Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the association of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with nevirapine concentrations following intra-partum single-dose nevirapine.

Methods

Plasma and DNA samples were obtained from 330 HIV-infected Thai women who received intra-partum single-dose nevirapine in the PHPT-2 clinical trial to prevent perinatal HIV transmission. Nine SNPs within CYP2B6, CYP3A4 and ABCB1 were genotyped by real-time PCR. Nevirapine plasma concentrations were determined by HPLC and used in a population pharmacokinetic analysis.

Results

Higher nevirapine exposure was observed in women carrying the CYP2B6 516G>T polymorphism, but this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.054). The TGATC CYP2B6 haplotype (g.3003T, 516G, 785A, g.18492T and g.21563C) was associated with increased nevirapine clearance and lower exposure (P = 0.0029). The median time for nevirapine concentrations to reach 10 ng/mL post-partum (nevirapine IC50 for HIV-1) was 14 days [interquartile range (IQR, 14–18)] for TGATC homozygotes, 16 days (14–20) for TGATC heterozygotes and 18 days (14–20) for non-TGATC homozygotes (P = 0.020).

Conclusions

The CYP2B6 516G>T impact on nevirapine concentrations was less pronounced after intra-partum single-dose nevirapine than reported under steady-state conditions, perhaps due to lack of enzyme auto-induction at the time of dosing. Although the TGATC CYP2B6 haplotype may shorten the persistence of nevirapine post-partum, its practical implications for the prevention of HIV transmission or selection of resistance mutations are likely limited.

Keywords: pharmacogenetics, single nucleotide polymorphisms, SNPs

Introduction

Intra-partum single-dose nevirapine in addition to standard zidovudine prophylaxis initiated at 28 weeks gestation is recommended for non-immunocompromised women for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 (PMTCT) in resource-limited settings.1 This PMTCT regimen can reduce HIV mother-to-child transmission to ∼2%.2 However, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) resistance mutations have been detected in 20%–70% of women post-partum who received intra-partum single-dose nevirapine and these mutations can impact the success of subsequent NNRTI-based therapies, particularly when initiated within 6 months of exposure.3,4

Nevirapine concentrations can persist in the plasma for up to 4 weeks post-partum following intra-partum single-dose nevirapine.5 This prolonged period of monotherapy post-partum, in the presence of replicating viruses, can increase the risk of selecting for NNRTI resistance mutations. Indeed, high plasma nevirapine concentrations at 48 h post-partum have been associated with the emergence of NNRTI-resistant virus post-partum in mothers following intra-partum single-dose nevirapine.6 However, the duration of nevirapine persistance is highly variable with nevirapine concentrations remaining >10 ng/mL (nevirapine IC50 for wild-type HIV-1) for 1–4 weeks post-partum.

Genetic polymorphisms in drug metabolizing enzymes and transporters have been shown to contribute towards antiretroviral inter-individual drug variability.7 Nevirapine is extensively metabolized via cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes, in particular the isoenzymes CYP2B6 and CYP3A.8 A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in CYP2B6 516G>T, which is associated with a significant reduction in enzyme catalytic activity in the liver,9–11 has been reported to influence nevirapine pharmacokinetics during chronic treatment. Higher nevirapine exposure [area under the concentration–time curve (AUC)] in a Swiss cohort12 and trough (pre-dose) concentrations in Ugandan patients13 have been associated with the homozygous CYP2B6 516TT genotype. In children, in addition to slower nevirapine oral clearance, the CYP2B6 516TT variant was associated with an improved immunological response.14

Host genetic polymorphisms associated with a slower nevirapine oral clearance following a single dose could be problematic as the longer nevirapine concentrations persist post-partum the higher the risk of selecting new NNRTI resistance mutations.

To date, no data are available on the influence of host genetic polymorphisms of drug metabolizing enzymes and transporters on nevirapine concentrations following intra-partum single-dose nevirapine in HIV-infected women. The purpose of this study was to determine whether polymorphisms in CYP2B6, CYP3A4 and ABCB1 impact nevirapine plasma concentrations post-partum in Thai HIV-infected women who received intra-partum single-dose nevirapine for the prevention of perinatal HIV transmission.

Materials and methods

Study population

All plasma and DNA samples were obtained from women who participated in the perinatal HIV prevention trial-2 (PHPT-2) clinical trial (NCT00398684; www.clinicaltrials.gov), a multicentre, randomized, three-arm, double-blind, controlled study performed between 2001 and 2003 assessing the efficacy in preventing mother to child HIV transmission of intra-partum single-dose nevirapine given at the onset of labour and to the infant 48–72 h after birth in addition to zidovudine starting at 28 weeks or as soon as possible thereafter.2

In a previous pharmacokinetic sub-study of the PHPT-2 trial we assessed the nevirapine plasma concentrations post-partum in 110 women who received an intra-partum nevirapine dose.5 All 110 women were also included in this analysis. For this pharmacogenetic study, additional women from PHPT-2 were selected based on the timing of their post-partum sample and time of nevirapine intake. To maximize the number of women with detectable nevirapine concentrations post-partum, women with plasma samples available at delivery and 9–11 days post-partum were selected. Women who received more than one dose of nevirapine (i.e. for false labour or a prolonged labour) were excluded. No concomitant treatments with drugs that affect nevirapine pharmacokinetics were used in these women. A total of 330 women had DNA and plasma samples available for analysis. Among these women, 640 plasma samples between delivery and 21 days post-partum were available.

