Abstract

Intracellular signalling emanating from the B-cell antigen receptor is considered to follow a discrete course that requires participation by a set of mediators, grouped together as the signalosome, in order for downstream events to occur. Recent work indicates that this paradigm is true only for naïve B cells. Following engagement of the IL-4 receptor, a new, alternate pathway for B-cell receptor (BCR)-triggered intracellular signalling is established that bypasses the need for signalosome elements and operates in parallel with the classical, signalosome-dependent pathway. Reliance on Lyn and sensitivity to rottlerin by the former, but not the latter, distinguishes these two pathways. The advent of alternate pathway signalling leads to production and secretion by B cells of osteopontin (Opn). As Opn is a polyclonal B-cell activator that is strongly associated with a number of autoimmune diseases including lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, this novel finding is likely to be clinically relevant. Our results highlight the potential role of B-cell-derived Opn in immunity and autoimmunity and suggest that stress-related IL-4 expression might act to strengthen immunoglobulin secretion at the risk of autoantibody formation. Further, these results illustrate receptor crosstalk in the form of reprogramming, whereby engagement of one receptor (IL-4R) produces an effect that persists after the original ligand (IL-4) is removed and results in alteration of the pathway, and outcome, of signalling via a second receptor (BCR) following its activation.

Keywords: autoimmunity, B cells, cytokines, signal transduction

Introduction

The role of B cells in autoimmune dyscrasias has been emphasized anew by the results of clinical trials in which treatment with anti-CD20 antibody (rituximab) produced improvement following B-cell depletion [1–5]. This has focused attention on the means by which B cells are triggered to become active participants in normal (anti-foreign antigen) and aberrant (anti-self antigen) immune responses. B-cell triggering and activation begins with antigen binding to the B-cell receptor (BCR) complex, which commences antigen-specific serological immune responses. Following antigen engagement, the BCR complex triggers a series of biochemical events that transduce the initial extracellular binding to the intracellular milieu, producing downstream changes that ultimately specify B-cell behaviour. The strength and nature of BCR signalling, along with contributions from receptors for T-cell products, cytokines and other molecules, determines how an encounter with antigen plays out for B cells in terms of activation, apoptosis, tolerance, memory and differentiation to immunoglobulin secretion. Thus, BCR engagement and resultant intracellular events are key to B-cell adaptive responses.

The subsequent passages recount recent work, which overturns a longstanding paradigm, regarding intracellular events in B cells by showing that BCR signalling can be reprogrammed through receptor crosstalk. In particular, we have found that IL-4 creates a new, parallel pathway for propagation of BCR-triggered events that leads to secretion of the pleiomorphic cytokine, osteopontin (Opn), whose expression by B cells has not been previously reported. The properties of Opn as a polyclonal B-cell activator and contributor to autoimmune disease suggest that this novel finding bears clinical relevance. During in vivo immune responses, the alternate pathway, via Opn, may be crucial for mediating beneficial immunoglobulin production, but may also induce unwanted autoantibody formation. This suggests a novel route to lupus and similar diseases in which stress-induced IL-4 reprograms BCR signalling leading to de novo expression of a cytokine that fosters aberrant secretion of antibodies that recognize self-determinants.

Classical BCR signalling depends on signalosome elements

Surface immunoglobulin (sIg) constitutes the antigen binding moiety of the B-cell receptor complex, which additionally consists of sIg-associated molecules Igα and Igβ (CD79a and CD79b) that are responsible for subsequent downstream events. The intracellular events that are triggered by sIg engagement have been studied extensively in vitro and this effort has led to a generally accepted paradigm. In brief, following BCR triggering, src kinase activation leads to a cascade of tyrosine phosphorylation events that activate intermediaries leading to PLCγ2, which in turn metabolizes PI(4,5)P2 to produce second messenger molecules that mobilize Ca++ and activate PKCβ. These and other mediators contribute to the activation by phosphorylation of the MAPK, ERK. Ca++, PKC and ERK are responsible, along with other molecules, for inducing and activating a number of transcription factors such as NF-AT, NF-κB and AP-1 that ultimately alter B-cell gene expression. Further details are provided in recent reviews [6–8].

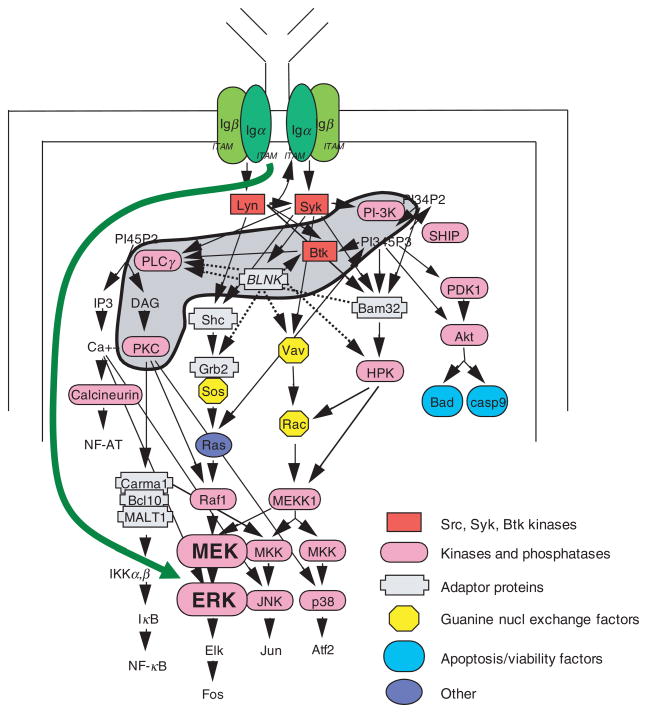

An important aspect of the paradigm described above is the collection of several early signalling molecules in a conceptual framework termed the signalosome [9] (see shaded area in Fig. 1). The prototypic molecule for this group is Btk, mutation of which results in severely blocked B-cell development in humans afflicted with X-linked agammaglobulinaemia (XLA), but a milder form of B-cell deficiency in mice with X-linked immunodeficiency (xid) in which numbers of mature B cells are reduced and T-cell-independent responses are diminished [10–12]. BCR signalling completely fails in xid and Btk-deficient B cells, as judged by the absence of proliferation and the lack of NF-κB activation produced by BCR engagement [13–17]. Even when sufficient Btk is provided to xid mice to normalize B cell development, BCR signalling is still impaired [18]. Equivalent phenotypes are found in mice with genetic deficiencies of the p85α subunit of PI-3K, the p110δ subunit of PI-3K, BLNK, PLCγ2 and PKCβ [19–31], which has led to the designation of these molecules as signalosome elements. Each of these signalosome molecules, possibly acting in concert under normal conditions, is individually required for successful BCR signal transduction.

