Abstract

Although the molecular clock hypothesis posits that the rate of molecular change is constant over time, there is evidence that rates vary among lineages. Some of the strongest evidence for variable molecular rates comes from the primates; e.g., the “hominoid slowdown.” These rate differences are hypothesized to correlate with certain species attributes, such as generation time and body size. Here, we examine rates of molecular change in the strepsirrhine suborder of primates and test whether body size or age at first reproduction (a proxy for generation time) explains patterns of rate variation better than a null model where the molecular clock is independent of these factors. To examine these models, we analyzed DNA sequences from four pairs of recently diverged strepsirrhine sister taxa to estimate molecular rates by using sign tests, likelihood ratio tests, and regression analyses. Our analysis does not support a model where body weight or age at first reproduction strongly influences rates of molecular evolution across mitochondrial and nuclear sites. Instead, our analysis supports a model where age at first reproduction influences neutral evolution in the nuclear genome. This study supports the generation time hypothesis for rate variation in the nuclear molecular clock. Molecular clock variation due to generation time may help to resolve the discordance between molecular and paleontological estimates for divergence date estimates in primate evolution.

Keywords: evolution, primates, generation time, body size, strepsirhine

According to the molecular clock hypothesis, the rate of molecular evolution is constant over time and across lineages (1). The molecular clock can be used to generate a rate of molecular change per unit of time that can be applied across a phylogenetic tree to estimate ordinal times for phylogenetic nodes. Indeed, the molecular clock has been widely used to estimate divergence times (2). One problem in the application of molecular clocks is rate variation; i.e., there is not a universal molecular clock. For example, rodents have a faster substitution rate than primates (3, 4), and hominoids have a slower rate of molecular evolution than other primates, a phenomenon called the “hominoid slowdown” (5–10). These findings have prompted development of methods for using the molecular clock to date nodes despite rate variation (5, 11–15). Although useful for estimating dates, these methods do not directly address hypotheses for the underlying causes of variation in molecular rates between lineages. Here, we examine available DNA sequence data from strepsirrhine primates to test whether the generation time (GT) hypothesis or the body size (BS) hypothesis better explains rate variation in the molecular clock. An understanding of the underlying cause of rate variation would assist both in understanding the causes of mutation and in refining molecular dating approaches.

There is evidence that aspects of an organism's phenotype correlate with its substitution rate, especially GT (3, 7, 16–18) and BS (19–22). Currently, there is no consensus as to whether the GT or BS hypothesis is a better fit to the observed variation in evolutionary rates (ref. 23, p. 224). The GT hypothesis posits that the rate of molecular evolution is inversely correlated with GT; e.g., species with longer GTs will exhibit slower rates of molecular evolution. The GT hypothesis assumes that most germ-line mutations occur during DNA replication. Species with longer generations go through fewer DNA replications and accumulate fewer mutations due to replication errors. Many studies have invoked the GT hypothesis to explain rate variation (3, 4, 6–8, 10, 18, 24–27). The BS hypothesis posits that smaller species have higher mass-specific metabolic rates and, as a consequence, have a higher rate of DNA damage from oxygen radicals that are a byproduct of metabolic processes (19). In the BS hypothesis, species with a larger BS will exhibit slower rates of molecular evolution. Evidence supporting the BS hypothesis comes from work across a very broad range of taxa (19, 21, 22, 28), although the effect has been disputed (29–31).