All women provided written informed consent for the PHPT-2 study (performed between 2001 and 2003), which included the use of stored samples for future research following specific ethical clearance. This specific retrospective analysis, performed on anonymized DNA and plasma samples, was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital and the Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Chiang Mai University, which agreed a request for a waiver of consent.

Identification of genetic variants

In PHPT-2, venous blood samples were obtained from mothers immediately after delivery and 10 days, 6 weeks and 4 months post-partum for pharmacokinetic and virological studies. For each blood draw the remaining EDTA cell pellets were stored at −20°C. DNA was isolated from the stored EDTA cell pellets using the QIAamp® DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Genomic DNA was quantified by a UV spectrophotometer ND-1000 (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA), at 260 nm. Genetic polymorphisms were identified by real-time PCR as previously described.15 A total of nine SNPs within CYP2B6, CYP3A4 and ABCB1 were genotyped. The GenBank accession numbers of CYP2B6, CYP3A4 and ABCB1 used in this study are NG_000008.7, NG_000004.3 and NT_007933.15, respectively. Within CYP2B6, five SNPs were selected: two SNPs, c.516G>T (rs3745274) and c.785A>G (rs2279343) previously reported to influence enzyme activity;10 and three CYP2B6 tagSNPs, g.3003T>C (rs8100458), g.18492T>C (rs2279345) and g.21563C>T (rs8192719), identified using HapMap (www.hapmap.org) data on Japanese and Han Chinese populations with an r2 of >0.8. Three CYP3A4 SNPs were selected: g.–486G>A; g.–392A>G (rs2740574); and c.878T>C (rs28371759). These were identified using the CYP3A4 SNP database available through the Thailand SNP Discovery Project (www4a.biotec.or.th/thaisnp) and were within coding or promoter regions. One SNP in the ABCB1 gene, c.3435C>T (rs1045642), that has been reported to be associated with antiretroviral drug concentrations was also selected.16 Pre-designed TaqMan assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) were used to genotype CYP2B6 g.3003T>C (assay ID C_2818167_10), c.516G>T (assay ID C_7817765_60), g.18492T>C (assay ID C_26823975_10) and g.21563C>T (assay ID C_22275631_10) and ABCB1 c.3435C>T (assay ID C_7586657_20). CYP2B6 c.785A>G, CYP3A4 g.–486G>A and CYP3A4 g.–392A>G genotyping was performed using customized TaqMan assays (Applied Biosystems). The sequences of primers and probes were: CYP2B6 c.785A>G, TGGAGAAGCACCGTGAAACC (forward), TGGAGCAGGTAGGTGTCGAT (reverse), VIC-CCCCCAAGGACCTC-MGB (wild-type), FAM-CCCCAGGGACCTC-MGB (mutant); CYP3A4 g.–486G>A, GTTTGGAAGGATGTGTAGGAGTCTT (forward), AGCCACACCTACAGATCTTTACCTA (reverse), VIC-ACAGGCACACTCC-MGB (wild-type), FAM-CACAGACACACTCC-MGB (mutant); and g.–392A>G, TGGAATGAGGACAGCCATAGAGA (forward), AGTGGAGCCATTGGCATAAAATCT (reverse), VIC-AAGGGCAAGAGAGAG-MGB (wild-type), FAM-AAGGGCAGGAGAGAG-MGB (mutant). Genotyping of CYP3A4 c.878T>C was performed by SimpleProbe. The primers forward (5′-CCAGTGTACCTCTGAATTGC-3′) and reverse (5′-TAAAGATAATTGATTGGGCCACGA-3′) and SimpleProbe (5′-CAGCTCTITCCGATCCGGAG-3′) were used in the PCR.

Sample preparation and nevirapine assay

Blood samples were centrifuged, and the plasma was aliquotted and frozen at –20°C. Plasma nevirapine concentrations were measured at the Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Chiang Mai University, using an HPLC assay described previously.17 The nevirapine assay had an average accuracy of 104%–112%, precision (inter- and intra-assay) of <5% for the coefficient of variation and a lower limit of quantification of 50 ng/mL. This laboratory participates in the international external quality control programme of the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG), Pharmacology Quality Control (Precision Testing) programme.18

Population pharmacokinetic analysis

Population pharmacokinetic analysis was performed using the population mixed-effect modelling program NONMEM VI.19 Nevirapine concentration data from the additional 220 women available in this study were nested with the nevirapine concentration data from our prior population pharmacokinetic analysis using a one-compartment model with first order absorption.5 A total of 640 plasma samples were available. Post-hoc individual parameters were used to estimate the AUC and duration of time nevirapine concentration exceeded 10 ng/mL post-partum.

