Abstract

Background and objectives: In clinical practice, physicians often use once-weekly (QW) and biweekly (Q2W) dosing of epoetin alfa to treat anemia in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Although the literature supports this practice, previous studies were limited by short treatment duration, lack of randomization, or absence of the approved three times per week (TIW) dosing arm. This randomized trial evaluated extended dosing regimens of epoetin alfa, comparing QW and Q2W to TIW dosing in anemic CKD subjects. The primary objective was to show that treatment with epoetin alfa at QW and Q2W intervals was not inferior to TIW dosing.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: 375 subjects with stage 3 to 4 CKD were randomized equally to the three groups and treated for 44 wk; to explore the impact of changing from TIW to QW administration on hemoglobin (Hb) control and adverse events, subjects on TIW switched to QW after 22 wk. The Hb was measured weekly, and the dose of epoetin alfa was adjusted to achieve and maintain an Hb level of 11.0 to 11.9 g/dl.

Results: Both the QW and Q2W regimens met the primary efficacy endpoint. More subjects in the TIW group than in the QW and Q2W groups exceeded the Hb ceiling. Adverse events were similar across treatment groups and consistent with the morbidities of CKD patients.

Conclusions: Administration of epoetin alfa at QW and Q2W intervals are potential alternatives to TIW dosing for the treatment of anemia in stage 3 to 4 CKD subjects.

Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) frequently develop anemia secondary to diminished erythropoietin production by the kidneys (1). Anemia of CKD is associated with decreased oxygen delivery and utilization, ventricular hypertrophy, congestive heart failure, and decreased cognition and mental acuity (2–6). Correction of anemia has been shown to improve exercise capacity, health-related quality of life, and cognition, and it may slow the progression of renal disease (7–10). Since their development, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) have become the standard of care for the treatment of patients with anemia associated with CKD (10,11). Epoetin alfa is an ESA with an amino acid sequence identical to endogenous human erythropoietin (12).

The approved starting dose of epoetin alfa for correction of anemia of CKD in adults is 50 to 100 IU/kg three times per week (TIW). For maintenance of hemoglobin (Hb) levels, the dosage of epoetin alfa is individualized to maintain the Hb within the target range of 11 to 12 g/dl (13) or between 10 and 12 g/dl (14). When administered subcutaneously, the serum half-life of epoetin alfa ranges from 28 to 43 h (12). However, the pharmacodynamic effect, as measured by an increase in red blood cell count, is evident for weeks to months. This reflects the life span (up to 120 d) of the red blood cells produced in response to ESA administration. In support of this concept, several studies in patients with CKD have reported that epoetin alfa administered (subcutaneously) up to every 4 wk can achieve and maintain Hb levels within a specified target range (15–21). In clinical practice, physicians often use once-weekly (QW) and biweekly (Q2W) dosing intervals in this patient population. These data suggest that dosing of epoetin alfa at extended intervals may be a potential treatment option. Nonetheless, to date, no randomized study of epoetin alfa has been conducted to compare extended dosing regimens to the approved TIW dosing regimen.

Extending the intervals between doses would be expected to provide significant benefits to patients by decreasing the frequency of injections, reducing the time spent in clinics/offices, increasing lifestyle flexibility with regard to travel and vacations, and potentially improving compliance. Furthermore, administration of epoetin alfa at extended intervals would decrease the utilization of healthcare services.

The purpose of this study was to test the hypothesis that extended dosing regimens of epoetin alfa, administered QW or Q2W, would be as safe and effective as the FDA-approved TIW regimen for treatment of anemia in subjects with CKD.

Materials and Methods

Study Conduct

This was a randomized, open-label, multicenter study conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonization, and the Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice at 77 centers in the United States between August 2006 and February 2008. The study protocol and amendments were reviewed and approved by an Institutional Review Board, and subjects provided their written consent to participate in the study.

Study Population

The study population was comprised of subjects ≥18 yr of age with CKD (defined as GFR ≥15 and <60 ml/min/1.73 m2) who required support of an ESA for one of the following reasons: no prior ESA therapy and Hb <10.5 g/dl; no prior ESA therapy and Hb <11.0 g/dl with a documented ≥1 g/dl Hb decrease within the past 12 mo; or no ESA therapy within 2 mo before screening, resulting in a documented ≥1 g/dl Hb decrease since stopping ESA therapy and Hb <11.0 g/dl.

Key exclusion criteria included iron deficiency, with serum ferritin concentration <50 ng/ml and transferrin saturation <20%; poorly controlled hypertension (systolic BP >160 mmHg or diastolic BP >100 mmHg); severe congestive heart failure or coronary artery disease; active infection or inflammation that could affect the response to epoetin alfa therapy; uncontrolled or new onset of seizures; deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolus within the prior 12 mo; stroke, transient ischemic attack, acute coronary syndrome, or other arterial thrombosis within the prior 6 mo; and requiring dialysis or anticipated to require dialysis during the study.

Study Design

The study was 48 to 50 wk in duration and had three phases: screening phase of up to 2 wk, 44-wk open-label treatment phase (which consisted of a 22-wk initiation and maintenance period followed by a 22-wk safety period), and 4-wk post-treatment phase. Eligible subjects were randomly assigned to one of three treatment groups in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive epoetin alfa (Procrit; Ortho Biotech Products, Raritan, NJ) at an initial dose of 50 IU/kg subcutaneously TIW, 10,000 IU subcutaneously QW, or 20,000 IU subcutaneously Q2W. To make the initial doses comparable in all three treatment groups, the starting QW and Q2W doses were based on the weekly dose required by a 70-kg subject on a TIW regimen. Open-label treatment continued for a total of 44 wk. After completion of the 22-wk initiation and maintenance period to evaluate efficacy, subjects randomly assigned to the TIW group were switched at week 23 to an initial dose of 10,000 IU subcutaneously QW. Subjects in the QW and Q2W groups continued their assigned treatment.

