Abstract

Objectives. We examined rates of uninsurance among workers in the US health care workforce by health care industry subtype and workforce category.

Methods. We used 2004 to 2006 National Health Interview Survey data to assess health insurance coverage rates. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to estimate the odds of uninsurance among health care workers by industry subtype.

Results. Overall, 11% of the US health care workforce is uninsured. Ambulatory care workers were 3.1 times as likely as hospital workers (95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.3, 4.3) to be uninsured, and residential care workers were 4.3 times as likely to be uninsured (95% CI = 3.0, 6.1). Health service workers had 50% greater odds of being uninsured relative to workers in health diagnosing and treating occupations (odds ratio [OR] = 1.5; 95% CI = 1.0, 2.4).

Conclusions. Because uninsurance leads to delays in seeking care, fewer prevention visits, and poorer health status, the fact that nearly 1 in 8 health care workers lacks insurance coverage is cause for concern.

For complex socioeconomic reasons, private health insurance, typically provided by an employer, is “the dominant mechanism for paying for health services” in the United States.1(p79) According to the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured and the Urban Institute, analyses of data from the Current Population Survey (CPS) show that, in 2006, 54% of the US civilian, noninstitutionalized population had employer-sponsored health insurance; 5% had private, nongroup health insurance; and 26% had public health insurance coverage. Approximately 46 million US residents (16% of the population) are currently uninsured.2 Numerous studies have shown that, relative to people with health insurance, uninsured people receive less preventive care, are diagnosed at more advanced disease stages, and, once diagnosed, tend to receive less therapeutic care and have higher mortality rates.3–8

Although national uninsurance trends are well-documented, the rate of uninsurance within the health care workforce has received scant attention. Given that health care employment rates are increasing at a more rapid pace than overall employment rates, this lack of attention is especially worrisome. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, nearly half of the 30 occupations in which employment opportunities are growing fastest are health care occupations. For example, whereas the Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that overall employment will increase about 10% from 2006 to 2016, employment opportunities for personal and home care aides are projected to increase nearly 51%, and opportunities for physical therapist assistants are expected to increase by a third. The Bureau of Labor Statistics also projects that, by 2016, new job opportunities for registered nurses will increase by approximately 24% (approximately 587 000 new jobs).9

Although the overall employment outlook for health care workers is promising, what is less clear is to what degree employment in health care is associated with health insurance coverage. A 2001 General Accounting Office report suggested that one fourth of nursing home aides and one third of home health care aides were uninsured.10 The Kaiser Family Foundation reported that the uninsured rate among workers in the health and social services industry was 23% in 2007.11 On the basis of a review of the literature in the health and human services occupations, Ebenstein concluded that the health insurance plans offered to direct care workers in the developmental disabilities field are “inferior … with less coverage and more out-of-pocket expenses” and that fewer direct care workers “are able to afford health coverage even if they are eligible.”12(p132)

Taking a more comprehensive look at the US health care workforce, Himmelstein and Woolhandler13 used 1991 CPS data to estimate uninsurance rates among physicians and other health care personnel. They reported that, overall, 9% of health care workers were uninsured, along with more than 20% of nursing home workers. Examining CPS data from 1988 to 1998, Case et al. found that uninsurance rates among all health care workers rose from 8% to 12%, that rates increased more for health care workers than for workers in other industries, and that rates differed according to occupation and place of employment.14 For example, occupation-specific uninsurance rates were 23.8% among health aides, 14.5% among licensed practical nurses, and 5% among registered nurses, whereas place-specific rates were 20% among nursing home workers, 8.7% among medical office workers, and 8.2% among hospital workers.15

In their studies, Himmelstein and Woolhandler13 and Case et al.14 used national-level data to estimate uninsurance trends among health care workers. However, these trends were not adjusted for health care workers' social, demographic, or economic characteristics, which would have helped explain variation across categories or over time. Moreover, with the growth of the health care workforce, estimates from these older studies probably do not reflect the current situation. As a result, the picture of uninsurance as it pertains to the health care workforce lacks the precision and currentness necessary for sound policy decisions. In an effort to expand knowledge in this area, produce more up-to-date estimates, and provide support for possible policy decisions, we used data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) to examine uninsurance among workers in the health care industry.