Few studies have tested between these two competing hypotheses. This is partly because of the strong correlations between BS, basal metabolic rate, and GT; e.g., mammals with relatively larger BSs usually have longer GTs and a lower basal metabolic rate. Of the work that has addressed the alternatives, Mooers and Harvey (32) found that age at first birth in birds was significantly related to the rate of molecular evolution in DNA–DNA hybridization data, but BS was not. A genome-scale study in mammals found that GT better explained variation in base pair substitutions than a BS model (18). Other studies of molecular rates within mammals have found an effect of both BS and generation length (20, 33). Most of these studies, however, examined the effect of GT or BS along very long phylogenetic branches. With long branches, it is not clear that the extant members of a lineage are representative of a lineage's entire history. In the present study, we tested between the BS and GT hypotheses by using the strepsirrhine suborder of primates as a model system. The strepsirrhines are advantageous for testing between the BS and GT hypotheses for a number of reasons. First, the strepsirrhines are a diverse radiation with four sets of sister taxa that have clear BS differences (Fig. 1). Second, each of these sister pairs has a fairly recent last common ancestor (<15 Ma) (34), and the phenotypic distribution of these features in extant strepsirrhines suggests that the relevant phenotypic difference has been directional. Third, in one of these sets of sister taxa, the larger taxon has a faster life history, a departure from the usual circumstances, where the species with larger BS has a slower life history. This will assist in enabling a test of the BS and GT hypotheses. Fourth, an extensive DNA sequence dataset can be aggregated for strepsirrhines from a recent study (34) and GenBank, totaling 23 different DNA sets. These datasets are from mtDNA genes and nuclear introns, exons, and an intergenic region.

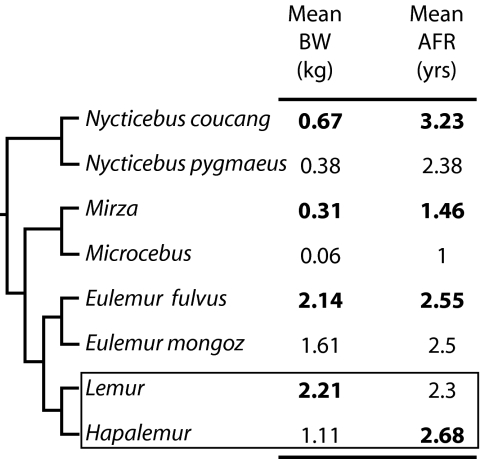

Fig. 1.

Taxonomically reduced strepsirrhine phylogeny showing four pairs of taxa and their body weight and AFR. For each species, mean body weights and mean AFR are given at right; sources are listed in Methods. For each pair, the estimate for BS and AFR that is consistent with a slower molecular clock under the BS and GT hypotheses is in bold. The pair with an unexpected relationship between AFR and BS (Lemur and Hapalemur) is highlighted with a box. A heuristic phylogenetic analysis suggests the following phylogenetic changes within these pairs: Since the last common ancestor (LCA) of N. coucang and N. pygmaeus, N. coucang has evolved a longer AFR and larger BS, whereas N. pygmaeus has evolved relatively conservatively since their LCA (based on a Loris tardigradus outgroup). Since the LCA of Mirza and Microcebus, Microcebus has evolved a shorter AFR and smaller BS, whereas Mirza has evolved relatively conservatively since their LCA (based on a Cheirogaleus outgroup). Since the LCA of E. fulvus and E. mongoz, E. fulvus currently has evolved a larger BS, whereas E. mongoz has evolved relatively conservatively since their LCA (based on a Eulemur coronatus outgroup). Both E. fulvus and E. mongoz have evolved longer AFRs, based on a Eulemur macaco outgroup. Since the LCA of Lemur and Hapalemur, Hapalemur has evolved a longer AFR, whereas Lemur has evolved conservatively; for BS, Lemur has become larger, and Hapalemur has become smaller (based on a Eulemur outgroup).

Results and Discussion

Branch lengths were estimated for the aggregated datasets for all available sister pairs under two different models of molecular evolution (Table S1 and Table S2). The ratio of branch lengths within each sister pair was assessed for fit to the BS and the GT hypothesis. GT is assessed via age at first reproduction (AFR) (see Methods). Although there is an excess of pairs that fit the BS hypothesis, this relationship is not significantly different from chance for any data partition (Table 1). Considering AFR, when both mtDNA and nuclear DNA (nDNA) noncoding data partitions are included, there is an excess of pairs that fit the GT model, where the greater AFR species has the shorter branch length (Table 2). This effect held under both models of molecular evolution, both with zero branch length pairs excluded and included. There is no relationship between AFR and first and second codon positions. When mtDNA and nDNA are considered separately, there is no relationship between AFR in the mtDNA data partitions. For nDNA, within the noncoding data partitions, there is an excess of long branches and shorter AFR under the GTR+Γ+I and ML models, with zero-branch length pairs both excluded and included.

Table 1.

