Abstract

Objective

To examine the role of patient, family, and treatment variables on self-reported engagement for physicians and nurses working with pediatric complex care patients.

Methods

Sixty-eight physicians and 85 registered nurses at a children’s hospital reviewed eight case scenarios that varied by the patient and patient’s family (each cooperative vs. difficult) and the length of hospitalization (<30 vs. >30 days). Participants rated their engagement from highly engaged/responsive to distancing/disconnected behaviors.

Results

Nurses were more likely than physicians to engage in situations with a difficult patient/cooperative family but less likely to engage in situations with a cooperative patient/difficult family. Nurses were more likely to consult a colleague regarding the care of a difficult patient/difficult family, while physicians were more likely to refer a difficult patient/difficult family to a psychosocial professional.

Conclusions

Differences were found for engagement with “difficult” patients/families, with physicians more likely to distance themselves or refer to a psychosocial professional, while nurses were more likely to consult with a colleague.

Practice Implications

Communication between health care team members is essential for optimal family centered health care. Thus, interventions are needed that focus on communication and support for health care teams working with pediatric complex care patients and their families.

Keywords: complex care patients, difficult patients, communication, staff engagement

1. Introduction

“Complex care patients” have been described as children and adolescents with multifaceted medical regimens, psychiatric diagnoses, and/or behavioral/developmental issues. These patients often require not only complicated medical care, but also psychosocial support for the child and his/her family.(1–3) Psychosocial issues for complex care patients may include little or no family support, inconsistent care/caregivers, or multiple living environments. Complex care patients provide a unique challenge in the inpatient pediatric setting as they often have prolonged hospitalizations, complex treatment plans that involve multiple health care teams, as well as psychosocial concerns about the patient and/or caregiver. Together these factors may impair family centered care and fragment services.(2,4,5) For both physicians and nurses a breakdown in the relationship with patients can be frustrating. In addition, this may result in the desire to limit the amount of patient/family interaction to only that which is medically necessary. With family centered care recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Hospital Care,(6) the collaboration between physicians, nurses, and families is essential for patient outcomes.(1) Thus, it is important to understand the variables that may be associated with the level of engagement of physicians and nurses who work with pediatric complex care patients and their families.

What sets complex care patients apart from other medically complex patients are the psychosocial issues.(1) This often results in complex care patients being labeled as “difficult,” potentially resulting in disengagement by staff. Only a limited number of reports have examined pediatric complex care patients, yet multiple reports of the “difficult patient” are found in the adult medical literature.(7,8) Like the complex care patient, the “difficult patient” typically has psychosocial issues (e.g., personality disorder, substance abuse) and behavior problems (e.g., demanding behaviors, aggressive behaviors, non-adherence) in addition to their medical diagnosis.(9,10) Further, for patients with complicated medical issues, family disagreement (with one another or with the health care team) can add to the perception of a difficult patient.(4,11) One study reported that the second most likely reason to call an ethics consultation among physicians was to seek assistance with how to interact with a difficult patient and/or family member.(11) Each of these studies have emphasized the importance of physician-patient communication when working with “difficult” or complex care patients.

In pediatrics it is often the case that communication between physicians and patients requires only cursory attention when the child’s medical condition is stable and the family is coping well with the child’s illness.(12) However, when the child is a complex care patient the medical and psychosocial variables involved with the child’s care can contribute to tensions and conflicts in both the relationship between the family and staff, as well as the relationship among health care team members. When such conflicts intensify staff responses vary. Some physicians may refer patients for psychological or psychiatric consultation (10), while some nursing staff may request not to be assigned to the patient or avoid confronting issues beyond those that are necessary to provide medical care.(1,13)

In most situations physicians and nurses develop relationships with patients allowing for excellence in family centered care. However, when working with a complex care patient and his/her family, these relationships may become stressed causing staff to disengage from their patients. As this area has been previously unexplored, this study was undertaken to explore the role of patient, family, and treatment variables on staff perceptions of their own engagement with pediatric complex care patients. The aims of this study were: (1) to examine the relationship between the self-reported levels of engagement of physicians and nurses and patient, family, and length of hospitalization variables; (2) to examine the relationship between the self-reported levels of engagement of physicians and nurses and the demographics of the respondents; and (3) to compare the self-reported levels of engagement of physicians and nurses when working with complex care patients. Because this was an exploratory study, no a priori hypotheses were formed.