METHODS

We assessed the uninsurance status of US health care workers by health care industry subtype and workforce category using NHIS data from 2004 to 2006. With the exception of industry and occupation variables, all of the data used in our study were retrieved from the Integrated Health Interview Series, a Web-based data resource containing harmonized NHIS data from 1969 to the present.15,16 The industry and occupation variables were retrieved from the original NHIS public use files and linked with the Integrated Health Interview Series variables.

Our sample consisted of adults who were aged 20 to 64 years and who reported being employed in the health care industry during the week preceding their interview. We excluded respondents who did not report their occupation or industry and those with missing data with respect to full-time employment status. Data from 2004 to 2006 were pooled to obtain a sufficient sample size of health care workers. Sampling weights were adjusted to account for the pooling of 3 years of survey data. The final, unweighted sample comprised 5192 adults employed in the health care industry.

Measures

Data on all measures were obtained through respondents' self-reports during the in-person NHIS survey. The outcome of interest was health insurance coverage status, dichotomized as “insured” (covered) or “uninsured” (not covered). Respondents were considered insured if they reported being covered by private health insurance, military health insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, the State Children's Health Insurance Program, or another state-sponsored health plan.

To identify health care workers, we used data on the respondents' self-reported main occupation during the week prior to the interview. We classified health care workforce occupations using the 3 categories identified in the NHIS data: health diagnosing and treating occupations (e.g., physicians, nurses), health technicians (e.g., clinical laboratory technologists, licensed practical nurses), and health service workers (e.g., home health aides, medical assistants). We included a residual category for all other workers (e.g., clerks, secretaries). We used the 3 industry subtypes identified in the NHIS data—ambulatory health care services, hospitals, and nursing and residential care facilities—to subdivide the health care industry.

We included a number of additional covariates in our analyses. Self-reported race and ethnicity were combined to create categories representing non-Hispanic Asian, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, and other non-Hispanic (which included American Indian/Alaska Native, multiracial, and any other designation not included in the preceding categories). Age was categorized into 3 groups: 20 to 34 years, 35 to 49 years, and 50 to 64 years. Educational attainment (college degree versus no college degree), marital status (married versus not married), and full-time employment status (either working or not working 35 hours or more a week) were dichotomized. Total income in the preceding year was categorized into 3 groups: less than $20 000, $20 000 to $44 999, and greater than $45 000.

Data Analysis

We examined the extent to which employees in the 3 health care industry subtypes differed in terms of sociodemographic background characteristics potentially associated with insurance coverage; in these analyses, we used cross tabulations and design-based F tests to account for the complex sample design. We used multivariate logistic regression to estimate the odds of uninsurance for health care industry subtypes and workforce categories adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, gender, marital status, education, employment status, and total income. Finally, in the case of each of the 3 health care industry subtypes, we estimated the odds of uninsurance for health care workforce categories with separate logistic regression models adjusted for all of the covariates just mentioned.

We used Stata statistical software, which produces unbiased estimates from data collected through complex sampling designs such as the one used in the NHIS, in conducting all of our analyses.17,18 We produced variance estimates using Taylor series linearization.

RESULTS

Table 1 describes the characteristics of the study population by health care industry subtype. The majority of health care workers were women (78%), White (70%), married (62%), and college educated (74%), and a majority had incomes between $20 000 and $44 999 in the year preceding the survey (42%). Of those employed in the health care industry, 43% worked in ambulatory care, 40% worked in hospitals, and 17% worked in residential care. Approximately 29% of health care workers were in health diagnosing and treating occupations, 12% were health technicians, and 19% were health service workers; nearly 41% were employed in other health care occupations. The majority (78%) of health care workers were employed full time.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Workers in the US Health Care Industry, by Health Care Industry Subtype: National Health Interview Survey, 2004–2006

| Total (n = 5192), % (SE) | Ambulatory Care (n = 2209), % (SE) | Hospital (n = 2038), % (SE) | Residential Care (n = 945), % (SE) | P | |

| Insurance status | <.001 | ||||

| Insured | 89.0 (0.52) | 87.5 (0.8) | 95.8 (0.49) | 76.9 (1.61) | |

| Uninsured | 11.0 (0.52) | 12.5 (0.8) | 4.2 (0.49) | 23.1 (1.61) | |

| Health care industry subtype | |||||

| Ambulatory care | 43.1 (0.86) | … | … | … | |

| Hospital | 39.8 (0.82) | … | … | … | |

| Residential care | 17.1 (0.61) | … | … | … | |

| Workforce category | <.001 | ||||

| Health diagnosing and treating | 29.2 (0.73) | 25.1 (1.13) | 40.9 (1.32) | 12.3 (1.45) | |

