Abstract

Historical reviews suggest that tanning first became fashionable in the 1920s or 1930s. To quantitatively and qualitatively examine changes in tanning attitudes portrayed in the popular women's press during the early 20th century, we reviewed summer issues of Vogue and Harper's Bazaar for the years 1920, 1927, 1928, and 1929. We examined these issues for articles and advertisements promoting skin tanning or skin bleaching and protection. We found that articles and advertisements promoting the fashionable aspects of tanned skin were more numerous in 1928 and 1929 than in 1927 and 1920, whereas those promoting pale skin (by bleaching or protection) were less numerous. These findings demonstrate a clear shift in attitudes toward tanned skin during this period.

NUMEROUS STUDIES HAVE linked exposure to ultraviolet (UV) light to both melanoma1–4 and nonmelanoma skin cancers.2–4 The incidence of skin cancers has risen dramatically over the past century,5–7 and this is largely attributed to increased exposure to UV light from the sun. Despite public education initiatives aimed at preventing skin cancer,8 many individuals continue to tan, citing such reasons as the relationship between tanning and physical and emotional health, an active lifestyle, and physical beauty.9

From a historical perspective, tanning as a fashion trend is a relatively new phenomenon, first noted in the 20th century. Earlier, pale skin was often perceived as a mark of beauty, wealth, and refinement, whereas tanned skin was considered to be typical of manual laborers.10 In the early 20th century, European and American women took precautions to maintain a light skin tone. Parasols and large hats were considered essential summer accessories.11 Magazines in the early 20th century advertised powders that would conceal a tan as well as numerous bleach treatments, such as Bleachine Cream, which was featured in an advertisement by Elizabeth Arden in the July 1, 1920, issue of Vogue as “A mild but effective preparation for removing tan. Nourishing as well as whitening. Excellent for the hands.”12 Toxic lead-based cosmetics, which date back to ancient Roman society, and other types of body powders were commonly used to lighten and augment fair skin during this era.9,13

Although it is well-known that social attitudes changed from sun protection to sun seeking during the first half of the 20th century, the exact year for such a cultural shift has remained obscure. Previous reviews on this subject suggest that the trend began in the late 1920s or early 1930s.10,14 Magazines from the late 1920s reflect a clear shift in attitude, as illustrated in an article from a 1929 issue of Harper's Bazaar: “Shall We Gild the Lily? There Is a Technique to a Good Tan—Whether by Fair Means or Fake!”15

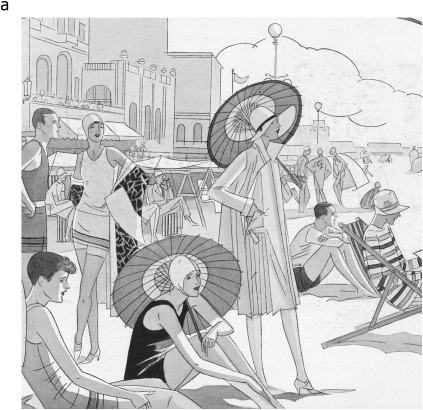

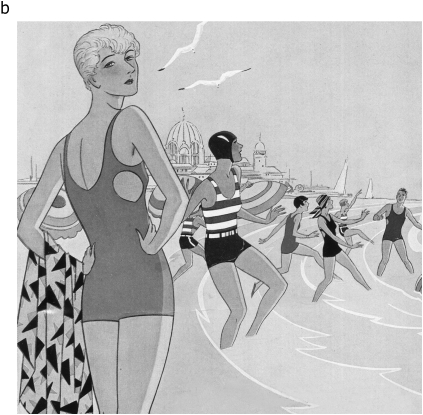

Jantzen swimsuit advertisement from (a) 1927 showing models with sun protection, including shawls, parasols, and wide-brimmed hats, and (b) 1929 depicting models in similar bathing suits, but now frolicking in the sun without sun protection.

Illustrations by Frank Clark. Reprinted with permission of Jantzen.

