each time point, groups of five animals each were killed, tissues of interest were removed, weighed, washed with saline, blotted dry and the radioactivity was counted. Brown fat was removed from between the shoulder blades, and white fat was sampled from alongside the kidneys. Brown fat differs from white fat in appearance, having a slightly darker color and a more solid and lumpy consistency. The injected dose (ID) was calculated by comparison with dose standards prepared from the injected solution of appropriate counting rates, and the data were expressed as percentage ID per gram of tissue (%ID/g).

3. Results and discussion

3.1 Chemistry

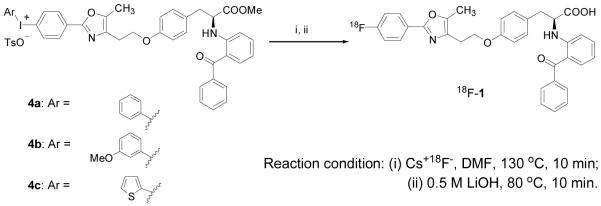

Various conditions were explored for the preparation of the PPARγ ligand 18F-1 from each of the three diaryliodonium salt precursors 4a-c whose preparation we have previously described (Scheme 1> and Table 1) [22]. When precursor (4a or 4c, 5 mg scale) was reacted with cesium [18F]fluoride or potassium [18F]fluoride Kryptofix 2.2.2 under general anhydrous radiofluorination conditions, the yield of desired product was low (Table 1, Entries 3, 7, and 8). Microwave heating failed to improve yields (Table 1, Entries 1, 2, and 6). Considering that these low radiochemical yields might be due to the limited solubility of the [18F]fluoride salts in the solvent, we added some water (10 μL) to the solvent (500 μL) and found that yields were significantly increased (Table 1, Entries 4, 9, and 10). In this aqueous environment, microwave irradiation for 90 seconds gave the desired product in 42% yield, but continued heating for 225 seconds reduced yields (Table 1, Entries 12 and 13). On the 2-mg scale in DMF, we obtained higher product yields from aryliodonium salt 4a than 4c (Table 1, Entry 4 vs. 15). Increasing the volume of water did not improve yields (Table 1, Entry 18 vs. 19). While reasonable to good radiochemical yields were obtained with the iodonium salts 4a and 4c, we were unable to obtain radiolabeled product from the thiophene-based iodonium salt precursor 4b, even though we had found that this precursor worked quite well to produce the unlabeled fluoroproduct [22].

Scheme 1.

Radiosynthesis of 18F-1 by Fluorination of Iodonium Salts

Table 1.

The Reaction of Radio-Fluorination with Iodonium Tosylates and Hydrolysis

| Entry | Precursor | [18F]F−X+ | MW or Temperature | H2Oa | Solvent | Yieldb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4a (5 mg) | [18F]F−Cs+ | MW for 225 seconds | - | DMF | 1.5% |

