Abstract

The neuronal α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) is one of the most widely expressed nAChR subtypes in the brain. Its subunits have high sequence identity (54% and 46% for α4 and β2, respectively) with α and β subunits in Torpedo nAChR. Using known structure of the Torpedo nAChR as a template, the closed-channel structure of the α4β2 nAChR was constructed through homology modeling. Normal mode analysis was performed on this closed structure and the resulting lowest frequency mode was applied to it for a ‘twist-to-open’ motion, which increased the minimum pore radius from 2.7Å to 3.4Å and generated an open-channel model. Nicotine could bind to the predicted agonist binding sites in the open-channel model, but not in the closed one. Both models were subsequently equilibrated in a ternary lipid mixture via extensive molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Over the course of 11-ns MD simulations, the open channel remained open with filled water, but the closed channel showed a much lower water density at its hydrophobic gate comprising of residues α4-V259, α4-L263 and their homologous residues in β2 subunits. Brownian Dynamics simulations of Na+ permeation through the open channel demonstrated a current-voltage relationship that was in good agreement with experimental data on the conducting state of α4β2 nAChR. Besides establishment of the well-equilibrated closed- and open-channel α4β2 structural models, the MD simulations on these models provided valuable insights into critical factors that potentially modulate channel gating. Rotation and titling of TM2 helices led to changes in orientations of pore-lining residue side-chains. Without concerted movement, the reorientation of one or two hydrophobic side-chains could be enough for channel opening. The closed- and open-channel structures exhibited distinct patterns of electrostatic interactions at the interface of extracellular and transmembrane domains that might regulate the signal propagation of agonist binding to channel opening. A potential prominent role of the β2 subunit in channel gating was also elucidated in the study.

Keywords: nAChR, α4β2, nicotine binding, Channel gating, Cys loop, MD simulation

Introduction

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) belong to the Cys-loop superfamily of ligand gated ion channels that rapidly mediate synaptic signal transduction throughout the nervous system. The abnormal opening and closing of these receptors contribute to severe neurodegenerative diseases.1,2 Members of this superfamily have considerable structural homology. They are pentamers formed either from single or different types of homologous subunits. Each subunit has an extracellular (EC) domain involving a conserved Cys-loop and the ligand binding (LB) site, four transmembrane domains (TM1 through TM4) with TM2 lining the pore of the channel, and an intracellular (IT) segment of variable length.3 The binding of the agonist at the subunit interfaces triggers a concerted conformational change that propagates to the transmembrane domain and opens the channel gate.1 The nAChRs are cation-selective channels and exist as diverse subtypes, including muscle- and neuronal-type. To date nine neuronal α (α2-α10) and three β (β2-β4) subunits have been identified to form functional neuronal-nAChRs, mostly according to a general 2α:3β stoichiometry in heteromeric expression. Among various neuronal-nAChRs, α4β2 is one of the most widely expressed subtypes in the brain. The α4β2 nAChR comprises high-affinity nicotine binding sites4 and shows supersensitive inhibition by volatile anesthetics.5,6 It remains unclear how anesthetics affect the receptor function, primarily due to the lack of structural information on any neuronal nAChRs.

The x-ray crystallographic structures of the acetylcholine binding protein (AChBP, a EC domain homolog of nAChR)7-9 and cryoelectron microscopy structure of the Torpedo nAChR in the resting state3,10 have generated valuable structural insights on nAChRs. The recent success in obtaining the x-ray structure of a prokaryotic pentameric ligand-gated ion channel from the bacterium Erwinia chrysanthemi (ELIT),11 which shares 16% sequence identity to α1 nAChR, has provided another important structural model for understanding the structure-function relationships in nAChRs. However, owing to the lack of structural data for open-channel nAChRs, the mechanism how ligand binding leads to channel opening remains elusive. Several different gating mechanisms have been proposed, including rotation of the pore forming helices,3,10 change of the helix tilt angles with respect to the pore central axis,12-15 and formation of a kink in the middle of the ion-channel.16,17 The location of channel gate(s) that impede ion permeation in nAChR is also controversial. Some studies suggested that hydrophobic girdles close to channel extracellular entrance might serve as the channel gates,18,19 while others implied the gate close to the cytoplasmic face of the channel.20,21 Clearly, a reliable open-channel structure will greatly facilitate the solution of these controversies.

