Abstract

We conducted phylogenetically informed comparative analyses of 81 taxa of Dalechampia (Euphorbiaceae) vines and shrubs to assess the roles of historical contingency and trait interaction in the evolution of plant-defense and pollinator-attraction systems. We asked whether defenses can originate by exaptation from preexisting pollinator attractants, or vice versa, whether plant defenses show escalation, and if so, whether by enhancing one line of defense or by adding new lines of defense. Two major patterns emerged: (i) correlated evolution of several complementary lines of defense of flowers, seeds, and leaves, and (ii) 5 to 6 losses of the resin reward, followed by redeployment of resin for defense of male flowers in 3 to 4 lineages, apparently in response to herbivore-mediated selection for defense of staminate flowers upon relaxation of pollinator-mediated selection on resin. In all cases, redeployment of resin involved reversion to the inferred ancestral arrangement of flowers and resiniferous bractlets. Triterpene resin has also been deployed for defense of leaves and developing seeds. Other unique defenses against florivores include nocturnal closure of large involucral bracts around receptive flowers and permanent closure around developing fruits (until opening again upon dehiscence). Escalation in one major clade occurred through an early dramatic increase in the number of lines of defense and in the other major clade by more limited increases throughout the group's evolution. We conclude that preaptations played important roles in the evolution of unique defense and attraction systems, and that the evolution of interactions with herbivores can be influenced by adaptations for pollination, and vice versa.

Keywords: floral resin, florivory, plant defense, resin defense

It is accepted that most plant species experience a variety of antagonistic and mutualistic relationships with animals simultaneously or sequentially over the course of their lives. To date, however, most research has focused on only 1 type of interaction at a time (e.g., herbivory ignoring pollination or pollination ignoring herbivory) (1). Less frequently considered are the interactions between these partnerships (e.g., how pollination and herbivory might interact evolutionarily).

Interactive effects of herbivory and pollination on plant reproductive success have been detected in a number of microevolutionary studies; these reveal surprisingly strong effects and complex, sometime counterintuitive, responses (2, 3). For example, the evolution of flowers may be influenced by selection generated as much by nonpollinating agents as by pollinators (4–6; but see ref. 7), in contrast to traditional expectations that pollinators alone drive floral evolution (8). Research on interactions between various plant–animal relationships has naturally focused on ecology (e.g., the immediate growth and/or reproductive outcomes of complex interactions). Although an evolutionary perspective underlies these studies, few studies have explicitly considered the long-term evolutionary dynamics of plant interactions with multiple partners (but see articles cited below).

One advantage of taking a long-term approach to evolutionary analysis is that it sometimes permits detection of the causes of evolutionary novelty, such as invasion of new adaptive zones (9) or escape from enemies through novel defenses, which can lead to subsequent evolutionary radiation (10, 11). An explicitly historical approach also allows evaluation of the role of historical contingency in evolutionary change (12)—for example, phylogenetic lag, genetic constraint, and preaptations (13–15). Phylogeny-based approaches allow tests of associations between traits or partnerships (16, 17) and whether particular traits or relationships influence the evolution of others (18).

Historical contingency is implicit in Ehrlich and Raven's escape-and-radiate hypothesis of plant–herbivore coevolution (10) and defensive escalation (11). Other historically contingent evolutionary scenarios include consistent sequences of trait change (“ordered change”) (18); exaptation (13) (e.g., coopting preexisting compounds for new defense or reward functions); and evolutionary “novelty” through regulatory gene–based trait reversals (“atavisms”) (19–21). Previous macroevolutionary studies of plant–herbivore interactions have shown patterns of escalation and decline in the intensity and effectiveness of different defense systems (22–24) and specific sequences of evolutionary change in plant defense systems (25, 26).

Macroevolutionary studies of the interactions between plant defense and attraction systems are few, although the importance of this link has long been recognized. In considering pollination of primitive angiosperms, Pellmyr and Thien (27) hypothesized that the secretion of essential oils by flowers originated as defense in response to selection generated by herbivores and/or pathogens. These mostly toxic compounds now play roles in advertisement and attract pollinators. The origin of floral advertisements by exaptation [sensu Gould and Vrba (13) and Arnold (28)] has been invoked as a key innovation in angiosperm evolution (27). It seems likely that many of these compounds today play dual roles in attraction and defense [see also Lev-Yadun (29)], that is, are “addition exaptations,” whereby a new function is added to, rather than replaces, the prior function (13, 28). Later studies based on phylogenetic approaches have also suggested that protection or defense functions often precede the attractive functions of biosynthetic products (4, 7, 30). For example, previous work suggested that the resin-reward system seen in Dalechampia vines and shrubs (Euphorbiaceae) and Clusia trees (Clusiaceae) evolved by exaptation, whereby resin secretion originated for defense and secondarily took on an attractive function (31). Armbruster et al. (32) provided some experimental support for this hypothesis. Working in the same system, Armbruster (33) also hypothesized that some antiherbivore defenses in Dalechampia vines and shrubs had their origins in pollinator attraction, although these conclusions were restricted to neotropical species and based on a morphologic phylogeny slightly at odds with our current knowledge (cf. 34).

