Abstract

Schizophrenia, a devastating psychiatric disorder, has a prevalence of 0.5–1%, with high heritability (80–85%) and complex transmission.1 Recent studies implicate rare, large, high-penetrance copy number variants (CNVs) in some cases2, but it is not known what genes or biological mechanisms underlie susceptibility. Here we show that schizophrenia is significantly associated with single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the extended Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) region on chromosome 6. We carried out a genome-wide association study (GWAS) of common SNPs in the Molecular Genetics of Schizophrenia (MGS) case-control sample, and then a meta-analysis of data from the MGS, International Schizophrenia Consortium (ISC) and SGENE datasets. No MGS finding achieved genome-wide statistical significance. In the meta-analysis of European-ancestry subjects (8,008 cases, 19,077 controls), significant association with schizophrenia was observed in a region of linkage disequilibrium on chromosome 6p22.1 (P = 9.54 × 10−9). This region includes a histone gene cluster and several immunity-related genes, possibly implicating etiologic mechanisms involving chromatin modification, transcriptional regulation, auto-immunity and/or infection. These results demonstrate that common schizophrenia susceptibility alleles can be detected. The characterization of these signals will suggest important directions for research on susceptibility mechanisms.

The symptoms and course of schizophrenia are variable, without forming distinct familial subtypes.1 There are positive (delusions, hallucinations), negative (reduced emotions, speech, interest) and disorganized symptoms (disrupted syntax and behavior), as well as mood symptoms in many cases. Onset is typically in adolescence or early adulthood, and rarely in childhood. Course of illness can range from acute episodes with primarily positive symptoms to the more common chronic or relapsing patterns often accompanied by cognitive disability and histories of childhood conduct or developmental disorders.

To search for common schizophrenia susceptibility variants, we carried out a GWAS in cases from three methodologically similar National Institute of Mental Health repository-based studies, and screened controls from the general population. Cases were included with diagnoses of schizophrenia or (in 10% of cases) schizoaffective disorder with the schizophrenia syndrome present for at least six months, genotyped with the Affymetrix 6.0 array. Because the frequencies of tag SNPs and disease susceptibility alleles can vary across populations, we carried out a primary analysis of the larger MGS European-ancestry sample (2,681 cases, 2,653 controls) and then additional analyses of the African American sample (1,286 cases, 973 controls) and of both of these samples combined, to test the hypothesis that there are alleles that influence susceptibility in both populations. All association tests were corrected using principal component scores indexing subjects’ ancestral origins. Genotypic data were imputed for additional HapMap SNPs in selected regions.

These analyses did not produce genome-wide significant findings at a threshold of P < 5 × 10−8 (see Supplementary Methods, p. S16). Table 1 summarizes the best results in the European-ancestry and African American analyses. The strongest genic findings were in CENTG2 (chromosome 2q37.2, P=4.59E-07) in European-ancestry subjects, and in ERBB4 (2q34, P=2.14E-06) in African Americans. Common variants in ERBB4 (the strongest signal in African American subjects) and its ligand neuregulin 1 (NRG1) have been reported to be associated with schizophrenia.3 Additional information about results in previously-reported schizophrenia candidate genes is provided in Supplementary Results 3 and Supplementary Datafile 2.

Table 1.

MGS GWAS results

| SNP | Chromosome/ Band |

Location (BP) |

Odds Ratio |

P-value | Gene(s) | Function/relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| European-ancestry analysis | ||||||

| rs13025591 | 2q37.2 | 236460082 | 1.225 | 4.59E-07 | CENTG2 | GTPase activator; deletions reported in autism cases.12 |

| rs16941261 | 15q25.3 | 86456524 | 1.255 | 8.10E-07 | NTRK3 | Tyrosine receptor kinase; MAPK signaling. |

| rs10140896 | 14q31.3 | 88288291 | 1.216 | 9.49E-07 | EML5 | Microtubule assembly. |

| rs17176973 | 5p15.2 | 10864474 | 1.679 | 2.16E-06 | (50 kb upstream of DAP; mediates interferon-gamma-induced cell death) | |

| rs17833407 | 9p21.3 | 21738320 | 0.804 | 3.02E-06 | (54 kb upstream of MTAP; enzyme involved in polyamine metabolism) | |