Computational study has emerged as a powerful tool to complement experimental efforts for a comprehensive understanding of protein structures and dynamics. Given that experimental structures are available only for limited number of proteins, homology modeling in conjunction with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and related calculations plays an increasingly important role in structure determination and has proved to be a reliable method for producing high quality models in a wide variety of applications.22-25 It has been elegantly demonstrated26 that one can generate a “ligand-bound” structure from a “ligand-free” structure or vice versa on the basis of low-frequency mode(s) from normal mode analysis (NMA). The resulting structures are in good agreement with the experimentally determined ones. This approach has already been used for generating open-channel models for Torpedo and α7 nAChRs from their closed-channel structures.15,27-29 MD simulation is unique among other computer simulation techniques in providing time-evolved information with atomistic details. Recent successful applications of MD simulations include numerous computational studies of ion channels.17-19,30-32 In order to access ion permeation dynamics at time scales longer than the 10s of nanoseconds which can be computed via all-atom MD, Brownian dynamics (BD) algorithms (in which solvent motion is treated implicitly) have been applied to investigate characteristics of ion permeation in the Torpedo nAChR33 and the glycine receptor,34 demonstrating the utility of this approach for channel conductivity predictions. All these aforementioned methodologies have been utilized in the present study.

For the first time, we have obtained the closed- and putatively open-channel structures of the α4β2 nAChR. The closed structure of the α4β2 nAChR was obtained via homology modeling using the closed-channel Torpedo nAChR (PDB: 2BG9) as a template. The putatively open-channel α4β2 structure was achieved by gradually applying the lowest frequency eigenvectors from normal mode analysis35 to the closed structure. The models thus constructed were subjected to over ten nanoseconds of MD simulations in a fully hydrated and pre-equilibrated ternary lipid patch.36 The quality of these models was evaluated using multiple approaches, including nicotine binding and Na+ permeation through channels. These equilibrated closed- and open-channel models of the α4β2 nAChR have not only provided valuable insights into plausible mechanisms of channel gating, but also a structural basis for further studies involving the α4β2 nAChR, such as investigation of the α4β2 nAChR as a potential target of general anesthetics.

Methods

Homology model of a closed-channel α4β2

The sequences of human nAChR α4 (P43681) and β2 (P17787) were obtained from the ExPASy Molecular Biology Server (http://us.expasy.org).37 To ensure the highest sequence identity to the template and identical structures for same type of subunits, the sequences of α4 and β2 were aligned with the Torpedo Marmorata nAChR α and β sequences (PDB code: 2BG9),3 respectively, using CLUSTALW (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw).38 Sequence alignment between the template and target is shown in the supplementary materials. The 2BG9 structure with repaired missing extracellular residues15 was used as a template for the α4β2 closed-channel homology modeling. For each α4 or β2 subunit, 20 homology models were built and scored by the Discrete Optimized Protein Energy (DOPE) using the Modeller program (version 8.2) (http://salilab.org/modeller).39 The structures with the lowest DOPE values were chosen for building the pentameric model. Two α4- and three β2-subunits were superimposed to the 2BG9 structure using Swiss-PdbViewer40 to generate a pentameric assembly in a counterclockwise configuration of (α4)(β2)(α4)(β2)(β2).41 This method allowed the structures of two α4- and three β2-subunits identical within their own types in the model. The resulting α4β2 model was energy minimized for 10,000 steps with a 500 kcal/mol/Å2 harmonic restraint on its backbone atoms using NAMD 2.6.42 The quality of the model was assessed using the PROCHECK program43 and only 0.6% residues were found in the disallowed regions of the Ramachandran plot.

