Abstract

Converging data suggest recovery from injury in the preterm brain. We used functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) to test the hypothesis that cerebral connectivity involving Wernicke’s area and other important cortical language regions would differ between preterm (PT) and term (T) control school age children during performance of an auditory language task. Fifty-four PT children (600 – 1250 g birth weight) and 24 T controls were evaluated using an fMRI passive language task and neurodevelopmental assessments including: the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children - III (WISC - III), the Peabody Individual Achievement Test - Revised (PIAT-R) and the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test - Revised (PPVT- R) at 8 years of age. Neural activity was assessed for language processing and the data were evaluated for connectivity and correlations to cognitive outcomes. We found PT subjects scored significantly lower on all components of the WISC - III (p < 0.009), the PIAT- R reading comprehension test (p = 0.013), and the PPVT-R (p = 0.001) compared to term subjects. Connectivity analyses revealed significantly stronger neural circuits in PT children between Wernicke’s area and the right inferior frontal gyrus (R IFG, Broca’s area homologue) and both the left and the right supramarginal gyri (SMG) components of the inferior parietal lobules (p ≤ 0.02 for all). We conclude that PT subjects employ neural systems for auditory language function at school age differently than T controls; these alterations may represent a delay in maturation of neural networks or the engagement of alternate circuits for language processing.

Keywords: connectivity, functional magnetic resonance imaging, premature, birth weight, outcomes

INTRODUCTION

Preterm infants are at high risk of brain injury. Almost 25% experience intraventricular hemorrhage, and as many as 80% have diffuse excessive high signal intensity within the white matter in the newborn period. (Dyet et al., 2006; Woodward et al., 2006) Macrostructural brain abnormalities have been correlated with adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes (Gimenez et al., 2006b; Peterson et al., 2000) and their presence may potentially disrupt the genetically programmed pattern of brain development. Numerous MRI studies have demonstrated that preterm children and adolescents have decreased cortical gray matter, cortical white matter, deep gray matter, cerebellar and total brain volumes when compared to age-matched term control subjects. (Gimenez et al., 2006a; Kesler et al., 2004; Kesler et al., 2008; Nosarti et al., 2002; Reiss et al., 2004) Similarly, diffusion tensor imaging studies have documented microstructural alterations in both the corpus callosum and those intra-hemispheric association fibers subserving language skills. (Constable et al., 2008)

In contrast to these data documenting aberrant brain development, behavioral data suggest a pattern of recovery and preserved performance. (Hack et al., 2005; Hack et al., 2002; Ment et al., 2003; Saigal et al., 2006) The advent of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has permitted the correlation of neurobiology and behavior in subjects of all ages, and numerous MRI studies have explored the structural, volumetric and microstructural sequelae of preterm birth. (Constable et al., 2008; Gimenez et al., 2006a; Kesler et al., 2006; Nosarti et al., 2002; Reiss et al., 2004) Functional MRI (fMRI), which assesses both neural processing and resting state cerebral activity, has been less well studied than other imaging strategies in the preterm population, but has the potential to offer important insights into the neurobiological mechanisms that support brain development. Most recently, functional neuroimaging data have been used to examine interactions between spatially distinct regions, or “functional connectivity,” in typically developing children and adolescents. (Fair et al., 2008; Fair et al., 2007) Functional connectivity studies assess “temporal correlations between spatially remote neurophysiological events”, (Friston et al., 1996) and all regions that respond to a specific task are correlated to varying degrees. Resting state research suggests that functional connectivity is at least partially anatomically determined. (Skudlarski et al., 2008) FMRI studies in the prematurely born suggest the engagement of alternative neural networks for language and memory (Gimenez et al., 2005; Ment et al., 2006a; Ment et al., 2006b) and further investigations of neural connectivity are needed to better understand this suggestion of plasticity in the preterm brain.

The connectivity between language regions during an fMRI auditory language task was investigated in preterm and term subjects. Wernicke’s area, in the left superior temporal gyrus (STG), is a well established language perception area in children that activated in both the preterm and term groups. This area was chosen as a reference region for functional connectivity analysis with other primary language regions in the left hemisphere and their right-sided homologues. Our a priori hypothesis was that cerebral connectivity between Wernicke’s and other language regions would differ significantly between preterm (PT) school age children and term (T) control subjects.

Since intraventricular hemorrhage, periventricular leukomalacia and low-pressure ventriculomegaly have been associated with adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes in the prematurely born, (Krishnamoorthy et al., 1979; McMenamin et al., 1984; Shinnar et al., 1982; Szymonowicz et al., 1986) our a priori hypothesis was tested in preterm subjects who were free of parenchymal lesions in both neonatal cranial ultrasound studies and magnetic resonance images at age 8.

METHODS

This study was performed at Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, and Warren Alpert Brown Medical School, Providence, RI. The protocols were reviewed and approved by institutional review boards at each location. Parent(s) provided written consent, and written assent was obtained from all study children. All scans were obtained and analyzed at Yale University School of Medicine.

