Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) causes chronic liver disease and affects an estimated 3% of the world's population. Options for the prevention or therapy of HCV infection are limited; there is no vaccine and the nonspecific, interferon-based treatments now in use are frequently ineffective and have significant side effects. A small-animal model for HCV infection would significantly expedite antiviral compound development and preclinical testing, as well as open new avenues to decipher the mechanisms that underlie viral pathogenesis. The natural species tropism of HCV is, however, limited to humans and chimpanzees. Here, we discuss the prospects of developing a mouse model for HCV infection, taking into consideration recent results on HCV entry and replication, and new prospects in xenotransplantation biology. We highlight three independent, but possibly complementary, approaches towards overcoming current species barriers and generating a small-animal model for HCV pathogenesis.

Keywords: hepatitis C virus, humanized mice, virus adaptation, entry, pathogenesis

See Glossary for abbreviations used in this article.

Glossary.

- CD

cluster of differentiation

claudin 1

hepatitis B virus

fumaryl acetoacetate hydrolase

microRNA

occludin

protein kinase R

scavenger receptor class B member 1

submergence induced protein-like factor

- CLDN1

claudin 1

hepatitis B virus

fumaryl acetoacetate hydrolase

microRNA

occludin

protein kinase R

scavenger receptor class B member 1

submergence induced protein-like factor

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

fumaryl acetoacetate hydrolase

microRNA

occludin

protein kinase R

scavenger receptor class B member 1

submergence induced protein-like factor

- FAH

fumaryl acetoacetate hydrolase

microRNA

occludin

protein kinase R

scavenger receptor class B member 1

submergence induced protein-like factor

- miRNA

microRNA

occludin

protein kinase R

scavenger receptor class B member 1

submergence induced protein-like factor

- OCLN

occludin

protein kinase R

scavenger receptor class B member 1

submergence induced protein-like factor

- PKR

protein kinase R

scavenger receptor class B member 1

submergence induced protein-like factor

- SCARB1

scavenger receptor class B member 1

submergence induced protein-like factor

- Sip-L

submergence induced protein-like factor

The need for a small animal model

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a hepatotropic pathogen of significant importance to public health. An estimated 130 million people worldwide are chronically infected and at risk of progression to cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma and end-stage liver disease. These sequelae make HCV infection the most common cause of liver transplantation (Brown, 2005). There is no HCV vaccine available, and the current treatment—which is a combination of PEGylated interferon (IFN)-α and ribavirin—is often ineffective and poorly tolerated (Zeuzem et al, 2009).

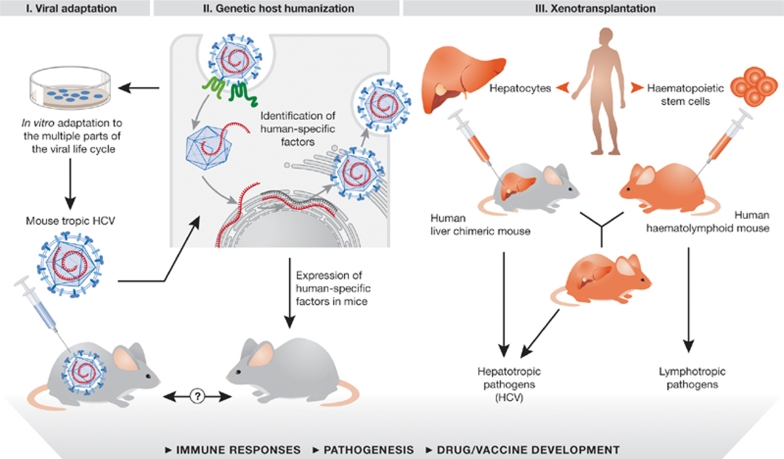

The development of additional preventive and therapeutic alternatives has been severely hampered by the lack of suitable animal models, a deficit resulting from the limited species tropism of HCV. Chimpanzees are the only available immunocompetent in vivo experimental system, but their use is limited by ethical concerns, restricted availability and prohibitively high costs (Bukh, 2004). An amenable small-animal model with exogenously introduced HCV susceptibility traits could significantly accelerate the preclinical testing of vaccine and drug candidates, as well as facilitate in vivo studies of HCV pathogenesis. Two alternative and not necessarily mutually exclusive approaches can be proposed to achieve this: the virus could be adapted to infect non-human cells, or rodent tissues could be humanized (Fig 1). The latter might be achieved either by xenotransplantation of human tissues, or by genetic manipulation to express or ablate key genes. Here, we discuss the progress and prospects towards developing small-animal models for HCV pathogenesis, with particular emphasis on the creation of an inbred mouse model.

Figure 1.

Strategies to create mouse models for HCV. Strategy I, viral adaptation; Strategy II, genetic host humanization; Strategy III, humanization by xenotransplantation. Refer to text for further details. HCV, hepatitis C virus.