MAGAZINE REVIEW

To pinpoint the timing of this dramatic cultural shift, we examined the subject matter of all articles and advertisements in multiple 1920s issues of 2 fashion-oriented women's magazines, Vogue and Harper's Bazaar, that targeted populations with high disposable incomes. Several parameters were quantified, including the number of articles that promoted or discussed the benefits of tanned versus pale skin. In addition, advertisements for tanning products versus skin lighteners were counted.

Vogue and Harper's Bazaar were selected for analysis because of their subject matter (women's fashion), popular distribution, and influence in the 1920s. We chose the May, June, and July issues for the years 1920, 1927, 1928, and 1929 because they were most likely to address such seasonal topics as summer fashions, tanning, and protection from the sun. We reviewed each magazine in its entirety and counted articles or advertisements related to tanning, sun protection, skin lightening, or bleaching. In total, we analyzed 24 issues of Vogue (which was published semimonthly) and 12 issues of Harper's Bazaar (published monthly).

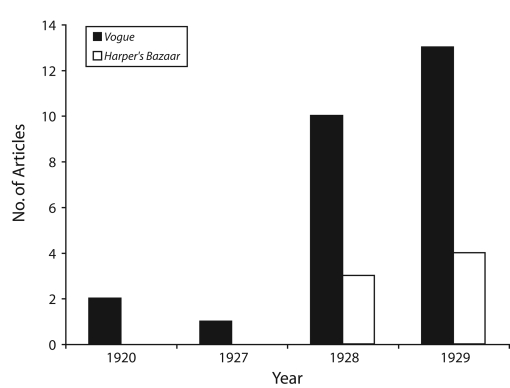

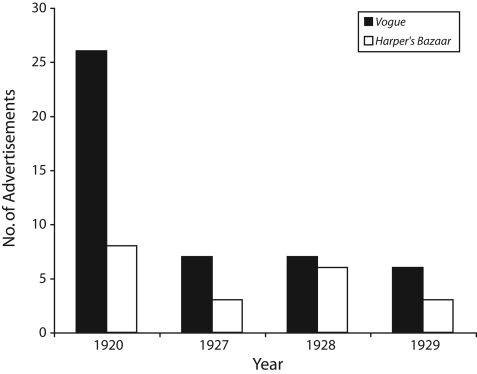

All magazines were examined in their entirety to identify all articles (Figure 1) and advertisements (Figure 2) that favorably described tanned or sunburned skin. These articles and advertisements were categorized as promoting tanned or dark skin. Feature articles written in favor of the fashionable aspects of tanned skin, such as those discussing the new popularity of tanning or the fashions and makeup to wear with tanned skin, were tallied as “articles written specifically about tanned skin,” whereas articles about other subjects with brief mention of the favorable attributes of tanned skin were categorized separately. These 2 counts were then added together to provide the total number of articles promoting tanned skin (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Number of articles advocating skin tanning in the May, June, and July issues of Vogue and Harper's Bazaar for the years 1920, 1927, 1928, and 1929.

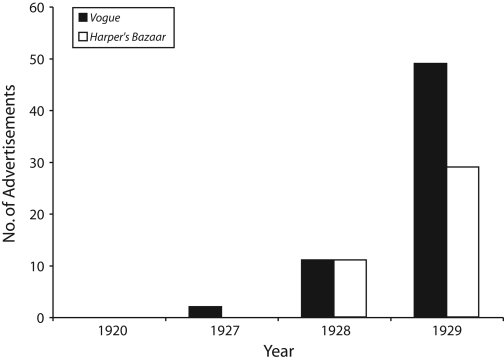

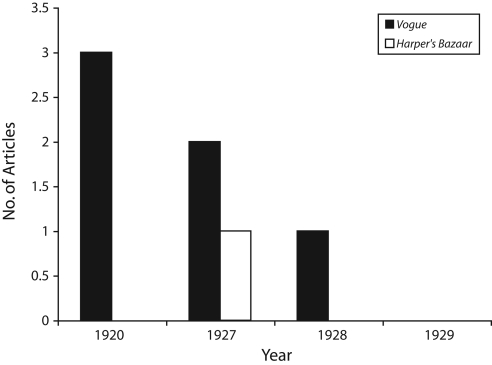

FIGURE 2.