2. Methods

2.1.1 Study Setting

Participants were recruited from a large tertiary care children’s hospital (899 attending physicians, 2231 registered nurses). A team approach is utilized for inpatient care including resident physicians, medical fellows (post-residency specialist training), registered nurses, and other professional staff. Psychosocial care is interdisciplinary but primarily the responsibility of social workers, psychologists, the behavioral health team, and clinical nurse specialists. Social workers do some screening of patients for psychosocial issues; however, a majority of their work is initiated after screening by other members of the health care team.

Physician and nursing roles differ in our institution. Nurses are primarily responsible for around the clock care of 1–8 patients (depending on the severity of the child’s illness). Physician interactions are primarily in the area of directing care. Although physicians see patients on an outpatient basis, the constant rotation of attending physicians precludes most inpatients from being assigned to their regular physician.

2.1.2 Participants and Procedure

Participants included 68 physicians (attendings and fellows) and 85 registered nurses at a tertiary care children’s hospital (Table 1). Participants were broadly recruited across medical division and inpatient units including Cardiology, Critical Care Medicine, Endocrinology, General Pediatrics, Hematology, Oncology, and Pulmonary Medicine. During a regularly scheduled department or research meeting a member of the research team presented a short overview of the study (Appendix A) and distributed questionnaires. A verbal informed consent script was then read to participants stating that the completion of the anonymous questionnaire implied consent. This study was approved by the hospital’s Institutional Review Board.

Table 1.

Demographic Variables for Participants

| Physicians (n=68) |

Nurses (n=85) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M (SD) | Percent (n) | M (SD) | Percent (n) | p |

| Age (Yrs) | 40.7 (10.2) | 33.9 (9.3) | <.001 | ||

| Healthcare Experience (Yrs) | 14.1 (9.0) | 10.9 (9.4) | .02 | ||

| Sex (Female) | 41.2 (28) | 98.8 (84) | <.001 | ||

| Race | .23 | ||||

| Caucasian | 75.0 (51) | 80.0 (68) | |||

| African-American | 4.4 (3) | 9.4 (8) | |||

| Latino/Hispanic | 2.9 (2) | 2.4 (2) | |||

| Asian/Asian-American | 14.7 (10) | 4.7 (4) | |||

| Other | 2.9 (2) | 3.5 (3) | |||

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Vignettes

Eight short clinical vignettes were created for this study based on de-identified case summaries and the research team’s collective experience working with children, families, and care providers to resolve conflicts and tensions that arise as a result of complex medical and psychosocial circumstances. The research team included physicians, nurses (registered nurses and clinical nurse specialists), psychologists, social workers, and a biobehavioral statistician. Examples of the vignettes can be found in Appendix B. Each vignette consisted of details about the pediatric patient, the patient’s family, and the duration in which the patient had been hospitalized. The patient and family were described either as cooperative or non-cooperative with treatment and/or the health care staff, and the length of stay was less than or greater than 30 days. By combining these variables, eight scenarios were developed and refined with team members’ input. Prior to the current study, focus groups were conducted with 10 attending physicians and 10 experienced registered nurses who provided feedback about the readability and believability of the scenarios and questionnaire. In the current study, all participants read the same eight scenarios which were presented in random order.

2.2.2 Response questionnaire

For each of the eight scenarios, participants completed a two-part questionnaire (also developed for this study) with face-valid items to examine staff level of engagement. After reading each vignette participants were asked to keep in mind similar cases they may have worked with in their current position. In the first part of the questionnaire, participants were instructed: “Please circle the response that best represents how likely it would be for you to do each of the following behaviors.”

Use conversation to ease the patient’s and/or family’s intense emotions and pain

Call a family meeting to review/address medical care and/or psychosocial issues

Talk with a colleague about how to work with the patient/family’s emotional response

Make a referral to a professional who is specifically trained to manage the psychosocial aspects of pediatric specialty care

Avoid directly addressing the family’s emotional distress because it is a situation you are unlikely to change

Attend to the patient’s medical care during times that limit interactions within the family (e.g., meal time, family is not present, or rounds when you’ll be called away)

(RN version) Remove self from active care (e.g., calling in sick, requesting a “break,” or delegating to another team member (MD version) Other than your required duties as attending/fellow of record, remove yourself from active care because you no longer want to be involved with the family

For each behavior, participants chose one of four responses (labeled as ‘not at all likely’, ‘somewhat likely’, ‘likely’, ‘very likely’). The seven items were designed to range from highly engaged and responsive to the patient’s and family’s psychosocial concerns (behavior a) to disconnected and distancing (behavior g). The seven behaviors were created based on the research team members’ input and the feedback of the focus groups.

