Abstract

We performed a transmission study using mice to clarify the characteristics of the most recent case of scrapie in Japan. The mice that were inoculated with the brain homogenate from a scrapie-affected sheep developed progressive neurological disease, and one of the scrapie-affected mice showed unique clinical signs during primary transmission. This mouse developed obesity, polydipsia, and polyuria. In contrast, the other affected mice exhibited weight loss and hypokinesia. In subsequent passages, the mice showed distinct characteristic scrapie phenotypes. This finding may prove that different prion strains coexist in a naturally affected sheep with scrapie.

Scrapie is a transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE) that affects sheep and goats. It is characterized by spongiform changes in the central nervous system (CNS) and accumulation of an abnormal prion protein (PrPSc) in the CNS and lymphoid tissues; PrPSc is the major component of prions [1]. Thus far, multiple strains of scrapie prions have been identified [2–6]. These strains can be distinguished on the basis of the incubation period, the lesion profile, and the pattern of the PrPSc accumulation in the transmission studies with mice. The characteristic phenotypes of these prion strains are conserved during serial passage within a single host [2]. However, the mechanism of emergence of prion strains is still unknown.

A 60-month-old Suffolk ewe developed ananastasia and eventually died in Kanagawa prefecture, Japan, and it was diagnosed as scrapie (Ka/scrapie). To clarify the biological properties of prions in this most recent case of scrapie in Japan, we examined the transmissibility of scrapie prions in wild-type ICR mice (PrP allotype PrPA/A; PrPA encodes PrP with leucine at codon 108 and threonine at codon 189; Japan SLC, Inc., Japan) by using previously described methods [7]. All of the mice that were inoculated with the brain homogenate of scrapie-affected sheep developed progressive neurological diseases; one of the disease-affected mice exhibited unique clinical signs during primary transmission (Table 1). After an incubation period of 469 days, this mouse developed obesity, polydipsia, and polyuria followed by slowness of movement; the prion responsible for these symptoms is designated as the Ka/scrapie obesity-type (Ka/O) prion. In contrast, after an incubation period of 457 ± 21.1 days, the other disease-affected mice (15) exhibited weight loss, hypokinesia, and uncoordinated hind-limb movements; the prion responsible for these symptoms was designated as the Ka/scrapie weight-loss-type (Ka/W) prion. To further investigate the properties of these prions, brain homogenates from the Ka/O- and Ka/W-affected mice were inoculated into wild-type mice, and these mice were subjected to neuropathological and biochemical examinations. The mice that were inoculated with the brain homogenate of the Ka/O-affected mouse developed obesity, polydipsia, and polyuria after an incubation period of 287.0 ± 6.5 days. Conversely, those inoculated with the brain homogenate of the Ka/W-affected mice exhibited weight loss and hind-limb ataxia after an incubation period of 255.8 ± 28.2 days. Moreover, mice in the subsequent Ka/O and Ka/W passage lines showed different clinical signs, and the incubation periods of the third passage lines in the Ka/O- and Ka/W-affected mice were 272.3 ± 29.0 and 151 ± 5.6 days, respectively. The body weights of the Ka/O- and Ka/W-affected mice at the third passage are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Transmission of Ka/scrapie in wild-type ICR mice

| First passage (16/16a) | Second passage | Third passage | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15/16b | 457 ± 21.1c | → | 5/5 | 255.8 ± 28.8 | → | 10/10 | 151.5 ± 5.6 |

| 1/16d | 469 | → | 5/5 | 287.0 ± 6.5 | → | 10/10 | 272.3 ± 29.0 |

aNumber of infected mice/number of inoculated mice

bMice exhibiting weight loss and hind-limb ataxia. All of these mice showed the same clinical signs and same neuropathological phenotype. The brain homogenate of 1 of the 15 mice was used for the second passage (incubation period, 463 days)

cAverage ± standard deviation (days)

dA single mouse exhibiting polydipsia, polyuria, and obesity

Table 2.

