Abstract

Background

Heart failure (HF) developing in hypertensive patients may occur with preserved or reduced left ventricular ejection fraction [PEF (≥50%) or REF (<50%)]. In the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT), 42,418 high-risk hypertensive patients were randomized to chlorthalidone, amlodipine, lisinopril, or doxazosin, providing an opportunity to compare these treatments with regard to occurrence of hospitalized HFPEF or HFREF.

Methods and Results

HF diagnostic criteria were pre-specified in the ALLHAT protocol. EF estimated by contrast ventriculography, echocardiography or radionuclide study was available in 910 (66.6%) of 1367 patients with hospitalized events meeting ALLHAT criteria. Cox regression models adjusted for baseline characteristics were used to examine treatment differences for HF (overall and by PEF and REF). HF case-fatality rates were examined. Of those with EF data, 44.4% had HFPEF and 55.6% had HFREF. Chlorthalidone reduced the risk of HFPEF compared with amlodipine, lisinopril, or doxazosin; the hazard ratios [HRs] and 95% CIs were 0.69 (0.53-0.91; p=0.009), 0.74 (0.56-0.97; p=0.032), and 0.53 (0.38-0.73; p<0.001), respectively. Chlorthalidone reduced the risk of HFREF compared with amlodipine or doxazosin; HRs were 0.74 (0.59-0.94; p=0.013) and 0.61 (0.47-0.79; p<0.001), respectively. Chlorthalidone was similar to lisinopril with regard to incidence of HFREF; HR=1.07 (0.82-1.40; p=0.596). Following HF onset, death occurred in 29.2% of participants (chlorthalidone/amlodipine/lisinopril) with new-onset HFPEF versus 41.9% in those with HFREF, p<0.001 (median follow-up 1.74 years); and in the terminated early chlorthalidone/doxazosin comparison 20.0% (HFPEF) versus 26.0% (HFREF), p=0.185 (median follow-up 1.55 years).

Conclusions

In the ALLHAT trial, using adjudicated outcomes, chlorthalidone significantly reduced the occurrence of new-onset hospitalized HFPEF and HFREF compared with amlodipine and doxazosin. Chlorthalidone also reduced the incidence of new-onset HFPEF compared with lisinopril. Among high-risk hypertensive men and women, HFPEF has a better prognosis than HFREF.

Keywords: antihypertensive therapy; hypertension, detection and control; diuretics; angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; calcium channel blockers; heart failure; ejection fraction

The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) was a randomized double-blind, multicenter clinical trial designed to determine whether treatment initiated with a calcium channel blocker (amlodipine), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (lisinopril), or an α-adrenergic blocker (doxazosin), would reduce the incidence of fatal coronary heart disease (CHD) or nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) more than treatment with a thiazide-type diuretic (chlorthalidone) in high-risk patients with hypertension aged 55 years or older. Secondary outcomes were all-cause mortality and major cardiovascular disease events including heart failure (HF).1 Compared with chlorthalidone, new onset HF occurred more frequently in patients randomized to amlodipine, lisinopril, and doxazosin-based strategies with significant hazard ratios of 1.38, 1.19, and 1.80, respectively.2,3 Toaddress concerns about the ALLHAT HF diagnosis4-5, the Heart Failure Validation Study (HFVS) was designed to adjudicate all hospitalized HF events in a centrally blinded manner.6

Among the data collected in the HFVS were measurements of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) reported in hospitalization records. Patients with reduced LVEF (REF) have primarily systolic dysfunction and those with preserved LVEF (PEF), primarily diastolic dysfunction. Both presentations are common in hypertensive patients and both experience high mortality and morbidity rates.7-18 Importantly, because HFPEF patients have generally been excluded from large clinical trials, little is known about the relative efficacy of commonly used antihypertensive medications in preventing these outcomes.19-21 The purpose of this paper is to examine the incidence of HFPEF and HFREF in hospitalized HF patients by treatment assignment in ALLHAT and determine whether differences exist in their subsequent survival.

Methods

ALLHAT was sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Its design and rationale have been published.1 Men and women, aged 55 years and older with hypertension and one additional risk factor for CHD were included. Persons with history of treated symptomatic HF or history of hospitalization for HF or known LVEF lower than 35% were excluded. However, measurement of LVEF was not dictated by the ALLHAT protocol. Participants were randomly assigned to step 1 drugs of chlorthalidone, amlodipine, lisinopril, or doxazosin in a ratio of 1.7:1:1:1. All collaborating ALLHAT clinical centers obtained institutional review approval and participants gave written informed consent. Follow-up visits were at one month, three, six, nine, and 12 months and every four months thereafter up to a range of possible follow-up of 3 years, 8 months to 8 years, one month. Patients were treated in a double-blind fashion to achieve a goal blood pressure (BP) of less than 140/90 mm Hg by titrating the step 1 randomized drug and adding step 2 (atenolol, clonidine or reserpine) or step 3 (hydralazine) open-label agents supplied by the study as clinically indicated.

The primary outcome was fatal CHD or nonfatal MI; major prespecified secondary outcomes were all-cause mortality, fatal and nonfatal stroke, combined CHD (primary outcome, coronary revascularization or hospitalized angina) and combined cardiovascular disease (combined CHD; stroke; other treated angina; fatal, hospitalized or treated non-hospitalized HF; or peripheral arterial disease). Study outcomes were assessed by the clinical centers at follow-up visits and hospitalized or fatal outcomes were based on clinic reports supported by discharge summaries and/or death certificates.