Number of advertisements promoting a tanned appearance in the May, June, and July issues of Vogue and Harper's Bazaar for the years 1920, 1927, 1928, and 1929.

Advertisements for apparel were recorded as “protanning” if the advertisement promoted sun-seeking behavior rather than sun-protective behavior. (This interpretation was based on the text of the advertisement; those that depicted individuals in the sun but did not describe protanning behavior were not included.) Advertisements that cautioned against sunburn but favored tanning were also included as protanning messages. Likewise, advertisements for products intended to mimic or accentuate tans, such as tan-toned stockings or powders, were included as protanning advertisements.

All articles and advertisements promoting lightening of the skin through whitening or bleaching were also recorded, as were those promoting pale skin and sunlight protection (Figure 3).4 Articles and advertisements promoting treatments of specific pigmented dermatologic conditions that are likely to be localized, such as melasma (chloasma) or dyschromia, were excluded.

FIGURE 3.

Number of articles promoting skin bleaching in the May, June, and July issues of Vogue and Harper's Bazaar for the years 1920, 1927, 1928, and 1929.

Differences between raw data are compared in Table 1 (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) and in Figures 1–4. The raw data are clearly and easily presented, and because of the low counts of some of the data, statistical comparisons would have been difficult and potentially misleading.

FIGURE 4.

Number of advertisements for bleaching products in the May, June, and July issues of Vogue and Harper's Bazaar for the years 1920, 1927, 1928, and 1929.

TRENDS IN TANNING ADVERTISEMENTS AND ARTICLES

Beginning in 1928, the number of both articles and advertisements promoting tanning dramatically increased. In the May, June, and July issues for the years 1920 and 1927, the 2 magazines published a total of 3 protanning articles and 2 protanning advertisements; by contrast, in the May, June, and July issues for 1928 and 1929, 30 articles and 99 advertisements were published (Figures 1 and 2).

Over the same period, there was a sharp decrease in the number of articles and advertisements promoting bleached or lightened skin. In May, June, and July of 1920 and 1927, the magazines published 6 articles on skin bleaching as opposed to only 1 during 1928 and 1929. During the same years, collectively, the number of advertisements decreased from 44 to 22. In the magazines examined, there was no single corporate advertiser accountable for this shift in focus (data not shown).

In the May, June, and July 1920 issues of Vogue, there were no articles dedicated to the benefits of tanning, although 2 fashion articles on other subjects briefly mentioned such benefits. Similarly, in the May, June, and July 1927 issues, no articles published in Vogue focused on tanning and only 1 briefly mentioned tanning. By contrast, 2 Vogue feature articles were devoted to the attributes of tanning in 1928, and in the same year, 8 additional Vogue articles had brief mentions of the attributes of tanning (Table 1). The 1928 feature articles encouraged women to tan and described how to dress appropriately to both acquire and display tanned skin. In 1929, eight feature articles were devoted to tanning and 5 articles made reference to fashionable skin tanning. These articles discussed topics such as appropriate cosmetics and attire for tanned skin and instructions for achieving a tan without developing a painful burn.

In the May, June, and July issues of Harper's Bazaar for 1920 and 1927, there were no articles that discussed tanned skin or the benefits of tanning (Table 1). In 1928, there were 2 brief mentions of the new popularity of tanning among fashionable women. In 1929, there was 1 feature article on the proper techniques for achieving a good tan and 2 articles that described fashionable attire for tanning.

