Abstract

The intermediate filament (IF) protein nestin coassembles with vimentin and promotes the disassembly of these copolymers when vimentin is hyperphosphorylated during mitosis. The aim of this study is to determine the function of these nonfilamentous particles by identifying their interacting partners. In this study, we report that these disassembled vimentin/nestin complexes interact with insulin degrading enzyme (IDE). Both vimentin and nestin interact with IDE in vitro, but vimentin binds IDE with a higher affinity than nestin. Although the interaction between vimentin and IDE is enhanced by vimentin phosphorylation at Ser-55, the interaction between nestin and IDE is phosphorylation independent. Further analyses show that phosphorylated vimentin plays the dominant role in targeting IDE to the vimentin/nestin particles in vivo, while the requirement for nestin is related to its ability to promote vimentin IF disassembly. The binding of IDE to either nestin or phosphorylated vimentin regulates IDE activity differently, depending on the substrate. The insulin degradation activity of IDE is suppressed ∼50% by either nestin or phosphorylated vimentin, while the cleavage of bradykinin-mimetic peptide by IDE is increased 2- to 3-fold. Taken together, our data demonstrate that the nestin-mediated disassembly of vimentin IFs generates a structure capable of sequestering and modulating the activity of IDE.—Chou, Y.-H., Kuo, W.-L., Rich Rosner, M., Tang, W.-J., Goldman, R. D. Structural changes in intermediate filament networks alter the activity of insulin-degrading enzyme.

Keywords: phosphorylation, metalloprotease, cytoskeleton

Intermediate filaments (IFs) are one of the three major cytoskeletal components of mammalian cells. While the major cellular function of IFs is to provide mechanical strength to cells and tissues, there is increasing evidence that IFs also have many nonmechanical functions (1). For example, fibroblasts derived from vimentin-null mice are mechanically impaired and display deficiencies in wound repair (2). In a similar fashion, the process of transcellular migration of leukocytes across capillary walls is compromised when vimentin is absent in these cells (3). The impaired migration of vimentin-null cells can be, in part, attributed to the function of vimentin in attenuating the proteasomal degradation of a polarity factor, Scribble (4). Keratin IFs also participate in the regulation of a variety of cellular processes such as cell growth, apoptosis, and response to environmental stress (5,6,7,8).

Although the molecular details underlying IF-mediated functions are unclear, there is evidence that many of these functions are related to signal processing. IF proteins, such as vimentin, can form a number of interconvertible structures, including long filaments, short filaments (squiggles), and nonfilamentous aggregates (particles). All of these structures are motile due to their association with molecular motors such as dynein and kinesin (9, 10). The structural forms of IFs can serve as scaffolds that interact with signaling molecules and as a consequence modulate their activity and distribution within cells (8, 11). For example, a soluble form of vimentin has been shown to serve as a scaffold which connects activated MAP kinase to the retrograde motor dynein, thereby facilitating the transport of this kinase from the site of injury in axons to the nucleus (12). Similarly, it has been suggested that vimentin in a phosphorylated and possibly disassembled form is involved in the recycling of endocytosed β-integrins to the plasma membrane during cell migration (13).

The expression of vimentin and nestin is developmentally regulated. For example, nestin is transiently associated with progenitor cells of the developing nervous system and skeletal muscle (14, 15). In vitro, the levels of nestin expression are correlated with the replication potential of cultured progenitor cells (16, 17). Related to this role, nestin has also been identified as a potential modifier of malignancy in a number of human tumors (18,19,20,21,22). The mechanisms that are responsible for nestin’s involvement in enhancing cell proliferation are largely unknown.

Insulin-degrading enzyme is an evolutionarily conserved Zn2+-metalloprotease that plays a role in the degradation of insulin in endosomal compartments and in the clearance of amyloid-β peptides in the extracellular environment (23,24,25). It can also serve as a cellular receptor for viral infection (26). However, the ubiquitous expression of insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE) in almost all cell types and its mainly cytosolic distribution suggest that this enzyme may also be involved in the regulation of the turnover of yet-to-be identified substrates. Amyloidogenic peptides or proteins with a high propensity to aggregate are likely candidates. In support of this possibility, some of the established IDE substrates, such as insulin, amyloid β, and islet amyloid polypeptide, are all amyloidogenic peptides (23, 27). Both biochemical and structural studies reveal that IDE uses the size and charge distribution of its catalytic chamber to selectively degrade the monomeric, not the aggregated, form of these peptides (28, 29). Thus, IDE likely plays a role in preventing cytosolic peptides from forming the unwanted aggregates. To date, the IDE-targeted cytosolic peptides and the regulation of IDE-mediated degradation in the cytosol remain unclear.

Reversible phosphorylation is essential for regulating the dynamic properties and assembly/disassembly states of IFs (1, 30). In cells, nestin promotes the disassembly of vimentin IFs into nonfilamentous particles during mitosis in a phosphorylation-dependent manner (31). Nestin is the largest member of the IF protein family. Its highly conserved central rod domain, which is typical of all IF proteins, is flanked by an extremely long C terminus of >1200 aa and an extremely short N terminus of only 6 aa. Recently, it has been shown that a section of the tail domain interacts with and sequesters cdk5, thereby protecting cells from oxidative stress-induced apoptosis (32). This latter observation led us to search for additional vimentin/nestin binding partners, and the potential functions of the vimentin/nestin disassembly products known as particles in mitotic cells. In this report, we describe the identification of IDE as an additional cellular enzyme that is capable of interacting with the nestin/vimentin complex in a regulated fashion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Identification of IDE as a nestin-binding protein

