Abstract

The two fundamental lineages of photoreceptor cells, microvillar and ciliary, were long thought to be a prerogative of invertebrate and vertebrate organisms, respectively. However evidence of their ancient origin, preceding the divergence of these two branches of metazoa, suggests instead that they should be ubiquitously distributed. Melanopsin-expressing ‘circadian’ light receptors may represent the remnants of the microvillar photo- receptors amongst vertebrates, but they lack the characteristic architecture of this lineage, and much remains to be clarified about their signaling mechanisms. Hesse and Joseph cells of the neuronal tube of amphioxus (Branchiostoma fl.)—the most basal chordate extant—turn out to be depolarizing primary microvillar photoreceptors, that generate a melanopsin-initiated, PLC-dependent response to light, mobilizing internal Ca and increasing a membrane conductance selective to Na and Ca ions. As such, they represent a canonical instance of invertebrate-like visual cells in the chordate phylum.

Key words: amphioxus, melanopsin, photoreceptors, light transduction, vision evolution

The structural diversity of visual organs in animals is staggering, but at the level of photoreceptor cells things become simpler, and one encounters just a two-way partition defined by the structure of the light-sensing organelle: this is either comprised of microvilli, short infoldings of the apical membrane packed with actin filaments, or else it arises from a modified cilium, with its characteristic radial arrangement of microtubules.1 These two cell types also differ radically in the biochemical scheme they have developed to couple photon absorption to the changes in ionic conductances that convert it into an electrical signal: invariably, microvillar receptors utilize phospholipase C (PLC) and phosophoinositide-based lipid signaling,2 whereas ciliary receptors mobilize cyclic nucleotides.3,4

Traditionally, it was thought that this distinction was tightly associated with taxonomy—vertebrate retinas being comprised of ciliary receptors, and microvillar photoreceptors being strictly segregated to the eyes of invertebrates.1 This vertebrate-invertebrate dichotomy is a puzzle in the light of the discovery, among others, of putative photoreceptors of the microvillar type in plathyelminthes5 and both ciliary and microvillar in cnidaria6 (see Fig. 1). The presence of both classes of visual cells even in pre-bilateria implies that their origin must date back to a time preceding the separation of protostomia and deuterostomia. Therefore, descendants of both lineages of visual cells ought to be represented across the two branches. Indeed, bona fide ciliary photoreceptors have been studied in a few marine mollusks7,8 and likely candidates have been described in a growing number of other invertebrates,9,10 although their alleged light sensitivity is yet to be corroborated physiologically. By contrast, their counterparts, microvillar receptors, were never found in vertebrates.

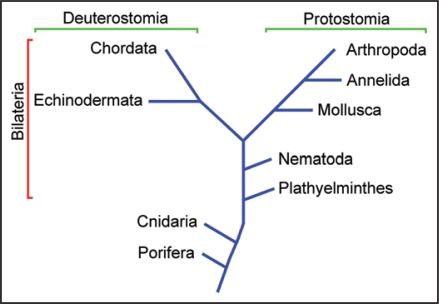

Figure 1.

Simplified phylogenetic tree. Ciliary photoreceptors are typical of vertebrata (in the chordata phylum), whereas microvillar photoreceptors have been extensively characterized both morphologically and physiologically in arthropoda and mollusca. However, putative photoreceptors of both types have subsequently been identified also in pre-bilateria, such as box jellyfish (cnidaria).

The situation changed with the discovery that the retina of mammals contains previously unsuspected light-sensitive cells,11 other than the familiar rods and cones. These comprise a small subclass of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs), the last relay station in the eye that sends information to the brain, and were dubbed intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs); ipRGCs mediate a host of non-visual light-dependent functions, such as photo-entraining circadian rhythms12 and controlling the pupillary reflex.13 The light-absorbing molecule that mediates the photoresponse of ipRGCs, melanopsin, turned out to be significantly more similar to the photopigments of invertebrate microvillar photoreceptors than those of vertebrates.14 Other molecular and developmental markers, such as expression of transcription factors BarH and Brn3, also suggest a kinship between ipRGCs and their invertebrate cousins.15 The detailed chemical cascade that couples light stimulation to the electrical response proved difficult to investigate in native cells, owing to their extreme scarcity, although clues are emerging that PLC is implicated.16,17 However, the characteristic microvillar morphology is conspicuously absent in ipRGCs, leaving considerable uncertainty about the presence and evolutionary history of microvillar receptors within the vertebrate phylum.

