Abstract

Objectives

A number of case reports have been published describing a possible association between isotretinoin (Accutane) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). We critically appraised the published literature on this association to assess whether the current literature supports a causal relationship between isotretinoin and IBD.

Methods

We systematically searched the literature for case reports, case series, and clinical trials assessing the association between isotretinoin and IBD. We then applied the nine Bradford Hill criteria in order to evaluate causality of this association.

Results and discussion

We identified 12 case reports and 1 case series that reported an association between isotretinoin use and subsequent development of IBD. Cases occurred in 7 different countries over a 23 year time period (1986 to 2008). Cases differed with respect to dose of isotretinoin reported, duration of treatment prior to development of disease, whether disease developed on or off medication, and clinical presentation of disease. To date, no prospective or retrospective case control or cohort studies have examined the relationship between isotretinoin exposure and the outcome of IBD. An estimated 59 coincident cases of IBD would be expected in Accutane users each year, assuming no increased risk. Application of the Bradford-Hill criteria reveals that the temporality criterion of causation is fulfilled, though a number of alternative explanations may account for the observed sequence of events seen in case reports. Strength, specificity, and consistency of the association are lacking.

Conclusions

Current evidence is insufficient to confirm or refute a causal association between isotretinoin and IBD. Additional prospective or well-designed retrospective (e.g. case-control) pharmacoepidemiologic studies are needed to definitively establish causality.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease, Ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, Isotretinoin, Accutane, Acne, Epidemiology, Causal inference, Bradford-Hill criteria

Introduction

In a recent court case in New Jersey, a jury awarded $12.9 million to three patients who were diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) after being treated with the acne medication Accutane (isotretinoin). A number of similar multimillion dollar lawsuits preceded this one. Accutane was FDA-approved for the treatment of severe recalcitrant nodular acne in 1982 by Roche. Subsequently, a number of case reports of this association were published in the post marketing period(1-6), and the development of IBD is now listed as a warning in the package insert for Accutane(7). In addition to individual case reports, Reddy et al. have recently published a review of the FDA MedWatch reports of IBD cases occurring in association with isotretinoin use(8). Although the possibility that isotretinoin may predispose to the development of IBD is a cause for serious concern, the published case reports and case series, as well as related court decisions must be interpreted with caution.

Case reports are essential in identifying possible adverse drug reactions and are thus “hypothesis-generating.” However, such reports are subject to a number of flaws, including recall bias, publication bias, incomplete and subjective presentation of case details (by both patients and physicians), and lack of follow-up. Because of such biases, case reports may lead readers to assume causation and to overestimate the risks in similar patients and the population at large.

In order to evaluate the whether the reported association between isotretinoin and IBD is causal, we first searched the published literature to identify all relevant papers and case reports. Next, we performed a critical appraisal of this literature using the criteria developed by Sir Austin Bradford-Hill to evaluate whether the relationship between two factors might be causal. The Bradford-Hill criteria, first established in 1965, are comprised of nine components: strength, consistency, specificity, temporality, biologic gradient, plausibility, coherence, experimental evidence, and analogy(9). While the presence or absence of any one criterion is insufficient to confirm or refute causality, when an association fulfills a preponderance of these criteria, a case for an etiological connection can be made.

Summary of case reports

Twelve case reports (1-6, 10-15) and 1 case series (16) were identified via a systematic search strategy. Results are summarized in Table 1. In total, 15 cases were reported in 7 different countries over a 23 year time period (1986 to 2008). In addition, there were 85 cases reported in the FDA MedWatch analysis from 1997 to 2002(8). Cases developed at a range of doses (20mg–80mg per day), and several of the cases were diagnosed after therapy with isotretinoin had been discontinued(2, 5, 14, 16). Two cases resolved after Accutane was discontinued(12, 15). Five of the individual case reports did not report a definitive diagnosis of IBD (11-15).

Table 1.