Body size and branch length binomial tests

| Branch lengths (BLs) included and genome region* | Positions | GTR+Γ+I model |

ML model |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of comparisons | No. of fits BS | P | No. of comparisons | No. of fits BS | P | ||

| No-zero BLs | |||||||

| All | First, second, and functional | 26 | 14 | 0.423 | 25 | 14 | 0.345 |

| Third, introns, and intergenic | 55 | 30 | 0.295 | 59 | 33 | 0.217 | |

| Nuclear | First, second, and functional | 9 | 6 | 0.254 | 9 | 6 | 0.254 |

| Third, introns, and intergenic | 46 | 25 | 0.329 | 48 | 27 | 0.235 | |

| Mitochondrial | First, second, and functional | 17 | 8 | 0.500 | 16 | 8 | 0.598 |

| Third | 9 | 5 | 0.500 | 11 | 6 | 0.500 | |

| All BLs | |||||||

| All | First, second, and functional | 35 | 19 | 0.368 | 35 | 20 | 0.250 |

| Third, introns, and intergenic | 69 | 38 | 0.235 | 71 | 39 | 0.238 | |

| Nuclear | First and second | 16 | 9 | 0.402 | 16 | 9 | 0.402 |

| Third, introns, and intergenic | 58 | 31 | 0.347 | 60 | 33 | 0.259 | |

| Mitochondrial | First, second, and functional | 19 | 10 | 0.500 | 19 | 11 | 0.324 |

| Third | 11 | 7 | 0.274 | 11 | 6 | 0.500 | |

No. of comparisons shows the total number of sister taxa comparisons made, and no. of fits BS indicates the number of sister pairs fitting the BS hypothesis. P values are the one-tailed binomial probability values for the null hypothesis where body size has no relationship to branch length. GTR+Γ+I and ML models are the two different models used for estimating branch lengths. Probabilities of <0.05 represent a departure from the null hypothesis and support for the BS hypothesis.

Table 2.

AFR and branch length binomial tests

| Branch lengths (BLs) included and genome region* | Positions | GTR+Γ+I model |

ML model |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of comparisons | No. of fits AFR | P | No. of comparisons | No. of fits AFR | P | ||

| No zero BLs | |||||||

| All | First, second, and functional | 26 | 14 | 0.423 | 25 | 14 | 0.345 |

| Third, introns, and intergenic | 55 | 35 | 0.029† | 59 | 37 | 0.034† | |

| Nuclear | First and second | 9 | 4 | 0.746 | 9 | 4 | 0.746 |

| Third, introns, and intergenic | 46 | 30 | 0.027† | 48 | 31 | 0.030† | |

| Mitochondrial | First, second, and functional | 17 | 10 | 0.315 | 16 | 10 | 0.227 |

| Third | 9 | 5 | 0.500 | 11 | 6 | 0.500 | |

| All BLs | |||||||

| All | First, second, and functional | 35 | 18 | 0.500 | 35 | 19 | 0.368 |

| Third, introns, and intergenic | 69 | 46 | 0.004‡ | 71 | 44 | 0.028† | |

| Nuclear | First and second | 16 | 6 | 0.895 | 16 | 6 | 0.895 |

| Third, introns, and intergenic | 58 | 39 | 0.006‡ | 60 | 38 | 0.026† | |

| Mitochondrial | First, second, and functional | 19 | 12 | 0.180 | 19 | 13 | 0.084 |

| Third | 11 | 7 | 0.274 | 11 | 6 | 0.500 | |

No. of comparisons shows the total number of sister taxa comparisons made, and no. of fits AFR indicates the number of sister pairs fitting the GT hypothesis. P values are the one-tailed binomial probability values for the null hypothesis where body size has no relationship to branch length. GTR+Γ+I and ML models are the two different models used for estimating branch lengths. Probabilities of <0.05 (†) and <0.01 (‡) represent a departure from the null hypothesis and support for the AFR hypothesis.