| rs1635239 | Xp22.33 | 3242699 | 0.790 | 3.04E-06 | MXRA5 | Cell adhesion protein. |

| rs915071 | 14q12 | 31503609 | 0.834 | 3.94E-06 | (102 kb downstream of NUBPL; nucleotide binding protein-like) | |

| rs11061935 | 12p13.33 | 1684035 | 0.773 | 4.06E-06 | ADIPOR2 | Adiponectin (antidiabetic drug) receptor. |

| rs6809315 | 3q13.11 | 107360155 | 0.828 | 7.58E-06 | ||

| rs1864744 | 14q31.3 | 88020759 | 0.828 | 7.59E-06 | PTPN21 | Regulation of cell growth and differentiation. |

| rs1177749 | 10q23.33 | 97887981 | 0.835 | 1.29E-05 | ZNF518 | Regulation of transcription. |

| rs17619975 | 6p22.3 | 15510731 | 0.611 | 1.49E-05 | JARID2 | Neural tube formation; histone demethylase; adjacent to DTNBP1 (candidate gene). |

| African American analysis | ||||||

| rs1851196 | 2q34 | 212178865 | 0.733 | 2.14E-06 | ERBB4 | Neuregulin receptor. |

| rs3751954 | 17q25.3 | 75368080 | 0.528 | 4.59E-06 | CBX2 | Polycomb protein; histone modfications, maintenance of transcriptional repression. |

| rs10865802 | 3p24.2 | 25039902 | 1.330 | 6.73E-06 | ||

| rs17149424 | 9q34.13 | 134523705 | 1.680 | 8.00E-06 | DDX31 | RNA helicase family; embryogenesis. |

| rs2162361 | 10q23.31 | 90037689 | 2.020 | 9.19E-06 | C10orf59 | Degrades catecholamine in vitro. |

| rs17149524 | 9q34.13 | 134546628 | 1.642 | 9.59E-06 | GTF3C4 | Required for RNA polymerase III function. |

| rs2587562 | 8q13.3 | 73153592 | 1.301 | 1.56E-05 | TRPA1 | Cannabinoid receptor (cannabis may ↑ schizophrenia risk 1); pain, sound perception. |

| rs4316112 | 8p12 | 32539889 | 0.564 | 1.59E-05 | NRG1 | Neuregulin 1; schizophrenia candidate gene; neuronal development. |

| rs4732838 | 8p21.1 | 28098106 | 0.768 | 1.68E-05 | ELP3 | Histone acetyltransferase, RNA Pol III elongator. |

| rs9927946 | 16p13.2 | 8990868 | 0.718 | 1.70E-05 | (26 kb upstream of UPS7; ubiquitin fusion protein cleavage; induction of apoptosis). | |

| rs13065441 | 3q26.2 | 172478029 | 0.626 | 1.94E-05 | TNIK | Stress-activated serine/threonine kinase |

| rs2729993 | 8p12 | 34116593 | 0.687 | 2.14E-05 | ||

Shown are the top 12 results (excluding duplicates -- SNPs in the same genes or regions with less significant results) of the MGS European-ancestry (2681 cases, 2653 controls) and African American (1286 cases, 973 controls) MGS GWAS analyses. Listed are genes within 10 kb of the SNP and annotated information on possible functional relevance; or (in parentheses), information on genes within 150 kb. The odds ratio is for the tested allele (see Supplementary Datafile 2). Supplementary Datafile 1 contains results for all SNPs with P < 0.001, and full gene names. Results of an additional exploratory analysis that combined the two datasets are summarized in Supplementary Results B1b, Table S18 and Supplementary Datafile 1.

As shown in online Table S17, power was adequate in the MGS European-ancestry sample to detect very common risk alleles (30–60% frequency, log additive effects) with genotypic relative risks (GRR) of approximately 1.3, with lower power in the smaller African American sample. The results suggest that there are few or no single common loci with such large effects on risk. The lack of consistency between the European-ancestry and African American analyses could be due to low power, but novel genome-wide analyses presented in the companion paper by the International Schizophrenia Consortium (discussed further below) suggest that while there is substantial overlap between the sets of risk alleles that are detected by GWAS in pairs of European-ancestry samples, much less overlap is seen between European-ancestry and African American samples. This could be because there are actually major differences between the sets of segregating common disease variants in these two populations, and/or because many risk variants are tagged by different GWAS markers or not adequately tagged by the GWAS array, which has poorer coverage of alleles that are more frequent in African populations. The hypothesis underlying our combined analysis, on the other hand, was that there could also be allelic effects common to these populations.