Body weights of the Ka/W- and Ka/O-affected wild-type ICR mice

| Inoculuma | Mouse numbers | Weeks post-inoculation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 12 | 20 | 28 | 32 | 36 | ||

| Ka/W | 6 | 12.3 ± 1.0b | 39.5 ± 7.8 | 36.2 ± 6.9* | |||

| Ka/O | 6 | 12.5 ± 0.9 | 44.1 ± 3.8 | 56.8 ± 5.5* | 68.8 ± 3.7** | 68.6 ± 7.5* | 61.4 ± 9.4 |

| Control | 6 | 12.6 ± 0.7 | 40.1 ± 6.4 | 47.5 ± 9.0 | 49.0 ± 9.0 | 46.2 ± 6.9 | 47.8 ± 8.9 |

The asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between the scrapie-affected mice and the age-matched control mice (Student’s t test: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.001)

aKa/scrapie weight-loss-type prion (Ka/W)- and Ka/scrapie obesity-type prion (Ka/O)-affected ICR mice at third passage were analyzed

bAverage ± standard deviation (gram)

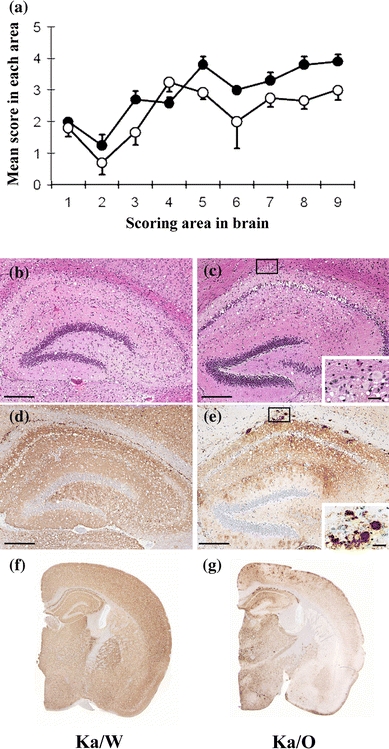

Neuropathological examinations of these mice were performed by using previously described methods [7]. Spongiform changes were detected throughout the brains of both the Ka/W- and Ka/O-affected mice. The degree of vacuolation in the brains of the Ka/W-affected mice was more severe than that in the Ka/O-affected mice (Fig. 1a–c). Immunohistochemical analyses were performed by using previously described methods [7, 8]. The PrPSc types and their distributions in the Ka/O- and Ka/W-affected mice were different (Fig. 1d–g). Punctate and fine granular PrPSc were predominantly and uniformly distributed throughout the brains of the Ka/W-affected mice (Fig. 1d, f). In contrast, in the Ka/O-affected mice, coarse granular PrPSc was predominantly distributed in the thalamus, the brain stem, and the cerebral cortex (Fig. 1e, g), while PrP plaques were observed in the corpus callosum, the thalamus, and the cerebral cortex (inset of Fig. 1e).

Fig. 1.

Neuropathological analysis of the Ka/scrapie weight-loss-type prion (Ka/W)- and Ka/scrapie obesity-type prion (Ka/O)-affected mice. a Lesion profile of the affected mice. The vacuolation in the following brain regions was scored on a scale of 0–5 (mean values): 1 dorsal medulla, 2 cerebellar cortex, 3 superior cortex, 4 hypothalamus, 5 thalamus, 6 hippocampus, 7 septal nuclei of the paraterminal body, 8 cerebral cortex at the levels of the hypothalamus and the thalamus, and 9 cerebral cortex at the level of the septal nuclei of the paraterminal body [18]. Filled circle Ka/W (n = 5), open circle Ka/O (n = 5). A section of the hippocampus of the affected mice was stained with hematoxylin and eosin (b, c), and immunostaining was performed by using the monoclonal antibody (mAb) SAF84 (d–g). The coronal sections at the level of the hippocampus are shown (f, g). The insets in the lower right corners (c, e) are enlarged images of the small boxes in the corresponding panels. The bar represents 200 µm in b–d and 25 µm in the insets of c and e