Study drug was withheld if the Hb exceeded 11.9 g/dl or if the Hb rate of rise was ≥1.5 g/dl in the prior 2 wk. The dose was reduced if the Hb rate of rise was ≥1.0 but <1.5 g/dl in the prior 2 wk, and the dose was increased if the Hb level was ≤10.5 g/dl with a Hb rate of rise of <0.5 g/dl in the prior 2 wk. Dose reductions and increases were calculated in aliquots of 25% of the subject's initial dose. After week 23, dose adjustments for subjects assigned to the TIW group were based on the 10,000-IU dose. Dose increases were not permitted in the first 4 wk of study drug administration. There was a minimum of 4 wk between repeated dose increases or dose reductions.

Iron therapy was strongly recommended to keep the transferrin saturation (TSAT) >20%. The TSAT and serum ferritin were measured at screening and every 4 wk while on study. Oral iron supplements were provided to the investigators for distribution to the subjects. Treatment with parenteral iron was permitted.

Assessments

Venous blood samples were collected at the study site at screening and weekly thereafter through week 45. The Hb values were measured by the HemoCue Hb 201+ System or at a local laboratory. Transfusion information was recorded from screening through week 45.

The following safety parameters were assessed weekly: adverse effects (AEs), including serious adverse effects (SAEs), thrombotic vascular events (TVEs), and hypertension, and vital sign measurements. Physical examinations were conducted, and serum erythropoietin antibodies were measured at screening, the completion/early withdrawal visit, the predialysis visit, and in the evaluation of an unexpected decrease in Hb levels. Clinical laboratory parameters were measured every 4 wk.

Study Endpoints

The primary efficacy endpoint of the study was the change in Hb from baseline to the average of the Hb values over the last 8 wk of treatment through week 22. A prespecified noninferiority margin of −1 g/dl was selected to exclude a clinically relevant difference between the treatment groups. The secondary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of subjects with a ≥1 g/dl increase in Hb level from baseline by week 9.

Statistical Analyses

It was estimated that a sample size of approximately 375 subjects (125 per group) would provide 90% power to show that the test-treatment groups (QW and Q2W groups) were noninferior to the standard treatment group (TIW group) for an overall two-sided 0.05 significance level.

Primary and secondary efficacy endpoints were analyzed using the modified intent to treat (mITT) population (defined as all randomized subjects who had at least one postrandomization Hb measurement) and safety endpoints were analyzed using the safety population (defined as all randomized subjects who received at least one injection of study drug). The per-protocol population was defined as all randomized subjects who received ≥75% of the intended doses during the first 22 wk before withdrawal from the study, receipt of a transfusion, or initiation of dialysis, whichever occurred earliest, and who had no major protocol violations. The per-protocol population was used in a sensitivity analysis for all efficacy and the Hb-related safety endpoints.

For comparisons of the mean change in Hb from baseline to the average of the last 8 wk of treatment through week 22 between the TIW and QW groups and between the TIW and Q2W groups, an estimate of the difference in the mean changes (QW minus TIW and Q2W minus TIW) was computed along with the two-sided 95% confidence interval (CI) for the difference. The estimates of the difference and the CI were calculated using an analysis of covariance, including baseline Hb as a covariate or both study center and baseline Hb as covariates. The two comparisons were tested in a stepdown manner. First, QW dosing was declared noninferior to TIW dosing if the lower limit of the CI for the difference was greater than –1 g/dl. If QW was found to be noninferior to TIW, Q2W was tested against TIW. If the CI for the difference for the Q2W minus the TIW was greater than –1 g/dl, Q2W was declared noninferior to TIW.

Comparisons between the TIW and QW and between the TIW and Q2W dosing groups in proportion of subjects with an increase in Hb from baseline of ≥1 g/dl by week 9 and proportion of subjects who exceeded a Hb level of 11.9 g/dl during the first 22 wk of treatment were performed by computing an estimate of the difference in proportions (QW minus TIW and Q2W minus TIW) along with the two-sided 95% CI for the difference. The same treatment comparisons in per-subject frequency of exceeding Hb of 11.9 g/dl were performed using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test.

Results

Baseline Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

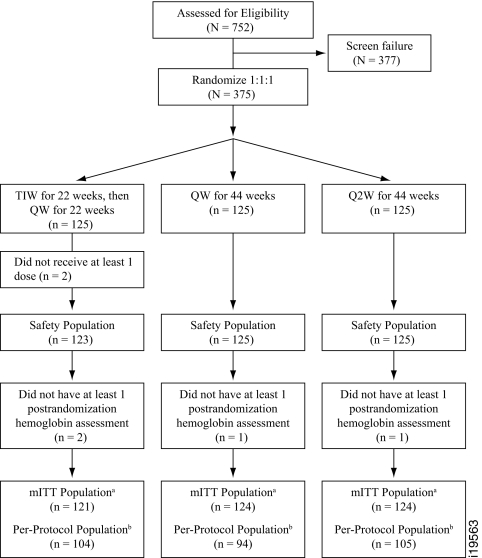

Subjects were randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio to one of three treatment groups: TIW, QW, and Q2W (Figure 1). Demographic and baseline characteristics were generally well balanced among the three treatment groups (Table 1). Overall mean baseline estimated GFR (eGFR) was approximately 30 ml/min. Mean baseline Hb levels were 9.6, 9.7, and 9.8 g/dl for the TIW, QW, and Q2W groups, respectively.