Normal mode analysis to generate an open-channel conformation

Normal mode analysis (NMA) can effectively delineate the lowest frequency modes that have the greatest contribution to the amplitude of atomic displacement in protein conformational transitions. Elastic-network NMA using a single-parameter Hookean potential44 was performed on the closed-channel α4β2 nAChR through the online elNémo server at http://igs-server.cnrs-mrs.fr/elnemo.35 All heavy atoms of the α4β2 were included in the calculation, in which a default cutoff distance of 8Å45 was applied. The lowest frequency eigenvector was corresponded to a twist-to-open motion, in which a counterclockwise rotation of the EC domains and a clockwise rotation of the TM domains around the pore central axis (Z axis) could be viewed from EC toward TM (Fig. 1). This mode has been suggested previously as a major motional component that regulates channel opening in other nAChRs.15,27-29 The application of the twist-to-open eigenvector with a large amplification to the closed-channel structure could increase the pore radius significantly, but it resulted in a badly deformed protein structure with many broken bonds. Therefore, to achieve a sufficient pore opening but without drastic bond distortion, we generated the open-channel structure through multiple cycles of small displacements of heavy atoms and performed energy minimization on protein in each cycle. The twist-to-open mode was found to be the lowest frequency mode in all cycles of calculations and was used for pore opening using the same formula used previously,15

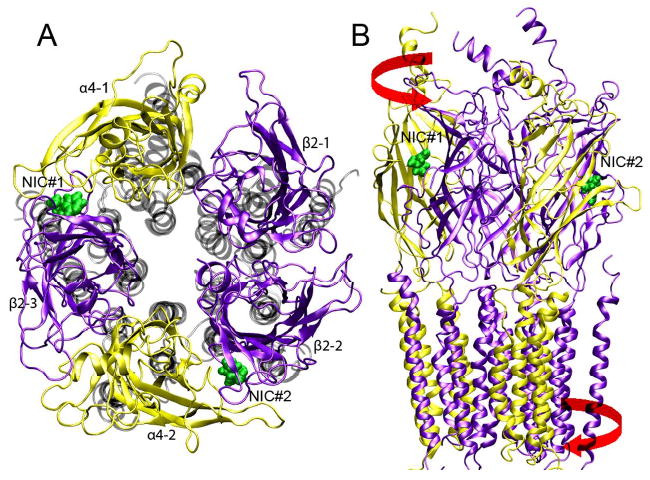

Fig. 1.

Top (A) and side (B) views of an open-channel structure of α4β2 nAChR after 11-ns of MD simulation. The EC domains of α4 and β2 subunits are colored in yellow and violet, respectively. The TM domains in the top view are shown in gray. Two docked nicotine molecules are shown in green. The red arrows in the side view indicate the directions of the “twist-to-open” mode that was applied to the initial closed-channel structure for producing the open-channel.

| [1] |

where R and R0 are the instantaneous and original (or previous cycle) 3N-dimensional vectors (N being the number of residues) of atom coordinates, respectively; λk and μk are the eigenvalue and eigenvector, respectively, of mode k (the twist mode in this study). The “amplification” parameter s varied in the range of 300 to 900 in different cycles. In each cycle, the “amplified” structure underwent 30,000 to 40,000 steps of energy minimizations using the program NAMD.42 The pore radius was evaluated using the Hole program46 at the end of each cycle. After four cycles, the pore size was enlarged significantly such that the minimum pore radius was 3.5Å that was close to the experimentally obtained value of 3.7Å for the open-channel.47 Fig. 1S in the supplementary material shows the pore radius profile after each cycle. The model thus constructed, which had only 0.9% residues in the disallowed regions of the Ramachandran plot, was adopted for further agonist binding and open-channel MD simulations.

