Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the association between subfertility in men and the subsequent risk of testicular cancer.

Design

Population based case-control study.

Setting

The Danish population.

Participants

Cases were identified in the Danish Cancer Registry; controls were randomly selected from the Danish population with the computerised Danish Central Population Register. Men were interviewed by telephone; 514 men with cancer and 720 controls participated.

Outcome measure

Occurrence of testicular cancer.

Results

A reduced risk of testicular cancer was associated with paternity (relative risk 0.63; 95% confidence interval 0.47 to 0.85). In men who before the diagnosis of testicular cancer had a lower number of children than expected on the basis of their age, the relative risk was 1.98 (1.43 to 2.75). There was no corresponding protective effect associated with a higher number of children than expected. The associations were similar for seminoma and non-seminoma and were not influenced by adjustment for potential confounding factors.

Conclusion

These data are consistent with the hypothesis that male subfertility and testicular cancer share important aetiological factors.

Key messages

The incidence of testicular cancer has increased in the past 50 years, and there is some evidence to suggest that sperm quality has decreased in the same period

It has been hypothesised that common aetiological factors may exist for testicular cancer and for male subfertility

The association between male subfertility and subsequent risk of testicular cancer is strong and consistent with the hypothesis of a common aetiology

The association is similar for seminoma and non-seminoma, and it persists when several potentially confounding factors are taken into account

Introduction

The incidence of testicular cancer has been increasing in many populations over the past decades.1–3 Concerns have also been expressed about possible decreases in semen quality in the same period.4–9 During the past 20 years research into the causes of testicular cancer has pursued the hypothesis of prenatal aetiology.10–14 More recently it has been hypothesised that both testicular cancer and male subfertility may be caused by exposure of the developing male embryo to agents that disrupt normal hormonal balance.15 We explored the relation between male subfertility and testicular cancer using data from a population based case-control study in Denmark.

Methods

Cases of testicular cancer were identified in the Danish Cancer Registry, which holds information on all cases of cancer in the Danish population.16 We attempted to contact all men born in Denmark between 1916 and 1970 who were given a first diagnosis of testicular cancer in Denmark in the period 1986-8. Controls were identified from the Danish Central Population Register, a computerised database of the entire Danish population. The sampling frame consisted of all men born in Denmark between 1916 and 1970 who were alive at the time of study. Controls were frequency matched to the cases by year of birth to ensure comparability with respect to age. Men who had developed testicular cancer before 1986 were not considered eligible as controls.

The men were approached by mail, and participation in the study involved a telephone interview lasting 20-30 minutes. Interviews were conducted in 1989-90 by specially trained staff, and the interview comprised a list of short, concise questions about reproduction, sexual habits, cohabitation and marriage, education, selected diseases, and other relevant characteristics. All participants were questioned in a similar fashion, but it was not possible to blind the interviewers with respect to the case or control status of each participant.

There were 698 incident cases of testicular cancer in Denmark in the period 1986-8 in men born between 1916 and 1970. Of these, 584 men were approached and 514 (88%) participated. The reasons for not approaching 114 men were 52 were dead, 23 were born outside Denmark, three had emigrated, six had had testicular cancer before 1986, 19 were notified to the Danish Cancer Registry too late to be identified, and 11 were missed in the manual retrieval of notification forms in the cancer registry. According to the histology data collected routinely at the cancer registry the 514 cases included 262 men with seminoma, 239 with non-seminoma, and 13 with other or unspecified testicular cancers. Among 1049 men who were approached as controls 720 (69%) agreed to participate and were subsequently interviewed.

A date of diagnosis was available for the men with testicular cancer. Men in the control group were randomly assigned a “date of diagnosis” with a distribution equivalent to that of the cases. Time related characteristics were considered only for the period before the date of diagnosis and the corresponding point in time for the controls. The years of birth of all children of the men were obtained; in the analyses we considered only those children born 2 or more full calendar years before the year of diagnosis. Each man was assigned a relative fertility measure with the following method. In the control group the median number of children born 2 full years before the “year of diagnosis” was calculated separately for men in each birth cohort (1916-70). Then the fertility of each man in the study was classified as low, normal, or high, depending on whether the number of his children born 2 full years before the year of diagnosis was lower than, equal to, or higher than the corresponding median value (as an integer) in the control group.