Fig. 1.

IL-4 induces an alternate pathway for BCR signalling. Some elements involved in mediating BCR-triggered intracellular signalling are shown. Mediators grouped together as the signalosome (PI-3K, Btk, BLNK, PLCγ2, and PKCβ) are indicated by the shaded region. B cell treatment with IL-4 produces an alternate pathway for BCR signalling, shown as a green arrow, that bypasses the need for multiple signalosome elements to bring about the downstream event of ERK phosphorylation, which is dependent on MEK activation here as in the classical pathway for BCR signalling. However, IL-4 treatment does not alter the requirement of signalosome mediators for BCR-triggered NF-κB activation. IL-4 induction of the alternate pathway for BCR signalling to pERK requires time and protein synthesis.

IL-4 influences BCR signalling

IL-4 is a pleiotropic cytokine produced by multiple cell types (Th2 cells, NK T cells, eosinophils, basophils, mast cells) that plays a key role in normal B-cell physiology by enhancing proliferation, maintaining viability, fostering isotype switching and altering surface antigen expression (reviewed in [32]). The transcription factor STAT6 is the principal mediator for most of the effects of IL-4 on B cells as judged by examination of STAT6-deficient and STAT6-overexpressing mice [33–36].

The many effects of IL-4 on B cells include an association with tolerance disruption and autoantibody production [37, 38], both of which are components of autoimmune dyscrasias. In relation to this, it has long been known that IL-4 enhances B-cell proliferation in response to BCR engagement [39–43]. This enhancing effect presumably disrupts normal B-cell regulation and so has been the subject of much attention; however, the means by which IL-4 affects BCR-triggered events has never been fully clarified [42]. With previous work in mind [43], we hypothesized that the effect of IL-4 on BCR signalling might take place through a receptor crosstalk-dependent reprogramming mechanism that could affect normal and pathophysiological B-cell behaviour.

To test for an effect of IL-4 on BCR signalling, the distal downstream readout of ERK phosphorylation was evaluated, because the vast majority of ERK phosphorylation is dependent on signalosome signalling and is blocked by inhibitors of PI-3K and other signalosome elements [44–46], and because ERK is a particularly important event that is involved in directing B-cell behaviours of proliferation and differentiation [47–52].

IL-4 induces an alternate pathway for BCR signalling

Considering the indispensable role of the signalosome in naïve B cells as noted above, BCR signalling that produces ERK phosphorylation in spite of PI-3K inhibition or inhibition of other signalosome elements must, of necessity, occur through a new, nonclassical pathway that does not involve signalosome elements. This is exactly what we found when B cells were stimulated through the BCR after IL-4 treatment [53]. Whereas in naïve B cells, BCR signalling for ERK phosphorylation (pERK) was completely blocked by inhibitors of PI-3K, or PLC, or PKCβ, as expected [46], BCR signalling in IL-4-treated B cells succeeded in propagating to pERK despite the presence of the very same signalosome inhibitors [53, 54]. Thus, the classical signalosome-dependence of BCR signalling for ERK phosphorylation was circumvented, or bypassed, by prior B-cell exposure to IL-4. Another way of conceptualizing these results is that IL-4 reprograms BCR signalling so that PI-3K and other signalosome elements are no longer required for the downstream event of ERK phosphorylation. The new, signalosome-independent pathway for BCR signalling that is induced by IL-4 is termed the alternate pathway, in contradistinction to the signalosome-dependent classical pathway.

As with many other IL-4 effects [33–35], the capacity of IL-4 to produce an alternate BCR signalling pathway depends on STAT6. This is consistent with the need for macromolecular synthesis to establish the IL-4-induced alternate pathway. Of interest, IL-4 is unique amongst a large number of other STAT-activating cytokines that failed to produce alternate pathway BCR signalling [53]. Thus, reprogramming that produces the alternate signalling pathway is specific to IL-4. Moreover, the alternate pathway that is produced by IL-4-induced reprogramming is specific to ERK, because another typical outcome of BCR signalling, namely NF-κB activation [55], remains signalosome-dependent even after B-cell treatment with IL-4 [53]. Thus, IL-4-induced reprogramming of intracellular signalling affects the pathway leading from BCR to ERK but not from BCR to NF-κB. These results indicate that production of the alternate pathway for BCR signalling is not a general reaction to binding of any cytokine, nor are all downstream events reprogrammed; instead, alternate pathway signalling is a unique outcome of IL-4 exposure that specifically affects ERK activation. Thus, IL-4 exposure induces a new pathway for BCR signalling that is not part of the repertoire of naïve B cells. See Fig. 1.