Summary of case reports and case series identified by systematic literature search*

| Author(ref) | Year | Location | N | Age, gender |

Dose of Accutane |

Length of Accutane treatment |

Manifestation | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case reports | ||||||||

| Spada(15) | 2008 | Italy | 1 | 22 M | 40mg/d | 15 d | Pan-enteritis | Patient developed inflammation of the stomach, jejunum, and sigmoid colon. Symptoms resolved after isotretinoin d/c. |

| Rolanda(6) | 2007 | Portugal | 1 | 19 F | 20mg/d | 12 mo | CD | Patient was being treated with isotretinoin for acne inversa, a possible extra-intestinal manifestation of CD. |

| Ahmed(1) | 2006 | US | 1 | 15 M | NR | NR | UC | Gastrointestinal symptoms occurred with prior prescription of isotretinoin 6 months prior to UC diagnosis |

| Bankar(2) | 2006 | India | 1 | 26 M | 80mg/d | 5 mo | UC | Case developed 1 mo after isotretinoin d/c |

| Mennecier(4) | 2005 | France | 1 | 32 F | 45mg/d | 4 mo | UC | Patient had been treated with isotretinoin 10 years prior for 5 months without complications |

| Moneret- Vautrin(14) |

2005 | France | 1 | 26 M | 0.5mg/kg/d | 7 mo | Collagenous colitis | Case diagnosed 4.5 years after isotretinoin d/c |

| Borobio(3) | 2004 | Spain | 1 | 18 F | 30mg/d | 4.5 mo | UC | |

| Melki(13) | 2001 | France | 1 | 27 M | 40mg/d | 2 mo | Granulomatous colitis | Symptoms began shortly after increasing dose from 30mg/d to 40mg/d. Patient had developed non-bloody diarrhea upon treatment with isotretinoin 2 years previously |

| Reniers(5) | 2001 | Canada | 1 | 17 M | NR | 5 mo | UC | Case developed 1 week after isotretinoin d/c |

| Deplaix(11) | 1996 | France | 1 | 18 M | NR | 3 mo | Hemorrhagic colitis | |

| Martin(12) | 1987 | US | 1 | 17 M | 40mg/d | 1 mo | Undetermined proctosigmoiditis |

Symptoms began shortly after increase in dose from 20mg/d to 40mg/d. Proctosigmoiditis resolved upon withdrawal of isotretinoin. |

| Brodin (10) | 1986 | US | 1 | 26 F | 60mg/d | 9 d | Proctitis | Symptoms worsened after d/c isotretinoin |

| Case series | ||||||||

| Passier(16) | 2006 | Netherlands | 3 | 19 M 17 M 17 M |

60mg/d 60mg/d NR |

5.5 mo 6 mo 6 mo |

UC CD UC |

Case developed 1.5 mo after isotretinoin d/c Case developed 6 mo after isotretinoin d/c Case developed 3 mo after isotretinoin d/c |

| FDA reports | ||||||||

| Reddy(8) | 2006 | US | 85 | Median: UC: 18 CD: 19 |

Median: 40mg/d |

NR | UC: 36/85 (42%) CD: 30/85 (35%) “Other”: 19/85 (22%) |

Summary of FDA MedWatch reports from 1997–2002 includes 2 cases with previous history of IBD. The number of cases reported may contain some cases reported elsewhere. |

We searched the Medline indexed literature via PubMed using keywords “Accutane”, “isotretinoin”, “inflammatory bowel disease”, “ulcerative colitis”, “Crohn’s disease”, and “colitis”. Additionally, we hand-searched the reference lists of identified articles for additional relevant publications. We also searched BIOSIS Previews for relevant scientific meeting abstracts using the same keywords above. Any study of inflammatory bowel disease (loosely defined as ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, or other colitis) in persons taking isotretinoin or with a past history of isotretinoin use were included, as long as original data were reported. We included case reports or case series, cohort studies, case control studies or other retrospective analyses, and letters to the editor. We did not restrict results based on language of publication.

UC: ulcerative colitis; CD: Crohn’s disease; NR: Not reported; d/c: discontinued; mo: months, d: days; M: male; F: female

Causal criteria

1) Strength

Strength is defined by the size of the association as measured by appropriate effect measures (risk difference, relative risk, odds ratio, or equivalent). The stronger the association, the more likely a relationship is causal. No published observational or interventional studies have adequately measured the strength of the association between isotretinoin and IBD in a quantitative way.