HCV life cycle

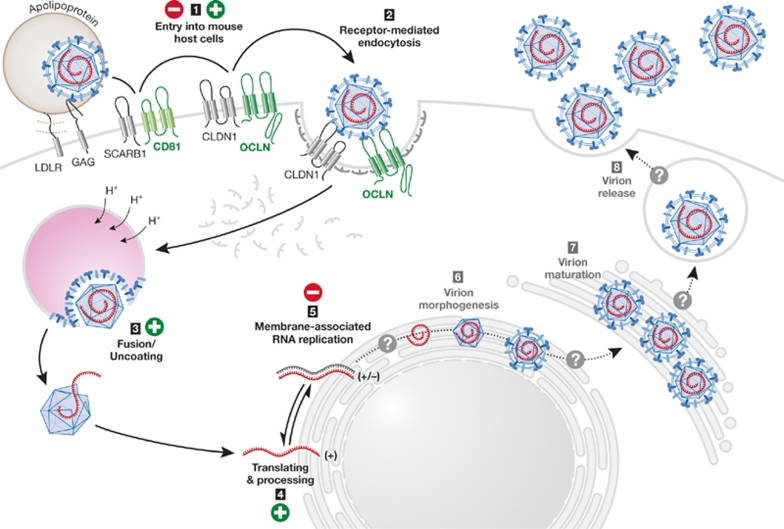

HCV is an enveloped virus with a positive-strand RNA genome. It was first discovered as the causative agent of non-A, non-B hepatitis in 1989 (Choo et al, 1989), and has since become amenable to cell culture studies of RNA replication—using subgenomic replicons—and entry—with HCV pseudoparticles (HCVpp). Most recently, it has become possible to study the entire viral life cycle in an HCV cell culture system (HCVcc; Bartenschlager & Sparacio, 2007; Tellinghuisen et al, 2007). HCV uses several host proteins to enter its target cell, the human hepatocyte (Fig 2); the minimal set of cell-specific uptake factors includes CD81 (Pileri et al, 1998), SCARB1 (Scarselli et al, 2002) and the tight junction molecules CLDN1 (Evans et al, 2007) and OCLN (Liu et al, 2009; Ploss et al, 2009). The internalization of the virion through receptor-mediated endocytosis is followed by the initiation of genome translation through an internal ribosome entry site. The virus encodes one long open reading frame, which generates a polyprotein that is processed into ten individual gene products by host-encoded and virally-encoded proteases (Moradpour et al, 2007).

Figure 2.

Blocks in HCV species tropism. Mouse cells inefficiently support the HCV life cycle. The expression of human CD81 and OCLN can overcome the block in entry, and HCV RNA translation is supported, whereas HCV RNA replication can only occur under selective pressure. Whether the late stages of the HCV life cycle (virion assembly and release) can take place in mouse cells is unclear. CD, cluster of differentiation; CLDN1, claudin 1; GAG, glycosaminoglycan; HCV, hepatitis C virus; LDLR, low density lipoprotein receptor; OCLN, occludin.

In addition, the HCV genome functions as the template for RNA-dependent RNA replication, which is a highly error-prone process. The final steps of the HCV life cycle are the least understood, as these have only recently become amenable to systematic study. The structural components of the virus—which are the core protein (C) and the envelope glycoproteins (E1 and E2)—and a growing number of non-structural proteins, including p7, NS2, NS3 and NS5A, have been implicated in the production of infectious virions (Murray et al, 2008). Infectious particles are thought to form by budding into the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum, followed by egress through the cellular secretory pathway. Many host factors might be required for these processes, and proteins involved in lipid metabolism are emerging as crucial players (Kapadia & Chisari, 2005; Miyanari et al, 2007; Ye, 2007).

Viral adaptation: generation of murine-tropic HCV

The inoculation of sera from HCV-infected individuals or of tissue-culture-derived virus into rodents—even into highly immunodeficient mice—does not result in detectable infection (A.P. and C.M.R., unpublished data). This resistance phenotype is probably multifactorial, but is at least partly attributable to a block in HCV entry. Although mouse SCARB1 and CLDN1 can mediate efficient HCVpp uptake, CD81 and OCLN must be of human origin to render mouse cells permissive to HCV infection (Ploss et al, 2009). The expression of mouse CD81 in human hepatoma cells (HepG2)—which lack endogenous expression of human CD81—can support HCV entry. However, the levels of infection are substantially lower (<15%) than in cells expressing primate and human CD81 orthologues, probably due to a reduced affinity between the HCV glycoproteins and mouse CD81 (Flint et al, 2006). Although mouse CD81 is more than 90% identical to the human protein, four positions that are crucial for the interaction with HCV E2—Ile 182, Asn 184, Phe 186 and Asp 196 (Higginbottom et al, 2000)—are not conserved in the murine sequence. HCV can, however, be adapted in vitro to use mouse CD81 (Bitzegeio & Pietschmann, 15th International Symposium on Hepatitis C Virus and Related Viruses, 2008, Abstract 24). The HCV glycoproteins have remarkable plasticity, as shown by the continuous escape of the virus from neutralizing antibodies over the course of chronic infection (von Hahn et al, 2007). This flexibility allowed the selection of three mutations in E1 and E2 after the serial passage of HCV on human cells that express only mouse CD81. Together, these changes enhanced mouse CD81-dependent uptake to levels comparable with infection using the human orthologue. A similar approach could be envisioned for the adaptation of HCV to entry through mouse OCLN, although it might not be so straightforward. Unlike the well-documented binding of E2 to CD81 (Pileri et al, 1998), it is not clear whether HCV interacts physically with OCLN. In addition, the adaptive mutations required for the use of mouse CD81 might not be compatible with the changes needed to allow the engagement of mouse OCLN. It is uncertain whether murine-tropic HCV would infect mouse hepatocytes as efficiently as human cells expressing the mouse entry factors on which it was selected, as mouse cells might lack necessary intracellular factors. However, ‘murinizing' the HCV glycoproteins could, in principle, produce a virus that efficiently enters mouse cells, thereby overcoming the first block to the viral life cycle (Fig 1).