Figure 1.

Patient disposition and study schema. TIW, three times per week; QW, once weekly; Q2W, biweekly; Hb, hemoglobin; mITT, modified intent to treat. amITT population: subjects who were randomized and had at least one postrandomization Hb value. bPer-protocol population: subjects who received at least 75% of the intended doses during the first 22 wk of the study (i.e., at least 50 doses for the TIW group, at least 17 doses for the QW group, and at least 9 doses for the TIW group) before withdrawal from the study, receipt of a transfusion, or initiation of dialysis, whichever occurred earliest, and who had no major protocol deviations.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics (modified intent-to-treat population analysis set)

| TIW(n = 121) | QW(n = 124) | Q2W(n = 124) | Total(n = 369) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 71.4 (12.88) | 68.8 (11.89) | 69.0 (13.04) | 69.7 (12.63) |

| Range | (33–94) | (37–95) | (30–101) | (30–101) |

| Sex [n (%)] | ||||

| Male | 45 (37.2) | 45 (36.3) | 39 (31.5) | 129 (35.0) |

| Female | 76 (62.8) | 79 (63.7) | 85 (68.5) | 240 (65.0) |

| Race [n (%)] | ||||

| White | 67 (55.4) | 64 (51.6) | 64 (51.6) | 195 (52.8) |

| Black | 42 (34.7) | 44 (35.5) | 41 (33.1) | 127 (34.4) |

| Asian | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 5 (4.0) | 6 (1.6) |

| Other | 12 (9.9) | 15 (12.1) | 14 (11.3) | 41 (11.1) |

| Baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate (ml/min) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 30.68 (11.075) | 29.81 (11.175) | 29.49 (10.224) | 29.98 (10.812) |

| Range | (15.0–71.0) | (15.0–59.0) | (15.0–56.0) | (15.0–71.0) |

| Baseline hemoglobin (g/dl) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 9.63 (0.861) | 9.71 (0.735) | 9.81 (0.748) | 9.72 (0.784) |

| Median | 9.70 | 9.80 | 10.00 | 9.90 |

| Range | (7.3–12.0) | (8.1–10.9) | (7.0–10.9) | (7.0–12.0) |

| Baseline ferritin level (pmol/L) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 510.23 (376.686) | 573.81 (468.852) | 552.74 (439.828) | 545.98 (430.362) |

| Range | (33.0–1670) | (46.0–2187) | (26.0–2004) | (26.0–2187) |

| Primary cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD) [n (%)]a | ||||

| Total no. subjects with known CKDb | 123 (100) | 125 (100) | 123 (98) | 371 (99) |

| Diabetes | 68 (55) | 79 (63) | 72 (58) | 219 (59) |

| Hypertension | 88 (72) | 89 (71) | 80 (64) | 257 (69) |

| Glomerulonephritis | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 5 (4) | 11 (3) |

| Renal vascular disease | 10 (8) | 2 (2) | 6 (5) | 18 (5) |

| Interstitial nephritis | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 5 (1) |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Obstructive nephropathy | 4 (3) | 0 | 1 (1) | 5 (1) |

| Renal failure caused by metabolic disease | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 5 (1) |

| Toxic nephropathy | 2 (2) | 0 | 1 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Other | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 5 (4) | 9 (2) |

Percentages calculated with the number of subjects in each group as denominator.

Data based on safety population.

Two subjects in the Q2W group had unknown underlying causes of CKD.

Q2W, every 2 wk; QW, once weekly; TIW, three times weekly.

Epoetin Alfa Dose

The mean weekly epoetin alfa doses were 5039 ± 2772 IU, 5035 ± 2449 IU, and 6662 ± 2938 IU, and the median weekly doses were 4382, 4364, and 6091 IU for the TIW, QW, and Q2W groups, respectively. Dose increases were uncommon during the first 22 wk of treatment and comparable across the three treatment groups. However, dose decreases and dose holds were more frequent in the TIW dosing group compared with the QW and Q2W groups.

Mean Change in Hb from Baseline

Both the QW and Q2W epoetin alfa dosing regimens were noninferior to the TIW dosing regimen with respect to the change in Hb from baseline to the average of the last 8 wk of treatment through week 22. The lower limit of the 95% CI for the estimated treatment difference for both comparisons—QW versus TIW and Q2W versus TIW—was above the prespecified noninferiority margin of –1 g/dl (Table 2). The results were similar when baseline Hb and study center (sites with two or fewer subjects were pooled) were used as covariates.

Table 2.

Change in hemoglobin (g/dl) from baseline to the average of the last 8 wk of treatment through week 22 excluding data collected after dialysis (modified intent-to-treat analysis set)

| TIW(n = 121) | QW(n = 124) | Q2W(n = 124) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 121 | 124 | 123 |

| Mean baseline | 9.63 | 9.71 | 9.82 |

| Mean change (SD) (minus TIW) | 1.81 (0.910) | 1.59 (0.997) | 1.27 (0.906) |

| Diff. of LS means (SE) | −0.17 (0.106) | −0.43 (0.107) | |

| 95% CI | (−0.380; 0.037) | (−0.641; −0.221) |

ANCOVA model with baseline hemoglobin alone as covariate.

