Abstract

Differences between isogenic mouse strains in cellular expression of the neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit alpha4 (nAChRα4) by the dorsal hippocampus are well known. To investigate further the genetic basis of these variations, expression of the nAChRα4 subunit was measured in congenic mouse lines derived from two strains exhibiting notable divergence in the expression of this subunit: C3H and C57BL/6. Congenic lines carrying reciprocally introgressed regions (quantitative trait loci; QTL) from chromosomes 4, 5, and 12 each retained the phenotype most closely associated with the parental strain. However, in congenic lines harboring the reciprocal transfer of a chromosome 11 QTL, a characteristic difference in the ratio of interneurons versus astrocytes expressing nAChRα4 in the CA1 region is reversed relative to the parental strain. These finding suggest that this chromosomal segment harbors genes that regulate strain distinct hippocampal morphology that is revealed by nAChRα4 expression.

Keywords: Nicotinic receptors, mouse strains, interneurons, hippocampus, congenic analysis

INTRODUCTION

The susceptibility to the effects of nicotine is well-established as a behavioral characteristic of mice that also exhibits complex genetic (Crawley et al., 1997; Marks et al., 1989) and morphological variation (e.g., (Gahring et al., 2004a; Gahring et al., 2004b; Gahring et al., 2005). Further, genetic determinants of hippocampus morphology appear to impart a significant contribution to strain-specific differences in nAChR expression and very probably the measured differences in response to nicotine (Crawley et al., 1997; Marks et al., 1989). The morphology of this limbic structure is well defined, and it can exhibit substantial variability among isogenic mouse strains (Jucker et al., 2000; Lu et al., 2001; Peirce et al., 2003; Wimer et al., 1976). There is now evidence that within these strain dependent difference in hippocampal morphology, there are also differences in nicotinic receptor expression. For example, the Collins group (Crawley et al., 1997; Marks et al., 1989) recognized that different mouse strains exhibit often highly variable, yet strain dependent, differences in their physiological and behavioral response to nicotine administration. Of particular interest was that many of these differences could be quantitated to corresponded to strain-specific variations in the expression of high affinity nicotine binding sites or binding to brain tissue of alpha-bungarotoxin (Crawley et al., 1997; Marks et al., 1989). Also, in terms of behavior variations in functions regulated by the hippocampus were noted in terms of the response by different strains to nicotine. Subsequent analyses by this group and others (Crawley et al., 1997) have indicated that at least 8 genes control the phenotypes being measured. Evidence that some of these genes are likely to be structural subunits of the nAChR family has also been forthcoming. Adams and colleagues (Adams et al., 2001) used of congenic mouse development between the C3H and DBA2 mouse strains, that differences between these strains in the hippocampal expression of the alpha-bungarotoxin binding nicotinic receptor, nAChRα7 (Hogg et al., 2003) segregate with the nAChRα7 locus on chromosome 7. Similarly, polymorphisms altering the function and expression of nAChRα4 have been suggested to be related to strain-related differences in the influence of nicotine on several phenotypes (Dobelis et al., 2002).

Not all strain-related effects in nicotine response correspond with known variants of nAChRs (e.g. see Picciotto et al., 2001; Lester et al., 2003). We found that the expression of nAChR differs among inbred mouse strains based upon their unique morphology of the dorsal hippocampus (Gahring et al., 2004a; Gahring et al., 2004b; Gahring et al., 2005). This is particularly the case in the adult CA1 subregion for the expression of nAChRα4, which is a key component of the high affinity nicotine binding site (which also includes nAChRβ2; Hogg et al., 2003) and an important contributor to physiological responses to nicotine that lead to addiction (Lester et al., 2003). In our studies the expression of nAChRα4 by inhibitory interneurons and astrocytes (cell types defined by co-expression of nAChRα4 in cells positive for glutamic acid dehydrogenase (GAD) or glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP), respectively) in the CA1 region of the hippocampus varied inversely among inbred strains (Gahring et al., 2004a; Gahring et al., 2004b, Gahring et al., 2005; Gahring and Rogers, 2008). In the same studies, no staining for this subunit was detected in other cells present in this hippocampus such as microglia or endothelial cells. Two strains that exhibit the greatest difference in this interneuron:astrocyte phenotype are C3H and C57BL/6 where the expression of nAChRs by CA1 interneurons of C3H mice outnumbered astrocyte expression by approximately 3:1 while these values are reversed in C57BL/6 (B6) mice (Gahring et al., 2004a; Gahring and Rogers, 2008). Therefore, because nAChR expression differs in defined ways among these isogenic strains, the opportunity to identifying underlying genetic components contributing to these phenotypes is suggested.