Subjects and Their Assessment

Demographic, cognitive and fMRI BOLD data have been previously reported for this cohort to examine the impact of early low-dose indomethacin therapy on the developing brain. (Ment et al., 2006a; Ment et al., 2006b; Peterson et al., 2002) The preterm children were enrolled in the follow-up MRI component of the Multicenter Randomized Indomethacin IVH Prevention Trial at Yale University School of Medicine and Brown University. Only those children with no evidence for intraventricular hemorrhage or low-pressure ventriculomegaly who lived within 200 miles of the Yale MRI Research Facility were eligible for this protocol. From a potential pool of 194 subjects, 92 were randomly assigned to undergo fMRI examinations. Scans from the first 19 preterm subjects were performed with MRI software incompatible with that for the current study and could not be included in this study. Of the 73 remaining preterm subjects, 18 were excluded because of excess motion artifact, and one was removed secondary to periventricular leukomalacia. All 54 subjects with usable fMRI data at 7–9 years and 24 term age-matched control children recruited from the local communities of the study children are included in this report. (Ment et al., 2006a)

Neurodevelopmental Assessments

Assessments were performed at 8 years of age by testers blinded to the randomization status of the subjects in the IVH prevention study. The following tests were administered: 1.) the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children - Third Edition (WISC - III); 2.) the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Revised (PPVT-R); and 3.) the Reading Recognition, Reading Comprehension and Mathematics subtests of the Peabody Individualized Achievement Test - Revised (PIAT-R).

FMRI Study

An audiotaped passive auditory listening task in which the children listened to 3 varying stimulus presentations of a pleasant children’s story through headphones as previously described was administered. (Peterson et al., 2002) Head positioning in the magnet was standardized using the canthomeatal line. A T1-weighted sagittal localizing scan was used to position the axial images. In all subjects, 10 oblique axial slices were acquired to correspond with 10 axial sections of the Talairach coordinate system oriented parallel to the anterior commissure-posterior commissure (AC-PC) line. The slices were positioned with 2 slices below, 7 slices above, and 1 slice containing the AC-PC line. Slice thickness was a constant 7 mm, and the skip between slices varied between 0.5 and 2 mm to maintain a strict correspondence with the Talairach coordinate system across the axial slices.

Imaging was performed on a GE Signa LX system. The functional images were obtained with a blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) contrast gradient echo, echo planar imaging pulse sequence having a repetition time = 2060 msec, echo time = 45 msec, flip angle = 60°, 1 excitation per image, 20- x 40-cm field of view, and 64 × 128 matrix, providing a 3.1 × 3.1 mm in-plane resolution. During each run, 102 echoplanar images were acquired in each slice, providing 306 images per experiment and 102 images for each stimulus type.

Brain volumes were first slice time corrected and then motion corrected using the SPM 99 algorithm (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/) for 6 translation and rotation directions. Subjects with motion trajectories greater than 0.5 pixels were eliminated. Each subject’s 3D high resolution volume scan was registered to a common reference brain space, and all connectivity data were transformed to this common space for between-subject and between-group analyses using BioimageSuite (Bioimagesuite.org) software which also allowed for more accurate reporting of Talairach coordinates. (Lacadie et al., 2008)

ROI Connectivity Analyses

The synchrony of responses between regions as measured during the passive listening task was examined. Functional connectivity within each subject was measured as a correlation between a reference region of interest (ROI) and all other pixels within eleven other regions of interest that included the primary language regions and their homologues in the right hemisphere. The data used for the correlation analysis were the mean time-course BOLD fMRI data for each ROI obtained during the passive listening task. Wernicke’s area was chosen as the reference region for this study, defined anatomically as the posterior portion of left BA 22 with center of mass Talairach coordinates of −54, −36,10.

