Abstract

Colonic necrosis is known as a rare complication following the administration of Kayexalate (sodium polystryrene sulfonate) in sorbitol. We report a rare case of colonic mucosal necrosis following Kalimate (calcium polystryrene sulfonate), an analogue of Kayexalate without sorbitol in a 34-yr-old man. He had a history of hypertension and uremia. During the management of intracranial hemorrhage, hyperkalemia developed. Kalimate was administered orally and as an enema suspended in 20% dextrose water to treat hyperkalemia. Two days after administration of Kalimate enema, he had profuse hematochezia, and a sigmoidoscopy showed diffuse colonic mucosal necrosis in the rectum and sigmoid colon. Microscopic examination of random colonic biopsies by two consecutive sigmoidoscopies revealed angulated crystals with a characteristic crystalline mosaic pattern on the ulcerated mucosa, which were consistent with Kayexalate crystals. Hematochezia subsided with conservative treatment after a discontinuance of Kalimate administration.

Keywords: Polystyrene Sulfonic Acid, Colon, Necrosis

INTRODUCTION

Kayexalate (sodium polystryrene sulfonate, SPS) is a cation-exchange resin often administered orally or as an enema with sorbitol to treat hyperkalemia. Colonic necrosis has been described as a rare complication after administration of kayexalate in the literature (1-5). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first histologically proven case in Korea of colonic mucosal necrosis following Kalimate (calcium polystryrene sulfonate), an analogue of Kayexalate. In contrast to previously reported cases, this patient was treated with Kalimate suspended in 20% dextrose water (DW), not in sorbitol that has been known to have a toxic effect on the mucosa rather than Kayexalate itself (1). However this patient revealed the same clinical manifestation and pathologic changes as patients who showed colonic necrosis after treatment of Kayexalate in sorbitol.

CASE REPORT

34-yr-old man was admitted to the hospital because of a sudden development of headache, sweating and vomiting. He had a history of hypertension and chronic renal failure due to IgA nephropathy. After 3 yr of peritoneal dialysis (one and a half years before the current admission), hemodialysis was initiated. At the time of the patient's visit to the emergency room, his temperature was 37℃, the pulse was 95 beats per minute, the respiratory rate was 25 breaths per minute and the blood pressure was 162/86 mmHg. Brain computed tomography (CT) revealed intracerebral hemorrhage in the left thalamus and intraventricular hemorrhages in both lateral ventricles, and the third and fourth ventricles. Burr hole operation with external ventricular drainage (EVD) was performed. Laboratory test performed on the admission day showed uremia, creatinemia and hyperkalemia. Intermittent hemodialysis was done and Kalimate (Kunwha Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Korea, 10 g, b.i.d.) was administered orally. On the ninth day of admission, the level of potassium was highly elevated (8.0 mEq/L) and an electrocardiogram showed ST-segment depressions and poor R wave progression. For the management of hyperkalemia, two enemas with Kalimate preparation (30 g of Kalimate in 200 mL of 20% DW each) were performed, and oral Kalimate (15 g, t.i.d.) had been given for three days. Two days later, profuse hematochezia developed. A sigmoidoscopy was performed, revealing diffuse active ulceration with mucosal necrosis and hemorrhage from the rectum to beyond the reach of an endoscope (Fig. 1). Multifocal pseudomembrane formations were found. Random biopsies from multiple ulcerative areas were performed.

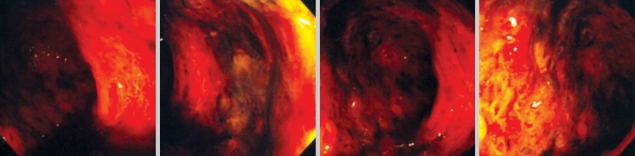

Fig. 1.

A sigmoidoscopy shows diffuse ulceration with pseudomembrane formation in the entire sigmoid colon and rectum.