Here we use new molecular–phylogenetic, morphologic, and chemical data from a worldwide sample of 81 neo- and paleotropical taxa of Dalechampia (Euphorbiaceae) to address the following questions: (i) Have some defense systems originated by exaptation from pollinator attractants, and some attractants originated from defense? (ii) Has selection for greater defense led to broad-sense escalation (22–24); if so, has this been through refinement of single lines of defense or, instead, by addition of new lines of defense? More specifically, we ask: (iii) Have new floral defense systems evolved subsequent to resin being redeployed as a pollinator reward rather than floral defense (transfer exaptation; 28, 33)? (iv) What happens when resin ceases to be a reward; is resin ever used again in floral defense; if so, how does this come about? (v) Have floral attraction and defense systems influenced the evolution of foliar defense systems?

Dalechampia comprises ≈120 species of monoecious twining vines and (rarely) shrubs, occurring throughout most of the neo- and paleotropics, west of Wallace's Line. Unisexual flowers are secondarily united into functionally bisexual, blossom inflorescences, usually subtended by 2 large, showy involucral bracts (Fig. 1), and are pollinated mostly by resin-collecting megachilid (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) or euglossine (Apidae) bees (35). Approximately 10 species in the neotropics are pollinated by fragrance-collecting male euglossine bees (35), and approximately 10 species in Madagascar and 2 in the neotropics are pollinated by pollen-feeding beetles and/or pollen-collecting bees (34). The foliage of neotropical species is fed upon by the larvae of specialist nymphalid butterflies (primarily Hamadryas and Ectima but also Catonephele, Myscelia, Mestra, and Biblis; ref. 36), as well as generalists, such as leaf-cutting ants, Atta (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Foliage of paleotropical species is eaten by the larvae of Byblia (Nymphalidae). Floral parts are fed upon by specialist butterfly larvae, Dynamine spp. in the neotropics and Neptidopsis in the paleotropics, as well as generalists, such as tettigoniid grasshoppers/katydids (Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae), especially at night (36). Rewards produced for pollinators include pollen (34), oxygenated triterpenes secreted by a condensed resin gland associated with the staminate subinflorescence (31, 32), and monoterpene fragrances secreted by either the stigmatic surface of the pistillate flowers (37) or a gland homologous with the resin gland (38, 39).

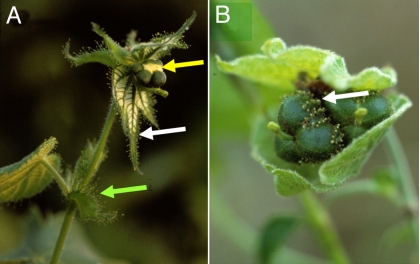

Fig. 1.

Blossom inflorescences (pseudanthia) in flower and fruit. (A) Receptive pseudanthium of D. stipulacea, a species that is pollinated by resin-collecting euglossine bees. Pseudanthia have resin glands (yellow arrow) formed by asymmetrical clusters of resiniferous staminate bractlets. The floral resin gland secretes a mixture of oxygenated triterpene ketones and alcohols (32). This species and its relatives also secrete the same oxygenated triterpene alcohols from capitate glands along the margins of stipules (green arrow), leaves, and involucral bracts (white arrow). (B) Capsular fruits of D. scandens, showing capitate glands (white arrow) on pistillate sepals, which secrete oxygenated-triterpene resin. Note also the involucral bracts, which are partially closed around the fruit. As the fruits mature these bracts begin to open (as here) in preparation for explosive dispersal of the seeds.