Analysis

The data were analysed with unconditional logistic regression analysis.17 Controls were frequency matched to the cases by year of birth, and the stratification variable year of birth (in nine categories) was included in all analyses to ensure comparability of cases and controls with respect to age. The logistic regression analysis provides the odds ratio associated with a given risk factor or given level of categorical variable along with its 95% confidence interval. The odds ratios are estimates of the relative risk in individuals with a given characteristic compared with individuals without that characteristic. Statistical tests (two sided) for trend over several categories were carried out by assigning the values 1, 2, 3, etc, to successive categories and including the resulting variable in the regression analysis.

Results

Men who had fathered a child or who had impregnated a woman had a significantly decreased subsequent risk of testicular cancer (odds ratio 0.63 (95% confidence interval 0.47 to 0.83) for pregnancy and 0.63 (0.47 to 0.85) for paternity; table 1). The reduction in risk seemed to increase with each successive child. Men with low relative fertility had double the risk of testicular cancer (1.98; 1.43 to 2.75) compared with men with the expected number of children for their age. High relative fertility, however, carried no reduction in the risk of testicular cancer (1.22 (0.88 to 1.67) and 1.42 (1.01 to 1.98) in multivariate analysis).

Table 1.

Associations between fertility and subsequent risk of testicular cancer in Danish men

| Detail | No (%) | No (%) of | Odds ratio | Adjusted odds ratio* (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| of cases (n=514) | controls | (95% CI) | ||

| (n=720) | ||||

| Ever impregnated woman | 276 (54) | 486 (68) | 0.63 (0.47 to 0.83) | 0.65 (0.48 to 0.88) |

| Ever fathered child | 232 (45) | 427 (59) | 0.63 (0.47 to 0.85) | 0.68 (0.50 to 0.94) |

| No of children: | ||||

| 0 | 282 (55) | 293 (41) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | 75 (15) | 114 (16) | 0.69 (0.47 to 0.99) | 0.75 (0.51 to 1.10) |

| 2 | 117 (23) | 197 (27) | 0.65 (0.46 to 0.92) | 0.68 (0.47 to 0.98) |

| ⩾3 | 40 (8) | 116 (16) | 0.44 (0.28 to 0.71) | 0.52 (0.32 to 0.85) |

| Trend† | P<0.001 | P<0.01 | ||

| Relative fertility: | ||||

| Low | 145 (28) | 156 (22) | 1.98 (1.43 to 2.75) | 2.13 (1.51 to 3.00) |

| Normal | 260 (51) | 389 (54) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| High | 109 (21) | 175 (24) | 1.22 (0.88 to 1.67) | 1.42 (1.01 to 1.98) |

Adjusted for cryptorchidism, testicular atrophy, characteristics described in table 3, sex with prostitutes, and sexually transmitted diseases.

Test for linear trend in odds ratio over categories.

When we analysed the results separately we found them to be similar for the two main histological types of testicular cancer: seminoma and non-seminoma (table 2). In addition, when we adjusted the results for several potentially confounding factors by multivariate analysis the differences were small (table 1). The possible confounding effects of cryptorchidism or testicular atrophy (both of which are associated with testicular cancer and with subfertility) were further assessed by restricting the analysis to cases and controls without these characteristics; this analysis also produced results similar to those in table 1.

Table 2.

Associations between fertility and subsequent risk of testicular seminoma and non-seminoma in Danish men

| Detail | Seminoma

|

Non-seminoma

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (%) of cases (n=262) | No (%) of controls (n=720) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | No (%) of cases (n=239) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | ||

| Ever impregnated woman | 171 (65) | 486 (68) | 0.64 (0.45 to 0.91) | 98 (41) | 0.63 (0.43 to 0.91) | |

| Ever fathered child | 151 (58) | 427 (59) | 0.63 (0.44 to 0.90) | 75 (31) | 0.63 (0.42 to 0.96) | |

| No of children: | ||||||

| 0 | 111 (42) | 293 (41) | 1.00 | 164 (69) | 1.00 | |

| 1 | 43 (16) | 114 (16) | 0.68 (0.44 to 1.07) | 29 (12) | 0.66 (0.40 to 1.09) | |