CI, confidence interval; Diff., difference; LS, least squares; Q2W, every 2 wk; QW, once weekly; TIW, three times weekly.

These results seem to be robust, because sensitivity analyses based on the per-protocol population and ANCOVA models adjusted for both baseline Hb level and study center showed similar findings.

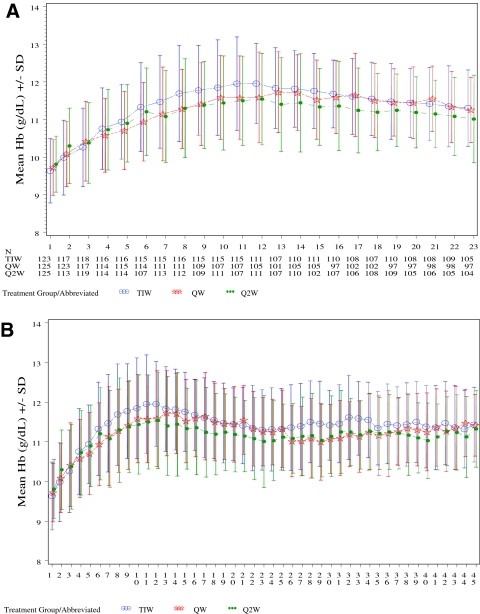

Hematologic Response

Hemoglobin levels over time are shown in Figure 2, A and B. By week 9, the vast majority of subjects in each treatment group achieved a ≥1 g/dl Hb increase (96, 87, and 86% for the TIW, QW, and Q2W groups, respectively; mITT population). By week 23, nearly all subjects achieved a ≥1 g/dl Hb increase (98, 93, and 93% in the TIW, QW, and Q2W groups, respectively) and an Hb ≥11.0 g/dl (97, 90, and 90%, respectively). Mean final Hb levels by week 23 were within the range of 11.0 to 11.9 g/dl in all treatment groups (11.4, 11.3, and 11.1 g/dl in the TIW, QW, and Q2W groups, respectively). The mean ± SD weekly Hb concentrations for subjects in the TIW/QW group were comparable before (11.51 ± 0.82 g/dl) and after (11.44 ± 0.79 g/dl) the transition from TIW to QW dosing.

Figure 2.

Mean Hb over the first 22 (A) and 44 wk (B) of treatment by epoetin alfa treatment groups. TIW, three times weekly; QW, once weekly; Q2W, biweekly.

Red Blood Cell Transfusions

During the first 22 wk of treatment, 15 (4.1%) subjects received red blood cell transfusions (0.8, 4.0, and 7.3% in the TIW, QW, and Q2W groups, respectively). Over the 44-wk treatment period, 24 (6.5%) subjects received transfusions (2.5% in the TIW/QW group, 6.5% in the QW group, and 10.5% in the Q2W group). The majority (19 subjects) received transfusions for anemia that developed while hospitalized for an intercurrent medical event or surgical procedure. Of the remaining five subjects, three (in the Q2W group) were transfused after receiving one or two doses of epoetin alfa, before the time that an increase in Hb level caused by study drug would be expected.

Iron Supplementation

The number of subjects who received iron supplementation was comparable in the three treatment groups (112 in the TIW, 105 in the QW, and 113 in the Q2W groups). The serum ferritin and TSAT at baseline and at the completion of the first 22 wk of treatment were also comparable among the three groups.

Safety

The proportion of subjects who exceeded an Hb level of 11.9 g/dl (the threshold for withholding a dose) during the first 22 wk of treatment was higher in the TIW group (86.2%) than the QW (78.4%) and Q2W (71.2%) groups. In addition, subjects in the TIW group exceeded the Hb threshold of 11.9 g/dl more often (six times) than those in the QW (four times) or Q2W (three times) groups. There were no differences in the proportions of subjects meeting or exceeding Hb rates of rise of 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 g/dl per 2 wk among the three groups.

The incidence of reported AEs was comparable among the three treatment groups (Table 3). Discontinuation from the study because of an AE was low: 1, 1, and 2% over the first 22 wk and 2, 2, and 4% over the 44-wk treatment period in the TIW/QW, QW, and Q2W groups, respectively. The incidence of AEs was comparable during the transition from TIW to QW dosing.

Table 3.

Treatment-emergent adverse events during the study excluding data collected after dialysis (safety population analysis set)

| Events | TIW(n = 123)[n (%)] | QW(n = 125)[n (%)] | Q2W(n = 125)[n (%)] | Total(n = 373)[n (%)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| During the first 22 wk of treatment | ||||

| Subjects with adverse events | 83 (68) | 83 (66) | 95 (76) | 261 (70) |

| Subjects with drug-related adverse eventsa | 10 (8) | 8 (6) | 6 (5) | 24 (6) |

| Subjects with serious adverse events | 19 (15) | 27 (22) | 28 (22) | 74 (20) |

| Subjects with confirmed thromboembolic vascular events | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 3 (2) | 7 (2) |

| Subjects with hypertension | 14 (11) | 11 (9) | 6 (5) | 31 (8) |

| Subjects with adverse events leading to study discontinuation | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 4 (1) |

| Subjects who died | 0 (0) | 6 (5) | 3 (2) | 9 (2) |

| During the entire 44-wk treatment period | ||||

| Subjects with adverse events | 98 (80) | 98 (78) | 107 (86) | 303 (81) |

| Subjects with drug-related adverse eventsa | 11 (9) | 11 (9) | 15 (12) | 37 (10) |