| 2 | [18F]F−Cs+ | MW for 315 seconds | - | DMF | 1.6% | |

| 3 | [18F]F−Cs+ | 130 °C for 10 min | - | DMF | trace | |

| 4 | 4a (2 mg) | [18F]F−Cs+ | 130 °C for 10 min | + | DMF | 35%c |

| 5 | 4b (2 mg) | [18F]F−Cs+ | 130 °C for 10 min | + | DMF | N.Pd |

| 6 | 4c (5 mg) | [18F]F− | M.W for 225 seconds | - | DMF | N.Pd |

| K+Kryptofix | ||||||

| 7 | [18F]F− | 130 °C for 15 min | - | DMF | 3.2% | |

| K+Kryptofix | ||||||

| 8 | [18F]F− | 80 °C for 10 min | - | DMF | 5.8% | |

| K+Kryptofix | ||||||

| 9 | [18F]F−Cs+ | 80 °C for 10 min | + | MeCN | 1% | |

| 10 | [18F]F−Cs+ | 130 °C for 10 min | + | MeCN | 23% | |

| 11 | [18F]F−Cs+ | 130 °C for 10 min | + | DMF | 9%c | |

| 12 | [18F]F−Cs+ | MW for 90 seconds | + | MeCN | 42% | |

| 13 | [18F]F−Cs+ | MW for 225 seconds | + | MeCN | 35% | |

| 14 | 4c (2mg) | [18F]F− | 130 °C for 10 min | + | DMF | 1% |

| K+Kryptofix | ||||||

| 15 | [18F]F−Cs+ | 130 °C for 10 min | + | DMF | 6.4% | |

| 16 | [18F]F−Cs+ | 130 °C for 10 min | + | MeCN | 4% | |

| 17 | [18F]F−Cs+ | MW for 90 seconds | + | DMF | 1% | |

| 18 | [18F]F−Cs+ | MW for 90 seconds | + | MeCN | 27%c | |

| 19 | [18F]F−Cs+ | MW for 90 seconds | +f | MeCN | 19% |

Reaction solvent (MeCN or DMF, 500 μL) was used with H2O (10 μL) or without H2O.

Progress of the reaction and yields were analyzed by radio-TLC (developing solvent: methanol/ethylacetate = 90:10 (v/v).

Yield of isolated pure product 18F-1 by semipreparative column using HPLC (70% hexane: 28% methylene chloride: 1.5% isopropanol: 0.03% trifluoroacetic acid, 254 nm, 3.5 mL/min).

No product.

Water (20 μL) was added in MeCN (500 μL).

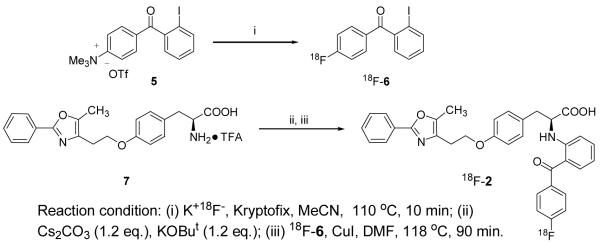

The PPARγ ligand 18F-2 was synthesized in two steps, according to an approach we described previously [23]. The first intermediate, 2-iodo-4′-fluorobenzophenone 18F-6, was obtained in very high radiochemical yields (>97%) by nucleophilic aromatic substitution of [18F]fluoride ion on the corresponding trimethylammonium salt 5. Our attempts to obtain 18F-2 directly by effecting the Ullmann condensation of compound 7 with 18F-6 in acetonitrile without purification were unsuccessful. Therefore, prior to the Ullmann coupling, we removed the inorganic salts from the crude reaction product by passage over a C18 Sep-Pak. Additionally, in reactions with unlabeled fluoride ion (Table 2, Entries 1-7), we found that the combination of the bases Cs2CO3 and potassium tert-butoxide, instead of K2CO3, always gave higher yields of product. It is noteworthy that the ratio of reaction components affects the yield of the product; the optimal ratio for compound 6 and the bases to the phenyloxazole-tyrosine TFA salt 7 is 3 to 1. Interestingly, the combination of the bases Cs2CO3 and KOBut was also critical for the success of the reaction; using Cs2 CO3 or KOBu alone led to decreased product yields (Table 2, Entries 4 and 5).

Table 2.

Optimization of Ullmann-Type C-N Coupling and Radiofluorination of 18F-2 a

| Entry | Compd 6 (eq.)b | Base(s) (eq.)b | CuI (eq.)b | Yieldsc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Cs2CO3/KOBut(3/3) | 0.5 | 10% |

| 2 | 3 | Cs2CO3/KOBut(3/3) | 0.5 | 45% |

| 3 | 3 | Cs2CO3/KOBut(3/5) | 0.5 | 15% |

| 4 | 3 | Cs2CO3 only (3) | 0.5 | trace |

| 5 | 3 | KOBut only (3) | 0.5 | 15% |

| 6 | 0.2 | Cs2CO3/KOBut(3/3) | 0.5 | 10% |

| 7 | 0.2 | Cs2CO3/KOBut | 1 | 22% |

| (1.2/1.2) | ||||

| 8d | 18F-6 | Cs2CO3/KOBut | 1 | 10%e |

| (1.2/1.2) |

Unless otherwise noted, all reactions were carried out as follows: To a dried flask with trifluoroacetate salt 7 (7.1 mg), an appropriate amount of Cs2CO3 and tert-butoxide was added acetonitrile (0.5 mL). The resulting solution was allowed to react at room temperature for 5-10 min, then unlabeled compound 6 and CuI were added, and the resulting mixture was heated at 115-118 °C for 90 min.

eq. = equivalents relative to the trifluoroacetate salt 7.