In the HFVS, relevant hospital records were obtained for all hospitalized HF events that occurred between February 1, 1994 and March 31, 2002 (February 15, 2000 for the doxazosin/chlorthalidone comparison). The records were abstracted by cardiology fellows blinded to treatment assignment. Six algorithmic approaches based on ALLHAT and Framingham criteria were assigned by computer. In addition, the reviewers rendered their independent clinical judgment on whether the patient had HF.6 This paper is based on the ALLHAT definition of one sign (rales, ankle edema>2+, tachycardia>120/min, cardiomegaly by chest x-ray, chest x-ray characteristic of HF, S3 gallop, jugular venous distention) and one concurrent symptom (paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea, or dyspnea at rest or ordinary exertion). Plans for analyses of outcomes by LVEF were prespecified in the HFVS protocol. Heart failure cases were classified into those with LVEF≥50% (HFPEF) and those with LVEF<50% (HFREF).

Among the 42,418 ALLHAT participants, 1,367 (70.6% of the 1,935 participants evaluated in the HFVS) had hospitalized HF events validated by ALLHAT criteria.6 Of these, LVEF assessment was available in 910 (66.6%). The source of LVEF was: cardiac catheterization report in 77 (8.5%), echocardiography study in 785 (86.5%) and radionuclide study in 48 (5.3%). Actual numerical values were available for 709 (77.9%) events. For the other 201, lab ranges based on the categories of normal, borderline, and impaired were available to accurately assign LVEFs of <50% or ≥50%. The analyses comparing HFPEF with HFREF presented in this paper are based on these 910 participants with one or more HF events. The authors had full access to the data and take responsibility for its integrity. All authors have read and agree to the manuscript as written.

Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics were compared across three HF groups (HFPEF, HFREF, no EF data) using the Z-test for continuous covariates and chi-square analysis for categorical data. Multivariate Cox regression models were employed to examine differences in risk of the three HF outcomes across randomized treatment comparisons, unadjusted and while controlling for age, race, gender, prior treatment for hypertension, systolic BP (SBP), diastolic BP (DBP), heart rate, current smoking, type II diabetes, left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) by clinic-reported electrocardiogram (ECG), evidence of CHD, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), body mass index (BMI), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL). Participants were censored at the time of death, development of another type of HF, or loss to follow-up. For example, if HF with no LVEF data was the outcome, an individual who developed HFREF first was censored at that time. In addition, multinomial multivariate logistic models were used to examine treatment differences.22 Cumulative event rates were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Case-fatality rates for HF were also examined using Kaplan-Meier curves and Cox regression. These mortality analyses start at the time of the HF diagnosis. Additionally, post-HF mortality risk was obtained using multivariate Cox regression with the HF event as a time-dependent variable. A p-value <0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance for the results. However, given the many analyses performed, statistical significance at this level should be interpreted with caution.

Results

Characteristics of participants with HFPEF and HFREF

Among 910 HF cases with LVEF assessment, HFPEF was present in 404 (44%) cases and HFREF was present in the remaining 506 (56%) cases. There were 148/709 cases (20.9%) with LVEF between 40% and 49%; 274/709 cases (38.6%) with LVEF<40%; and 150/709 cases (21.2%) with LVEF<30%.

Baseline characteristics of participants with hospitalized HFPEF and HFREF are shown in Table 1. Participants with HFPEF versus those with HFREF were more likely to be women (51.5% versus 37.7%, p<0.001) and less likely to have a history of CHD (32.1% versus 39.0%, p=0.03). Also, those with HFPEF had a higher mean BMI (31.9 versus 29.9, p<0.001), a higher mean HDL cholesterol (1.2 versus 1.1 mmol/L (45.2 versus 42.5 mg/dL, p<0.01), and tended to have higher mean SBP (149.6 versus 147.8 mmHg, p=0.09. In the general ALLHAT population, 46.8% of participants were women, 25.6% had a history of CHD, mean BMI was 29.7, mean HDL cholesterol was 1.2 mmol/L, and mean SBP was 146.3 mmHg. There were no statistically significant differences between these LVEF groups in age, race, diabetic status, LVH by clinic-reported or by centrally Minnesota coded-ECG, lipid values, potassium, glucose, eGFR, or assignment to statins. When these characteristics were examined by assigned therapy (data not shown), the patterns noted above were essentially similar.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Ejection Fraction

| Baseline Characteristics n (%) | Preserved (PEF) (EF ≥50%) (n=404) | Reduced (REF) (EF <50%) (n=506) | No EF Data (n=457) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEF vs. REF | PEF vs. No EF | REF vs. No EF | ||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 69.6 (8.1) | 69.7 (7.8) | 69.8 (7.8) | 0.90 | 0.78 | 0.87 |