Results

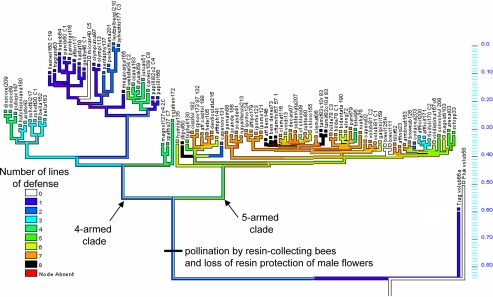

Bayesian posterior probabilities and maximum-parsimony bootstrap values from phylogenetic analyses of chloroplast DNA (cpDNA), internal transcribed spacer (ITS), and external transcribed spacer (ETS) sequence data provided strong support for numerous species groups and 2 major clades: species with 4 branches in the male subinflorescence (“4-armed clade”) and species with 5 branches (“5-armed clade”; Fig. 2 and supporting information Fig. S1). Maximum-likelihood optimization of traits onto the ultrametric Bayesian trees resampled from 22,500 retained ITS trees of the posterior distribution indicated 1 to 2 origins of stinging crystalliferous trichomes on vegetative parts (depending on whether Tragia and Dalechampia share this trait by common descent; see Fig. 2, first line of defense). Optimization also indicated that secretion of triterpene resin by floral structures originated once, sometime after the divergence of Dalechampia from Tragia. We cannot ascertain whether resin played an initial role in defense of staminate flowers or in rewarding pollinators, although the former seems more reasonable. Resin “immediately” took on the latter function (i.e., no descendants of the inferred basal state exist), however, and this function persists throughout most of the genus today. One line of defense based on a resin chemically similar to the reward originated early in the evolution of Dalechampia (but after the shift from resin defense of flowers to resin reward for pollinators): deployment of resin by sepals in defense of developing fruits [2 to 3 origins inferred from maximum-likelihood (ML) optimization; Table 1]. A second use of the same resin evolved much later: deployment of resin by stipules, leaves, and involucral bracts (one origin: Dalechampia stipulacea and relatives). In one lineage, secretion of resin from pistillate sepals is augmented by deployment of barbed, detaching, “glochidial” spines on the pistillate sepals. Although the order of trait gain cannot be detected [Discrete Ordered-Change test, likelihood ratio (LR) = 0.65 ± 0.07, P > 0.5; Table S1], resin glands and glochidia on the sepals show strong evidence of correlated evolution (Discrete Omnibus test, LR = 19.62 ± 0.15, P < 0.001; Table S1). Deployment of defensive spines and resin glands on pistillate sepals (Fig. 1B) evolved in concert with sepal size (LR = 19.62 ± 0.15, P < 0.001 and LR = 8.29 ± 0.08, P = 0.08, respectively; Table S1), usually originating after the sepals were large enough to envelop the ovaries and developing fruits (but LR = 0.65 ± 0.07, P > 0.50 in ordered-change test; Table S1). The combination of inflated bracts enclosing a mass of sharp, barbed, detachable spines seems to be a particularly effective defense combination (at least against humans), protecting developing seeds and fruits (presumably against granivorous mammals and birds, rather than botanists), and there is evidence of correlated evolution of these 2 traits (LR = 13.82 ± 1.21, P < 0.01; Table S1).

Fig. 2.

Escalatory and deescalatory evolution of lines of defense in Dalechampia, treating defense as a single ordinal trait (number of lines of defense). The tree is a typical representative of the 30,000 post–burn-in, nonultrametric Bayesian trees estimated from analysis of ITS sequence data, with branch lengths proportional to ITS divergence. The number of lines of defense was optimized across 100 trees sampled regularly from the posterior distribution, using MPRs (proportional most-parsimonious reconstruction tracing), ordered-trait evolution, and the map-across-all-trees options in Mesquite (63). The cross-sectional proportion of colors on a branch indicates the joint proportion of trees and maximally parsimonious reconstructions with that ancestor state at the node. The width of the red shading indicates the proportion of trees lacking that node. Scale on right indicates branch length.

Table 1.

Novel defense and attraction systems in Dalechampia (/Tragia), with inferred modes of origin

| Defense/pollination trait | Current function | Type of novelty | Source/process | Basis of inference for function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diffusely deployed resiniferous bractlets enveloping staminate flowers | Defense of male flowers and pollen from florivores | (i) Adaptation (inferred in ancestor); (ii) exaptation due to preexisting bractlets attracting pollinators and genetic information in extant spp for distributed arrangement (atavistic reversal) | In (ii), regulatory gene change leading to reexpression of ″suppressed″ genetic information (atavistic reversal)? | Experimental data (32) |

| Stinging crystalliferous trichomes that inject histamines | Defense of leaves from mammals? (and some insects?) | De novo adaptation | Unknown | Effect on humans |

| Nocturnal closure of involucral bracts | Protection of flower and pollen (from nocturnal insect herbivores) | Addition exaptation | Secondary adaptive modification of large, showy bracts | Experimental data (36) |

| Closed bracts in bud | Protection of flower buds (from insects) | Addition exaptation | Secondary adaptive modification of large, showy bracts | Extrapolation from Armbruster and Mziray (36) |

| Closed bracts in fruit | Protection of developing seeds and fruits (from insects) | Addition exaptation | Secondary adaptive modification of large, showy bracts | Unpublished experimental data |

| Resin secretion by pistillate sepals | Protection of ovules and developing seeds (from insects) | Addition exaptation | Expression of preexisting resin biosynthetic system in new tissues | Experimental data (32) |

| Detaching glochidial spines on pistillate sepals | Protection of seeds before dispersal (primarily from birds and mammals?) | De novo adaptation | Unknown | Effect on humans |

| Resin secretion by stipules, leaves, and bracts | Protection of vegetative parts (from Atta ants and other herbivores) | Addition exaptation | Expression of preexisting resin biosynthetic system in new tissues | Experimental data (32) |

| Resin reward | Attraction and reward of pollinating bees | Transfer exaptation | Exaptation from resin defense(?) | Comparison with outgroup, studies of other plant groups, field observations |

| Showy involucral bracts | Advertisement to pollinating bees | Adaptation or transfer exaptation (defined broadly) | Adaptive modification of leaves | Experimental data (40) |