One possible strategy to search for the missing descendants of microvillar photoreceptors amongst deuterostomia is to focus on some early chordate, in which characteristic traits of the light-sensor may have been unambiguously retained. Amphioxus (Fig. 2A) is a primitive marine organism of great importance in evolutionary studies. Its genome has been recently sequenced18 and molecular phylogeny has established that it is the most basal of all living chordates;19 most important, it seemingly remains close to its ancestral condition, having changed little in the last half a million years. As such, it provides an unusually favorable window to examine biological mechanisms that may have been present in the ancestors of vertebrates. However, no functional study had been conducted on this species. Melanopsin was recently detected in the neural tube of amphioxus,20 its expression pattern coinciding with two previously described clusters of microvilli-bearing cells: Joseph cells and organs of Hesse.21–23 This observation set the stage for a recent study of single-cell physiology.24 Morphologically intact cells of both types were isolated (Fig. 2B and C), and electrophysiological recording was used to determine that they respond to light in the absence of all synaptic input (Fig. 3), thus establishing that they are indeed primary photoreceptors. The action spectrum matches that of melanopsin, peaking in the vicinity of 470 nm. Light mobilizes calcium from intracellular stores, as revealed by digital fluorescence imaging, and increases the permeability of the membrane to sodium and calcium ions, just like in microvillar receptors of insects and mollusks.25

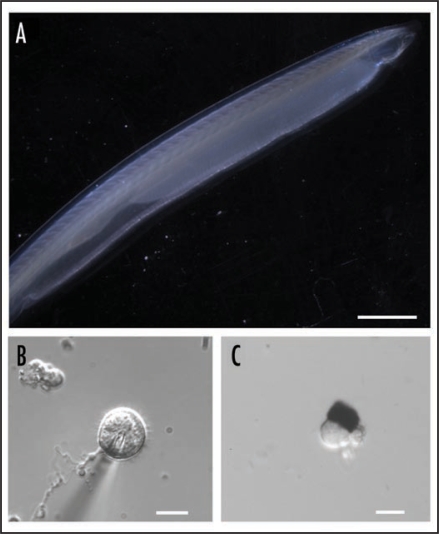

Figure 2.

The amphioxus (Branchiostoma floridae). (A) Intact specimen. Calibration bar: 5 mm (B) Joseph cell enzymatically dissociated from the neural tube (the shadow is a recording patch microelectrode). (C) Isolated organ of Hesse, comprised of a pigmented cell and a separate, microvilli-bearing translucent cell. Calibration bars in (B and C): 10 µm.

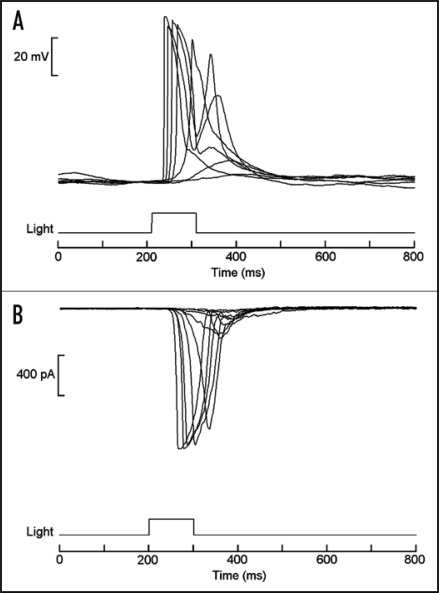

Figure 3.