| 55-64 years | 119 (29.5) | 134 (26.5) | 126 (27.6) | 0.32 | 0.54 | 0.70 |

| ≥65 years | 285 (70.5) | 372 (73.5) | 331 (72.4) | |||

| Race White | 259 (64.1) | 311 (61.5) | 247 (54.0) | 0.91 | 0.05 | 0.13 |

| Black | 132 (32.7) | 174 (34.4) | 195 (42.7) | |||

| Other | 13 ( 3.2) | 21 ( 4.2) | 15 ( 3.3) | |||

| Women | 208 (51.5) | 191 (37.7) | 196 (42.9) | <0.001 | 0.01 | 0.10 |

| Current Smoker | 78 (19.3) | 93 (18.4) | 85 (18.6) | 0.72 | 0.79 | 0.93 |

| Treated (antihypertensive) | 383 (94.8) | 470 (92.9) | 427 (93.4) | 0.24 | 0.40 | 0.74 |

| ASCVD* | 246 (60.9) | 329 (65.0) | 307 (67.2) | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.48 |

| History of CHD† | 129 (32.1) | 196 (39.0) | 184 (40.8) | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.58 |

| Type ∥ Diabetes | 204 (50.5) | 255 (50.4) | 246 (53.8) | 0.98 | 0.33 | 0.29 |

| LVH‡ by ECG | 77 (19.1) | 102 (20.2) | 86 (18.8) | 0.68 | 0.93 | 0.60 |

| LVH‡ by Echocardiogram | 27 (6.7) | 25 (4.9) | 23 (5.0) | 0.26 | 0.30 | 0.95 |

| LVH‡ by ECG/Minnesota Code | 33 (8.2) | 53 (10.5) | 52 (13.0) | 0.24 | 0.13 | 0.72 |

| Blood Pressure, in mmHg | ||||||

| SBP, mean (SD) | 149.6 (16.4) | 147.8 (16.3) | 148.8 (16.0) | 0.09 | 0.47 | 0.32 |

| DBP, mean (SD) | 80.6 (10.4) | 81.5 (11.2) | 82.5 (10.8) | 0.22 | <0.01 | 0.19 |

| Treated | ||||||

| SBP, mean (SD) | 149.0 (16.4) | 146.7 (16.1) | 148.0 (16.0) | 0.04 | 0.39 | 0.23 |

| DBP, mean (SD) | 80.5 (10.4) | 81.1 (11.1) | 81.8 (10.6) | 0.44 | 0.08 | 0.32 |

| Untreated | ||||||

| SBP, mean (SD) | 160.7 (12.5) | 161.4 (12.2) | 160.0 (10.7) | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.64 |

| DBP, mean (SD) | 82.4 (10.0) | 86.8 (11.7) | 91.3 (10.8) | 0.15 | <0.01 | 0.11 |

| Body Mass Index, mean (SD) | 31.9 (7.5) | 29.9 (6.4) | 30.6 (7.1) | <0.001 | <0.01 | 0.10 |

| Fasting Glucose§ | ||||||

| mean (SD) | 7.8 (3.8) | 8.0 (3.8) | 8.0 (4.1) | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.95 |

| ≥6.993§ | 117 (40.5) | 188 (46.8) | 145 (43.8) | 0.09 | 0.38 | 0.42 |

| Estimated GFR∥, mean (SD) | 72.0 (19.6) | 72.4 (21.7) | 72.2 (21.7) | 0.79 | 0.89 | 0.90 |

| LDL§, mean (SD) | 3.4 (1.0) | 3.6 (1.1) | 3.6 (1.0) | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.33 |

| HDL§ mean (SD) | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.1 (0.3) | 1.2 (0.4) | <0.01 | 0.87 | 0.02 |

| <0.9065§ | 86 (22.8) | 136 (28.2) | 105 (24.5) | 0.07 | 0.57 | 0.21 |

| Triglyceride§, mean (SD) | 2.1 (1.5) | 2.1 (1.6) | 2.1 (1.5) | 0.63 | 0.61 | 0.97 |

| Assigned to Pravastatin (LLT) | 40 (9.9) | 61 (12.1) | 45 (9.8) | 0.33 | 0.96 | 0.34 |

History of MI or stroke, history of coronary revascularization, major ST segment depression or T-wave inversion on any electrocardiogram (ECG) in the past 2 years, other atherosclerotic CVD (history of angina pectoris; history of intermittent claudication, gangrene, or ischemic ulcers; history of transient ischemic attack; coronary, peripheral vascular, or carotid stenosis ≥50% documented by angiography or Doppler studies; ischemic heart disease documented by reversible or fixed ischemia on stress thalium or dypyridamole thalium, ST depression ≥1 mm for ≥1 minute on exercise testing or Holter monitoring; reversible wall motion abnormality on stress echocardiogram; ankle-arm index <0.9; abdominal aortic aneurysm detected by ultrasonography, computed tomography scan or radiograph; carotid or femoral bruits)

Six subjects are missing CHD data (PEF:2; REF:4)

Left ventricular hypertrophy - ascertained from ECG or Echo by checkbox on enrollment form, Minnesota code as measured by ALLHAT on BL ECG

mmol/L

Glomerular Filtration Rate, mL/min per 1.73 m2

Symptoms and signs in participants with HFPEF and HFREF

The symptoms and signs of HF were similar in the two groups of participants. However, participants with HFPEF compared to those with HFREF were more likely to have bilateral ankle edema (66.6% versus 54.2%, p<0.001) or ankle edema 2+ (38.1% versus 26.1%, p<0.001). They were less likely to have paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea (29.0% compared with 35.4%, p=0.04), S3 gallop (9.7% versus 19.8%, p<0.001), hepatomegaly, (2.2% versus 5.9%, p=0.006) and pulmonary vascular redistribution (16.1% versus 22.3%, p=0.02).