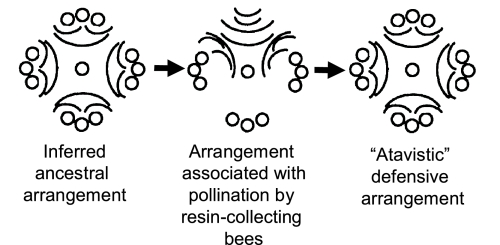

In 3 of 5 lineages, loss of the resin-reward function, related to shifts to pollination by fragrance- or pollen-collecting insects, was closely associated with redeployment of the resiniferous staminate bractlets in a fashion that promotes defense of the staminate flowers (Fig. 3 and Fig. S2). The evidence for correlated evolution of reward function (loss of resin-bee pollination), and bractlet/flower arrangement (defensive redeployment) was highly significant (LR = 21.04 ± 1.16, P < 0.001), although there was no evidence for one trait changing before, or influencing evolution of the other (Table S1). In the 2 lineages that do not conform to this pattern (D. brownsbergensis and D. spathulata-D. magnoliifolia), the staminate bractlets do not secrete resin and instead are vestigial or secrete monoterpene fragrance, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Repeated reorganization of staminate flowers and resiniferous bractlets in the male subinflorescence (cymule) of Dalechampia (4-armed clade depicted), associated with (i) the inferred shift from defense of male flowers with resin to attraction of pollinators with resin (left arrow), and (ii) the shift from pollination by resin-collecting bees to pollination by other kinds of insects and redeployment of bractlets in a defensive arrangement (right arrow). The redeployment of flowers in the putative ancestral arrangement argues for the role of regulatory-gene changes in both transitions. Circles represent staminate flowers and curved lines the resiniferous bractlets. The orientation of the diagram is the same as the orientation of the inflorescence in nature (i.e., the top of the diagram is the top the inflorescence) (Fig. 1).

Another line of defense of flowers and seeds involves nocturnal closure of enveloping bracts; this originated after the origin of large, showy bracts adjacent to the flowers (Fig. 1A). In one lineage (the 5-armed clade; Fig. 2, right branch) nocturnal closure originated early in the lineage's diversification, with virtually all extant species exhibiting this feature. In the 4-armed clade (Fig. 2, left branch), nocturnal closure originated several times rather late, such that approximately half the extant species have large bracts that do not close at night.

Examination of the sequence of changes in all defensive traits across the phylogeny of Dalechampia reveals a general pattern of early escalation in defensive systems in the 5-armed clade (1 line of defense increasing to approximately 7), followed by a number of minor reversals (deescalation: 7 lines of defense decreasing to 6 or 5; Fig. 2). In the 4-armed clade, in contrast, escalation is much more limited, with apparently less deescalation (Fig. 2). Analysis of the number of lines of defense with BayesTraits-Continuous revealed a strong phylogenetic signal in the evolution of defense systems and a tendency for defensive traits to evolve more slowly on long branches than on short branches and to show early radiation rather than later species-specific adaptation (Table 2). Over most of the evolutionary history of the group, defense systems have accumulated, being added more rapidly than lost (Fig. 2). Due to the repeated, small-scale reversals in the overall trend, however, the Continuous test for general evolutionary trends (escalation, in this case) was not significant (Table 2).

Table 2.

Evolutionary analysis of the number of lines of defense seen in Dalechampia species, using BayesTraits-Continuous (57–59), showing model parameters, likelihood ratios, and interpretations of results

| Parameter | Mean ML estimate (± SE) | Mean likelihood ratio (± SE) | P (mean) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| λ | 1.003 ± 0.004 | 85.94 ± 2.55 (against λ = 0) | <0.001 | Strong phylogenetic signal in data; trait variance explained significantly by tree topology |

| α | 2.834 ± 0.586 | — | ||

| β | −2.801 ± 0.579 | — | ||

| κ | 0.317 ± 0.024 | 5.608 ± 0.586 (against κ = 0) | <0.05 | Stasis on longer branches, some punctuated divergence |

| δ | 0.300 ± 0.019 | 4.838 ± 0.411 (against δ = 1) | <0.05 | Early adaptation important (adaptive radiation), evolution of defense is not purely gradualistic |

| Evolutionary trend, gradual model | 0.329 ± 0.055 (against model A) | NS | No detected overall directional trend for increase in number of lines of defense | |

| Evolutionary trend, speciation model | 1.359 ± 0.105 (against model A) | NS | No detected overall directional trend for increase in lines of defense |

Results are reported as the mean ± SE seen across 100 Bayesian trees regularly resampled from approximately 40,000 Bayesian trees retained from the posterior distribution. Branch lengths used were based on ITS data and were not constrained to ultrametric, following program restrictions (57). α is the estimated root value, and β is the directional change parameter, measuring the overall trait change against total path length from the root, in model B. Because model B was not significantly better than model A under either gradual- or speciation-change assumption, these two statistical parameters probably have no biologic meaning.

