Abstract

Background

There is no effective second line systemic chemotherapy for patients with disease progression following cisplatin-based chemotherapy. A phase II trial of sorafenib was performed to determine the activity and toxicity of this agent in a multiinstitutional setting in patients previously treated with 1 prior chemotherapy regimen.

Methods

27 patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma were treated with sorafenib 400 mg orally twice daily continuously until progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Results

There were no objective responses observed. The 4-month progression free survival (PFS) rate was 9.5% , median overall survival of the group was 6.8 months. There were no therapy related deaths, and common grade 3 toxicities included fatigue and hand-foot syndrome

Conclusions

Although sorafenib as a single agent has minimal activity in patients with advanced urothelial cancer in the second line setting, further investigation of tyrosine kinase inhibitors using different trial designs with PFS endpoints is warranted.

Keywords: urothelial cancer, sorafenib

Over the last 20 years, cisplatin-based chemotherapy has been established as the standard of care in the management of patients with advanced urothelial cancer. For the fit patient with preserved renal function, cisplatin based-multiagent chemotherapy with either gemcitabine+ cisplatin (GC) or methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, cisplatin (M-VAC) is supported by randomized trial evidence of benefit.1, 2 Unfortunately only a relatively small percentage of patients are cured with either GC or M-VAC.3, 4

During the past two decades a clinically evident stage migration5 has led to earlier appreciation of metastatic disease. Concomitantly there has been an increased utilization of neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy resulting in an increasing proportion of patients fit enough to be considered for second-line chemotherapy for metastatic disease. Recent phase II studies evaluating second line chemotherapy have demonstrated objective response rates in 10–25% range for a variety of single agents and combination regimens.6–8 Although patients with a reasonable performance status who develop progressive metastatic disease following front-line, platinum-based chemotherapy are frequently treated with salvage chemotherapy, this is done primarily with palliative intent as there is no evidence that such therapy improves progression free or overall survival.9 Urothlelial cancer has a myriad of molecular targets that make it attractive for the investigation of novel agents, however, in contrast to the more common epithelial cancers there have been limited efforts to evaluate novel agents in this disease. Although the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is frequently overexpressed in high grade urothelial cancer, several small phase II trials of EGFR targeted agents have failed to demonstrate meaningful activity.10, 11

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) binds to its cognate receptors, VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 to induce cell proliferation and migration. VEGF receptors are expressed on urothelial carcinomas and there is both preclinical and some clinical evidence supporting the antitumor efficacy of targeting this pathway.12–14

Sorafenib is a multikinase inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2), VEGFR-3, and platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta (PDGFR-beta).15 Phase III trials evidence of improvement in progression free survival for patients with clear renal cell carcinoma and hepatoma led to regulatory approval of sorafenib in these two relatively chemotherapy resistant epithelial neoplasms.16, 17

Based upon the need for more active agents and the overexpression of VEGF and VEFGR in many patients with advanced urothelial cancer. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group investigated sorafenib in patients with progressive advanced urothelial cancer following front-line chemotherapy.

METHODS

Eligible patients had histologically confirmed transitional cell carcinoma (or mixed histologies containing a component of transitional cell carcinoma) of the urothelium with evidence of progressive, bidimensionally measurable regional or metastatic disease. Patients must have been disease-free from prior malignancies for at least 5 years, with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 to 1 at entry. Patients must have demonstrated progressive disease after one and only one prior systemic chemotherapy regimen administered in the metastatic setting. Prior perioperative therapy either in the neoadjuvant or adjuvant setting was permitted, provided that it was completed more than 12 months prior to the chemotherapy administered in the metastatic setting. Patients must have been at least 4 weeks out from major surgery. Adequate renal and hepatic function were required with a serum creatinine < 1.5 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) ≤ 2.5 and bilirubin < 1.5 times the upper limit of normal. Adequate bone marrow reserve was mandated with a requirement for neutrophils ≥ 1,500 mm3 and a platelet count ≥ 100,000 /μL at entry. Patients requiring ongoing therapeutic anticoagulation, cytochrome p450 enzyme inducing antiepileptic drugs or a history of a bleeding diathesis were excluded. Sorafenib was administered orally at a dose of 400 mg (2 tablets) orally twice daily for a total daily dose of 800 mg. One cycle consisted of 56 days of therapy. Patients were mandated to monitor and record their blood pressure weekly during cycle one, then every cycle . No dose escalation was permitted, dose modifications were mandated as follows dose level 2: 400 mg/day, dose level 3: 400 mg every other day. Dose modifications were specified for myelopsuppression and mandated for any grade 3 or 4 toxicity.