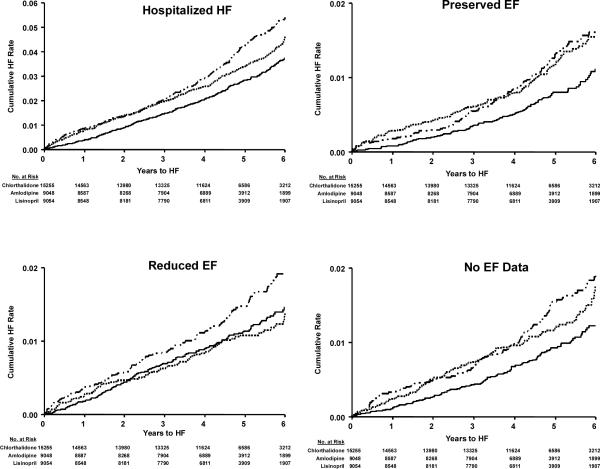

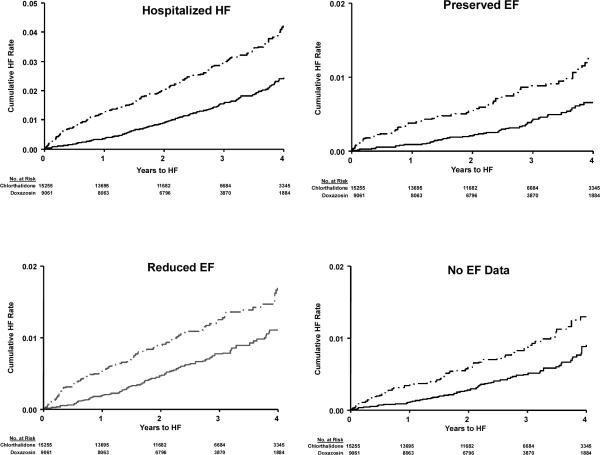

Treatment Effects in Participants with HFPEF and HFREF

Cox regression models were used to examine relative treatment effects for patients with HFPEF, HFREF or HF with no EF data available versus patients with no HF (Table 2, Figures 1a and 1b), unadjusted and adjusted for baseline characteristics of age, race, gender, prior hypertension treatment, SBP, DBP, heart rate, smoking, diabetes, LVH by reported ECG, history of CHD, eGFR, BMI, and HDL. Those with no EF data available showed similar results to those with HFPEF. Chlorthalidone significantly reduced risk of 1) overall hospitalized HF, 2) HFPEF, and 3) HF in patients with no EF data available compared with amlodipine, lisinopril, and doxazosin. Chlorthalidone also significantly reduced HFREF risk compared with amlodipine and doxazosin, but had a similar effect as lisinopril. Multinomial logistic regression analyses were also performed and showed similar results (data not shown).

Table 2.

Treatment Comparisons for Validated Heart Failure (HF) Outcomes*

| Chlorthalidone | Chlorthalidone | Chlorthalidone | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | vs Amlodipine | p | vs Lisinopril | p | vs Doxazosin | p |

| Univariate Cox Proportional Hazard Regression HR (95% Confidence Intervals) | ||||||

| Hospitalized† | 0.68 (0.59-0.79) | >0.001 | 0.84 (0.72-0.97) | 0.021 | 0.55 (0.46-0.65) | >0.001 |

| Preserved EF (PEF) ‡ | 0.63 (0.49-0.82) | 0.001 | 0.70 (0.54-0.92) | 0.010 | 0.52 (0.37-0.71) | >0.001 |

| Reduced EF (REF)§ | 0.78 (0.62-0.98) | 0.032 | 1.10 (0.86-1.42) | 0.440 | 0.64 (0.49-0.82) | 0.001 |

| No EF Data∥ | 0.63 (0.49-0.80) | >0.001 | 0.74 (0.57-0.95) | 0.020 | 0.60 (0.45-0.81) | 0.001 |

| Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazard Regression HR (95% Confidence Intervals) | ||||||

| Hospitalized HF† | 0.67 (0.58-0.78) | >0.001 | 0.84 (0.72-0.98) | 0.023 | 0.53 (0.44-0.63) | >0.001 |

| Preserved EF (PEF)‡ | 0.69 (0.53-0.91) | 0.009 | 0.74 (0.56-0.97) | 0.032 | 0.53 (0.38-0.73) | >0.001 |

| Reduced EF (REF)§ | 0.74 (0.59-0.94) | 0.013 | 1.07 (0.82-1.40) | 0.596 | 0.61 (0.47-0.79) | >0.001 |

| No EF Data∥ | 0.59 (0.46-0.76) | >0.001 | 0.72 (0.55-0.94) | 0.015 | 0.56 (0.41-0.77) | >0.001 |

Multivariate models adjusted for the following baseline characteristics: age, race, gender, treatment for hypertension, SBP, DBP, heart rate, current smoking, type II diabetes, LVH by reported ECG, presence of CHD, eGFR, BMI, and HDL.

Chlorthalidone/Amlodipine/Lisinopril/Doxazosin # of events

n=426/369/298/274;

n=117/110/98/79;

n=173/131/92/110;

n=136/128/108/85

Figure 1.a.