Statistical analyses

Deviation of genotype frequencies from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium expectations was assessed using exact tests.20 A Kruskal–Wallis test was used to assess where there were significant differences in nevirapine AUC and the median time for nevirapine concentrations to reach 10 ng/mL post-partum among the three genotypes. Mann–Whitney U-tests were used to compare nevirapine AUC between two genotypes. The QTLHAPLO program21 was used to identify the association between the CYP2B6 haplotypes and the nevirapine AUC, using inferred haplotypes from individual genotypes at loci by an expectation-maximization algorithm, as well as their quantitative phenotypes, to estimate the parameters of the distribution of the phenotypes for subjects with and without a particular haplotype by a likelihood ratio test. The most significant haplotype from QTLHAPLO that survived multiple test correction was used to assess association with nevirapine AUC. Univariate statistical analysis was conducted using a linear regression model for baseline characteristics [age, weight, creatinine, serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase (SGPT), HIV-RNA viral load, CD4 cell count] and Kruskal–Wallis test for genetic variables. To determine the independent role of the genetic polymorphisms, a multivariate analysis was conducted using a backward stepwise linear regression model adjusting for baseline characteristics (dependent variable: nevirapine AUC and independent variables: baseline characteristics and all genetic variables). The multivariate analysis was repeated restricting to the variables associated with the nevirapine AUC in the univariate analysis at P < 0.25. All statistics tests were performed two-sided by using the R statistic program (version 2.5.1)22 and statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics and frequencies of genetic polymorphisms

Three-hundred and thirty HIV-infected Thai pregnant women who participated in the PHPT-2 clinical trial were included in this retrospective analysis. Median [interquartile range (IQR)] age was 27 years (23–30), weight (taken at the last study visit before delivery) 63 kg (56–68), creatinine 0.60 mg/dL (0.50–0.70), SGPT 14 U/L (10–24), CD4 cell count 375 cells/mm3 (235–532) and HIV-1-RNA viral load 3.91 log10 copies/mL (3.21–4.53).

All 330 individuals were genotyped for nine SNPs: CYP2B6 (five SNPs); CYP3A4 (three SNPs); and ABCB1 (one SNP). The frequencies of each polymorphism are summarized in Table 1. All polymorphisms were found to be in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. The minor allele frequencies (MAFs) for the CYP2B6 polymorphisms ranged between 0.25 and 0.37, while the MAFs for the CYP3A4 polymorphisms assessed were all <0.02. The MAF for the ABCB1 3435C>T polymorphism was 0.44.

Table 1.

Genetic polymorphisms/haplotypes and nevirapine exposure (AUC)

| Genetic polymorphism | n (%) (n = 330) | MAF | Nevirapine AUC (μg·h/mL), median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2B6 g.3003T>C (rs8100458) | |||

| TT | 142 (43.0) | C = 0.353 | 154.2 (132.0–181.3) |

| CT | 143 (43.3) | 153.2 (131.7–181.5) | |

| CC | 45 (13.6) | 164.4 (139.3–187.0) | |

| P value | 0.58 | ||

| CYP2B6 c.516G>T; g.15631G>T (rs3745274) | |||

| GG | 142 (43.0) | T = 0.336 | 148.3 (130.0–177.9) |

| GT | 154 (46.7) | 159.4 (135.0–190.6) | |

| TT | 34 (10.3) | 166.6 (150.4–180.0) | |

| P value | 0.054 | ||

| CYP2B6 c.785A>G; g.18053A>G (rs2279343) | |||

| AA | 126 (38.2) | G = 0.374 | 152.4 (130.9–179.8) |

| AG | 161 (48.8) | 157.0 (132.8–187.3) | |

| GG | 43 (13.0) | 164.2 (143.0–181.4) | |

| P value | 0.20 | ||

| CYP2B6 g.18492T>C (rs2279345) | |||

| TT | 187 (56.7) | C = 0.252 | 163.7 (138.2–182.4) |

| CT | 120 (36.4) | 145.5 (129.4–179.4) | |

| CC | 23 (7.0) | 142.5 (130.6–171.4) | |

| P value | 0.041* | ||

| CYP2B6 g.21563C>T (rs8192719) | |||

| CC | 143 (43.3) | T = 0.339 | 149.0 (129.6–176.8) |

| CT | 150 (45.5) | 159.5 (134.2–186.4) | |

| TT | 37 (11.2) | 170.0 (147.9–192.0) | |

| P value | 0.019* | ||

| CYP3A4 g.−486G>A | |||

| GG | 329 (99.7) | A = 0.002 | 155.0 (132.1–181.8) |

| AG | 1 (0.3) | 139.4 | |

| AA | 0 (0.0) | ||

| P value | — | ||

| CYP3A4 g.−392A>G (rs2740574) | |||

| AA | 328 (99.4) | G = 0.003 | 155.3 (132.3–181.8) |

| AG | 2 (0.6) | 120.8 (113.0–128.5) | |

| GG | 0 (0.0) | ||

| P value | — | ||

| CYP3A4 c.878T>C; g.20079T>C (rs28371759) | |||

| TT | 320 (97.0) | C = 0.015 | 155.3 (132.1–181.8) |

| CT | 10 (3.0) | 145.7 (124.6–188.0) | |

| CC | 0 (0.0) | ||

| P value | 0.87 | ||

| ABCB1 c.3435C>T; g.90856C>T (rs1045642) | |||

| CC | 107 (32.4) | T = 0.435 | 148.0 (132.2–188.6) |

| CT | 159 (48.2) | 157.0 (131.9–180.4) | |

| TT | 64 (19.4) | 159.8 (135.7–182.2) | |

| P value | 0.79 | ||

| CYP2B6 haplotype | |||

| non-TGATC | 197 (59.7) | 164.0 (141.3–186.5) | |

| TGATC heterozygous | 114 (34.5) | 143.1 (128.1–177.6) | |

| TGATC homozygous | 19 (5.8) | 139.0 (129.6–159.0) | |

| P value | 0.0029* |

*P < 0.05 using a Kruskal–Wallis test.