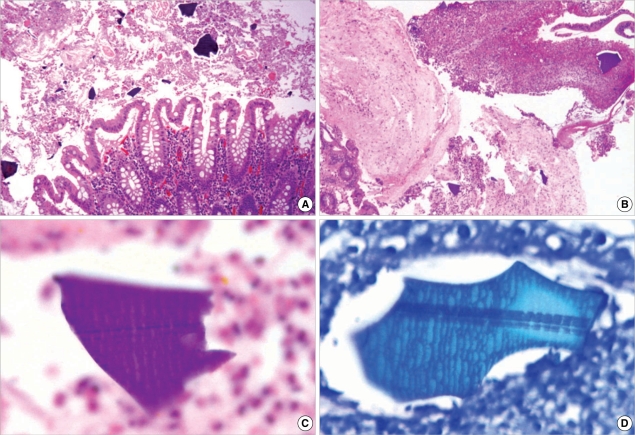

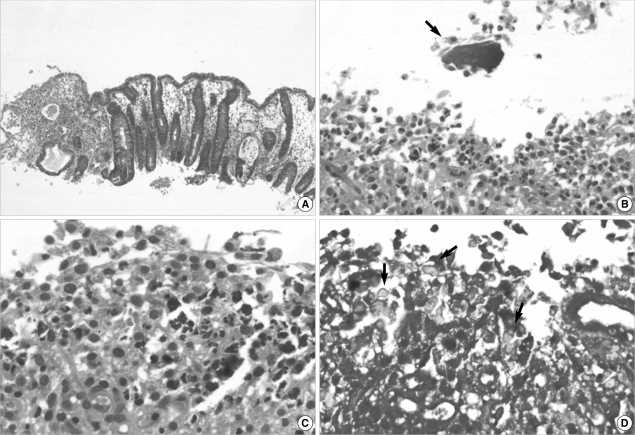

Histologically, the colonic mucosa showed active colitis with mucosal necrosis or ulceration. There were irregular shaped and sized, angulated crystals with a characteristic crystalline mosaic pattern on the mucosa and ulcer bed tissue and within the necroinflammatory debris (Fig. 2A, B). They were basophilic on H&E stain (Fig. 2C), blue on Diff-Quik stain (Fig. 2D) features of viral infection or acute ischemic colitis, such as withering crypts, stromal hyalinization or fibrin thrombi in the vessels. Also there were no features of chronic colitis, including inflammatory bowel disease, chronic diverticular disease-associated colitis or chronic ischemic colitis. After the discontinuance of Kalimate, conservative treatment was initiated. One week after the initial sigmoidoscopy, a follow-up sigmoidoscopy was performed, showing multiple scattered ulcers with slight improvement. Random biopsies were obtained from the different levels of the rectum, sigmoid and lower descending colon, showing healing ulcerations with the presence of a few remaining crystals (Fig. 3). Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) toxin assays had been performed four times during the period between endoscopic examinations and 2 weeks after the second endoscopy, and all were negative. Hematochezia gradually subsided and disappeared, however the patient died of cardiovascular problems on the forty fifth day of admission.

Fig. 2.

Microphotographs of Kalimate crystals. (A, B) Angulated crystals are seen on the colonic mucosa and admixed within necroinflammatory exudates (H&E stain, ×100 and ×40). The crystals are basophilic on H&E stain (C, ×1,000) and blue on Diff-Quik stain (D, ×1,000). A characteristic crystalline mosaic pattern is better demonstrated with Diff-Quick staining (D).

Fig. 3.

Microphotographs of the follow up colonic biopsy. (A) Colonic mucosa shows crypt regeneration and granulation tissue formation (H&E stain, ×40). (B) The remaining Kalimate crystal (arrow) shows a degenerative appearance with an irregular edge and surrounding inflammatory activity (H&E stain, ×200). (C) Small fragments of crystal are embedded in the inflamed granulation tissue (H&E stain, ×400), crystalloid appearances (arrows) of which are highlighted on Diff-Quick stain (D, ×400)

DISCUSSION

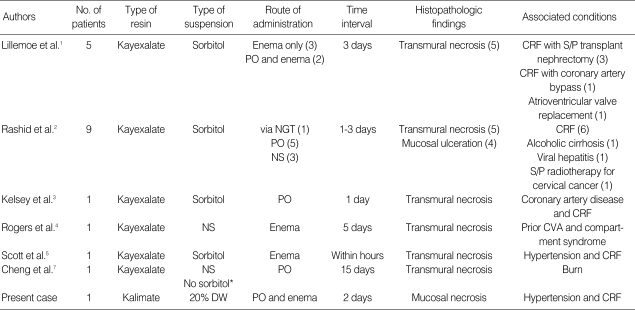

Kayexalate (sodium polystryrene sulfonate) is a cation-exchange resin that has been widely used for the management of hyperkalemia since the 1970s. It can be administered orally or by nasogastric tube or instilled into the colon as an enema preparation. Kayexalate was mixed with sorbitol, a hypertonic solution to avoid constipation, fecal impaction or Kayexalate bezoar formation (6). Lillemoe et al. reported the first series of five patients with uremia who had colonic necrosis that was associated with the use of Kayexalate enema suspended in sorbitol in 1987 (1). Its occurrence was reported in approximately 1% of patients receiving Kayexalate in sorbitol (2), most of whom had multiple medical and/or surgical problems, especially including uremia (1-7). Clinicopathologic findings of patients with Kayexalate-associated colonic necrosis in the literature are summarized in Table 1. Most cases of colonic necrosis after administration of Kayexalate are diagnosed in one to several days after the last dose is given (3). Kayexalate-associated mucosal necrosis is more common in the lower gastrointestinal (GI) tract, however occurrences in the upper GI tract, including the esophagus, stomach and duodenum were also reported (2, 6). The clinical course of colonic necrosis was sometimes fatal, while patients with upper GI lesions rarely required surgical resection and usually recovered (6).

Table 1.

Summary of clinicopathologic findings of patients with Kayexalate-associated colonic necrosis in the literature and the present case

*They didn't specify the type of suspension for Kayexalate administration, but mentioned that Kayexalate was administered without sorbitol. The number in parenthesis indicates the number of patients.

No., number; NS, not specified; DW, dextrose water; NGT, nasogastric tube; PO, per oral; CRF, chronic renal failure; S/P, status post; CVA, cardiovascular accident.