The hydrodynamic transfection of HCV genomic RNA into the cytoplasm of mouse hepatocytes fails to initiate viral replication, indicating that an additional, post-entry restriction might exist (McCaffrey et al, 2002). Real-time imaging of firefly luciferase expression in living mice has shown that the HCV internal ribosome entry site is functional in mouse liver cells, indicating that this restriction occurs after initial translation (McCaffrey et al, 2002). HCV genomes that express antibiotic-selectable markers such as neomycin phosphotransferase can replicate in mouse hepatic cell lines (Uprichard et al, 2006; Zhu et al, 2003). The selection of similar HCV antibiotic-resistant replicons in human cell lines results in the appearance of adaptive mutations, which often significantly increase replication efficiency when re-engineered into the parental genome (Bartenschlager & Sparacio, 2007; Moradpour et al, 2007). Although mutations also occurred during replication of antibiotic-resistant HCV replicons in mouse cells, they seemed to be random rather than adaptive (Uprichard et al, 2006), as none significantly enhanced replication efficiency in the mouse cell environment when reintroduced into the parental subgenome (Zhu et al, 2003). This suggests that, although all essential cellular factors that support HCV replication are probably present in mouse cells, the virally encoded replication machinery might not mesh efficiently with the murine counterparts.

Drug selection is a proven strategy to establish HCV RNA replication in cells that are naturally less permissive, such as non-hepatic human and mouse cells; however, this approach cannot be translated easily to living animals due to broad toxicity. A possible solution could be the expression of a cDNA transgene that encodes the entire HCV genome, as is the case in HBV transgenic mice, which replicate and secrete HBV and have been crucial for the study of HBV immunobiology and pathogenesis (Chisari et al, 1985). The production of infectious HCV from stably HCV cDNA-transfected HepG2 has been reported (Cai et al, 2005). In this case, the generation of proper 5′ and 3′ ends of the HCV RNA genome is crucial to ensure efficient replication initiation. Although this approach is appealing, simply producing a greater abundance of replication-competent HCV RNA might not be sufficient to initiate and sustain replication in a mouse liver. To create a system for in vivo selection, an HCV genome expressing a heterologous selectable marker such as FAH could be used to complement a hepatotoxic FAH deficiency in engineered mice (Grompe et al, 1993), thereby taking advantage of the selective pressure that would be applied in vivo for HCV replication in FAH−/− mouse hepatocytes.

As highlighted above, previous studies have shown that HCV entry and replication can occur in an appropriate murine environment, but whether HCV virions can be assembled and released from mouse cells remains unknown. Mouse hepatoma cells harbouring a full-length HCV genome were found not to release infectious virus (Uprichard et al, 2006). However, this lack of virion production might be due to low levels of RNA accumulation, and it is possible that increasing viral replication will also allow the detection of infectious virus. If not, additional adaptation steps might be necessary to select for genomes with assembly competence in a mouse cell environment. Ideally, viral adaptation would culminate in a genome that recapitulates most or all of the viral life cycle in mouse cells, and would represent a significant step towards a readily available small-animal model for HCV (Fig 2). It should be considered, however, that any modifications affecting species tropism might also have significant effects on immune responses and pathogenesis, and that it is not clear which of the clinical features observed in humans would be recapitulated in such a model. Nonetheless, an easily accessible, cost-effective model would be useful for investigating at least some of the aspects of viral growth in vivo.

Host adaptation: xenotransplantation models

Adapting the murine environment to support the replication of wild-type HCV is an alternative approach that has already met with success. Chimeric mice that harbour HCV-permissive tissue can be obtained by transplanting human hepatocytes into mouse recipients with liver injury and severe immunodeficiency (Fig 1; Meuleman & Leroux-Roels, 2008). The most commonly used recipient strain is a urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) transgenic mouse, in which transgene expression in the liver is driven by an albumin (Alb) promoter. The Alb-uPA transgene overexpression is hepatotoxic and results in homozygous mice with severe liver damage (Heckel et al, 1990), which can be rescued by transplanting non-transgenic (human) hepatocytes. These chimeric-liver mice are susceptible to human hepatotropic pathogens, including HBV and HCV, as well as the malaria parasite (Dandri et al, 2001; Mercer et al, 2001; Morosan et al, 2006). The inoculation of HCVcc or sera from HCV-positive patients into these mice leads to a rapid increase in viraemia, which is sustained over several weeks (Lindenbach et al, 2006; Mercer et al, 2001; Meuleman et al, 2005).

Xenotransplanted humanized mice hold great potential as a means of assessing drug and vaccine efficacy (Meuleman & Leroux-Roels, 2008). For example, they were used to show that in vivo HCV infection can be prevented with antibodies directed against CD81 (Meuleman et al, 2008), as well as with polyclonal antibodies obtained from a chronically infected patient (Vanwolleghem et al, 2008). Such chimeric mice have also been used for the study of pharmacokinetics and drug toxicity (Katoh et al, 2008) and, in fact, accurately reproduce the toxicological features of the HCV protease inhibitor BILN 2061 (Vanwolleghem et al, 2007), a compound that was withdrawn from clinical development because of the occurrence of cardiotoxic side effects in primates.