CYP2B6, CYP3A4 and ABCB1 genetic polymorphisms and nevirapine drug exposure post-partum

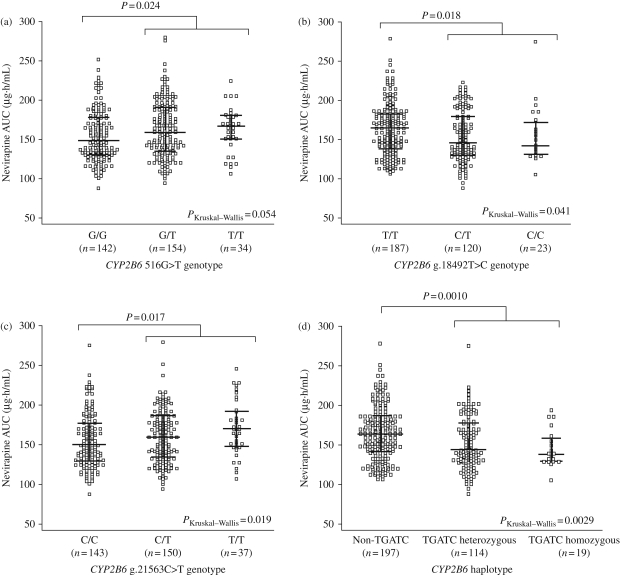

The median nevirapine AUCs for the CYP2B6, CYP3A4 and ABCB1 polymorphisms are summarized in Table 1. The CYP2B6 516G>T polymorphism was not significantly associated with nevirapine AUC, but there was a trend towards higher exposure with the T/T genotype (P = 0.054). The median nevirapine AUC for women with either the 516 T/T or G/T genotype was significantly higher than those with the G/G genotype (P = 0.024, Figure 1a). Among the other genetic polymorphisms evaluated within CYP2B6, two tagSNPs in CYP2B6 were significantly associated with nevirapine AUC. CYP2B6 g.18492T>C polymorphism was associated with a lower nevirapine drug exposure (P = 0.041). Median nevirapine AUC for women with the g.18492 C/T or C/C genotype was significantly lower than those with the T/T genotype (P = 0.018, Figure 1b). The CYP2B6 g.21563C>T polymorphism was associated with a higher nevirapine drug exposure (P = 0.019). Nevirapine exposure for women with the g.21563 C/T or T/T genotype was significantly higher than those women with the g.21563C/C genotype (P = 0.017, Figure 1c). Among the other genetic polymorphisms evaluated within CYP3A4 and ABCB1, none was significantly associated with nevirapine exposure.

Figure 1.

Nevirapine plasma exposure (AUC) and CYP2B6 polymorphisms (a) 516G>T, (b) g.18492T>C and (c) g.21563C>T, and (d) CYP2B6 TGATC haplotype. Each circle represents one subject, the middle bar indicates the median, and the upper and lower bars represent the IQR. Numbers of subjects are indicated below each group. A Kruskal–Wallis test was used to assess where there were significant differences in nevirapine AUC among the three genotypes. Mann–Whitney U-tests were used to compare nevirapine AUC between two genotypes.

Influence of a CYP2B6 haplotype (TGATC) on nevirapine drug exposure following intra-partum single-dose nevirapine

The frequencies of women with the CYP2B6 TGATC haplotype (g.3003T, 516G, 785A, g.18492T and g.21563C) were 59.7% (n = 197), 34.5% (n = 114) and 5.8% (n = 19) for non-TGATC, TGATC heterozygous and TGATC homozygous genotypes, respectively. This haplotype was found to be significantly associated with lower nevirapine AUC (P = 0.0029). Median (IQR) nevirapine AUCs were 164.0 (141.3–186.5), 143.1 (128.1–177.6) and 139.0 (129.6–159.0) µg·h/mL for women with non-TGATC, TGATC heterozygous and TGATC homozygous genotypes, respectively. Median nevirapine AUC for women with the non-TGATC haplotype was significantly higher than those with TGATC heterozygous or TGATC homozygous genotypes (P = 0.0010, Figure 1d).