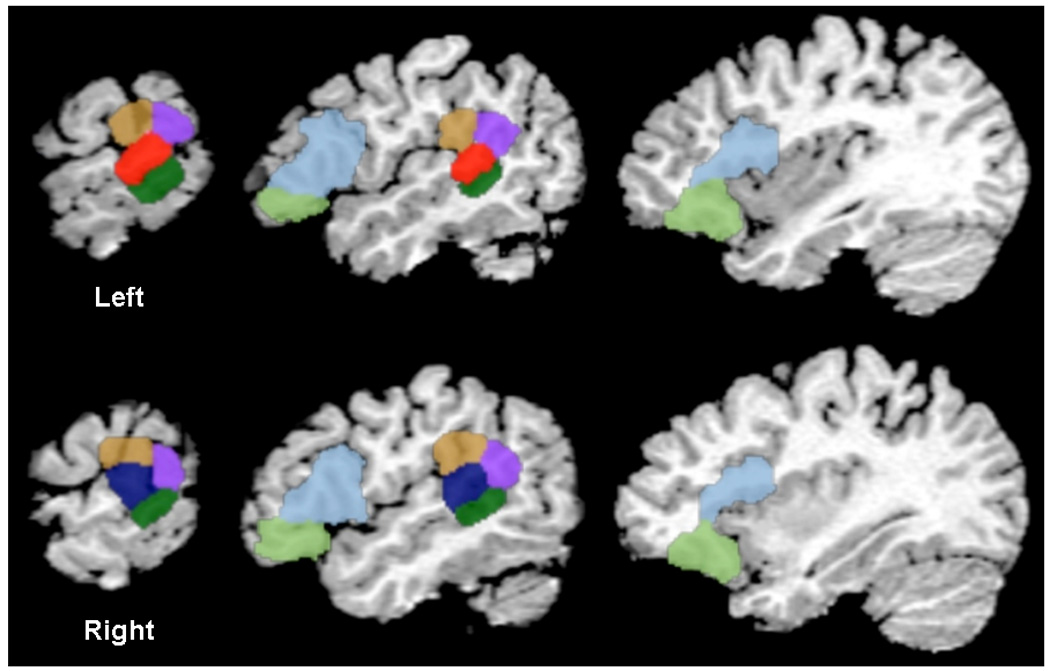

Language regions interrogated for connectivity to the seed region included eleven ROIs: bilateral Broca’s region (BA 44 and BA 45 combined), bilateral BA 47, posterior portions of bilateral BA 21, inferior portions of bilateral BA 40 and BA 39, and the homologue of the reference region, right posterior BA 22. BA 39 is the region of the angular gyrus and BA 40 is the supramarginal gyrus, a component of the inferior parietal lobule. All regions were defined anatomically in reference space as shown in Figure 1 with the center of mass Talairach coordinates listed in Table 1, as defined in the Yale Bioimagesuite Software (BioimageSuite.org). Correlation values to the reference ROI were normalized to a Gaussian distribution, and the mean value was extracted for each ROI for use in further statistical analyses.

Figure 1.

Anatomic ROIs interrogated for connectivity with Wernicke’s area, L BA 22 (red). ROIs examined for connectivity to Wernicke’s in preterms and terms include bilateral BA 21 (dark green), BA 39 (lilac), BA 40 (brown), BA 47 (light green), BA 44–45 (light blue) and R BA 22 (navy).

Table 1.

Talairach coordinates for connectivity from Wernicke’s area (−54, −36,10)

| Brodmann’s Areas (BA) | Talairach Coordinates |

|---|---|

| Left BA 21 | −56,−43,2 |

| Right BA 21 | 57,−40,5 |

| Right BA 22 | 56,−33,14 |

| Left BA 39 | −53,−46,26 |

| Right BA 39 | 56,−46,26 |

| Left BA 40 | −53,−33,23 |

| Right BA 40 | 56,−30,26 |

| Left BA 44–45 | −42,17,12 |

| Right BA 44 – 45 | 46,15,14 |

| Left BA 47 | −34,27,−12 |

| Right BA 47 | 38,27,−12 |

Statistical Analyses

Demographic and cognitive data were analyzed using standard chi-squared statistics for categorical data, and nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous-valued data. Mean correlation coefficients were determined by converting correlation values via Fisher’s z transformation, averaging them, and backtransforming to r-values according to the method of Silver and Dunlap. (Silver and Dunlap, 1987) The normalized correlation values were entered into a general linear model (GLM) to test the effect of diagnosis (PT or T) including covariates of VCIQ, age at scan, and gender and resulting p-values were corrected for multiple comparisons using a Bonferroni correction. A supplemental GLM explored the role of handedness and included covariates of VCIQ, age at scan, gender and right-handedness and determined p-values were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method. Using our a priori hypothesis, the relationship between connectivity data and neonatal variables was assessed in the preterm group using a third GLM. Neonatal variables included gender, birth weight, randomization to indomethacin, and years of maternal education. Analysis by gender was also used to correlate cognitive measures and connectivity data adjusting for age at scan. These statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.1.3, and all p-values are two-sided.

RESULTS

Subjects

Fifty-four preterm children and 24 term controls participated in this study. There were no significant differences between the two groups in the number of males, minority status, handedness, or years of maternal education. PT children were roughly a half-year older at the time of scan, (9.2 years versus 8.7 years, p = 0.002). As reported in Table 2, PT children scored lower than term controls in tests of cognitive function: FSIQ, VIQ, PIQ, VCIQ and PPVT (p = 0.002, 0.002, 0.005, 0.009 and 0.001 respectively) and Reading Comprehension (p = 0.013). A greater proportion of the PT children were receiving special services (56% versus 17%, p = 0.003) than term controls. Perinatal data for the PT subjects are shown in Table 3; of note, there were no significant gender differences for any of these variables.

Table 2.

