Abstract

Context: Different menopausal hormone therapies may have varied effects on specific cognitive functions. We previously reported that conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) with medroxyprogesterone acetate had a negative impact on verbal memory but tended to impact figural memory positively over time in older postmenopausal women.

Objective: The objective of the study was to determine the effects of unopposed CEE on changes in domain-specific cognitive function and affect in older postmenopausal women with prior hysterectomy.

Design: This was a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial.

Setting: The study was conducted at 14 of 40 Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) clinical centers.

Participants: Participants were 886 postmenopausal women with prior hysterectomy, aged 65 yr and older (mean 74 yr), free of probable dementia, and enrolled in the WHI and WHI Memory Study (WHIMS) CEE-Alone trial for a mean of 3 yr and followed up for a mean of 2.70 yr.

Intervention: Intervention was 0.625 mg of CEE daily or placebo.

Main Outcome Measures: Annual rates of change in specific cognitive functions and affect, adjusted for time since randomization, were measured.

Results: Compared with placebo, unopposed CEE was associated with lower spatial rotational ability (P < 0.01) at initial assessment (after 3 yr of treatment), a difference that diminished over 2.7 yr of continued treatment. CEE did not significantly influence change in other cognitive functions and affect.

Conclusions: CEE did not improve cognitive functioning in postmenopausal women with prior hysterectomy. CEE was associated with lower spatial rotational performance after an average of 3 yr of treatment. Overall, CEE does not appear to have enduring effects on rates of domain-specific cognitive change in older postmenopausal women.

Conjugated equine estrogen does not appear to have enduring effects on domain-specific cognitive changes over time in older postmenopausal women with prior hysterectomy, indicating an overall lack of benefit or harm to specific cognitive functions.

Results from the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS) indicated an increased risk of dementia (1,2) and poorer performance on a measure of global cognition (3,4) in postmenopausal women aged 65 yr and older who had been randomized to receive combination hormone therapy containing conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) and medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) or CEE only compared with placebo. A subsample of 2305 WHIMS participants also received a more detailed annual cognitive evaluation through the Women’s Health Initiative Study of Cognitive Aging (WHISCA) to assess the effects of hormone treatment on domain-specific cognitive function (5).

The assessment of specific cognitive domains is particularly important for investigations of the effects of hormones on cognitive function because prior research indicates that only some aspects of cognition, e.g. verbal memory, figural memory, and speeded attention (6,7), may be sensitive to the effects of hormone therapy (HT). We previously reported that CEE+MPA had a deleterious effect on verbal memory and tended to have a positive effect on figural memory, but this treatment did not significantly influence other cognitive domains or affect in WHISCA participants enrolled in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) CEE+MPA trial (8). However, these findings reflect effects of the progestin, MPA, in addition to those of CEE. In the present report, we investigate the effects of CEE only on specific cognitive domains and affect in 886 WHIMS participants with prior hysterectomy who were randomized to receive unopposed CEE, i.e. with no progestin, vs. placebo in the WHI randomized Estrogen (CEE)-Alone trial. We compared these findings with those for the 1416 women in the CEE+MPA trial and present pooled results across the CEE-Alone and CEE+MPA trials. Our primary objective was to determine whether CEE only or CEE+MPA would protect against age-related declines in verbal and figural memory, as suggested by our observational findings from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (9,10). A secondary objective was to compare scores at initial WHISCA assessment to examine whether domain-specific cognitive function may have been differentially affected during the time period between initiation of HT and WHISCA enrollment.

Subjects and Methods

The WHISCA design, including recruitment of participants, test battery and rationale, training of testers, scoring, quality control, and data management procedures, is detailed elsewhere (5) and summarized below.

Participants

Procedures for enrollment and baseline sample characteristics for WHI (11) and WHIMS (12) and the subsamples in the CEE-Alone trial (1,13) have been described. This paper includes on-trial follow-up data through March 1, 2004, when the National Institutes of Health terminated study pills for the CEE-Alone trial due to an increased risk for stroke in women receiving CEE, with no benefit to coronary heart disease, the primary outcome (14). WHISCA participants were recruited from 14 of 39 WHIMS sites starting in October 1999. In addition to the major exclusions for WHI and WHIMS, participants were eligible for WHISCA if they were English speaking and did not have probable dementia, as determined by the WHIMS protocol (1). All participants provided written informed consent. The WHISCA protocol was approved by institutional review boards at each clinic site, the clinical coordinating center, and the National Institute on Aging.

Hormone treatment

Randomized assignment to treatment was performed through the WHI Hormone Therapy Trials protocol. Women with prior hysterectomy were randomly assigned to take one daily tablet containing CEE, 0.625 mg (Premarin; Wyeth Pharmaceuticals) or a matching placebo (also provided by Wyeth Pharmaceuticals). Because WHISCA was initiated after WHI randomization, women had received treatment for 1.1–5.6 yr (mean 3.0) before WHISCA initial assessment.

Tests of cognition and affect

The WHISCA test battery (Table 1) was designed to test a broad range of specific cognitive functions and affect, emphasizing tests that are sensitive to longitudinal age changes or effects of hormones and has been described previously (5,8). Measures of verbal and figural memory were expected to show the greatest sensitivity to HT.

Table 1.