Light responses in isolated organ of Hesse. (A) Superimposed traces of membrane voltage recording, showing depolarization elicited by brief flashes of light. (B) Light-activated inward currents measured under voltage clamp by the whole-cell patch recording technique. In both cases stimuli were delivered every minute, and the intensity of the light was increased at 0.6 log increments. Similar responses were also obtained from Joseph cells.

Additionally, key signaling molecules of the biochemical cascade that operates in invertebrate photoreceptors have been detected by western blot analysis, and the light response was shown to be susceptible to pharmacological agents that antagonize the PLC signaling pathway.26 The results firmly establish the presence of bona fide microvillar receptors among chordates, and confirm that melanopsin utilizes the same biochemical signaling mechanisms found in invertebrates; as such, amphioxus Hesse and Joseph cells can be viewed as bridging the gap between the melanopsin-expressing circadian receptors of mammals and their microvillar cousins in invertebrate eyes.

The scenario may be ripe to re-visit some basic questions related to the evolutionary origin of photoreceptors cells. Vision had previously been thought to have arisen independently several dozen times throughout animal evolution27—a reasonable proposition in view of the strong evolutionary pressure and the undeniable competitive advantage conferred by the ability to exploit the abundantly available electromagnetic radiation for information-gathering purposes. However, this conjecture became difficult to sustain with the realization that the early signaling elements of the light-transduction cascade in distant species are orthologous,15 even across the microvillar-ciliary boundary; this applies to the photopigment, the G-protein, and arrestin. In fact, examination of the transduction mechanisms in photoreceptors of bivalve marine mollusks28 and jellyfish29 indicates that the variety of light-signaling schemes amongst animals is actually richer than previously suspected, and yet in all cases a similar general blueprint is followed. The alternative, at the opposite end of the spectrum, is therefore a monophyletic origin, which naturally raises the question of which cell type may have been the ‘original’ photoreceptor. Spatial vision necessarily calls for directional sensitivity, and in its most primitive form it would entail a light sensor shielded on one side by a screen, as first envisioned by Darwin.30 Because in all known primordial pigmented ocelli microvillar photoreceptors are implicated, it has been argued that the ancestral proto-eye may have consisted of a single microvillar photoreceptor associated with a pigmented cell,31,32 i.e., exactly like the organ of Hesse of present-day amphioxus.

Footnotes

Previously published online as a Communicative & Integrative Biology E-publication: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cib/article/9244