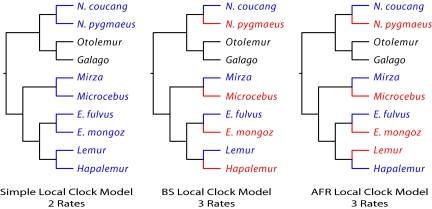

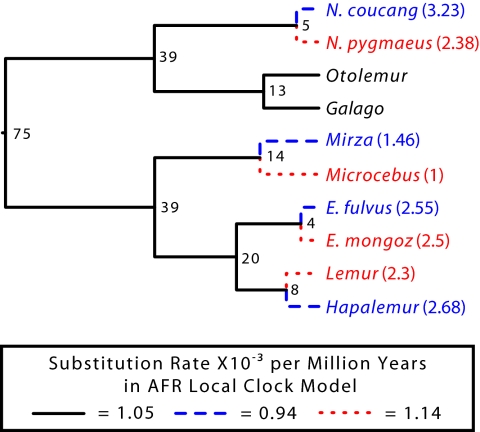

The data partition with the strongest effect, nuclear introns, third positions, and an intergenic region was concatenated into an alignment for testing between the competing GT and BS hypotheses using likelihood ratio tests (LRTs) (35). These tests were based on the likelihoods of three “local clock” models (Fig. 2) (36). First, the likelihood of a tree with two rates of evolution was calculated: one rate for all of the terminal branches of the four sister pairs and a second rate for other branches (simple local clock model). In this model, the sister species have the same rate of evolution. Second, the likelihood of a tree with three rates of evolution was calculated: one rate for the four species predicted to have a slower rate of evolution under the BS model, a second rate for the four species predicted to have a faster rate of evolution under the BS model, and a third rate for all remaining branches (BS local clock model). Third, the likelihood of a tree with three rates was calculated: one evolutionary rate for the four species predicted to have a slower rate of evolution under the AFR model, a second rate for each of the terminal branches of the sister pairs predicted to have a faster rate of evolution under the AFR model, and a third rate for all remaining branches (AFR local clock model). The LRTs among these models show that there is not a significant difference between the simple local clock model and the BS local clock model (Table 2). Therefore, the more parsimonious simple local clock model is the favored alternative. The AFR local clock model, however, is a significantly better fit than the simple local clock model in all LRTs (save one with a probability just over 0.05). The AFR local clock model is the best fit among these three models, signifying that inclusion of AFR data into molecular analyses is preferred over the omission of such data and also preferred to the inclusion of BS. Furthermore, when AFR local clock models incorporate date estimates, the molecular rate in the species with shorter AFRs is ≈20% faster than in the species with the longer AFRs (Fig. 3). These analyses strongly support the GT hypothesis for molecular rate variation in the neutral nuclear molecular clock of strepsirrhines.

Fig. 2.

Local clock models described in the text. Different colors correspond to different rates.

Fig. 3.

Estimated substitution rates among the three local clocks in the AFR local clock model. This is the model that best fit the dataset as described in text. Numbers appearing at the nodes are dates in millions of years. Numbers in parentheses following taxon names are AFRs in years. Rates are from the AFR local clock model using the GTR+Γ5 model with the concatenated nuclear third position, intron, and intergenic region dataset (Table 3). In this model, three rates are estimated: blue dashed lines are species predicted to have a slower rate of molecular evolution due to their higher AFR; red dotted lines are species predicted to have a faster rate of molecular evolution due to their lower AFR; and black lines have a third rate. The estimated molecular rates of the local clocks fit the expectations of the GT hypothesis.

Table 3.

Likelihood ratio tests

| HKY+Γ5 |

GTR+Γ5 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With dates |

Without dates |

With dates |

Without dates |

|||||

| lnL | No. of parameters | lnL | No. of parameters | lnL | No. of parameters | lnL | No. of parameters | |

| Likelihoods* | ||||||||

| Simple local clock model | −28172.62612 | 4 | −28145.78297 | 12 | −28143.18565 | 8 | −28116.3325 | 16 |

| BS local clock model | −28172.33331 | 5 | −28145.53381 | 13 | −28142.90511 | 9 | −28116.09223 | 17 |

| AFR local clock model | −28170.54459 | 5 | −28143.8477 | 13 | −28141.12975 | 9 | −28114.4185 | 17 |

| LRT P values† | ||||||||

| Simple vs. BS model | 0.4441 | 0.4802 | 0.4538 | 0.4882 | ||||

| Simple vs. AFR model | 0.0413‡ | 0.0491‡ | 0.0426‡ | 0.0504§ | ||||

*Likelihood values for the models described in text.