For many common diseases, common risk alleles with GRRs in the range of 1.1–1.2 have been detected when samples were combined to create much larger datasets.4 Therefore, we carried out a meta-analysis of European-ancestry data with two other large studies: the International Schizophrenia Consortium (ISC) (3,322 cases, 3,587 controls) and the SGENE Consortium (2,005 cases, 12,837 controls). Note that because the Aberdeen sample was part of both the ISC and SGENE consortia, Aberdeen data were excluded from SGENE association tests for the meta-analysis. To rapidly identify the regions containing the strongest findings across the three studies (which used several Affymetrix and Illumina genotyping platforms), each group created a list of the SNPs with the best P-values in its final analysis (e.g., those with P<0.001 in MGS), and provided the other groups with its P-values for the SNPs on their lists, based on genotyped or imputed data or data for the best proxy based on LD. Based on these initial results, all available data for genotyped SNPs and imputed HapMap II SNPs were then shared for regions of interest, of which four emerged from the European-ancestry data: 1p21.3 (PTBP2), 4q33 (NEK1), 6p22.1-6p21.31 (extended MHC region) and 18q21.2 (TCF4). We then combined P-values for all SNPs in each region by appropriately weighting Z-scores for sample size, accounting for the direction of association in each sample.

In the meta-analysis of European-ancestry MGS, ISC and SGENE datasets, seven SNPs on chromosome 6p22.1 yielded genome-wide significant evidence for association. These SNPs span 209 kb and are in strong LD (r2>0.9), with substantial LD across 1.5 Mb (Table 2 and Figure 1). Because of the strong LD among these SNPs, it is unclear whether the signal is driven by one or several genes, by intergenic elements, or by longer haplotypes that include susceptibility alleles in many genes. The region includes several types of genes of potential interest. The strongest evidence for association was observed in and near a cluster of histone protein genes, which could be relevant to schizophrenia through their roles in regulation of DNA transcription and repair5,6 or their direct role in antimicrobial defense.7 Other genes in the broad region are involved in chromatin structure (HMGN4), transcriptional regulation (ABT1, ZNF322A, ZNF184), immunity (PRSS16; the butyrophilins8), G-protein-coupled receptor signaling (FKSG83) and in the nuclear pore complex (POM121L2), although the functions of many genes in the region (and of intergenic sequence variants) are not well understood.

Table 2.

Meta-analysis results in the extended MHC I and MHC class II regions

| MGS Freqs | ----------------P-values---------------- | ----Odds Ratios---- | -----Information----- | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rs ID | # | BP | A1/2 | Cont | Case | COMB | MGS | ISC | SGENE | MGS | ISC | SGENE | MGS | ISC | SGENE | Band | Gene(s) (location) |

| rs6939997 | 1 | 25929203 | T/C | 0.089 | 0.080 | 4.90E-07 | 1.40E-01 | 5.66E-04 | 2.85E-04 | 0.900 | 0.785 | 0.712 | 0.978 | 0.851 | 0.955 | 6p22.2 | SLC17A1 (intr) |

| rs13199775 | 2 | 25936761 | T/A | 0.087 | 0.075 | 1.19E-07 | 5.12E-02 | 5.66E-04 | 2.57E-04 | 0.869 | 0.785 | 0.710 | 0.999 | 0.851 | 0.956 | 6p22.2 | SLC17A1 (intr) |

| rs9461219 | 3 | 25944906 | G/C | 0.087 | 0.075 | 4.72E-07 | 4.99E-02 | 2.68E-03 | 2.52E-04 | 0.868 | 0.826 | 0.710 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.956 | 6p22.2 | SLC17A1 (up),SLC17A3 (dwn) |