In the second part of the questionnaire for each scenario, participants were asked to rank the three “most likely actions” from the same list of seven behaviors.

2.3 General data analytic plan

We used the “profile analysis” method to apply repeated-measures ANOVA to assess the mean profiles of the seven responses (i.e., raw response ratings of items a – g).(14) Profile analysis was used to assess the three within-subject factors: patient cooperation (dichotomized as cooperative vs. difficult), family cooperation (also dichotomized as cooperative vs. difficult), and length of stay (dichotomized as less than and greater than 30 days). Differences across nurses and physicians on specific items (e.g., the percentages of nurses and physicians who would refer the patient/family case for psychology consult) were further analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. The raw responses to these seven questions were dichotomized from the 4-point response scale (likely/very likely versus not at all likely/somewhat likely). Confidence intervals for the odds ratios were obtained when possible. Chi-square analysis was utilized to compare the most likely response behavior for each scenario.

3. Results

3.1 Sample Characteristics

Statistically significant differences between physicians and nurses were found for age (t[147]=−4.3, p<0.001) and years of health care experience (t[149]=−2.3, p<0.001) with physicians being both older and reporting greater number of years in health care. A significant difference was also found for sex (X2[1]=64.0, p<0.001) with over half of the physicians, but only one nurse, male. No significant difference was found for race (X2 [4]=5.7, p=0.23). A summary of respondent characteristics is provided in Table 1.

3.2 Impact of Patient/Family Characteristics on Provider Engagement

3.2.1 Overall Profile Analysis

We examined the association between staff engagement, patient cooperation, family cooperation, and length of stay. A repeated-measure analysis of variance was performed. While significant main effects were found for patient (F[1,138}=49.9, p<0.001) and family (F[1,138]=62.3, p<0.001), no main effect was found for length of stay (F[1,138]=0.62, p=0.43). Thus the scenarios were collapsed across length of stay for all remaining analyses, resulting in four scenario combinations: cooperative patient, cooperative family (CP/CF); difficult patient, difficult family (DP/DF); cooperative patient, difficult family (CP/DF); difficult patient, cooperative family (DP/CF). While significant interactions were found for position (physician/nurse, descried below), no significant interactions were found for race, sex, or years of health care experience.

3.2.2 Staff Engagement

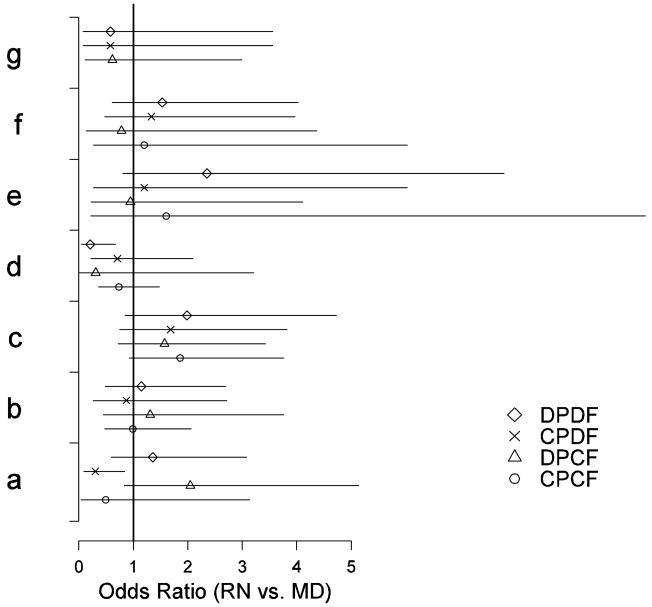

For each of the four scenario combinations we examined how likely participants were to engage in that behavior. As seen in Table 2 responses “a” through “d” were more common than responses “e” through “g”. To better understand and interpret these percentages, odds ratios were calculated comparing the percent of nurses versus physicians who were likely to engage in each of the seven behaviors. These odds ratios and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals are plotted in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Likelihood of staff engagement behaviors.