Case reports and case series include only individuals that had both the exposure (isotretinoin) and outcome (IBD). Additional data are required to estimate the strength of exposure-outcome relationships. Specifically, the number of individuals treated who did not develop the outcome, and the baseline incidence of disease in untreated individuals are needed to calculate measures of effect such as risk ratios or odds ratios.

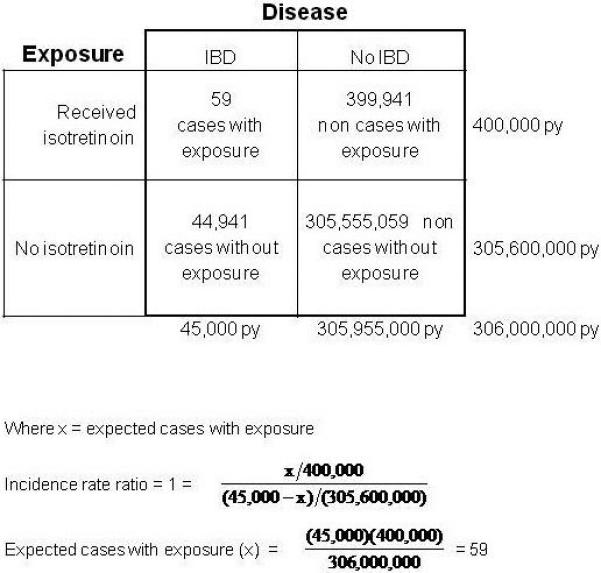

Despite the incomplete data, it is instructive to estimate the strength of this potential association using population-based estimates of isotretinoin use and IBD incidence to complete the missing cells of a traditional 2×2 table (Figure 1). Assuming 1) a background incidence of IBD in the US of approximately 45,000 cases per year(17, 18) 2) the number of persons taking isotretinoin is approximately 400,000 per year(19), and 3) the total US population is approximately 306 million(20), the expected number of cases of IBD among isotretinoin users would be 59 cases per year (if there were no association between isotretinoin and IBD), or 0.01% of Accutane users. If more than 59 cases per year were observed in isotretinoin users, this would suggest a positive relationship between isotretinoin use and IBD. However FDA MedWatch reports include an average of only 14 cases per year(8). Although MedWatch reports are certainly subject to under-reporting (21),the published number of cases do not support a strong association.. Importantly, this exercise demonstrates that a certain number of cases of IBD are likely to develop in isotretinoin users simply on the basis of chance. It is possible, therefore, that the cases reported in the literature might simply be reflecting the chance co-incidence of IBD and isotretinoin.

Figure 1.

A hypothetical cohort study of the entire US population is represented in this model 2×2 table. The time period at risk is 1 year. Equal rates of IBD in both exposed persons (“received isotretinoin”) and unexposed persons (“No isotretinoin”) would correspond to an incidence rate ratio of 1 (i.e. no causation). We made assumptions about the annual incidence of IBD, the number of persons exposed to isotretinoin per year, and the size of the US population using the best available data. We then calculated the expected number of new cases of IBD per year in those taking isotretinoin assuming no causation (calculation below). The number of cases per year in those taking isotretinoin would have to be greater than 59 in order to support a causal association.

Where x = expected cases with exposure

IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; py: person years

If isotretinoin use is more common in IBD sufferers, that would also contribute to the strength of the association. Though no case control studies have been performed examining this relationship, one retrospective study of 306 IBD cases in Italy failed to demonstrate any prior exposures to isotretinoin.(22)

2) Consistency

Consistency refers to whether the observed association has been repeatedly observed in different persons and different settings. For example, at the time that Hill established thesecriteria, there were a total of 29 retrospective and 7 prospective reports describing the association between smoking and lung cancer, each reaching the same conclusion irrespective of study design. Consistency provides reassurance that the association is not due to chance or systematic bias.

Though multiple case reports of this association have been published in various geographic areas, a consistent pattern of disease occurrence has not emerged. Case reports differ with regards to duration of treatment, lag time between initiation of treatment and development of disease, whether symptoms developed on or off therapy, and clinical features of disease. However, as discussed above, the association between isotretinoin and IBD has not been adequately measured in any studies; therefore, consistency of effect measures is impossible to establish at this point in time.