Validated Hospitalized HF; Validated HF by Preserved EF, Reduced EF, and No EF Data Categories by Treatment Group (Chlorthalidone/Amlodipine/Lisinopril)

Figure 1b.

Validated Hospitalized HF; Validated HF by Preserved EF, Reduced EF, and No EF Data Categories by Treatment Group (Chlorthalidone/Doxazosin)

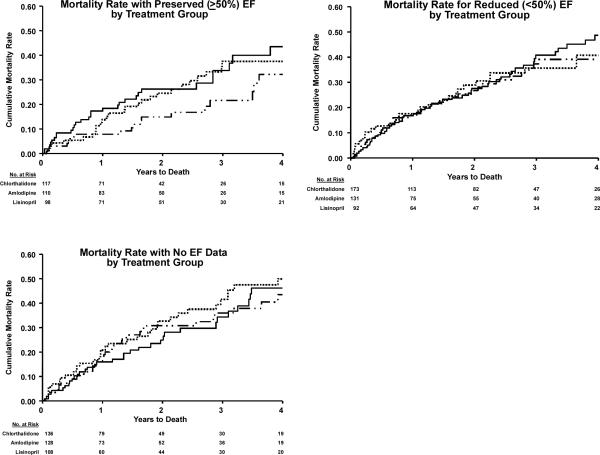

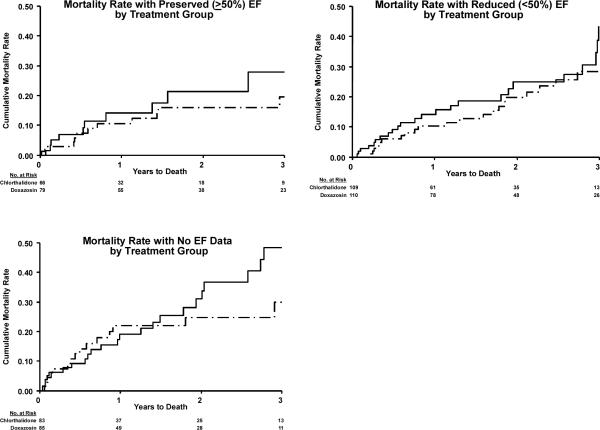

Prognosis of Participants with HFPEF and HFREF

Lower mortality was associated with HFPEF compared with HFREF during the remainder of the ALLHAT follow-up, with median times of 1.74 (chlorthalidone/amlodipine/lisinopril) and 1.55 years (chlorthalidone/doxazosin). Following first HF hospitalization with HFPEF in the chlorthalidone/amlodipine/lisinopril comparison, 29.2% of participants died compared with 41.9% of those with HFREF (p<0.001). In the chlorthalidone/doxazosin comparison, these rates were 20.0% (HFPEF) and 26.0% (HFREF), p=0.185, (Table 3, Figure 2a and 2b). Among those with data available on the visit post-HF, 51.6% (174/337) of HFPEF patients, 59.7% (249/417) of HFREF patients, and 47.9% (167/349) of HF with no EF data patients were on an ACE inhibitor or beta blocker. Also, at the visit post-HF, statin use was lower in HFREF (64.5%) than in the other HF groups (PEF=75.4% and no EF data=73.6%). The patterns of the occurrence of death among participants with either HFREF or HFPEF by randomized drug treatment were similar, and no differences in the occurrence of death after HF by randomized drug treatment were seen (Figure 2a and 2b). Using time-dependent Cox regression, the hazard ratios for mortality for participants who developed HFPEF, HFREF, and HF with no EF data versus those who did not develop HF were 4.17, 5.76, and 6.04, (all p<0.001), respectively.

Table 3.

Vital Status by Randomization Group and Ejection Fraction (EF)

| Vital Status, n (%) | Preserved (EF >50%) (n=404) | Reduced (EF <50%) (n=506) | P (REF vs. PEF) | No EF Data (n=457) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorthalidone HF Events | n=117 | n=173 | n=136 | |

| Deaths post-HF | 35 (29.9) | 72 (41.6) | 0.043 | 57 (41.9) |

| Amlodipine HF Events | n=110 | n=131 | n=128 | |

| Deaths post-HF | 25 (22.7) | 56 (42.7) | 0.001 | 51 (39.8) |

| Lisinopril HF Events | n=98 | n=92 | n=108 | |

| Deaths post-HF | 35 (35.7) | 38 (41.3) | 0.429 | 55 (50.9) |

| Total HF Events | n=325 | n=396 | n=372 | |

| Deaths post-HF | 95 (29.2) | 166 (41.9) | <0.001 | 163 (43.8) |

| February 15, 2000 Cut-Off | ||||

| Chlorthalidone HF Events | n=66 | n=109 | n=83 | |

| Deaths post-HF | 14 (21.2) | 33 (30.3) | 0.190 | 30 (36.1) |

| Doxazosin HF Events | n=79 | n=110 | n=85 | |

| Deaths post-HF | 15 (19.0) | 24 (21.8) | 0.635 | 26 (30.6) |

| Total HF Events | n=145 | n=219 | n=168 | |

| Deaths post-HF | 29 (20.0) | 57 (26.0) | 0.185 | 56 (33.3) |

Figure 2a.

Mortality after occurrence of validated HF with preserved EF (PEF) and reduced EF (REF) in ALLHAT. (Amlodipine/Lisinopril/Chlorthalidone comparison)

Figure 2b.