| Nurses n = 85 n (%) | Physicians n = 68 n (%) | OR (95% CI) RN vs. MD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staff Engagement | ||||

| Cooperative Patient, Cooperative Family (CP/CF) | ||||

| a. “ease patient’s and/or family’s intense emotions and pain” | 81 (95) | 66 (97) | .49 | (.05, 3.13) |

| b. “call a family meeting to review medical care and/or psychosocial issues” | 58 (68) | 47 (69) | .99 | (.47, 2.06) |

| c. “consult a colleague on addressing the patient/family’s emotional response” | 56 (66) | 34 (50) | 1.86 | (.93, 3.76) |

| d. “make a referral to a professional who is specifically trained … “ | 49 (58) | 43 (63) | .74 | (.36, 1.48) |

| e. “avoid directly addressing the family’s emotional distress …“ | 4 (5) | 2 (3) | 1.60 | (.22, 18.25) |

| f. “attend to the patients medical care during times that limit interactions …” | 6 (7) | 5 (7) | 1.20 | (.27, 6.03) |

| g. “remove yourself from active care” | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | - | - |

| Difficult Patient, Difficulty Family (DP/DF) | ||||

| a | 68 (80) | 50 (74) | 1.36 | (.60, 3.08) |

| b | 69 (81) | 53 (78) | 1.15 | (.48, 2.70) |

| c | 72 (85) | 49 (72) | 1.99 | (.85, 4.72) |

| d | 66 (78) | 65 (96) | .21 | (.05, .67)* |

| e | 17 (20) | 6 (9) | 2.35 | (.81, 7.80) |

| f | 19 (22) | 10 (15) | 1.53 | (.61, 4.03) |

| g | 3 (4) | 5 (7) | .58 | (.08, 3.56) |

| Difficult Patient, Cooperative Family (DP/CF) | ||||

| a | 74 (87) | 51 (75) | 2.05 | (.84, 5.14) |

| b | 76 (89) | 58 (85) | 1.31 | (.45, 3.76) |

| c | 67 (79) | 47 (69) | 1.57 | (.73, 3.43) |

| d | 82 (96) | 67 (99) | .31 | (.01, 3.21) |

| e | 5 (6) | 5 (7) | .95 | (.23, 4.11) |

| f | 4 (5) | 4 (6) | .78 | (.14, 4.37) |

| g | 4 (5) | 5 (7) | .62 | (.12, 2.99) |

| Cooperative Patient, Difficult Family (CP/DF) | ||||

| a | 65 (76) | 62 (91) | .30 | (.09, .84)* |

| b | 76 (89) | 61 (88) | .87 | (.27, 2.71) |

| c | 69 (81) | 48 (71) | 1.69 | (.75, 3.82) |

| d | 74 (87) | 61 (90) | .71 | (.22, 2.10) |

| e | 6 (7) | 5 (7) | 1.20 | (.27, 6.03) |

| f | 13 (15) | 8 (12) | 1.33 | (.48, 3.97) |

| g | 3 (4) | 4 (6) | .58 | (.08, 3.56) |

Note. Data are number of respondents and percentages. Odds Ratio obtained using Fisher’s exact test.

p < 0.05

Figure 1.

Odds ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals on how nurses differed from physicians in their perceived likelihood of engagement with a complex pediatric care case. The hypothetical behaviors ranged from highly supportive and engaging (behavior a) to exceedingly distancing and fragmented (behavior g). An odds ratio of 1.0 (vertical line) indicates that nurses and physician did not differ in their perceived likelihood of taking the target action. Nurses were marginally more likely than physicians to focus on the emotional concerns of a difficult patient/cooperative family pair (behavior a, marked by a triangle Δ, DPCF: OR = 2.05), while they were significantly less likely to do so than physicians for a cooperative patient/difficult family pair (behavior a, marked by an X, CPDF, OR = .30). Nurses were overall marginally more likely than physicians to consult a colleague on how to address the patient’s/family’s emotional response (behavior c, all 4 profiles) and significantly less likely, for a difficult patient/difficult family scenario, to make a referral to a professional who is specifically trained to manage the psychosocial aspects of pediatric specialty care (behavior d, marked by a diamond ⋄ DPDF, OR = .21). Nurses were also marginally more likely than physicians to avoid directly addressing the family’s emotional distress if they thought it was a situation they were unlikely to change (behavior e, DPDF, OR = 2.35).

Nurses were marginally more likely than physicians to focus on the emotional concerns of a difficult patient/cooperative family pair (DP/CF: OR = 2.05, 95% CI: [0.84, 5.14], p=.10), while they were significantly less likely to do so than physicians for a cooperative patient/difficult family scenario (CP/DF, OR = 0.30, 95% CI: [0.09, 0.84], p=.02). Nurses were overall marginally more likely than physicians to consult a colleague on how to address the patient’s/family’s emotional response, and significantly less likely to make a referral to a professional who is specifically trained to manage the psychosocial aspects of pediatric specialty care (behavior d, DP/DF, OR = 0.21, 95% CI: [0.05, 0.67], p=.003). Nurses were also marginally more likely than physicians to avoid directly addressing the family’s emotional distress if they thought it was a situation they were unlikely to change (behavior e, DP/DF, OR = 2.35, 95% CI: [0.81, 7.80], p=.11).