| rs9467626 | 4 | 25981725 | A/C | 0.091 | 0.080 | 1.65E-07 | 5.32E-02 | 7.47E-04 | 2.68E-04 | 0.872 | 0.784 | 0.710 | 0.988 | 0.806 | 0.959 | 6p22.2 | SLC17A3 (intr) |

| rs2072806 | 5 | 26493072 | G/C | 0.115 | 0.097 | 9.27E-07 | 5.91E-03 | 2.80E-04 | 3.40E-02 | 0.836 | 0.814 | 0.857 | 0.959 | 1.000 | 0.971 | 6p22.1 | BTN3A2 (dwn),BTN2A2 (intr) |

| rs2072803 | 6 | 26500494 | C/G | 0.115 | 0.097 | 8.19E-07 | 5.53E-03 | 2.80E-04 | 3.23E-02 | 0.835 | 0.814 | 0.856 | 0.960 | 1.000 | 0.974 | 6p22.1 | BTN2A2 (intr bound),BTN3A1 (up) |

| rs6904071 | 7 | 27155235 | A/G | 0.186 | 0.166 | 1.78E-08 | 1.21E-02 | 3.03E-04 | 3.72E-04 | 0.879 | 0.819 | 0.799 | 0.987 | 0.851 | 0.988 | 6p22.1 | |

| rs926300 | 8 | 27167422 | T/A | 0.186 | 0.166 | 1.06E-08 | 1.22E-02 | 3.03E-04 | 2.08E-04 | 0.879 | 0.819 | 0.791 | 0.989 | 0.851 | 0.988 | 6p22.1 | |

| rs6913660 | 9 | 27199404 | A/C | 0.184 | 0.164 | 2.36E-08 | 1.71E-02 | 3.03E-04 | 3.35E-04 | 0.884 | 0.819 | 0.798 | 0.998 | 0.851 | 1.000 | 6p22.1 | HIST1H2AG (up),HIST1H2BJ (dwn) |

| rs13219181 | 10 | 27244204 | G/A | 0.183 | 0.163 | 1.29E-08 | 1.47E-02 | 3.03E-04 | 2.05E-04 | 0.881 | 0.819 | 0.791 | 0.983 | 0.851 | 0.989 | 6p22.1 | |

| rs13194053 | 11 | 27251862 | C/T | 0.182 | 0.162 | 9.54E-09 | 1.45E-02 | 3.03E-04 | 1.48E-04 | 0.880 | 0.819 | 0.783 | 0.977 | 0.851 | 0.978 | 6p22.1 | |

| rs13219354 | 12 | 27293643 | C/T | 0.118 | 0.102 | 1.12E-07 | 3.59E-02 | 5.11E-04 | 4.39E-04 | 0.877 | 0.823 | 0.766 | 0.994 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 6p22.1 | |

| rs3800307 | 13 | 27293771 | A/T | 0.205 | 0.183 | 4.35E-08 | 1.34E-02 | 3.35E-03 | 6.12E-05 | 0.886 | 0.880 | 0.787 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.988 | 6p22.1 | |

| rs13212921 | 14 | 27313401 | T/C | 0.124 | 0.108 | 1.28E-07 | 3.09E-02 | 5.76E-04 | 5.53E-04 | 0.873 | 0.823 | 0.770 | 0.960 | 0.940 | 0.968 | 6p22.1 | |

| rs4452638 | 15 | 27337244 | A/G | 0.117 | 0.102 | 2.68E-07 | 4.51E-02 | 3.96E-04 | 1.11E-03 | 0.882 | 0.821 | 0.780 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.987 | 6p22.1 | PRSS16 (dwn) |

| rs6938200 | 16 | 27339129 | G/A | 0.205 | 0.188 | 3.02E-07 | 5.28E-02 | 2.40E-03 | 1.51E-04 | 0.910 | 0.874 | 0.801 | 1.000 | 0.992 | 1.000 | 6p22.1 | PRSS16 (dwn) |

| rs6932590 | 17 | 27356910 | C/T | 0.240 | 0.215 | 7.13E-08 | 3.37E-03 | 2.23E-03 | 8.48E-04 | 0.872 | 0.877 | 0.834 | 0.973 | 0.933 | 1.000 | 6p22.1 | |