Yield of isolated pure product.

18F-6 was used and the ratio to 7 was not calculated.

Yield of pure product 18F-2 isolated by semi-preparative HPLC.

In order to radiolabel 18F-2, we modified the reaction conditions accordingly, and found that the system with reduced amount of bases (3 to 1.2 equiv) and an increased amount of CuI (0.5 to 1 equiv) is preferred (Table 2, Entry 7). The radiosynthesis of 18F-2 was conducted according to the reaction conditions optimized above, and the product was obtained in 10 ± 3% (n=3) yield (Table 2, Entry 8).

3.2 Tissue biodistribution studies

Purified 18F-1 or 18F-2 was reconstituted in 15% EtOH-saline and injected into mature female Sprague-Dawley rats via tail vein. Doses of 18F-1 employed were 25 μCi/animal and doses of 18F-2 were 20 μCi/animal. Animals were sacrificed at 1 and 2 h post injection. To determine PPARγ receptor uptake was mediated by a high-affinity limited-capacity system, one set of animals in each experiment was coinjected with the radiotracer, together with a blocking dose of Farglitazar for 18F-1 or Rosiglitazone for 18F-2. The results of these tissue biodistribution experiments are shown in Tables 3 and 4.

TABLE 3. Tissue distribution of activity of 18F-1.

| Mean percent injected dose per gram ± SD (n = 5) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue/organ | 1 h | 1 h (blocked)a | 2 h | 2 h (blocked)a |

| Blood | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.01 |

| Lung | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 0.04 ± 0.01 |

| Liver | 11.52 ± 3.80 | 8.36 ± 2.21 | 6.28 ± 1.89 | 5.51 ± 1.91 |

| Spleen | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 0.07 ± 0.03 | 0.10 ± 0.04 |

| Kidney | 0.17 ± 0.05 | 0.14 ± 0.03 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.08 ± 0.02 |

| Muscle | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.01 ± 0.00 |

| White Fat | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.01 ± 0.00 |

| Brown Fat | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.08 ± 0.01 |

| Heart | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.01 |

| Bone | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.03 ± 0.01 |

Animals were cotreated with 15 μg of Farglitazar to block PPARγ mediated uptake.

TABLE 4. Tissue distribution of activity of 18F-2.

| Mean percent injected dose per gram ± SD (n = 5) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue/organ | 1 h | 1 h (blocked)a | 2 h | 2 h (blocked)a |

| Blood | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.03 |

| Lung | 0.37 ± 0.03 | 0.38 ± 0.04 | 0.30 ± 0.02 | 0.32 ± 0.07 |

| Liver | 0.75 ± 0.1 | 0.81 ± 0.08 | 0.62 ± 0.06 | 0.65 ± 0.1 |

| Spleen | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 0.20 ± 0.04 |

| Kidney | 0.62 ± 0.1 | 0.58 ± 0.05 | 0.47 ± 0.08 | 0.54 ± 0.1 |

| Muscle | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 0.27 ± 0.01 | 0.23 ± 0.03 |

| White Fat | 1.8 ± 0.9 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.5 |

| Brown Fat | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.3 |

| Heart | 0.38 ± 0.05 | 0.36 ± 0.02 | 0.31 ± 0.01 | 0.34 ± 0.07 |

| Bone | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 0.22 ± 0.04 |

Animals were cotreated with 15 μg of Rosiglitazone to block PPARγ mediated uptake. It is not believed that the absence of selective uptake is due to metabolic

The tissue distribution studies showed that there is little selective uptake of either 18F-1 or 18F-2 in brown or white fat, principal target tissues for PPARγ [14, 15] compared to non-target tissues. Compound 18F-1 does show some decrease in brown fat with administration of a blocking dose of Farglitazar, but the specific uptake of 18F-1 in brown fat vs. non-target tissues (blood) is too low for this compound to be a practical PET agent imaging. In contrast, 18F-2 does have high levels of uptake into brown fat; however, the absence of block upon administration of Rosiglitazone implies that the tissue activity incorporation is not receptor specific. These results are similar to those reported by Mathews, et al.: no decrease in target tissue uptake upon administration of a blocking dose and low levels of specific incorporation into target tissues [20].