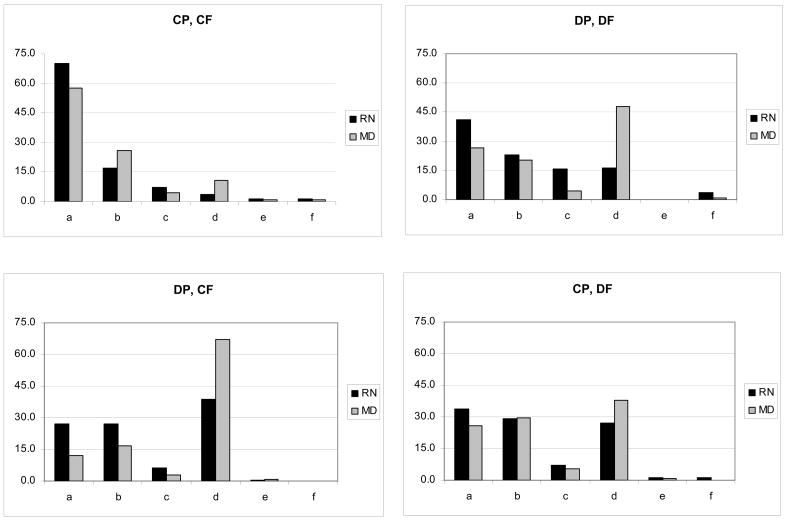

3.2.3 Most Likely Behavior

For each of the four scenario combinations we examined the most likely behavior in which respondents reported they would engage when working with the different combinations of patients and family members (see Figure 2). Chi-square analyses indicated that both physicians and nurses were more likely to engage when a patient and their family are considered “cooperative” (X2[5] = 11.1, p = 0.05). When there was a difficult patient, regardless of the family’s level of cooperation, physicians were significantly more likely to make a referral to a professional psychosocial colleague (X2[5] = 39.7, p = 0.00), while nurses were divided among the levels of engagement. For the cooperative patient/difficult family paring there were no significant differences between physicians and nurses for the level of patient engagement (X2[5] = 6.4, p = 0.3). Finally, although small in number, 4% of nurses reported that their first choice of behavior when there was a difficult patient and difficult family pair would be to distance themselves from the situation by attending to the patient’s medical care during times that limit interactions with the family.

Figure 2.

Representation of the behavior in which respondents were most likely to engage: (a) use conversation to ease patient’s and/or family’s intense emotions and pain, (b) call a family meeting to review/address medical care and/or psychosocial issues, (c) talk with a colleague about how to work with the patient’s/family’s emotional response, (d) make a referral to a professional who is specifically trained to manage the psychosocial aspects of pediatric specialty care, (e) avoid directly addressing the family’s emotional distress because it is a situation that you are unlikely to change, (f) attend to the patient’s medical care during times that limit interactions within the family. Response choice g (remove self from active care) was excluded as no one selected it as their first choice.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

4.1 Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study that has empirically examined staff engagement with pediatric complex care patients. The results of this study show that the perception of “difficult” patients and “difficult” family members is related to the staff’s level of engagement. In addition, the decision about when to refer the family to outside professionals who are trained specifically to handle the psychosocial aspects of pediatric medical care was associated with both patient and family variables. Based on our clinical experience, we expected that staff would be more likely to disengage with difficult patients/difficult families who had been hospitalized for more than 30 days, yet this association was not found. Similarly, no demographic variables (participant race, sex, and years of health care experience) were related to staff level of engagement. Finally, nurses and physicians reported different levels of engagement based on both patient and family variables.

Some of the differences in levels of engagement between nurses and physicians may be accounted for by the different roles that these team members play in the ongoing care of a hospitalized child. Nurses provide the front-line care for the patient with multiple opportunities per day to interact with the child and their family members. At our hospital, medical residents are often the front line physician responders, resulting in less interaction time for fellows and attendings who may see patients as little as once or twice a day (e.g., during rounds). The relationship between fellows and attending physicians with their patients may tend to be transient and discontinuous while the patient is admitted to the hospital. The relationship between nurses and their patients, however, may be more intimate, intensive, and continuous since they are assigned to care for the patient for 8, 12 or 16 hour shifts.