†Probability values for the LRTs described in text.

‡P < 0.05.

§Value was very near to 0.05.

Regression was conducted from contrasts of branch length and BS and AFR to further explore the relationship of BS and AFR. Neither BS nor AFR recovered a significant regression for the datasets with the strongest effect in the sign tests (nuclear introns, third positions, and intergenic; GTR+Γ+I model; BS, F = 1.5, P = 0.23, 1 df; and AFR, F = 0.47, P = 0.23, 1 df; Fig. S1). This suggests that the effect of AFR is not strong, that more data are required to achieve the statistical power to detect an effect with a regression, or both.

The present analyses support the GT hypothesis as an explanation for molecular rate variation in the neutral nuclear molecular clock of strepsirrhines. The BS hypothesis does not explain rate variation in strepsirrhines. Because of the correlation between life history and BS, it is often difficult to decipher whether one of these variables is determinant (20). For example, the cause of the hominoid slowdown is difficult to resolve because the hominoids have both larger BS and slower life history than Old World monkeys. If the present results are extendable, they support GT as the primary factor explaining rate variation in the nuclear molecular clock (3, 4, 6–8, 18, 26).

This analysis provides support for differential causes of rate variation in mtDNA and nDNA (33). This may owe to its unique features relative to nDNA. One hypothesis is that mtDNA rates are nevertheless related to GT, but that the maternal inheritance of mtDNA significantly reduces the influence of GT (37). This is because the mechanism behind the GT hypothesis predicts that males are the likely source of mutations (the “male-driven model”) (37, 53). A second hypothesis is that mtDNA substitution rates are linked to aging (i.e., the longevity hypothesis) (33, 38), although this may not explain patterns in primates and their relatives (33). We did not examine maximum age as a variable and cannot test this hypothesis. An additional possibility is that rates in mtDNA are related to these factors or others, but there are not enough data in the present analysis to resolve the question.

Rate variation from any cause has important consequences for dating divergences by using molecular clocks. Given the widespread use of molecular clocks for dating divergences between species, it is critical to better understand the underlying causes of rate variation. Current molecular dating methodologies are indifferent to the cause of rate variation, instead using analytical approaches to allow for the estimation of divergence dates despite the effect (5, 11–15). Optimally, phenotypic attributes of living and fossil organisms can assist in “correcting” rates, thereby yielding date estimates that are both more accurate and more precise (21). The present study supports this idea but suggests that it is an organism's life history that is the critical factor to correcting nuclear molecular rates. In the present study, the regression analyses show that too few data were available to generate such correction factors, although genomic scale analyses suggest that these approaches may be possible (6).

The present conclusions support the idea that discord between fossil and molecular estimates for divergence dates can be resolved if there have been pervasive changes in a lineage's life history over evolutionary time. For example, if early mammals had faster life histories, this would result in a faster molecular clock. This could solve differences in molecular and paleontological estimates for the origin of mammals because the deeper branches in the tree would have a faster rate of molecular evolution than estimated from extant species (39). The GT hypothesis may be especially useful in explaining the considerable discord in dates derived from fossil and molecular data for primates (40) because BS in crown primates may not have changed significantly over evolutionary history (41). If molecular rate variation is instead tied to GT, changes in primate life history over evolutionary time could resolve the discord between molecular and paleontological estimates of primate divergence dates. Further study of the relationship between GT, AFR, and other aspects of life history will be required to increase our understanding of these variables and their interrelationships. Studies that address life history evolution across living and fossil taxa will be exceptionally useful in further understanding the role of GT in the primate molecular clock.

Methods

Species Pairs Examined.