Demographic and cognitive data for the study children

| Preterm | Term | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 54 | 24 | |

| Males | 28 (52%) | 11 (46%) | 0.81 |

| Right-handed | 44/51 (86%) | 22/23 (96%) | 0.42 |

| Minority status | 37 (69%) | 15 (63%) | 0.61 |

| Full Scale Intelligence Quotient | 95.5 ± 16.1 | 109.8 ± 13.6 | 0.002 |

| Verbal IQ | 99.2 ± 16.6 | 111.5± 11.4 | 0.002 |

| Performance IQ | 92.7 ± 16.4 | 106.0 ± 15.3 | 0.005 |

| Verbal Comprehension IQ | 100.5 ± 17.5 | 111.8 ± 12.1 | 0.009 |

| Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test | 95.2 ± 21.7 | 113.4 ± 17.8 | 0.001 |

| Reading Recognition* | 96.0 ± 19.8 | 107.3 ± 15.7 | 0.011 |

| Reading Comprehension* | 96.4 ± 21 | 109.3 ± 16.6 | 0.013 |

| Math* | 89.7 ± 18.7 | 108.4 ± 18.6 | 0.001 |

| Special services | 30 (56%) | 4/23 (17%) | 0.003 |

| Age at scan (years) | 9.2 ± 0.7 | 8.70 ± 0.6 | 0.002 |

| Maternal education < high school | 4/53 (7.6%) | 1(4.2%) | 1.00 |

PIAT-R

Table 3.

Perinatal data for the preterm subjects

| Number | 54 |

|---|---|

| Males | 28 (52%) |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 28.2 ± 1.9 |

| Birth weight (grams) | 977 ± 169.5 |

| Randomized to indomethacin | 29 (54%) |

| Antenatal steroids | 22/54 (41%) |

| Respiratory distress syndrome | 45 (83%) |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | 2 (4%) |

Correlation Coefficients

Mean group correlation coefficients for the connectivity data for each ROI from Wernicke’s region are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Correlation coefficients for connectivity from L Wernicke’s Region

| BA* Regions | Preterm | Term |

|---|---|---|

| Left BA 21 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.02 |

| Right BA 21 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.01 |

| Right BA 22 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.01 |

| Left BA 39 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.01 |

| Right BA 39 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.02 |

| Left BA 40 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.02 |

| Right BA 40 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.01 |

| Left BA 44–45 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.01 |

| Right BA 44–45 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.01 |

| Left BA 47 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.0003 ± 0.01 |

| Right BA 47 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | −0.004 ± 0.01 |

BA Brodmann’s Area

Values are mean ± standard error

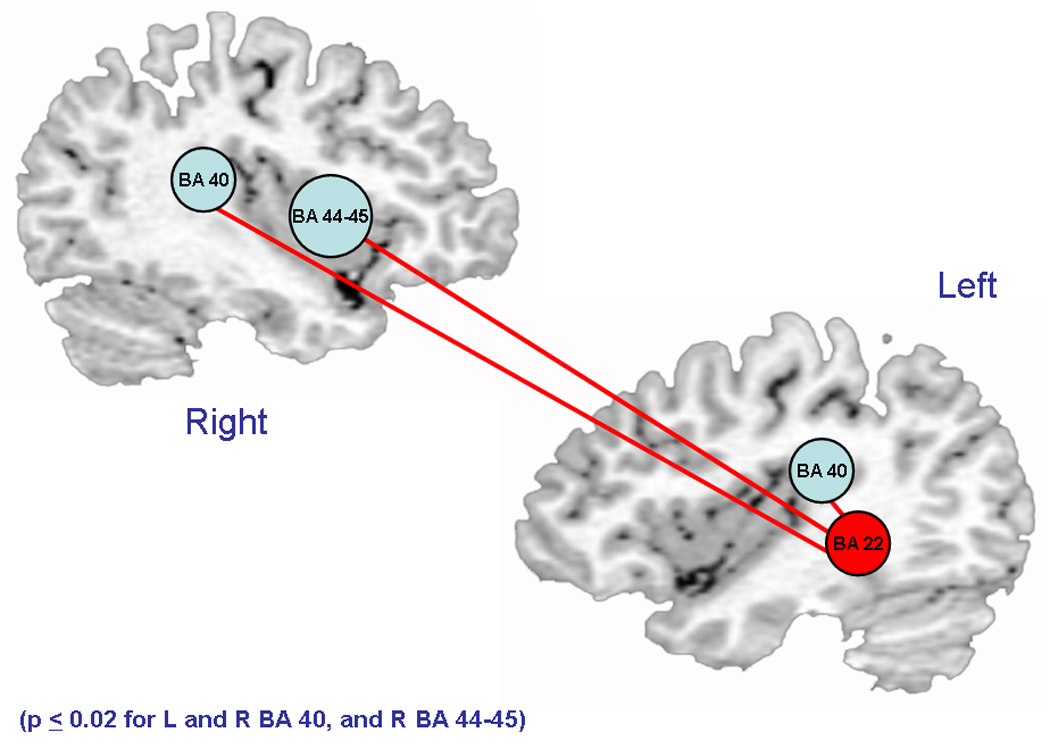

Group Connectivity Difference Maps

A map representing the reference time-course voxel-wise group differential connectivity (preterm – term controls) during language processing to Wernicke’s region is shown in Figure 2. Significant differences in activity between the reference region, and L BA 40, R BA 40, and R BA 44–45 (Broca’s homologue) were greater for the preterm group than the term controls (p ≤ 0.02 for all, Table 5).