Unfortunately, chimeric-liver mice can be produced only in small numbers, and their use is limited by logistical constraints and substantial variability. It might be possible to overcome some of these issues by using alternative liver injury models, such as animals with a targeted FAH disruption, which have already been successfully engrafted with human hepatocytes (Azuma et al, 2007; Bissig et al, 2007) but have not yet been shown to be susceptible to HCV or HBV. Pathogenesis and immunity studies are also limited in liver chimeric mice, as the animals lack a functional immune system—which is required to avoid the rejection of the xenograft. To overcome this problem, substantial efforts are under way to combine humanized liver models with mice harbouring a human haematolymphoid system (Fig 2; Legrand et al, 2009). These mice are generated by engrafting suspensions of human haematopoietic progenitor stem cells into immunodeficient animals; after successful human immune reconstitution, these animals can elicit virus-specific immune responses (Legrand et al, 2009; Strowig et al, 2009). Merging hepatic and haematolymphoid reconstitution in a single recipient will allow studies of pathogenesis, immune correlates and mechanisms of persistence of HCV and other human hepatotropic pathogens (Fig 2). These xenograft models provide a unique opportunity to study HCV biology in human hepatocytes and to monitor human immune responses in vivo. However, the generation of these types of humanized mice requires substantial infrastructure and advanced technical skills. The scarcity of adequate human primary material remains a significant logistical challenge. Therefore, it will be crucial to improve the distribution of available material and to develop reproducible and robust protocols for the in vitro expansion or differentiation of hepatocytes and haematopoietic progenitor stem cells from renewable sources, such as embryonic or induced pluripotent stem cells.

Host adaptation: a genetic approach

An inbred mouse model with inheritable susceptibility to HCV would overcome the technical difficulties of the xenotransplantation model. The challenge is to systematically identify and overcome any restrictions to HCV growth in mouse cells. At the level of pathogen entry, there are precedents for the successful genetic humanization of receptors and/or co-receptors in mouse cells for other human pathogens, such as poliovirus (CD155; Racaniello & Ren, 1994), measles virus (CD46/CD150; Sellin & Horvat, 2009), human coronavirus (CD13; Lassnig et al, 2005), human immunodeficiency virus (CD4/CCR5/CXCR4; Klotman & Notkins, 1996) and Listeria monocytogenes (Lecuit et al, 2001). After the discovery of CD81 as an essential HCV entry factor (Pileri et al, 1998), transgenic mice expressing the human protein in a wide variety of tissues were produced (Masciopinto et al, 2002). However, although the binding of recombinant E2 to liver, thymocytes and splenic lymphocytes was increased in comparison to non-transgenic controls, human CD81-transgenic mice were resistant to HCV infection. This led to the conclusion that the expression of human CD81 alone is insufficient to confer susceptibility to HCV infection in mice. Enthusiasm for creating an inbred mouse model for HCV has recently been rekindled by the identification of OCLN as the second human factor that is essential to overcome the cross-species barrier at the level of entry (Ploss et al, 2009). However, to accurately reproduce the complex process of HCV entry in vivo, it will be important to achieve native expression patterns of the human HCV entry factor orthologues. Advances in mouse genetics, including bacterial artificial chromosome transgenics and knock-in approaches, will undoubtedly be crucial in achieving this. Such a model would allow HCV-glycoprotein-mediated entry in an inbred mouse strain, and would be an invaluable tool for analysing HCV entry in vivo and for preclinical testing of new intervention strategies (Fig 2).

Although the minimal human factors that are crucial for viral uptake have been defined, the essential host factors required for replication are less clear. Human Sip-L has been reported to increase HCV replication in otherwise non-permissive cell lines, such as HepG2 and HEK293T (Yeh et al, 2001), and was subsequently shown to slightly enhance replication in a mouse hepatoma cell line (Hepa1.6) that expresses human CD81 (Yeh et al, 2008). However, the list of cellular components that are implicated in HCV replication is still growing (Table 1; Ng et al, 2007; Randall et al, 2007; Supekova et al, 2008; Tai et al, 2009; Vaillancourt et al, 2009; Wang et al, 2005; Watashi et al, 2005). Unfortunately, independent studies often have minimal overlap and the relevance of many of these interactions to HCV biology remains to be demonstrated. Although the amino-acid sequences of most of these proteins are conserved between mice and humans, it is possible that divergence of crucial functional domains will reduce the capacity of certain murine factors to support HCV replication. A comprehensive gain-of-function analysis of individual human genes in mouse cells has not yet been completed. Alternatively, a functional cDNA complementation screen could be a less biased approach to identify specific human factors that are required for efficient HCV RNA replication in mouse cells. However, such a screen would be particularly challenging if more than one gene is required to establish efficient replication.

Table 1.