We examined a recent molecular phylogeny of strepsirrhines (34) for sister pairs of taxa with nonoverlapping BSs. Average BSs were calculated from the sample sizes and mass estimates reported in Smith and Jungers (42). Minimum and maximum BS values were noted for each of the species in a particular pair. When the range of BS estimates of one species largely overlapped the range of BS estimates of the other, they were excluded from the analysis, ensuring that the species chosen had different BSs. Based on this criterion, five pairs were recovered: Nycticebus coucang/Nycticebus pygmaeus, Lemur/Hapalemur, Eulemur fulvus/Eulemur mongoz, Mirza/Microcebus, and Otolemur/Galago. The phylogeny of the lorisiforms suggests that Otolemur and Galago are not sister taxa (43), which led us to discard this pair for analysis, although the sequences remained part of the alignment. This yielded four pairs of phylogenetically independent contrasts (Fig. 1). As a proxy for GT, estimates for female AFR were used. The values for AFR were taken as averages from Kappeler and Pereira (44), except for N. coucang and N. pygmaeus. Data for Nycticebus were from the husbandry manual of Fitch-Snyder and Schulze (45) because it provides an estimate for both N. coucang and N. pygmaeus.

Genetic Dataset.

A total of 23 gene regions were extracted from GenBank (Table S3). In total, there were 11 intronic, 5 exonic, 1 intergenic, and 6 mitochondrial regions. For each gene region, Homo and Pan were included as outgroups.

Estimation of Substitution Rate.

Nearly all sequences were aligned by using ClustalW (46). Interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein was aligned from the translated amino acid sequence by using MEGA (47). Alignments of the mtDNA coding regions resulted in ORFs, supporting their authenticity as mtDNA sequences and not nuclear introgressions (numts). All alignments were further refined by eye. Maximum-likelihood branch lengths were estimated by PAUP* version 4.0 beta10 (48) given a taxonomically restricted phylogeny based on Horvath et al. (34) (Fig. 1). For each dataset, branch lengths were calculated under two models. One was a model without a molecular clock, estimating all parameters of a general time-reversible plus gamma plus invariant sites (GTR+Γ+I), including base frequencies, and the second model was the maximum-likelihood (ML) model estimated from Modeltest (49).

Statistical Analysis.

At each gene, for each sister pair there are two phylogenetically independent branches; unless they are equal, one branch is longer, and one branch is shorter. Because these branches derive from a single common ancestor, they represent the same length of ordinal time. Given this, at each gene, the longer branch represents a faster rate of evolution, and the shorter branch represents a slower rate of evolution. The null hypothesis is that there is no association between BS or AFR and the long or short branch for each gene. The long or short branch is equally probable (i.e., has a chance association with BS or AFR similar to a coin toss). We therefore modeled the probability distribution of long- and short-branch lengths by using a sign test (a binomial test with P = 0.5). According to the BS hypothesis, for each gene the larger species is expected to be the shorter branch; i.e., have a slower rate of molecular evolution. Given this a priori hypothesis, a one-tailed test was used to detect an excess of longer branches associated with the smaller species. According to the GT hypothesis, the species with a greater AFR is expected to be the shorter branch; i.e., have a slower rate of molecular evolution. Given this a priori hypothesis, a one-tailed test was used to detect for an excess of longer branches associated with the shorter AFR species. This test was done on branch lengths for each gene from the GTR+Γ+I and the ML models. Regression was conducted on the contrasts between branch lengths (BLs) in each sister pair [ln(BLspecies A/BLspecies B)] against the contrasts in BS [ln(BSA/BSB)] and AFR [ln(AFRA/AFRB)]. Regression lines were forced through the origin. These statistical methods follow those of others (31, 50, 51).

Because there is evidence that molecular rates may differ between mtDNA and nDNA and between coding and noncoding positions (33), the binomial test was conducted on the following data partitions: mtDNA coding plus functional genes (comprising first codon position, second codon position, 12S, 16S, and tRNA), mtDNA noncoding (comprising third codon positions), nDNA coding genes (comprising first and second codon positions), and nDNA noncoding genes (third codon position, introns, and intergenic regions). For each gene, there are up to four pairs analyzed. In a number of cases, there were terminal branches of zero length. We repeated the sign tests twice, once omitting all pairs that had zero branch lengths from the analysis and a second time including branches of zero length as the shorter branch. Pairs with zero branch lengths were excluded from the regression analysis.