Mortality after occurrence of validated HF with preserved EF (PEF) and reduced EF (REF) in ALLHAT. (Doxazosin/Chlorthalidone comparison)

Discussion

Patients presenting with HF and PEF are heterogeneous.8, 14-15, 23-24 It is assumed that in most cases they have elevated left atrial pressures resulting in pulmonary congestion and dyspnea, but this may occur only transiently. The underlying pathophysiology usually includes loss of LV diastolic compliance due to LVH, interstitial abnormalities, or both. 25-33 In addition, impaired diastolic relaxation (an active energy-requiring process), increased vascular stiffness, increased intravascular volume, or volume redistribution may contribute.12, 28, 34-36 Chronic hypertension and cardiovascular changes associated with aging, often associated with renal impairment, are the most common causes. Valvular abnormalities, myocardial ischemia, restrictive cardiomyopathy, and pericardial disease may also present with this picture. 12-13,24, 37-38 In clinical practice, the focus is on the accurate diagnosis of HF, measurement of LVEF, and excluding alternative and reversible causes of this condition.39-40 At present, there is no proven therapy for this condition, and treatment is largely empirical, focusing on BP control and treating or avoiding intravascular volume overload.27, 41

As a result of its large number of patients and their prolonged prospective follow-up, the ALLHAT Heart Failure Validation Study has provided an unrivaled opportunity to observe and characterize the occurrence of this condition. Furthermore, since ALLHAT compared four different classes of initial antihypertensive drugs, it provides unique information concerning the relative efficacy of these agents in preventing the occurrence of HF overall and in patients with either HFPEF or HFREF.

The findings from ALLHAT demonstrate what has previously been observed in registries and observational studies of patients for decompensated HF, that in high-risk older treated hypertensives, HFPEF (when defined by an LVEF cutpoint of 50%) is somewhat less common than HFREF, that it occurs more frequently in women, and has lower initial mortality than that of HFREF, but it still has a poor long-term outcome. The low prevalence of ECG LVH by Minnesota code (11.7% overall) in those with HF outcomes seems at odds with other reports. In the Candesartan in Heart failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity (CHARM) trials,42 the prevalence was 15.7%; in the Framingham Heart Study, it was14% of those with REF and 22% of those with PEF;10 and in a study by Thomas et al.,39 it was 42% in those with REF and 22% in those with PEF. Measures of LVH at the time of HF in ALLHAT were not obtained, so the actual prevalence of LVH at the time of HF diagnosis is unknown.

The most important findings of this study relate to the observed differences in the occurrence of HF among the randomized treatment groups and their relationship to the associated LVEF presentation. Ejection fraction data have not been available for patients developing HF in most previous hypertension treatment trials, although it is likely, given the generally older age of these patients, that many had HFPEF. Trials that have demonstrated a reduction in HF with antihypertensive therapy have for the most part utilized diuretic-based therapies or inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system.41,43-45 In ALLHAT, chlorthalidone treatment was associated with a lower incidence of new-onset validated hospitalized HF than doxazosin, amlodipine, or lisinopril treatment. In patients with HFPEF, this difference was statistically significant versus all three comparators. In the group with HFREF, however, although chlorthalidone reduced the occurrence of HF relative to doxazosin and amlodipine, it was similar to lisinopril. These data suggest that there are differences in the pathophysiology of these presentations and confirm the observations of many HF trials that renin-angiotensin system inhibition effects go beyond BP-lowering in preventing HF in patients with REF.41,45 However, in ALLHAT a thiazide-type diuretic prevented HFREF as well as a renin-angiotensin system inhibitor.

Limitations of this analysis of ALLHAT data include 1) the evaluation of ventricular function was not dictated by the protocol, 2) only hospitalized HF events were evaluated, 3) assessment of LVEF was not available in a significant proportion of the patients, 4) lack of complete information on post-HF medication use, and 5) post-HF mortality analyses were based on post-randomization data. However, the large number of HF events analyzed and the double-blind analyses lend credence to the results.

In conclusion, HFPEF is common in treated patients with hypertension (compared to HFREF), HFPEF is associated with lower case fatality than HFREF, but the case-fatality rate is still high. Using validated outcomes, chlorthalidone significantly reduced the overall risk of HF and HF presenting with PEF compared with amlodipine, lisinopril or doxazosin. It also reduced the risk of HF presenting with REF compared with amlodipine and doxazosin. Chlorthalidone was similar to lisinopril in reducing HF presenting with REF. Based on the data from many HF trials, a combination of these last two agents would be expected to be particularly effective in preventing HF in this group.

A complete list of members of the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group has been published previously.3

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This research was supported by Health and Human Services contract number N01-HC-35130 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services, Bethesda, MD. The ALLHAT investigators acknowledge contributions of study medications supplied by Pfizer, Inc. (amlodipine), AstraZeneca (atenolol and lisinopril) and Bristol-Myers Squibb (pravastatin) and financial support provided by Pfizer, Inc.