Prior to study entry, all patients underwent physical examination and had their ECOG performance status and weight documented. There also were pretherapy complete blood count (CBC) and differential, serum creatinine, BUN, AST, bilirubin, and computed tomograms (CT) of chest, abdomen and pelvis. A CBC and the above chemistries were repeated on the first day of each subsequent therapy cycle. Tumor measurements were performed with each cycle of therapy. Each site was required to have approval of this clinical trial by a local Human Investigations Committee in accord with an assurance filed with and approved by the Department of Health and Human Services. All patients provided written informed consent prior to registration onto this study.

Tumor responses were analyzed using RECIST criteria. National Cancer Institute (NCI) common toxicity criteria (CTCAE v. 3) were used to analyze toxicity. Patients with objective responses or stable disease were continued on therapy until development of unacceptable toxicity.

The primary goal of this study was to evaluate the 4-month progression free survival (PFS) rate in patients treated with sorafenib. If this treatment showed evidence of at least a 50% PFS rate at four months, it would be considered as a promising therapy for further study. A PFS rate of 30% or less would not be of interest. This cohort employed a two-stage design with 4-month PFS rate as the primary endpoint. At the initial stage, 20 eligible patients were to be entered and accrual was to be suspended. The first stage stopping rule was based on response rates. Responses were assessed using RECIST. If no objective response was observed in the first 20 eligible patients, the trial would be terminated. Based on this stopping rule, the probability of terminating the study early was 0.54 if the true underlying response rate was 3% and 0.04 if the true rate was 15%. If one or more responses were observed in the first 20 eligible patients, the study was to accrue an additional 19 eligible patients for a total of 39 eligible patients. If 16 or more patients were alive and progression-free at four months among the 39 eligible patients, the treatment would be considered worthy of further consideration in this population.

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the characteristics of the patients at study entry. Exact binomial confidence intervals were computed for response rates. The method of Kaplan and Meier was used to characterize overall survival and progression-free survival.18 Overall survival was computed from the time of registration to death. Progression-free survival was computed from the time of registration to death or progression whichever occurred first. For patients who were still alive and progression free, then this patient was censored at the date of last disease assessment.

RESULTS

From October of 2005 through October of 2006 , 27 patients from 14 ECOG institutions were entered to the study and are evaluable for toxicity. Five of these patients were classified as ineligible and were only included in toxicity evaluations, two patients had ineligible lab values for entry, one had a second cancer and two were enrolled prior to the 4 week interval from prior systemic therapy.

Patient Characteristics

All twenty-two eligible patients had tumors that were histologically pure or predominantly transitional cell carcinoma. Patients ranged in age from 37 to 81, with a median of 66. Most patients were white (95%) and male (64%). With respect to ECOG performance status (PS), 36% patients were fully active (PS 0), and 64% had PS 1. Fifteen patients (68%) had bladder as the site of tumor. Using the risk factor status defined by Bajorin three patients (14%) had zero risk factors, and 19 (86%) had one risk factor.19 All the 22 patients had been treated with multi-agent cytotoxic systemic chemotherapy, 17 patients (77%) had undergone surgery with therapeutic intent, and 6 (27%) had prior radiation therapy. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics

| Characteristics | No. of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, yr median (range) | 66 (37–81) |