| Health technician | 11.5 (0.51) | 11.1 (0.77) | 13.6 (0.9) | 8.0 (1.14) | |

| Health service worker | 18.5 (0.63) | 19.8 (1.0) | 10.6 (0.83) | 33.8 (1.83) | |

| Other | 40.7 (0.77) | 44.0 (1.19) | 34.9 (1.18) | 45.9 (1.91) | |

| Employment status | <.001 | ||||

| Part time | 23.4 (0.72) | 25.5 (1.03) | 20.6 (1.06) | 24.7 (1.75) | |

| Full time | 76.6 (0.72) | 74.5 (1.03) | 79.4 (1.06) | 75.3 (1.75) | |

| Age group, y | <.001 | ||||

| 20–34 | 31.9 (0.86) | 33.0 (1.26) | 30.5 (1.2) | 32.1 (1.89) | |

| 35–49 | 41.8 (0.81) | 42.5 (1.25) | 42.3 (1.22) | 38.8 (1.91) | |

| 50–64 | 26.4 (0.7) | 24.5 (1.06) | 27.2 (1.09) | 29.1 (1.81) | |

| Gender | <.001 | ||||

| Women | 78.1 (0.7) | 76.4 (1.08) | 77.0 (1.12) | 84.7 (1.48) | |

| Men | 21.9 (0.7) | 23.6 (1.08) | 23.0 (1.12) | 15.3 (1.48) | |

| Marital status | <.001 | ||||

| Not married | 37.6 (0.76) | 35.0 (1.2) | 36.8 (1.18) | 46.0 (2.01) | |

| Married | 62.4 (0.76) | 65.0 (1.2) | 63.2 (1.18) | 54.0 (2.01) | |

| Educational attainment | <.001 | ||||

| < College | 25.6 (0.69) | 22.7 (1.01) | 19.0 (1.07) | 48.5 (2.0) | |

| College | 74.4 (0.69) | 77.3 (1.01) | 81.0 (1.07) | 51.5 (2.0) | |

| Race/ethnicity | <.001 | ||||

| Asian, non-Hispanic | 5.0 (0.38) | 4.5 (0.63) | 5.9 (0.58) | 4.2 (0.89) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 15.8 (0.61) | 11.7 (0.77) | 16.0 (0.91) | 25.7 (1.71) | |

| Hispanic | 8.5 (0.41) | 10.4 (0.7) | 6.8 (0.56) | 7.7 (0.98) | |

| Other | 0.5 (0.06) | 0.5 (0.07) | 0.6 (0.12) | 0.2 (0.02) | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 70.2 (0.78) | 72.8 (1.12) | 70.7 (1.15) | 62.1 (2.0) | |

| Past-year income, $ | <.001 | ||||

| < 20 000 | 28.0 (0.79) | 28.2 (1.21) | 20.1 (1.07) | 45.9 (1.98) | |

| 20 000–44 999 | 42.4 (0.84) | 41.2 (1.3) | 43.3 (1.26) | 43.4 (1.95) | |

| > 45 000 | 29.6 (0.79) | 30.6 (1.26) | 36.5 (1.29) | 10.7 (1.36) | |

As can be seen in Table 1, the distribution of workforce categories differed according to health care industry subtype. Health service workers were primarily employed in residential care (34%) and ambulatory care (20%) settings, whereas workers in the health diagnosing and treating occupations were primarily employed in hospitals (41%). Table 1 also shows that the background characteristics of health care workers differed significantly across health care industry subtypes.

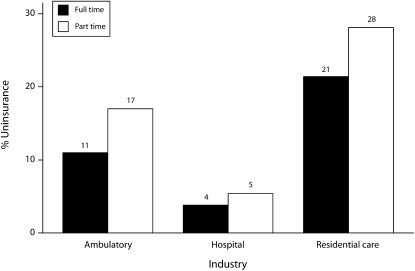

Figure 1 shows uninsurance rates by employment status (full or part time) for the 3 health care industry subtypes. In hospital settings, the difference in uninsurance rates among full-time and part-time workers was nominal. However, there were significant differences between part-time and full-time workers in ambulatory and residential care settings, with uninsurance rates being 6 percentage points higher for part-time ambulatory workers and 7 percentage points higher for part-time residential care workers than for full-time workers.