Recombinant truncated rat nestin(641–1177) was coupled to Affi-gel-10 according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). M-phase extracts were prepared from activated Xenopus oocytes, as described previously (33). For affinity absorption, the egg extracts were mixed 1:1 with ice-cold buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.6), 100 mM NaCl, 50 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EGTA, and 10 μg/ml cytochalasin B, and centrifuged at 200,000 g for 30 min. The supernatant was saved and mixed with Affi-gel-10 beads coupled with either nestin(641–1177) or BSA for 1 h in the cold room. The beads were then rinsed 3 times with the buffer, and the proteins associated with the beads were eluted with the buffer brought to 1.5 M NaCl. The identity of the Xenopus 105-kDa band was determined by mass spectrometry analysis using the nano LC/MS/MS technique, which was carried out by Proteomic Research Services (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Briefly, the 105-kDa band was purified by SDS-PAGE, and the gel slice containing the 105-kDa band was excised, rinsed, and treated with trypsin. The hydrolysate was processed on a 75-μm C18 column at a flow rate of 200 nl/min. MS/MS data were searched using MASCOT (http://www.matrixscience.com). A total of 13 peptides were found to match the human IDE sequence (Supplemental Fig. 1).

IF purification and immunoprecipitation

For the separation of pelletable IF fractions from soluble fractions, cultured cells were lysed in an IF lysis buffer (PBS plus 0.6 M KCl, 5 mM EDTA, and 1% Triton X-100) and a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min (34). Immunoprecipitation was performed according to established protocols (34, 35). The relative amounts of vimentin and nestin in the soluble and pelletable fractions were determined using quantitative Western blot analysis, as described previously (36).

Expression of recombinant proteins

Expression and purification of recombinant vimentin was described in our previous study (37), and construction of the GFP-tagged nestin expression vectors [pEGFP-nestin(1–1893), pEGFP-nestin(1–314)] was reported in a recent article (32). The cDNA for rat IDE was amplified by RT-PCR using RNA from rat C6 glioma cells and was cloned into pGEX-4T-3 vector (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ, USA) between the BamH1 and XhoI sites. GST-tagged rat IDE was purified using a GSH-coupled column, and the IDE mutant (E111Q) was expressed and purified as described previously (38). The cDNAs encoding the His-tagged nestin fragments, nestin(1–314), nestin(315–640), nestin(641–1177), and nestin(1178–1893) were amplified by PCR using the pCMV-nestin vector (31) as a template and cloned into the pET-24a vector (Novagen, Madison, WI, USA) between the EcoRI and SalI sites. The His-tagged recombinant proteins were expressed and purified using a nickel column. Untagged nestin(1–640) and nestin(1–1177) were expressed using the pET24 vector and purified employing the same protocol as described for vimentin (37). Purified nestin fragments and GST-IDE were dialyzed extensively against PBS and kept frozen at −80°C.

Protein phosphorylation and solid-phase binding assays

The purification of cdk1 kinase and protein phosphorylation assays were carried out as described previously (39). The stoichiometry of 32P incorporated into each protein was measured using the Packard Cyclone storage phosphor system (Perkin Elmer, Wellesley, MA, USA). Interactions between IDE and recombinant vimentin or nestin fragments were characterized using polystyrene 96-well plates (Corning, Corning, NY, USA). Plates were coated with 10 pmol of each protein in 100 μl of TBS/well for 2 h at room temperature, and the unoccupied binding sites were blocked with 10 mg/ml of BSA in TBS for 1 h. The wells were then incubated with 30 pmol of GST-IDE, or GST as a negative control, in 100 μl of TBS and 1% BSA at room temperature for 1 h. The unbound GST-IDE or GST was removed by rinsing 4 times with TBS. The bound GST or GST-IDE was reacted with a monoclonal anti-GST antibody (Novagen) followed by an alkaline phosphatase conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Reactions were detected colorimetrically with p-nitrophenyl phosphate as substrate at 405 nm.

Immunofluorescence and antibodies

Confocal fluorescence microscopy was carried out as described previously (31). Polyclonal rabbit (PRB-282C) and monoclonal mouse antibodies (MMS-282R) directed against human IDE were obtained from Covance (Evansville, IN, USA). The monoclonal antibody directed against GFP (clones 7.1 and 13.1) was purchased from Roche. The monoclonal antibody (411C) directed against BHK nestin and rabbit anti-nestin and vimentin was used for both immunoprecipitation and immunofluorescence studies, as described earlier (31).

Enzymatic assays of GST-IDE

The proteolytic activity of GST-IDE was measured with either a fluorogenic peptide substrate V (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) or human insulin (Sigma). The bradykinin-mimetic fluorogenic peptide substrate V was used at 10 μM concentration in 100 μl of a solution containing 20 mM NaPO4 (pH 7.4) and 100 mM NaCl at 37°C for 30 min (40). The enzymatic activity was determined on a Tecan Safire II fluorescence plate reader (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland) using an excitation wavelength of 300 nm and an emission wavelength of 400 nm. When insulin was used as the substrate, the assays were carried out in a 40-μl reaction mixture containing 20 mM NaPO4 (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl, 350 ng of GST-IDE, and 1.6 μg of 125I-insulin (NEX420; Perkin Elmer). The reaction was incubated at 37°C for 30 min and terminated by adding SDS-PAGE sample buffer. The samples were then resolved by Tris/Tricine SDS-PAGE (41) and visualized by Coomassie blue staining. Undigested insulin bands were excised and counted with a γ counter.