Summary of test measures and outcome variables

| Cognitive/affective domain and measure | Outcome variable | Score range | Predicted treatment effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Verbal knowledge | Total correct−one third number | ≤50 | |

| PMA vocabulary | incorrect | No difference | |

| Verbal fluency | No difference | ||

| Letter fluency (F, A, S) | Total correct | 0+ | |

| Semantic fluency (vegetables, fruits) | Total correct | 0+ | |

| Figural memory | Total figures with errors | 0–26 | CEE fewer errors over time |

| BVRT | |||

| Verbal memory | Total of 3 list A trials (immediate recall) | 0–48 | CEE higher scores over time |

| CVLT | Total for list B (interference) | 0–16 | |

| Total for short-delay free recall | 0–16 | ||

| Total for long-delay free recall | 0–16 | ||

| Attention and working memory | CEE higher scores over time | ||

| Digits forward | Total correct trials | 0–14 | |

| Digits backward | Total correct trials | 0–14 | |

| Spatial rotational ability | Total correct−total incorrect | ≤160 | CEE lower over time |

| Card rotations | |||

| Fine motor speed | CEE higher scores over time | ||

| Finger tapping dom | Total score | 0+ | |

| Finger tapping nondom | Total score | 0+ | |

| Affect | |||

| PANAS | |||

| PANAS positive | Mean score | 1–5 | |

| PANAS negative | Mean score | 1–5 | CEE lower over time |

| Geriatric depression scale | Total score | 0–15 | CEE lower over time |

Descriptions and references for tests of cognition and affect are detailed elsewhere (5). Higher BVRT scores reflect poorer performance. Tests in bold are those predicted to be the most sensitive to treatment effects based on prior studies. PMA, Primary mental abilities; BVRT, Benton Visual Retention Test; CVLT, California Verbal Learning Test; dom, dominant hand; nondom, nondominant hand; PANAS, Positive and Negative Affect Schedule.

Test procedures

Assessments of cognitive function and affect were conducted annually for WHISCA participants. The same test battery was administered at each assessment, with the exception of the California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT), which used two alternate forms according to the following schedule: assessments 1 and 2, form A; assessments 3 and 4, form B; assessment 5, form A (15). Testing procedures were consistent with those in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (16), except three rather than five learning trials were used on the CVLT. Test administrators were trained centrally and quality control was maintained through the WHISCA clinical coordinating center at Wake Forest University.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted using SAS (version 9.1; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Differences between WHISCA women randomized to CEE only vs. placebo with respect to demographic characteristics at the time of WHI enrollment were determined using χ2 tests and t tests. Analyses were repeated for participants who completed four WHISCA assessments before March 1, 2004.

The principal WHISCA outcome measures are the mean rates of change across follow-up for tests of specific cognitive functions and affect. Linear mixed models were used to estimate the difference in the mean rate of change (slope) for women grouped by treatment assignment. Covariates included visit number and time from WHI randomization to WHISCA enrollment. We also examined mean differences between treatment groups at the time of enrollment into WHISCA, using analyses of covariance to adjust for time since randomization. To control type I error across the multiple outcome measures, a two-sided 0.01 critical level for statistical significance was specified a priori by the WHISCA protocol; a strict Bonferroni adjustment was considered overly conservative due to correlations among outcomes.

Consistent with our approach to the CEE+MPA trial, we conducted several supporting secondary analyses. We examined the impact of treatment assignment on women free of selected clinically detectable disease throughout the trial by repeating analyses for participants who remained free of probable dementia, mild cognitive impairment, and stroke throughout the trial. The same analyses were performed for the subgroup completing four follow-up visits before termination of study medications. To examine the impact of treatment adherence, we repeated the intention-to-treat analyses after excluding test scores from visits after which participants became nonadherent by WHI criteria: 1) stopped study pills (dropouts), 2) took fewer than 80% of study pills between dispensation and collection, or 3) began prescription hormones outside the main WHI trials (drop-ins). Analyses also were repeated adjusting for global cognition score, as measured by the Modified Mini-Mental State Exam (3MS) (17), at WHIMS baseline, to control for variability in global cognition at the time of WHIMS enrollment. Subgroup analyses also were conducted on WHI baseline factors, including age and baseline 3MS score, thought to influence either test scores or the impact of CEE treatment. Finally, we performed a pooled analysis of the CEE-Alone and CEE+MPA trials, adjusting for time from WHI enrollment to WHISCA randomization, as specified by the original WHISCA protocol, to determine whether HT generally influenced domain-specific cognitive function and affect.

Results

Participant characteristics

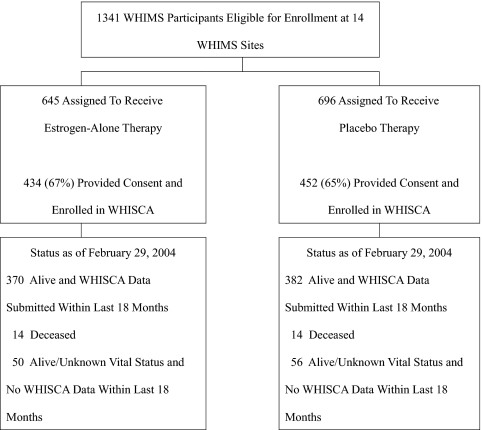

Of 1361 CEE-Alone trial participants eligible for WHISCA, 886 (65%) agreed to participate. Compared with WHIMS CEE-Alone trial women who did not enroll in WHISCA at the same clinics, those who joined WHISCA tended to be younger (P = 0.03) and better educated (P = 0.003), had never smoked (P = 0.003), had previously used HT (P = 0.05), and were more likely to have 3MS scores greater than 95 (P < 0.001). They did not differ significantly with respect to use of aspirin, alcohol, or statins; prevalence of diabetes, heart disease, or hypertension; body mass index; family income; race/ethnicity; or age of menopause. Characteristics of WHISCA participants in both treatment groups at WHI and WHISCA initial assessments are shown in Table 2, and the WHISCA sample profile is summarized in Fig. 1. The numbers of participants completing first through fourth annual assessments, respectively, before WHI termination of study medications were: 434, 412 (94.9%), 391 (90.1%), and 326 (75.1%) for the CEE-only group and 452, 408 (90.3%), 388 (85.8%), and 325 (71.9%) for the placebo group. WHISCA participants completed a mean (sd) of 3.7 (0.9) visits (range 1–6). The mean (sd) follow-up intervals from the initial WHISCA assessment to the last on-trial assessment were 2.70 (0.91) yr for the entire sample, 2.75 (0.85) yr for the CEE-only group, and 2.65 (0.96) yr for the placebo group.

Table 2.

