Abstract

PURPOSE We wanted to summarize evidence about the diagnostic accuracy of the 5.07/10-g monofilament test in peripheral neuropathy.

METHODS We conducted a systematic review of studies in which the accuracy of the 5.07/10-g monofilament was evaluated to detect peripheral neuropathy of any cause using nerve conduction as reference standard. Methodological quality was assessed using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS) tool.

RESULTS We reviewed 173 titles and abstracts of articles to identify 54 potentially eligible studies, of which 3 were finally selected for data synthesis. All studies were limited to patients with diabetes mellitus and showed limitations according to the QUADAS tool. Sensitivity ranged from 41% to 93% and specificity ranged from 68% to 100%. Because of the heterogenous nature of the studies, a meta-analysis could not be accomplished.

CONCLUSIONS Despite the frequent use of monofilament testing, little can be said about the test accuracy for detecting neuropathy in feet without visible ulcers. Optimal test application and defining a threshold should have priority in evaluating monofilament testing, as this test is advocated in many clinical guidelines. Accordingly, we do not recommend the sole use of monofilament testing to diagnose peripheral neuropathy.

Keywords: Peripheral neuropathy; peripheral nervous system diseases; monofilament testing; Semmes-Weinstein monofilament; review, systematic; primary health care; diabetic foot

INTRODUCTION

Peripheral neuropathy causes loss of sensation and increases the risk of ulceration of the feet. Timely identification of loss of protective sensation may allow preventive intervention. Peripheral neuropathy is a complication in approximately 50% of patients with diabetes, and up to 50% of patients with peripheral neuropathy may not have symptoms.1–3

Several tests are used to detect peripheral neuropathy, including vibration perception, application of warmth and cold, and nerve conduction studies, which are assumed to be the reference standard.4 Electrodiagnostic tests can be complex, expensive, and time consuming, which hampers their widespread use, especially in primary care, where for most patients peripheral neuropathy is diagnosed and treated.

Monofilament testing is an inexpensive, easy-to-use, and portable test for assessing the loss of protective sensation, and it is recommended by several practice guidelines to detect peripheral neuropathy in otherwise normal feet.1,5,6 Monofilaments, often called Semmes-Weinstein mono-filaments, are calibrated, single-fiber nylon threads, identified by values ranging from 1.65 to 6.65, that generate a reproducible buckling stress. The higher the value of the monofilament, the stiffer and more difficult it is to bend. Three monofilaments commonly used to diagnose peripheral neuropathy are the 4.17, 5.07 and 6.10.7–9 Forces required to bend these monofilaments are 1, 10, and 75 g, respectively. The filament is placed on the patient’s skin (usually the feet); when there is considerable loss of sensation, the patient will not be able to detect the presence of the filament at buckling. The 5.07/10-g monofilament has been described as the best indicator to determine loss of protective sensation.7,10–12 The aim of this review was to perform a meta-analysis of studies evaluating monofilament testing with the 5.07/10-g monofilament in diagnosing peripheral neuropathy of the feet from any cause.

METHODS

We searched MEDLINE and EMBASE from database inception to June 2007 to identify diagnostic accuracy studies of peripheral neuropathy that used monofilament testing. Our search strategy focused on monofilaments, peripheral neuropathy, and diagnostic studies. The complete strategy is available in Supplemental Appendix 1, available at http://annfammed.org/cgi/content/full/7/6/555/DC1). We applied no language restrictions, and we supplemented our searches by manually reviewing the reference lists of eligible studies.

Selection

Two reviewers (A.W., J.D.) independently selected potentially relevant studies by titles and abstracts. We included articles when peripheral neuropathy of the feet was the target condition, monofilament testing with a 5.07/10-g monofilament was the index test, and nerve conduction study was used as reference standard. If the 2 reviewers disagreed, consensus was sought with the help of a third reviewer (H.W.).. Of all possibly relevant articles, the full text was reviewed using the above-mentioned inclusion criteria.

Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of the studies was independently assessed by 2 reviewers (A.W., J.D.) using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS) checklist (the QUADAS checklist can be found in Supplemental Appendix 2, available at http://annfammed.org/cgi/content/full/7/6/555/DC1).13 In case of disagreement consensus was reached with a third reviewer (H.W.).

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Sensitivity and specificity were calculated from 2 × 2 tables or retrieved from data available in the primary articles. The aim of the review was to perform a meta-analysis.