Multivariate analysis

To determine the independent role of the genetic polymorphisms, a multivariate analysis was conducted adjusting for the baseline characteristics and genetic variables; weight, creatinine, CYP2B6 g.18492T>C polymorphism and the TGATC haplotype remained significantly associated with nevirapine AUC in a multivariate analysis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis with nevirapine AUC as the dependent variable

| Univariate |

Multivariate |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | P value | coefficient | P value |

| Age | 0.870 | — | — |

| Weight | 0.015 | −0.407 | 0.031 |

| Creatinine | 0.063 | 19.00 | 0.027 |

| SGPT | 0.220 | — | — |

| HIV-RNA viral load | 0.461 | — | — |

| CD4 cell count | 0.598 | — | — |

| CYP2B6 | |||

| g.3003T>C (rs8100458) | 0.576 | — | — |

| c.516G>T (rs3745274) | 0.054 | — | — |

| c.785A>G (rs2279343) | 0.201 | — | — |

| g.18492T>C (rs2279345) | 0.041 | 24.47 | 0.009 |

| g.21563C>T (rs8192719) | 0.019 | — | — |

| TGATC haplotype | 0.003 | −33.73 | 0.001 |

| CYP3A4 | |||

| g.–486G>A | — | — | — |

| g.–392A>G (rs2740574) | — | — | — |

| c.878T>C (rs28371759) | 0.869 | — | — |

| ABCB1 | |||

| c.3435C>T (rs1045642) | 0.788 | — | — |

Impact of CYP2B6 polymorphisms and haplotype (TGATC) on the persistence of nevirapine concentrations post-partum

The relationship between CYP2B6 polymorphisms and the time for nevirapine plasma concentrations to decrease to 10 ng/mL post-partum (approximate nevirapine IC50 for wild-type HIV-1) was assessed. The CYP2B6 haplotype, TGATC, was significantly associated with the median time for nevirapine concentrations to reach 10 ng/mL (P = 0.020). In the women with non-TGATC, TGATC heterozygous and TGATC homozygous genotypes, median times for nevirapine concentrations to reach 10 ng/mL were 18 days (IQR, 14–20), 16 days (IQR, 14–20) and 14 days (IQR, 14–18), respectively. Median time for nevirapine concentrations to reach 10 ng/mL in the women with non-TGATC was statistically significantly longer than those with a TGATC heterozygous or TGATC homozygous genotype (P = 0.0060). For the individual CYP2B6 polymorphisms, 516G>T, g.18492T>C and g.21563C>T, none was significantly associated with the time nevirapine concentrations took to reach 10 ng/mL post-partum (P = 0.050, 0.12 and 0.16, respectively).

Discussion

In this study of HIV-infected Thai women who received a single intra-partum dose of nevirapine for the prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV-1, we found that host genetic polymorphisms of drug metabolizing enzymes can impact nevirapine concentrations post-partum. Interestingly, the increase in nevirapine exposure following intra-partum single-dose nevirapine was found to be less pronounced with the CYP2B6 516G>T polymorphism compared with that reported under steady-state conditions and the association with nevirapine exposure was borderline (P = 0.054). Other CYP2B6 genetic polymorphisms, namely g.18492T>C, g.21563C>T and the haplotype TGATC, were found to significantly influence intra-partum single-dose nevirapine exposure. The CYP2B6 TGATC haplotype was associated with a shorter time for nevirapine concentrations to reach 10 ng/mL post-partum.

Within our study population of Thai women, the MAF for CYP2B6 516G>T was 0.336, which is similar to that reported in Black patients (0.34), but higher than reported for Caucasians (0.29).23 Compared with other Asian populations, the MAF for CYP2B6 516G>T is higher in the reported study [Taiwan (0.141), Korean (0.15), Japanese (0.16) and Han Chinese (0.21)], with the exception of the Southern Chinese population (0.345).24 Several studies have shown that the CYP2B6 516G>T polymorphism was associated with higher nevirapine plasma concentrations following chronic treatment in adults,12,13 whether administered once daily or twice daily.25 Given this data it may be expected that the CYP2B6 516G>T polymorphism would also influence nevirapine concentrations following a single nevirapine intra-partum dose, but the impact was less pronounced.

Several possible reasons could account for the different impact the CYP2B6 516G>T polymorphism has on nevirapine following chronic or single-dose administration. First, the physiological changes that manifest during pregnancy that affect drug disposition, particularly the temporal changes of hepatic metabolizing enzymes activities,26 may reduce the impact of the CYP2B6 516G>T polymorphism. Secondly, the pharmacokinetics of intra-partum single-dose nevirapine and multidose nevirapine are quite different. During the first 2 weeks of multidose nevirapine treatment there is a 1.5- to 2-fold increase in nevirapine oral clearance and a decrease in the plasma terminal half-life from 45 to 25 h.27 These changes in nevirapine pharmacokinetics have been attributed to the autoinduction of CYP3A4 and 2B6 enzymes,28 and the differences in enzymes activities between single-dose and steady-state conditions may explain the limited impact of the CYP2B6 516G>T polymorphism on nevirapine concentrations following a single dose. Recently, in a small study of 34 healthy non-pregnant adults who were administered intra-partum single-dose nevirapine the CYP2B6 516G>T polymorphism was not associated with nevirapine exposure.29 These data suggest that it is the lack of autoinduction of the CYP3A4 and 2B6 enzymes and not the physiological changes during pregnancy that is the major factor reducing the impact of the CYP2B6 516G>T polymorphism on nevirapine concentrations following a single intra-partum dose. Overall, in the context of intra-partum single-dose nevirapine for the prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV the CYP2B6 516G>T polymorphism seems to have limited impact on nevirapine pharmacokinetics.