RESULTS

A nestin tail fragment interacts with insulin-degrading enzyme in Xenopus egg extracts

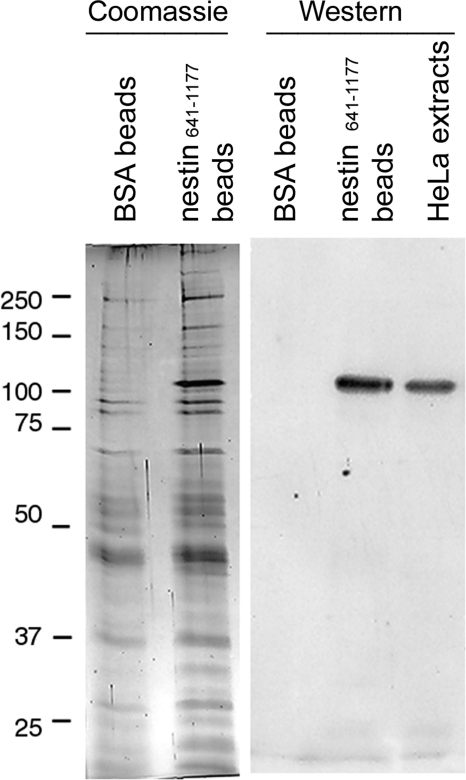

Nestin has an unusually long C-terminal non-α-helical tail domain, which, in the case of rat nestin, is >1579 aa long. We recently showed that the proximal section of this tail domain [nestin(315–640)] is involved in the sequestration and attenuation of p62/cdk5 activity (32). Adjacent to this p62/cdk5 binding domain is a relatively conserved sequence motif (residues 641–1177), consisting of a series of 11-aa repeats with no known function (42). Because such repeat sequence motifs are frequently involved in protein-protein interactions, we used the nestin(641–1177) fragment (see Fig. 3B) as bait to identify additional nestin-binding proteins by affinity chromatography. To this end, we used extracts prepared from Xenopus eggs as the source of potential nestin interacting proteins, as it has been well established that these readily prepared extracts contain stockpiles of components required for early embryonic development. The extracts were mixed with nestin(641–1177) conjugated to Affi-gel beads, and the proteins retained by the beads were eluted with 1.5 M NaCl (see Materials and Methods). As shown in Fig. 1, a number of proteins were retained by the nestin(641–1177)-coupled beads (Fig. 1). Most of these proteins appear to interact with the beads in a nonspecific manner, as they were also retained by BSA-coupled beads (Fig. 1). However, there was a prominent protein of ∼105 kDa that was specifically retained by this nestin fragment.

Figure 1.

Interaction between Xenopus egg IDE and nestin. Egg proteins eluted by 1.5 M salt from BSA-conjugated or nestin(641–1177)-conjugated beads were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Coomassie blue). Same samples were analyzed by Western blot analysis using a rabbit antibody specific for human IDE. Whole-cell extract prepared from HeLa cells was used as a positive control for the antibody.

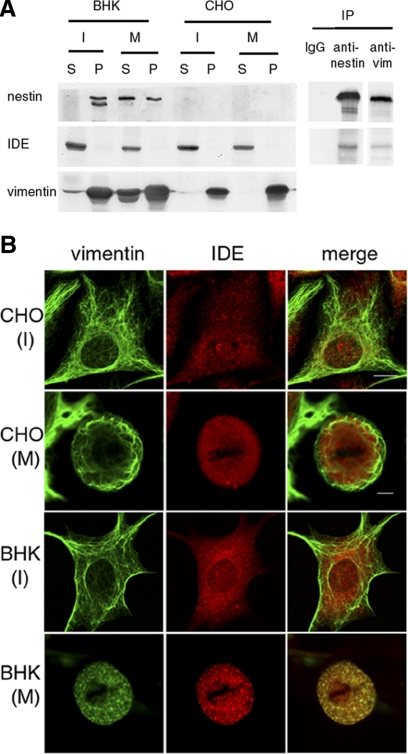

Figure 2.

IDE interacts with the disassembled and soluble complex of vimentin/nestin. A) Nonsynchronized (I) or mitotic (M) CHO and BHK-21 cells were lysed and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min to separate the pelletable (P) IF fraction from the soluble (S) fraction (see Materials and Methods). Samples of the soluble and pelletable fractions were equalized in volume and analyzed by Western blot analysis using antibodies specific for nestin, vimentin, and IDE. Immunoprecipitation (IP) of the soluble fraction from mitotic BHK-21 cells was carried out using rabbit anti-nestin and vimentin, and the immunoprecipitates were then probed with monoclonal anti-nestin (401C) and IDE (282R). B) Double-indirect immunofluorescence with antibodies directed against IDE and vimentin was performed in interphase (I) and mitotic (M) CHO and BHK-21 cells. Mitotic cells were identified by phase contrast. Colocalization IDE and vimentin are seen only in mitotic BHK-21 cells when vimentin is disassembled into nonfilamentous particles. Scale bars = 10 μm.

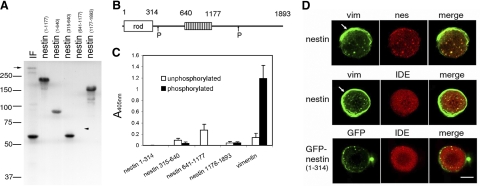

Figure 3.