FIGURE 1.

Uninsurance rates, by employment status and health care industry subtype: National Health Interview Survey, 2004–2006.

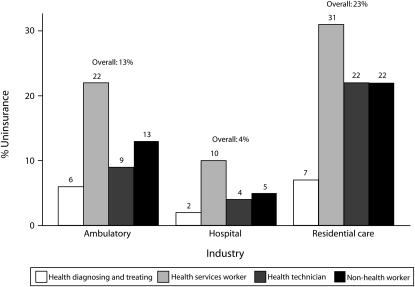

Figure 2 presents uninsurance rates by health care workforce category and health care industry subtype between 2004 and 2006. The rate of uninsurance among all workers aged 20 to 64 years in the health care industry was 11%, significantly lower than the 19% rate among all other workers in the same age range. However, certain workforce categories exceeded the national average uninsurance rate for adults (20%).19 The highest rates of uninsurance were found in residential care settings (23% overall) and among health service workers (22%), regardless of health care industry subtype.

FIGURE 2.

Uninsurance rates, by workforce category and health care industry subtype: National Health Interview Survey, 2004–2006.

Employees in residential care and ambulatory care settings were significantly more likely than those employed in hospitals to be uninsured (rates of 23%, 13%, and 4%, respectively). Relative to workers in health diagnosing and treating occupations, those employed as health technicians, health service workers, or workers in other occupations were significantly more likely to be uninsured. In the case of hospital employees, the rate of uninsurance ranged from 2% among workers in health diagnosing and treating occupations to 10% among health service workers (home health aides and medical assistants). In contrast, rates of uninsurance among workers in residential care settings ranged from 7% (workers in health diagnosing and treating occupations) to 31% (health service workers).

Table 2 summarizes the results from our logistic regression models estimating the adjusted odds of being uninsured among health care workers by workforce category and industry subtype. Ambulatory care workers were nearly 3 times as likely as were hospital workers to be uninsured (odds ratio [OR] = 3.1; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.3, 4.3), and residential care workers were 4.3 times as likely to be uninsured (95% CI = 3.0, 6.1), even after adjustment for workforce category, full-time employment status, and demographic characteristics. After adjustment for covariates, health service workers were 50% more likely than workers in diagnosing and treating occupations to be uninsured (OR = 1.5; 95% CI = 1.0, 2.4).

TABLE 2.

Odds of Uninsurance Among US Health Care Workers, by Health Care Industry Subtype: National Health Interview Survey, 2004–2006

| Total, OR (95% CI) | Ambulatory Care, OR (95% CI) | Hospital, OR (95% CI) | Residential Care, OR (95% CI) | |

| Health care industry subtype | ||||

| Hospital (Ref) | 1.0 | |||

| Ambulatory care | 3.1 (2.3, 4.3)*** | |||

| Residential care | 4.3 (3.0, 6.1)*** | |||

| Workforce category | ||||

| Health diagnosing and treating (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Health technician | 1.1 (0.7, 1.8) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.6) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.8) | 3.8 (1.4, 10.2)** |

| Health service worker | 1.5 (1.0, 2.4)* | 1.4 (0.7, 2.4) | 1.0 (0.4, 2.9) | 2.8 (1.2, 6.6)* |

| Other | 1.0 (0.7, 1.5) | 0.9 (0.9, 2.0) | 0.9 (0.4, 1.8) | 1.8 (0.7, 4.2) |

| Employment status | ||||

| Full time (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Part time | 1.4 (1.1, 1.8)*** | 1.4 (0.9, 2.0) | 1.3 (0.7, 2.4) | 1.4 (0.9, 2.3) |

| Age group, y | ||||

| 20–34 | 1.3 (1.0, 1.7) | 0.8 (0.5, 1.2) | 2.4 (1.1, 5.4)* | 1.9 (1.1, 3.2)* |

| 35–49 | 1.3 (1.0, 1.7) | 1.1 (0.7, 1.6) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.7) | 1.9 (1.2, 3.1)** |

| 50–64 (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Gender | ||||

| Women (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Men | 1.3 (1.0, 1.7) | 1.1 (0.7, 1.8) | 1.2 (0.6, 2.3) | 1.8 (1.0, 3.0)* |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Not married | 2.7 (2.1, 3.4)*** | 3.4 (2.4, 4.7)*** | 1.6 (0.9, 2.8) | 2.6 (1.7, 4.0)*** |