To identify the genetic component(s) of mouse strain-specific hippocampal morphology and nAChR expression, we have examined nAChRα4 immunostaining in the dorsal CA1 hippocampus of several C3H×C57BL/6 reciprocal congenic mouse lines. For this study portions of chromosomes 4, 5, 11 and 12 were introgressed reciprocally from donor strain into the receiving strain background. In one of these congenic lines, termed Bb4, the reciprocal exchange of a portion of chromosome 11 (14 to 62 cM) reversed the interneuron:astrocyte nAChR immunostaining pattern relative to host strain background. Of note is that neither gene encoding the principal subunits of the high-affinity nicotine binding site (i.e., nAChRα4 or nAChRβ2) reside on this chromosome, nor do other members of the neuronal nicotinic receptor subunit family. Consequently, this finding supports the conclusion that genetic determinants of the measured differences in nAChR expression in CA1 reside on chromosome 11.

METHODS

Animals, congenic strain construction and nomenclature

For congenic strain construction, six distinct QTLs on five chromosomes that were originally identified as regulating the severity of murine Lyme arthritis were intercrossed between populations C3H and B6 mice (Roper et al., 2001). Congenic lines, in which donor alleles from one strain were introgressed into the reciprocal mouse strain, were generated and they are described with standard nomenclature. For example, C3.B6-Bb2Bb3 designates the C3H mouse carrying the Bb2Bb3 allele from the B6 strain. Four of these congenic lines coincide with changes in gene expression identified in this study. C3.B6-Bb2Bb3 and B6.C3-Bb2Bb3 congenic mouse lines carrying the region of chromosome 5 spanning Bb2 and Bb3 (D5Mit355 – D5Mit292; 26.2 cM – 73.2 cM) were generated by backcrossing seven generations beginning with BXH (C57BL/6×C3H/He) recombinant inbred lines 4 or 6 from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). C3.B6-Bb1 (D4Mit149-D4Mit190; 0 cM – 75.4 cM), B6.C3-Bb1 (D4Mit264-D4Mit145; 3.3 cM – 39.3), C3.B6-Bb4 (D11Mit229-D11Mit199; 10.9 cM – 63.4 cM), B6.C3-Bb4 (DD11Mit227-D11Mit199; 4.4 cM – 63.4 cM), and C3.B6-Bb6 (D12Mit201-D12Mit134; 23 cM – 57.9 cM), B6.C3-Bb6 (D12Mit5-D12Mit133; 31.7 cM – 52.5 cM) were generated by backcrossing seven generations onto C57BL/6NCr and C3H/HeNCr, starting with the (B6×C3H/HeN)F1. Microsatellite analyses with appropriate primers (Research Genetics) were used to identify mice carrying the region corresponding to each QTL and to eliminate known contaminating regions (Crandall et al., 2005; Roper et al., 2001). Congenic mouse lines homozygous for the introgressed Bb4 region were generated by filial mating, and confirmation of background purity was determined by total genome scan with 280 primer sets that discriminate between C3H and C57BL/6 genomic DNA in the University of Utah Core Sequencing Facility.

Immunohistochemistry

Primary antibodies to nAChRα4 (either rabbit polyclonal 5009 or 6964 or mouse monoclonal 4G10 (Gahring et al., 2004a; Rogers et al., 1998)) were used for these studies. As reported previously (Gahring et al., 2004a), both antibodies gave equivalent results. For immunohistochemistry, the methods have been described in detail previously (Rogers et al., 1998), adult (5–8 months) male mice were perfused transcardially first with saline to remove blood followed by a short perfusion with 0.2% paraformaldehyde+0.5% sucrose in phosphate buffer PBS before final perfusion with 2% paraformaldehyde+5% sucrose in PBS. The brains were removed, stored at 4°C in 2% paraformaldehyde+25% sucrose in PBS overnight before coronal sections (25 microns) were cut through the dorsal hippocampus on a sliding microtome. Sections were blocked (4% goat serum in PBS) before incubating in primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Sections were washed, incubated with the peroxidase coupled secondary antibody, washed and visualized. The stained free-floating sections were mounted on glass microscope slides and coverslipped for quantitative analysis (Rogers et al., 1998).

Data analysis

As before (Rogers et al., 1998; Gahring et al., 2004a; Gahring et al., 2005) at least 6 hippocampal sections in the coronal plane, matched to the equivalent dorsal aspect (between Bregma −1.7 to −2.2; Franklin and Paxinos, 2008) were collected at 125 micron intervals and digitally photographed using the meander-scan feature of the Neurolucida software package (MicroBrightField). The camera used was a DAGE 300 CCD camera attached to a Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope equipped with an automated stage (Ludl). Images were collected at with a Plan-Neofluar 10X or a 20X objective. Because astrocytes can be difficult to resolve with accuracy at lower magnifications, some image montages were generated using a Plan-Neofluar at 40X for confirmation of identity. Standard statistical tests used the GB-Stat v9.0 software package. Image assembly for presentation in the figures was done using Photoshop C2 software.