There were no advertisements promoting a tanned appearance in 1920 in either Vogue or Harper's Bazaar; in 1927, there were 2 in Vogue but still none in Harper's Bazaar (Figure 2). The number of advertisements promoting a tanned appearance increased notably in 1928, with 11 published in Vogue and 11 in Harper's Bazaar; the number continued to increase in 1929, with 49 appearing in Vogue and 29 in Harper's Bazaar. In 1929, hosiery companies frequently advertised stockings that matched or mimicked tanned skin. Cosmetics companies promoted makeup for tanned skin as well as products that imitated a natural tan. In contrast to earlier trends, by 1929 sportswear and swimsuit companies advertised clothes that allowed for an active lifestyle and exposed skin to the sun for tanning (Figure 2). As an example of the changing attitude demonstrated by advertisements, illustrations from a 1927 advertisement for Jantzen swimsuits featured models protected by shawls, parasols, and hats (Image 1a), whereas in 1929, in a similar scene depicted by the same illustrator, models were exposed to the sun, out from under the protective parasols, exposing their skin to sunlight (Image 1b).

Between the years 1920 and 1929, there was a concomitant trend of decreasing numbers of articles and advertisements on the fashionable benefits of bleached skin. In Vogue, 3 feature articles discussed skin bleaching in 1920 and 2 in 1927, whereas only 1 such article appeared in 1928 and none in 1929 (Figure 3). In Harper's Bazaar, the sole article on bleaching in the 1920s appeared in 1927. A similar decline was observed in advertisements promoting bleaching. Vogue published 23 advertisements promoting skin bleaching products in 1920 but only 7 in 1927, 7 in 1928, and 5 in 1929 (Figure 4). Harper's Bazaar published 8 such advertisements in 1920, 3 in 1927, 6 in 1928, and 3 in 1929.

DISCUSSION

The quantitative analysis of articles and advertisements published in the May, June, and July issues of Vogue and Harper's Bazaar magazines in the 1920s strongly suggests that a marked cultural shift favoring tanning occurred during the period 1927 to 1928. Our data show that there was a sharp increase in the number of articles and advertisements promoting sun tanning or sun-seeking behavior, along with a concomitant decrease in the number of articles advocating sun protection and skin-lightening agents featured in these popular magazines.

In Vogue, only 2 articles about tanning were published in 1920 and 1 in 1927; none were published in Harper's Bazaar during these years. By contrast, in 1928, 10 articles favorably discussed tanning in Vogue and 3 in Harper's Bazaar, and in 1929, there were 13 such articles in Vogue and 4 in Harper's Bazaar (Figure 1).

This trend toward more tanning articles and advertisements in these 2 beauty magazines indicates a cultural shift between 1927 and 1928 favoring sun exposure for the upper middle class and wealthy, fair-skinned White population, the same population that is particularly susceptible to developing skin cancer.2,6,7 The late 1920s precedes the increase in the incidence of melanoma during the mid-20th century (Figure 5; available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org), with the increase continuing throughout the second half of the century.13 Nonmelanoma skin cancer became the most common cancer in the world during the 20th century2,6 Our analysis supports the hypothesis that a change in popular attitude in favor of tanning preceded the melanoma (Figure 5) and nonmelanoma skin cancer epidemic in fair-skinned populations.

For centuries prior to this change in attitude regarding tanned skin, fair skin was considered a mark of beauty and wealth in Western countries. In European literature, references to the beauty of fair skin are myriad, found in tales of “fair maidens” and in the pale skin of painted beauties, including Venus in Botticelli's The Birth of Venus.16 Literature repeatedly scorned sun-darkened skin, as does Beatrice in Shakespeare's Much Ado about Nothing: “I am sunburnt; I may sit in a corner and cry heigh-ho for a husband!”17(p29) This perception of fair skin as a sign of affluence and beauty persisted into the early 20th century, when, for reasons of fashion, women were careful to avoid excessive sun exposure and preserved their fair complexions with parasols, hats, protective clothing, and bleaching products.18,19

Two 1928 Vogue articles specifically addressed the departure from sun protection to the new protanning fashion: “The Sun” and “Vogue's Eye View of the Mode.” These articles specifically described the “baked beaches” that were “black with the recumbent figures of the new sun-worshippers.”20,21 In 1929, the popularity of tanning increased further. An article in Vogue titled “Back to Sunburn With the Mode” promoted tanning in a 4-page spread that described fashion, makeup, and accessories intended to optimally show off tanned skin: “From a chic note, sunburn became a trend, then an established fashion, and now the entire feminine world is sunburn conscious!”22

Similarly, in the June 1929 Harper's Bazaar issue, “Shall We Gild the Lily?” begins a discussion on tanning trends with the statement, “There is no doubt about it. If you haven't a tanned look about you, you aren't part of the rage of the moment.”15 Along with the appearance of occasional advertisements for tanning products,23 the content of these articles supports the conclusion that tanning became a new fashion in 1928.