| Subjects with serious adverse events | 36 (29) | 41 (33) | 42 (34) | 119 (32) |

| Subjects with confirmed thromboembolic vascular events | 2 (2) | 5 (4) | 8 (6) | 15 (4) |

| Subjects with hypertension | 16 (13) | 18 (14) | 12 (10) | 46 (12) |

| Subjects with adverse events leading to study discontinuation | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 5 (4) | 11 (3) |

| Subjects who died | 4 (3) | 6 (5) | 4 (3) | 14 (4) |

Treatment-emergent adverse events defined as all adverse events that occurred after the first dose of study drug. Incidence is based on the number of subjects experiencing at least one adverse event and not the number of events. Adverse events that occurred on the same day as the initiation of dialysis were determined to have occurred before dialysis.

Drug-related adverse events defined as possible, probable, or very likely related to study drug.

Q2W, every 2 wk; QW, once weekly; TIW, three times weekly.

The incidence of treatment-emergent SAEs during the first 22 wk of treatment was 20%, with a lower rate (15%) among subjects in the TIW group compared with the QW (22%) and Q2W (22%) groups. The most commonly reported SAEs during the first 22 wk of treatment were congestive heart failure (2%) and chronic renal failure (2%). The incidence of SAEs over the entire 44-wk treatment period was 29% in the TIW/QW group, 33% in the QW group, and 34% in the Q2W group (Table 4). No clear relationship was observed between mean weekly Hb level and number of SAEs by week for any of the three treatment groups.

Table 4.

Incidence of treatment-emergent serious adverse events during the entire 44-wk treatment period in at least 2% of subjects in any treatment group by MedDRA preferred term excluding data collected after dialysis (safety population analysis set)

| TIW(n = 123)[n (%)] | QW(n = 125)[n (%)] | Q2W(n = 125)[n (%)] | Total(n = 373)[n (%)] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. subjects with serious adverse events | 36 (29) | 41 (33) | 42 (34) | 119 (32) |

| Cardiac failure congestive | 4 (3) | 4 (3) | 6 (5) | 14 (4) |

| Renal failure chronic | 4 (3) | 3 (2) | 5 (4) | 12 (3) |

| Hypoglycemia | 5 (4) | 4 (3) | 0 | 9 (2) |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 | 2 (2) | 5 (4) | 7 (2) |

| Renal failure acute | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 3 (2) | 7 (2) |

| Pneumonia | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 6 (2) |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 5 (1) |

| Hip fracture | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 5 (1) |

| Dehydration | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 4 (1) |

| Syncope | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 4 (1) |

| Urinary tract infection | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 4 (1) |

| Anemia | 0 | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Chest pain | 0 | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 1 (1) | 0 | 2 (2) | 3 (1) |

| Dyspnea | 0 | 0 | 3 (2) | 3 (1) |

| Fall | 0 | 0 | 3 (2) | 3 (1) |

| Diarrhea | 0 | 0 | 2 (2) | 2 (1) |

| Osteoarthritis | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | 2 (1) |

| Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 0 | 2 (2) | 0 | 2 (1) |

Incidence is based on the number of subjects experiencing at least one serious adverse event and not the number of events. SAEs within 30 days of the last dose were included. Adverse events that occurred on the same day as the initiation of dialysis were determined to have occurred before dialysis.

MedDRA, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities; Q2W, every 2 wk; QW, once weekly; TIW, three times weekly

The incidence of subjects starting dialysis during the first 22 wk of treatment was 2.4% for the TIW group, 1.6% for the QW group, and 2.4% for the Q2W group. Over the course of the 44-wk treatment period, the incidence of subjects starting dialysis was 6.5% for the TIW/QW group, 4.8% for the QW group, and 8.8% for the Q2W group.

The number of subjects with TVEs confirmed by a diagnostic evaluation was low across the three treatment groups (Table 5). No clear relationship was observed between mean weekly Hb level and number of TVEs by week for any of the three treatment groups.

Table 5.

Incidence of treatment-emergent confirmed thromboembolic vascular events excluding data collected after dialysis (safety population analysis set)

| TIW(n = 123)[n (%)] | QW(n = 125)[n (%)] | Q2W(n = 125)[n (%)] | Total(n = 373)[n (%)] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| During the first 22 wk of treatment | ||||

| Total no. subjects with TVE | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 3 (2) | 7 (2) |

| Stroke | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Other arterial thrombosis/embolism | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (<1) |

| During the entire 44-wk treatment period | ||||

| Total no. subjects with TVE | 2 (2) | 5 (4) | 8 (6) | 15 (4) |

| Stroke | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 4 (1) |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 0 | 3 (2) | 4 (3) | 7 (2) |

| Other arterial thrombosis/embolism | 0 | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

Incidence is based on the number of subjects experiencing at least one TVE and not the number of events. TVEs within 30 days of the last dose were included. Adverse events that occurred on the same day as the initiation of dialysis were determined to have occurred before dialysis.

During the first 22 wk of treatment, the incidence of new onset or exacerbation of hypertension was higher in the TIW group (11%) compared with the QW group (9%) and the Q2W group (5%). Treatment-emergent hypertension in the TIW group tended to occur by week 9. Over the 44-wk treatment period, the incidence of treatment-emergent hypertension was similar for the three treatment groups: 13, 14, and 10% for the TIW/QW, QW, and Q2W groups, respectively.