There are some notable differences in the overall biodistribution of the two compounds in other tissues: The higher affinity compound, 18F-1 (Cf. Figure 1), shows higher liver uptake than the lower affinity isomer, 18F-2, but overall lower uptake in other tissues. High liver uptake was also noted in the studies by Mathews [20], but it is not apparent why there would be such a difference in liver uptake of the two isomeric compounds we have studied. The PPARγ binding affinities of our two compounds differ by a factor of 20, but it is the lower affinity compound (2) that, aside from liver, has the greater overall tissue uptake. conversions of the compounds because metabolic stability studies (see Methods) and low levels of fluoride incorporation into bone implied that the injected compounds remained largely intact throughout the course of the experiment. More likely, the high lipophilicity of these compounds together with the generally low level of PPARγ expression even in the best target tissues makes it challenging to obtain the high, selective target tissue uptake as would be needed for effective PET imaging of this receptor.

4. Conclusions

An efficient method was developed for the radiosynthesis of PPARγ selective ligands 18F-1 and 18F-2, potential PET imaging agents for the development of vascular disease and breast cancer. Both 18F-1 and 18F-2 are ligands with high affinity for PPARγ and good selectivity over PPARα and PPARδ. The radiosynthesis 18F-1 was accomplished with a yield of 35%, and the radiosynthesis of 18F-2 proceeded in a yield of 10%. The labeled products were purified by HPLC and obtained in good radiochemical yields in approximately 90 min and 180 min, respectively, and the fluorine label in both 18F-1 and 18F-2 proved to be metabolically stable. Tissue distribution studies, however, showed that target tissue uptake levels were low and non-specific. Thus, in humans, these compounds are likely to be unsuitable for effective imaging of breast cancer or vascular disease.

Scheme 2.

Radiosynthesis of 18F-2 by Aromatic Fluorination and Ullmann-Type Condensation

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for support of this work by grants from the Department of Energy (FG02 86ER60401 to J.A.K.) and the National Institutes of Health (R37 CA60401 to J.A.K. and P01 HL13851 to M.J.W.).

References

- [1].Greene ME, Blumberg B, McBride OW, et al. Isolation of the human peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma cDNA: expression in hematopoietic cells and chromosomal mapping. Gene Expr. 1995;4:281–99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Issemann I, Green S. Activation of a member of the steroid hormone receptor superfamily by peroxisome proliferators. Nature. 1990;347:645–50. doi: 10.1038/347645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lemberger T, Desvergne B, Wahli W. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: a nuclear receptor signaling pathway in lipid physiology. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1996;12:335–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Willson TM, Cobb JE, Cowan DJ, et al. The Structure-Activity Relationship between Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor g Agonism and the Anti-Hyperglycemic Activity of Thiazolidinediones. J. Med. Chem. 1996;39:665–8. doi: 10.1021/jm950395a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kliewer SA, Lenhard JM, Willson TM, et al. A prostaglandin J2 metabolite binds peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor g and promotes adipocyte differentiation. Cell. 1995;83:813–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Mueller E, Smith M, Sarraf P, et al. Effects of ligand activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor g in human prostate cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:10990–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.180329197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Burstein HJ, Demetri GD, Mueller E, et al. Use of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) g ligand troglitazone as treatment for refractory breast cancer: A Phase II Study. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2003;79:391–7. doi: 10.1023/a:1024038127156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Panigrahy D, Shen LQ, Kieran MW, et al. Therapeutic potential of thiazolidinediones as anticancer agents. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2003;12:1925–37. doi: 10.1517/13543784.12.12.1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Demetri GD, Fletcher CD, Mueller E, et al. Induction of solid tumor differentiation by the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma ligand troglitazone in patients with liposarcoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:3951–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mueller E, Sarraf P, Tontonoz P, et al. Terminal differentiation of human breast cancer through PPARg. Mol. Cell. 1998;1:465–70. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wang X, Southard RC, Kilgore MW. The increased expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-g1 in human breast cancer is mediated by selective promoter usage. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5592–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Berger JP, Akiyama TE, Meinke PT. PPARs: therapeutic targets for metabolic disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2005;26:244–51. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kim S-H, Jonson SD, Welch MJ, et al. Fluorine-Substituted Ligands for the Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma (PPARg): Potential Imaging Agents for Metastatic Tumors. Bioconjugate Chem. 2001;12:439–50. doi: 10.1021/bc000153b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lowell BB, Spiegelman BM. Towards a molecular understanding of adaptive thermogenesis. Nature. 2000;404:652–60. doi: 10.1038/35007527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bookout AL, Jeong Y, Downes M, et al. Nuc Recep Signal Atlas. 2005 www.nursa.org/10.1621/datasets.02001.