Protein phosphorylation and vimentin/nestin-IDE interactions. A) Autoradiogram of 32P-labeled vimentin and nestin fragments after phosphorylation by the mitotic cdk1 kinase. Equal amounts (25 pmol) of each protein were loaded on the SDS-PAGE, and the extent of phosphorylation was measured using a beta imager. IF-enriched preparations were obtained from ST15A cells. These are enriched for vimentin and nestin and can be phosphorylated by cdk1. The rather weak 32P signal of nestin (∼300 kDa; arrow) is due to its minor concentration relative to vimentin. Phosphorylation levels (mol Pi/mol protein): nestin(1–1177), 0.88; nestin(1–640), 0.41; nestin(315–640), 0.72; nestin(1178–1893), 0.77. Nestin(641–1177) (arrowhead) is not phosphorylated by cdk1. B) Diagram summarizing the domains and relative positions of phosphorylation in rat nestin. Nestin consists of a very short 6-aa head domain and an α-helical domain of 308 aa, followed by a long non-α-helical C-terminal tail. The 11-aa repeat region is located between residues 641 and 1177. The cdk1 phosphorylation sites (P) are indicated with arrows; one of these phosphorylation sites is at Ser-316 (44). C) Solid-phase assay was employed to access the binding affinity between vimentin and GST-IDE, and between nestin and GST-IDE. Both unphosphorylated and cdk1-phosphorylated proteins were used. D) Nestin expression affects the assembly state of vimentin and induces the association of IDE with disassembled vimentin. HeLa cells were transfected with either the full-length nestin(1–1893) (nestin) or the nestin with only the rod domain [GFP-nestin(1–314)]. The mitotic cells were identified by phase contrast, and the assembly state of vimentin and the distribution of IDE were examined by indirect immunofluorescence. Formation of vimentin particles was only observed in cells expressing nestin constructs, and association of IDE with vimentin was only detected in these nestin-enriched vimentin particles. There are vimentin fibrils (white arrows, top and middle panels) located mainly in the peripheral region of these nestin expressing cells, and these show no association with IDE. Scale bar = 10 μm.

To determine the identity of this 105-kDa protein, the salt-eluted sample was separated by SDS-PAGE. The 105-kDa protein was identified by Coomassie blue staining, excised, and analyzed by mass spectrometry. Among all of the tryptic peptides derived from this 105-kDa protein, 13 of them matched the molecular mass of the peptides derived from a human protein called IDE (Supplemental Fig. 1). To further confirm the identity of this protein, the 105-kDa-enriched fraction was immunoblotted with rabbit anti-human IDE. As is shown in Fig. 1, the 105-kDa protein was recognized by this antibody. Furthermore, the Xenopus 105-kDa protein has the same apparent molecular mass as human IDE (Fig. 1). Taken together, the results of mass spectrometry and immunological analysis suggest that the 105-kDa protein is the Xenopus homologue of IDE.

Nestin interacts with IDE during mitosis

IDE is a ubiquitous and predominantly cytosolic protein in mammalian cells (23, 43). Because nestin is not present in eggs, it was important to determine whether the interaction between nestin and IDE found in Xenopus egg extracts could be detected in cultured mammalian cell types known to express nestin, such as BHK-21, and null for nestin, such as CHO (31). When nonsynchronized interphase CHO cells were lysed in IF lysis buffer, almost all of the vimentin was pelletable (Fig. 2A). The vimentin/nestin complex in BHK-21 cells displayed the same distribution (Fig. 2A). The nestin in interphase BHK-21 cells appeared as a doublet, and the slower-moving band may be a phosphorylation variant (see ref. 44 and below). When the IF samples were prepared from cell populations enriched for mitotic cells, the vimentin fraction in CHO cells remained in the pelletable fraction. In contrast, significant amounts of vimentin and nestin in BHK-21 cells were redistributed to the soluble fraction (34% for vimentin, 57% for nestin). The increased solubility of vimentin and nestin in mitotic cells is consistent with our earlier report that nestin promotes vimentin IF disassembly in mitotic cells (31). The pelletable vimentin and nestin in mitotic cell extracts may be attributable, at least in part, to the small fraction (∼15%) of mitotic cells that express lower levels of nestin (unpublished results) and do not disassemble their IFs (37). When the same samples were blotted with anti-IDE, this enzyme was found only in the soluble fraction of mitotic cells, suggesting that there was little or no interaction between filamentous vimentin/nestin with IDE. Because a significant fraction of vimentin and nestin in BHK-21 cells becomes soluble during mitosis, we determined whether soluble vimentin and nestin were associated with IDE in mitotic cells. For this purpose, soluble extracts from mitotic BHK-21 cells were immunoprecipitated with an affinity-purified anti-nestin and subsequently blotted with anti-IDE. As seen in Fig. 2A, the nestin-specific antibody brought down IDE, while preimmune IgG did not. Since vimentin and nestin form a complex, IDE could also be detected in the IP sample using vimentin-specific antibody (Fig. 2A).

Immunofluorescence was used to determine the distribution of vimentin/nestin and IDE in both interphase and mitotic cells. Since the distribution of nestin is coincident with that of vimentin during both interphase and mitotic stages (31), only images stained with vimentin antibodies are presented. As is shown in Fig. 2B, the distribution of IDE is partly diffuse and partly punctate throughout the cytoplasm in both interphase and mitotic CHO and BHK-21 cells. There is no apparent colocalization between IDE and filamentous IFs of either cell type during interphase (Fig. 2B). We previously reported that IF networks can undergo dramatic reorganization when cells enter mitosis, depending on the expression levels of nestin (31). In CHO cells that express no nestin, vimentin IFs form a filamentous cage around the mitotic spindle, while in BHK-21 cells that express a relatively high level of nestin, vimentin IFs disassemble into nonfilamentous particles. As is shown in Fig. 2B, vimentin IFs in mitotic CHO cells do not show an obvious association with IDE. In contrast, a significant fraction of IDE is coincident with the vimentin/nestin particles in mitotic BHK-21 cells (Fig. 2B). This colocalization of vimentin/nestin particles with IDE in mitotic cells has also been observed when cells normally null for nestin expression are transfected with nestin cDNA (see Fig. 3 below). Taken together, the morphological and biochemical results described above demonstrate that the interaction between IDE and vimentin/nestin complexes is a temporally regulated event that occurs preferentially when the vimentin/nestin complex is disassembled during mitosis.