Characteristics of WHISCA CEE sample at WHI baseline by treatment assignment, including age and 3MS score at WHISCA initial assessment and time from randomization

| Variable | CEE | Placebo | Test of homogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at WHISCA initial assessment, mean (sd), yr | 74.01 (3.73) | 74.02 (3.92) | 0.988 |

| Time from WHI randomization to WHISCA initial assessment, mean (sd), yr | 3.02 (0.70) | 3.01 (0.67) | 0.841 |

| 3MS total score at WHI enrollment | 95.13 (3.88) | 95.49 (4.00) | 0.506 |

| 3MS total score at WHISCA enrollment | 95.35 (3.89) | 95.49 (4.00) | 0.596 |

| Education, n (%) | 0.809 | ||

| Less than high school | 26 (6.00) | 27 (5.99) | |

| High school/GED | 115 (26.56) | 107 (23.73) | |

| >High school, less than 4 yr college | 176 (40.65) | 191 (42.35) | |

| 4 yr or more of college | 116 (26.79) | 126 (27.94) | |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | 0.662 | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 372 (85.91) | 392 (86.92) | |

| Nonwhite/other | 61 (14.09) | 59 (13.08) | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean (sd) | 29.40 (6.23) | 29.21 (5.60) | 0.644 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | 0.031 | ||

| Never | 257 (59.77) | 244 (54.46) | |

| Former | 157 (36.51) | 170 (37.95) | |

| Current | 16 (3.72) | 34 (7.59) | |

| Alcoholic drinks per week, n (%) | 0.098 | ||

| 0 | 211 (48.62) | 225 (50.00) | |

| 1–6 | 189 (43.55) | 173 (38.44) | |

| 7+ | 34 (7.83) | 52 (11.56) | |

| Prior CVD, n (%) | 0.722 | ||

| No | 384 (88.48) | 395 (87.39) | |

| History of stroke | 5 (1.15) | 8 (1.77) | |

| History of other CVD | 45 (10.37) | 49 (10.84) | |

| Hypertension at WHI baseline, n (%), no/yes | 201 (46.31)/233 (53.69) | 221 (48.89)/231 (51.11) | 0.442 |

| Diabetes, n (%), no/yes | 390 (89.86)/44 (10.14) | 403 (89.16)/49 (10.84) | 0.733 |

| Moderate/severe vasomotor symptoms, n (%), no/yes | 391 (90.72)/40 (9.28) | 407 (90.44)/43 (9.56) | 0.889 |

| Prior hormone therapy, n (%) | |||

| Any prior use | 215 (49.54) | 209 (46.24) | 0.326 |

| Among those with prior use: duration less than 10 yr | 134 (62.33) | 140 (66.99) | 0.316 |

CVD, Cardiovascular disease.

Figure 1.

Profile of the estrogen-alone component of WHISCA.

Demographic and health-related characteristics of treatment groups

WHISCA CEE-only and placebo groups did not differ significantly at WHI baseline for demographic and health-related characteristics or for global cognitive function (Table 2; all P > 0.05) except that more CEE-only participants had never smoked (P = 0.03). Groups also did not differ significantly in mean 3MS scores at WHISCA initial assessment [mean (sd)]: CEE-only, 95.35 (3.89); placebo, 95.49 (4.00) (P = 0.51). Treatment groups were also comparable with respect to body mass index, alcohol intake, and antihypertensive use at WHI enrollment and numbers of incident cases of diabetes and myocardial infarction since randomization (P > 0.05). Comparisons of subgroups completing four WHISCA assessments before March 1, 2004, showed that treatment groups remained comparable and did not differ significantly on demographic and health-related measures. A slightly lower percentage of women met the WHI criteria for adherence in the CEE-only vs. placebo group, but the difference was not statistically significant except in the second year follow-up: initial WHISCA assessment, CEE, 278 of 434 (64.1%), placebo, 303 of 452 (67.0%), P = 0.35; 1-yr follow-up, CEE, 233 of 412 (56.6%), placebo, 259 of 408 (63.5%), P = 0.04; 2-yr follow-up, CEE, 201 of 391 (51.4%), placebo, 219 of 388 (56.4%), P = 0.16; 3-yr follow-up, CEE, 162 of 326 (49.7%), placebo, 173 of 325 (53.2%), P = 0.37.

Effects of CEE only

After enrollment in WHISCA, six participants were diagnosed with probable dementia (four CEE, two placebo), 33 with mild cognitive impairment (18 CEE, 15 placebo), and 18 with incident strokes (eight CEE, 10 placebo).

Mean unadjusted scores and sds for the cognitive outcome measures are presented by treatment group and visit in Table 3. Results of the primary analyses are summarized in Table 4 for the intention-to-treat sample. Across both treatment groups, analysis of longitudinal changes indicated overall improvements in cognitive performance over time, with the exception of digits forward, digits backward, and finger tapping nondominant hand. Positive affect and negative affect scores did not change over time, and there were small, nonsignificant increases in depressive symptom scores over time across both treatment groups. Mean differences between treatment groups at the initial WHISCA assessment, adjusted for time since randomization, are shown in the left column of Table 4, with positive values indicating higher scores for the CEE compared with placebo group. Only the card rotations test showed significantly lower performance in women randomized to CEE compared with placebo (P = 0.005). However, trends toward lower performance in the CEE compared with placebo group were observed across a number of measures. Results were similar in analyses excluding individuals with probable dementia, mild cognitive impairment, and stroke.

Table 3.