Species of Dalechampia show a distinctly nonnormal distribution with respect to the number of lines of defense: species tend to cluster at the upper or (secondarily) lower end of the distribution (Fig. S3). There thus seem to be 2 syndromes: (i) highly defended species, which are also largely “pioneer” species of secondary scrub (35), and (ii) poorly defended species, which are largely late-succession species of forests. Members of these 2 syndromes are, however, largely associated with different clades. Highly defended species all belong to the 5-armed clade (right branch, Fig. 2), and most poorly defended species belong to the 4-armed clade (left branch, Fig. 2). Thus, the apparent association between habitat and defense may reflect shared phylogenetic history instead of convergence. Nevertheless, phylogenetically controlled analysis with BayesTraits-Continuous showed a significant (although weak) association between defense and habitat (R2 = 0.05, LR = 5.37 ± 0.48, P < 0.05).

To assess whether innovations in defense or pollination had effects on rates of speciation, extinction, or net diversification, we estimated these parameters with BiSSE (see Materials and Methods). We could not, however, detect heterogeneity in speciation, extinction, or net diversification rates associated with any of the various innovations and changes in defense and pollination characters.

Five of seven evolutionary innovations in defense seem to have been the result of exaptation (origin of a trait by a change in function of a preexisting trait; Table 1). Changes to new functions were followed by further adaptive “fine tuning.” Initial functions were usually related to attracting pollinators. One innovation in pollination probably drew on a preexisting defense feature: secretion of resin in blossoms (Table 1).

Discussion

The evolutionary histories of plant-defense and pollinator-attraction systems in Dalechampia of both the neo- and paleotropics have been intertwined, linked by the mechanical and chemical commonalities of plant–animal interactions. There are repeated examples of features originating apparently in response to selection generated by one function (pollination or defense) and later being coopted for the other, often several times independently. This underscores the historical contingency of the evolution of plant–animal interactions and the importance of physical and chemical links between plants and insects.

The most puzzling feature of Dalechampia evolution revealed by the molecular phylogeny is repeated reversal in full detail to the inferred ancestral arrangement of the staminate flowers and resiniferous bractlets (Fig. 3 and Fig. S2). This may be explained by strong selection for protection of pollen (genomic copies) against florivores. The inferred ancestral arrangement of staminate flowers and bractlets (based on comparisons with candidate outgroups) was diffuse deployment of bractlets around the staminate flowers arranged in 4 to 5 fertile branches (Fig. 3). In this arrangement, male floral buds were protected by a layer of resin. After resin became a reward for pollinators, the resin-secreting bractlets became rearranged into a gland-like structure. The staminate flowers were then located below the gland, near the pistillate flowers, creating bilateral symmetry, enhancing the consistent positioning of the pollinators and thus floral precision and accuracy (Fig. 3; refs. 40–42). However, this resulted in resin no longer protecting the staminate flowers from pollen-feeding insects (= “transfer exaptation,” Table 1; refs. 28, 33). Resin was later replaced by pollen or fragrance as the pollinator reward 5 to 6 times; in 3 to 4 of these, the resiniferous bractlets were “immediately” (intermediates not extant) redeployed in the diffuse fashion that protects the staminate flowers. These reversals suggest that florivores that consume male gametes generate strong selection and that the easiest line of evolutionary response was to reactivate preexisting developmental information for the arrangement of the bractlets, information that was still in the genome but suppressed by regulatory genes. Support for this hypothesis derives from the fact that these apparent atavisms have occurred in identical detail independently 3 to 4 times on both deep and shallow branches in both South America and Madagascar. Additionally, the reversal includes rearrangement of the male flowers to the inferred ancestral decussate position, even though there is no obvious adaptive reason for this to occur.

The 2 exceptions to this trend can be explained by the fact that the bractlets lost their ability to secrete resin in the process of adapting to new pollinators, and as such were not influenced by selection for greater protection of the staminate flowers. In the lineage containing D. spathulata, the bractlets instead secrete monoterpene fragrances and remain asymmetrically clustered, orienting the pollinating bees as does the resin gland (38, 39). Hence, these species have not been “released” from pollinator-mediated selection against diffuse deployment. In the other exceptional lineage (D. brownsbergensis), the resin gland is vestigial and nonsecretory (37).

Defensive escalation in Dalechampia has occurred through increases in the number of lines of defense rather than refinement of a single line. The 4-armed clade exhibits a pattern of limited late escalation with few reversals. In contrast, the 5-armed clade exhibits dramatic early escalation followed by numerous minor losses or gains of defense systems much later (Fig. 2). One small clade, D. stipulacea and relatives, exhibits all but 1 line of defense “invented” by Dalechampia over its entire evolutionary history, illustrating the tendency for additive accumulation rather than substitution of lines of defense.

Anther difference between the 4-armed and 5-armed clades is that the latter species generally have higher levels of defense (Fig. 2) and tend to occupy secondary habitats. This would seem at first to contradict classic ideas (e.g., ref. 43) about fugitive species being less defended. However, it is possible that the leaves of late-succession species in the 4-armed clade are defended by structural carbohydrates and tannins or other phenolics (not measured), and a survey of these compounds in the future would be valuable.