Figure 2.

Increased connectivity to Wernicke’s region in PT children. Light blue circles represent regions with significantly increased connectivity to Wernicke’s region (red). Red lines represent connectivity between Wernicke’s region and bilateral BA 40 and R BA 44–45.

Table 5.

Effect of diagnosis (PT vs T) by region, after adjustment for VCIQ, age at scan and gender

| BA* Regions | R-square | P value§ |

|---|---|---|

| Left BA 21 | 0.069 | 1.00 |

| Right BA 21 | 0.035 | 1.00 |

| Right BA 22 | 0.109 | 0.22 |

| Left BA 39 | 0.102 | 1.00 |

| Right BA 39 | 0.086 | 0.22 |

| Left BA 40 | 0.190 | 0.01 |

| Right BA 40 | 0.141 | 0.02 |

| Left BA 44–45 | 0.110 | 0.33 |

| Right BA 44–45 | 0.140 | 0.02 |

| Left BA 47 | 0.052 | 1.00 |

| Right BA 47 | 0.030 | 1.00 |

BA Brodmann’s Area

Bonferroni corrected

Consideration of handedness

To investigate the role of handedness in our connectivity results, we investigated two strategies. First, we entered right-handedness (yes/no) into our GLM presented in the previous paragraph and in Table 5. This analysis is shown in Supplemental Table 1 and demonstrated no significant effects of handedness on our outcome data. Next, we repeated the GLM including only those subjects who were right hand dominant (data not shown). Similar to the GLM including right-handedness (yes/no), these data did not differ in significance from those shown in Table 5.

Perinatal Risk Factor Analyses

Secondary analyses were performed to examine those factors that have been associated with microstructural changes in the preterm brain. These include gender, birth weight, randomization to early indomethacin, and years of maternal education. General linear modeling analyses for those correlated regions that differentiated PT and T children demonstrated no significant differences between groups. Post-hoc correlations were run examining connectivity data by gender for the ROIs described with VCIQ, FSIQ and PPVT-R scores for all study subjects after adjusting for age at scan. No significant correlations were identified.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of connectivity between brain areas in preterm children and term controls at school age. Significantly different patterns of functional connectivity from Wernicke’s reference region were demonstrated in the preterm children compared to term controls with increased connectivity to right-sided regions seen in the preterm group. Wernicke’s region has been demonstrated to subserve language processing in numerous fMRI studies in both children and adults. (Brauer, 2007; Ment et al., 2006a) Independent of handedness of the study subjects, significantly greater correlations in activity were noted across hemispheres between the reference region and the SMG component of the inferior parietal lobule as well as the homologue of Broca’s area in the right inferior frontal gyrus, in the preterm group than in the term controls. A significantly increased ipsilateral connection between Wernicke’s and left SMG was also seen in preterm subjects. The left SMG, has traditionally been thought responsible for phonologic processing, (Ment et al., 2006a) and recent evidence has demonstrated the role of Broca’s area homologue in the right hemisphere in the auditory processing of language in young children. (Karunanayaka et al., 2007) Taken together, these data suggest the engagement of a broader network of neural systems for auditory phonologic processing of language in the prematurely born.

Although critical to our understanding of the developing brain, there are few reports of connectivity in the pediatric population. Recent studies of connectivity in typically developing subjects ranging in age from infancy to early adulthood have revealed emerging patterns of cortical maturation. Using connectivity analysis, investigators have described the differences that exist in the resting state networks of children, adolescents (Fair et al., 2008; Fair et al., 2007) and adults (Hampson et al., 2006a; Hampson et al., 2006b). Some resting state networks are present in infancy, (Fransson et al., 2007) and maturation of neural networks occurs during adolescence. (Fair et al., 2008; Fair et al., 2007) Over time, the developing brain increases the strength of connections that exist in spatially remote regions in an anterior-posterior direction, weaving distal brain areas into highly cohesive and connected circuits, while reducing the strength of connections between anatomically proximal regions and contralateral homologues. (Fair et al., 2008; Fair et al., 2007) Connectivity analysis in our study revealed an increase in cross-hemispheric connections in the preterm group with remarkable engagement of right-sided circuits such as Broca’s homologue and the SMG portion of the inferior parietal lobule. Given the developmental trajectories suggested by prior studies, it is possible that preterm children exhibit developmental delays in the maturation of their neural circuitry just as they appear to lag in the pruning of the initial overabundance of synapses in gray matter. (Kesler et al., 2004; Ment et al., 2008)