Mean (se) adjusted scores for cognitive and affective measures by treatment group for the intention-to-treat sample

| Measure | Visit 1

|

Visit 2

|

Visit 3

|

Visit 4

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEE | Placebo | CEE | Placebo | CEE | Placebo | CEE | Placebo | |

| Number of subjects | 434 | 452 | 412 | 408 | 391 | 388 | 326 | 325 |

| Verbal knowledge | ||||||||

| PMA vocabulary | 34.73 (0.48) | 35.88 (0.47) | 35.81 (0.48) | 36.50 (0.47) | 35.77 (0.49) | 36.76 (0.48) | 35.94 (0.49) | 36.60 (0.49) |

| Verbal fluency | ||||||||

| Letter fluency | 38.40 (0.61) | 39.57 (0.60) | 39.74 (0.62) | 40.58 (0.61) | 39.15 (0.62) | 40.84 (0.61) | 39.31 (0.64) | 41.17 (0.63) |

| Category fluency | 28.13 (0.30) | 28.94 (0.30) | 28.21 (0.31) | 28.75 (0.31) | 27.42 (0.31) | 28.09 (0.31) | 27.20 (0.32) | 27.99 (0.32) |

| Memory | ||||||||

| BVRT errors | 7.73 (0.19) | 7.35 (0.19) | 7.45 (0.19) | 7.28 (0.19) | 7.29 (0.20) | 6.89 (0.19) | 7.67 (0.20) | 7.04 (0.20) |

| CVLT | ||||||||

| Total list A trials | 27.78 (0.31) | 28.40 (0.31) | 28.74 (0.32) | 28.84 (0.31) | 24.70 (0.32) | 25.33 (0.32) | 25.29 (0.34) | 26.70 (0.34) |

| Total list B interference trial | 6.34 (0.09) | 6.43 (0.09) | 6.35 (0.10) | 6.65 (0.10) | 4.50 (0.10) | 4.73 (0.10) | 4.51 (0.11) | 4.70 (0.11) |

| Short delay free | 8.16 (0.15) | 8.16 (0.15) | 8.64 (0.16) | 8.49 (0.15) | 7.40 (0.16) | 7.47 (0.16) | 7.72 (0.17) | 7.95 (0.16) |

| Long delay free | 8.89 (0.15) | 8.93 (0.15) | 9.25 (0.16) | 9.26 (0.15) | 8.67 (0.16) | 8.72 (0.16) | 8.81 (0.17) | 9.15 (0.17) |

| Attention and working memory | ||||||||

| Digits forward | 7.21 (0.10) | 7.42 (0.10) | 7.38 (0.10) | 7.51 (0.10) | 7.48 (0.10) | 7.48 (0.10) | 7.34 (0.11) | 7.42 (0.11) |

| Digits backward | 6.49 (0.09) | 6.53 (0.09) | 6.34 (0.10) | 6.41 (0.09) | 6.34 (0.10) | 6.45 (0.10) | 6.30 (0.10) | 6.43 (0.10) |

| Spatial ability | ||||||||

| Card rotations | 51.33 (1.39) | 56.66 (1.36) | 54.90 (1.41) | 60.57 (1.39) | 58.30 (1.42) | 60.08 (1.40) | 60.65 (1.47) | 63.53 (1.45) |

| Fine motor speed | ||||||||

| Finger tapping dom | 37.67 (0.34) | 38.71 (0.33) | 38.52 (0.35) | 39.66 (0.34) | 38.93 (0.35) | 39.89 (0.35) | 38.75 (0.37) | 39.93 (0.36) |

| Finger tapping nondom | 35.64 (0.29) | 36.28 (0.29) | 35.89 (0.30) | 36.85 (0.29) | 35.96 (0.30) | 36.90 (0.30) | 35.84 (0.31) | 36.88 (0.31) |

| Affect | ||||||||

| PANAS positive | 3.61 (0.03) | 3.66 (0.03) | 3.63 (0.03) | 3.61 (0.03) | 3.58 (0.03) | 3.63 (0.03) | 3.63 (0.04) | 3.63 (0.04) |

| PANAS negative | 1.64 (0.03) | 1.64 (0.03) | 1.67 (0.03) | 1.67 (0.03) | 1.64 (0.03) | 1.68 (0.03) | 1.66 (0.04) | 1.67 (0.03) |

| GDS | 1.58 (0.11) | 1.74 (0.11) | 1.71 (0.12) | 1.93 (0.11) | 1.64 (0.12) | 1.91 (0.12) | 1.62 (0.12) | 2.00 (0.12) |

The CEE-only compared with placebo group had significantly lower overall scores for card rotations (P < 0.01) and finger tapping dominant hand (P = 0.01). Statistical analysis of treatment effects at initial assessment and change over time are presented in Table 4. Higher BVRT scores reflect poorer performance. Lower CVLT scores at visits 3 and 4 are due to lower mean scores on CVLT version B compared with version A. PMA, Primary mental abilities; dom, dominant hand; nondom, nondominant hand; PANAS, Positive and Negative Affect Schedule; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale.

Table 4.

Differences in primary outcomes between CEE-Alone and placebo at WHISCA enrollment and over follow-up, adjusted for time since randomization

| Measure | Difference (CEE only minus placebo) at initial WHISCA assessment

|

Overall changes with time

|

Difference (CEE only minus placebo): on-study rates of change (units/yr)

|

Difference (CEE only minus placebo): on-study rates of change (units/yr) for subgroup with four visits

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (se) | P value | P value | Mean (se) | P value | Mean (se) | P value | |

| Verbal knowledge | |||||||

| PMA vocabulary | −1.11 (0.67) | 0.098 | <0.0001 | 0.11 (0.11) | 0.326 | 0.10 (0.14) | 0.493 |

| Verbal fluency | |||||||

| Letter fluency | −1.17 (0.83) | 0.162 | <0.0001 | −0.26 (0.19) | 0.175 | −0.36 (0.25) | 0.152 |

| Category fluency | −0.81 (0.42) | 0.057 | <0.0001 | 0.03 (0.11) | 0.760 | −0.04 (0.14) | 0.765 |

| Memory | |||||||

| BVRT errors | 0.38 (0.26) | 0.151 | 0.008 | 0.11 (0.07) | 0.115 | 0.08 (0.08) | 0.318 |

| CVLT total list A trials | −0.62 (0.42) | 0.144 | −0.19 (0.14) | 0.174 | −0.40 (0.17) | 0.022 | |

| CVLT total list B | −0.09 (0.14) | 0.521 | −0.06 (0.05) | 0.296 | −0.02 (0.07) | 0.757 | |

| CVLT short delay free | −0.00 (0.21) | 0.979 | −0.08 (0.07) | 0.234 | −0.16 (0.08) | 0.054 | |

| CVLT long delay free | −0.04 (0.20) | 0.840 | −0.08 (0.07) | 0.242 | −0.19 (0.08) | 0.027 | |