The IL-4-induced alternate pathway operates in parallel with the classical pathway

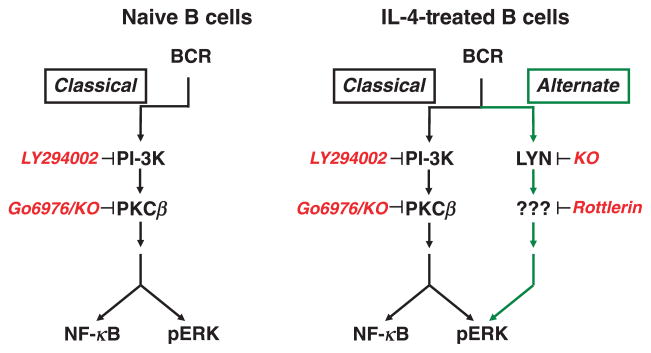

Further study of alternate pathway signalling using inhibitors of different PKC family members indicated that the alternate BCR signalling pathway produced by IL-4 does not replace the classical pathway, but rather operates in parallel with it. In other words, in naïve B cells, only the classical, signalosome-dependent pathway exists, but after B-cell exposure to IL-4, the new alternate pathway is added to the classical pathway, such that two pathways for BCR signalling operate at the same time. See Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The IL-4-induced alternate pathway operates in parallel with the classical pathway, is blocked by rottlerin, and depends on Lyn. Several key elements of the classical (black arrows) and alternate (green arrows) BCR signalling pathways are shown. Naïve B cells contain only one signalling pathway that is entirely dependent on signalosome elements such as PI-3K or PKCβ. IL-4 treatment produces a new, alternate pathway for BCR signalling that operates in parallel alongside, but does not replace, the classical pathway. The alternate pathway does not utilize signalosome elements but, in contrast to the classical pathway, requires Lyn and a rottlerin-inhibitable factor. Complete interruption of BCR-triggered ERK phosphorylation in IL-4-treated B cells requires separate inhibition of both the classical and the alternate pathways with, for example, the combination of LY294002 plus rottlerin.

The recognition that two pathways exist in IL-4-treated B cells was facilitated by the discovery that the kinase inhibitor, rottlerin [56], specifically blocks the alternate pathway [54]. As noted above, in naïve B cells, signalosome inhibitors, such as LY294002 (blocks PI-3K), U73122 (blocks PLC) or Go6976 (blocks PKCβ), completely abrogate BCR signalling for ERK phosphorylation because only the one (classical) pathway is present. After B-cell treatment with IL-4, none of these inhibitors eliminates BCR signalling for ERK phosphorylation, because the alternate pathway is operative even though the classical pathway is blocked; conversely, rottlerin fails to abrogate BCR signalling for ERK phosphorylation because the classical pathway is operative even though the alternate pathway is blocked. Thus, in IL-4-treated B cells, in which both the classical and the alternate pathways for BCR signalling co-exist, BCR signalling for ERK phosphorylation is interrupted only by combining a signalosome inhibitor (such as LY294002 or U73122 or Go6976) and rottlerin, not by one or the other alone [54]. Only by inhibiting both pathways simultaneously is BCR signalling for ERK phosphorylation terminated. See Fig. 2.

Our two pathway model holds that the classical and alternate pathways are separate and distinct. This model predicts that B cells from PKCβ-deficient mice that lack the classical, signalosome-dependent signalling pathway and thus fail to phosphorylate ERK after BCR engagement, should, after IL-4 treatment, express the alternate signalling pathway and re-acquire the ability to induce pERK. This is exactly what was found [54]. Thus, a key prediction of the dual pathway model specifying parallel propagation of classical and alternate BCR signalling in IL-4-treated B cells is validated by this knock-out model.

Lyn is a key mediator of the IL-4-induced alternate pathway and not the classical pathway

Confidence in the proposition that the alternate pathway is separate and distinct would be enhanced by finding a signalling mediator that is required for alternate pathway signalling and not classical pathway signalling. The src kinase, Lyn, represents such a mediator. Despite its abundance in B cells, Lyn (reviewed in [57, 58]) is not required for classical pathway signalling [59–61], as evidenced by normal BCR-triggered ERK phosphorylation in naïve, Lyn-deficient B cells. However, these same Lyn-deficient B cells are incapable of generating an alternate BCR signalling pathway after IL-4 treatment [54]. Thus, in Lyn-deficient B cells, BCR signalling for ERK phosphorylation remains signalosome-dependent and is completely blocked by any one of the signalosome inhibitors discussed above. These results indicate that the IL-4-induced alternate pathway for BCR signalling absolutely depends on Lyn kinase, even though Lyn is not required for BCR signalling to pERK via the classical pathway. See Fig. 2.

It is well to remember that Lyn is a constitutive component of B cells and presumably available, even before B-cell treatment with IL-4, to propagate BCR signalling via the alternate pathway. Thus, it may be presumed that Lyn itself, or a Lyn interacting factor, is changed by IL-4R/STAT6 signalling, in such a way that the alternate pathway is assembled. Clearly, the macromolecular synthesis required for IL-4-mediated induction of the alternate pathway could involve adaptor molecules, substrates or mediators downstream (or upstream) of Lyn. Regardless of the mechanism by which pre-existing Lyn becomes oriented toward the alternate pathway of BCR signalling, Lyn is the first mediator identified that is required specifically for the alternate pathway that is not a necessary part of the classical pathway for BCR signalling, as assessed by terminal ERK phosphorylation. It is interesting to note that the early described effects of IL-4 on anti-Ig-stimulated proliferation were reported to be abolished in Lyn-deficient B cells [59], which, in view of the requirement for Lyn in alternate pathway signalling, suggests that the alternate pathway may be the means by which IL-4 exerts its long-known enhancing effect on anti-Ig-induced B-cell stimulation.

Osteopontin (Opn/Eta-1/SPP1) expression is a specific outcome of alternate pathway signalling

The alternate pathway, operating in parallel with the classical pathway, would seem capable of strengthening BCR signalling by enhancing certain outcomes, such as ERK activation, which leads to diminished BCL-6, and that in turn fosters B-cell differentiation to immunoglobulin secretion. But beyond simply boosting classically determined outcomes, it would seem equally plausible that the alternate pathway might encode a different kind of B-cell response, one not triggered at all by BCR signalling via the classical pathway. This latter possibility is particularly intriguing because it might speak directly to the raison d’etre, the physiological function, of the alternate pathway. To address this issue, RNA transcripts were examined in microarray experiments that compared B cells under four conditions: naïve; anti-Ig-stimulated for 4 h; IL-4-treated for 24 h; and, IL-4 treated for 24 h and then anti-Ig stimulated for 4 h. From the lists of expressed transcripts were culled only those that were uniquely stimulated by anti-Ig in IL-4-treated B cells; that is, those whose expression was at least 2-fold greater in IL-4-treated/anti-Ig-stimulated B cells than in B cells that were exposed to anti-Ig alone, IL-4 alone or medium alone. This resulted in the identification of the transcript for Opn, an intriguing outcome because of the very strong connection of Opn to B-cell activity/hyperactivity and to serological autoimmunity [62].