Cellular factors with potential roles in hepatitis C virus replication

| Gene | Protein | Approximate reduction of HCV RNA replication (%) | Sequence identity (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAMP | Hepcidin antimicrobial peptide | 80 | 58.3 | Tai et al, 2009 |

| LTB | Lymphotoxin-β | 80 | 60.0 | Ng et al, 2007 |

| TBXA2R | Thromboxane A2 receptor | 80 | 75.1 | Ng et al, 2007 |

| VAPA | Vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein A | n/a | 82.3 | Gao et al, 2004 |

| NUAK2 | NUAK family, SNF1-like kinase, 2 | 61 | 85.7 | Ng et al, 2007 |

| TRAF2 | TNF receptor-associated factor 2 | 65 | 86.8 | Ng et al, 2007 |

| VRK1 | Vaccinia-related kinase 1 | 50 | 87.1 | Supekova et al, 2008 |

| MAP2K7 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 7 | 80 | 88.0 | Ng et al, 2007 |

| RelA | V-rel reticuloendotheliosis viral oncogene homologue A | 80 | 88.6 | Ng et al, 2007 |

| VAPB | Vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein B and C | n/a | 90.1 | Hamamoto et al, 2005; Kukihara et al, 2009 |

| NFKB2 | Nuclear factor of κ light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells 2 (p49/p100) | 80 | 91.8 | Ng et al, 2007 |

| DICER1 | Endoribonuclease Dicer | >85 | 92.0 | Randall et al, 2007 |

| JAK1 | Janus kinase 1 | 50 | 94.7 | Supekova et al, 2008 |

| SLC12A5 | Solute carrier family 12 (potassium/chloride transporters), member 5 | >90 | 95.3 | Ng et al, 2007 |

| FBXL2 | F-box and leucine-rich repeat protein 2 | 65 | 95.7 | Wang et al, 2005 |

| SLC12A4 | Solute carrier family 12 (potassium/chloride transporters), member 4 | >90 | 96.2 | Ng et al, 2007 |

| PI4KA | Phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase, catalytic, α | >80 | 97.7 | Vaillancourt et al, 2009; Tai et al, 2009 |

| DDX3X | DEAD box protein 3, X-chromosomal | >95 | 98.0 | Randall et al, 2007 |

| PPIA | Peptidylprolyl isomerase A; cyclophilin A | >99 | 98.2 | Kaul et al, 2009; Yang et al, 2008 |

| EIF2S3 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2, subunit 3; eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 subunit γ (eIF-2-γ) | >95 | 99.0 | Randall et al, 2007 |

| CSK | c-src tyrosine kinase | 60 | 99.1 | Supekova et al, 2008 |

| CDC42 | Cell division cycle 42 (GTP-binding protein, 25 kDa) | >60 | 100.0 | Berger et al, 2009 |

| COPZ1 | Coatomer protein complex, subunit ζ 1 | ca. 90 | 100.0 | Tai et al, 2009 |

These studies have provided quantitative information about the impact of loss-of-function experiments on HCV replication. The reduction of replication was generally achieved by silencing the cellular transcripts with short interfering RNA. The factors included here are those that the authors of each study have highlighted as their top hits. Genes are placed in inverse order of similarity between the human and mouse orthologues. HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Cellular miRNAs can also profoundly influence virus replication and pathogenesis (Gottwein & Cullen, 2008). Two liver-specific miRNAs—miR122 and miR199a*—have been shown to affect HCV RNA translation and replication (Jopling et al, 2005, 2008; Murakami et al, 2009). Mouse miR122 and miR199* are identical in sequence and show similar expression levels to their human counterparts (Chang et al, 2004); however, slight sequence divergence or a differential abundance of other miRNAs with seed sites in the HCV genome might affect tropism (Pedersen et al, 2007).

In addition to missing or incompatible positive regulators of HCV replication, dominant-negative restriction factors might be present in mouse cells. Altered or exacerbated innate antiviral responses, the inability of HCV proteins to overcome murine defences, or mouse-specific restriction factors similar to those that control retroviral infection—such as Fv1, TRIM5α or APOBEC3 cytidine deaminases—could impair HCV replication in mouse cells. Variations in the type or intensity of the antiviral response between hosts is known to restrict the tropism of certain viruses, such as myxoma virus, which is only permissive in mouse cells that have impaired IFN responses (Werden et al, 2008). The induction of type I IFNs is also extremely important for cellular defence against HCV, and is counteracted by the cleavage of several host proteins by the viral serine protease (Keller et al, 2007). In agreement with this, subgenomic HCV RNA was shown to replicate more efficiently in PKR-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts than in wild-type cells (Chang et al, 2006).

In summary, due to the limited capacity of mouse cells to support the HCV life cycle, several genetic adaptations to humanize the murine host are required to create an inbred mouse model for HCV infection. In addition, combining these humanizations with mouse strains that harbour a targeted downregulation of key molecules involved in antiviral signalling could create an environment that is more suitable to initiate and sustain viral replication (Fig 2). Although genetic disruption of the molecules that are critical for mediating antiviral responses probably alters immunity and pathogenesis, an inbred mouse model of sustained HCV infection could be a platform for further improvements designed to mimic more closely the clinical features of human hepatitis.

Conclusions

Hepatitis C is a complex medical problem that is aggravated by the insufficient efficacy and global accessibility of current standard-of-care medications and by the lack of a vaccine to achieve widespread protection. A robust animal model that can be easily propagated and that recapitulates all or part of the viral life cycle would not only be instrumental in improving our understanding of HCV pathogenesis, but would also help to guide drug and vaccine development (Sidebar A). Furthermore, the ability to model liver disease progression is crucial for devising new intervention strategies that are able to slow down or even reverse liver cirrhosis and fibrosis. It is probable that deciphering the barriers to HCV replication in mouse cells will provide rich insight into virus–host interactions and create a blueprint for a robust mouse model of HCV infection.