| Attention and working memory | |||||||

| Digits forward | −0.21 (0.13) | 0.118 | 0.337 | 0.03 (0.04) | 0.396 | 0.04 (0.05) | 0.480 |

| Digits backward | −0.04 (0.14) | 0.780 | 0.061 | −0.05 (0.04) | 0.170 | −0.07 (0.05) | 0.171 |

| Spatial ability | |||||||

| Card rotations | −5.28 (1.87) | 0.005 | <0.0001 | 1.26 (0.48) | 0.008 | 1.41 (0.60) | 0.019 |

| Fine motor speed | |||||||

| Finger tapping dom | −1.12 (0.51) | 0.028 | <0.0001 | −0.01 (0.15) | 0.942 | 0.03 (0.18) | 0.879 |

| Finger tapping nondom | −0.59 (0.44) | 0.178 | 0.055 | −0.10 (0.12) | 0.360 | −0.03 (0.14) | 0.830 |

| Affect | |||||||

| PANAS positive | −0.04 (0.05) | 0.335 | 0.353 | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.479 | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.541 |

| PANAS negative | −0.00 (0.04) | 0.907 | 0.381 | −0.01 (0.01) | 0.455 | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.739 |

| GDS | −0.16 (0.16) | 0.306 | 0.034 | −0.08 (0.05) | 0.116 | −0.06 (0.06) | 0.339 |

| 3MS score | −0.42 (0.22) | 0.060 | 0.349 | 0.08 (0.08) | 0.327 | 0.09 (0.10) | 0.332 |

Positive values indicate higher scores (initial assessment) and lower rates of decline for the CEE compared with placebo group; significant overall changes with time indicate significant improvements in performance over time. Higher BVRT scores reflect poorer performance. PMA, Primary mental abilities; dom, dominant hand; nondom, nondominant hand; PANAS, Positive and Negative Affect Schedule; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale.

The primary outcome measures, differences in rates of change during WHISCA follow-up between treatment groups, adjusted for time since randomization, are shown in the middle columns of Table 4 for all participants and in the right columns for women completing four visits. Positive values indicate greater longitudinal increases or smaller decreases in scores for the CEE-only compared with placebo group and negative values indicate greater longitudinal increases or smaller decreases for the placebo group. [Note that the Benton Visual Retention Test (BVRT) scores reflect errors rather than correct responses.] Only card rotations scores showed significantly different treatment effects on rate of change. Women randomized to CEE only showed significantly greater improvements in card rotations scores over time relative to placebo (P < 0.01), although both groups showed improved performance from initial to subsequent assessments. Rates of change for other cognitive measures and affect did not differ significantly between treatment groups. In secondary analyses restricted to women who had completed four visits (last columns in Table 4), trends toward lower performance over time for the CEE compared with placebo group were observed for CVLT immediate recall over three trials and long-delay free recall, and the CEE group showed a trend toward greater improvement over time on the card rotations test (P < 0.05).

Results remained similar in secondary analyses after excluding participants with probable dementia, mild cognitive impairment, and stroke and after adjustment for 3MS score at WHI enrollment. In analyses restricted to women meeting the WHI criterion for adherence, no tests reached the 0.01 significance level.

Table 5 summarizes the results of the CEE-Alone, CEE+MPA, and both trials pooled for the WHISCA initial assessment and annual rates of change during the on-trial follow-up periods. Across both trials combined, only digits forward showed a significant adverse effect of HT at initial WHISCA assessment (P < 0.01). CVLT immediate recall, short-delay, and long-delay free recall showed trends toward adverse effects of HT on longitudinal rates of change over time for the combined trials, predominantly due to the adverse effect of HT in the CEE+MPA trial.

Table 5.

Summary of effect sizes in the WHISCA CEE-Alone trial, CEE+MPA trial, and pooled analysis

| Measure | Difference (HT minus placebo) at initial WHISCA assessment

|

Difference (HT minus placebo): on-study rates of change (units/yr)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEE only mean (se) | CEE+MPA mean (se) | HT pooled mean (se) | CEE only mean (se) | CEE+MPA mean (se) | HT pooled mean (se) | |

| Verbal knowledge | ||||||

| PMA vocabulary | −1.11 (0.67) | −0.35 (0.51) | −0.66 (0.41) | 0.11 (0.11) | −0.10 (0.17) | 0.04 (0.10) |

| Verbal fluency | ||||||

| Letter fluency | −1.17 (0.83) | 0.23 (0.66) | −0.31 (0.52) | −0.26 (0.19) | −0.28 (0.29) | −0.29 (0.16) |

| Category fluency | −0.81 (0.42) | −0.14 (0.33) | −0.41 (0.26) | 0.03 (0.11) | −0.09 (0.19) | −0.01 (0.10) |

| Memory | ||||||

| BVRT errors | 0.38 (0.26) | 0.11 (0.20) | 0.20 (0.16) | 0.11 (0.07) | −0.27 (0.11)a | 0.00 (0.06) |

| CVLT total list A trials | −0.62 (0.42) | 0.23 (0.34) | −0.10 (0.26) | −0.19 (0.14) | −0.52 (0.20)b | −0.28 (0.12)a |

| CVLT total list B | −0.09 (0.14) | −0.06 (0.11) | −0.07 (0.09) | −0.06 (0.05) | 0.05 (0.08) | −0.03 (0.04) |

| CVLT short delay free | −0.01 (0.21) | 0.19 (0.16) | 0.11 (0.13) | −0.08 (0.07) | −0.24 (0.10)a | −0.13 (0.06)a |

| CVLT long delay free | −0.04 (0.20) | 0.15 (0.16) | 0.07 (0.13) | −0.08 (0.07) | −0.23 (0.10)a | −0.13 (0.06)a |

| Attention and working memory | ||||||

| Digits forward | −0.21 (0.13) | −0.22 (0.11)a | −0.22 (0.09)b | 0.03 (0.04) | 0.06 (0.06) | 0.04 (0.03) |