We identified two tagSNPs in CYP2B6 that were significantly associated with nevirapine drug concentrations and their MAFs were relatively similar to that of CYP2B6 516G>T. The CYP2B6 g.21563C>T polymorphism was associated with higher nevirapine drug exposure while the CYP2B6 g.18492T>C polymorphism was associated with lower nevirapine drug exposure. The opposing impact of these two tagSNPs on nevirapine exposure demonstrates the complexity of nevirapine metabolism and genetic polymorphism. Indeed, a CYP2B6 haplotype, TGATC (g.3003T, 516G, 785A, g.18492T and g.21563C), a combination of alleles within CYP2B6, was found to influence nevirapine metabolism in this population. Women with the non-TGATC homozygous genotype were slower metabolizers compared with women with the TGATC homozygous genotype and nevirapine concentrations above its IC50 (∼10 ng/mL) persisted longer post-partum. Although higher nevirapine concentrations in the early post-partum period have been associated with the emergence of NNRTI-resistant virus post-partum,6 the exact nevirapine concentration that continues to increase this risk of selecting drug resistant viruses has not been defined. There is a possibility that women with the non-TGATC homozygous genotype could have nevirapine concentrations persisting for a few days longer than women with this haplotype, but the consequence of these few additional days on the overall risk of selecting NNRTI resistance is unknown. Given the proxy status of these tagSNPs, it is possible that other genetic markers (SNPs or insertions/deletions) within linkage disequilibrium are the actual functional polymorphisms.

The lack of an association between CYP2B6 516G>T polymorphisms and nevirapine exposure may also have been related to the role that CYP3A4 contributes to nevirapine metabolism following a single dose. Unfortunately, the MAFs of the three CYP3A4 polymorphisms assessed in this study were all <0.02, therefore the association with nevirapine exposure could not be fully assessed. During chronic nevirapine treatment, CYP3A4, as well as CYP3A5, polymorphisms were not associated with nevirapine trough concentrations,13 but the other CYP3A4 polymorphisms following both chronic and single dose administrations should continue to be assessed.

The ABCB1 gene encodes P-glycoprotein, which is a drug efflux transporter in the intestine, liver, kidney and blood–brain barrier.25 The ABCB1 3435C>T polymorphism has been associated with antiretroviral drug concentrations,16 but conflicting results have been reported on its effect on treatment response.30,31 Despite in vitro data suggesting that nevirapine is not a substrate for P-glycoprotein,32 the effect of ABCB1 3435C>T polymorphism on nevirapine concentrations has been investigated and shown to be associated with nevirapine trough concentrations,33 although this was not confirmed in a subsequent study.13 The latter study is consistent with our finding that we found no association between the ABCB1 3435C>T polymorphism and nevirapine concentrations post-partum. However, it is becoming increasing clear that variability in ABCB1 and CYP3A4 stems predominantly from genetic variability in the transcription factors that regulate their expression. For example, the pregnane-X-receptor (PXR) regulates CYP3A4 and associations between PXR polymorphisms and CYP3A4 activity in vitro34 and in vivo35 have been reported. Thus the influence of transcription factor polymorphisms and nevirapine exposure following a single intra-partum dose warrants further investigation.

Intra-partum single-dose nevirapine, in addition to zidovudine prophylaxis from 28 weeks gestation, remains an important and effective regimen for the prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV in resource-limited settings, but minimizing the risk of selecting NNRTI resistance for mothers, and infected children, must be addressed given that generic fixed-dose combination regimens containing nevirapine are the most commonly used first-line treatments in such settings. The World Health Organization (WHO) currently recommends 7 days post-partum antiretroviral treatment with zidovudine plus lamivudine to reduce the development of NNRTI resistance,26 but this may not be sufficient to cover all women. Studies are ongoing to address this question, such as the IMPAACT P1032 trial (NCT00109590; www.clinicaltrials.gov) in Thailand, which is comparing 1 week versus 1 month of antiretroviral post-partum treatment at preventing the development of nevirapine resistance mutations. Due to the relatively small impact of CYP2B6 polymorphisms on the persistence of nevirapine concentrations post-partum, it is unlikely that a woman's CYP2B6 genotype will need to be taken into account when determining the optimal post-partum antiretroviral strategy to prevent NNRTI mutations.

In conclusion, the data obtained in the present study suggest that following a single intra-partum dose of nevirapine, CYP2B6 polymorphisms account for some of the inter-patient variability of nevirapine concentrations and could cause nevirapine concentrations to persist slightly longer in some women. Theoretically, women who have nevirapine concentrations persisting longer would have a higher risk of selecting new NNRTI resistance mutations, but, given the magnitude of the effect of CYP2B6 polymorphisms on the persistence of nevirapine concentrations post-partum, the practical implications of these findings for the prevention of HIV transmission or selection of resistance mutations are likely limited.

Funding

This work was supported by grant funding from NIH R01 39615, ANRS 12-08, Institut de Recherche pour le Développement and Thailand Center of Excellence for Life Sciences (TCELS).