We found no evidence of a focused fashion or corporate marketing effort related to any one product to explain the sudden change in attitude. As suggested by Segrave,10 in the early 20th century, the medical and scientific communities had started to appreciate the role of sunlight in the treatment of tuberculosis and rickets. It is worth noting that in 1903, Niels Finsen received the Nobel Prize in Medicine24 for his treatment of lupus vulgaris (a form of cutaneous tuberculosis) with heliotherapy. Also in 1903, Auguste Rollier opened the first hospital to treat tuberculosis with sun exposure in Leysin, Switzerland25; heliotherapy remained the most popular treatment of tuberculosis until medicinal tuberculostatic agents became available in 1946.25–27 By 1919, phototherapy had become an established treatment of rickets, and the role of UV light in vitamin D synthesis was discovered during the early 1920s. The 1928 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was given to Adolf Windaus28 for his studies of the structural chemistry of sterols, which contributed to our understanding of vitamin D in treating rickets.

With these discoveries, the medical community of the early 20th century began to promote the use of sunlight as a preventative as well as a therapeutic health measure. Sunlight was thought to prevent tuberculosis in at-risk patients; children were often sent to “preventoriums,” institutions that provided care to sick children in the form of fresh air, food, and exposure to sunlight.29 UV light therapy became widespread both in the United States and Europe, and some physicians began to advocate the use of UV light in treating a diverse array of illnesses, including cardiovascular, oncologic, endocrinologic, atopic, gastrointestinal, rheumatologic, and gynecologic diseases, among others.30

Notably, however, in its 1928 review of the book Ultra-Violet Rays in the Treatment and Cure of Disease, which made some of these claims,31 the editorial staff of the New England Journal of Medicine stated that the book was “an excellent advertising medium for the manufacturers of ultra-violet ray apparatus” and concluded by hoping that the book “does not reach the laity.”32 The editors' hopes were apparently not realized, however, as reflected in Vogue's “The Burning Question of the Summer,” published in 1928:

As a substitute [for the sun] there are the ultra-violet ray lamps that have so cleverly decided to muffle their heat rays and give us only the rays that tan. In addition to these pleasantly modish toasting properties, actinic rays are said to stir up a sluggish skin and do all sorts of desirable things to one's internal functions—reducing colds, stimulating glands, even improving the condition of such totally unexpected things as teeth.33

Although concern was expressed over the role of UV irradiation in skin cancer,34 it was largely ignored at the time. The potential medical benefits of sunlight in the treatment of these diseases appears to have been well-publicized in the popular press and led to the endorsement of sunlight or UV light as a means to treat and prevent a broad range of diseases. It therefore seems apparent that in this era, tanned skin was promoted as a sign of both good health and beauty.

Despite current initiatives to educate the public on skin cancer prevention, substantial numbers of people continue to believe that their appearance is improved with a tan.35,36 A recent study by Knight et al.37 determined that more than 90% of tanning-bed users were knowledgeable of the risks of premature aging and skin cancer but continued to tan for cosmetic reasons. Advertisements continue to promote tanning, even in high school newspapers,38 despite substantial scientific evidence that tanning-bed use correlates with skin cancer.39,40

It is intriguing that the new favorable attitude toward sun tanning occurred shortly before the increases in melanoma incidence (Figure 5). Although the etiologic role of sunlight is not well established for melanoma, its role is clear in nonmelanoma skin cancer, one of the most costly cancers for Medicare and widely believed to be the most common cancer in the world.4,41,42 We believe that this change in attitude may have materially contributed to the dramatic increase in skin cancer rates.