Osteopontin is an approximately 60 kDa RGD-containing phosphoglycoprotein, also known and studied under the names early T lymphocyte activation 1 (Eta-1) and secreted phosphoprotein 1 (SPP1), that plays a role in diverse physiological and pathological processes involving multiple tissues [63–65]. Opn is secreted by many cell types, including T cells, dendritic cells and macrophages, although until now expression by B cells has not been reported [63]. Known receptors for Opn include αVβ1 integrins and CD44, through which Opn is thought to influence macrophage and T-cell chemotaxis and migration [66]. Beyond its role as a matrix protein affecting wound healing and bone deposition and its association with malignancy, Opn functions as a cytokine, activating dendritic cells, enhancing Th1 and inhibiting Th2 cytokine expression and costimulating T cell proliferation [67–73]. In addition, Opn has important effects on B cells. Opn is a polyclonal B-cell activator – recombinant and biochemically purified Opn stimulates immunoglobulin production by B cells in vitro, and transgenic, overexpressing Opn mice contain elevated serum levels of several isotypes [74, 75]. In keeping with the broad effects of Opn on the immune system, Opn-deficient mice are unusually susceptible to several infectious agents, such as L. monocytogenes, M. bovis and HSV-1 [71, 76, 77]. In addition, the gene encoding Opn maps to the murine rickettsial resistance (Ricr) locus and Ricr alleles that yield deficient production of Opn are associated with susceptibility to O. tsutsugamushi, the etiologic agent of scrub typhus [63, 78].

Of particular relevance is the intimate involvement of Opn in autoimmunity. This is evidenced by an impressive and diverse set of findings. (i) Opn is elevated in murine models of human lupus and other autoimmune dyscrasias including lpr/lpr lupus-like disease, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), and anti-collagen antibody-induced arthritis (CAIA); (ii) Opn is elevated in human systemic lupus erythematosis (SLE) and in other human autoimmune diseases including multiple sclerosis (MS) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [79–86]. Further, (iii) Opn deficiency results in delayed onset of polyclonal B-cell activation in lpr/lpr disease and amelioration of EAE and CAIA [82, 83, 87, 88]; (iv) an Opn polymorphism is associated with human SLE [89]. Note that all of these murine and human diseases are manifested by destructive autoantibody formation. Thus, it is very relevant that (v) anti-dsDNA antibodies that typify human lupus arise spontaneously in mice that overexpress Opn and have no other genetic abnormalities [75]. Although the observed effects in some of the situations described above may be influenced by non-B immune cells, the role of Opn in promoting polyclonal B-cell activation, autoantibody production and autoimmune dyscrasias is consistently and well documented.

In view of the connection between Opn and autoimmunity, it was important to confirm the microarray data through real-time PCR with RNA prepared from naïve and IL-4-treated B cells stimulated by anti-Ig. In fact, Opn expression was markedly upregulated (up to 40-fold) by BCR triggering only in IL-4-treated B cells and not in naïve B cells [62]. Along the same lines, Western blotting showed that Opn protein expression was upregulated by BCR triggering only in IL-4-treated B cells and not in naïve B cells [62]. B-cell secretion of Opn protein was then examined by ELISA and in line with the results above, Opn secretion was induced only when IL-4-treated B cells were stimulated via BCR engagement [62]. Together these results indicate that IL-4 treatment changes the outcome of BCR signalling by promoting the expression and secretion of Opn, which is not upregulated by BCR triggering via the classical pathway.

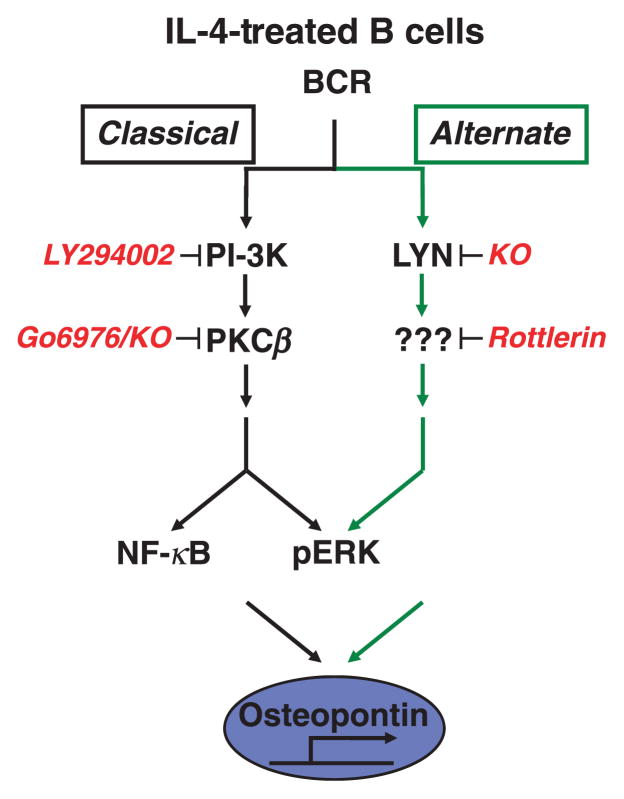

Because the alternate pathway operates in parallel with the classical pathway, Opn expression specific to BCR-stimulated, IL-4-treated B cells could derive from the alternate pathway alone or from contributions by both pathways. To address this issue, Opn RNA expression was examined in B cells exposed to inhibitors of the alternate pathway, the classical pathway or both together. Surprisingly, each of the inhibitors, alone or in combination, blocked Opn expression [62]. These results differ from those obtained with pERK as an end-point and strongly suggest that elements of both the alternate and the classical pathways for BCR signalling are required for upregulated Opn expression. See Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Osteopontin expression is a specific outcome of alternate pathway signalling. BCR triggering induces Opn expression and secretion in IL-4-treated B cells that signal via both the classical and alternate pathways, but not in naïve B cells, that only signal via the classical pathway. Inhibitor studies using LY294002 and rottlerin indicate that Opn expression results from the coordinate action of both pathways rather than the alternate pathway alone.