| Sex | |

| Men | 14 (64) |

| Women | 8 (36) |

| ECOG performance status | |

| 0 | 8 (36) |

| 1 | 14 (64) |

| Sites of metastases | |

| Distant nodes | 8 (36) |

| Liver | 10 (46) |

| Bone | 9 (41) |

| Lung | 14 (64) |

| Prognostic factors (MSK)* | |

| 0 | 3 (14) |

| 1 | 19 (86) |

|

| |

| ECOG indicates Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group | |

MSK Memorial Sloan Kettering, Bajorin et al.19

Response Assessment

No response was observed among eligible patients. Three patients (14%) had stable disease and 9 (41%) had progression as their best overall response. Ten other patients were deemed unevaluable for response, six patients had at least one follow-up assessment, however, they were not performed within the mandated time frame, the remainder did not have follow-up imaging before death or removal from study either from clinical deterioration or therapy related toxicity. Fifteen patients (68%) went off treatment due to disease progression, and 4 (18%) due to excessive toxicity. Thirteen patients (59%) received only one cycle of protocol therapy, 8 (36%) received 2 cycles, and 1 (5%) received 4 cycles. Median number of cycles administered was 1 (range, 1–4).

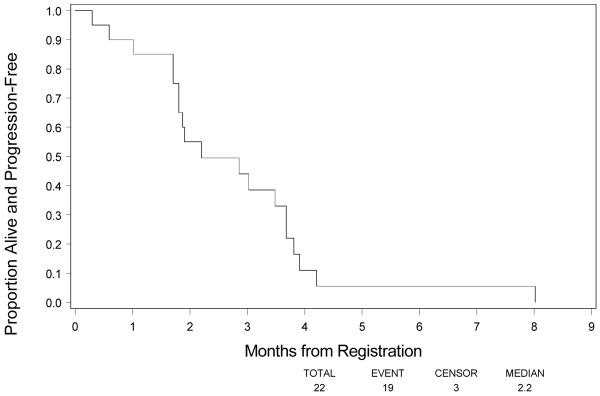

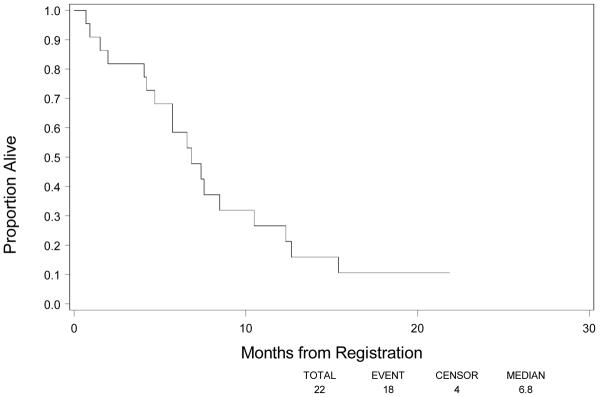

Among the 22 eligible patients, 18 (82%) had progressed and died as of March 5th , 2008. Figure 1 shows PFS. The 4-month PFS rate based on Kaplan-Meier method was 11.0% (90% CI, 0–23.0%). Median PFS was 2.2 months (90% CI, 1.8–3.7 months). Median survival was 6.8 months (90% CI, 5.7–8.5 months). (Fig 2)

Figure 1.

Progression Free Survival

Figure 2.

Overall Survival

Toxicity

Toxicity from sorafenib was similar to that seen in a renal cancer population. There were no therapy related deaths. Two patients experienced Grade 4 pulmonary embolism (7.0%). Common Grade 3 toxicities included fatigue and hand-foot reaction, each occurring in five patients (19%).

DISCUSSION

Despite the availability of a number of conventional cytotoxics with anti-tumor activity in patients with disease progresses ion following platinum-based chemotherapy, there remains limited evidence that any single agent or combination regimen improves patient outcome.9 Bellmunt and colleagues recently reported the results of a phase III trial comparing vinflunine ( a microtubule inhibitor) plus best supportive care versus best supportive care alone in patients with advanced urothelial cancer whose disease had progressive following platinum-based chemotherapy.20 Therapy was relatively well tolerated and although there was a median 2-mo survival advantage (6.9 vs 4.6 mo), favouring the vinflunine arm, this difference had not yet achieved statistical significance at the time of its initial report.

There have been a small number of small phase II trials of targeted agents in advanced urothelial cancer, all but one in the salvage setting.