Based on the frequency and type of daily interactions, when physicians and nurses encounter a “difficult” patient or family the finding that their level of engagement differs is not surprising. The results from this study suggest that nurses were more likely than physicians to focus on the emotional and psychosocial issues of patients and family members if the family was cooperative, even if the patient was perceived as “difficult.” However, when the family was “difficult,” nurses were less likely than physicians to focus on emotional issues, with some even choosing to avoid directly addressing emotional distress if they thought it was a situation they were unlikely to change. In addition, while nurses were more likely to consult with a colleague (likely another nurse), physicians were more likely to refer a patient to a psychosocial professional. One potential explanation for this finding is that referrals to psychologists and psychiatrists at our institution can only be initiated by physicians, while nurses are able to consult with a member of a mental health clinical nurse specialist team who can provide additional guidance and support with complex care patients.

Communication is an essential part of providing family centered medical care, yet when a pediatric patient or their family is seen as “difficult” it may result in a disruption in communication patterns between the patient, family, and health care providers.(1,3,12) In an academic hospital, like the one in this study, there are two potential explanations for the breakdown in communication. First, as is common in most academic hospitals, attending physicians and fellows frequently rotate on and off service, while nurses continue to provide ongoing care to patients. Most physicians at our hospital are currently on service for less than two weeks at a time. Second, complex pediatric patients often require multiple specialty services with each consulting service providing another opportunity for communication to break down, not only between the patient/family and the health care team, but among health care providers. These situations may result in abrupt changes in medications, plans, and opinions, which may confuse and frustrate patients and their families. One potential intervention, a “difficult family protocol,” has been proposed for those working with pediatric complex care patients.(12) This protocol focuses on the need to recognize three players in a pediatric patient’s care: the child, the family, and the health care team. Another potential solution may be the use of physician hospitalists who would devote more time to the inpatient unit and provide greater continuity of care for patients.

While the nursing literature provides examples of working with complex care patients and their families(1,4) less is known about potential interventions that address conflicts and communication barriers among health care team members.(12,15) The results of this study suggest an association between difficult patients and/or families and distancing behaviors in nurses and physicians. Further exploration of these interactions is needed to also understand how team conflict and communication among health care team members affect physician and nurse engagement with patients/families.

The relationship between staff engagement and patient/family variables found in this study suggests a need to examine the breakdown in communication through an interpersonal lens. From this perspective three key points for understanding the complex pediatric patient are evident. First, staff must see themselves as entangled in an escalating cycle of conflict. Second, staff must appreciate how the focus on controlling or managing physical and behavioral symptoms can create a blind spot for the critical role that child-family-staff relationships play in promoting effective coping with serious, chronic, or life-threatening illness. Finally, health care providers have a responsibility to address these dynamics, but when patients are simply referred to a psychosocial professional this assumes the problem resides in the patient/family and does not require the attention of physicians and nurses. Thus, there is a need for interventions and support that enable physicians and nurses to collaborate and effectively work with both the medical and psychosocial issues seen in complex care patients.(16–18)

This study had a number of limitations falling into two categories: methodological and sample. Although our questionnaires were anonymous, participants may have given socially desirable answers, especially for more difficult patients/families. Despite this, there were still a small number of physicians and nurses who reported that they would remove themselves from the active care of the patient if possible. The clear distinction between less than 30 days and greater than 30 days may also have been limiting in identifying if health care providers become less engaged with patients who have longer hospitalizations. In our experience the 30 day mark is when “difficult” patients often come to the attention of hospital administration. However, this line of demarcation may not be so clear to health care providers. Further, in these scenarios we chose to only focus on personality and behavioral issues rather than medical issues, as we believe that conflicts that cause staff distancing behaviors may have little to do with the child’s medical management. However, it is possible that the medical intricacies of some complex care patients may also result in distancing behaviors.

Next, the use of vignettes may not have provided the most accurate representation of staff engagement. For example, the scenarios in this study focused solely on the relationship and interactions between the staff and the patient/family, but did not address the conflict that often arises between health care providers when working with complex care patients, especially when multiple health care teams are involved. Therefore, it is likely that we were unable to detect some of the reasoning behind why staff chose to engage or distance themselves from a particular patient. However, vignettes have been found to provide useful clinical information when observational studies are not financially, logistically, or ethically feasible.(19–21)

Further, the vignettes and questionnaire received only preliminary validation through the feedback of our focus groups. Additional research is needed to further validate this measure. Finally, the results of the study were interpreted as points on a continuum that represented decreasing levels of engagement; however, the results may better represent two different strategies for working with complex care patients: addressing psychosocial issues versus avoiding and/or distancing.