These results represent the first documentation that B cells express and secrete Opn. Because previous reports (see above) indicate that Opn plays an important role in fostering serological autoimmunity, it was of interest to determine the general magnitude of B-cell-derived Opn expression. To address this issue, the amount of Opn RNA induced and of Opn secreted by optimally stimulated B cells was measured and compared with that produced by optimally stimulated T cells. Over a 4 day period, the levels produced by appropriately stimulated B and T cells were similar, although gene expression and protein secretion occurred more rapidly in the former than in the latter [62]. In other words, operation of the alternate pathway leads to expression and secretion by B cells of a key B-cell-active cytokine in physiological amounts.

Summary

The results described herein demonstrate that IL-4, acting through STAT6 and relying on new macromolecular synthesis, induces a novel (alternate) pathway for BCR signalling to pERK that operates in parallel with the classical pathway for BCR signalling; however, the alternate pathway differs from the classical pathway in that it is signalosome-independent, requires Lyn and depends on a rottlerin-sensitive mediator. The alternate pathway fundamentally changes the way B cells respond to BCR triggering. Operation of the alternate pathway for BCR signalling (in conjunction with the classical pathway) results in the novel expression of Opn, a cytokine/chemokine/matrix protein, not previously reported to be expressed by B cells, that is associated with polyclonal B-cell activation and is strongly associated with autoimmunity.

There are several key implications of this work.

In B cell biology (as in many aspects of life), the past is prologue, and what has gone before, in the form of receptor crosstalk, changes or reprograms that which is yet to come. Thus, context is determinative for BCR signalling and perhaps for other cellular events in other cell types as well.

What is known and accepted about BCR signalling, particularly the central role of the signalosome, may be true only for naïve B cells and thus is likely deficient in describing how B cells respond during physiological and pathophysiological processes in vivo. In other words, the classical understanding of BCR signalling is limited by the subject matter for most studies of BCR signalling, namely, naïve B cells.

The IL-4-induced alternate pathway has the potential to strengthen BCR signalling for the generation of desired antibodies directed against foreign antigens through two mechanisms: (i) increased pERK would favour loss of BCL-6 and enhance differentiation to immunoglobulin secretion, inasmuch as pERK facilitates BCL-6 protein degradation; (ii) induction of Opn (in conjunction with the classical pathway) would enhance serological responses because Opn is a polyclonal B-cell activator.

The IL-4-induced alternate pathway has the potential to promote serological autoreactivity, because Opn is associated with autoantibody production and because IL-4 levels can be elevated as a result of severe infectious, allergic and other disorders [90–97]. Thus, at various times throughout life, B cells exposed to IL-4 in an antigen nonspecific fashion may facilitate the development of autoreactive immunoglobulin as a side effect of polyclonal B-cell activation, much as anti-dsDNA antibodies arise spontaneously in Opn transgenic mice. The induction of Opn expression via alternate pathway signalling may explain the known association of IL-4 with regulation/dysregulation of B-cell tolerance and expression of autoimmunity [37, 38, 98, 99], and the accumulation of autoantibodies with increasing age.

However, it may be further speculated that IL-4 is associated with autoimmunity through the strengthening of B-cell antigen receptor-triggered ERK activity that occurs via operation of the alternate pathway. Whereas lupus is associated with diminished ERK in T cells (through a mechanism involving DNA hypomethylation and induction of gene expression), recent evidence indicates that lupus disease activity is positively correlated with increased ERK activity when peripheral blood mononuclear cells are examined [100–102]. In as much as lupus T cells exhibit diminished ERK activity, this work may imply that B cells in lupus patients express heightened ERK activity. These considerations suggest that targeting Opn generally or in B cells, or targeting pERK specifically in B cells, may represent potential therapeutic strategies even as further details of the aberrant immune mechanisms responsible for lupus and other autoimmune diseases are deciphered.

In sum, the alternate pathway may be the key pathway operating during real in vivo immune responses, acting through Opn to strengthen immunoglobulin secretion at the risk of autoantibody formation. And the work described here, which began as an exploration of receptor crosstalk and reprogramming in B cells, suggests at the same time a new paradigm for the etiology of autoimmune disease and new targets for therapeutic intervention to reverse autoantibody production.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by USPHS grant AI075141 awarded by the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have nothing to declare.