Sidebar A | In need of answers.

What is the composition of an infectious virion (structure, viral and host proteins)?

Does HCV have regulated gene expression? If so, what steps in the HCV life cycle are subject to regulation?

Is there a particular spatiotemporal engagement of cellular HCV entry factors?

Which cellular factors participate in HCV RNA replication and virus assembly?

What determines HCV tissue and species tropism?

What host and viral mechanisms are involved in viral clearance and maintaining viral persistence? What are the mechanisms of disease progression?

Can immune responses be primed or stimulated in naive or chronically infected individuals to eliminate the virus? If so, can this information be used to create a therapeutic or preventive vaccine? How would an HCV vaccine be deployed and who would receive it?

Is the liver the only natural reservoir for HCV replication? How does HCV spread in the liver? What is the phenotype of HCV-infected hepatocytes compared with uninfected bystander cells?

Can drugs targeting viral proteins and/or cellular cofactors required for replication lead to an effective treatment for all HCV genotypes?

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Murray (The Rockefeller University) for editing the manuscript and A. Branch (Mount Sinai School of Medicine) and I.M. Jacobson for useful discussions. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 AI072613) and Gates Foundation through the Grand Challenges in Global Health initiative, and funded in part by the Greenberg Medical Research Institute, the Ellison Medical Foundation, the Starr Foundation, the Ronald A. Shellow Memorial Fund and the Richard Salomon Family Foundation (to C.M.R.). C.M.R. is an Ellison Medical Foundation Senior Scholar in Global Infectious Diseases. A.P. is the recipient of a Kimberly Lawrence-Netter Cancer Research Discovery Fund Award.