Phosphorylation regulates the vimentin/nestin-IDE interaction

The finding that interactions between IDE and vimentin/nestin complexes are only detected during mitosis suggests that protein phosphorylation plays a role in this interaction. Since nestin is a substrate for cdk1 kinase during mitosis (44), we determined whether the binding affinity between IDE and nestin was affected by cdk1-mediated phosphorylation. First, we identified the domains of nestin phosphorylated by cdk1 using several smaller overlapping fragments of nestin, which is too large to be expressed in its full-length form. Each of these fragments was tested to determine whether it could be phosphorylated by cdk1. Because vimentin is also a substrate for cdk1 (39), it was included as a control for both the phosphorylation and binding assays. The results show that both full-length vimentin and nestin are substrates for cdk1 (Fig. 3A, lane IF). Among the 5 nestin fragments tested, 4 of them were phosphorylated, while nestin(641–1177) was not (Fig. 3A). Since the first 314 aa residues of nestin consist mainly of the α-helical central rod domain, which is not a substrate for any known protein kinases (1, 30, 45), this result demonstrates that the phosphorylation sites are confined to two fragments, nestin(315–640) and nestin(1177–1893) (Fig. 3B). One of the sites has previously been shown to be Ser-316 (44).

Once the domains of nestin phosphorylated by cdk1 were identified, a solid-phase binding assay was employed to measure the binding affinity between these nestin fragments and GST-IDE (see Materials and Methods). The results demonstrate that nestin(641–1177) had the highest level of GST-IDE binding of all nestin fragments (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, phosphorylation did not appear to affect the interactions between GST-IDE and other nestin fragments. To our surprise, while unphosphorylated and phosphorylated vimentin were intended as negative controls, phosphorylated vimentin turned out to bind more GST-IDE than nestin(641–1177) (Fig. 3C). There was no detectable interaction between GST and any of the vimentin and nestin fragments (data not shown).

The affinity between GST-IDE and phosphorylated vimentin prompted us to carry out additional experiments to evaluate the relative importance of phosphorylated vimentin and nestin in mediating the interaction between vimentin/nestin and IDE in mitotic cells. For this purpose, we used HeLa cells that express very low levels of nestin and consequently have vimentin networks that remain filamentous in mitosis (46), as is the case with CHO cells (Fig. 2B). We have shown previously that both full-length nestin [GFP-nestin(1–1893)] and tailless nestin [GFP-nestin(1–314)] are incorporated into endogenous vimentin IF networks (31, 32). When mitotic HeLa cells expressing either of these nestin constructs were examined, the vimentin IF network was disassembled into vimentin/nestin particles. However, the nestin-induced disassembly of vimentin IFs in mitotic HeLa cells was not complete, and residual IFs were frequently seen in peripheral regions (Fig. 3D, top and middle panels). The partial disassembly can be attributed to the preferential association of nestin with the vimentin particles (Fig. 3D, top panel). Nevertheless, in mitotic HeLa cells expressing either of these nestin constructs most of the nonfilamentous vimentin/nestin particles are enriched for IDE, while filamentous vimentin shows no obvious association with IDE (Fig. 3D, middle and bottom panels). It is known that vimentin IF disassembly during mitosis depends on both vimentin phosphorylation at Ser-55 and nestin (31). The results shown in Fig. 3D demonstrate that the nestin rod domain is sufficient to mediate the phosphorylation-dependent disassembly of vimentin IFs. Therefore, the non-α-helical C-terminus of nestin appears to play a minor role in the binding of IDE. The weaker interaction between nestin and IDE may be a reflection of the observation that IDE-nestin interaction is salt sensitive (Fig. 1). Taken together with the in vitro binding data (Fig. 3C), our results suggest that cdk1 phosphorylated vimentin plays a predominant role in binding to IDE, while nestin facilitates this function by promoting the disassembly of vimentin IFs, presumably by rendering the phosphorylated vimentin more accessible for interaction with IDE.

Both vimentin and nestin regulate IDE activity

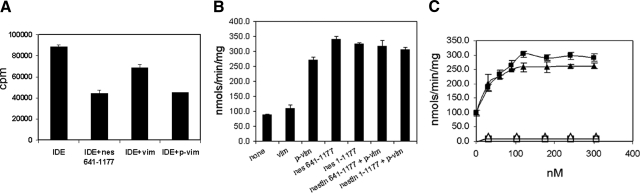

The finding that IDE binds to vimentin and nestin(641–1177) suggests that this interaction may modulate the activity of IDE. We measured the enzymatic activity of IDE using insulin, one of the established IDE substrates, as well as a bradykinin-mimetic fluorogenic peptide substrate V in common use for protease assays (40). As is shown in Fig. 4A, when the enzymatic activity of the recombinant GST-IDE was measured using 125I-insulin as substrate, the addition of either phosphorylated vimentin or nestin(641–1177) resulted in a ∼50% reduction of its basal activity. The addition of unphosphorylated vimentin in this assay also shows a slight suppression (∼20%) in IDE activity. However, when the bradykinin-mimetic fluorogenic peptide V was employed as a substrate, the addition of phosphorylated vimentin or nestin(641–1177) resulted in enzymatic activities, which were 2- to 3-fold greater than the basal level. The addition of a longer nestin fragment [nestin (1–1177)] showed no further enhancement of IDE activity (Fig. 4B). This latter result confirms the binding data described above (see Fig. 3C) and shows that the residues between 641 and 1177 of nestin constitute the major domain required for interaction with IDE. The inclusion of both phosphorylated vimentin and nestin fragments in the same reaction mixtures did not further enhance IDE activity (Fig. 4B), suggesting that phosphorylated vimentin and nestin interact with the same IDE domain. The activation of IDE by phosphorylated vimentin and nestin is saturable, and the apparent Ka for phosphorylated vimentin or nestin(1–1177) appears to be in the lower nanomolar range (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, control assays using GST or an IDE mutant with ablated enzymatic activity (IDE E111Q; ref. 38), did not give detectable activity or activation (Fig. 4C; GST data are not shown). The opposing results derived from the two different substrates, insulin, and bradykinin-mimetic peptide V, may be a reflection of how the specificity and activity of IDE are determined (see Discussion).