Footnotes

Registration URL: www.clinicaltrials.gov Unique identifier: NCT00000542

Disclosures: HRB has consulted for Boehringer Ingleheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CV Therapeutics, Daichi Sankyo, Forest Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Intercure, MSD, Gilead, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, and Sanofi-Synthelabo; has received honoraria from Boehringer Ingleheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, and Pfizer; and has served as a DSMB Chair for Novartis. WCC has consulted for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Calpis, Forest Pharmaceuticals, King, Myogen, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sankyo, Sanofi-Aventis, Sanofi-Synthelabo, and Takeda; has received honoraria from Astra-Zeneca, Boehringer Ingleheim, Forest Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sankyo; and has received research grants from Abbott Laboratories, Astra-Zeneca, and Novartis. BRD has consulted for BioMarin, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Proctor and Gamble, and Takeda. MAF has ownership interest in Pfizer. CEF has consulted for BioMarin. JBK has consulted for Pfizer and Schering Plough; has received research grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, KOS, and Pfizer; and has received honoraria from Lilly/ICOS, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, and Schering Plough. BMM has consulted for Astra-Zeneca, Bayer Corporation, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novacardia, Novartis, Sanofi-Synthelabo, and Scios; has received research grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novacardia, and Sanofi-Synthelabo; and has received honoraria from Sanofi-Synthelabo. PTE, DL, SN, and LMS have no financial interests to disclose.