| rs3800316 | 18 | 27364081 | C/A | 0.257 | 0.229 | 3.81E-08 | 7.19E-04 | 3.51E-03 | 1.09E-03 | 0.856 | 0.886 | 0.834 | 0.975 | 0.956 | 0.977 | 6p22.1 | |

| rs7746199 | 19 | 27369303 | T/C | 0.185 | 0.160 | 5.03E-08 | 6.85E-04 | 8.77E-04 | 5.70E-03 | 0.837 | 0.859 | 0.839 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 6p22.1 | |

| rs3800318 | 20 | 27371620 | T/A | 0.180 | 0.158 | 6.38E-08 | 2.80E-03 | 8.82E-04 | 2.27E-03 | 0.855 | 0.859 | 0.822 | 0.998 | 1.000 | 0.981 | 6p22.1 | |

| rs16897515 | 21 | 27385999 | A/C | 0.173 | 0.154 | 1.83E-07 | 1.22E-02 | 6.40E-04 | 2.16E-03 | 0.876 | 0.853 | 0.816 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.972 | 6p22.1 | POM121L2 (missense) |

| rs13195040 | 22 | 27521903 | G/A | 0.087 | 0.076 | 2.50E-07 | 1.04E-01 | 3.00E-05 | 2.82E-03 | 0.892 | 0.714 | 0.768 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.983 | 6p22.1 | ZNF184 (dwn) |

| rs10484399 | 23 | 27642507 | G/A | 0.091 | 0.080 | 3.50E-07 | 1.09E-01 | 8.58E-06 | 8.69E-03 | 0.895 | 0.762 | 0.795 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 6p22.1 | |

| rs17693963 | 24 | 27818144 | C/A | 0.101 | 0.085 | 2.81E-07 | 2.87E-02 | 6.00E-05 | 8.85E-03 | 0.864 | 0.781 | 0.795 | 1.000 | 0.993 | 0.986 | 6p22.1 | |

| rs7776351 | 25 | 27834710 | T/C | 0.255 | 0.236 | 3.22E-07 | 2.83E-02 | 1.13E-04 | 6.51E-03 | 0.905 | 0.855 | 0.865 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 6p22.1 | |

| rs12182446 | 26 | 27853717 | A/G | 0.247 | 0.227 | 4.77E-07 | 2.99E-02 | 7.17E-05 | 1.22E-02 | 0.905 | 0.850 | 0.874 | 0.999 | 1.000 | 0.990 | 6p22.1 | |

| rs9272219 | --- | 32710247 | T/G | 0.283 | 0.263 | 6.88E-08 | 1.32E-02 | 2.24E-05 | 1.03E-02 | 0.897 | 0.847 | 0.880 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.977 | 6p21.32 | HLA-DQA1 (up) |

| rs9272535 | --- | 32714734 | A/G | 0.283 | 0.263 | 8.87E-08 | 1.63E-02 | 2.47E-05 | 9.92E-03 | 0.900 | 0.848 | 0.879 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.977 | 6p21.32 | HLA-DQA1 (intr) |

“#” refers to the numbering of SNPs in the LD diagram in Figure 1. “BP” = base pairs. “A1/2” = alleles 1 and 2 (minor/major, forward strand). “Freqs” = minor allele frequencies. “Cont” = controls, “Case” = cases. “COMB” = combined analysis (meta-analysis) of the three datasets. For SNP locations (as reported by snpper.chip.org): “intr”=intron; “up” = upstream (within 10 kb of transcribed sequence) and “dwn”=downstream (within 10 kb); “intr bound” = intron-exon boundary.

Shown are data for all SNPs with P < 10−6 in the extended MHC I and class II MHC regions of chromosome 6p, in the meta-analysis of European-ancestry MGS, ISC and SGENE data (see Table 1 and Supplementary Methods). Odds ratios are reported for the minor allele. Genome-wide significant meta-analysis P-values (P < 5x10−8) are shown in bold italics(see Supplementary Methods, p. S16, regarding this threshold). The information content for the SNP for each study is the imputation r2 reported by MACH 1.0 for MGS; and the PLINK and IMPUTE information measure for ISC and SGENE respectively; “1.000” indicates a SNP that was genotyped or had a perfect proxy. Genes within 10 kb of a SNP are listed; see Figure 1 for additional details for 6p22.1. See Supplementary Datafile 1 for additional meta-analysis results.