| Digits backward | −0.03 (0.14) | −0.19 (0.11) | −0.13 (0.08) | −0.05 (0.04) | 0.08 (0.06) | −0.01 (0.03) |

| Spatial ability | ||||||

| Card rotations | −5.28 (1.87)b | 1.07 (1.44) | −1.36 (1.14) | 1.26 (0.48)b | −0.39 (0.70) | 0.67 (0.39) |

| Fine motor speed | ||||||

| Finger tapping dom | −1.12 (0.51) | 0.10 (0.42) | −0.35 (0.32) | −0.01 (0.15) | 0.00 (0.21) | −0.06 (0.12) |

| Finger tapping nondom | −0.59 (0.44) | 0.11 (0.35) | −0.14 (0.27) | −0.10 (0.12) | 0.02 (0.17) | −0.10 (0.10) |

| Affect | ||||||

| PANAS positive | −0.04 (0.05) | 0.02 (0.03) | −0.00 (0.03) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.01 (0.01) |

| PANAS negative | −0.01 (0.04) | 0.01 (0.03) | 0.00 (0.03) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.02 (0.02) | −0.01 (0.01) |

| GDS | −0.16 (0.16) | −0.03 (0.11) | −0.08 (0.09) | −0.08 (0.05) | 0.04 (0.07) | −0.04 (0.05) |

| 3MS score | −0.42 (0.22) | −0.04 (0.17) | −0.14 (0.13) | 0.08 (0.08) | −0.14 (0.09) | 0.00 (0.06) |

Positive values indicate higher scores (initial assessment) and lower rates of decline for the HT compared with placebo groups; higher BVRT scores reflect poorer performance. PMA, Primary mental abilities; dom, dominant hand; nondom, nondominant hand; PANAS, Positive and Negative Affect Schedule; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

Discussion

Conclusions

In the present study, we compared WHISCA participants with prior hysterectomy who had been randomized to receive CEE only vs. placebo through the WHI clinical trials of menopausal HT. We found no evidence of a beneficial effect of CEE on verbal memory and found nonsignificant trends to adverse effects on immediate and delayed verbal recall performance of questionable clinical significance in analyses restricted to women with four visits. In addition, the CEE-only group performed worse than the placebo group at initial evaluation with the card rotations test, and although the CEE-only group improved more over the follow-up, their overall performance was lower than the placebo group. CEE did not affect other cognitive domains, including figural memory, or affect, indicating an overall lack of benefit or harm.

Based on prior findings of beneficial effects of estrogen-containing HT on verbal and figural memory in observational studies (9,10) and randomized trials of younger women after surgical menopause (18), we hypothesized a priori that women randomized to HT, with or without progestin, would show decreased longitudinal decline in memory compared with women receiving placebo. Since the initiation of the WHISCA study, these hypotheses have been challenged by findings from the WHIMS CEE-Alone and CEE+MPA trials and the WHISCA CEE+MPA study, which together showed increased risk of probable dementia (1,2), poorer global cognition (3,4), and reduced verbal memory (8) in women aged 65 yr and older who were randomized to HT. One explanation for the unexpected adverse effect of CEE+MPA on verbal memory performance in the WHISCA combined CEE+MPA trial was the use of MPA in addition to CEE. However, lack of beneficial effects of HT on memory performance in older postmenopausal women also has been reported in a number of smaller randomized trials using a variety of treatments, including CEE and trimonthly MPA (19), ultralow-dose estradiol (20,21), and 3-wk high-dose estradiol (22). Thus, studies using a variety of treatment regimens, involving both CEE and estradiol, fail to provide evidence of a benefit of HT when initiated in older postmenopausal women.

In addition to the lack of benefit of CEE only on age-related changes in memory, an important finding of the present study is that women randomized to CEE only, compared with placebo, had significantly lower scores on a measure of spatial rotational ability at WHISCA enrollment after an average of 3 yr of treatment but showed a greater rate of improvement in spatial rotational performance over time. Although their performance showed some improvement over time, possibly due to greater improvement with practice on this relatively novel task, lower spatial rotational performance has been associated with higher estrogen levels in studies of menstrual cycle variation in premenopausal women (23,24). Additionally, spatial tasks are dependent on right hemisphere function, and right hemisphere function decreases with higher estradiol in postmenopausal women (25). Moreover, in an observational study of older women using HT, women taking estrogens and progestins had higher spatial rotational performance compared with women taking unopposed estrogens (10). Combined, these findings and our observation that at initial assessment CEE but not CEE+MPA was associated with decreased card rotations performance, suggesting that MPA may protect against an estrogen-associated short-term reduction in spatial rotational ability. The possible effect of MPA, which may have weak androgenic in addition to progestogenic actions (26), on spatial ability may also explain our observation that CEE+MPA was associated with a trend toward beneficial effects on figural memory (8), whereas unopposed CEE did not significantly affect figural memory. Because androgens have been associated with increased spatial ability (27), it is possible that androgenic effects of MPA on the visuospatial aspects of the BVRT mediated the trend toward increased performance on the BVRT test of figural memory in the CEE+MPA trial.

A summary of results from the WHISCA CEE-Alone and CEE+MPA studies is shown in Table 5 along with results of the analysis of both WHI HT trials pooled. At initial WHISCA assessment, no cognitive outcomes reached the 0.01 significance level for the CEE+MPA trial, whereas card rotations performance was significantly lower in women randomized to CEE only vs. placebo at initial assessment and with respect to overall performance. In the CEE+MPA trial, women randomized to active treatment showed significantly greater decline in verbal memory over a 1.3-yr follow-up interval, but no significant differences in verbal memory were evident over the 2.7 yr follow-up in women randomized to CEE only vs. placebo. In contrast, card rotations performance did not differ over time in women randomized to CEE+MPA, whereas women randomized to CEE only compared with placebo showed greater increase over time in spatial rotational performance, consistent with some recovery of their initially poorer performance.