RESULTS

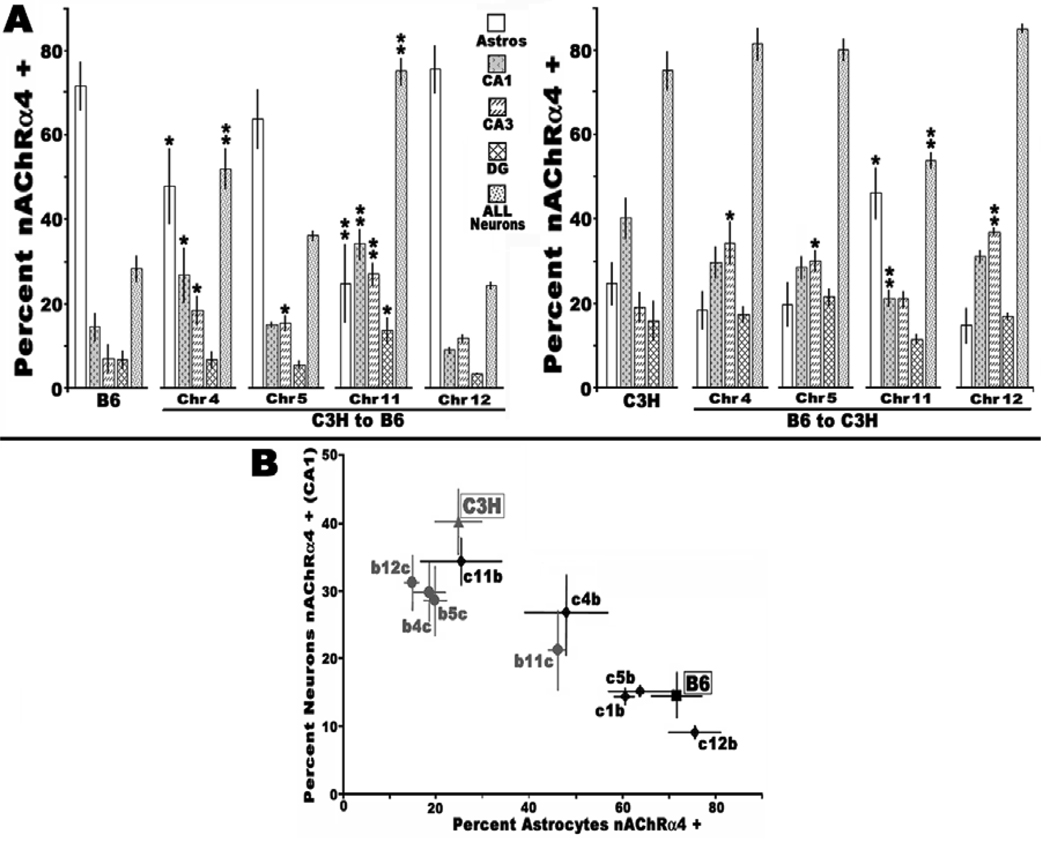

We measured if chromosomal sub-regions harbor genes that impact directly (either in cis or trans) upon the strain-specific nAChR expression in the hippocampus. For this analysis, C3H and C57BL/6 mice congenic for QTL regulating inflammatory pathologies were assessed for nAChR expression within the hippocampus. Coronal sections from the dorsal hippocampal CA1 region of either adult C3H or B6 congenic mouse strains congenic for Bb1, Bb2Bb3, Bb4, Bb6, and Bb12 on chromosomes 4, 5, 11 and 12 (see Methods) were prepared (Figure 1) and the relative number of nAChRα4 immunostained neurons or astrocytes in the dorsal hippocampus quantitated (Figure 2). While most congenic lines resemble closely their parental strain of origin (Figure 2a), there was a notable and statistically persistent difference in mice congenic for the Bb4 region of chromosome 11. For both C3.B6-Bb4 and B6.C3-Bb4 the relative ratio of nAChRα4 immunopositive astrocytes versus neurons was reversed. This was true for all animals examined (N=8 from at least three different litters) and was independent of gender. This effect was not generalized through the entire hippocampal field since in no case did nAChR expression in the dentate gyrus differ from the parent strain (not shown). In the hippocampal CA1 and CA3 subdivisions, notable differences in nAChR expression by astrocytes and neurons in some congenic lines were detected. The CA3 region, which only rarely harbors nAChR+ astrocytes, expressed more nAChRα4+ neurons relative to the parental strains in all congenic lines except B6.C3-Bb6, where the C3H Bb6 was introgressed onto the B6 background. Because of this generalized increased neuronal expression of nAChRα4 in CA3, it is likely that this effect is related to non-specific effects such as hybrid vigor and it is not relevant to strain background differences in nicotine response presently being studied. Therefore, our examination of these strains is focused on CA1.