Given the clear scientific evidence regarding the causal role of UV light in nonmelanoma skin cancer and its increasing incidence, there is a need to educate the public regarding the proper amounts of UV light in the context of necessary protective measures. Almost 100 years after the discovery of the attributes of sunlight, health care providers and scientists still dispute whether vitamin D supplementation or UV light exposure is best for proper nutrition and the prevention of rickets.43–45 Mounting evidence, however, indicates that nutritional supplements and dietary intake can provide adequate levels of vitamin D while minimizing the carcinogenic risks associated with UV light exposure.46,47 In 2008, the American Academy of Dermatology issued a statement in support of nutritional sources rather than UV light radiation for adequate levels of vitamin D.46

Medical societies need to collaborate on a unified statement with recommendations on nutrition, vitamin D supplementation, and UV prevention; these societies could include the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Dermatology, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the Endocrine Society, and the American Society for Nutrition. Such consortium statements and recommendations have previously been used to guide other important health care policies, such as exposure to tobacco smoke.48,49 After 100 years of conflicting messages sent from various specialties within the medical community and from the media, it is time to focus rigorous attention on UV light.43–45,50

Our quantitative analysis shows that cultural attitudes shifted dramatically to favor skin tanning for cosmetic reasons during 1928 and that tanning has been a cultural norm in the United States for approximately 4 generations. Unlike 100 years ago, it is now well-established that UV light causes skin cancer. Skin cancer is a major public health concern,6 and proper health care initiatives and policies must be in place to protect future generations from such risks. Understanding the long-term underpinnings of current social attitudes toward sun exposure can facilitate the development of effective public health education initiatives.

Acknowledgments

C. D. Schmults and N. J. Liégeois were supported with Career Development Awards from the Dermatology Foundation.

We thank the Jantzen corporation for authorization to reprint swimsuit advertising images, the Skin Cancer Foundation for allowing adaptation of its Melanoma Letter data, and Maggie Merchant, MD, for critically reviewing this article.

References

- 1.Markovic SN, Erickson LA, Rao RD, et al. Malignant melanoma in the 21st century, part 1: epidemiology, risk factors, screening, prevention, and diagnosis. Mayo Clin Proc 2007;82(3):364–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong BK, Kricker A. The epidemiology of UV induced skin cancer. J Photochem Photobiol B 2001;63(1–3):8–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gallagher RP, Lee TK. Adverse effects of ultraviolet radiation: a brief review. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 2006;92(1):119–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Preston DS, Stern RS. Nonmelanoma cancers of the skin. N Engl J Med 1992;327(23):1649–1662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armstrong BK, Kricker A. Cutaneous melanoma. Cancer Surv 1994;19–20:219–240 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Housman TS, Feldman SR, Williford PM, et al. Skin cancer is among the most costly of all cancers to treat for the Medicare population. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;48(3):425–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jemal A, Devesa SS, Hartge P, Tucker MA. Recent trends in cutaneous melanoma incidence among whites in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001;93(9):678–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jorgensen CM, Wayman J, Green C, Gelb CA. Using health communications for primary prevention of skin cancer: CDC's Choose Your Cover campaign. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 2000;9(5):471–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koblenzer CS. The psychology of sun-exposure and tanning. Clin Dermatol 1998;16(4):421–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Segrave K. Suntanning in 20th Century America Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company Inc; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albert MR, Ostheimer KG. The evolution of current medical and popular attitudes toward ultraviolet light exposure: part 1. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002;47(6):930–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elizabeth Arden advertisement. Vogue July 1, 1920:112 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Randle HW. Suntanning: differences in perceptions throughout history. Mayo Clin Proc 1997;72(5):461–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albert MR, Ostheimer KG. The evolution of current medical and popular attitudes toward ultraviolet light exposure: part 2. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;48(6):909–918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shall we gild the lily? There is a technique to a good tan—whether by fair means or fake! Harper's Bazaar. June 1929:88–89.