In the first 22 wk of treatment, there were zero (0%), six (5%), and three (2%) deaths in the TIW, QW, and Q2W dosing groups, respectively. There were 14 (4%) subjects who died during the study: 4 (3%) in the TIW/QW group, 6 (5%) in the QW group, and 4 (3%) in the Q2W group. The individual subject causes of death are listed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Incidence and causes of mortality

| TIW(n = 123)[n (%)] | QW(n = 125)[n (%)] | Q2W(n = 125)[n (%)] | Total(n = 373)[n (%)] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| During first 22 wk of treatment | ||||

| Total no. subjects who died | 0 | 6 (5) | 3 (2) | 9 (2) |

| Cause of death | ||||

| Cardiac arrest | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (<1) |

| Death related to septic shock | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (<1) |

| Pulmonary cardiac arrest | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (<1) |

| Respiratory distress | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (<1) |

| Respiratory failure | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (<1) |

| Sepsis | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (<1) |

| Shortness of breath | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (<1) |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (<1) |

| Suspected arrhythmias | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (<1) |

| During the entire 44-wk treatment period | ||||

| Total no. subjects who died | 4 (3) | 6 (5) | 4 (3) | 14 (4) |

| Cause of death | ||||

| Sepsis | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 2 (1) |

| Advanced metastatic prostate cancer | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (<1) |

| Cardiac arrest | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (<1) |

| Death related to septic shock | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (<1) |

| Diabetic complications | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (<1) |

| Pulmonary cardiac arrest | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (<1) |

| Respiratory distress | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (<1) |

| Respiratory failure | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (<1) |

| Respiratory failure from asthma | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (<1) |

| Shortness of breath | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (<1) |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (<1) |

| Suspected arrhythmias | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (<1) |

| Unknown | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (<1) |

Percentages calculated with the number of subjects in each group as denominator. SAEs resulting in death within 30 days of the last dose were included.

n, number; Q2W, every 2 wk; QW, once weekly; TIW, three times weekly.

Over the entire study, no subject had a positive test for epoetin antibody, and no subject underwent a renal transplantation.

Discussion

This randomized, controlled study showed that both the QW and Q2W extended dosing regimens of epoetin alfa were noninferior to the TIW dosing regimen with respect to the mean change in Hb from baseline to the final Hb and confirmed the results of previous studies of extended dosing of epoetin alfa for correction of anemia and maintenance of Hb in the CKD patient population (15,17,19–21). In addition, the proportion of subjects with ≥1g/dl Hb increase and Hb ≥11.0 g/dl were comparable among the groups. Overall, the number of subjects transfused was low, but higher in the extended dosing groups. However, most of the transfusions were administered during hospitalizations for intercurrent medical conditions or surgical procedures.

The incidence of AEs, SAEs, and hypertension was generally similar in the TIW/QW, QW, and Q2W treatment groups over the duration of the study. Given the baseline level of kidney function, the incidence of subjects starting dialysis during the study was low. Few subjects were discontinued from the study because of an AE. Considering the age and comorbidities of the subjects, the occurrence of TVEs and deaths over the 44-wk treatment period was low.

An increased risk of TVEs has been reported in some patient populations treated with ESAs (22,23), most notably in oncology patients and in patients undergoing surgical procedures. In this study, the incidence of TVEs was low, despite the fact that these subjects had multiple pre-existing risk factors (age, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, obesity, and prior history of vascular events). The incidence of TVEs was distributed across the dosing groups and did not seem to be related to Hb level, Hb rate of rise, epoetin alfa dose, or dosing interval, although the small sample size and number of events preclude making any definitive conclusions.

This study showed that Hb levels rose at a somewhat slower rate and were less likely to exceed the Hb ceiling in the QW and Q2W treatment groups compared with the standard TIW treatment. The dose required to maintain Hb in the Q2W group was higher, 35% in relative terms and approximately 1700 IU in absolute terms. This increase in dose is relatively modest and remains within the labeled TIW treatment dose range. Balanced against the modest increase in additional dose are the substantial benefits for patients—decreased frequency of injections, greater flexibility for travel with less need to carry medication and needles and syringes, less medical waste, and possibly fewer clinic/provider visits. There was no meaningful difference in the three treatment groups with regard to the mean final Hb or the proportion of subjects who had a ≥1 g/dl increase in Hb or a Hb ≥11.0 g/dl, consistent with published data (15,19,20). Taken together, these studies support QW and Q2W dosing of epoetin alfa to achieve and maintain Hb levels within the targeted therapeutic range of 11.0 to 11.9 g/dl.

In conclusion, the results of this study showed that QW and Q2W extended dosing regimens of epoetin alfa are potential alternatives to TIW dosing for the treatment of anemia in subjects with stage 3 to 4 CKD.

Disclosures

G.G., M.F., S.R., and P.B. are employees of Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development and own stock in Johnson & Johnson. M.W. is an employee of Centocor Ortho Biotech Services and owns stock in Johnson & Johnson. P.P. has received research support from Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development.

Acknowledgments

We thank Denise Okonsky for assistance with the conduct of the study, Agnes Li for data programming, and Namit Ghildyal for assistance in the preparation of the manuscript. This work was supported by Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development. The protocol registration number of this study at ClinicalTrials.gov is NCT00440557. Results from this study were presented in part at the American Society of Nephrology Renal Week, Philadelphia, PA, November 4–9, 2008.