Figure 1.

Expression of nAChRα4 in the dorsal hippocampus of B6 and C3H and congenic lines. Coronal sections of the dorsal hippocampus (CA1) revealing nAChRα4 expression are shown for parental strains C57BL/6 (B6) and the indicated reciprocal congenic strains. Prominent strain-specific differences in nAChRα4 expression are revealed by comparing the numbers of interneurons (arrowheads highlight examples), which dominate in C3H, versus astrocytes (arrows), which are most apparent in B6. Sections taken form mice harboring reciprocally exchanged portions of chromosomes (large numbers to left) that were introgressed into the recipient strain background are also shown. For mice receiving portions of chromosome 11, the relative abundance of nAChRα4 expressing astrocytes relative to the parental strain is reversed. Abbreviations are: stratum radiatum (sr); stratum oriens (so); and the pyramidal layer (py).

Figure 2.

Statistical analysis of interneuron versus astrocyte staining for nAChRα4 between B6 and C3H control and congenic mice. Panel A. Quantitation of results shown in Figure 1 for chromosomes 4, 5, 11 and 12, respectively, are shown. Regional analysis of dorsal hippocampal immunostaining for nAChRα4 in astrocytes (Astros) and inhibitory interneurons of hippocampal subregions CA1 and CA3 and the dentate gyrus (DG). The results of statistical analyses (Students T-test) comparing a congenic strain harboring the indicated chromosome (Chr) strain with its parental background is indicated (*, p<0.05; **, p<0.01). The majority of significant differences are located within mice harboring the reciprocal chromosome 11 congenic intervals. Some differences in other regions, such as chromosome 4 in the B6 background (but not the reciprocal comparison) are also present. Panel B. Each congenic line tested according to strain background (C3H, grey (c); B6, black (b)) is plotted based upon the percent of nAChRα4+ neurons versus astrocytes. The congenic mice retain the linear nAChR+ interneuron:astrocyte relationship consistent with parental origin except those harboring chromosome 11, which are reversed. The c4b mouse, however, exhibits only a partial penetrance of the strain-specific nicotinic interneuron:astrocyte expression ratio.

The ratio of the total nAChRα4+ astrocytes versus neurons as defined within the hippocampal CA1 subregion are inversely interrelated (see Figure 2 and (Gahring et al., 2004a). All congenic animal examined adhere to this inverse-relationship and overall the quantitative relationship predicted by the parental strain background is retained. However, two congenic strains fail to adhere to the this predicted neuron:astrocyte relationship. One significant deviation was in the chromosome 4 B6.C3-Bb1 mice. Here the relationship between neurons and astrocytes fell quantitatively almost exactly between the parental strains (Figure 2B). In contrast, the reciprocal chromosome 4 C3.B6-Bb1 strain exhibited a ratio almost identical to the parental C3H background. The other congenic strain to deviate quantitatively from the anticipated neuron:astrocyte ratio is the chromosome 11 C3.B6-Bb4 (Figure 2B), which also exhibits an intermediate phenotype. In this case, however, because the relative expression of nAChRs between CA1 neurons and astrocytes is exchanged by chromosome 11, the reciprocal B6.C3-Bb4 strain is statistically identical to the C3H strain. Of note is that in both cases, the reduced number of nAChR+ astrocytes relative to neurons is related either to the B6 background or a strain harboring the B6 chromosome 11 QTL. Therefore, this results argues that the discrepancy in the reciprocal exchange of this phenotype in these mouse strains predicts additional genes (e.g. on chromosome 4 or elsewhere) are likely to impact upon this phenotype of hippocampal morphology. Hence, an additional more detailed analysis, possibly of an interaction among modifiers on chromosome 4 and the B6 chromosome 11, is indicated before the reason for these deviations from the anticipated phenotype can be clarified.

The apparent switch between nAChR expression by interneurons versus astrocytes in the CA1 hippocampus mice congenic for chromosome 11 (Bb4) also reveals another aspect of how this strain-specific anatomical phenotype is related. As shown in Figure 3, the spatial arrangement of interneurons in the vicinity of the pyramidal cell layer in B6 mice coronal sections prepared slightly off center to the axis (~5°–10° tilt) reveals them to be spaced at approximately 100–150 micron intervals (Gahring et al., 2004a). This phenotype is more difficult to resolve in C3H mice due to the greater number of interneurons expressing nAChRs. The retention of the B6 spacing of nAChR immunostained neurons by C3.B6-Bb4 mice is notable whereas this pattern in the reciprocal B6.C3-Bb4 mouse is more intermediate between parental strains. In both cases, however, nAChRα4+ astrocytes are most abundant in stratum radiatum near the distal dendritic terminals of the comparably immunostained neurons. An additional detailed analysis of adjacent hippocampal formation regions is also indicated since a preliminary survey (not shown) suggests that dentate gyrus outer-molecular layer nAChR neurons are present in the C3.B6-Bb4 strain, which is expected of the C3H, but not B6, expression pattern (Gahring and Rogers, 2008). Hence, this result suggests that the neuronal:astrocyte relationship may be more complicated that suggested by the simple correlations observed and possibly related to additional strain or epigenetic determinants (see Discussion). These findings do however support the conclusion that regulation of nAChR expression by astrocytes, or possibly the origin of nAChR+ astrocytes, is encoded by genes within Bb4 interval of chromosome 11, and that other more subtle aspects of how these entities are spatially arranged are interactive with other genomic regions.