- 16.Gombrich E. The Story of Art London, England: Phaidon Press Limited; 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shakespeare W. Much Ado About Nothing New York, NY: Penguin Putnam Inc; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mendes V, De La Haye A. 20th Century Fashion London, England: Thames and Hudson; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warner P. The Americanization of Fashion: Sportswear, the Movies, and the 1930's Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 20.The sun Vogue July 15, 1928:64–65, 102 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vogue's eye view of the mode Vogue June 15, 1928:43 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Back to sunburn with the mode Vogue July 20, 1929:76–78, 98 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glory of the sun [advertisement] Vogue June 8, 1928:158 [Google Scholar]

- 24.The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, 1903. Available at: http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1903. Accessed September 28, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roelandts R. The history of phototherapy: something new under the sun? J Am Acad Dermatol 2002;46(6):926–930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwartz RP. Heliotherapy. Bos Med Surg J 1924;191:243–248 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith M. Historical outline of the Cambridge anti-tuberculosis association 1902–1927. Bos Med Surg J 1927;196: 913–915 [Google Scholar]

- 28.The Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 1928. Available at: http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1928. Accessed September 28, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hawes J. Preventorium problems. Bos Med Surg J 1927;196:807 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Russell EH, Russell WK. Ultra-Violet Radiation and Actinotherapy New York, NY: W. M. Wood and Co; 1927 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hall P. Ultra-Violet Rays in the Treatment and Cure of Disease 3rd ed St. Louis, MO: C. V. Mosby Co; 1928 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ultra-violet rays in the treatment and cure of disease [book review] Bos Med Surg J 1928;199:591 [Google Scholar]

- 33.The burning question of the summer Vogue July 1, 1928:100 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dubreuilh W. Chronic sunburn and epithelioma of the skin. Bos Med Surg J 1925;27:47 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cafri G, Thompson JK, Jacobsen PB. Appearance reasons for tanning mediate the relationship between media influence and UV exposure and sun protection. Arch Dermatol 2006;142(8):1067–1069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robinson JK, Kim J, Rosenbaum S, Ortiz S. Indoor tanning knowledge, attitudes, and behavior among young adults from 1988–2007. Arch Dermatol 2008;144(4):484–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knight JM, Kirincich AN, Farmer ER, Hood AF. Awareness of the risks of tanning lamps does not influence behavior among college students. Arch Dermatol 2002;138(10):1311–1315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Freeman S, Francis S, Lundahl K, Bowland T, Dellavalle RP. UV tanning advertisements in high school newspapers. Arch Dermatol 2006;142(4):460–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berwick M. Are tanning beds “safe”? Human studies of melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 2008;21(5): 517–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ting W, Schultz K, Cac NN, Peterson M, Walling HW. Tanning bed exposure increases the risk of malignant melanoma. Int J Dermatol 2007;46(12): 1253–1257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leiter U, Garbe C. Epidemiology of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer—the role of sunlight. Adv Exp Med Biol 2008;624:89–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manternach T, Housman TS, Williford PM, et al. Surgical treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the Medicare population. Dermatol Surg 2003;29(12):1167–1169; discussion, 1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holick MF. Sunlight, UV-radiation, vitamin D and skin cancer: how much sunlight do we need? Adv Exp Med Biol 2008;624:1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Holick MF, Chen TC. Vitamin D deficiency: a worldwide problem with health consequences. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;87(4):1080S–1086S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gilchrest BA. Sun exposure and vitamin D sufficiency. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;88(2):570S–577S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Position statement on vitamin D Schaumburg, IL: American Academy of Dermatology; June 19, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yetley EA. Assessing the vitamin D status of the US population. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;88(2):558S–564S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parascandola M. Cigarettes and the US Public Health Service in the 1950s. Am J Public Health 2001;91(2):196–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yach D, Wipfli H. A century of smoke. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 2006;100(5–6):465–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scully M, Wakefield M, Dixon H. Trends in news coverage about skin cancer prevention, 1993–2006: increasingly mixed messages for the public. Aust N Z J Public Health 2008;32(5):461–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]