| Educational attainment | ||||

| College (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| < College | 1.6 (1.2, 2.1)*** | 1.7 (1.2, 2.5)*** | 2.5 (1.3, 4.6)** | 1.3 (0.9, 1.9) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Asian, non-Hispanic | 1.6 (0.8, 3.0) | 1.1 (0.4, 2.8) | 1.4 (0.2, 8.0) | 2.6 (1.0, 6.5) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 1.6 (1.2, 2.2)** | 1.5 (0.9, 2.4) | 2.2 (1.2, 4.0)* | 1.5 (1.0, 2.3) |

| Hispanic | 2.6 (1.9, 3.6)*** | 2.5 (1.6, 3.7)*** | 2.3 (1.0, 5.0)* | 3.2 (1.8, 5.8)*** |

| Other | 2.5 (0.8, 7.7) | 1.1 (0.3, 4.1) | 13.3 (3.1, 56.8)*** | 1.5 (0.3, 8.6) |

| White, non-Hispanic (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Past-year income, $ | ||||

| < 20 000 | 4.8 (0.3, 7.5)*** | 5.3 (2.8, 9.8)*** | 5.3 (1.9, 15.2)** | 3.6 (1.2, 10.5)* |

| 20 001–44 999 | 2.1 (1.4, 3.2)** | 2.0 (1.1, 3.5)* | 2.4 (0.9, 5.9) | 1.9 (0.7, 5.3) |

| > 45 000 (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

Note. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

A specific inspection of workforce categories by industry subtypes (Table 2) shows mixed results. In ambulatory care settings, health service workers were twice as likely as workers in health diagnosing and treating occupations to be uninsured. In residential care settings, health technicians and service workers were significantly more likely than workers in health diagnosing and treating occupations to lack health insurance. For instance, with respect to workers employed in residential care settings, health technicians were nearly 4 times as likely as were those in health diagnosing and treating occupations to be uninsured, and health service workers were nearly 3 times as likely to be uninsured. By contrast, comparisons of workforce categories showed no significant differences among workers in hospital settings in terms of likelihood of being uninsured.

DISCUSSION

Our study provides a national-level description of uninsurance among the US health care workforce by health care industry subtype and workforce category. Our results show that disparities in uninsurance rates exist in the health care workforce and that these disparities differ significantly according to industry subtype and workforce category. For example, people working in ambulatory care and residential care settings were more likely to be uninsured than were those working in hospital settings. Our findings are consistent with those of earlier studies documenting higher uninsurance rates among health care workers employed in practitioners' offices and nursing homes than among those employed in hospitals.13,14

One reason for this disparity may be that in many cases companies in the ambulatory care and residential care industries are smaller than hospitals.20 Previous studies have indicated that a firm's size is related to the likelihood of an employee being insured, with employees in small firms less likely than employees in large firms to be covered by employer-based health insurance.21–24

In addition, health care workers in nursing homes and residential settings earn lower wages, a factor associated with higher rates of uninsurance.25,26 According to the BLS, mean hourly wages in 2007 were $10.03 for home health aides and $11.14 for nurse aides, orderlies, and attendants; mean hourly wages for registered nurses in hospital and residential settings were $30.69 and $27.12, respectively.27–29 By contrast, the mean hourly wage in 2007 for physicians was more than $70 per hour.30 Most low-income workers cannot afford health insurance premiums and copayments, even when coverage is offered by their employer.12,31,32 On the basis of a review of studies on characteristics of direct care workers and the wages and health insurance benefits available, Stone reported that most home care workers earning low incomes cannot afford health insurance.31

Our analyses also demonstrate that uninsured health care workers are more likely to be part-time employees, young, unmarried, Black, or Hispanic; to have less than a college education; and to have lower incomes. These findings are consistent with those of other studies investigating the characteristics of people most likely to be uninsured.6,21,33,34

There is also evidence supporting concerns that the health and well-being of uninsured workers in the health care industry may be at risk. According to Hadley and Reschovsky,21 uninsured individuals are less likely to receive preventive and therapeutic care, thereby increasing their risk of poor health. Moreover, Chou and Johnson, in a study examining health status and obesity prevalence in various health care worker categories, found that individuals employed as health technicians or health service workers were more likely to report poor health and to be obese than were those employed in health diagnosing occupations.35