Figure 3.

High magnification of the dorsal hippocampus immunostained for nAChRα4 between control C57BL/6 and C3H mice and derived the chromosome 11 (Bb4) congenic mouse lines. In this example the relative abundance of nAChRα4 expressing astrocytes (arrows) coincide with the parental strain chromosome 11 QTL. However, the previously described (Gahring et al., 2004a) regular spacing of nAChR+ interneurons (asterisks, as shown for B6) at 100–150 micron intervals as described) is retained relative to the parental background.

DISCUSSION

This study further resolves that genetic component(s) contribute to strain-dependent variation in nAChR expression by cells of the dorsal hippocampus (Gahring et al., 2004a; Gahring et al., 2005; Gahring and Rogers, 2008). We specifically tested the hypothesis that a genetic contribution underlies the phenotype of a difference in nAChR expression by neurons or astrocytes in the hippocampus. It was observed that congenic lines prepared from C3H and C57BL/6 mice, in which the Bb4 region (chromosome 11) was reciprocally exchanged, exhibit an exchange in the nAChR astrocyte expression phenotype compared to the parental strain background. This effect appears to be specific to chromosome 11 since additional congenic lines harboring reciprocal exchanges between portions of chromosomes 4, 5 and 12, respectively, retained the parental nAChR expression phenotype. Collectively this result reveals the presence of genetic components that in combination determine the expression of nAChRs within the strain-dependent context of hippocampal morphology.

Because the expression of nAChRs by different cell types of the hippocampus is, at least in part, controlled by the strain specific genetic background (Stevens et al., 1996; Booker and Collins, 1997; Crawley et al., 1997; Stitzel et al., 2000; Adams et al., 2001; Dobelis et al., 2002; Gahring et al., 2004a; Gahring et al., 2005b; Graham et al., 2003; Lester et al., 2003; Alkondon et al., 2007), this introduces the potential for considerable functional complexity in the neuromodulatory impact of this receptor system on neurotransmission. In previous studies of nAChR expression and co-localization by cell subtypes of the mouse hippocampus CA1 region, it was found that while all nAChRα4+ immuno-stained neurons were also co-labeled by antibodies to glutamic acid dehydrogenase (GAD), not all GAD+ interneurons express nicotinic receptors (Gahring et al., 2004a; Gahring et al., 2004b; Gahring and Rogers, 2008 and not shown). This is consistent with many studies reporting heterogeneity in hippocampal interneurons as defined by the co-expression of multiple neurotransmitter systems (Alkondon and Albuquerque, 2004; Santhakumar and Soltesz, 2004). In terms of nicotinic receptor expression there are at least three interneuron subtypes that can be distinguished based upon functional measurements (Ji et al., 2001; McGehee, 2002; Alkondon and Albuquerque, 2004). Further, the balance in expression of these varied nAChRs contributes to distinct regional patterns of local excitatory:inhibitory modulation, and these differences among strains has been shown to quantitatively impact upon the balance in circuitry inhibitory tone (e.g., Alkondon et al., 2007). Astrocytes in the hippocampus also express functional nAChRs and different receptor subunits (e.g., Sharma and Vijayaraghavan, 2001; Hosli et al., 1994; Graham et al., 2003; Gahring et al., 2004b; Patti et al., 2007; Gahring and Rogers, 2008]). Therefore, it is likely that both differences in neuronal expression of nAChRs together with varied astrocyte expression will impact upon the neuromodulatory role of these receptors in the hippocampus and would be expected to contribute to the strain-specific influences of nicotine. It will also be of importance to assess possible interactions in strain dependent interneuron expression of other nAChRs as identified by QTL analysis of chromosome 7 (Adams et al., 2001). In practical terms, the considerable complexity in the genetics that control nAChR expression suggest that studies of animals from mixed or poorly defined strain backgrounds could impact on functional phenotypes to either enhance or obscure the impact of this receptor system.