Appendix: Study Investigators

The following investigators (listed in alphabetical order) participated in the EPO-AKD-3001 study: L. Abbott, MD, Nephrology Consultants, Orlando, FL; A. Ackad, MD, Bergen Hypertension and Renal Associates, Hackensack, NJ; I. Aisiku, MD, Medical Research Initiatives, Richmond, VA; M. Akmal, MD, DaVita/USC Kidney Center, Los Angeles, CA; S. Arfeen, MD, Nephrology Specialists, PC, Michigan City, IN; A. Ashfaq, MD, North Shore University Hospital Division of Nephrology & Hypertension, Great Neck, NY; C. Atekha, MD, Atekha Nephrology Clinic, Statesboro, GA; O. Ayodeji, MD, MPH, Peninsula Kidney Associates, Hampton, VA; K. Barber, DO, Cumberland Nephrology Associates, Vineland, NJ; D. Belo, MD, CA Institute of Renal Research, Chula Vista, CA; R. Benz, MD, Nephrology Associates Lankenau Hospital, Wynnewood, PA; M. Bernardo, MD, Southwest Houston Research, Ltd., Houston, TX; S. Bhalla, MD, Southwest Kidney Institute, PLC, Tempe, AZ; P. Chidester, MD, Tidewater Kidney Specialists, Chesapeake, VA; C. Christiano, MD, East Carolina University Nephrology and Hypertension, Greenville, NC; E. Clark, MD, Regional Kidney Disease Center, Erie, PA; N. Daboul, MD, Advanced Medical Research, Maumee, OH; G. Dubov, MD, Nephrology Hypertension Associates of Central Jersey, South River, NJ; F. Dumenigo, MD, Research Center of Florida, Inc., Miami, FL; M. El-Shahawy, MD, Academic Medical Research Institute, Inc., Los Angeles, CA; G. Fadda, MD, CA Institute of Renal Research, San Diego, CA; E. Galindo-Ramos, MD, Fresenius Medical Care-PR, Caguas, PR; R. Gaona Jr., MD, Quality Assurance Research Center, San Antonio, TX; D. Gillum, MD, Western Nephrology and Metabolic Bone Disease, PC, Lakewood, CO; D. Goodman, MD, Slocum-Dickson Medical Group, PLLC, New Hartford, NY; T. Griffith, MD, Metrolina Nephrology Associates, PA, Charlotte, NC; R. Haley, MD, Renal Medical Group, Visalia, CA; R. Halligan, MD, Bayview Nephrology, Erie, PA; S. Handelsman, MD, North Atlanta Kidney Specialists, PC Atlanta, GA; S. Hood, MD, Merrimack Valley Nephrology, Pentucket Medical Associates, Methuen, MA; J. Joshi, MD, Summit Medical Clinic, Colorado Springs, CO; M. Kang, MD, Southwest Kidney Institute, PLC, Glendale, AZ; G. Keightley, MD, Nephrology Specialists, PC, Richmond, VA; S. Khwaja, MD, Renal Medical Associates, Lynwood, CA; V. Kondle, MD, North Valley Nephrology, Yuba City, CA; P. Lazowski, MD, Plymouth, MA; J. Lee, MD, Apex Research of Riverside, Riverside, CA; V. Lorica, MD, Clinical Research and Consulting Center, LLC, Fairfax, VA; E. Martin, MD, South Florida Research Institute, Lauderdale Lakes, FL; C. Martinez, MD, Renal Physicians of Georgia, PC, Macon, GA; K. McConnell, MD, Jefferson Nephrology, Ltd., Charlottesville, VA; R. Mehrotra, MD, Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor - UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA; A. Mehta, MD, Shreenath Clinical Services, Long Beach, CA; B. Mehta, MD, Arlington Nephrology, PA, Arlington, TX; I. Meisels, MD, St. Luke's-Roosevelt Hospital, New York, NY; J. Mersey, MD, Model Clinical Research, Baltimore, MD; A. Mohammed, MD, Hurley Research Center, Flint, MI; M. Moustafa, MD, SC Nephrology & Hypertension Center, Inc., Orangeburg, SC; R. Mulay, MD, Medical Nephrology Associates, Dyersburg, TN; M. Nassri, MD, Palmetto Nephrology, Orangeburg, SC; J. Navarro, MD, Genesis Clinical Research, Tampa, FL; A. Nossuli, MD, Bethesda, MD; M. Orig, MD, Carroll County Nephrology, Carrollton, GA; V. Patel, MD, FL Medical Clinic Nephrology Division, Zephyrhills, FL; P. Pergola, MD, PhD, Renal Associates, PA, San Antonio, TX; R. Pursell, MD, Lehigh Valley Nephrology Associates, Easton, PA; D. Raj, MD, University of New Mexico Health Science Center, Albuquerque, NM; R. Ranjan, MD, VA Western NY Healthcare System, Buffalo, NY; J. Regimbal, MD, Internal Medicine Northwest, Tacoma, WA; C. Rodenberger, MD, Hypertension and Kidney Specialists, Lancaster, PA; S. Sader, MD, RenalCare Associates, Peoria, IL; R. Sarin, MD, Ball Memorial Hospital, Muncie, IN; D. Scott, MD, Clinical Research Development Associates, LLC, Springfield Gardens, NY; M. Smith, MD, Nephrology Associates, PC, Augusta, GA; P. Suchinda, MD, Carolina Diabetes and Kidney Center, Sumter, SC; J. Swan, MD, Clinical Research Associates, Palm Beach Gardens, FL; P. Turer, MD, Mid Atlantic Nephrology Associates, PA, Baltimore, MD; M. Vernace, MD, Nephrology Hypertension Specialists, Doylestown, PA; M. Waseem, MD, Baltimore, MD; R.Weiss, MD, West Palm Beach, FL.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Caveats for Scientific Publication in the Modern Marketplace,” on pages 1693–1695.