3) Specificity

Specificity refers to whether an exposure leads to a specific outcome. For example, the link between the diet drug combination phentermine/fenfluramine and valvular heart disease in young women fulfills this criterion. In contrast, isotretinoin has protean effects(23) including teratogenicity, effects on bone mineral density, hearing and visual disturbances, and depression..

Furthermore, both CD and UC have been reported with regards to this association, with comparable frequency. It is well recognized that CD and UC are distinct clinical entities that differ with respect to disease activity, pathology, and (presumptively) etiopathogenesis. Other forms of colitis have also been reported including granulomatous colitis(13), and collagenous colitis(14). The fact that one exposure has been linked to several outcomes indicates lack of specificity. Nevertheless, specificity is considered the weakest of all the Hill’s criteria. Indeed, tobacco has been demonstrated to cause a number of diseases, and illnesses such as lung cancer have multiple predisposing factors in addition to smoking. Thus, the absence of specificity does not preclude a causal relationship.

4) Temporality

In a temporal relationship, the cause (i.e. isotretinoin) must precede the outcome (i.e. onset of IBD). Such a temporal relationship supports, but does not confirm, a causal relationship. However, lack of a temporal relationship clearly refutes causality: an exposure that occurs after the onset of disease clearly did not cause the disease.

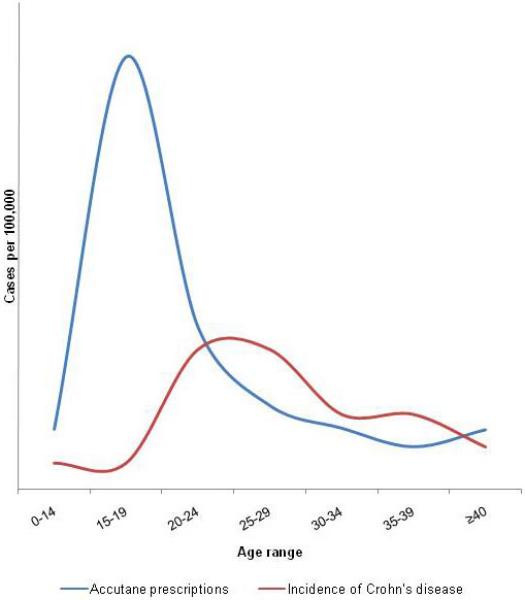

Taken at face value, a temporal relationship exists between isotretinoin use and IBD onset, as evidenced by the numerous case reports and case series. However, we propose several, non-causal explanations for the observed temporal relationship. First, the association may be due to confounding based on age. The peak age of IBD occurrence is in early adulthood, while the peak age of isotretinoin use is age 13–24 (Figure 2)(19). Therefore, in the absence of causation, most cases of IBD developing in persons who also have acne and are prescribed Accutane will occur in this order.

Figure 2.

Graph of the peak ages of isotretinoin prescriptions and incidence of Crohn’s disease demonstrating the normal temporal sequence of development of IBD in Accutane users, and evidence for confounding based on age as an explanation for the temporal association between drug and disease.

Figure based on data from Loftus et al., Gastroenterology 1998;114(6) 1161-8 (17) and Wysowski et al., J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 46(4) 505-9 (19)