The AFR and BS models were examined via LRTs (35) based on the local clock method (36) using the four pairs of strepsirrhines and Otolemur and Galago for the concatenated nuclear third position and intron dataset (as described above). Likelihoods were calculated with PAML v. 4.2 (52) using both the HKY+Γ5 and GTR+Γ5 models, both without dates and with dates assigned a priori from Horvath et al. (34). In each case, the LRT is based on the test statistic 2ΔlnL, which follows a χ2 distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the difference between the numbers of parameters in the competing models. When a significant difference is detected, the model with the higher likelihood is favored; when a significant difference is not detected, the more parsimonious model is favored (i.e., the model with fewer parameters).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

The authors thank M. Goodman, J. Horvath, D. Pilbeam, W. Qiu, Z. Yang, N. Young, and the anonymous reviewers for comments and suggestions. This work was supported by the Hunter College President's Office (to C.T.) and National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) Grant RR003037. This paper's contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NCRR or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0906686106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Zuckerkandl E, Pauling L. In: Evolving Genes and Proteins. Bryson V, Vogel HJ, editors. New York: Academic; 1965. pp. 97–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hedges SB, Kumar S, editors. The Timetree of Life. Oxford: Oxford Univ Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu CI, Li WH. Evidence for higher rates of nucleotide substitution in rodents than in man. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:1741–1745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.6.1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li WH, Ellsworth DL, Krushkal J, Chang BH, Hewett-Emmett D. Rates of nucleotide substitution in primates and rodents and the generation-time effect hypothesis. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 1996;5:182–187. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1996.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailey WJ, et al. Molecular evolution of the psi eta-globin gene locus: gibbon phylogeny and the hominoid slowdown. Mol Biol Evol. 1991;8:155–184. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elango N, Thomas JW, Yi SV. Variable molecular clocks in hominoids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1370–1375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510716103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodman M. The role of immunochemical differences in the phyletic development of human behavior. Hum Biol. 1961;33:131–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li WH, Tanimura M. The molecular clock runs more slowly in man than in apes and monkeys. Nature. 1987;326:93–96. doi: 10.1038/326093a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steiper ME, Young NM, Sukarna TY. Genomic data support the hominoid slowdown and an Early Oligocene estimate for the hominoid-cercopithecoid divergence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:17021–17026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407270101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yi S, Ellsworth DL, Li WH. Slow molecular clocks in Old World monkeys, apes, and humans. Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19:2191–2198. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drummond AJ, Ho SY, Phillips MJ, Rambaut A. Relaxed phylogenetics and dating with confidence. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e88. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rambaut A, Bromham L. Estimating divergence dates from molecular sequences. Mol Biol Evol. 1998;15:442–448. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanderson MJ. Estimating absolute rates of molecular evolution and divergence times: A penalized likelihood approach. Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19:101–109. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thorne JL, Kishino H. Divergence time and evolutionary rate estimation with multilocus data. Syst Biol. 2002;51:689–702. doi: 10.1080/10635150290102456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thorne JL, Kishino H, Painter IS. Estimating the rate of evolution of the rate of molecular evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 1998;15:1647–1657. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laird CD, McConaughy BL, McCarthy BJ. Rate of fixation of nucleotide substitutions in evolution. Nature. 1969;224:149–154. doi: 10.1038/224149a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li WH, Tanimura M, Sharp PM. An evaluation of the molecular clock hypothesis using mammalian DNA sequences. J Mol Evol. 1987;25:330–342. doi: 10.1007/BF02603118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hwang DG, Green P. Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo sequence analysis reveals varying neutral substitution patterns in mammalian evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13994–14001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404142101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin AP, Palumbi SR. Body size, metabolic rate, generation time, and the molecular clock. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4087–4091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.4087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bromham L, Rambaut A, Harvey PH. Determinants of rate variation in mammalian DNA sequence evolution. J Mol Evol. 1996;43:610–621. doi: 10.1007/BF02202109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gillooly JF, Allen AP, West GB, Brown JH. The rate of DNA evolution: Effects of body size and temperature on the molecular clock. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:140–145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407735101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bromham L. Molecular clocks in reptiles: Life history influences rate of molecular evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19:302–309. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang Z. Computational Molecular Evolution. Oxford: Oxford Univ Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koop BF, Goodman M, Xu P, Chan K, Slightom JL. Primate eta-globin DNA sequences and man's place among the great apes. Nature. 1986;319:234–238. doi: 10.1038/319234a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seino S, Bell GI, Li WH. Sequences of primate insulin genes support the hypothesis of a slower rate of molecular evolution in humans and apes than in monkeys. Mol Biol Evol. 1992;9:193–203. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim SH, Elango N, Warden C, Vigoda E, Yi SV. Heterogeneous genomic molecular clocks in primates. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e163. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gu X, Li WH. Higher rates of amino acid substitution in rodents than in humans. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 1992;1:211–214. doi: 10.1016/1055-7903(92)90017-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fontanillas E, Welch JJ, Thomas JA, Bromham L. The influence of body size and net diversification rate on molecular evolution during the radiation of animal phyla. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:95. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slowinski JB, Arbogast BS. Is the rate of molecular evolution inversely related to body size? Syst Biol. 1999;48:396–399. doi: 10.1080/106351599260364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas JA, Welch JJ, Woolfit M, Bromham L. There is no universal molecular clock for invertebrates, but rate variation does not scale with body size. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7366–7371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510251103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lanfear R, Thomas JA, Welch JJ, Brey T, Bromham L. Metabolic rate does not calibrate the molecular clock. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15388–15393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703359104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mooers AO, Harvey PH. Metabolic rate, generation time, and the rate of molecular evolution in birds. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 1994;3:344–350. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1994.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Welch JJ, Bininda-Emonds OR, Bromham L. Correlates of substitution rate variation in mammalian protein-coding sequences. BMC Evol Biol. 2008;8:53. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horvath JE, et al. Development and application of a phylogenomic toolkit: Resolving the evolutionary history of Madagascar's lemurs. Genome Res. 2008;18:489–499. doi: 10.1101/gr.7265208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Felsenstein J. Evolutionary trees from DNA sequences: A maximum likelihood approach. J Mol Evol. 1981;17:368–376. doi: 10.1007/BF01734359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoder AD, Yang Z. Estimation of primate speciation dates using local molecular clocks. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17:1081–1090. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nabholz B, Mauffrey JF, Bazin E, Galtier N, Glemin S. Determination of mitochondrial genetic diversity in mammals. Genetics. 2008;178:351–361. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.073346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nabholz B, Glemin S, Galtier N. Strong variations of mitochondrial mutation rate across mammals–the longevity hypothesis. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25:120–130. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bromham L. Molecular clocks and explosive radiations. J Mol Evol. 2003;7:S13–S20. doi: 10.1007/s00239-003-0002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steiper ME, Young NM. Timing primate evolution: Lessons from the discordance between molecular and paleontological estimates. Evol Anthropol. 2008;17:179–188. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Soligo C. Correlates of body mass evolution in primates. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2006;130:283–293. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith RJ, Jungers WL. Body mass in comparative primatology. J Hum Evol. 1997;32:523–559. doi: 10.1006/jhev.1996.0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Masters JC, et al. Phylogenetic relationships among the Lorisoidea as indicated by craniodental morphology and mitochondrial sequence data. Am J Primatol. 2007;69:6–15. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kappeler PM, Pereira ME, editors. Primate Life Histories and Socioecology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fitch-Snyder H, Schulze H. In: Management of Lorises in Captivity. A Husbandry Manual for Asian Lorisines (Nycticebus & Loris ssp.) Fitch-Snyder H, Schulze H, editors. San Diego: Center for Reproduction of Endangered Species Zoological Society of San Diego; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swofford DL. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 2001. PAUP*. Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (* and Other Methods) Version 4. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Posada D, Crandall KA. MODELTEST: Testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:817–818. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bromham L, Leys R. Sociality and the rate of molecular evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:1393–1402. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soria-Hernanz DF, Fiz-Palacios O, Braverman JM, Hamilton MB. Reconsidering the generation time hypothesis based on nuclear ribosomal ITS sequence comparisons in annual and perennial angiosperms. BMC Evol Biol. 2008;8:344. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang Z. PAML: A program package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Comput Appl Biosci. 1997;13:555–556. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/13.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shimmin LC, Chang BH, Li WH. Male-driven evolution of DNA sequences. Nature. 1993;362:745–747. doi: 10.1038/362745a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.