- [16].Cobb JE, Blanchard SG, Boswell EG, et al. N-(2-Benzoylphenyl)-L-tyrosine PPARgamma agonists. 3. Structure-activity relationship and optimization of the N-aryl substituent. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:5055–69. doi: 10.1021/jm980414r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Collins JL, Blanchard SG, Boswell GE, et al. N-(2-Benzoylphenyl)-L-tyrosine PPARg Agonists. 2. Structure-Activity Relationship and Optimization of the Phenyl Alkyl Ether Moiety. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:5037–54. doi: 10.1021/jm980413z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Henke BR, Blanchard SG, Brackeen MF, et al. N-(2-Benzoylphenyl)-L-tyrosine PPARg Agonists. 1. Discovery of a Novel Series of Potent Antihyperglycemic and Antihyperlipidemic Agents. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:5020–36. doi: 10.1021/jm9804127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Willson TM, Brown PJ, Sternbach DD, et al. The PPARs: From orphan receptors to drug discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2000;43:527–50. doi: 10.1021/jm990554g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Mathews WB, Foss CA, Stoermer D, et al. Synthesis and biodistribution of (11)C-GW7845, a positron-emitting agonist for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-{gamma} J. Nucl. Med. 2005;46:1719–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Young PW, Buckle DR, Cantello BCC, et al. Identification of high-affinity binding sites for the insulin sensitizer rosiglitazone (BRL-49653) in rodent and human adipocytes using a radioiodinated ligand for peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor g. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998;284:751–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lee BC, Lee KC, Lee H, et al. Strategies for the labeling of halogen-substituted peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma ligands: potential positron emission tomography and single photon emission computed tomography imaging agents. Bioconjug. Chem. 2007;18:514–23. doi: 10.1021/bc060191g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lee BC, Lee KC, Lee H, et al. Synthesis and binding affinity of a fluorine-substituted peroxisome proliferator-activated gamma (PPARgamma) ligand as a potential positron emission tomography (PET) imaging agent. Bioconjug. Chem. 2007;18:507–13. doi: 10.1021/bc060190o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Koser GF, Wettach RH, Smith CS. New methodology in iodonium salt synthesis. Reactions of [hydroxy(tosyloxy)iodo]arenes with aryltrimethylsilanes. J. Org. Chem. 1980;45:1543–4. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Pike VW, Butt F, Shah A, et al. Facile synthesis of substituted diaryliodonium tosylates by treatment of aryltributylstannanes with Koser’s reagent. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1999:245–8. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Shah A, Pike VW, Widdowson DA. Synthesis of [18F]fluoroarenes from the reaction of cyclotron-produced [18F]fluoride ion with diaryliodonium salts. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1998:2043–6. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Van der Puy M. Conversion of diaryliodonium salts to aryl fluorides. J. Fluorine Chem. 1982;21:385–92. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Clement J-B, Hayes JF, Sheldrake HM, et al. Synthesis of SB-214857 using copper catalyzed amination of aryl bromides with L-aspartic acid. Synlett. 2001:1423–7. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ma D, Zhang Y, Yao J, et al. Accelerating effect induced by the structure of a-amino acid in the copper-catalyzed coupling reaction of aryl halides with a-amino acids. Synthesis of benzolactam-V8. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:12459–67. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Xu L-W, Xia C-G, Li J-W, et al. Efficient palladium/copper-cocatalyzed C-N coupling reaction of unactivated aryl bromide or iodide with amino acid under microwave heating. Catal. Commun. 2004;5:121–3. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sharp TL, Dence CS, Engelbach JA, et al. Techniques necessary for multiple tracer quantitative small-animal imaging studies. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2005;32:875–84. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]