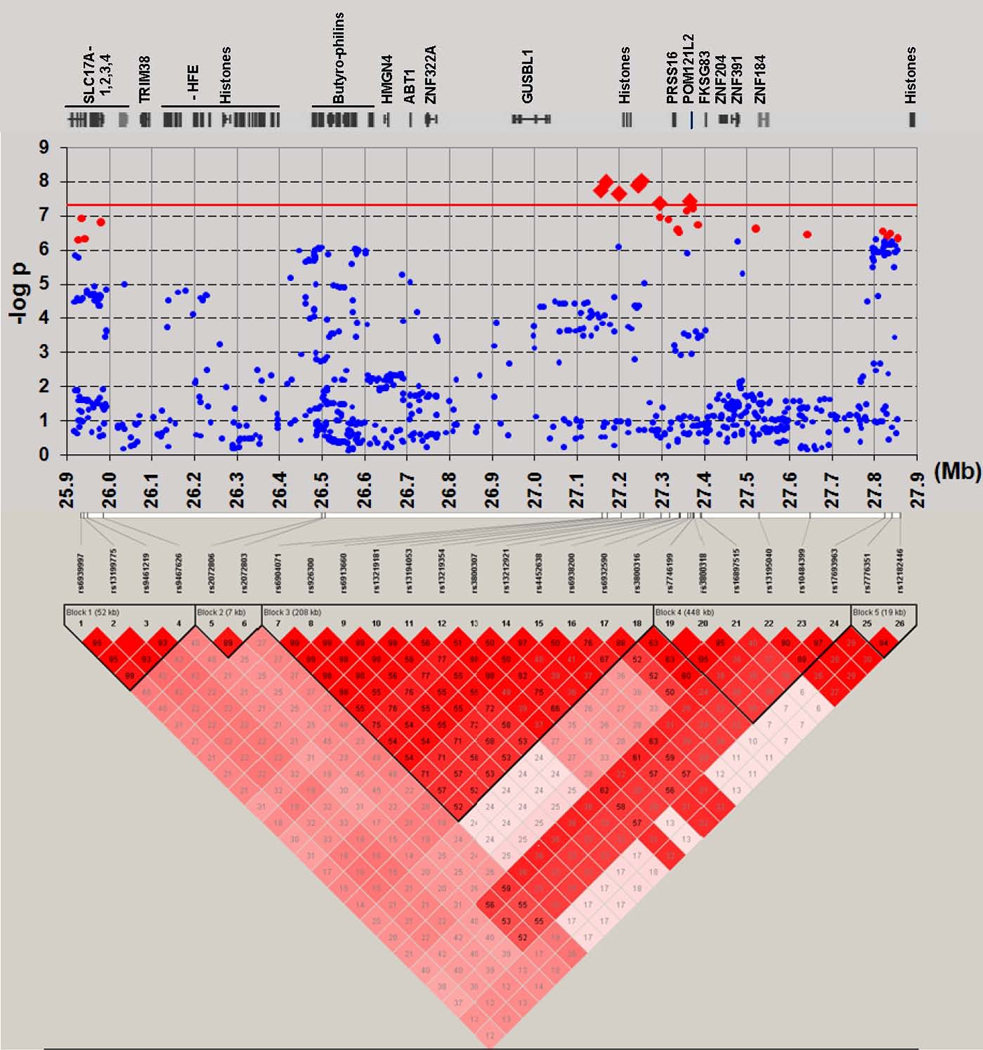

Figure 1. Chromosome 6p22.1 Genetic association and linkage disequilibrium results in European-ancestry samples.