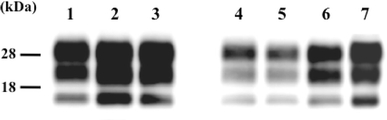

In recent studies, prion strains have been distinguished on the basis of the biochemical properties of the PrPSc, such as the glycoform ratio and the molecular mass of proteinase-K-digested PrPSc (PrPcore) [9–13]. We characterized the PrPcore molecules that had been extracted from the brains of the Ka/O- and Ka/W-affected mice by using a previously described method [14]. Western blotting (WB) analysis revealed that the PrPcore obtained from the Ka/O- and Ka/W-affected mice had similar glycoform patterns and molecular mass (Fig. 2). These results indicate that two strains of prions with distinct properties were isolated from a single source, i.e., the brain of the scrapie-affected sheep.

Fig. 2.

Western blotting (WB) analysis for detecting proteinase-K-digested prion protein (PrPcore) in the brains of Ka/scrapie weight-loss-type prion (Ka/W)- and Ka/scrapie obesity-type prion (Ka/O)-affected mice. Lanes 1–3 Ka/W-affected mice, lanes 4–6 Ka/O-affected mice, lane 7 Ka/scrapie. Lanes 1 and 4: mice in the first passage; lanes 2 and 5: mice in the second passage; and lanes 3 and 6: mice in the third passage. The equivalent of 0.25 µg of brain tissue was loaded into each lane. PrPcore was detected using the monoclonal antibody (mAb) T2 [19]. The molecular markers are shown on the left (kDa)

Different types of PrPSc (types 1 and 2) were reported to co-exist in a case of sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jacob disease (sCJD) [15]. Scrapie in sheep is also proposed to be caused by mixed populations of different prion strains [16, 17]. In the present study, different prion strains were isolated from the brain of a scrapie-affected sheep during the primary transmission studies. In the previously reported CJD case, the PrPcore sizes of the two strains were different. In contrast, in the case reported in this study, although their PrPcore sizes were not different, the prions of the two strains showed distinct biological characteristics. In addition, this result showed that a transmission study using experimental animals is a useful approach for the isolation and characterization of prion strains. New TSE strains are believed to emerge due to mutations caused by differences in the primary PrP sequences of the host and the inoculum [17]. We observed that 3 out of 31 mice showed the characteristic clinical signs of the Ka/O strain in repeat trials of Ka/scrapie transmission (data not shown). This data indicates that the Ka/O strain shows a constant occurrence rate of 6–9%. Therefore, our findings may indicate that mixed prion populations exist in a scrapie-affected sheep and that one of these strains becomes dominant during prion propagation in mice. Our results suggested that the Ka/W strain was the dominant strain in the brain of Ka/scrapie-affected sheep, while the Ka/O strain seemed to be the less dominant strain, which may have been inefficiently selected during interspecies transmission.

In this study, we examined the biological characteristics of prions in the most recent case of scrapie in Japan. On the basis of our results, we conclude that multiple prion strains coexist in a scrapie-affected sheep. To elucidate the molecular epidemiology of prion diseases, further studies should be conducted to clarify the mechanism underlying the emergence of new prion strains.

Acknowledgments

All animal experiments were reviewed by the Committee of the Ethics on Animal Experiment of the National Institute of Animal Health. We are thankful to Naoko Tabeta and Mutsumi Sakurai for their technical assistance. This study was supported by a grant-in-aid from the BSE and other Prion Disease Control Project of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries, Japan.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Abbreviations