In conclusion, a broad overview of this group's evolutionary history yields evidence of historically contingent evolution, including exaptation and the recurrence of developmental atavisms. It also suggests that exaptation and atavisms have played important roles in morphologic and chemical evolution of both defense and attraction systems.

Materials and Methods

Phylogenetic Analysis.

A molecular tree based on concatenated cpDNA (3′ trnK introns/partial matK) and 18S–26S nuclear ribosomal ETS and ITS sequences was generated from single individuals of 81 taxa (88 populations) of Dalechampia and 2 closely related outgroup species in Plukenetia and Tragia using Bayesian inference (Table S2). Although taxon sampling involved less than 70% of the species, those sampled represented all major subgeneric groups and all geographic regions in the global distribution, and captured critical diversity in pollinator reward, blossom morphology, and defense within Dalechampia (30–42, 44, 45). We expect that the effects of incomplete sampling are minimal, perhaps resulting in lower power but not bias or type 1 error. DNA extractions, PCR, and sequencing followed standard procedures (46–49), with design of an internal primer for ETS amplification and sequencing (5′-caa ctg ctc tta ggg gtt gct gtt-3′). Sequences were aligned in SeaView 4.0 (50) using MUSCLE (51) and adjusted manually. Four independent Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) analyses were conducted using MrBayes 3.1 (52), each using 3 “heated” and 1 “cold” chain(s) and 3 data partitions (for ITS, ETS, and cpDNA sequences). Best-fit evolutionary models for Bayesian phylogenetic analysis based on the Akaike information criterion in MrModeltest 2.3 (53) were GTR+I+Γ for the ITS region; HKY+Γ for the ETS, and GTR+G for cpDNA sequences. Each MCMC analysis was terminated at 10 × 106 generations (1 tree saved every 1,000 generations), when the average standard deviation of split frequencies (SDSF) was <0.004 across runs. The first 25% of generations (including all with SDSF ≥0.01) were discarded as burn-in. Posterior probabilities for each clade were obtained from a 50% majority-rule consensus of the approximately 40,000 retained trees. Nonparametric bootstrapping (10,000 replicates) of the full dataset using maximum parsimony (MP) was also implemented, using PAUP* (54), with addseq = simple, swap = TBR, and maxtrees = 1 (see ref. 55). Although the entire dataset was used to obtain the best estimate of phylogeny, only the ITS partition was used for comparative analyses (all dependent on branch lengths), based on missing ETS and trnK data for some taxa in the dataset and evidence for relatively clock-like evolution of ITS sequences in angiosperms (56). Unconstrained branch lengths were used for analyses involving Pagel's Continuous program because model B of Continuous cannot be used with ultrametric trees (57–59). Ultrametric trees were used for analysis of binary traits under the assumption that molecular branch lengths involving neutral (or nearly neutral) substitutions in gene spacers or introns are most meaningful for studies of phenotypic evolution if they reflect relative time (i.e., are ultrametric). To obtain ultrametric trees, ITS data were analyzed using BEAST v1.4 (60) under a relaxed clock (uncorrelated lognormal; ref. 61), Yule process of speciation, and best-fit model of sequence evolution for ITS (GTR+I+Γ; see above), with 4 γ categories and constrained monophyly of Dalechampia. Each of 4 independent MCMC analyses was terminated at 30 × 106 generations (saving 1 tree per 4,000 generations), when TRACER v1.4 (62) indicated that the effective sample size of the posterior distribution was >1,000 (1,183.8 to 1,876.5) across runs, with a burn-in of 25%. The 4 post–burn-in posterior distributions were combined (22,500 trees total) and resampled every 100,000 generations using LogCombiner v1.4.8 (in BEAST package; ref. 60) in preparation for use in BayesTraits. To obtain nonultrametric trees for comparative analyses of continuous characters in BayesTraits, ITS data alone were analyzed using 4 independent runs of MrBayes, as in the combined-data analyses, with termination at 15 × 106 generations (SDSF <0.006) and a burn-in of 32.5%.

Analyses of Trait Evolution.

The sequence of evolutionary change in binary defensive and pollination traits was estimated by optimizing traits using ML optimization in Mesquite (63). MP optimization was used for multistate traits (Fig. 2) and graphic display of binary-trait change (Fig. S2) but not for analysis or interpretation. Statistical analyses of correlated trait evolution, order of trait change, and the influence of the state of one trait on the probability of evolutionary change in the other were based on the Ominibus, Order, and Contingency tests, respectively, in BayesTraits-Discrete (18, 58). BayesTraits-Continuous (57, 59) was used to assess patterns of total defense evolution, whereby number of lines of defense was treated as a continuous trait (although actually ordinal, with 9 states). See Agrawal et al. (24) for a clear explanation of analyses and interpretation of parameters.