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our co-investigators Dr Aram Limtrakul (Health Promotion Center Region 10, Chiang Mai), Dr Wanmanee Matanasaravoot (Lamphun Hospital), Dr Suraphan Sangsawang (Phayao Provincial Hospital), Dr Jullapong Achalapong (Chiangrai Prachanukroh Hospital), Dr Chaiwat Putiyanun (Chiang Kham Hospital), Dr Sivaporn Jungpichanvanich (Phan Hospital), Dr Sura Kunkongkapan (Mae Sai Hospital), Dr Sudanee Buranabanjasatean (Mae Chan Hospital), Dr Praparb Yuthavisuthi (Prapokklao Hospital), Dr Jirapan Ithisuknanth (Banglamung Hospital), Dr Nanthasak Chotivanich (Chonburi Hospital), Dr Surabhon Ariyadej (Rayong Hospital), Dr Somnoek Techapalokul (Klaeng Hospital), Dr Annop Kanjanasing (Chacheongsao Hospital), Dr Vorapin Gomuthbutra (Nakornping Hospital), Dr Pramote Kanchanakitsakul (Somdej Prapinklao Hospital), Dr Santhan Surawongsin (Nopparat Rajathanee Hospital), Dr Sinart Prommas (Bhumibol Adulyadej Hospital), Dr Woraprapa Laphikanont (Health Promotion Hospital Regional Center I), Dr Wittaya Pornkitprasarn (Somdej Pranangchao Sirikit Hospital), Dr Surachai Pipatnakulchai (Pranangklao Hospital), Dr Wiroj Wannapira (Buddhachinaraj Hospital), Dr Surachai Lamlertkittikul (Hat Yai Hospital), Dr Chuanchom Sakondhavat (Srinagarind Hospital), Dr Janyaporn Ratanakosol (Khon Kaen Hospital), Dr Narong Winiyakul (Health Promotion Centre, Region 6, Khon Kaen), Dr Nusra P. Ruttana-Aroongorn (Nong Khai Hospital), Dr Thammanoon Sukhumanant (Samutsakorn Hospital), Dr Yupa Srivarasat (Phaholpolphayuhasena Hospital), Dr Bunpode Suwannachat (Kalasin Hospital), Dr Veeradej Chalermpolprapa (Nakhonpathom Hospital), Dr Prapan Sabsanong (Samutprakarn Hospital), Dr Darapong langkafa (Prajaksilapakom Army Hospital), Dr Ruangyot Thongdej (Kranuan Crown Prince Hospital), Dr Sakchai Tonmat (Mahasarakam Hospital), Dr Wanchai Atthakorn (Roi-et Hospital) and Dr Nittaya Pinyotrakool (Ratchaburi Hospital). We would also like to thank Boehringer Ingelheim for providing nevirapine for PHPT-2, GlaxoSmithKline for providing zidovudine, the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH for providing nevirapine and Abbott Laboratories for providing the experimental material A86093, which was used as an internal standard in the HPLC nevirapine assay.