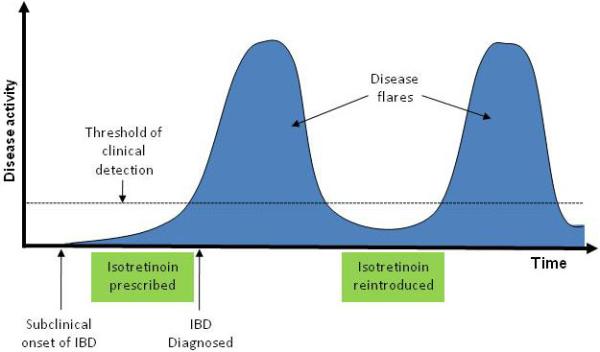

In addition, the biological onset of IBD and initial symptoms often occur 1 year (or longer) prior to diagnosis. Therefore, as has been suggested by other authors(6, 8), it is possible in some cases that although disease diagnosis may have occurred after exposure to isotretinoin, the disease onset may actually have preceded isotretinoin therapy (i.e. isotretinoin was given to persons with sublinical IBD)(Figure 3). We must also consider the possibility of reverse causation: that IBD resulted in exposure to isotretinoin. Pyoderma faciale is a dermatologic condition that may mimic severe acne, but is in fact a known extra-intestinal manifestation of IBD that may precede its diagnosis (Figure 4)(24). Neutrophilic dermatoses such as Sweet’s syndrome may also associated with IBD(25). It is possible that some cases of this association occur in patients who’s underlying IBD (as manifested by these acne-like skin conditions) preceded isotretinoin use, and thus the observed temporal relationship was inverted.

Figure 3.

Diagram of a possible non-causal sequence of events leading to an observed temporal relationship between isotretinoin use and inflammatory bowel disease. Because of delays in the initial diagnosis of IBD, subclinical onset of disease may precede the initial prescription of isotretinoin. If isotretinoin is discontinued when IBD is initially diagnosed, and reintroduced when disease activity is quiescent, subsequent flares of disease typical of the natural history of IBD could be mistaken for effects of re-exposure to the drug.

IBD: inflammatory bowel disease

Figure 4.

Appearance of pyoderma faciale, an extraintestinal manifestation of inflammatory bowel disease that may mimic acne.

Reprinted with permission from Cutis. 2008;81:488-490. ©2008, Quadrant HealthCom Inc.(39)

Another component of temporality includes whether the adverse event abates after withdrawal of medication and recurs with reintroduction of medication. This pattern has been observed in some case reports(12), however, it is difficult to interpret for a relapsing and remitting condition such as IBD. The natural course of the disease may be mistaken for results of reintroduction and withdrawal of isotretinoin. Also, the observation that symptoms resolve upon discontinuation of isotretinoin therapy, in most cases, would be complicated by concomitant initiation of IBD therapy (e.g. corticosteroids), another example of confounding. Furthermore, the observation that symptoms return upon reintroduction of isotretinoin is complicated by the fact that reintroduction is likely to occur during periods of disease remission. Based on the natural history of the disease itself, independent of any effects of isotretinoin, some of these patients will experience a recurrence of symptoms (Figure 3).

5) Biologic gradient

The biologic gradient criterion refers to whether a dose-response relationship is present: if an increasing dose of the exposure corresponds to an increase in incidence and/or severity of effects, this supports a causal relationship. For example, acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity fulfills this criterion, with higher doses corresponding to worsened risk of liver failure. Evidence of a biological gradient is supported by 3 cases of persons who were diagnosed with IBD shortly after increasing their dose of isotretinoin (8, 12, 13). However, there are also case reports of this association in persons taking relatively low doses of isotretinoin (20 mg/day(6) and 30 mg/day(3)), as well as in patients who had discontinued isotretinoin prior to the presentation of IBD(2, 5, 14, 16). Interestingly, an early study of Accutane’s adverse effects demonstrated an inverse dose-response relationship with regards to gastrointestinal symptoms(23). Therefore, at this point in time, the evidence of a biological gradient is inconclusive.

6) Plausibility

This refers to whether the observed association is biologically plausible. Given that the etiology of IBD is largely unknown, it is difficult to assess the plausibility of isotretinoin as a trigger of IBD. In fact, the mechanistic studies that are available in the published literature could support a beneficial effect of vitamin A derivatives in regards to the development and perpetuation of IBD. For example, a key factor implicated in the pathogenesis of IBD is impaired barrier function of the intestinal epithelium. Retinoic acid, a form of vitamin A, has been shown to enhance barrier function by increasing expression of numerous tight junction proteins such as occludin, claudin-1, claudin-4, and zonula occludens-1(26). Furthermore, from the standpoint of immune function, retinoic acid has been shown to be capable of inhibiting pro-inflammatory interleukin-17-producing T helper cell (Th17) responses, while augmenting anti-inflammatory regulatory T cell induction(27). Such responses would be more likely to prevent the development of IBD, as opposed to trigger it. Nevertheless, retinoids have pleiotropic effects, including natural killer T-cell stimulation, B-cell differentiation, disruption of glycoprotein synthesis and epithelial tissue growth, apoptosis, and alteration of cytokines (12, 28, 29). Therefore, though speculative, the association between isotretinoin and IBD remains biologically plausible, though beneficial effects could be postulated as well.