References

- Azuma H, Paulk N, Ranade A, Dorrell C, Al-Dhalimy M, Ellis E, Strom S, Kay MA, Finegold M, Grompe M (2007) Robust expansion of human hepatocytes in Fah−/−/Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− mice. Nat Biotechnol 25: 903–910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartenschlager R, Sparacio S (2007) Hepatitis C virus molecular clones and their replication capacity in vivo and in cell culture. Virus Res 127: 195–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger KL, Cooper JD, Heaton NS, Yoon R, Oakland TE, Jordan TX, Mateu G, Grakoui A, Randall G (2009) Roles for endocytic trafficking and phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase III alpha in hepatitis C virus replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 7577–7582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissig KD, Le TT, Woods NB, Verma IM (2007) Repopulation of adult and neonatal mice with human hepatocytes: a chimeric animal model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 20507–20511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RS Jr (2005) Hepatitis C and liver transplantation. Nature 436: 973–978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukh J (2004) A critical role for the chimpanzee model in the study of hepatitis C. Hepatology 39: 1469–1475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z, Zhang C, Chang KS, Jiang J, Ahn BC, Wakita T, Liang TJ, Luo G (2005) Robust production of infectious hepatitis C virus (HCV) from stably HCV cDNA-transfected human hepatoma cells. J Virol 79: 13963–13973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J et al. (2004) miR-122, a mammalian liver-specific microRNA, is processed from hcr mRNA and may downregulate the high affinity cationic amino acid transporter CAT-1. RNA Biol 1: 106–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang KS, Cai Z, Zhang C, Sen GC, Williams BR, Luo G (2006) Replication of hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA in mouse embryonic fibroblasts: protein kinase R (PKR)-dependent and PKR-independent mechanisms for controlling HCV RNA replication and mediating interferon activities. J Virol 80: 7364–7374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisari FV, Pinkert CA, Milich DR, Filippi P, McLachlan A, Palmiter RD, Brinster RL (1985) A transgenic mouse model of the chronic hepatitis B surface antigen carrier state. Science 230: 1157–1160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choo QL, Kuo G, Weiner AJ, Overby LR, Bradley DW, Houghton M (1989) Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome. Science 244: 359–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dandri M et al. (2001) Repopulation of mouse liver with human hepatocytes and in vivo infection with hepatitis B virus. Hepatology 33: 981–988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans MJ, von Hahn T, Tscherne DM, Syder AJ, Panis M, Wolk B, Hatziioannou T, McKeating JA, Bieniasz PD, Rice CM (2007) Claudin-1 is a hepatitis C virus co-receptor required for a late step in entry. Nature 446: 801–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint M, von Hahn T, Zhang J, Farquhar M, Jones CT, Balfe P, Rice CM, McKeating JA (2006) Diverse CD81 proteins support hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol 80: 11331–11342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L, Aizaki H, He JW, Lai MM (2004) Interactions between viral non-structural proteins and host protein hVAP-33 mediate the formation of hepatitis C virus RNA replication complex on lipid raft. J Virol 78: 3480–3488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottwein E, Cullen BR (2008) Viral and cellular microRNAs as determinants of viral pathogenesis and immunity. Cell Host Microbe 3: 375–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grompe M, al-Dhalimy M, Finegold M, Ou CN, Burlingame T, Kennaway NG, Soriano P (1993) Loss of fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase is responsible for the neonatal hepatic dysfunction phenotype of lethal albino mice. Genes Dev 7: 2298–2307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamamoto I et al. (2005) Human VAP-B is involved in hepatitis C virus replication through interaction with NS5A and NS5B. J Virol 79: 13473–13482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckel JL, Sandgren EP, Degen JL, Palmiter RD, Brinster RL (1990) Neonatal bleeding in transgenic mice expressing urokinase-type plasminogen activator. Cell 62: 447–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higginbottom A, Quinn ER, Kuo CC, Flint M, Wilson LH, Bianchi E, Nicosia A, Monk PN, McKeating JA, Levy S (2000) Identification of amino acid residues in CD81 critical for interaction with hepatitis C virus envelope glycoprotein E2. J Virol 74: 3642–3649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jopling CL, Yi M, Lancaster AM, Lemon SM, Sarnow P (2005) Modulation of hepatitis C virus RNA abundance by a liver-specific microRNA. Science 309: 1577–1581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jopling CL, Schutz S, Sarnow P (2008) Position-dependent function for a tandem microRNA miR-122-binding site located in the hepatitis C virus RNA genome. Cell Host Microbe 4: 77–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapadia SB, Chisari FV (2005) Hepatitis C virus RNA replication is regulated by host geranylgeranylation and fatty acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 2561–2566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh M, Tateno C, Yoshizato K, Yokoi T (2008) Chimeric mice with humanized liver. Toxicology 246: 9–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul A, Stauffer S, Berger C, Pertel T, Schmitt J, Kallis S, Lopez MZ, Lohmann V, Luban J, Bartenschlager R (2009) Essential role of cyclophilin A for hepatitis C virus replication and virus production and possible link to polyprotein cleavage kinetics. PLoS Pathog 5: e1000546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller BC, Johnson CL, Erickson AK, Gale M Jr (2007) Innate immune evasion by hepatitis C virus and West Nile virus. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 18: 535–544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotman PE, Notkins AL (1996) Transgenic models of human immunodeficiency virus type-1. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 206: 197–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukihara H et al. (2009) Human VAP-C negatively regulates hepatitis C virus propagation. J Virol 83: 7959–7969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassnig C, Kolb A, Strobl B, Enjuanes L, Muller M (2005) Studying human pathogens in animal models: fine tuning the humanized mouse. Transgenic Res 14: 803–806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecuit M, Vandormael-Pournin S, Lefort J, Huerre M, Gounon P, Dupuy C, Babinet C, Cossart P (2001) A transgenic model for listeriosis: role of internalin in crossing the intestinal barrier. Science 292: 1722–1725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legrand N et al. (2009) Humanized mice for modeling human infectious disease: challenges, progress, and outlook. Cell Host Microbe 6: 5–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenbach BD et al. (2006) Cell culture-grown hepatitis C virus is infectious in vivo and can be recultured in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 3805–3809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Yang W, Shen L, Turner JR, Coyne CB, Wang T (2009) Tight junction proteins claudin-1 and occludin control hepatitis C virus entry and are downregulated during infection to prevent superinfection. J Virol 83: 2011–2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masciopinto F, Freer G, Burgio VL, Levy S, Galli-Stampino L, Bendinelli M, Houghton M, Abrignani S, Uematsu Y (2002) Expression of human CD81 in transgenic mice does not confer susceptibility to hepatitis C virus infection. Virology 304: 187–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaffrey AP, Ohashi K, Meuse L, Shen S, Lancaster AM, Lukavsky