It would also seem likely that these findings will be eventually extended to include differences in other brain regions since substantial strain-specific variability in nAChR expression has been reported for the striatum (Altavista et al., 1987) as well as the retina (Kang et al., 2004) and cerebellum (Turner and Hooper, 1999). Also, there is likely to be an age-related component to the influence differential expression of nAChRs has on local brain circuitry since the relative expression of nAChRs by interneurons and astrocytes is dynamic throughout the mouse life (Gahring et al., 2005). This finding corresponds well with studies reporting that strain-dependent relationships (including in humans) between neurons and astrocytes do indeed change with age and in various pathologies (Graham et al., 2002; Graham et al., 2003; Hosli et al., 2000; Teaktong et al., 2003)). Age related changes in the expression of genes located in this chromosome 11 QTL are presently being examined.

The identification of a genetic interval on Chromosome 11 that alters the nAChR expression profile leads to speculation of genes that could be responsible for this phenotype. Unlike the study of Adams and colleagues, who identified the nAChRα7 locus on chromosome 7 (Adams et al., 2001) to co-segregate with differences they detected in hippocampal morphology between C3H and DBA2 congenic analyses, there are no nAChR subunits encoded by the genomic interval identified on chromosome 11 in this study. However, it is not surprising that multiple genes, both those directly associated with nicotinic receptor expression and function or the context within which the receptor is expressed can contribute to phenotypic variations. For example, genes contributing to the strain-specific psychostimulant effects of nicotine have been identified on chromosome 11 in the vicinity of the D11Mit82 marker (Gill and Boyle, 2005a). There are also reports that chromosome 11 harbors a QTL correlating with risk of alcohol withdrawal (alcw3 at 18 cM; (Buck et al., 1997)), which is also near a cluster of GABA receptor subunits (19 cM; (Hood and Buck, 2000)). An additional gene that impacts upon hippocampal size on chromosome 11 is growth hormone (GH), which is expressed in the hippocampus (Fujikawa et al., 2000; Sun et al., 2005) and is subject to altered expression as a consequence of aging, glucocorticoids, and processes leading to memory formation (Donahue et al., 2002). Although there is a relationship of GH expression to development and aging, which are key co-variants of this nAChR phenotype (Gahring and Rogers, 2008), mapping of GH places it approximately 0.5cM outside of the Bb4. Similarly, hipp5, which is an member of the hipp gene family whose function is related to hippocampal size and susceptibility to anxiety (Gill and Boyle, 2005b; Lu et al., 2001), also is outside of the congenic QTL interval identified in this study. Nevertheless, the possibility that disruption of regulatory regions that control gene expression perhaps due to local chromosome breaks and re-associations generated during QTL exchange cannot not be ruled-out. Finally, an intriguing possibility are the candidate genes Nf1 and Trp53, located at Chr11 79375599 – 79375739 (NF1). Reilly and colleagues (Reilly et al., 2004) find that the modifier gene(s) responsible for differences in mouse strain susceptibility to astrocytomas in mice is closely linked to Nf1 and Trp53. Strains that harbor the dominant susceptibility alleles at the modifier locus are B6, A, and DBA/2 whereas 129-strains and CBA carry recessive resistance alleles. This coincides with the strain-dependent and cell-specific nAChR expression reported previously (see Gahring et al., 2004a; Gahring and Rogers, 2008). If indeed the penetrance of modifiers that influence astrocytes are present, the possibility of imprinting or an epigenetic component would be also suggested since the inheritance of these genes from the male increases susceptibility to astrocytoma in contrast to decreased susceptibility if inherited from the female (Reilly et al., 2004). This is an interesting direction for future studies.

Finally, translation of these findings between species and especially to humans is encouraged by comparative genomic studies that identify the mouse Bb4 chromosome 11 QTL interval to be syntenic with human chromosome 17. Since our findings are compatible with a model that local genetic elements control the establishment of strain-specific nAChR hippocampal morphology, then it might also be likely that similar mechanisms impacting on morphological determinants in humans will be present and will contribute to determinants of the individual susceptibility and response to nicotine.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NIH grants AG17517, DA015148, AI-43521, AI-42032 and NIDA/NHBLI grant PO1 HL72903. Thanks to Steele McIntyre for assistance with immunohistochemistry.