Access to UpToDate on-line is available for additional clinical information at http://www.cjasn.org/

References

- 1.Astor BC, Muntner P, Levin A, Eustace JA, Coresh J: Association of kidney function with anemia: The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1988–1994). Arch Intern Med 162: 1401– 1408, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teehan BP, Benz RL, Sigler MH, Brown JM: Early intervention with recombinant human erythropoietin therapy. Semin Nephrol 10: 28– 34, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levin A, Singer J, Thompson CR, Ross H, Lewis M: Prevalent left ventricular hypertrophy in the predialysis population: identifying opportunities for intervention. Am J Kidney Dis 27: 347– 354, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silverberg DS, Wexler D, Blum M, Keren G, Sheps D, Leibovitch E, Brosh D, Laniado S, Schwartz D, Yachnin T, Shapira I, Gavish D, Baruch R, Koifman B, Kaplan C, Steinbruch S, Iaina A: The use of subcutaneous erythropoietin and intravenous iron for the treatment of the anemia of severe, resistant congestive heart failure improves cardiac and renal function and functional cardiac class, and markedly reduces hospitalizations. J Am Coll Cardiol 35: 1737– 1744, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pickett JL, Theberge DC, Brown WS, Schweitzer SU, Nissenson AR: Normalizing hematocrit in dialysis patients improves brain function. Am J Kidney Dis 33: 1122– 1130, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McClellan W, Aronoff SL, Bolton WK, Hood S, Lorber DL, Tang KL, Tse TF, Wasserman B, Leiserowitz M: The prevalence of anemia in patients with chronic kidney disease. Curr Med Res Opin 20: 1501– 1510, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Revicki DA, Brown RE, Feeny DH, Henry D, Teehan BP, Rudnick MR, Benz RL: Health-related quality of life associated with recombinant human erythropoietin therapy for predialysis chronic renal disease patients. Am J Kidney Dis 25: 548– 554, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuriyama S, Tomonari H, Yoshida H, Hashimoto T, Kawaguchi Y, Sakai O: Reversal of anemia by erythropoietin therapy retards the progression of chronic renal failure, especially in nondiabetic patients. Nephron 77: 176– 185, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jungers P, Choukroun G, Oualim Z, Robino C, Nguyen AT, Man NK: Beneficial influence of recombinant human erythropoietin therapy on the rate of progression of chronic renal failure in predialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 16: 307– 312, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nissenson AR: Novel erythropoiesis stimulating protein for managing the anemia of chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 38: 1390– 1397, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maxwell AP: Novel erythropoiesis-stimulating protein in the management of the anemia of chronic renal failure. Kidney Int 62: 720– 729, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGowan T, Vaccaro NM, Beaver JS, Massarella J, Wolfson M: Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles of extended dosing of epoetin alfa in anemic patients who have chronic kidney disease and are not on dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 1006– 1014, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.K-DOQI Working Group Members: IV. NKF-K/DOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Anemia of Chronic Kidney Disease: Update 2000. Am J Kidney Dis 37: S182– S238, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.PROCRIT Prescribing Information [online]. Available at: www.procrit.com Accessed April 20, 2009

- 15.Spinowitz B, Germain M, Benz R, Wolfson M, McGowan T, Tang KL, Kamin M: A randomized study of extended dosing regimens for initiation of epoetin alfa treatment for anemia of chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 935– 937, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piccoli A, Malagoli A, Komninos G, Pastori G: Subcutaneous epoetin-alfa every one, two, and three weeks in renal anemia. J Nephrol 15: 565– 574, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Provenzano R, Bhaduri S, Singh AK, Group PS: Extended epoetin alfa dosing as maintenance treatment for the anemia of chronic kidney disease: the PROMPT study. Clin Nephrol 64: 113– 123, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim VS, Kirchner PT, Fangman J, Richmond J, DeGowin RL: The safety and the efficacy of maintenance therapy of recombinant human erythropoietin in patients with renal insufficiency. Am J Kidney Dis 14: 496– 506, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Provenzano R, Garcia-Mayol L, Suchinda P, Von Hartitzsch B, Woollen SB, Zabaneh R, Fink JC, Group PS: Once-weekly epoetin alfa for treating the anemia of chronic kidney disease. Clin Nephrol 61: 392– 405, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benz R, Schmidt R, Kelly K, Wolfson M: Epoetin alfa once every 2 weeks is effective for initiation of treatment of anemia of chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 215– 221, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Germain M, Ram CV, Bhaduri S, Tang KL, Klausner M, Curzi M: Extended epoetin alfa dosing in chronic kidney disease patients: A retrospective review. Nephrol Dialysis Transplant 20: 2146– 2152, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Locatelli F, Olivares J, Walker R, Wilkie M, Jenkins B, Dewey C, Gray SJ: Novel erythropoiesis stimulating protein for treatment of anemia in chronic renal insufficiency. Kidney Int 60: 741– 747, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Macdougall IC, Walker R, Provenzano R, de Alvaro F, Locay HR, Nader PC, Locatelli F, Dougherty FC, Beyer U: C.E.R.A. corrects anemia in patients with chronic kidney disease not on dialysis: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 337– 347, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]