The potential for synergy between trastuzumab and active chemotherapeutic agents in advanced urothelial cancer such as paclitaxel and carboplatin and reports of Her-2/neu expression in urothelial cancers ranging from approximately 10–80% led Hussein and colleagues to conduct a multicenter phase II trial of trastuzumab in combination with , paclitaxel, carboplatin and gemcitabine. Eligible patients were required to have locally recurrent or metastatic disease, without prior chemotherapy for metastatic disease. As the primary endpoint of the study was cardiac toxicity, patients were mandated to have an ejection fraction greater than 50% and no evidence of ischemic heart disease. Her-2/neu overexpression by either IHC, FISH or elevated serum Her-2/neu -ECD was required.

Forty-four of 57 Her-2/neu–positive patients received protocol therapy. Myelosuppression was the most common grade 3 and 4 toxicity, with 23 % of patients manifesting grade 1 to 3 cardiac toxicity. There were two therapy-related deaths. Thirty-one (70%) of 44 patients responded (five complete and 26 partial), and 25 (57%) of 44 were confirmed responses. Median survival was 14.1 months.21

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is over expressed in high grade urothelial cancers and the availability of a variety of EGFR targeting agents made this an attractive target.22 In a phase II trial of gefitinib in the second line setting, SWOG investigators observed only 1 partial response (3%) in 29 enrolled patients.23 A CALGB study of cisplatin + fixed dose rate gemcitabine + gefitinib was stopped early secondary to unacceptable therapy related toxicity primarily from the fixed dose gemcitabine and therefore the value of adding gefitinib to the regimen was unevaluable.11 Wülfing et al. conducted a phase II trial of lapatinib (reversible dual inhibitor of ErbB1 and ErbB2 tyrosine kinases) in patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer following progression on a cisplatin-based regimen. Eligible patients were required to manifest expression by immunohistochemistry of either Her 1 or Her 2. Although therapy was well tolerated, only 1 of 59 enrolled patients demonstrated an objective response to therapy.10 Unlike other epithelial cancers in which EGFR domain mutations are relatively well understood, there is limited data in urothelial cancer, and additional studies using monoclonal antibodies in combination with chemotherapy are planned.

Investigators at Memorial Sloan Kettering conducted a single institution phase II trial of sunitinib in patients with advanced disease progressing on front-line chemotherapy for advanced disease. Sunitinib was administered in conventional 6 week cycles, 50 mg/day × 4 weeks, 2 weeks off. Forty-five patients were enrolled and toxicity was as would be expected with this agent although one patient died of therapy related complications. . Of 41 evaluable patients, 3 achieved a confirmed partial response with an additional 11 patients achieving stable disease. Further follow-up will be needed to define time to disease progression and survival. An additional cohort of patients have been enrolled to study a continuous 37.5 mg dosing schedule.24

The current study demonstrates that sorafenib at 400 mg bid has no clinically meaningful activity in patients with advanced urothelial cancer following front-line chemotherapy. In retrospect, given the evolving understanding of sorafenib's level of activity in advanced renal cancer, it is not surprising, that most patients manifested early disease progression. Given the aggressive nature of advanced urothelial cancer, only an agent or combination of agents with the ability to produce rapid objective responses will likely demonstrate obvious clinical activity in this setting. Testing agents like sorafenib in other settings of advanced urothelial cancer, i.e. as maintenance therapy following an objective response to conventional cyotoxics using disease free progression as a primary end point, may provide a better assessment of this class of agents in this disease.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (Robert L. Comis, M.D.) and supported in part by Public Health Service Grants CA23318, CA66636, CA21115, CA49957, CA21076 and from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health and the Department of Health and Human Services. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute.