References

- 1.WHO Guidelines. Antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants: towards universal access. Recommendations for a public health approach. 2006 Version. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/pmtct/en/index.html. (29 June 2009, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lallemant M, Jourdain G, Le Coeur S, et al. Single-dose perinatal nevirapine plus standard zidovudine to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 in Thailand. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:217–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jourdain G, Ngo-Giang-Huong N, Le Coeur S, et al. Intrapartum exposure to nevirapine and subsequent maternal responses to nevirapine-based antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:229–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lockman S, Shapiro RL, Smeaton LM, et al. Response to antiretroviral therapy after a single, peripartum dose of nevirapine. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:135–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cressey TR, Jourdain G, Lallemant MJ, et al. Persistence of nevirapine exposure during the postpartum period after intrapartum single-dose nevirapine in addition to zidovudine prophylaxis for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38:283–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaix ML, Ekouevi DK, Peytavin G, et al. Impact of nevirapine (NVP) plasma concentration on selection of resistant virus in mothers who received single-dose NVP to prevent perinatal human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmission and persistence of resistant virus in their infected children. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:896–901. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00910-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cressey TR, Lallemant M. Pharmacogenetics of antiretroviral drugs for the treatment of HIV-infected patients: an update. Infect Genet Evol. 2007;7:333–42. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erickson DA, Mather G, Trager WF, et al. Characterization of the in vitro biotransformation of the HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitor nevirapine by human hepatic cytochromes P-450. Drug Metab Dispos. 1999;27:1488–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jinno H, Tanaka-Kagawa T, Ohno A, et al. Functional characterization of cytochrome P450 2B6 allelic variants. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003;31:398–403. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.4.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lang T, Klein K, Fischer J, et al. Extensive genetic polymorphism in the human CYP2B6 gene with impact on expression and function in human liver. Pharmacogenetics. 2001;11:399–415. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200107000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xie HJ, Yasar U, Lundgren S, et al. Role of polymorphic human CYP2B6 in cyclophosphamide bioactivation. Pharmacogenomics J. 2003;3:53–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rotger M, Colombo S, Furrer H, et al. Influence of CYP2B6 polymorphism on plasma and intracellular concentrations and toxicity of efavirenz and nevirapine in HIV-infected patients. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005;15:1–5. doi: 10.1097/01213011-200501000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Penzak SR, Kabuye G, Mugyenyi P, et al. Cytochrome P450 2B6 (CYP2B6) G516T influences nevirapine plasma concentrations in HIV-infected patients in Uganda. HIV Med. 2007;8:86–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2007.00432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saitoh A, Sarles E, Capparelli E, et al. CYP2B6 genetic variants are associated with nevirapine pharmacokinetics and clinical response in HIV-1-infected children. AIDS. 2007;21:2191–9. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282ef9695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chantarangsu S, Cressey T, Mahasirimongkol S, et al. Comparison of the TaqMan and LightCycler systems in evaluation of CYP2B6 516G>T polymorphism. Mol Cell Probes. 2007;21:408–11. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fellay J, Marzolini C, Meaden ER, et al. Response to antiretroviral treatment in HIV-1-infected individuals with allelic variants of the multidrug resistance transporter 1: a pharmacogenetics study. Lancet. 2002;359:30–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07276-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Droste JA, Verweij-Van Wissen CP, Burger DM. Simultaneous determination of the HIV drugs indinavir, amprenavir, saquinavir, ritonavir, lopinavir, nelfinavir, the nelfinavir hydroxymetabolite M8, and nevirapine in human plasma by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. Ther Drug Monit. 2003;25:393–9. doi: 10.1097/00007691-200306000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holland DT, DiFrancesco R, Stone J, et al. Quality assurance program for clinical measurement of antiretrovirals: AIDS clinical trials group proficiency testing program for pediatric and adult pharmacology laboratories. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:824–31. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.3.824-831.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beal SL, Sheiner LB, Boeckmann AJ. University of California; 1994. NONMEM Users Guide. San Francisco: NONMEM Project Group. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wigginton JE, Cutler DJ, Abecasis GR. A note on exact tests of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:887–93. doi: 10.1086/429864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shibata K, Ito T, Kitamura Y, et al. Simultaneous estimation of haplotype frequencies and quantitative trait parameters: applications to the test of association between phenotype and diplotype configuration. Genetics. 2004;168:525–39. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.029751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Development Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 2007 www.R-project.org. (29 June 2009, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wyen C, Hendra H, Vogel M, et al. Impact of CYP2B6 983T>C polymorphism on non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor plasma concentrations in HIV-infected patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61:914–8. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu BY, Guo LP, Lee SS, et al. Genetic variability of CYP2B6 polymorphisms in four southern Chinese populations. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2100–3. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i14.2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahungu T, Smith C, Turner F, et al. Cytochrome P450 2B6 516G→T is associated with plasma concentrations of nevirapine at both 200 mg twice daily and 400 mg once daily in an ethnically diverse population. HIV Med. 2009;10:310–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mirochnick M, Capparelli E. Pharmacokinetics of antiretrovirals in pregnant women. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43:1071–87. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200443150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boehringer-Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Ltd. Viramune® (nevirapine) tablets and oral suspension. 2008 Prescribing information http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/ label/2008/020636s027,020933s017lbl.pdf. (29 June 2009, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lamson M, MacGregor T, Riska P, et al. Nevirapine induces both CYP3A4 and CYP2B6 metabolic pathways. Clin Pharmacol Ther; Abstracts of the One hundredth Annual Meeting of the American Society for Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics; 1999; San Antonio, TX. 1999. p. 137. Abstract PI-79. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haas DW, Gebretsadik T, Mayo G, et al. Associations between CYP2B6 polymorphisms and pharmacokinetics after a single dose of nevirapine or efavirenz in African Americans. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:872–80. doi: 10.1086/597125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brumme ZL, Dong WW, Chan KJ, et al. Influence of polymorphisms within the CX3CR1 and MDR-1 genes on initial antiretroviral therapy response. AIDS. 2003;17:201–8. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200301240-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haas DW, Smeaton LM, Shafer RW, et al. Pharmacogenetics of long-term responses to antiretroviral regimens containing efavirenz and/or nelfinavir: an Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1931–42. doi: 10.1086/497610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stormer E, von Moltke LL, Perloff MD, et al. Differential modulation of P-glycoprotein expression and activity by non-nucleoside HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitors in cell culture. Pharm Res. 2002;19:1038–45. doi: 10.1023/a:1016430825740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Owen A, Almond L, Hartkoorn R, et al. Relevance of drug transporters and drug metabolism enzymes to nevirapine: superimposition of host genotype. Abstracts of the Twelfth Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 2005; Boston, MA. Abstract 650. http://www.retroconference.org/2005/cd/Abstracts/24878.htm. (29 June 2009, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lamba J, Lamba V, Strom S, et al. Novel single nucleotide polymorphisms in the promoter and intron 1 of human pregnane X receptor/NR1I2 and their association with CYP3A4 expression. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36:169–81. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.016600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siccardi M, D'Avolio A, Baietto L, et al. Association of a single-nucleotide polymorphism in the pregnane X receptor (PXR 63396C→T) with reduced concentrations of unboosted atazanavir. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:1222–5. doi: 10.1086/592304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]