RESULTS

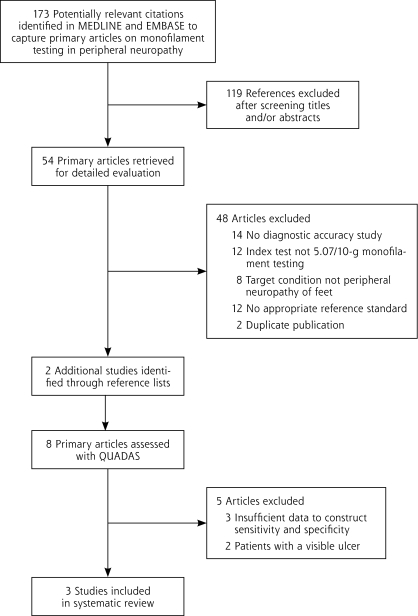

The study selection process is shown in Figure 1▶. The characteristics of the final assessed 3 diagnostic accuracy studies are shown in Table 1▶. All studies appeared to be limited to patients with diabetes mellitus. Sensitivity of the monofilament test ranged from 0.41 to 0.93, and specificity ranged from 0.68 to 1.00. All studies showed methodological limitations that could have inflated sensitivity or specificity. A meta-analysis could not be accomplished because of important differences in the methods of execution of the index test and relevant differences in thresholds defining conduction abnormalities.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study selection process.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Included Studies, With Nerve Conduction Study as Reference Standard

| Characteristic | Lee, 200314a,b | Perkins, 200115a,c | Shin, 200019d |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants n (% women) | 37 (46) | 478 (34) | 126 (54) |

| Age, mean, y | 59 | 54 | 58 |

| Population | Unselected type 2 diabetic outpatients in Pusan, Korea | a. 426 Unselected diabetic patients attending secondary and tertiary diabetic clinics, and recruited through advertisements b. 52 Nondiabetic reference subjects in Toronto General Hospital/University Health Network, Canada |

Consecutive diabetic patients referred to a secondary foot clinic in Seoul, Korea |

| Methods of monofilament testing | |||

| Sites, No. and Location | 10, Dorsal between base digit 1–2; ventral digit 1,3,5; MT heads 1,3,5; medial and lateral midfoot; heel | 1, Hallux | NR |

| Threshold | ≥ 5 of 10 incorrect (1 foot) | a. ≥ 5 of 8 incorrect (both feet) b. ≥ 2 of 8 incorrect (both feet) |

NR |

| Sensitivity (95% CI) | 93.1 (0.77–0.99) | a. 40.9 (0.36–0.46) b. 77.0 (0.72–0.81) |

56.7 (0.44–0.69) |

| Specificity (95% CI) | 100.0 (0.63–1.00) | a. 96.2 (0.90–0.99) b. 68.3 (0.58–0.77) |

94.9 (0.86–0.99) |

| LR+ (95% CI) | 16.5 (1.1–245.0) | a. 10.6 (4.0–28.0) b. 2.4 (1.8–3.2) |

11.2 (4.0–34.0) |

| LR– (95% CI) | 0.07 (0.02–0.26) | a. 0.61 (0.56–0.67) b. 0.34 (0.27–0.42) |

0.46 (0.35–0.60) |

CI=confidence interval; QUADAS = Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies, LR = likelihood ratio; MT = metatarsal, NR = not reported.

a QUADAS limitation: selection criteria not clearly described.

b QUADAS limitation: test results possibly not interpreted without knowledge of the other test results.

c QUADAS limitation: withdrawals from study not clearly explained.

d QUADAS limitation: execution of index test and reference standard not described in sufficient detail.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this systematic review was to evaluate monofilament testing with the 5.07/10-g monofilament as a diagnostic test for peripheral neuropathy of the feet of any cause. An effective diagnostic test requires an acceptable and well-established sensitivity and an acceptable specificity. Sensitivity in the included studies ranged from 41% to 93%, and specificity ranged from 68% to 100%. These wide ranges are possibly due to differences in application of the monofilament (number and site), interpretation of the monofilament test (definition of thresholds), and differences in study populations. A meta-analysis was not possible because of this clinical heterogeneity.

We believe our identification of studies has been complete, as we applied no language restriction and conducted a sensitive search. The study with the best characteristics (Lee et al14) showed a possibly serious methodological flaw: it was unclear whether the interpretation of the monofilament test was influenced by knowledge of the results of the reference standard and vice versa. In addition, a study population of 37 patients is quite small.

Another problem is the lack of standardization of the monofilament test methods. Different methods are described varying from 1 testing site15,16 to 10 testing sites14 on 1 foot, and there is no evidence or consensus about the most appropriate threshold.

We found various published reference standards for peripheral polyneuropathy, including clinical examination, vibration perception thresholds with biothesiometer/vibrameter/tuning forks, warm/cold detection, and nerve conduction studies. We rejected clinical examination, vibration perception, and warm/cold detection as reference standards: the first 2 because of obvious limitations in sensitivity or specificity,4,17,18 and thermal sense detection because it tests small-fiber neuropathy, whereas applying a monofilament and light touch, such as vibration and nerve conduction, tests for large-fiber neuropathy. Only 4 studies assessed with QUADAS used nerve conduction as the reference standard,14,15,19,20 of which 3 were included in our final selection.

We also rejected studies if the monofilament test was performed on patients who had visible ulcers. In patients with current visible ulcers, the interpretation of the monofilament test and the nerve conduction studies may be influenced by this knowledge (observer or reviewer bias).

We conclude that despite of the frequent use of the (Semmes-Weinstein) monofilament test, little can be said about the test accuracy for detecting neuropathy in feet that do not have visible ulcers, because diagnostic studies with adequate methodology are lacking. Further research on monofilament testing should focus on optimal standard test application procedures (number and sites) and on defining a reproducible threshold.