| 2 | 76 (29) | 197 (27) | 0.66 (0.44 to 0.99) | 38 (16) | 0.67 (0.40 to 1.10) | |

| ⩾3 | 32 (12) | 116 (16) | 0.49 (0.29 to 0.83) | 8 (3) | 0.39 (0.16 to 0.91) | |

| Trend* | P<0.01 | P=0.02 | ||||

| Relative fertility: | ||||||

| Low | 94 (36) | 156 (22) | 2.11 (1.44 to 3.07) | 47 (20) | 1.70 (1.06 to 2.74) | |

| Normal | 101 (39) | 389 (54) | 1.00 | 154 (64) | 1.00 | |

| High | 67 (26) | 175 (24) | 1.33 (0.90 to 1.95) | 38 (16) | 0.98 (0.62 to 1.54) | |

Test for linear trend in odds ratio over categories.

Table 3 shows the analysis of selected reproductive characteristics. The only significant differences between men with and without testicular cancer were an older age at first sexual intercourse and a higher number of lifetime female sexual partners in the men with testicular cancer. Other characteristics that could indicate a difference in the desire or opportunity to have children were distributed equally in the two groups of men. Sex with prostitutes and sexually transmitted diseases were not associated with testicular cancer (data not shown).

Table 3.

Associations between selected reproductive characteristics and subsequent risk of testicular cancer in Danish men

| Detail | No (%) of cases (n=514) | No (%) of controls (n=720) | Adjusted odds ratio* |

|---|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) | |||

| Mumps orchitis | 34 (7) | 63 (9) | 0.65 (0.38 to 1.13) |

| Age at first intercourse: | |||

| <16 | 205 (40) | 268 (37) | 1.00 (0.75 to 1.32) |

| 17-19 | 211 (41) | 330 (46) | 1.00 |

| ⩾20 | 97 (19) | 120 (17) | 1.59 (1.10 to 2.30) |

| NA | 1 | 2 | |

| Trend† | P=0.08 | ||

| No of female sex partners: | |||

| 0-4 | 178 (35) | 265 (37) | 0.97 (0.72 to 1.32) |

| 5-19 | 173 (34) | 271 (38) | 1.00 |

| ⩾20 | 153 (30) | 171 (24) | 1.59 (1.15 to 2.21) |

| NA | 10 (2) | 13 (2) | |

| Trend† | P=0.02 | ||

| Ever lived with woman as partner, married or not | 413 (80) | 593 (82) | 1.00 (0.72 to 1.40) |

| Long duration of education | 122 (24) | 156 (22) | 1.01 (0.76 to 1.36) |

| Ever had sex with man | 15 (3) | 16 (2) | 1.57 (0.74 to 3.32) |

NA = not available.

Mutually adjusted and adjusted for cryptorchidism, testicular atrophy, sex with prostitutes, and sexually transmitted diseases.

Test for linear trend in odds ratio over categories.

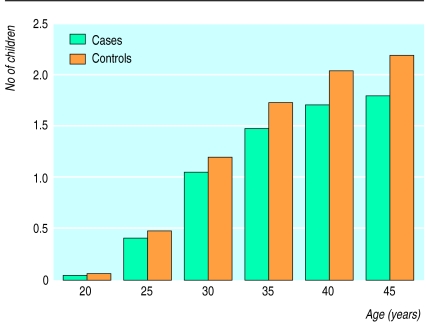

The figure shows the mean cumulative age specific fertilities of cases and controls, adjusted for year of birth (in three broad categories). The lower fertility in cases than in controls could be seen from an early age, and the difference gradually became larger over the reproductive lifetimes of these men. Towards the end of the reproductive years the difference in fertility amounted on average to about one half child. As in the preceding analyses we considered only those children born up to 2 full calendar years before the year of diagnosis; the observed difference is therefore not likely to be caused by the presence of overt clinical disease or its treatment.

Discussion

Our study, which used population based sampling of a large number of cases of testicular cancer and control participants, shows a strong significant association between male subfertility and the subsequent risk of testicular cancer. Considered as a group, men who have a lower number of children than is usual for their age have about twice the risk of developing testicular cancer when compared with other men.