In terms of the study participants, the size of our sample may have limited the power to detect significant differences between nurses and physicians. In addition, we were unable to tease apart the impact of demographic variables such as age and sex (e.g., attendings were older than fellows, sample almost 100% female nurses). Future studies should include a larger population of participants to address these issues. The generalizability of the findings is also somewhat limited as the results are based on physicians and nurses at a single tertiary care children’s hospital. It is possible that staff engagement with complex patients may vary by the hospital size (small versus large), type (private versus university-based), geographic location, and resources available to staff (i.e., behavioral health team, staffing levels, private rooms, etc.).

4.3 Conclusion

The results from this exploratory study suggest that both nurses and physicians are less likely to engage with complex care patients if the patient and/or family are perceived as “difficult.” Differences found between physician and nurse responses to difficult pediatric complex care patients may be attributed to the health care provider’s role within the hospital and institutional practices (e.g., referral patterns, time on service). Interventions are needed that can assist both physicians and nurses to improve communication and cope with the medical and psychosocial issues seen in complex care patients.

4.3 Practice Implications

It is important for health care providers to recognize the importance of communication between the staff member and the patient/family, as well as between health care team members about a particular patient. In addition, since complex care patients often have multiple consulting services involved in their care, support is needed to facilitate communication between health care providers and teams who work together to address both the physical and psychosocial needs of pediatric complex care patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all current and former members of the Complex Care Consultation Team for their input on scenario development, as well as their assistance with data collection.

Support for Dr. Li’s contribution to this project came from the Weill Cornell Medical College Clinical and Translational Science Award (NIH UL1-RR024996).

All patient/personal identifiers have been removed or disguised so the patients/persons described are not identifiable and cannot be identified through the details of the story.

Appendix A

Participant Instructions

You are being invited to participate in a new research study being conducted by the Complex Care Consultation Team at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. We want to examine how medical and nursing staff respond to and interact with medically complex patients.

There is a lack of empirical research examining staff interactions with patients who require complex pediatric care. Your participation in this study will provide important information that will help us to understand the experience of physicians and nurses when working with these types of complex cases.

Appendix B

Cooperative Patient, Cooperative Family, LOS < 30 days

Faith is a 17-year old adolescent female suffering a traumatic brain injury who has been at CHOP for less than 30 days. Faith is a high school senior who secured an early admission and an academic scholarship to an Ivy League university. During a driving rainstorm, a fellow motorist found Faith bleeding and comatose in her over turned car. She was emergently transported to the emergency department. The neurosurgeon successfully stopped an intracranial bleed. She quickly stabilized in the pediatric intensive care unit. She was transferred to your floor where her pain, intracranial pressure and headache responded to treatment. Her lower extremity gross motor functioning remains impaired but is likely reversible. Her parents skillfully juggled their work and family lives to remain by Faith’s side. The previous attending told Faith and her parents that discharge was contingent on her mastering a transfer from the bed to a wheel chair. Her parents told you that the staff’s optimistic perspective is a key ingredient to her motivation to recover. In your role as the assigned nurse, which of the following would you likely perform?

Cooperative Patient, Difficult Family, LOS >30 days

Cory is a two-old toddler with a rare liver disease who has been at CHOP for more than 30 days. He has spent most of his life in the hospital. He is an inpatient and day 30-post transplant. Cory is a happy boy. He frequently engages in imaginative play with stuffed animals and action figurines. He easily calms himself to cooperatively make the transition from play to the physical exam. One or both of his parents are always present. Because of their extensive knowledge of his medical condition his parents insist on active participation in medical care. His mother approaches the staff in a low key and unassuming way. His father is anxious and demanding.. He becomes anxious when Cory suffers from medical effects of the transplant and infection. When the medical team modifies the care plan, he become frantic, publicly states, “If Cory dies, I will kill someone, ” and then storms off the unit, returning when he is calm. In your role as the physician, which of the following would you likely perform?

Difficult Patient, Cooperative Family, LOS <30 days

Jackson is a 13 year-old patient who has HIV and oppositional defiant disorder, and has been at CHOP for less than 30 days. Jackson has been admitted to the unit with an infection that requires IV antibiotics. Jackson has a history of being non-adherent with his anti-viral medications. Jackson is an angry kid and when he doesn’t get his way (e.g. being asked to stay in his room due to the contagious nature of the infection) he threatens to spit at staff and/or infect them with his HIV. He has been placed in the hospital for almost a month due to his antibiotic therapy and his foster parents are unable to manage his IV care at home. His foster parents are lovely people, but are overwhelmed with Jackson’s care and behavior. They are willing to do whatever it takes to make him better and are appreciative of any resources they are offered. They are always apologetic to the staff for Jackson’s behavior. In your role as the nurse assigned to the patient, which of the following would you likely perform?