Kalimate is a calcium-type resin that has the same pharmacological action as Kayexalate. Unlike Kayexalate (sodium-typed resin), Kalimate does not cause an increase in serum sodium and phosphate levels or a decrease in serum calcium level, so it is used even for sodium-restricted patients. The mechanism of Kayexalate in the development of colonic necrosis remains unclear. However, according to the results of experimental studies, administration of Kayexalate alone without sorbitol was not found to cause any significant pathological changes (1). Therefore, sorbitol is believed to an agent that has a toxic effect on the gastrointestinal mucosa, possibly through increasing prostaglandin activity. On the other hand, Cheng et al. (7) reported that a patient being given Kayexalate without sorbitol showed the same pathologic features. According to the manufacturer's guideline for Kalimate, a single dose of 30 g is suspended in 100 mL of water or a 2% methylcellulose solution or 5% DW. Twenty percent DW, a hypertonic solution, has been also commonly used as a suspension solution to enhance the enema effect as in this case. It is uncertain whether the use of 20% DW as a mixing solution may play a part in the development of mucosal necrosis. Thus, further investigation of the role of Kayexalate itself or different types of suspension in the development of mucosal necrosis seems to be necessary.

Gastrointestinal complications in the patients who have multiple medical or surgical problems, such as uremia, immunosuppression or transplantation are not uncommon. Ischemic colitis, opportunistic infection and antibiotic-induced C. difficile colitis are the main differential diagnoses for patients with bloody diarrhea (8, 9). Endoscopic findings characterized by pseudomembrane formation, mucosal ulceration, edema or hemorrhage as seen in this case are insufficient to differentiate ischemic colitis, pseudomembranous colitis, infectious colitis, such as Escherichia coli O157:H7 or Kayexalate-associated mucosal necrosis. Also there can be considerable histologic overlapping. Therefore, it is difficult to define the etiology for colonic necrosis in the patients who present with multiple medical problems and are susceptible to mucosal injury. Combined clinical, laboratory and histologic examinations are mandatory to exclude the common causes of mucosal necrosis as well as to make a diagnosis of Kayexalate-associated mucosal necrosis. However foremost, the observation of angulated crystals of Kayexalate with a characteristic crystalline mosaic pattern is crucial to diagnose Kayexalate-associated mucosal necrosis (2, 6). From a histological aspect, crystals of cholestyramine (used to lower high levels of cholesterol in the blood or to treat the itching that is associated with a blockage of the biliary tract) have to be differentiated from Kayexalate crystals: the former is more basophilic, opaque without a mosaic pattern and rhomboid in shape compared to the latter (2). The microscopic appearances of Kalimate crystals were the same as the well-known features of Kayexalate crystals.

In this patient, no evidence of systemic infection, negative C. difficile toxin assays, no histologic features suggestive of viral infections or ischemic colitis and the presence of extensive mucosal necrosis with Kayexalate crystals help to make a diagnosis. We think it is necessary for the clinician to be aware of that the use of Kayexalate (or Kalimate) preparation can be related to gastrointestinal, especially colonic mucosal necrosis in a small subset of patients who have multiple medical problems. Recognition of Kayexalate crystals is important for pathologists in reaching a correct diagnosis.

References

- 1.Lillemoe KD, Romolo JL, Hamilton SR, Pennington LR, Burdick JF, Williams GM. Intestinal necrosis due to sodium polystyrene (Kayexalate) in sorbitol enemas: clinical and experimental support for the hypothesis. Surgery. 1987;101:267–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rashid A, Hamilton S. Necrosis of the gastrointestinal tract in uremic patients as a result of sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate) in sorbitol: an underrecognized condition. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:60–69. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199701000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelsey PB, Chen S, Lauwers GY. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 37-2003. A 79-year-old man with coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, end-stage renal disease, and abdominal pain and distention. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2147–2155. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcpc030031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rogers FB, Li SC. Acute colonic necrosis associated with Sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate) enemas in a critically ill patient: Case report and review of literature. J Trauma. 2001;51:395–397. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200108000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott TR, Graham SM, Schweitzer EJ, Bartlett ST. Colonic necrosis following sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate)-sorbitol enema in a renal transplant patient. Report of a case and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:607–609. doi: 10.1007/BF02049870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abraham SC, Bhagavan BS, Lee LA, Rashid A, Wu TT. Upper gastrointestinal tract injury in patients receiving kayexalate (sodium polystyrene sulfonate) in sorbitol: clinical, endoscopic, and histopathologic findings. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:637–644. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200105000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng ES, Stringer KM, Pegg SP. Colonic necrosis and perforation following oral sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Resonium A/Kayexalate) in a burn patient. Burns. 2002;28:189–190. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(01)00099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ponticelli C, Passerini P. Gastrointestinal complications in renal transplant recipients. Transpl Int. 2005;18:643–650. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2005.00134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Komorowski RA, Cohen EB, Kauffman HM, Adams MB. Gastrointestinal complications in renal transplant recipients. Am J Clin Pathol. 1986;86:161–167. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/86.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]