Study validity

Relative fertility is an imperfect measure of subfertility; some men with normal reproductive potential will be classified as having low relative fertility merely because they have had no or few children for reasons unrelated to their ability to father children. The consequence of such random misclassification (which is inevitable in the absence of semen tests and other direct measurements) is to reduce the magnitude of the observed association.18 Therefore, the true association between subfertility and testicular cancer is likely to be even stronger than suggested by the estimated relative risks.

The critical information collected for our analysis is simple. When men with and without testicular cancer are asked to provide information regarding the number of children they have fathered and the years in which the children were born answers to these questions imply a minimum of interpretation (in contrast with questions about infertility, difficulty in conceiving, or waiting time to pregnancy). Thus, the potential for information bias because of differential recall or interpretation in the present study is minimal. Nevertheless, self reported numbers of children fathered by a man is not a perfect measure. Some men may report children who in reality are not their own biological offspring, either to avoid the issues of donor insemination or adoption or because they do not know. The effect of this misclassification, however, would be to diminish the differences between cases and controls and not to create them.

Interpretation

While low relative fertility is associated with testicular cancer, there is no corresponding protective effect in men with high relative fertility, which on the contrary had borderline significant association with increased risk of testicular cancer in the multivariate analysis (table 1). This shows that the association with low relative fertility is not due to the actual fact of having a child, as is, for example, the case for breast cancer in women.19 Our data rather suggest that the risk of testicular cancer is associated with the constitutional characteristic of being infertile or subfertile. This interpretation is further supported by the insensitivity of the estimated parameters to statistical adjustment for potentially confounding factors and by the similar distributions in cases and controls of characteristics potentially associated with low fertility (for example, mumps orchitis, long duration of education, homosexuality) and other relevant sexual characteristics (for example, cohabitation with a woman, sex with female prostitutes, sexually transmitted diseases). The case and control participants in this study were generally similar with respect to socioeconomic characteristics.20 The elimination from the analysis of the 2 full calendar years before the diagnosis of testicular cancer (and the corresponding period of time for controls) ensured that the association between subfertility and testicular cancer was not simply due to the effect of clinical disease on reproductive behaviour. The most plausible explanation for the observed association between subfertility and testicular cancer is that common factors exist which increase the risk of both subfertility and testicular cancer. Several other lines of evidence support this explanation.

The observation of a strong cohort effect in the time trend of testicular cancer and the observation of a marked reduction in incidence of testicular cancer throughout life in men born in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden during the second world war compared with men born just before or just after the war, lends support to this idea.12,21 Additional evidence comes from analytical epidemiological studies of testicular cancer, which have shown consistent associations with low birth weight14,22 and with congenital malformations of the male sexual organs.13,23

In patients with testicular cancer who are treated by surgery alone low sperm counts and high values of follicle stimulating hormone were observed at the time of orchidectomy and during the following years.24,25 In addition, studies of testicular tissue from such patients have shown that abnormal morphology and impaired spermatogenesis are common features, both in the testicle with cancer26 and in the contralateral testicle.24 This probably reflects a condition of permanently impaired reproductive capacity that precedes and is not caused by the presence of a tumour in the other testicle.

Conclusion

We found that testicular cancer occurs more commonly in men who have fathered no or only few children when the age of the man is taken into account. In conjunction with studies of testicular histology and function these data support the hypothesis that male subfertility is associated with a high risk of testicular cancer. The most plausible explanation for this association is the existence of causal factors that are common to both subfertility and testicular cancer. The epidemiology and biology of testicular cancer suggest that such common causes may act prenatally.

Figure.

Mean cumulative age specific fertilities of men with testicular cancer and of control men

Acknowledgments

Lars Grønbjerg assisted with the data analysis.