As specified in the original WHISCA protocol, a pooled analysis of HT effects on cognitive outcomes was performed across both trials combined. These results should be interpreted with caution, given significant demographic differences in women enrolled in the CEE-Alone and CEE+MPA WHI trials (28) and differences in the potential effects of these treatments on cognitive outcomes. In the pooled analysis, only digits forward, a measure of attention and immediate recall, showed significantly lower performance in women randomized to HT vs. placebo at initial enrollment after 3 yr of treatment. Although negative effects of HT on verbal memory over time were significant in the CEE+MPA trial, results in the pooled analysis did not reach the 0.01 level of significance. However, it is notable that both findings in these older postmenopausal women argue against the predicted benefit of HT, based on studies of verbal memory and attentional function in younger women (7).

Analogous to our WHISCA study of effects of CEE+MPA on cognitive function, a number of limitations should be considered in interpreting the results of our investigation of the effects of unopposed CEE on domain-specific cognitive function. Although WHISCA was conducted within the context of the WHI randomized trials of CEE+MPA and CEE-Alone, enrollment into WHISCA did not begin until 3 yr after WHI randomization. WHISCA participants were younger and better educated, scored higher on the 3MS, and were more likely to be prior users of HT compared with eligible women who chose not to participate. Because healthier women appear more resistant to adverse effects of HT (4,29), potential adverse effects of HT may be reduced in the WHISCA sample. Due to safety issues, all women in the CEE-Alone trial had prior hysterectomy. However, the CEE-only and its placebo group were comparable with respect to hysterectomy status and were well balanced at WHI and WHISCA initial assessments on demographic and health-related characteristics and global cognitive functioning. At the initial WHISCA assessment, only card rotations showed reduced performance in association with CEE only, but pretreatment scores for specific cognitive domains at WHI baseline were not determined. In addition, the early termination of the WHI CEE+MPA and CEE-Alone trials reduced the power available for detecting treatment effects in WHISCA. WHISCA was originally designed to provide greater than 90% power to detect 50% treatment effects (HT vs. placebo, pooled across trials) on the progression rates of individual cognitive declines, using benchmark data on the BVRT, with two-tailed type I error set at 0.01 for each comparison (5). Based on this approach and the ses observed for the BVRT, achieved power was approximately 60% for each domain in analyses pooled across trials and approximately 45% for each domain within the CEE-Alone trial.

The WHISCA studies were designed to test the effects of specific treatment regimens (CEE only and CEE+MPA) on longitudinal changes in domain-specific cognitive function in older postmenopausal women. The generality of our findings to other treatment regimens and other age groups is unknown. It is possible that earlier initiation of HT during the menopausal transition, as suggested by the window of opportunity theory, will have different effects and possible benefits to memory and other cognitive functions, providing reconciliation of results from clinical trials and observational studies.

Acknowledgments

Short list of WHISCA investigators included the following: National Institute of Aging program office, Alan Zonderman, Susan M. Resnick; WHISCA central coordinating center, Sally Shumaker, principal investigator; Stephen Rapp, Mark Espeland, Laura Coker, Deborah Farmer, Anita Hege, Patricia Hogan, Darrin Harris, Cynthia McQuellon, Anne Safrit, Lee Ann Andrews, Candace Warren, Carolyn Bell, Linda Allred. WHISCA clinical sites included: WHI (Durham, NC), Carol Murphy; (Rush Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Medical Center, Chicago, IL), Linda Powell; (Ohio State University Medical Center, Columbus, OH), Rebecca Jackson; (University of California at Davis, Sacramento, CA), John Robbins; (University of Iowa College of Medicine, Des Moines, IA), Robert Wallace; (University of Florida, Gainesville/Jacksonville, FL), Marian Limacher; (University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA), Howard Judd; (Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI), Jane Kotchen; (The Berman Center for Outcomes and Clinical Research, Minneapolis, MN), Karen Margolis; (University of Nevada School of Medicine, Reno, NV), Robert Brunner; (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY), Sylvia Smoller; (The Leland Stanford Junior University, San Jose, CA), Marcia Stefanick; (The State University of New York, Stony Brook, NY), Dorothy Lane; (University of Massachusetts/Fallon Clinic, Worcester, MA), Judith Ockene. The following investigators were the original investigators for these sites: Mary Haan, Davis, CA; Richard Grimm, Minneapolis, MN; Sandra Daugherty, deceased (Reno, NV). The WHI program office (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, MD) included Barbara Alving, Jacques Rossouw, Linda Pottern. The WHI central coordinating center investigators (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA) included Deborah Bowen, Gretchen VanLom, Carolyn Burns.

Footnotes

WHISCA is funded by the National Institute on Aging Contract N01-AG-9-2115 and is supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging. The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, through Contracts N01WH22110, 24152, 32100-2, 32105-6, 32108-9, 32111-13, 32115, 32118-32119, 32122, 42107-26, 42129-32, and 44221. The WHIMS study was funded in part by Wyeth Pharmaceuticals.

Current address for P.M.M.: University of Illinois, Chicago, Illinois.

Disclosure Summary: S.M.R., M.A.E., Y.A., L.H.C., R.J., M.L.S., R.W., and S.R.R. have nothing to disclose. P.M.M. received grant support from Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, honoraria from the North American Menopause Society and Contemporary Forums, and has received consultant fees as an advisor to the Council on Menopause Management.

First Published Online October 22, 2009

Abbreviations: BVRT, Benton Visual Retention Test; CEE, conjugated equine estrogens; CVLT, California Verbal Learning Test; HT, hormone therapy; MPA, medroxyprogesterone acetate; 3MS, Modified Mini-Mental State Exam; WHI, Women’s Health Initiative; WHIMS, WHI Memory Study; WHISCA, WHI Study of Cognitive Aging.