To assess whether any defense or pollination innovations had effects on rates of speciation, extinction, or net diversification, we estimated these parameters with BiSSE (64) as implemented in Mesquite (63). However, we found no significant effects of character state on these parameter estimates. This nonsignificant result indicates that our BayesTraits analyses were unlikely to have been compromised by biased sampling caused by diversification or extinction rates being strongly influenced by character state (see ref. 65).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Bridget Wessa for help in DNA sequencing; Michael Park and Wayne Pfeiffer for analytical assistance; numerous graduate and postdoctoral students for help in the field, greenhouse, and laboratory; and David Ackerly and 3 anonymous reviewers for comments on earlier drafts. Funding was provided by National Science Foundation Grants DEB-9020265, -9318640, -9596019, and -0444745).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. A.A.A. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0907051106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Strauss SY, Armbruster WS. Linking herbivory and pollination—new perspectives on plant and animal ecology and evolution. Ecology. 1997;78:1617–1618. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strauss SY, Conner JK, Rush SL. Foliar herbivory affects floral characters and plant attractiveness to pollinators: Implications for male and female plant fitness. Am Naturalist. 1996;147:1098–1107. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strauss SY. Floral characters link herbivores, pollinators, and plant fitness. Ecology. 1997;78:1640–1645. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armbruster WS. Can indirect selection and genetic context contribute to trait diversification? A transition-probability study of blossom-colour evolution in two genera. J Evol Biol. 2002;15:468–486. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Irwin RE, Strauss SY. Flower color microevolution in wild radish: Evolutionary response to pollinator-mediated selection. Am Naturalist. 2005;165:225–237. doi: 10.1086/426714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coberly LC, Rausher MD. Pleiotropic effects of an allele producing white flowers in Ipomoea purpurea. Evolution. 2008;62:1076–1085. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rausher MD. Evolutionary transitions in floral color. Int J Plant Sci. 2008;169:7–21. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faegri K, van der Pijl L. The Principles of Pollination Ecology. Oxford: Pergamon; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simpson GG. Tempo and Mode in Evolution. New York: Columbia Univ Press; 1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ehrlich PR, Raven PH. Butterflies and plant: A study in coevolution. Evolution. 1964;18:586–608. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vermeij GJ. The evolutionary interaction among species: Selection, escalation, and coevolution. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1994;25:219–236. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams GC. Natural Selection. Domain, Levels, and Challenges. Oxford: Oxford Univ Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gould SJ, Vrba ES. Exaptation—a missing term in the science of form. Paleobiology. 1982;8:4–15. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gould SJ. Evolution and the triumph of homology, or why history matters. Am Scientist. 1986;74:60–69. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gould SJ. The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Felsenstein J. Phylogenies and the comparative method. Am Naturalist. 1985;125:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harvey PH, Pagel MD. The Comparative Method in Evolutionary Biology. Oxford: Oxford Univ Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pagel MD. Detecting correlated evolution on phylogenies: A general model for comparative analysis of discrete characters. Proc R Soc London B. 1994;255:37–45. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stiassny MLJ. Atavisms, phylogenetic character reversals, and the origin of evolutionary novelties. Netherlands J Zool. 1992;42:260–276. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shubin N, Wake DB, Crawford AJ. Morphological variation in the limbs of Taricha granulosa (Caudata, Salamandridae)—evolutionary and phylogenetic implications. Evolution. 1995;49:874–884. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1995.tb02323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Costa MMR, Fox S, Hanna AI, Baxter C, Coen E. Evolution of regulatory interactions controlling floral asymmetry. Development. 2005;132:5093–5101. doi: 10.1242/dev.02085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agrawal AA. Macroevolution of plant defense strategies. Trends Ecol Evol. 2007;22:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agrawal AA, Fishbein M. Phylogenetic escalation and decline of plant defense strategies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:10057–10060. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802368105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agrawal AA, Salminen JP, Fishbein M. Phylogenetic trends in phenolic metabolism of milkweeds (Asclepias): Evidence for escalation. Evolution. 2009;63:663–673. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becerra JX. Insects on plants: Macroevolutionary chemical trends in host use. Science. 1997;276:253–256. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5310.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson JN. The Geographic Mosaic of Coevolution. Chicago: Univ Chicago Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pellmyr O, Thien LB. Insect reproduction and floral fragrances—keys to the evolution of the angiosperms. Taxon. 1986;35:76–85. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arnold EN. Investigating the origins of performance advantage: Adaptation, exaptation and lineage effects. In: Eggleton P, Vane-Wright R, editors. Phylogenetics and Ecology. London: Academic; 1994. pp. 123–168. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lev-Yadun S, Ne'eman G, Shanas U. A sheep in wolf's clothing: Do carrion and dung odours of flowers not only attract pollinators but also deter herbivores? Bioessays. 2009;31:84–88. doi: 10.1002/bies.070191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Armbruster WS. Evolution of floral morphology and function: An integrated approach to adaptation, constraint, and compromise in Dalechampia (Euphorbiaceae) In: Lloyd D, Barrett SCH, editors. Floral Biology. New York: Chapman & Hall; 1996. pp. 241–272. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Armbruster WS. The role of resin in angiosperm pollination: Ecological and chemical considerations. Am J Bot. 1984;71:1149–1160. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Armbruster WS, et al. Do biochemical exaptations link evolution of plant defense and pollination systems? Historical hypotheses and experimental tests with Dalechampia vines. Am Naturalist. 1997;149:461–484. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Armbruster WS. Exaptations link the evolution of plant-herbivore and plant-pollinator interactions: A phylogenetic inquiry. Ecology. 1997;78:1661–1674. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Armbruster WS, Baldwin BG. Switch from specialized to generalized pollination. Nature. 1998;394:632. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Armbruster WS. Evolution of plant pollination systems: Hypotheses and tests with the neotropical vine Dalechampia. Evolution. 1993;47:1480–1505. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1993.tb02170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Armbruster WS, Mziray WR. Pollination and herbivore ecology of an African Dalechampia (Euphorbiaceae): Comparisons with New World species. Biotropica. 1987;19:64–73. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Armbruster WS, Herzig AL, Clausen TP. Pollination of two sympatric species of Dalechampia (Euphorbiaceae) in Suriname by male euglossine bees. Am J Bot. 1992;79:1374–1381. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whitten WM, et al. Carvone oxide: An example of convergent evolution in euglossine-pollinated plants. Syst Bot. 1986;11:222–228. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Armbruster WS, Keller CS, Matsuki M, Clausen TP. Pollination of Dalechampia magnoliifolia (Euphorbiaceae) by male euglossine bees (Apidae: Euglossini) Am J Bot. 1989;76:1279–1285. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Armbruster WS, Antonsen L, Pélabon C. Phenotypic selection on Dalechampia blossoms: Honest signaling affects pollination success. Ecology. 2005;86:3323–3333. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Armbruster WS, Hansen TF, Pélabon C, Pérez-Barrales R, Maad J. The adaptive accuracy of flowers: Measurement and microevolutionary patterns. Ann Bot. 2009;103:1529–1545. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcp095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Armbruster WS, Hansen TF, Pélabon C, Bolstad G. Macroevolutionary patterns of pollination accuracy: A comparison of three genera. New Phytologist. 2009;183:600–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feeney P. Plant apparency and chemical defense. Recent Advances Phytochem. 1976;10:1–40. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Webster GL, Armbruster WS. A synopsis of the neotropical species of Dalechampia. Bot J Linn Soc. 1991;105:137–177. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Armbruster WS. Cladistic analysis and revision of Dalechampia sections Rhopalostylis and Brevicolumnae (Euphorbiaceae) Syst Bot. 1996;21:209–235. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Doyle JJ, Doyle JL. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem Bull. 1987;19:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Steele KP, Vilgalys R. Phylogenetic analyses of Polemoniaceae using nucleotide sequences of the plastid gene matK. Syst Bot. 1994;19:126–142. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baldwin BG, Markos S. Phylogenetic utility of the external transcribed spacer (ETS) of 18S–26S rDNA: Congruence of ETS and ITS trees of Calycadenia (Compositae) Mol Phylogenet Evol. 1998;10:449–463. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1998.0545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baldwin BG, Wessa BL. Origin and relationships of the tarweed-silversword lineage (Compositae—-Madiinae) Am J Bot. 2000;87:1890–1908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Galtier N, Gouy M, Gautier C. SeaView and Phylo_win, two graphic tools for sequence alignment and molecular phylogeny. Comput Applic Biosci. 1996;12:543–548. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.6.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: A multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinform. 2004;5:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nylander JAA. MrModeltest 2.3. Program distributed by the author. Uppsala, Sweden: Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Swofford DL. PAUP*. Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods), v. 4.0 beta 10. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Müller KF. The efficiency of different search strategies in estimating parsimony jackknife, bootstrap, and Bremer support. BMC Evol Biol. 2005;5:58. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-5-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kay KM, Whittall JB, Hodges SA. A survey of nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer substitution rates across angiosperms: An approximate molecular clock with life history effects. BMC Evol Biol. 2006;6:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-6-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pagel MD, Meade A. BayesTraits. 2007. [Accessed June 1, 2009]. Available at http://www.evolution.reading.ac.uk/BayesTraits.html.

- 58.Pagel M. Inferring evolutionary processes from phylogenies. Zoologica Scripta. 1997;26:331–348. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pagel M. Inferring the historical patterns of biological evolution. Nature. 1999;401:877–884. doi: 10.1038/44766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Drummond AJ, Rambaut A BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:214. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Drummond AJ, Ho SYW, Phillips MJ, Rambaut A. Relaxed phylogenetics and dating with confidence. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e88. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rambaut A, Drummond AJ. TRACER v1.4. 2007. [Accessed June 15, 2009]. Available at http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/tracer/

- 63.Maddison WP, Maddison DR. Mesquite: A modular system for evolutionary analysis, version 2.6. 2009. Available at http://mesquiteproject.org (program updated on April 20, 2009, run on Dell Latitude C400)

- 64.Maddison WP, Midford PE, Otto SP. Estimating a binary character's effect on speciation and extinction. Syst Biol. 2007;56:701–710. doi: 10.1080/10635150701607033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nosil P, Mooers AO. Testing hypotheses about ecological specialization using phylogenetic trees. Evolution. 2005;59:2256–2263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.