Alternatively, the engagement of right-sided regions in the connectivity circuit that includes Wernicke’s region in our preterm cohort may represent a compensatory strategy to overcome difficulties in language processing. Studies of dyslexic children have described similar findings and investigators hypothesized that disruption in the normal reading pathway results in the engagement of alternate systems to compensate for conventional circuit failure. (Shaywitz et al., 2002; Shaywitz, 2005) Recruitment of right hemispheric sites may allow children with reading difficulty to utilize other “perceptual processes to compensate for his or her poor phonologic skills.” (Shaywitz et al., 2002)

Although preterm children are at high risk for developmental disabilities, numerous recent studies have revealed a pattern of improvement in behavioral and neuropsychologic measures over time in the prematurely born. (Hack et al., 2005; Hack et al., 2002; Ment et al., 2003) In contrast, multiple MRI investigations have documented both volumetric and microstructural changes in the brains of preterm children during school age and adolescence. (Constable et al., 2008; Gimenez et al., 2006a; Kesler et al., 2004; Kesler et al., 2008; Nosarti et al., 2002; Reiss et al., 2004) Furthermore, recent evidence suggests that birth at early gestation has a long lasting influence on corticogenesis in preterm subjects compared to term controls during school age and early adolescence. (Kesler et al., 2004; Peterson et al., 2000; Reiss et al., 2004) Contradictions between the differences in cortical development and the recovery of cognitive function may be partially accounted for by our studies of connectivity. As has been reported for prematurely born teens and children with congenital focal brain lesions, neural plasticity may permit the recruitment of alternate pathways for language processing. (Chilosi et al., 2005; Rushe et al., 2004)

These data extend our previous work documenting the patterns of neural recovery and plasticity in the developing preterm brain. In the past, we have reported improved language scores over time in this cohort of prematurely born children compared to term controls. Earlier fMRI studies have shown that preterm children recruit alternate cortical regions in response to a passive listening task. (Ment et al., 2006b; Peterson et al., 2002) Furthermore, we have reported microstructural differences in the white matter tracts between those regions of the brain that sub-serve language processing. (Constable et al., 2008) The differences in functional connectivity reported in this paper represent the results of an important emerging modality available to investigate the alterations in language processing in preterm children.

The children who participated in this study are part of a well-studied cohort with neuroimaging available from the earliest postnatal hours. Sequential evaluation with a variety of imaging modalities has documented their progress in terms of cognitive performance, volumetric differences, cortical activation and microstructural alterations in normal cortical development over time. Although recent data in adult subjects suggest a correlation between structure and function, we had neither complete volumetric data nor diffusion tensor imaging in this cohort of children. (Olesen et al., 2003; Saur et al., 2008)

The limitations of this study include the small sample size. In addition, the use of fMRI to evaluate functional connectivity in this group is an emerging technology with little known about technical limitations. To the best of our knowledge this is the first study using functional connectivity to evaluate prematurely born children at school age. Longitudinal assessment of a large cohort of preterm and term controls is necessary to fully evaluate brain maturational changes and their effects on cognitive and language development.

In conclusion, these data demonstrate that preterm birth results in the engagement of alternate neural systems for language processing in the developing brain with increased recruitment of brain regions in the right hemisphere. These alterations may represent either a developmental lag in the stabilization of neural networks of prematurely born children, or the recruitment of alternate circuits for language in the developing preterm brain.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Deborah Hirtz and Walter Allan for their scientific expertise; Marjorene Ainley for follow-up coordination; Susan DeLancy and Victoria Watson for neurodevelopmental testing; and Hedy Sarofin and Terry Hickey for their technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by NS 27116, MO1-RR06022, MO1-RR00125, and T32 HD 07094