References

- 1.Davis BR, Cutler JA, Gordon DJ, Furberg CD, Wright JT, Jr, Cushman WC, Grimm RH, LaRosa J, Whelton PK, Perry HM, Alderman MH, Ford CE, Oparil S, Francis C, Proschan M, Pressel S, Black HR, Hawkins CM. Rationale and design for the Antihypertensive and Lipid Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). ALLHAT Research Group. Am J Hypertens. 1996;9:342–360. doi: 10.1016/0895-7061(96)00037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Major cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients randomized to doxazosin vs chlorthalidone: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial l (ALLHAT). ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. JAMA. 2000;283:1967–1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) JAMA. 2002;288:2981–2997. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.23.2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Messerli FH. Doxazosin and congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:1295–1296. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01534-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weber MA. The ALLHAT report: A case of information and misinformation. J Clin Hypertens. 2003;5:9–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2003.02287.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Einhorn PT, Davis BR, Massie BM, Cushman WC, Piller LB, Simpson LM, Levy D, Nwachuku CE, Black HR, ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group The Antihypertensive and Lipid Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) Heart Failure Validation Study: diagnosis and prognosis. Am Heart J. 2007 Jan;153(1):42–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kupari M, Lindroos M, Iivanainen AM, Heikkila J, Tilvis R. Congestive heart failure in old age: Prevalence, mechanisms and 4-year prognosis in the Helsinki Ageing Study. J Intern Med. 1997;241:387–394. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1997.129150000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Senni M, Tribouilloy CM, Rodeheffer RJ, Jacobsen SJ, Evans JM, Bailey KR, Redfield MM. Congestive heart failure in the community: A study of all incident cases in Olmsted County, Minnesota, in 1991. Circulation. 1998;98:2282–2289. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.21.2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vasan RS, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Prevalence, clinical features and prognosis of diastolic heart failure: An epidemiologic perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:1565–1574. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00381-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vasan RS, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Evans JC, Reiss CK, Levy D. Congestive heart failure in subjects with normal versus reduced left ventricular ejection fraction: Prevalence and mortality in a population-based cohort. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1948–1955. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00118-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mosterd A, Hoes AW, de Bruyne MC, Deckers JW, Linker DT, Hofman A, Grobbee DE. Prevalence of heart failure and left ventricular dysfunction in the general population; The Rotterdam Study. Eur Heart J. 1999;20:447–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitzman DW, Gardin JM, Gottdiener JS, Arnold A, Boineau R, Aurigemma G, Marino EK, Lyles M, Cushman M, Enright PL, Cardiovascular Health Study Research Group Importance of heart failure with preserved systolic function in patients > or = 65 years of age. CHS Research Group. cardiovascular health study. Am J Cardiol. 2001;87:413–419. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01393-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devereux RB, Roman MJ, Liu JE, Welty TK, Lee ET, Rodeheffer R, Fabsitz RR, Howard BV. Congestive heart failure despite normal left ventricular systolic function in a population-based sample: The Strong Heart Study. Am J Cardiol. 2000;86:1090–1096. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01165-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDermott MM, Feinglass J, Lee PI, Mehta S, Schmitt B, Lefevre F, Gheorghiade M. Systolic function, readmission rates, and survival among consecutively hospitalized patients with congestive heart failure. Am Heart J. 1997;134:728–736. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(97)70057-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peyster E, Norman J, Domanski M. Prevalence and predictors of heart failure with preserved systolic function: Community hospital admissions of a racially and gender diverse elderly population. J Card Fail. 2004;10:49–54. doi: 10.1016/s1071-9164(03)00579-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dauterman KW, Go AS, Rowell R, Gebretsadik T, Gettner S, Massie BM. Congestive heart failure with preserved systolic function in a statewide sample of community hospitals. J Card Fail. 2001;7:221–228. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2001.26896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith GL, Masoudi FA, Vaccarino V, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. Outcomes in heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction: Mortality, readmission, and functional decline. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1510–1518. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00185-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gottdiener JS, McClelland RL, Marshall R, Shemanski L, Furberg CD, Kitzman DW, Cushman M, Polak J, Gardin JM, Gersh BJ, Aurigemma GP, Manolio TA. Outcome of congestive heart failure in elderly persons: Influence of left ventricular systolic function. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:631–639. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-8-200210150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Redfield MM. Understanding “diastolic” heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1930–1931. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Konstam MA. “Systolic and diastolic dysfunction” in heart failure? Time for a new paradigm. J Card Fail. 2003;9:1–3. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2003.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL, Redfield MM. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:251–259. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. 2nd ed. Wiley; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jessup M, Brozena S. Heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2007–2018. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maurer MS, Burkhoff D, Fried LP, Gottdiener J, King DL, Kitzman DW. Ventricular structure and function in hypertensive participants with heart failure and a normal ejection fraction: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:972–981. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grossman W. Diastolic dysfunction and congestive heart failure. Circulation. 1990;81:III1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kitzman DW, Little WC, Brubaker PH, Anderson RT, Hundley WG, Marburger CT, Brosnihan B, Morgan TM, Stewart KP. Pathophysiological characterization of isolated diastolic heart failure in comparison to systolic heart failure. JAMA. 2002;288:2144–2150. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.17.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aurigemma GP, Gaasch WH. Clinical practice. Diastolic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1097–1105. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp022709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zile MR, Baicu CF, Gaasch WH. Diastolic heart failure--abnormalities in active relaxation and passive stiffness of the left ventricle. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1953–1959. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baicu CF, Zile MR, Aurigemma GP, Gaasch WH. Left ventricular systolic performance, function, and contractility in patients with diastolic heart failure. Circulation. 2005;111:2306–2312. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000164273.57823.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borbely A, van der Velden J, Papp Z, Bronzwaer JG, Edes I, Stienen GJ, Paulus WJ. Cardiomyocyte stiffness in diastolic heart failure. Circulation. 2005;111:774–781. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000155257.33485.6D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Heerebeek L, Borbely A, Niessen HW, Bronzwaer JG, van der Velden J, Stienen GJ, Linke WA, Laarman GJ, Paulus WJ. Myocardial structure and function differ in systolic and diastolic heart failure. Circulation. 2006;113:1966–1973. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.587519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lam CS, Roger VL, Rodeheffer RJ, Bursi F, Borlaug BA, Ommen SR, Kass DA, Redfield MM. Cardiac structure and ventricular-vascular function in persons with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction from Olmsted County, Minnesota. Circulation. 2007;115:1982–1990. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.659763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Melenovsky V, Borlaug BA, Rosen B, Hay I, Ferruci L, Morell CH, Lakatta EG, Najjar SS, Kass DA. Cardiovascular features of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction versus nonfailing hypertensive left ventricular hypertrophy in the urban Baltimore community: the role of atrial remodeling/dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:198–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zile MR, Brutsaert DL. New concepts in diastolic dysfunction and diastolic heart failure: Part II: causal mechanisms and treatment. Circulation. 2002;105:1503–1508. doi: 10.1161/hc1202.105290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gandhi SK, Powers JC, Nomeir AM, Fowle K, Kitzman DW, Rankin KM, Little WC. The pathogenesis of acute pulmonary edema associated with hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:17–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101043440103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maurer MS, King DL, El-Khoury Rumbarger L, Packer M, Burkhoff D. Left heart failure with a normal ejection fraction: identification of different pathophysiologic mechanisms. J Card Fail. 2005;11:177–187. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Topol EJ, Traill TA, Fortuin NJ. Hypertensive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy of the elderly. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:277–283. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501313120504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen HH, Lainchbury JG, Senni M, Bailey KR, Redfield MM. Diastolic heart failure in the community: Clinical profile, natural history, therapy, and impact of proposed diagnostic criteria. J Card Fail. 2002;8:279–287. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2002.128871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas JT, Kelly RF, Thomas SJ, Stamos TD, Albasha K, Parrillo JE, Calvin JE. Utility of history, physical examination, electrocardiogram, and chest radiograph for differentiating normal from decreased systolic function in patients with heart failure. Am J Med. 2002;112:437–445. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zile MR, Brutsaert DL. New concepts in diastolic dysfunction and diastolic heart failure: Part I: diagnosis, prognosis, and measurements of diastolic function. Circulation. 2002;105:1387–1393. doi: 10.1161/hc1102.105289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaye DM, Krum H. Drug discovery for heart failure: a new era or the end of the pipeline? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:127–139. doi: 10.1038/nrd2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hawkins NM, Wang D, McMurray JJV, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, Granger CB, Yusuf S, Pocock SJ, Ostergren J, Michelson EL, Dunn FG, the CHARM Investigators and Committees Prevalence and prognostic implications of electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy in heart failure: evidence from the CHARM programme. Heart. 2007;93:59–64. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.083949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kostis JB, Davis BR, Cutler J, Grimm RH, Jr, Berge KG, Cohen JD, Lacy CR, Perry HM, Jr, Blaufox MD, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Black HR, Schron E, Berkson DM, Curb JD, Smith WM, McDonald R, Applegate WB. Prevention of heart failure by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. SHEP Cooperative Research Group. JAMA. 1997;278:212–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kitzman DW. Therapy for diastolic heart failure: on the road from myths to multicenter trials. J Card Fail. 2001;7:229–231. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2001.27665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Asselbergs FW, van Gilst WH. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition in cardiovascular risk populations: a practical approach to identify the patient who will benefit most. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2007;22:267–272. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e3281a7ec81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]