Because poor health and obesity are often linked to a lack of health insurance coverage or inadequate coverage, and because our results demonstrate that the rate of uninsurance among health care service workers is relatively high, the natural question to ask is whether these factors are causally linked. Does the relatively high rate of uninsurance cause the high rates of obesity and poor health among some classes of health care workers? Although we did not directly address this question, our findings suggest that additional research on health insurance coverage, health care use, and health outcomes among health care workers is warranted.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, our measure of uninsurance was a point-in-time measure representing individuals' self-reported lack of insurance coverage at the time of their interview. Among those lacking health insurance coverage, we had no additional information regarding whether employer-sponsored insurance was offered but declined or simply was not offered. Similarly, employment-related information was ascertained relative to respondents' employment in the week preceding the interview. Thus, our estimates represent only a snapshot of uninsurance in the health care workforce.

Second, the health care industry subtypes and workforce categories in our analyses were broadly defined. We were limited to the 3 health care industry subtypes identified in the NHIS data. Moreover, the NHIS does not release detailed occupation categories and has combined physicians and nurses in the same group since 2005. Thus, our use of these coarsened health care workforce categories may have masked important disparities in uninsurance within each category. Third, the public use data of the NHIS lack state-level identifiers, prohibiting us from analyzing or controlling for state-level health care infrastructure and health policy differences.

Policy Implications

Our study raises some important and perhaps alarming issues about the health care workforce in the United States. In some settings, specifically residential care and nursing homes, almost one third of all workers providing hands-on care to vulnerable adults are uninsured. There are several implications of these findings, including concerns about workers transmitting undetected infectious disease because they delay seeking care and transmitting the flu because they do not receive a flu shot; moreover, poor health status and obesity among these workers could result in an increased number of lost workdays caused by illness, contributing to high turnover rates in nursing homes.

Hospitals fare better in providing their workforce with insurance coverage, possibly because they pay higher wages and because they need to attract a highly skilled workforce. Even in hospitals, however, an average of 10% of service workers lack health insurance coverage.

There are currently no regulations stipulating that health care providers offer health insurance coverage to their workers or requirements that they do so. Health care providers are considered similar to other employers and are treated as such by federal and state regulations. Yet, the type of service they provide and the dependency of patients on their care providers for appropriate and safe care do make them distinct.

Some states have pursued policies to address the high rates of uninsurance among health service workers, primarily through the Medicaid program, which currently pays almost half of the wages and benefits of caretakers. For example, Minnesota passed legislation requiring that a certain amount of each increase in the Medicaid payment rate be directed toward health insurance coverage of health service workers.36 In addition, Michigan passed legislation requiring that nursing homes devote a specific amount of existing state funds to wage increases and benefit improvements.36

States might also consider other financial incentives in their nursing home payments that are directly targeted to health insurance coverage. Given concerns about infectious diseases, new resistant bacterial strains, and the quality and safety of our health care institutions, it is essential that the people working directly in these settings receive needed health care services, including recommended immunizations and primary and preventive care.

Conclusions

Our analyses demonstrate that disparities in uninsurance exist in the US health care workforce and that these disparities differ significantly according to health care industry subtype and workforce category. Because the future of US health care depends on the support and development of a quality health care workforce, the fact that nearly 1 in 8 people in the US health care workforce lacks insurance coverage is a cause for concern.

Creating policies specifically aimed at ensuring that health care workers are adequately insured will not only help workers themselves but also promote the health of those they serve. Of course, knowing that a problem exists is not the same as knowing why the problem exists, and effective health policies require both kinds of information. For this reason, further research, building on the results described here, is needed to understand the determinants of the disparities in uninsurance that exist in the US health care workforce.

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was needed for this study.