References

- Shumaker SA, Legault C, Rapp SR, Thal L, Wallace RB, Ockene JK, Hendrix SL, Jones 3rd BN, Assaf AR, Jackson RD, Kotchen JM, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Wactawski-Wende J 2003 Estrogen plus progestin and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 289:2651–2662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumaker SA, Legault C, Kuller L, Rapp SR, Thal L, Lane DS, Fillit H, Stefanick ML, Hendrix SL, Lewis CE, Masaki K, Coker LH 2004 Conjugated equine estrogens and incidence of probable dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study. JAMA 291:2947–2958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp SR, Espeland MA, Shumaker SA, Henderson VW, Brunner RL, Manson JE, Gass ML, Stefanick ML, Lane DS, Hays J, Johnson KC, Coker LH, Dailey M, Bowen D 2003 Effect of estrogen plus progestin on global cognitive function in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 289:2663–2672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espeland MA, Rapp SR, Shumaker SA, Brunner R, Manson JE, Sherwin BB, Hsia J, Margolis KL, Hogan PE, Wallace R, Dailey M, Freeman R, Hays J 2004 Conjugated equine estrogens and global cognitive function in postmenopausal women: Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study. JAMA 291:2959–2968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick SM, Coker LH, Maki PM, Rapp SR, Espeland MA, Shumaker SA 2004 The Women’s Health Initiative Study of Cognitive Aging (WHISCA): a randomized clinical trial of the effects of hormone therapy on age-associated cognitive decline. Clinical Trials 1:440–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogervorst E, Yaffe K, Richards M, Huppert F 2002 Hormone replacement therapy for cognitive function in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (Online):CD003122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki P, Hogervorst E 2003 The menopause and HRT. HRT and cognitive decline. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 17:105–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick SM, Maki PM, Rapp SR, Espeland MA, Brunner R, Coker LH, Granek IA, Hogan P, Ockene JK, Shumaker SA 2006 Effects of combination estrogen plus progestin hormone treatment on cognition and affect. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:1802–1810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick SM, Metter EJ, Zonderman AB 1997 Estrogen replacement therapy and longitudinal decline in visual memory: a possible protective effect? Neurology 49:1491–1497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki PM, Zonderman AB, Resnick SM 2001 Enhanced verbal memory in nondemented elderly women receiving hormone-replacement therapy. Am J Psychiatry 158:227–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wactawski-Wende J 1998 Design of the Women’s Health Initiative clinical trial and observational study. The Women’s Health Initiative Study Group. Control Clin Trials 19:61–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumaker SA, Reboussin BA, Espeland MA, Rapp SR, McBee WL, Dailey M, Bowen D, Terrell T, Jones BN 1998 The Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS): a trial of the effect of estrogen therapy in preventing and slowing the progression of dementia. Control Clin Trials 19:604–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, Jackson RD, Beresford SA, Howard BV, Johnson KC, Kotchen JM, Ockene J 2002 Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 288:321–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, Bassford T, Beresford SA, Black H, Bonds D, Brunner R, Brzyski R, Caan B, Chlebowski R, Curb D, Gass M, Hays J, Heiss G, Hendrix S, Howard BV, Hsia J, Hubbell A, Jackson R, Johnson KC, Judd H, Kotchen JM, Kuller L, LaCroix AZ, Lane D, Langer RD, Lasser N, Lewis CE, Manson J, Margolis K, Ockene J, O'Sullivan MJ, Phillips L, Prentice RL, Ritenbaugh C, Robbins J, Rossouw JE, Sarto G, Stefanick ML, Van Horn L, Wactawski-Wende J, Wallace R, Wassertheil-Smoller S 2004 Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 291:1701–1712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis DC, Massman PJ, Kaplan E, McKee R, Kramer JH, Gettman D 1991 Alternate form of the California Verbal Learning Test: development and reliability. Clin Neuropsychol 5:154–162 [Google Scholar]

- Shock NW, Greulich RC, Andres R, Arenberg D, Costa Jr PT, Lakatta E, Tobin JD 1984 Normal human aging: the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office [Google Scholar]

- Teng EL, Chui HC 1987 The Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) Exam. J Clin Psychiatry 48:314–318 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips SM, Sherwin BB 1992 Effects of estrogen on memory function in surgically menopausal women. Psychoneuroendocrinology 17:485–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder EF, Schechtman KB, Birge SJ, Williams DB, Kohrt WM 2001 Effects of hormone replacement therapy on cognitive performance in elderly women. Maturitas 38:137–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe K, Vittinghoff E, Ensrud KE, Johnson KC, Diem S, Hanes V, Grady D 2006 Effects of ultra-low-dose transdermal estradiol on cognition and health-related quality of life. Arch Neurol 63:945–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pefanco MA, Kenny AM, Kaplan RF, Kuchel G, Walsh S, Kleppinger A, Prestwood K 2007 The effect of 3-year treatment with 0.25 mg/day of micronized 17β-estradiol on cognitive function in older postmenopausal women. J Am Geriatr Soc 55:426–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida OP, Lautenschlager NT, Vasikaran S, Leedman P, Gelavis A, Flicker L 2006 A 20-week randomized controlled trial of estradiol replacement therapy for women aged 70 years and older: effect on mood, cognition and quality of life. Neurobiol Aging 27:141–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson E 1990 Estrogen-related variations in human spatial and articulatory motor skills. Psychoneuroendocrinology 15:97–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki PM, Rich JB, Rosenbaum RS 2002 Implicit memory varies across the menstrual cycle: estrogen effects in young women. Neuropsychologia 40:518–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer U, Hausmann M 2009 Estrogen therapy affects right hemisphere functioning in postmenopausal women. Horm Behav 55:228–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemppainen JA, Langley E, Wong CI, Bobseine K, Kelce WR, Wilson EM 1999 Distinguishing androgen receptor agonists and antagonists: distinct mechanisms of activation by medroxyprogesterone acetate and dihydrotestosterone. Mol Endocrinol 13:440–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll I, Resnick SM 2007 Testosterone and cognition in normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease: an update. Curr Alzheimer Res 4:33–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanick ML, Cochrane BB, Hsia J, Barad DH, Liu JH, Johnson SR 2003 The Women’s Health Initiative postmenopausal hormone trials: overview and baseline characteristics of participants. Ann Epidemiol 13:S78–S86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick SM, Espeland MA, Jaramillo SA, Hirsch C, Stefanick ML, Murray AM, Ockene J, Davatzikos C 2009 Postmenopausal hormone therapy and regional brain volumes: the WHIMS-MRI Study. Neurology 72:135–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]