Difficult Patient, Difficult Family, LOS > 30 days

Tony is an 11-year old boy with inflammatory bowel disease and anorexia who has been at CHOP more than 30 days. He was admitted to your floor for worsening abdominal pain. Throughout his stay, he has been uncooperative. He is argumentative and screams “no” when you attempt a physical exam and discuss nutrition. Because of the tantrums, it takes you longer than customary to complete rounds. He accuses you of “not caring.” His mother is always present. Rather than setting limits, she remains passive and makes excuses for his immature behavior. The evening nurses frequently report-smelling alcohol on her breath. In your role as the physician, which of the following would you likely perform on the last day of your service with this child and family?

Footnotes

Complex Care Consultation Team members that made significant contributions to this project (in alphabetical order): Karen Anderson, Deborah Lamb, Donna McKlindon, Howard Panitch, Paul Robins, Dolores Vorters

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sieben-Hein D, Steinmiller EA. Working with complex care patients. J Pediatr Nurs. 2005;20:389–95. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haas LJ, Leiser JP, Magill MK, Sanyer ON. Management of the difficult patient. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:2063–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kazak AE, Rourke MT, Alderfer MA, Pai A, Reilly AF, Meadows AT. Evidence-based assessment, intervention and psychosocial care in pediatric oncology: a blueprint for comprehensive services across treatment. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:1099–110. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tracy MF, Ceronsky C. Creating a collaborative environment to care for complex patients and families. AACN Clin Issues. 2001;12:383–400. doi: 10.1097/00044067-200108000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheldon LK, Barrett R, Ellington L. Difficult communication in nursing. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2006;38:41–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2006.00091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eichner JM, Neff JM, Hardy DR, Klein M, Percelay JM, Sigrest T, et al. Family-centered care and the pediatrician’s role. Pediatrics. 2003;112:691–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hahn SR, Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Brody D, Williams JB, Linzer M, et al. The difficult patient: Prevalence, psychopathology, and functional impairment. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:1–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02603477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson JL, Kroenke K. Difficult patient encounters in the ambulatory clinic: Clinical predictors and outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1069–75. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.10.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steinmetz D, Tabenkin H. The ‘difficult patient’ as perceived by family physicians. Fam Pract. 2001;18:495–500. doi: 10.1093/fampra/18.5.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krebs EE, Garrett JM, Konrad TR. The difficult doctor? Characteristics of physicians who report frustration with patients: an analysis of survey data BMC. Health Serv Res. 2006;6:128. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DuVal G, Sartorius L, Clarridge B, Gensler G, Danis M. What triggers requests for ethics consultations? J Med Ethics. 2001;27(Suppl 1):i24–i29. doi: 10.1136/jme.27.suppl_1.i24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simms S. A protocol for seriously ill children with severe psychosocial symptoms: Avoiding potential disasters. Family Systems Medicine. 1995;13:245–57. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daum AL. The disruptive antisocial patient: Management strategies. Nurs Manag. 1994;25:46–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maxwell SE, Delaney HD. Designing experiments and analyzing data. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sieben D, Steinmiller EA, Bertolino J. Nursing interventions for a chronically ill, nonadherent teenager with a psychiatric diagnosis. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2003;8:121–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1088-145x.2003.00121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kazak AE, Simms S, Rourke M. Family systems practice in pediatric psychology. J Pediatr Psychol. 2001;27:133–43. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simms S, Warner NJ. A framework for understanding and responding to the psychosocial needs of children with Langerhan’s cell histiocytosis and their families. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1998;12:359–67. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70515-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simms S, Kuh E, D’Angio G. Psychosocial aspects of the histiocyctic disorders: Staying on course under challenging clinical circumstances. In: Weitzman S, Egeler RM, editors. Histiocytic disorders of children and adults: Basic science, clinical features, and therapy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hughes R, Huby M. The application of vignettes in social and nursing research. J Adv Nurs. 2002;37:382–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gould D. Using vignettes to collect data for nursing research studies: how valid are the findings? J Clin Nurs. 1996;5:207–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.1996.tb00253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rethans JJ, Westin S, Hays R. Methods for quality assessment in general practice. Fam Pract. 1996;13:468–76. doi: 10.1093/fampra/13.5.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]