As this test is already widely used and advocated in many clinical guidelines, especially for diabetic patients, standardization of the method for the mono-filament test and studies to define the sensitivity of this method in clinical practice are important. Meanwhile, the sole use of a monofilament test to diagnose peripheral neuropathy is not recommended. The diagnosis of peripheral neuropathy can be made only after a careful clinical examination with more than 1 test, as recommended by the American Diabetes Association.1 Tests for this clinical examination are vibration perception (using a 128-Hz tuning fork), pressure sensation (using a 10-g monofilament at least at the distal halluces), ankle reflexes, and pinprick.1,2,21 When in doubt, a nerve conduction test might be necessary to establish a firm diagnosis.

Conflicts of interest: none reported

Funding support: The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) (4200.0018) supported this work, but it had no role in the design of the study; data collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or approval of publication of the finished manuscript.

Disclaimer: This article does not serve as an endorsement for any particular manufacturer of (Semmes-Weinstein) monofilaments.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2008. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(Suppl 1):S12–S54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boulton AJ, Vinik AI, Arezzo JC, et al.; American Diabetes Association. Diabetic neuropathies: a statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(4):956–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dyck PJ, Kratz KM, Karnes JL, et al. The prevalence by staged severity of various types of diabetic neuropathy, retinopathy, and nephropathy in a population-based cohort: the Rochester Diabetic Neuropathy Study. Neurology. 1993;43(4):817–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.England JD, Gronseth GS, Franklin G, et al. Distal symmetric polyneuropathy: a definition for clinical research: report of the American Academy of Neurology, the American Association of Electrodiagnostic Medicine, and the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Neurology. 2005;64(2):199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dutch Association of Neurology (NVN), Dutch Association of Clinical Neurophysiology (NVKNF). Guideline Polyneuropathy of the Dutch Institute for Healthcare Improvement (CBO). Alphen a/d Rijn, the Netherlands: van Zuiden; 2005.

- 6.NHS National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE). Type 2 Diabetes Prevention and Management of Foot Problems, Clinical Guideline 10. London, UK: National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE); 2004.

- 7.Abbott CA, Carrington AL, Ashe H, et al. The North-West Diabetes Foot Care Study: incidence of, and risk factors for, new diabetic foot ulceration in a community-based patient cohort. Diabet Med. 2002;19(5):377–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mueller MJ. Identifying patients with diabetes mellitus who are at risk for lower-extremity complications: use of Semmes-Weinstein monofilaments. Phys Ther. 1996;76(1):68–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valk GD, de Sonnaville JJ, van Houtum WH, et al. The assessment of diabetic polyneuropathy in daily clinical practice: reproducibility and validity of Semmes Weinstein monofilaments examination and clinical neurological examination. Muscle Nerve. 1997;20(1):116–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Birke JA, Sims DS. Plantar sensory threshold in the ulcerative foot. Lepr Rev. 1986;57(3):261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holewski JJ, Stess RM, Graf PM, Grunfeld C. Aesthesiometry: quantification of cutaneous pressure sensation in diabetic peripheral neuropathy. J Rehabil Res Dev. 1988;25(2):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh N, Armstrong DG, Lipsky BA. Preventing foot ulcers in patients with diabetes. JAMA. 2005;293(2):217–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whiting P, Rutjes AW, Dinnes J, Reitsma J, Bossuyt PM, Kleijnen J. Development and validation of methods for assessing the quality of diagnostic accuracy studies. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8(25: iii):59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee S, Kim H, Choi S, Park Y, Kim Y, Cho B. Clinical usefulness of the two-site Semmes-Weinstein monofilament test for detecting diabetic peripheral neuropathy. J Korean Med Sci. 2003;18(1):103–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perkins BA, Olaleye D, Zinman B, Bril V. Simple screening tests for peripheral neuropathy in the diabetes clinic. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(2):250–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rahman M, Griffin SJ, Rathmann W, Wareham NJ. How should peripheral neuropathy be assessed in people with diabetes in primary care? A population-based comparison of four measures. Diabet Med. 2003;20(5):368–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franse LV, Valk GD, Dekker JH, Heine RJ, van Eijk JT. ‘Numbness of the feet’ is a poor indicator for polyneuropathy in Type 2 diabetic patients. Diabet Med. 2000;17(2):105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamei N, Yamane K, Nakanishi S, et al. Effectiveness of Semmes-Weinstein monofilament examination for diabetic peripheral neuropathy screening. J Diabetes Complications. 2005;19(1):47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shin JB, Seong YJ, Lee HJ, Kim SH, Park JR. Foot screening technique in a diabetic population. J Korean Med Sci. 2000;15(1):78–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Brakel WH, Nicholls PG, Das L, et al. The INFIR Cohort Study: assessment of sensory and motor neuropathy in leprosy at baseline. Lepr Rev. 2005;76(4):277–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meijer JW, Smit AJ, Lefrandt JD, van der Hoeven JH, Hoogenberg K, Links TP. Back to basics in diagnosing diabetic polyneuropathy with the tuning fork! Diabetes Care. 2005;28(9):2201–2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]