References

- 1.Chambers SA, Isenberg D. Anti-B cell therapy (rituximab) in the treatment of autoimmune diseases. Lupus. 2005;14:210–4. doi: 10.1191/0961203305lu2138oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldblatt F, Isenberg DA. Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody in rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2008;181:163–81. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-73259-4_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tieng AT, Peeva E. B-cell-directed therapies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2008;38:218–27. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma Y. The potential utility of B cell-directed biologic therapy in autoimmune diseases. Rheumatol Int. 2008;28:205–15. doi: 10.1007/s00296-007-0471-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mease PJ. B cell-targeted therapy in autoimmune disease: rationale, mechanisms, and clinical application. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:1245–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niiro H, Clark EA. Regulation of B-cell fate by antigen-receptor signals. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:945–56. doi: 10.1038/nri955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurosaki T. Regulation of B-cell signal transduction by adaptor proteins. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:354–63. doi: 10.1038/nri801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gauld SB, Dal Porto JM, Cambier JC. B cell antigen receptor signaling: roles in cell development and disease. Science. 2002;296:1641–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1071546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fruman DA, Satterthwaite AB, Witte ON. Xid-like phenotypes: a B cell signalosome takes shape. Immunity. 2000;13:1–3. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsukada S, Saffran DC, Rawlings DJ, et al. Deficient expression of a B cell cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase in human X-linked agammaglobulinemia. Cell. 1993;72:279–90. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90667-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rawlings DJ, Saffran DC, Tsukada S, et al. Mutation of unique region of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase in immunodeficient XID mice. Science. 1993;261:358–61. doi: 10.1126/science.8332901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas JD, Sideras P, Smith CI, Vorechovsky I, Chapman V, Paul WE. Colocalization of X-linked agammaglobulinemia and X-linked immunodeficiency genes. Science. 1993;261:355–8. doi: 10.1126/science.8332900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sieckmann DG, Asofsky R, Mosier DE, Zitron IM, Paul WE. Activation of mouse lymphocytes by anti-immunoglobulin. I. Parameters of the proliferative response. J Exp Med. 1978;147:814–29. doi: 10.1084/jem.147.3.814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parker DC, Fothergill JJ, Wadsworth DC. B lymphocyte activation by insoluble anti-immunoglobulin: induction of immunoglobulin secretion by a T cell-dependent soluble factor. J Immunol. 1979;123:931–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khan WN, Alt FW, Gerstein RM, et al. Defective B cell development and function in Btk-deficient mice. Immunity. 1995;3:283–99. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90114-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bajpai UD, Zhang K, Teutsch M, Sen R, Wortis HH. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase links the B cell receptor to nuclear factor kappaB activation. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1735–44. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.10.1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petro JB, Rahman SM, Ballard DW, Khan WN. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase is required for activation of IkappaB kinase and nuclear factor kappaB in response to B cell receptor engagement. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1745–54. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.10.1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Satterthwaite AB, Cheroutre H, Khan WN, Sideras P, Witte ON. Btk dosage determines sensitivity to B cell antigen receptor cross-linking. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13, 152–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fruman DA, Snapper SB, Yballe CM, et al. Impaired B cell development and proliferation in absence of phosphoinositide 3-kinase p85alpha. Science. 1999;283:393–7. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5400.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki H, Terauchi Y, Fujiwara M, et al. Xid-like immunodeficiency in mice with disruption of the p85alpha subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Science. 1999;283:390–2. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5400.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jumaa H, Wollscheid B, Mitterer M, Wienands J, Reth M, Nielsen PJ. Abnormal development and function of B lymphocytes in mice deficient for the signaling adaptor protein SLP-65. Immunity. 1999;11:547–54. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pappu R, Cheng AM, Li B, et al. Requirement for B cell linker protein (BLNK) in B cell development. Science. 1999;286:1949–54. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5446.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang D, Feng J, Wen R, et al. Phospholipase Cgamma2 is essential in the functions of B cell and several Fc receptors. Immunity. 2000;13:25–35. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hashimoto A, Takeda K, Inaba M, et al. Cutting edge: essential role of phospholipase C-gamma 2 in B cell development and function. J Immunol. 2000;165:1738–42. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.4.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayashi K, Nittono R, Okamoto N, et al. The B cell-restricted adaptor BASH is required for normal development and antigen receptor-mediated activation of B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2755–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040575697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu S, Tan JE, Wong EP, Manickam A, Ponniah S, Lam KP. B cell development and activation defects resulting in xid-like immunodeficiency in BLNK/SLP-65-deficient mice. Int Immunol. 2000;12:397–404. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okkenhaug K, Bilancio A, Farjot G, et al. Impaired B and T cell antigen receptor signaling in p110delta PI 3-kinase mutant mice. Science. 2002;297:1031–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1073560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clayton E, Bardi G, Bell SE, et al. A crucial role for the p110delta subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in B cell development and activation. J Exp Med. 2002;196:753–63. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jou ST, Carpino N, Takahashi Y, et al. Essential, nonredundant role for the phosphoinositide 3-kinase p110delta in signaling by the B-cell receptor complex. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:8580–91. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.24.8580-8591.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saijo K, Mecklenbrauker I, Santana A, Leitger M, Schmedt C, Tarakhovsky A. Protein kinase C beta controls nuclear factor kappaB activation in B cells through selective regulation of the IkappaB kinase alpha. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1647–52. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Su TT, Guo B, Kawakami Y, et al. PKC-beta controls I kappa B kinase lipid raft recruitment and activation in response to BCR signaling. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:780–6. doi: 10.1038/ni823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paul WE. Interleukin 4: signalling mechanisms and control of T cell differentiation. Ciba Found Symp. 1997;204:208–16. doi: 10.1002/9780470515280.ch14. discussion 216–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaplan MH, Schindler U, Smiley ST, Grusby MJ. Stat6 is required for mediating responses to IL-4 and for development of Th2 cells. Immunity. 1996;4:313–9. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80439-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shimoda K, van Deursen J, Sangster MY, et al. Lack of IL-4-induced Th2 response and IgE class switching in mice with disrupted Stat6 gene. Nature. 1996;380:630–3. doi: 10.1038/380630a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takeda K, Tanaka T, Shi W, et al. Essential role of Stat6 in IL-4 signalling. Nature. 1996;380:627–30. doi: 10.1038/380627a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bruns HA, Schindler U, Kaplan MH. Expression of a constitutively active Stat6 in vivo alters lymphocyte homeostasis with distinct effects in T and B cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:3478–87. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Erb KJ, Ruger B, von Brevern M, Ryffel B, Schimpl A, Rivett K. Constitutive expression of interleukin (IL)-4 in vivo causes autoimmune-type disorders in mice. J Exp Med. 1997;185:329–39. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.2.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Foote LC, Evans JW, Cifuni JM, et al. Interleukin-4 produces a breakdown of tolerance in vivo with autoantibody formation and tissue damage. Autoimmunity. 2004;37:569–77. doi: 10.1080/08916930400020602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Howard M, Farrar J, Hilfiker M, et al. Identification of a T cell-derived b cell growth factor distinct from interleukin 2. J Exp Med. 1982;155:914–23. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.3.914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rabin EM, Ohara J, Paul WE. B-cell stimulatory factor 1 activates resting B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:2935–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.9.2935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rabin EM, Mond JJ, Ohara J, Paul WE. B cell stimulatory factor 1 (BSF-1) prepares resting B cells to enter S phase in response to anti-IgM and lipopolysaccharide. J Exp Med. 1986;164:517–31. doi: 10.1084/jem.164.2.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mizuguchi J, Beaven MA, Ohara J, Paul WE. BSF-1 action on resting B cells does not require elevation of inositol phospholipid metabolism or increased [Ca2+]i. J Immunol. 1986;137:2215–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hodgkin PD, Go NF, Cupp JE, Howard M. Interleukin-4 enhances anti-IgM stimulation of B cells by improving cell viability and by increasing the sensitivity of B cells to the anti-IgM signal. Cell Immunol. 1991;134:14–30. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(91)90327-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hashimoto A, Okada H, Jiang A, et al. Involvement of guanosine triphosphatases and phospholipase C-gamma2 in extracellular signal-regulated kinase, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase, and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation by the B cell antigen receptor. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1287–95. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.7.1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sakata N, Kawasome H, Terada N, Gerwins P, Johnson GL, Gelfand EW. Differential activation and regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinases through the antigen receptor and CD40 in human B cells. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:2999–3008. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199909)29:09<2999::AID-IMMU2999>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jacob A, Cooney D, Pradhan M, Coggeshall KM. Convergence of signaling pathways on the activation of ERK in B cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23420–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202485200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moriyama M, Yamochi T, Semba K, Akiyama T, Mori S. BCL-6 is phosphorylated at multiple sites in its serine- and proline-clustered region by mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) in vivo. Oncogene. 1997;14:2465–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fukuda T, Yoshida T, Okada S, et al. Disruption of the Bcl6 gene results in an impaired germinal center formation. J Exp Med. 1997;186:439–48. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.3.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Niu H, Ye BH, Dalla-Favera R. Antigen receptor signaling induces MAP kinase-mediated phosphorylation and degradation of the BCL-6 transcription factor. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1953–61. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.13.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Richards JD, Dave SH, Chou CH, Mamchak AA, DeFranco AL. Inhibition of the MEK/ERK signaling pathway blocks a subset of B cell responses to antigen. J Immunol. 2001;166:3855–64. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.3855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Piatelli MJ, Doughty C, Chiles TC. Requirement for a hsp90 chaperone-dependent MEK1/2-ERK pathway for B cell antigen receptor-induced cyclin D2 expression in mature B lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:12144–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200102200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tunyaplin C, Shaffer AL, Angelin-Duclos CD, Yu X, Staudt LM, Calame KL. Direct repression of prdm1 by Bcl-6 inhibits plasmacytic differentiation. J Immunol. 2004;173:1158–65. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guo B, Rothstein TL. B cell receptor (BCR) cross-talk: IL-4 creates an alternate pathway for BCR-induced ERK activation that is phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase independent. J Immunol. 2005;174:5375–81. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guo B, Blair D, Chiles TC, Lowell CA, Rothstein TL. Cutting Edge: B cell receptor (BCR) cross-talk: the IL-4-induced alternate pathway for BCR signaling operates in parallel with the classical pathway, is sensitive to Rottlerin, and depends on Lyn. J Immunol. 2007;178:4726–30. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.4726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Niiro H, Clark EA. Branches of the B cell antigen receptor pathway are directed by protein conduits Bam32 and Carma1. Immunity. 2003;19:637–40. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00303-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gschwendt M, Muller HJ, Kielbassa K, et al. Rottlerin, a novel protein kinase inhibitor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;199:93–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gauld SB, Cambier JC. Src-family kinases in B-cell development and signaling. Oncogene. 2004;23:8001–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu Y, Harder KW, Huntington ND, Hibbs ML, Tarlinton DM. Lyn tyrosine kinase: accentuating the positive and the negative. Immunity. 2005;22:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang J, Koizumi T, Watanabe T. Altered antigen receptor signaling and impaired Fas-mediated apoptosis of B cells in Lyn-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1996;184:831–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chan VW, Meng F, Soriano P, DeFranco AL, Lowell CA. Characterization of the B lymphocyte populations in Lyn-deficient mice and the role of Lyn in signal initiation and down-regulation. Immunity. 1997;7:69–81. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80511-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chan VW, Lowell CA, DeFranco AL. Defective negative regulation of antigen receptor signaling in Lyn-deficient B lymphocytes. Curr Biol. 1998;8:545–53. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guo B, Tumang JR, Rothstein TL. B cell receptor crosstalk: B cells express osteopontin through the combined action of the alternate and classical BCR signaling pathways. Mol Immunol. 2009;46:587–91. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Patarca R, Freeman GJ, Singh RP, et al. Structural and functional studies of the early T lymphocyte activation 1 (Eta-1) gene. Definition of a novel T cell-dependent response associated with genetic resistance to bacterial infection. J Exp Med. 1989;170:145–61. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.1.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.O’Regan A, Berman JS. Osteopontin: a key cytokine in cell-mediated and granulomatous inflammation. Int J Exp Pathol. 2000;81:373–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2613.2000.00163.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.O’Regan AW, Nau GJ, Chupp GL, Berman JS. Osteopontin (Eta-1) in cell-mediated immunity: teaching an old dog new tricks. Immunol Today. 2000;21:475–8. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01715-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Denhardt DT, Giachelli CM, Rittling SR. Role of osteopontin in cellular signaling and toxicant injury. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41:723–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Senger DR, Wirth DF, Hynes RO. Transformation-specific secreted phosophoproteins. Nature. 1980;286:619–21. doi: 10.1038/286619a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Oldberg A, Franzen A, Heinegard D. Cloning and sequence analysis of rat bone sialoprotein (osteopontin) cDNA reveals an Arg-Gly-Asp cell-binding sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:8819–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.23.8819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brown LF, Papadopoulos-Sergiou A, Berse B, et al. Osteopontin expression and distribution in human carcinomas. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:610–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liaw L, Birk DE, Ballas CB, Whitsitt JS, Davidson JM, Hogan BL. Altered wound healing in mice lacking a functional osteopontin gene (spp1) J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1468–78. doi: 10.1172/JCI1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ashkar S, Weber GF, Panoutsakopoulou V, et al. Eta-1 (osteopontin): an early component of type-1 (cell-mediated) immunity. Science. 2000;287:860–4. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5454.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.O’Regan AW, Hayden JM, Berman JS. Osteopontin augments CD3-mediated interferon-gamma and CD40 ligand expression by T cells, which results in IL-12 production from peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;68:495–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shinohara ML, Jansson M, Hwang ES, Werneck MB, Glimcher LH, Cantor H. T-bet-dependent expression of osteopontin contributes to T cell polarization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17101–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508666102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lampe MA, Patarca R, Iregui MV, Cantor H. Polyclonal B cell activation by the Eta-1 cytokine and the development of systemic autoimmune disease. J Immunol. 1991;147:2902–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Iizuka J, Katagiri Y, Tada N, et al. Introduction of an osteopontin gene confers the increase in B1 cell population and the production of anti-DNA autoantibodies. Lab Invest. 1998;78:1523–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nau GJ, Liaw L, Chupp GL, Berman JS, Hogan BL, Young RA. Attenuated host resistance against Mycobacterium bovis BCG infection in mice lacking osteopontin. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4223–30. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.4223-4230.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Abel B, Freigang S, Bachmann MF, Boschert U, Kopf M. Osteopontin is not required for the development of Th1 responses and viral immunity. J Immunol. 2005;175:6006–13. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.6006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Patarca R, Saavedra RA, Cantor H. Molecular and cellular basis of genetic resistance to bacterial infection: the role of the early T-lymphocyte activation-1/osteopontin gene. Crit Rev Immunol. 1993;13:225–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Patarca R, Wei FY, Singh P, Morasso MI, Cantor H. Dysregulated expression of the T cell cytokine Eta-1 in CD4-8- lymphocytes during the development of murine autoimmune disease. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1177–83. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.4.1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Katagiri Y, Mori K, Hara T, Tanaka K, Murakami M, Uede T. Functional analysis of the osteopontin molecule. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;760:371–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb44660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hudkins KL, Giachelli CM, Eitner F, Couser WG, Johnson RJ, Alpers CE. Osteopontin expression in human crescentic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 2000;57:105–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chabas D, Baranzini SE, Mitchell D, et al. The influence of the proinflammatory cytokine, osteopontin, on autoimmune demye-linating disease. Science. 2001;294:1731–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1062960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yumoto K, Ishijima M, Rittling SR, et al. Osteopontin deficiency protects joints against destruction in anti-type II collagen antibody-induced arthritis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:4556–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052523599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ohshima S, Yamaguchi N, Nishioka K, et al. Enhanced local production of osteopontin in rheumatoid joints. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:2061–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Comabella M, Pericot I, Goertsches R, et al. Plasma osteopontin levels in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;158:231–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Xu G, Nie H, Li N, et al. Role of osteopontin in amplification and perpetuation of rheumatoid synovitis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1060–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI23273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Weber GF, Cantor H. Differential roles of osteopontin/Eta-1 in early and late lpr disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001;126:578–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01702.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jansson M, Panoutsakopoulou V, Baker J, Klein L, Cantor H. Cutting edge: attenuated experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in eta-1/osteopontin-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2002;168:2096–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.5.2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Forton AC, Petri MA, Goldman D, Sullivan KE. An osteopontin (SPP1) polymorphism is associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Hum Mutat. 2002;19:459. doi: 10.1002/humu.9025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.DiPiro JT, Howdieshell TR, Goddard JK, Callaway DB, Hamilton RG, Mansberger AR., Jr Association of interleukin-4 plasma levels with traumatic injury and clinical course. Arch Surg. 1995;130:1159–62. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430110017004. discussion 1162–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schmidt E, Bastian B, Dummer R, Tony HP, Brocker EB, Zillikens D. Detection of elevated levels of IL-4, IL-6, and IL-10 in blister fluid of bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol Res. 1996;288:353–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02507102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Inoue N, Inoue M, Kuriki K, et al. Interleukin 4 is a crucial cytokine in controlling Trypanosoma brucei gambiense infection in mice. Vet Parasitol. 1999;86:173–84. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(99)00143-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Song GY, Chung CS, Chaudry IH, Ayala A. IL-4-induced activation of the Stat6 pathway contributes to the suppression of cell-mediated immunity and death in sepsis. Surgery. 2000;128:133–8. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.107282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chen D, Copeman DB, Burnell J, Hutchinson GW. Helper T cell and antibody responses to infection of CBA mice with Babesia microti. Parasite Immunol. 2000;22:81–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.2000.00279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wise GJ, Marella VK, Talluri G, Shirazian D. Cytokine variations in patients with hormone treated prostate cancer. J Urol. 2000;164:722–5. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200009010-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Uchio E, Ono SY, Ikezawa Z, Ohno S. Tear levels of inter-feron-gamma, interleukin (IL) -2, IL-4 and IL-5 in patients with vernal keratoconjunctivitis, atopic keratoconjunctivitis and allergic conjunctivitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2000;30:103–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Akpolat N, Yahsi S, Godekmerdan A, Demirbag K, Yalniz M. Relationship between serum cytokine levels and histopathological changes of liver in patients with hepatitis B. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3260–3. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i21.3260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Burstein HJ, Tepper RI, Leder P, Abbas AK. Humoral immune functions in IL-4 transgenic mice. J Immunol. 1991;147:2950–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Foote LC, Howard RG, Marshak-Rothstein A, Rothstein TL. IL-4 induces Fas resistance in B cells. J Immunol. 1996;157:2749–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Deng C, Kaplan MJ, Yang J, et al. Decreased Ras-mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling may cause DNA hypomethylation in T lymphocytes from lupus patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:397–407. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200102)44:2<397::AID-ANR59>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Molad Y, Amit-Vazina M, Bloch O, Yona E, Rapoport MJ. Increased ERK and JNK activities correlate with disease activity in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009 doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.102780. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gorelik G, Richardson B. Aberrant T cell ERK pathway signaling and chromatin structure in lupus. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;8:196–8. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2008.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]