REFERENCES

- Adams CE, Stitzel JA, Collins AC, Freedman R. Alpha7-nicotinic receptor expression and the anatomical organization of hippocampal interneurons. Brain Res. 2001;922(2):180–190. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkondon M, Albuquerque EX. A non-alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor modulates excitatory input to hippocampal CA1 interneurons. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87(3):1651–1654. doi: 10.1152/jn.00708.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkondon M, Albuquerque EX. The nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes and their function in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex. Prog Brain Res. 2004;145:109–120. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(03)45007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkondon M, Pereira EF, Potter MC, Kauffman FC, Schwarcz R, Albuquerque EX. Strain-specific nicotinic modulation of glutamatergic transmission in the CA1 field of the rat hippocampus: August Copenhagen Irish versus Sprague-Dawley. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97(2):1163–1170. doi: 10.1152/jn.01119.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altavista MC, Gozzo S, Iacopino C, Albanese A. A genetic study of neostriatal cholinergic neurones in C57BL/6 and DBA/2 mice. Funct Neurol. 1987;2(3):273–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booker TK, Collins AC. Long-term ethanol treatment elicits changes in nicotinic receptor binding in only a few brain regions. Alcohol. 1997;14(2):131–140. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(96)00116-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck KJ, Metten P, Belknap JK, Crabbe JC. Quantitative trait loci involved in genetic predisposition to acute alcohol withdrawal in mice. J Neurosci. 1997;17(10):3946–3955. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03946.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crandall H, Ma Y, Dunn DM, Sundsbak RS, Zachary JF, Olofsson P, Holmdahl R, Weis JH, Weiss RB, Teuscher C, et al. Bb2Bb3 regulation of murine Lyme arthritis is distinct from Ncf1 and independent of the phagocyte nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase. Am J Pathol. 2005;167(3):775–785. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62050-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawley JN, Belknap JK, Collins A, Crabbe JC, Frankel W, Henderson N, Hitzemann RJ, Maxson SC, Miner LL, Silva AJ, et al. Behavioral phenotypes of inbred mouse strains: implications and recommendations for molecular studies. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;132(2):107–124. doi: 10.1007/s002130050327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobelis P, Marks MJ, Whiteaker P, Balogh SA, Collins AC, Stitzel JA. A polymorphism in the mouse neuronal alpha4 nicotinic receptor subunit results in an alteration in receptor function. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62(2):334–342. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.2.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahue CP, Jensen RV, Ochiishi T, Eisenstein I, Zhao M, Shors T, Kosik KS. Transcriptional profiling reveals regulated genes in the hippocampus during memory formation. Hippocampus. 2002;12(6):821–833. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin KBJ, Paxinos G. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. San Diego: Academic Press, Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fujikawa T, Soya H, Fukuoka H, Alam KS, Yoshizato H, McEwen BS, Nakashima K. A biphasic regulation of receptor mRNA expressions for growth hormone, glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid in the rat dentate gyrus during acute stress. Brain Res. 2000;874(2):186–193. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02576-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gahring LC, Persiyanov K, Dunn D, Weiss R, Meyer EL, Rogers SW. Mouse strain-specific nicotinic acetylcholine receptor expression by inhibitory interneurons and astrocytes in the dorsal hippocampus. J Comp Neurol. 2004a;468(3):334–346. doi: 10.1002/cne.10943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gahring LC, Persiyanov K, Rogers SW. Neuronal and astrocyte expression of nicotinic receptor subunit beta4 in the adult mouse brain. J Comp Neurol. 2004b;468(3):322–333. doi: 10.1002/cne.10942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gahring LC, Persiyanov K, Rogers SW. Mouse strain-specific changes in nicotinic receptor expression with age. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26(6):973–980. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gahring LC, Rogers SW. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor expression in the hippocampus of 27 mouse strains reveals novel inhibitory circuitry. Hippocampus. 2008 doi: 10.1002/hipo.20430. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill KJ, Boyle AE. Genetic basis for the psychostimulant effects of nicotine: a quantitative trait locus analysis in AcB/BcA recombinant congenic mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2005a;4(7):401–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2005.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill KJ, Boyle AE. Quantitative trait loci for novelty/stress-induced locomotor activation in recombinant inbred (RI) and recombinant congenic (RC) strains of mice. Behav Brain Res. 2005b;161(1):113–124. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham A, Court JA, Martin-Ruiz CM, Jaros E, Perry R, Volsen SG, Bose S, Evans N, Ince P, Kuryatov A, et al. Immunohistochemical localisation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits in human cerebellum. Neuroscience. 2002;113(3):493–507. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00223-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham AJ, Ray MA, Perry EK, Jaros E, Perry RH, Volsen SG, Bose S, Evans N, Lindstrom J, Court JA. Differential nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit expression in the human hippocampus. J Chem Neuroanat. 2003;25(2):97–113. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(02)00100-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood HM, Buck KJ. Allelic variation in the GABA A receptor gamma2 subunit is associated with genetic susceptibility to ethanol-induced motor incoordination and hypothermia, conditioned taste aversion, and withdrawal in BXD/Ty recombinant inbred mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24(9):1327–1334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosli L, Hosli E, Winter T, Stauffer S. Coexistence of cholinergic and somatostatin receptors on astrocytes of rat CNS. Neuroreport. 1994;5(12):1469–1472. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199407000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosli E, Ruhl W, Hosli L. Histochemical and electrophysiological evidence for estrogen receptors on cultured astrocytes: colocalization with cholinergic receptors. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2000;18(1):101–111. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(99)00074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji D, Lape R, Dani JA. Timing and location of nicotinic activity enhances or depresses hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2001;31(1):131–141. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jucker M, Bondolfi L, Calhoun ME, Long JM, Ingram DK. Structural brain aging in inbred mice: potential for genetic linkage. Exp Gerontol. 2000;35(9–10):1383–1388. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00190-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang TH, Ryu YH, Kim IB, Oh GT, Chun MH. Comparative study of cholinergic cells in retinas of various mouse strains. Cell Tissue Res. 2004;317(2):109–115. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-0907-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester HA, Fonck C, Tapper AR, McKinney S, Damaj MI, Balogh S, Owens J, Wehner JM, Collins AC, Labarca C. Hypersensitive knockin mouse strains identify receptors and pathways for nicotine action. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2003;6(5):633–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Airey DC, Williams RW. Complex trait analysis of the hippocampus: mapping and biometric analysis of two novel gene loci with specific effects on hippocampal structure in mice. J Neurosci. 2001;21(10):3503–3514. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-10-03503.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks MJ, Campbell SM, Romm E, Collins AC. Genotype influences the development of tolerance to nicotine in the mouse. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;259(1):392–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks MJ, Stitzel JA, Collins AC. Genetic influences on nicotine responses. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1989;33(3):667–678. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(89)90406-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGehee DS. Nicotinic receptors and hippocampal synaptic plasticity … it's all in the timing. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25(4):171–172. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)02127-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patti L, Raiteri L, Grilli M, Zappettini S, Bonanno G, Marchi M. Evidence that alpha7 nicotinic receptor modulates glutamate release from mouse neocortical gliosomes. Neurochem Int. 2007;51(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR, Caldarone BJ, Brunzell DH, Zachariou V, Stevens TR, King SL. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit knockout mice: physiological and behavioral phenotypes and possible clinical implications. Pharmacol Ther. 2001;92:89–108. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(01)00161-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peirce JL, Chesler EJ, Williams RW, Lu L. Genetic architecture of the mouse hippocampus: identification of gene loci with selective regional effects. Genes Brain Behav. 2003;2(4):238–252. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-183x.2003.00030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly KM, Tuskan RG, Christy E, Loisel DA, Ledger J, Bronson RT, Smith CD, Tsang S, Munroe DJ, Jacks T. Susceptibility to astrocytoma is mice mutant for Nf1 and Trp53 is linked to chromosome 11 and subject to epigenetic effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(35):13008–13013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401236101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SW, Gahring LC, Collins AC, Marks M. Age-related changes in neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit alpha4 expression are modified by long-term nicotine administration. J Neurosci. 1998;18(13):4825–4832. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-13-04825.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roper RJ, Weis JJ, McCracken BA, Green CB, Ma Y, Weber KS, Fairbairn D, Butterfield RJ, Potter MR, Zachary JF, et al. Genetic control of susceptibility to experimental Lyme arthritis is polygenic and exhibits consistent linkage to multiple loci on chromosome 5 in four independent mouse crosses. Genes Immun. 2001;2(7):388–397. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santhakumar V, Soltesz I. Plasticity of interneuronal species diversity and parameter variance in neurological diseases. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27(8):504–510. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma G, Vijayaraghavan S. Nicotinic cholinergic signaling in hippocampal astrocytes involves calcium-induced calcium release from intracellular stores. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(7):4148–4153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071540198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens KE, Freedman R, Collins AC, Hall M, Leonard S, Marks MJ, Rose GM. Genetic correlation of inhibitory gating of hippocampal auditory evoked response and alpha-bungarotoxin-binding nicotinic cholinergic receptors in inbred mouse strains. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;15(2):152–162. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(95)00178-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitzel JA, Lu Y, Jimenez M, Tritto T, Collins AC. Genetic and pharmacological strategies identify a behavioral function of neuronal nicotinic receptors. Behav Brain Res. 2000;113(1–2):57–64. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00200-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun LY, Al-Regaiey K, Masternak MM, Wang J, Bartke A. Local expression of GH and IGF-1 in the hippocampus of GH-deficient long-lived mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26(6):929–937. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teaktong T, Graham A, Court J, Perry R, Jaros E, Johnson M, Hall R, Perry E. Alzheimer's disease is associated with a selective increase in alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor immunoreactivity in astrocytes. Glia. 2003;41(2):207–211. doi: 10.1002/glia.10132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner AJ, Hooper NM. Role for ADAM-family proteinases as membrane protein secretases. Biochem Soc Trans. 1999;27(2):255–259. doi: 10.1042/bst0270255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimer RE, Wimer CC, Vaughn JE, Barber RP, Balvanz BA, Chernow CR. The genetic organization of neuron number in Ammon's horns of house mice. Brain Res. 1976;118(2):219–243. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90709-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]