7) Coherence

This principle states that a causal relationship should not contradict the known facts of the natural history and biology of the disease in question. One threat to coherence is that several reports have been published of use of isotretinoin in patients with known pre-existing IBD who did not experience exacerbations of disease(30-35); if isotretinoin causes IBD, we might expect that exposure could also lead to flares of known disease. Furthermore, while the number of prescriptions for Accutane in the US rose rapidly in the 1990s(19), rates of IBD have remained relatively constant during the same time period(18, 36). However, as there are many unknowns regarding the etiology and pathophysiology of IBD, a causal association would be difficult to refute on the basis of lack of coherence.

8) Experimental evidence

This criterion refers to whether evidence in humans or other species exists to corroborate the connection. No human experiments have addressed this question, and we were unable to find published evidence of colitis developing in animals exposed to isotretinoin or similar compounds. Experimental evidence also refers to whether the outcome can be prevented or ameliorated by an appropriate experimental regimen. Since the mechanisms of isotretinoin are largely unknown and no single ‘antidote’ exists, such experiments are not possible.

9) Analogy

Analogy refers to the effect of similar factors. There are no known medication triggers of IBD from which to draw analogies, and no other retinoid compounds have been linked to IBD. Nor can analogies be drawn from isotretinoin’s proposed mechanisms of acne amelioration (inhibition of sebaceous gland function and keratinization)(37) and teratogenicity (impaired cephalic neural-crest cell activity)(38), which seem distinct from the putative mechanism(s) of IBD, which involves disruption of bowel mucosa integrity and induction of autoimmunity.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the only evidence to support a causal association between Accutane and IBD consists of isolated case reports. These reports support a possible temporal association between isotretinoin and the development of IBD, though such observations may have resulted from chance, confounding, bias, and misrepresentation of the natural history of IBD. A causal relationship remains biologically plausible, but beneficial effects of vitamin A derivatives on intestinal injury have been reported as well. None of the other commonly accepted causal criteria are met. The lack of evidence does not necessarily indicate lack of a causal connection. However, in the absence of observational studies which assess the strength and consistency of the association and/or experimental studies which confirm such an association, any conclusions about a causal link are premature at best, and future studies are needed to enable a more rigorous assessment about causality. Until such time as that becomes possible, it is difficult to provide any substantive assessment of the IBD-associated risks of isotretinoin use. Therefore, while it remains possible that an association between isotretinoin and IBD will eventually be established, current published evidence is insufficient to support this claim.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: Dr. Crockett was supported, in part, by a grant from the National Institutes of Health: T32 DK 07634. Dr. Kappelman was supported in part by the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) Grant KL2 RR025746.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest/study support:

Potential competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Ahmed R, Pezzone M. Isoretinoin-associated ulcerative colitis. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2006;101:S394. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bankar RN, Dafe CO, Kohnke A, et al. Ulcerative colitis probably associated with isotretinoin. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2006;25:171–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borobio E, Arin A, Valcayo A, et al. Isotretinoin and ulcerous colitis. An Sist Sanit Navar. 2004;27:241–3. doi: 10.4321/s1137-66272004000300009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mennecier D, Poyet R, Thiolet C, et al. Ulcerative colitis probably induced by isotretinoin. Gastroenterologie Clinique Et Biologique. 2005;29:1306–1307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reniers DE, Howard JM. Isotretinoin-induced inflammatory bowel disease in an adolescent. Ann Pharmacother. 2001;35:1214–6. doi: 10.1345/aph.10368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rolanda C, Macedo G. Isotretinoin and inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1330. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Accutane package insert. 2009 March 1; [cited. Available from: http://www.rocheusa.com/products/accutane/pi.pdf.