References

- 1.von der Maase H, Hansen S, Roberts J, Dogliotti L, Oliver T, Moore M, et al. Gemcitabine and cisplatin versus methotrextate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in advanced or metastatic bladder cancer: results of a large, randomized, multinational, multicenter, phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3068–77. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.17.3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loehrer P, Einhorn L, Elson P, Crawford E, Kuebler P, Tannock I, et al. A randomized comparison of cisplatin alone or in combination with methotrexate, vinblastine, and doxorubicin in patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma: A cooperative group study. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:1066–73. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.7.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von der Maase H, Sengelov L, Roberts J, Ricci S, Dogliotti L, Oliver T, et al. Long-term survival results of a randomized trial comparing gemcitabine plus cisplatin, with methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, plus cisplatin in patients with bladder cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4602–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saxman S, Propert K, Einhorn L, Crawford E, Tannock I, Raghavan D, et al. Long-term follow-up of a phase III intergroup study of cisplatin alone or in combination with methotrexate, vinblastine, and doxorubicin in patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma: A Cooperative Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2564–69. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.7.2564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raghavan D. Advanced bladder and urothelial cancers. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36(Suppl 2):1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Witte RS, Elson P, Bono B, et al. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group phase II trial of ifosfamide in the treatment of previously treated advanced urothelial carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:589–93. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.2.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCaffrey JA, Hilton S, Mazumdar M, et al. Phase II randomized trial of gallium nitrate plus fluorouracil versus methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in patients with advanced transitional-cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2449–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krege S, Rembrink V, Borgermann CH, Otto T, Rubben H. Docetaxel and ifosfamide as second line treatment for patients with advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer after failure of platinum chemotherapy: A phase 2 study. J Urol. 2001;165:67–71. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200101000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallagher D, Milowsky M, Bajorin D. Advanced bladder cancer: status of first-line chemotherapy and the search for active agents in the second-line setting. Cancer. 2008;113:1284–93. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wülfing C, Machiels J, Richel D, Grimm M, Treiber U, deGroot M, et al. A single arm, multicenter, open label, phase II study of lapatinib as treatement of patients with locally advanced/metastatic transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelial tract. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2005 abst 4594. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Philips G, Halabi S, Sanford B, Bajorin D, Small E. A phase II trial of cisplatin, fixed dose-rate gemcitabine and gefitinib for advanced urothelial tract carcinoma: results of the Cancer and Leukaemia Group B 90102. BJU Int. 2008;101:20–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xia G, Kumar S, Hawes D, Cai J, Hassanieh L, Groshen S, et al. Expression and Significance of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 2 in Bladder Cancer. J Urol. 2006;175:1245–52. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00736-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inoue K, Slaton J, Davis D, Hicklin D, McConkey D, Karashima T, et al. Treatment of human metastatic transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder in a murine model with the anti-vascular endothelial growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody DC101 and paclitaxel. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2635–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Osai W, Ng C, Pagliaro L. Positive response to bevacizumab in a patient with metastatic, chemotherapy-refractory urothelial carcinoma. Anticancer Drugs. 2008;19:427–9. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e3282f52bef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hahn O, Stadler W. Sorafenib. Current Opin Oncol. 2006;18:615–21. doi: 10.1097/01.cco.0000245316.82391.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler W, Szczylik C, Oudard S, Siebels M, et al. TARGET Study Group Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:125–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Llovet J, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc J, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–81. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bajorin D, Dodd P, Mazumdar M, Fazzari M, McCaffrey J, Scher H, et al. Long-term survival in metastatic transitional cell carcinoma and prognostic factors predicting outcome of therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3173–81. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.10.3173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bellmunt J, von der Maase H, Theodore C, Demkov T, Komyakow B, Sengelov L, et al. Randomised phase III trial of vinflunine (V) plus best supportive care (B) vs B alone as 2nd line therapy after a platinum-containing regimen in advanced transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelium (TCCU) J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(May 20 suppl) abstr 5028. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hussain M, MacVicar G, Petrylak D, Dunn R, Vaishampayan U, Lara P, et al. Trastuzumab, Paclitaxel, Carboplatin, and Gemcitabine in Advanced Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-2/neu–Positive Urothelial Carcinoma: Results of a Multicenter Phase II National Cancer Institute Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2218–24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.0994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lipponen P, Eskelinen M. Expression of epidermal growth factor receptor in bladder cancer as related to established prognostic factors, oncoprotein (c-erbB-2, p53) expression and long-term prognosis. Br J Cancer. 1994;69:1120–25. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petrylak D, Faulkner J, Van Veldhuizen P, Mansukhani M, Crawford E. Evaluation of ZD1839 for advanced transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) of the urothelium: a Southwest Oncology Group Trial. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2005;22:403. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gallagher D, Milowsky M, Gerst S, Iasonos A, Boyle M, Trout A, et al. Final results of a phase II study of sunitinib in patients (pts) with relapsed or refractory urothelial carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26 abstr 5082. [Google Scholar]