- PrPSc

Abnormal prion protein

- CNS

Central nervous system

- Ka/O

Kanagawa/scrapie obesity-type prion

- Ka/W

Kanagawa/scrapie weight-loss-type prion

- mAb

Monoclonal antibody

- PrP

Prion protein

- PrPcore

Proteinase-K-digested PrPSc

- sCJD

Sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jacob disease

- TSE

Transmissible spongiform encephalopathy

- WB

Western blotting

Footnotes

K. Masujin and Y. Shu contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Prusiner SB. Molecular biology of prion diseases. Science. 1991;252:1515–1522. doi: 10.1126/science.1675487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kimberlin RH, Walker CA, Fraser H. The genomic identity of different strains of mouse scrapie is expressed in hamsters and preserved on reisolation in mice. J Gen Virol. 1989;70:2017–2025. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-8-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruce ME. Scrapie strain variation and mutation. Br Med Bull. 1993;49:822–838. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shinagawa M, Takahashi K, Sasaki S, Doi S, Goto H, Sato G. Characterization of scrapie agent isolated from sheep in Japan. Microbiol Immunol. 1985;29:543–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1985.tb00856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horiuchi M, Nemoto T, Ishiguro N, Furuoka H, Mohri S, Shinagawa M. Biological and biochemical characterization of sheep scrapie in Japan. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:3421–3426. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.9.3421-3426.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirogari Y, Kubo M, Kimura KM, Haritani M, Yokoyama T. Two different scrapie prions isolated in Japanese sheep flocks. Microbiol Immunol. 2003;47:871–876. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2003.tb03453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masujin K, Shu Y, Yamakawa Y, Hagiwara K, Sata T, Matsuura Y, Iwamaru Y, Imamura M, Okada H, Mohri S, Yokoyama T. Biological and biochemical characterization of L-type-like bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) detected in Japanese black beef cattle. Prion. 2008;2:123–128. doi: 10.4161/pri.2.3.7437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furuoka H, Yabuzoe A, Horiuchi M, Tagawa Y, Yokoyama T, Yamakawa Y, Shinagawa M, Sata T. Species-specificity of a panel of prion protein antibodies for the immunohistochemical study of animal and human prion diseases. J Comp Pathol. 2007;136:7–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bessen RA, Marsh RF. Biochemical and physical properties of the prion protein from two strains of the transmissible mink encephalopathy agent. J Virol. 1992;66:2096–2101. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.2096-2101.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collinge J, Sidle KC, Meads J, Ironside J, Hill AF. Molecular analysis of prion strain variation and the aetiology of ‘new variant’ CJD. Nature. 1996;383:685–690. doi: 10.1038/383685a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parchi P, Capellari S, Chen SG, Petersen RB, Gambetti P, Kopp N, Brown P, Kitamoto T, Tateishi J, Giese A, Kretzschmar H. Typing prion isoforms. Nature. 1997;386:232–234. doi: 10.1038/386232a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Somerville RA, Chong A, Mulqueen OU, Birkett CR, Wood SC, Hope J. Biochemical typing of scrapie strains. Nature. 1997;386:564. doi: 10.1038/386564a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuczius T, Groschup MH. Differences in proteinase K resistance and neuronal deposition of abnormal prion proteins characterize bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) and scrapie strains. Mol Med. 1999;5:406–418. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yokoyama T, Kimura KM, Ushiki Y, Yamada S, Morooka A, Nakashiba T, Sassa T, Itohara S. In vivo conversion of cellular prion protein to pathogenic isoforms, as monitored by conformation-specific antibodies. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:11265–11271. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008734200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Puoti G, Giaccone G, Rossi G, Canciani B, Bugiani O, Tagliavini F. Sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jacob disease: co-occurrence of different types of PrPSc in the same brain. Neurology. 1999;53:2173–2176. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.9.2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kimberlin RH, Walker CA. Evidence that the transmission of one source of scrapie agent to hamsters involves separation of agent strains from a mixture. J Gen Virol. 1978;39:487–496. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-39-3-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collinge J, Clarke AR. A general model of prion strains and their pathogenicity. Science. 2007;318:930–936. doi: 10.1126/science.1138718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fraser H, Dickinson AG. The sequential development of the brain lesion of scrapie in three strains of mice. J Comp Pathol. 1968;78:301–311. doi: 10.1016/0021-9975(68)90006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayashi HK, Yokoyama T, Takata M, Iwamaru Y, Imamura M, Ushiki YK, Shinagawa M. The N-terminal cleavage site of PrPSc from BSE differs from that of PrPSc from scrapie. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;328:1024–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.01.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]