Figure 4.

Vimentin and nestin alter the IDE activity. A) Both vimentin and nestin(641–1177) suppress IDE insulin-degrading activity. Ability of the recombinant GST-IDE to degrade 125I-insulin was measured in the absence or presence of 200 nM vimentin, phosphorylated vimentin, or nestin(641–1177). B) Activity of GST-IDE toward bradykinin-mimetic fluorogenic peptide V was measured in the absence or presence of 200 nM vimentin and/or nestin fragments. C) Activity of GST-IDE was studied in the presence of increasing concentration of either phosphorylated vimentin (solid triangles) or nestin(1–1177) (solid squares). To rule out the possibility that the recombinant GST-IDE may be tainted with other protease activities, an enzymatically inactive recombinant IDE mutant (IDE E111Q) was also assayed as a function of increasing amounts of phosphorylated vimentin (open triangles) or nestin(1–1177) (open squares).

DISCUSSION

Previously, we demonstrated that the disassembly of vimentin IFs into nonfilamentous particles during mitosis is mediated by phosphorylation of vimentin at Ser-55 and nestin (31). In this study, we present evidence that this unique form of vimentin/nestin complex is capable of sequestering IDE in a phosphorylation-dependent manner. This regulated association of vimentin/nestin particles with IDE during mitosis and its concomitant modulation of IDE activity establish an interesting example of how structural changes in IFs can be linked to the sequestration and altered activity of IDE.

There are numerous examples showing that the phosphorylation of IF proteins is associated with many physiological activities. For example, a phosphorylation-dependent interaction between the 14-3-3 family of proteins and vimentin has been reported, although the functional significance of this interaction remains unclear (47). In another example, phosphorylation of keratin 18 at Ser-33 has been shown to be required for its interaction with 14-3-3, which regulates the mitotic progression of hepatocytes and the translocation of 14-3-3 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm during liver regeneration (48, 49). In a similar fashion, phosphorylation of keratin 17 has been linked to growth regulation by modulating the translocation of 14-3-3ς from the nucleus to the cytoplasm and its subsequent activation of the mTOR pathway and protein synthesis during skin wound repair (7).

The results of vimentin/nestin-modulated IDE activities are intriguing. It appears that vimentin/nestin complexes can either activate or suppress the proteolytic activity of IDE, depending on the substrates used. The recently deciphered crystal structure of IDE in the presence of different substrates provides clues that may help to explain these results. The latter studies show that IDE is composed of two bowl-shaped halves connected by a flexible latch. Enclosed within these bowl-shaped domains is a catalytic chamber that switches between a closed state and an open state during enzymatic cycles (29). Although IDE can degrade both larger substrates, such as insulin (51 aa), as well as smaller peptides, such as bradykinin-mimetic peptide substrate V (9 aa), the kinetics of the cleavage of these two substrates are very different. Results from several studies reveal that IDE has a low-affinity binding for bradykinin-mimetic peptide substrate V (Km∼4.2 mM), but can cleave it at higher rates (∼2000 s−1); whereas IDE has a much higher affinity for insulin (Km∼100 nM) but cleaves it at a much slower rate (∼0.5 min−1) (50,51,52). These kinetic differences are attributable to the possibility that IDE only needs to partially open its catalytic chamber to capture bradykinin-mimetic peptide substrate V, while a fully opened catalytic chamber is required to accommodate insulin. Although the domain of IDE involved in its interaction with vimentin/nestin is unknown, it is likely that the binding of vimentin/nestin to IDE may modulate the extent and/or the switch rate between the open and closed states of the IDE catalytic chamber. This modulation may on the one hand facilitate the degradation of short peptide substrates, such as bradykinin-mimetic substrate V and on the other hand slow down the cleavage of larger substrates such as insulin.

The potential substrates for IDE associated with the cytoskeletal vimentin/nestin particles remain to be identified. IF proteins do not appear to be the substrates for IDE (Supplemental Fig. 2). The known IDE substrates, such as insulin and amyloid β, are processed in endosomal and extracellular compartments (see ref. 23 for a review) and therefore are unlikely to be targets for IDE in the cytosol. As IDE is a ubiquitous component of the cytosol of the majority of vertebrate tissues, the ability of nestin and vimentin to interact and modulate IDE activity suggests that it is involved in the regulation of the turnover of unknown cytosolic proteins and peptides. Interestingly, IDE has been shown to associate with the 26S proteasome and regulate its activity in vitro (53). Furthermore, vimentin is frequently observed to form a cage around a specialized pericentriolar organelle termed the aggresome, which consists of aggregated and ubiquitinated cellular proteins (54). The interaction between vimentin/nestin and IDE could, therefore, play a role in connecting the turnover of specific cytosolic proteins to the proteasomal machinery. Related to this suggestion, vimentin expression has been shown to attenuate the proteasome-mediated degradation of Scribble, a cell-polarity-determining protein during cell migration (4).

Nestin expression is frequently used as a hallmark of the early differentiation of embryonic stem cells, although the functional significance of its transient expression remains unknown. However, over the past several years, it has been shown that nestin-expressing stem or progenitor cells frequently undergo asymmetric cell division, resulting in the preferential distribution of nestin and other cellular factors into one of the two daughter cells (16, 55, 56). It is interesting to speculate that this asymmetric distribution of protein factors could be achieved by the targeted degradation of specific factors associated with the vimentin/nestin particles delivered to one daughter cell following cytokinesis. Future elucidation of the targets of the cytosolic IDE will certainly advance our understanding into the functional significance of its interaction with vimentin/nestin complexes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Edward Kuczmarski and Dr. Stephen Adam for critically reading the manuscript and for suggestions. This research is supported by a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences to R.D.G.