PJ, Sarnow P, Kay MA (2002) Determinants of hepatitis C translational initiation in vitro, in cultured cells and mice. Mol Ther 5: 676–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer DF et al. (2001) Hepatitis C virus replication in mice with chimeric human livers. Nat Med 7: 927–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuleman P, Hesselgesser J, Paulson M, Vanwolleghem T, Desombere I, Reiser H, Leroux-Roels G (2008) Anti-CD81 antibodies can prevent a hepatitis C virus infection in vivo. Hepatology 48: 1761–1768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuleman P, Leroux-Roels G (2008) The human liver-uPA-SCID mouse: A model for the evaluation of antiviral compounds against HBV and HCV. Antiviral Res 80: 231–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuleman P, Libbrecht L, De Vos R, de Hemptinne B, Gevaert K, Vandekerckhove J, Roskams T, Leroux-Roels G (2005) Morphological and biochemical characterization of a human liver in a uPA-SCID mouse chimera. Hepatology 41: 847–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyanari Y, Atsuzawa K, Usuda N, Watashi K, Hishiki T, Zayas M, Bartenschlager R, Wakita T, Hijikata M, Shimotohno K (2007) The lipid droplet is an important organelle for hepatitis C virus production. Nat Cell Biol 9: 1089–1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moradpour D, Penin F, Rice CM (2007) Replication of hepatitis C virus. Nat Rev Microbiol 5: 453–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morosan S et al. (2006) Liver-stage development of Plasmodium falciparum, in a humanized mouse model. J Infect Dis 193: 996–1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami Y, Aly HH, Tajima A, Inoue I, Shimotohno K (2009) Regulation of the hepatitis C virus genome replication by miR-199a. J Hepatol 50: 453–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CL, Jones CT, Rice CM (2008) Architects of assembly: roles of Flaviviridae non-structural proteins in virion morphogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 6: 699–708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng TI et al. (2007) Identification of host genes involved in hepatitis C virus replication by small interfering RNA technology. Hepatology 45: 1413–1421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen IM, Cheng G, Wieland S, Volinia S, Croce CM, Chisari FV, David M (2007) Interferon modulation of cellular microRNAs as an antiviral mechanism. Nature 449: 919–922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pileri P et al. (1998) Binding of hepatitis C virus to CD81. Science 282: 938–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploss A, Evans MJ, Gaysinskaya VA, Panis M, You H, de Jong YP, Rice CM (2009) Human occludin is a hepatitis C virus entry factor required for infection of mouse cells. Nature 457: 882–886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racaniello VR, Ren R (1994) Transgenic mice and the pathogenesis of poliomyelitis. Arch Virol Suppl 9: 79–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall G et al. (2007) Cellular cofactors affecting hepatitis C virus infection and replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 12884–12889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarselli E, Ansuini H, Cerino R, Roccasecca RM, Acali S, Filocamo G, Traboni C, Nicosia A, Cortese R, Vitelli A (2002) The human scavenger receptor class B type I is a novel candidate receptor for the hepatitis C virus. EMBO J 21: 5017–5025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellin CI, Horvat B (2009) Current animal models: transgenic animal models for the study of measles pathogenesis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 330: 111–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strowig T et al. (2009) Priming of protective T cell responses against virus-induced tumors in mice with human immune system components. J Exp Med 206: 1423–1434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supekova L, Supek F, Lee J, Chen S, Gray N, Pezacki JP, Schlapbach A, Schultz PG (2008) Identification of human kinases involved in hepatitis C virus replication by small interference RNA library screening. J Biol Chem 283: 29–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai AW, Benita Y, Peng LF, Kim SS, Sakamoto N, Xavier RJ, Chung RT (2009) A functional genomic screen identifies cellular cofactors of hepatitis C virus replication. Cell Host Microbe 5: 298–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tellinghuisen TL, Evans MJ, von Hahn T, You S, Rice CM (2007) Studying hepatitis C virus: making the best of a bad virus. J Virol 81: 8853–8867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uprichard SL, Chung J, Chisari FV, Wakita T (2006) Replication of a hepatitis C virus replicon clone in mouse cells. Virol J 3: 89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillancourt FH, Pilote L, Cartier M, Lippens J, Liuzzi M, Bethell RC, Cordingley MG, Kukolj G (2009) Identification of a lipid kinase as a host factor involved in hepatitis C virus RNA replication. Virology 387: 5–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanwolleghem T, Bukh J, Meuleman P, Desombere I, Meunier JC, Alter H, Purcell RH, Leroux-Roels G (2008) Polyclonal immunoglobulins from a chronic hepatitis C virus patient protect human liver-chimeric mice from infection with a homologous hepatitis C virus strain. Hepatology 47: 1846–1855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanwolleghem T, Meuleman P, Libbrecht L, Roskams T, De Vos R, Leroux-Roels G (2007) Ultra-rapid cardiotoxicity of the hepatitis C virus protease inhibitor BILN 2061 in the urokinase-type plasminogen activator mouse. Gastroenterology 133: 1144–1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Hahn T, Yoon JC, Alter H, Rice CM, Rehermann B, Balfe P, McKeating JA (2007) Hepatitis C virus continuously escapes from neutralizing antibody and T-cell responses during chronic infection in vivo. Gastroenterology 132: 667–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Gale M Jr, Keller BC, Huang H, Brown MS, Goldstein JL, Ye J (2005) Identification of FBL2 as a geranylgeranylated cellular protein required for hepatitis C virus RNA replication. Mol Cell 18: 425–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watashi K, Ishii N, Hijikata M, Inoue D, Murata T, Miyanari Y, Shimotohno K (2005) Cyclophilin B is a functional regulator of hepatitis C virus RNA polymerase. Mol Cell 19: 111–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werden SJ, Rahman MM, McFadden G (2008) Poxvirus host range genes. Adv Virus Res 71: 135–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Robotham JM, Nelson HB, Irsigler A, Kenworthy R, Tang H (2008) Cyclophilin A is an essential cofactor for hepatitis C virus infection and the principal mediator of cyclosporine resistance in vitro. J Virol 82: 5269–5278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J (2007) Reliance of host cholesterol metabolic pathways for the life cycle of hepatitis C virus. PLoS Pathog 3: e108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh CT, Lai HY, Chen TC, Chu CM, Liaw YF (2001) Identification of a hepatic factor capable of supporting hepatitis C virus replication in a nonpermissive cell line. J Virol 75: 11017–11024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh CT, Lai HY, Yeh YJ, Cheng JC (2008) Hepatitis C virus infection in mouse hepatoma cells co-expressing human CD81 and Sip-L. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 372: 157–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeuzem S, Berg T, Moeller B, Hinrichsen H, Mauss S, Wedemeyer H, Sarrazin C, Hueppe D, Zehnter E, Manns MP (2009) Expert opinion on the treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Viral Hepat 16: 75–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Q, Guo JT, Seeger C (2003) Replication of hepatitis C virus subgenomes in nonhepatic epithelial and mouse hepatoma cells. J Virol 77: 9204–9210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Alexander Ploss & Charles M. Rice

Alexander Ploss & Charles M. Rice