Genome-wide significant evidence for association (P < 5 × 10−8, threshold shown by solid red line, SNPs by large red diamonds) was observed at 7 SNPs across 209 kb. P-values are shown for all genotyped and imputed SNPs (25,900,000–27,875,000 bp) for the meta-analysis of European-ancestry MGS, ISC and SGENE samples (8,008 cases, 19,077 controls). Red circles indicate other SNPs with P < 5 × 10−7. Not shown are two SNPs in HLA-DQA1 (6p21.32; lowest P = 6.88 × 10−8, 32,710,247 bp; see Supplementary Datafile 1). Locations are shown for RefSeq genes and POM121L2. Pairwise LD relationships are shown for 26 SNPs with P < 10−7 (except that SNPs 5 and 6 are shown, despite slightly larger P-values, to illustrate LD for that segment; and a SNP in strong LD with SNPs 25 and 26 is omitted). LD was computed from MGS European-ancestry genotyped and imputed SNP data. The signal is poorly localized because of strong LD: of the 7 significant SNPs, 7–8 and 9–11 are in nearly perfect LD; they are in or within ~ 30–50 kb of a cluster of 5 histone genes (HIST1H2BJ, HIST1H2AG, HIST1H2BK, HIST1H4I, HIST1H2AH; 27,208,073–27,223,325 bp). These SNPs are in moderately strong LD (r2 = 0.52–0.77) with 2 other significant SNPs 70–140 kb away, upstream of PRSS16 (SNP 13) or between PRSS16 and POM121L2 (SNP18). (See Table 2 and Supplementary Figures S10–11 for additional details.)

P-values less than 10−7 were also observed in the meta-analysis in HLA-DQA1 (P = 6.88 × 10−8, Table 2), suggesting autoimmune mechanisms. This gene is in the class II HLA region, which is not in LD with 6p22.1 in the MGS sample. We note also that the MGS GWAS (see Supplementary Datafile 1, European-ancestry results) produced some evidence for association in the FAM69A-EVI-RPL5 gene cluster which has been implicated in multiple sclerosis, a DQA-associated auto-immune disorder.9

Finally, in an analysis reported in the companion paper by the International Schizophrenia Consortium, case-control status in the MGS sample could be predicted with very strong statistical significance based on an aggregate test of large numbers of common alleles, weighted by their odds ratios in the single-SNP association analysis of the ISC sample (please see the ISC paper for details). As expected, results were similar for an analysis with MGS as the discovery sample and ISC as the target (see Supplementary Results 3). As discussed in the ISC paper, the results suggest that a substantial proportion of variance may be explained by many common variants, most of them with small effects that cannot be detected one at a time.

We have identified a region of association of common SNPs with schizophrenia on chromosome 6p22.1. Further research will be required to identify the sequence variation in this region that alters susceptibility, and the mechanisms by which this occurs. The results of this meta-analysis and of the aggregate analysis of multiple alleles reported in the ISC paper strongly suggest that individual common variants have small effects on schizophrenia risk, and that still larger samples may be valuable. The larger goal of research in the field will be to detect and understand the full range of rare and common sequence and structural schizophrenia susceptibility variants. Association findings will advance knowledge of pathophysiological mechanisms, even if they initially explain small proportions of genetic variance. Future advances in knowledge of gene and protein functions and interactions should make it possible to dissect the functional sets of pathogenic variants based on prior hypotheses.

Methods summary

Details of MGS subject recruitment and sample characteristics are provided in the online Full Methods (section A1). DNA samples were genotyped using the Affymetrix 6.0 array at the Broad Institute. Samples (5.3%) were excluded for high missing data rates, outlier proportions of heterozygous genotypes, incorrect sex or genotypic relatedness to other subjects. SNPs (7% for African American, 25% for European-ancestry and 27% for combined analyses) were excluded for minor allele frequencies less than 1%, high missing data rates, Hardy-Weinberg deviation (controls), or excessive Mendelian errors (trios), discordant genotypes (duplicate samples) or large allele frequency differences among DNA plates. Principal component scores reflecting continental and within-Europe ancestries of each subject were computed and outliers excluded. Genomic control λ values for autosomes after QC were 1.042 for African American and 1.087 for the larger European-ancestry and combined analyses.

For MGS, association of single SNPs to schizophrenia was tested by logistic regression (trend test) using PLINK10, separately for European-ancestry, African American and combined datasets, correcting for principal component scores that reflected geographical gradients or that differed between cases and controls, and for sex for chromosome X and pseudoautosomal SNPs. Genotypic data were imputed for 192 regions surrounding the best findings, and for additional regions selected for meta-analysis.11 Detailed results are available in Supplementary Datafiles 1 and 2, and complete results from dbGAP (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=gap).