- 8.Reddy D, Siegel CA, Sands BE, et al. Possible association between isotretinoin and inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1569–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill AB. The Environment and Disease: Association or Causation? Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:295–300. doi: 10.1177/003591576505800503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brodin MB. Inflammatory bowel disease and isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:843. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(86)80535-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deplaix P, Barthelemy C, Vedrines P, et al. Probable acute hemorrhagic colitis caused by isotretinoin with a test of repeated administration. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1996;20:113–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin P, Manley PN, Depew WT, et al. Isotretinoin-associated proctosigmoiditis. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:606–9. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90925-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Melki M, Pouderoux P, Pignodel C, et al. Granulomatous colitis likely induced by isotretinoin. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2001;25:433–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moneret-Vautrin DA, Delvaux M, Labouyrie E, et al. Collagenous colitis: possible link with isotretinoin. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;38:124–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spada C, Riccioni ME, Marchese M, et al. Isotretinoin-associated pan-enteritis. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2008;42:923–925. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318033df5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Passier JL, Srivastava N, van Puijenbroek EP. Isotretinoin-induced inflammatory bowel disease. Neth J Med. 2006;64:52–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loftus EV, Jr., Silverstein MD, Sandborn WJ, et al. Crohn’s disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940-1993: incidence, prevalence, and survival. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1161–8. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70421-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stonnington CM, Phillips SF, Melton LJ, 3rd, et al. Chronic ulcerative colitis: incidence and prevalence in a community. Gut. 1987;28:402–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.28.4.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wysowski DK, Swann J, Vega A. Use of isotretinoin (Accutane) in the United States: rapid increase from 1992 through 2000. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:505–9. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.120529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anonymous US Census Population Clock. 2009 February 6; cited. Available from: http://www.census.gov/population/www/popclockus.html.

- 21.Brewer T, Colditz GA. Postmarketing surveillance and adverse drug reactions: current perspectives and future needs. JAMA. 1999;281:824–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.9.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guslandi M. Isotretinoin and inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1546–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruno NP, Beacham BE, Burnett JW. Adverse effects of isotretinoin therapy. Cutis. 1984;33:484–6. 489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dessoukey MW, Omar MF, Dayem HA. Pyoderma faciale: manifestation of inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:724–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1996.tb00647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ali M, Duerksen DR. Ulcerative colitis and Sweet’s syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22:296–8. doi: 10.1155/2008/960585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Osanai M, Nishikiori N, Murata M, et al. Cellular retinoic acid bioavailability determines epithelial integrity: Role of retinoic acid receptor alpha agonists in colitis. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:250–8. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.029579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mucida D, Park Y, Kim G, et al. Reciprocal TH17 and regulatory T cell differentiation mediated by retinoic acid. Science. 2007;317:256–60. doi: 10.1126/science.1145697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mora JR, von Andrian UH. Role of retinoic acid in the imprinting of gut-homing IgA-secreting cells. Semin Immunol. 2009;21:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guruvayoorappan C, Kuttan G. 13 cis-retinoic acid regulates cytokine production and inhibits angiogenesis by disrupting endothelial cell migration and tube formation. J Exp Ther Oncol. 2008;7:173–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosen T, Unkefer RP. Treatment of pyoderma faciale with isotretinoin in a patient with ulcerative colitis. Cutis. 1999;64:107–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Godfrey KM, James MP. Treatment of severe acne with isotretinoin in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Br J Dermatol. 1990;123:653–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1990.tb01483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McHenry PM, Hudson M, Smart LM, et al. Pyoderma faciale in a patient with Crohn’s disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:460–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1992.tb00262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schleicher SM. Oral isotretinoin and inflammatory bowel disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:834–5. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(85)80411-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsianos EV, Dalekos GN, Tzermias C, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa in Crohn’s disease. A further support to this association. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;20:151–3. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199503000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Macdonald Hull SCW. The Safety of Isotretinoin in Patients With Acne and Systemic Diseases. J Derm Treat. 1989;1:35–37. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K, et al. The prevalence and geographic distribution of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1424–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peck GL, Olsen TG, Butkus D, et al. Isotretinoin versus placebo in the treatment of cystic acne. A randomized double-blind study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;6:735–45. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(82)70063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lammer EJ, Chen DT, Hoar RM, et al. Retinoic acid embryopathy. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:837–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198510033131401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fender AB, Ignatovich Y, Mercurio MG. Pyoderma faciale. Cutis. 2008;81:488–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]