References

- 1.Smith DG. The uninsured in the U.S. health care system. J Healthc Manag 2008;53:79–81 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured Health coverage in the U.S., 2006. Available at: http://facts.kff.org/chart.aspx?ch=477. Accessed August 27, 2009

- 3.Institute of Medicine Care Without Coverage: Too Little, Too Late. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine The Uninsured Are Sicker and Die Sooner. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute of Medicine Coverage Matters: Insurance and Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ayanian JZ, Weissman JS, Schneider EC, Ginsburg JA, Zaslavsky AM. Unmet health needs of uninsured adults in the United States. JAMA 2000;284:2061–2069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pagán JA, Asch DA, Brown CJ, Guerra CE, Armstrong K. Lack of community insurance and mammography screening rates among insured and uninsured women. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:1865–1870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hadley J. Sicker and poorer—the consequences of being uninsured: a review of the research on the relationship between health insurance, medical care use, health, work, and income. Med Care Res Rev 2003;60(suppl 2):3S–75S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dohm A, Shniper L. Occupational employment projections to 2016. Mon Labor Rev 2007;30:86–125 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Health Workforce: Ensuring Adequate Supply and Distribution Remains Challenging. Washington, DC: US General Accounting Office; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured The uninsured: a primer. October 15, 2008. Available at: http://www.kff.org/uninsured/7451.cfm. Accessed August 27, 2009

- 12.Ebenstein W. Health insurance coverage of direct support workers in the developmental disabilities field. Ment Retard 2006;44:128–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S. Who cares for the care givers? Lack of health insurance among health and insurance personnel. JAMA 1991;266:399–401 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Case BG, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S. No care for the caregivers: declining health insurance coverage for health care personnel and their children, 1988–1998. Am J Public Health 2002;92:404–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson PJ, Blewett LA, Ruggles S, Davern ME, King ML. Four decades of population health data: the Integrated Health Interview series. Epidemiology 2008;19:872–875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Minnesota Population Center Integrated Health Interview Survey. Available at: http://www.ihis.us/. Accessed August 27, 2009

- 17.Stata Statistical Software [computer program]. Version 9.0 College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Survey Data Reference Manual. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaiser Family Foundation Uninsured rates among adults by state, 2005–2006. Available at: http://facts.kff.org/chart.aspx?ch=357. Accessed August 27, 2009

- 20.Bureau of Labor Statistics Career guide to industries, 2008–2009. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/oco/cg/cgs035.htm Accessed August 27, 2009

- 21.Hadley J, Reschovsky JD. Small firms' demand for health insurance: the decision to offer insurance. Inquiry 2002;39:118–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fronstin P, Helman R. Small Employers and Health Benefits: Findings From the 2002 Small Employer Health Benefits Survey. Washington, DC: Employee Benefit Research Institute; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morrisey M, Jensen G, Morlock RJ. Small employers and the health insurance market. Health Aff 1994;13:149–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fronstin P. Sources of Health Insurance and Characteristics of the Uninsured: Analysis of the March 2004 Current Population Survey. Washington, DC: Employee Benefit Research Institute; 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lipson D, Regan C. Health insurance coverage for direct care workers: riding out the storm. Available at: http://www.bjbc.org/content/docs/BJBCIssueBriefNo3.pdf?pubid=22. Accessed August 27, 2009

- 26.Yamada Y. Profile of home care aides, nursing home aides and hospital aides: historical changes and data recommendations. Gerontologist 2002;42:199–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bureau of Labor Statistics Occupational employment statistics: home health aides. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes311011.htm#nat. Accessed August 27, 2009

- 28.Bureau of Labor Statistics Occupational employment statistics: nursing aides, orderlies, and attendants. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes311012.htm. Accessed August 27, 2009

- 29.Bureau of Labor Statistics Occupational employment statistics: registered nurses. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes291111.htm. Accessed August 27, 2009

- 30.Bureau of Labor Statistics Occupational employment statistics: physicians and surgeons, all others. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes291069.htm. Accessed August 27, 2009

- 31.Stone RI. The direct care worker: the third rail of home care policy. Annu Rev Public Health 2004;25:521–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chernew M, Frick K, McLaughlin CG. The demand for health insurance coverage by low-income workers: can reduced premiums achieve full coverage? Health Serv Res 1997;32:453–470 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Long SH, Rodgers J. Do shifts toward service industries, part-time work, and self-employment explain the rising uninsured rate? Inquiry 1995;32:111–116 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harrell J, Carrasquillo O. The Latino disparity in health coverage. JAMA 2003;289:1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chou CF, Johnson PJ. Health disparities among America's health care providers: evidence from the Integrated Health Interview Series, 1982 to 2004. J Occup Environ Med 2008;50:696–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Service Employees International Union A crisis for caregivers: health insurance out of reach for nursing home workers. Available at: http://www.directcareclearinghouse.org/download/Crisis%20for%20Caregivers%20-%20NH%20Insurance.pdf. Accessed August 27, 2009