Footnotes

Funding: Danish Cancer Society and the Danish Medical Research Council.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Coleman MP, Esteve J, Damiecki P, Arslan A, Renard H. Trends in cancer incidence and mortality. IARC Sci Publ. 1993;121:521–542. doi: 10.3109/9780415874984-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forman D, Møller H. Trends in incidence and mortality of testicular cancer. Cancer Surveys. 1994;19/20:323–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adami HO, Bergstrom R, Mohner M, Zatonsky W, Storm H, Ekbom A, et al. Testicular cancer in nine northern European countries. Int J Cancer. 1994;59:33–38. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910590108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bostofte E, Serup J, Rebbe H. Has the fertility of Danish men declined through the years in terms of semen quality? A comparison of semen qualities between 1952 and 1972. Int J Fertil. 1983;28:91–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bendvold E. Semen quality in Norwegian men over a 20-year period. Int J Fertil. 1989;34:401–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlsen E, Giwercman A, Keiding N, Skakkebæk NE. Evidence for decreasing quality of semen during past 50 years. BMJ. 1992;305:609–613. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6854.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Auger J, Kunstmann JM, Czyglik F, Jouannet P. Decline in semen quality among fertile men in Paris during the past 20 years. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:281–285. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199502023320501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irvine S, Cawood E, Richardson D, MacDonald E, Aitken J. Evidence of deteriorating semen quality in the United Kingdom: birth cohort study in 577 men in Scotland over 11 years. BMJ. 1996;312:467–471. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7029.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pajarinen J, Laippala P, Penttila A, Karhunen PJ. Incidence of disorders of spermatogenesis in middle aged Finnish men, 1981-91: two necropsy series. BMJ. 1997;314:13–18. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7073.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henderson BE, Benton B, Jing J, Yu MC, Pike MC. Risk factors for cancer of the testis in young men. Int J Cancer. 1979;23:598–602. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910230503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skakkebæk NE, Berthelsen JG, Giwercman A, Müller J. Carcinoma-in-situ of the testis: possible origin from gonocytes and precursor of all types of germ cell tumours except spermatocytoma. Int J Androl. 1987;10:19–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.1987.tb00161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Møller H. Clues to the aetiology of testicular germ cell tumours from descriptive epidemiology. Eur Urol. 1993;23:8–13. doi: 10.1159/000474564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.United Kingdom Testicular Cancer Study Group. Aetiology of testicular cancer: association with congenital abnormalities, age at puberty, infertility, and exercise. BMJ. 1994;308:1393–1399. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Møller H, Skakkebæk NE. Testicular cancer and cryptorchidism in relation to prenatal factors: case-control studies in Denmark. Cancer Causes Control. 1997;8:904–912. doi: 10.1023/a:1018472530653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharpe RM, Skakkebæk NE. Are oestrogens involved in falling sperm counts and disorders of the male reproductive tract? Lancet. 1993;341:1392–1395. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90953-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Storm HH. The Danish cancer registry: a self-reporting national cancer registration system with elements of active data collection. IARC Sci Publ. 1991;95:220–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breslow NE, Day NE. Statistical methods in cancer research. Vol I. The analysis of case-control studies. IARC Sci Publ. 1980;32:5–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Armstrong BK, White E, Saracci R. Principles of exposure measurement in epidemiology. Monographs in epidemiology and biostatistics. Vol. 21. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacMahon B, Cole P, Lin TM, Lowe CR, Mirra AP, Ravnihar B, et al. Age at first birth and cancer of the breast. A summary of an international study. Bull World Health Organ. 1970;43:209–221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Møller H, Skakkebæk NE. Risks of testicular cancer and cryptorchidism in relation to socio-economic status and related factors: case-control studies in Denmark. Int J Cancer. 1996;66:287–293. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960503)66:3<287::AID-IJC2>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bergstrom R, Adami HO, Mohner M, Zatonski W, Storm H, Tretli S, et al. Increase in testicular cancer in six European countries: a birth cohort phenomenon. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:727–733. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.11.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akre O, Ekbom A, Hsieh CC, Trichopoulos D, Adami HO. Testicular nonseminoma and seminoma in relation to perinatal characteristics. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:883–889. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.13.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Møller H, Prener A, Skakkebæk NE. Testicular cancer, cryptorchidism, inguinal hernia, testicular atrophy, and genital malformations: case-control studies in Denmark. Cancer Causes Control. 1995;7:264–274. doi: 10.1007/BF00051302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berthelsen JG, Skakkebæk NE. Gonadal function in men with testis cancer. Fertil Steril. 1983;39:68–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hansen PV, Trykker H, Helkjær PE, Andersen J. Testicular function in patients with testicular cancer treated with orchiectomy alone or orchiectomy plus cisplatin-based chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81:1246–1250. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.16.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ho GT, Gardner H, DeWolf WC, Loughlin KR, Morgentaler A. Influence of testicular carcinoma on ipsilateral spermatogenesis. J Urol. 1992;148:821–825. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36732-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]