References

- 1.Land MF, Nilsson D-E. Animal Eyes. Oxford U.K: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schneuwly S, Burg MG, Lending C, Perdew MH, Pak WL. Properties of photoreceptor-specific phospholipase C encoded by the norpA Gene of Drosophila melanogaster. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:24314–24319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fesenko EE, Kolesnikov SS, Lyubarsky AL. Induction by cyclic GMP of cationic conductance in plasma membrane of retinal rod outer segment. Nature. 1985;313:310–313. doi: 10.1038/313310a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gomez M, Nasi E. Activation of light-dependent potassium channels in ciliary invertebrate photoreceptors involves cGMP but not the IP3/Ca cascade. Neuron. 1995;15:607–618. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90149-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin VJ. Photoreceptors of cnidarians. Can J Zool. 2002;80:1703–1722. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saló E, Pineda D, Marsal M, Gonzalez J, Gremigni V, Batistoni R. Genetic network of the eye in Platyhelminthes: expression and functional analysis of some players during planarian regeneration. Gene. 2002;287:67–74. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00863-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorman ALF, McReynolds JS. Hyperpolarizing and depolarizing receptor potentials in the scallop eye. Science. 1969;165:309–310. doi: 10.1126/science.165.3890.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomez M, Nasi E. The light-sensitive conductance of hyperpolarizing invertebrate photoreceptors: a patch-clamp study. J Gen Physiol. 1994;103:939–956. doi: 10.1085/jgp.103.6.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arendt D, Tessmar-Raible K, Snyman H, Dorresteijn AW, Wittbrodt J. Ciliary photoreceptors with a vertebrate-type opsin in an invertebrate brain. Science. 2004;306:869–871. doi: 10.1126/science.1099955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Purschke G, Arendt D, Hausen H, Müller MCM. Photoreceptor cells and eyes in Annelida. Arthrop Struct Dev. 2006;35:211–230. doi: 10.1016/j.asd.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berson D, Dunn F, Takao M. Phototransduction by retinal ganglion cells that set the circadian clock. Science. 2002;295:1070–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.1067262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devlin PF, Kay SA. Circadian photoreception. Annu Rev Physiol. 2001;63:677–694. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kardon R. Pupillary light reflex. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 1995;6:20–26. doi: 10.1097/00055735-199512000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Provencio I, Jiang G, De Grip W, Hayes W, Rollag M. Melanopsin: an opsin in melanophores, brain and eye. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:340–345. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arendt D. Evolution of eyes and photoreceptor cell types. Int J Dev Biol. 2003;47:563–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sekaran S, Lall GS, Ralphs KL, Wolstenholme AJ, Lucas RJ, Foster RG, et al. 2-Aminoethoxydiphenylborane is an acute inhibitor of directly photosensitive retinal ganglion cell activity in vitro and in vivo. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3981–3986. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4716-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graham DM, Wong KY, Shapiro P, Frederick C, Pattabiraman K, Berson DM. Melanopsin ganglion cells use a membrane associated rhabdomeric phototransduction cascade. J Neurophysiol. 2008;99:2522–2532. doi: 10.1152/jn.01066.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Putnam NH, Butts T, Ferrier DE, Furlong RF, Hellsten U, Kawashima T, et al. The amphioxus genome and the evolution of chordate karyotype. Nature. 2008;453:1064–1072. doi: 10.1038/nature06967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schubert M, Escriva H, Neto J-X, Laudet V. Amphioxus and tunicates as evolutionary model systems. Trends Ecol Evol. 2006;21:269–277. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koyanagi M, Kubokawa K, Tsukamoto H, Shichida Y, Terakita A. Cephalochordate melanopsin: evolutionary linkage between invertebrate visual cells and vertebrate photosensitive retinal ganglion cells. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1065–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eakin RM, Westfall JA. Fine structure of photoreceptors in Amphioxus. J Ultra Res. 1962;6:531–539. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(62)80007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakao T. On the fine structure of the amphioxus photoreceptor. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1964;82:349–363. doi: 10.1620/tjem.82.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watanabe T, Yoshida M. Morphological and histochemical studies on Joseph cells of amphioxus, Branchiostoma belcheri Gray. Exp Biol. 1986;46:67–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gomez M, Angueyra JM, Nasi E. Light-transduction in melanopsin-expressing photoreceptors of amphioxus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:9081–9086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900708106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nasi E, Gomez M, Payne R. Phototransduction mechanisms in microvillar and ciliary photoreceptors of invertebrates. In: Hoff AJ, Stavenga DG, de Grip WJ, Pugh EN, editors. Molecular Mechanisms in Visual Transduction—Handbook of Biological Physics. Vol. 3. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 2000. pp. 389–448. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gomez M, Angueyra JM, Nasi E. Examining the ancient phototransduction mechanisms of a primitive chordate. J Gen Physiol. 2008;132:4. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salvini-Plawen LV, Mayr E. On the evolution of photoreceptors and eyes. Evol Biol. 1977;10:207–263. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomez M, Nasi E. Light transduction in invertebrate hyperpolarizing photoreceptors: involvement of a Go-regulated guanylate cyclase. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5254–5263. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-14-05254.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koyanagi M, Takano K, Tsukamoto H, Ohtsu K, Tokunaga F, Terakita A. Jellyfish vision starts with cAMP signaling mediated by opsin-Gs cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:15576–15580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806215105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Darwin C. On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection: or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. London: John Murray; 1859. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gehring WJ, Ikeo K. Pax 6: mastering eye morphogenesis and eye evolution. Trends Genet. 1999;15:371–377. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01776-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arendt D, Wittbrodt J. Reconstructing the eyes of urbilateria. Phil Trans Roy Soc Lond B. 2001;356:1545–1563. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.0971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]