References

- Omary M B, Ku N O, Tao G Z, Toivola D M, Liao J. “Heads and tails” of intermediate filament phosphorylation: multiple sites and functional insights. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckes B, Colucci-Guyon E, Smola H, Nodder S, Babinet C, Krieg T, Martin P. Impaired wound healing in embryonic and adult mice lacking vimentin. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:2455–2462. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.13.2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieminen M, Henttinen T, Merinen M, Marttila-Ichihara F, Eriksson J E, Jalkanen S. Vimentin function in lymphocyte adhesion and transcellular migration. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:156–162. doi: 10.1038/ncb1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phua D C, Humbert P O, Hunziker W. Vimentin regulates Scribble activity by protecting it from proteasomal degradation. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;12:2841–2855. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-02-0199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulin C, Ware C F, Magin T M, Oshima R G. Keratin-dependent, epithelial resistance to tumor necrosis factor-induced apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:17–22. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inada H, Izawa I, Nishizawa M, Fujita E, Kiyono T, Takahashi T, Momoi T, Inagaki M. Keratin attenuates tumor necrosis factor-induced cytotoxicity through association with TRADD. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:415–426. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200103078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Wong P, Coulombe P A. A keratin cytoskeletal protein regulates protein synthesis and epithelial cell growth. Nature. 2006;441:362–365. doi: 10.1038/nature04659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omary M B, Ku N O. Cell biology: skin care by keratins. Nature. 2006;441:296–297. doi: 10.1038/441296a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Goldman R D. Intermediate filaments mediate cytoskeletal crosstalk. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:601–613. doi: 10.1038/nrm1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou Y H, Flitney F W, Chang L, Mendez M, Grin B, Goldman R D. The motility and dynamic properties of intermediate filaments and their constituent proteins. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:2236–2243. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfand B T, Chou Y H, Shumaker D K, Goldman R D. Intermediate filament proteins participate in signal transduction. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:568–570. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlson E, Hanz S, Ben-Yaakov K, Segal-Ruder Y, Seger R, Fainzilber M. Vimentin-dependent spatial translocation of an activated MAP kinase in injured nerve. Neuron. 2005;45:715–726. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivaska J, Vuoriluoto K, Huovinen T, Izawa I, Inagaki M, Parker P J. PKCå-mediated phosphorylation of vimentin controls integrin recycling and motility. EMBO J. 2005;24:3834–3845. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lendahl U, Zimmerman L B, McKay R D. CNS stem cells express a new class of intermediate filament protein. Cell. 1990;60:585–595. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90662-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sejersen T, Lendahl U. Transient expression of the intermediate filament nestin during skeletal muscle development. J Cell Sci. 1993;106:1291–1300. doi: 10.1242/jcs.106.4.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi A, Miyata T, Sawamoto K, Takashita N, Murayama A, Akamatsu W, Ogawa M, Okabe M, Tano Y, Goldman S A, Okano H. Nestin-EGFP transgenic mice: visualization of the self-renewal and multipotency of CNS stem cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2001;17:259–273. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2000.0925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mignone J L, Kukekov V, Chiang A S, Steindler D, Enikolopov G. Neural stem and progenitor cells in nestin-GFP transgenic mice. J Comp Neurol. 2004;469:311–324. doi: 10.1002/cne.10964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlstrand J, Collins V P, Lendahl U. Expression of the class VI intermediate filament nestin in human central nervous system tumors. Cancer Res. 1992;52:5334–5341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutka J T, Ivanchuk S, Mondal S, Taylor M, Sakai K, Dirks P, Jun P, Jung S, Becker L E, Ackerley C. Co-expression of nestin and vimentin intermediate filaments in invasive human astrocytoma cells. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1999;17:503–515. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(99)00049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultana S, Zhou R, Sadagopan M S, Skalli O. Effects of growth factors and basement membrane proteins on the phenotype of U-373 MG glioblastoma cells as determined by the expression of intermediate filament proteins. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:1157–1168. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65660-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S K, Messam C A, Spengler B A, Biedler J L, Ross R A. Nestin is a potential mediator of malignancy in human neuroblastoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:27994–27999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312663200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohyama T, Lee V M, Rorke L B, Marvin M, McKay R D, Trojanowski J Q. Nestin expression in embryonic human neuroepithelium and in human neuroepithelial tumor cells. Lab Invest J Tech Methods Pathol. 1992;66:303–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth W C, Bennett R G, Hamel F G. Insulin degradation: progress and potential. Endocrine Rev. 1998;19:608–624. doi: 10.1210/edrv.19.5.0349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farris W, Mansourian S, Chang Y, Lindsley L, Eckman E A, Frosch M P, Eckman C B, Tanzi R E, Selkoe D J, Guenette S. Insulin-degrading enzyme regulates the levels of insulin, amyloid beta-protein, and the beta-amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4162–4167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0230450100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller B C, Eckman E A, Sambamurti K, Dobbs N, Chow K M, Eckman C B, Hersh L B, Thiele D L. Amyloid-beta peptide levels in brain are inversely correlated with insulysin activity levels in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6221–6226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1031520100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Ali M A, Cohen J I. Insulin degrading enzyme is a cellular receptor mediating varicella-zoster virus infection and cell-to-cell spread. Cell. 2006;127:305–316. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurochkin I V. Insulin-degrading enzyme: embarking on amyloid destruction. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26:421–425. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01876-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malito E, Hulse R E, Tang W J. Amyloid beta-degrading cryptidases: insulin degrading enzyme, presequence peptidase, and neprilysin. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:2574–2585. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8112-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Joachimiak A, Rosner M R, Tang W J. Structures of human insulin-degrading enzyme reveal a new substrate recognition mechanism. Nature. 2006;443:870–874. doi: 10.1038/nature05143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki M, Inagaki N, Takahashi T, Takai Y. Phosphorylation-dependent control of structures of intermediate filaments: a novel approach using site- and phosphorylation state-specific antibodies. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1997;121:407–414. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou Y H, Khuon S, Herrmann H, Goldman R D. Nestin promotes the phosphorylation-dependent disassembly of vimentin intermediate filaments during mitosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:1468–1478. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-08-0545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahlgren C M, Pallari H M, He T, Chou Y H, Goldman R D, Eriksson J E. A nestin scaffold links Cdk5/p35 signaling to oxidant-induced cell death. EMBO J. 2006;25:4808–4819. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newport J, Spann T. Disassembly of the nucleus in mitotic extracts: membrane vesicularization, lamin disassembly, and chromosome condensation are independent processes. Cell. 1987;48:219–230. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90425-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prahlad V, Yoon M, Moir R D, Vale R D, Goldman R D. Rapid movements of vimentin on microtubule tracks: kinesin-dependent assembly of intermediate filament networks. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:159–170. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.1.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou Y H, Rosevear E, Goldman R D. Phosphorylation and disassembly of intermediate filaments in mitotic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:1885–1889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.6.1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman R D, Khuon S, Chou Y H, Opal P, Steinert P M. The function of intermediate filaments in cell shape and cytoskeletal integrity. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:971–983. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.4.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou Y H, Opal P, Quinlan R A, Goldman R D. The relative roles of specific N- and C-terminal phosphorylation sites in the disassembly of intermediate filament in mitotic BHK-21 cells. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:817–826. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.4.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesneau V, Rosner M R. Functional human insulin-degrading enzyme can be expressed in bacteria. Protein Expr Purif. 2000;19:91–98. doi: 10.1006/prep.2000.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou Y H, Bischoff J R, Beach D, Goldman R D. Intermediate filament reorganization during mitosis is mediated by p34cdc2 phosphorylation of vimentin. Cell. 1990;62:1063–1071. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90384-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson G D, Ahn K. Development of an internally quenched fluorescent substrate selective for endothelin-converting enzyme-1. Anal Biochem. 2000;286:112–118. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schagger H, von Jagow G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem. 1987;166:368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlstrand J, Zimmerman L B, McKay R D, Lendahl U. Characterization of the human nestin gene reveals a close evolutionary relationship to neurofilaments. J Cell Sci. 1992;103:589–597. doi: 10.1242/jcs.103.2.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weirich G, Mengele K, Yfanti C, Gkazepis A, Hellmann D, Welk A, Giersig C, Kuo W L, Rosner M R, Tang W J, Schmitt M. Immunohistochemical evidence of ubiquitous distribution of the metalloendoprotease insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE; insulysin) in human non-malignant tissues and tumor cell lines. Biol Chem. 2008;389:1441–1445. doi: 10.1515/BC.2008.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahlgren C M, Mikhailov A, Hellman J, Chou Y H, Lendahl U, Goldman R D, Eriksson J E. Mitotic reorganization of the intermediate filament protein nestin involves phosphorylation by cdc2 kinase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16456–16463. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009669200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson J E, He T, Trejo-Skalli A V, Harmala-Brasken A S, Hellman J, Chou Y H, Goldman R D. Specific in vivo phosphorylation sites determine the assembly dynamics of vimentin intermediate filaments. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:919–932. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J C, Goldman A E, Yang H Y, Goldman R D. The organizational fate of intermediate filament networks in two epithelial cell types during mitosis. J Cell Biol. 1985;100:93–102. doi: 10.1083/jcb.100.1.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzivion G, Luo Z J, Avruch J. Calyculin A-induced vimentin phosphorylation sequesters 14-3-3 and displaces other 14-3-3 partners in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29,772–29,778. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001207200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku N O, Michie S, Resurreccion E Z, Broome R L, Omary M B. Keratin binding to 14-3-3 proteins modulates keratin filaments and hepatocyte mitotic progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:4373–4378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072624299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao J, Omary M B. 14-3-3 proteins associate with phosphorylated simple epithelial keratins during cell cycle progression and act as a solubility cofactor. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:345–357. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.2.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malito E, Ralat L A, Manolopoulou M, Tsay J L, Wadlington N L, Tang W J. Molecular bases for the recognition of short peptide substrates and cysteine-directed modifications of human insulin-degrading enzyme. Biochemistry. 2008;47:12822–12834. doi: 10.1021/bi801192h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safavi A, Miller B C, Cottam L, Hersh L B. Identification of γ-endorphin-generating enzyme as insulin-degrading enzyme. Biochemistry. 1996;35:14318–14325. doi: 10.1021/bi960582q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song E S, Daily A, Fried M G, Juliano M A, Juliano L, Hersh L B. Mutation of active site residues of insulin-degrading enzyme alters allosteric interactions. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17701–17706. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501896200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett J, Permana P A, Levy J L, Duckworth W C. Regulation of protein degradation by insulin-degrading enzyme: analysis by small interfering RNA-mediated gene silencing. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;468:128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston J A, Ward C L, Kopito R R. Aggresomes: a cellular response to misfolded proteins. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1883–1898. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.7.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieberich E, MacKinnon S, Silva J, Noggle S, Condie B G. Regulation of cell death in mitotic neural progenitor cells by asymmetric distribution of prostate apoptosis response 4 (PAR-4) and simultaneous elevation of endogenous ceramide. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:469–479. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakamatsu Y, Nakamura N, Lee J A, Cole G J, Osumi N. Transitin, a nestin-like intermediate filament protein, mediates cortical localization and the lateral transport of Numb in mitotic avian neuroepithelial cells. Development. 2007;134:2425–2433. doi: 10.1242/dev.02862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.