Meta-analysis of the MGS, ISC and SGENE datasets was carried out by combining P-values for all SNPs (in the selected regions) for which genotyped or imputed data were available for all datasets, with weights computed from case-control sample sizes. See the companion papers for details of the ISC and SGENE analyses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the study participants, and the research staff at the study sites. This study was supported by funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (U.S.A.) and the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression. Genotyping of part of the sample was supported by the Genetic Association Information Network (GAIN), and by The Paul Michael Donovan Charitable Foundation. Genotyping was carried out by the Center for Genotyping and Analysis at the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT with support from the National Center for Research Resources (U.S.A.). The GAIN quality control team (G.R. Abecasis and J. Paschall) made important contributions to the project. We thank S. Purcell for assistance with PLINK.

Footnotes

Full Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Author Contributions J.S., D.F.L., and P.V.G. wrote the first draft of the paper. P.V.G., D.F.L., A.R.S., B.J.M., A.O., F.A., C.R.C., J.M.S., N.G.B., W.F.B., D.W.B., R.R.C., R.F. oversaw the recruitment and clinical assessment of MGS participants and the clinical aspects of the project and analysis. A.R.S., D.F.L., and P.V.G. performed database curation. D.F.L., J.S., I.P., F.D., P.A.H., A.S.W. and P.V.G. designed the analytical strategy and analyzed the data. D.B.M. oversaw the Affymetrix 6.0 genotyping, and J.D., Y.Z., A.R.S, and P.V.G. performed the preparative genotyping and experimental work. J.R.O. contributed to interpretation of data in the MHC/HLA region, and K.S.K. contributed to the approach to clinical data. P.V.G. coordinated the overall study. All authors contributed to the current version of the paper.

Author Information Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints. Data have been deposited at dbGaP (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=gap), and the NIMH Center for Collaborative Genetic Studies on Mental Disorders (www.nimhgenetics.org). F.A. has received funds from Pfizer, Organon, and the Foundation for NIH. D.W.B. has received research support from Shire and Forest, has been on the speakers bureau for Pfizer, and has received consulting honoraria from Forest and Jazz. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Tandon R, Keshavan MS, Nasrallah HA. Schizophrenia, "just the facts"what we know in 2008. 2. Epidemiology and etiology. Schizophr Res. 2008;102:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cook EH, Jr, Scherer SW. Copy-number variations associated with neuropsychiatric conditions. Nature. 2008;455:919–923. doi: 10.1038/nature07458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnold SE, Talbot K, Hahn CG. Neurodevelopment, neuroplasticity, and new genes for schizophrenia. Progress in brain research. 2005;147:319–345. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(04)47023-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manolio TA, Brooks LD, Collins FS. A HapMap harvest of insights into the genetics of common disease. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1590–1605. doi: 10.1172/JCI34772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adegbola A, Gao H, Sommer S, Browning M. A novel mutation in JARID1C/SMCX in a patient with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A:505–511. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costa E, et al. Reviewing the role of DNA (cytosine-5) methyltransferase overexpression in the cortical GABAergic dysfunction associated with psychosis vulnerability. Epigenetics. 2007;2:29–36. doi: 10.4161/epi.2.1.4063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawasaki H, Iwamuro S. Potential roles of histones in host defense as antimicrobial agents. Infectious disorders drug targets. 2008;8:195–205. doi: 10.2174/1871526510808030195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malcherek G, et al. The B7 homolog butyrophilin BTN2A1 is a novel ligand for DC-SIGN. J Immunol. 2007;179:3804–3811. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oksenberg JR, Baranzini SE, Sawcer S, Hauser SL. The genetics of multiple sclerosis: SNPs to pathways to pathogenesis. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:516–526. doi: 10.1038/nrg2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Purcell S, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang L, et al. Genotype-imputation accuracy across worldwide human populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:235–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wassink TH, et al. Evaluation of the chromosome 2q37.3 gene CENTG2 as an autism susceptibility gene. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005;136B:36–44. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.