ABBREVIATIONS

- AC

Anterior cingulated

- AG

Angular gyrus

- BA

Brodmann’s area

- BOLD

Blood oxygen level dependent

- FSIQ

Full Scale Intelligence Quotient

- GLM

General linear model

- IFG

Inferior frontal gyrus

- IVH

Intraventricular hemorrhage

- IPL

Inferior parietal lobule

- PIAT-R

Peabody Individual Achievement Test - Revised

- PPVT-R

Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test - Revised

- PIQ

Performance Intelligence Quotient

- PT

Preterm

- PVL

Periventricular leukomalacia

- ROI

Region of interest

- SMG

Supramarginal gyrus

- STG

Superior temporal gyrus

- T

Term

- VCIQ

Verbal Comprehension Intelligence Quotient

- WISC - III

Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children - III

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Brauer JFA. Functional neural networks of semantic and syntactic processes in the developing brain. J Cogn Neurosci. 2007;19:1609–1623. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.10.1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilosi AM, Cipriani P, Brovedani P, Brizzolara D, Ferretti G, Pfanner L, Cioni G. Atypical language laterilization and early linguistic development in children with focal brain lesions. Devel Med Child Neurol. 2005;47:725–730. doi: 10.1017/S0012162205001532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constable RT, Ment LR, Vohr BR, Kesler SR, Fulbright RK, Lacadie C, DeLancy S, Katz KH, Schneider C, Schafer RJ, Makuch RW, Reiss AL. Prematurely born children demonstrate white matter microstructural differences at age 12 years relative to term controls: An investigation of group and gender effects. Pediatrics. 2008;121:306–316. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyet LE, Kennea NL, Counsell SJ, Maalouf EF, Ajayi-Obe M, Duggan PJ, Harrison MC, Allsop JM, Hajnal J, Herlihy AH, Edwards B, Laroches S, Cowan FM, Rutherford MA, Edwards AD. Natural history of brain lesions in extremely preterm infants studied with serial magnetic resonance imaging from birth and neurodevelopmental assessment. Pediatrics. 2006;118:536–548. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fair DA, Cohen AL, Dosenbach NUF, Church JA, Miezin FM, Barch DM, Raichle ME, Petersen SE, Schlaggar BL. The maturing architecture of the brain's default network. PNAS. 2008;105:4028–4032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800376105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fair DA, Dosenbach NUF, Church JA, Cohen AL, Brahmbhatt S, Miezin FM, Barch DM, Raichle ME, Petersen SE, Schlaggar BL. Development of distinct control networks through segregation and integration. PNAS. 2007;104:13507–13512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705843104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fransson P, Skiold B, Horsch S, Nordell A, Blennow M, Lagercrantz H, Aden U. Resting-state networks in the infant brain. PNAS. 2007;104:15531–15536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704380104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Williams S, Howard R, Frackowiak RS, Turner R. Movement-related effects in fMRI time-series. Magn Reson Med. 1996;35:346–355. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910350312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimenez M, Junque C, Narberhaus A, Bargallo N, Botet F, Mercader JM. White matter volume and concentration reductions in adolescents with history of very preterm birth: A voxel-based morphometry study. Neuroimage. 2006a;32:1485–1498. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimenez M, Junque C, Narberhaus A, Botet F, Bargallo N, Mercader JM. Correlations of thalamic reductions with verbal fluency impairment in those born prematurely. Neuroreport. 2006b;17:463–466. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000209008.93846.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimenez M, Junque C, Vendrell P, Caldu X, Narberhaus A, Bargallo N, Falcon C, Botet F, Mercader JM. Hippocampal functional magnetic resonance imaging during a face-name learning task in adolescents with antecedents of prematurity. Neuroimage. 2005;25:561–569. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hack M, Taylor HG, Drotar D, Schluchter M, Cartar L, Wilson-Costello D, Klein N, Friedman H, Mercuri-Minich N, Morrow M. Poor predictive validity of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development for cognitive function of extremely low birth weight children at school age. Pediatrics. 2005;116:333–341. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hack MB, Flannery DJ, Schluchter M, Cartar L, Borawski E, Klein N. Outcomes in young adulthood for very-low-birth-weight infants. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:149–157. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson M, Driesen NR, Skudlarski P, Gore JC, Constable RT. Brain connectivity related to working memory performance. J Neurosci. 2006a;26:1338–1343. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3408-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson M, Tokogl F, Sun Z, Schafer RJ, Skudlarski P, Gore JC, Constable RT. Connectivity - behavior analysis reveals that functional connectivity between left BA 39 and Broca's area varies with reading ability. NeuroImage. 2006b;31:513–519. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karunanayaka PR, Schmithorst VJ, Solodkin A, Chen EE, Szaflarski JP, Plate E. Age-related connectivity changes in fMRI data from children listening to stories. NeuroImage. 2007;34:349–360. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesler SR, Ment LR, Vohr B, Pajot SK, Schneider KC, Katz KH, Ebbitt TB, Duncan CC, Reiss AL. Volumetric analysis of regional cerebral development in preterm children. Pediatr Neurol. 2004;31:318–325. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesler SR, Reiss AL, Vohr B, Watson C, Schneider KC, Katz KH, Maller-Kesselman J, Silbereis J, Constable RT, Makuch RW, Ment LR. Brain volume reductions within multiple cognitive systems in male preterm children at age twelve. J Pediatr. 2008;152:513–520. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesler SR, Vohr B, Schneider KC, Katz KH, Makuch RW, Reiss AL, Ment LR. Increased temporal lobe gyrification in preterm children. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44:445–453. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamoorthy KS, Shannon DC, DeLong GE, Todres ID, Davis KR. Neurologic sequelae in the survivors of neonatal intraventricular hemorrhage. Pediatrics. 1979;64:233–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacadie CM, Fulbright RK, Rajeevan N, Constable RT, Papademetrix X. More accurate Talairach coordinates or neuroimaging using non-linear registration. NeuroImage. 2008;42:717–725. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.04.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMenamin JB, Shackelford GD, Volpe JJ. Outcome of neonatal intraventricular hemorrhage with periventricular echodense lesions. Ann Neurol. 1984;15:285–290. doi: 10.1002/ana.410150315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ment LR, Kesler SR, Vohr Katz KH, Baumgartner H, Schneider KC, Delancy S, Silbereis J, Duncan CC, Constable RT, Makuch RW, Reiss AL. Longitudinal brain volume changes in preterm and term control subjects during late childhood and adolescence. PEDIATRICS. 2009;123:503–511. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ment LR, Peterson BS, Meltzer JA, Vohr B, Allan WA, Katz KH, Lacadie C, Schneider KC, Duncan CC, Makuch RW, Constable RT. A functional MRI study of the long-term influences of early indomethacin exposure on language processing in the brains of prematurely born children. PEDIATRICS. 2006a;118:961–970. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ment LR, Peterson BS, Vohr B, Allan WA, Schneider C, Lacadie C, Katz KH, Maller-Kesselman J, Pugh KR, Duncan CC, Makuch RW, Constable RT. Cortical recruitment patterns in children born prematurely compared with control children druing a passive listening functional magnetic resonance imaging task. J Pediatr. 2006b;149:490–498. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ment LR, Vohr BR, Allan WA, Katz KH, Schneider C, Westerveld M, Duncan CC, Makuch RW. Change in cognitive function over time in very low-birth-weight infants. JAMA. 2003;289:705–711. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.6.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosarti C, M.H.S A-A, Frangou S, Stewart A, Rifkin L, Murray RM. Adolescents who were born very preterm have decreased brain volumes. Brain. 2002;125:1616–1623. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olesen PJ, Nagy Z, Westerberg H, Klingberg T. Combined analysis of DTI and fMRI data reveals a joint maturation of white and grey matter in a fronto-parietal network. Cognitive Brain Res. 2003;18:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson BS, Vohr B, Cannistraci CJ, Schneider KC, Katz KH, Westerveld M, Sparrow S, Anderson AW, Duncan CC, Makuch RW, Gore JC, Ment LR. Regional brain volume abnormalities and long-term cognitive outcome in preterm infants. JAMA. 2000;284:1939–1947. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.15.1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson BS, Vohr BR, Kane M, Whalen DH, Schneider KC, Katz KH, Zhang H, Duncan CC, Makuch RW, Gore JC, Ment LR. A functional MRI study of language processing and cognitive outcome in prematurely born children. Pediatrics. 2002;110:1153–1162. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.6.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss AL, Kesler SR, Vohr BR, Duncan CC, Katz KH, Pajot S, Schneider KC, Makuch RW, Ment LR. Sex differences in cerebral volumes of 8-year-olds born preterm. J Pediatr. 2004;145:242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushe TM, Temple CM, Rifkin L, Woodruff PWR, Bullmore ET, Stewart AL, Simmons AD, Russell TA, Murray RM. Lateralisation of language function in young adults born very preterm. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2004;89:F112–F118. doi: 10.1136/adc.2001.005314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saigal S, Stoskopf B, Streiner DL, Boyle M, Pinelli J, Paneth N, Goddeeris J. Transition of extremely low-birth-weight infants from adolescence to young adulthood. JAMA. 2006;295:667–675. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.6.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saur D, Kreher BW, Schnell S, Kummerer D, Kellmeyer P, Magnus-Sebastian Y, Umarova R, Musso M, Glauche V, Abel S, Huber W, Rijntjes M, Hennig J, Weiller C. Ventral and dorsal pathways for language. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18035–18040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805234105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaywitz BA, Shaywitz SE, Pugh KR, Mencl E, Fulbright RK, Skudlarski P, Constable RT, Marchione KE, Fletcher JM, Lyon GR, Gore JC. Disruption of posterior brain systems for reading in children with developmental dyslexia. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:101–110. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01365-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaywitz SE. Dyslexia (specific reading disability) Biol Psych. 2005;57:1301–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinnar S, Molteni RA, Gammon J, D'Souza BJ, Altman J, Freeman JM. Intraventicular hemorrhage in the premature infant. N Engl J Med. 1982;306:1464–1468. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198206173062406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver NC, Dunlap WP. Averaging correlation coefficients: Should Fisher's z transformation be used? J App Psychology. 1987;72:146–148. [Google Scholar]

- Skudlarski P, Jagannathan K, Calhoun VD, Hampson M, Skudlarski BA, Pearlson G. Measuring brain connectivity: Diffusion tensor imaging validates resting state temporal correlations. NeuroImage. 2008;43:445–461. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.07.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymonowicz W, Yu VYH, Bajuk B, Astbury J. Neurodevelopmental outcome of periventricular hemorrhage and leukomalacia in infants. Early Hum Dev. 1986;14:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(86)90164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward LJ, Anderson PJ, Austin NC, Howard K, Inder TE. Neonatal MRI to predict neurodevelopmental outcomes in preterm infants. New Engl J Med. 2006;355:685–694. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.