System preparation and MD simulations

The transmembrane part of the closed- or open-channel α4β2 structure was inserted into a pre-equilibrated and fully hydrated POPA-POPC-CHOL lipid mixture36 that was experimentally found to be necessary for functional nAChRs.48 Extra TIP3 water molecules were added to fully hydrate the extracellular vestibule of the α4β2 nAChRs. Water molecules were also inserted into the pore of the closed- or open-channel α4β2. Ions were added to neutralize the system and also to obtain a salt concentration of 0.2 M. The resulting closed-channel system had one protein, 162 POPC, 55 POPA, and 55 CHOL lipid molecules, 122 ions (108 Na+ and 14 Cl−) and 33,641 water molecules for a total of 161,202 atoms. The open-channel system had one protein, 160 POPC, 50 POPA, and 54 CHOL lipid molecules; 115 ions (96 Na+ ions and 9 Cl-); 2 nicotine molecules and 28,382 water molecules for a total of 144,540 atoms. Using NAMD 2.6,42 both systems were energy-minimized for 50,000 steps with a harmonic restraint of 500 kcal/mol/Å2 on protein backbones.

MD simulations were preformed using NAMD 2.642 and CHARMM27 force-field parameters49 on BigBen (a Cray XT3 MPP machine) computer at the Pittsburgh Supercomputer Center. The same simulation protocol as reported previously18 was applied to the current systems. The systems, simulated under constant 1 atm pressure and 303 K temperature (NPT ensemble), were regulated via Nosé-Hoover Langevin piston pressure control50,51 and the Langevin damping dynamics.52 Periodic boundary conditions and water wrapping were applied. The bonded interactions and the short-range non-bonded interactions were calculated at every time-step (1 fs) and every two time-steps, respectively. Electrostatic interactions were calculated at every four time-steps using the particle mesh Ewald method.53 The cutoff distance for non-bonded interactions was 12 Å. A smoothing function was employed for the van der Waals interactions at a distance of 10 Å. The pair-list of the nonbonded interaction was calculated every 20 time-steps with a pair-list distance of 13.5Å. An initial harmonic restraint of 250 kcal/mol/Å2 applied to the protein Cα atoms was gradually removed over the course of ∼ 2 ns of MD simulations. A total of 11-ns NPT simulation was performed on each system to fully equilibrate the structure of the closed- or open-channel α4β2 nAChR.

Nicotine docking

The agonist binding to our closed- and open-channel models was evaluated through flexible nicotine docking using the Autodock program (version 3.0.05).54 The nicotine structure was obtained from the x-ray structure of the AChBP-nicotine complex (PDB code 1UW6). 100 independent docking were performed using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm. Because of limited number of allowed grid points in the Autodock program, a grid spacing of 0.436 Å was utilized for each model to cover an entire body of the protein. A smaller grid spacing of 0.375 Å covering whole extracellular domain was also explored to confirm the nicotine docking behind the C-loop. The volume and surface area of the plausible nicotine binding pocket were calculated using CASTp55 with a probe radius of 1.4 Å.

Brownian dynamics simulation of ion permeation

Ion permeation through the equilibrated α4β2 nAChR model channels was studied by performing Brownian dynamics (BD) simulations using a Dynamic Monte Carlo (DMC) algorithm.34,56,57 Detailed description on our BD simulations can be found in supplementary materials. Briefly, protein channel, membrane, and water were treated as continua characterized by different dielectric constants (see Fig.2S in supplementary materials), but ions were treated explicitly undergoing Brownian motion at the effect of electrostatic and dielectric potential. The dielectric constant inside the pore was assumed to be the same as that in the bulk water bath, with εw = 80. The effective dielectric constants for protein and lipids were assumed to be 5 and 2, respectively. Partial charges from CHARMM-27 force field were assigned to protein atoms. The charge on α4-K246 and its homologous β2-K240 (K0′) was set to be neutral as suggested by experiments.14 The membrane was assumed to be neutral in our BD simulations. Radii of 1.8 Å and 0.95 Å were taken for Cl− and Na+, respectively. A diffusion coefficient of D = 2.0×10-5 cm2/s was set for both Na+ and Cl− in bulk water, and assumed to be linearly reduced from this bulk value near the receptor entrances to half of this value near the transmembrane entrances, and maintained this half of the bulk value throughout the whole transmembrane regions.34 We then performed a set of BD simulations for calculating ion permeation. For each specified voltage, a total of 10 individual BD simulations were carried out with each run lasting 5.6 μs.

Data processing and analysis

VMD58 in conjunction with home-developed scripts was used for data analysis and visualization. The radius of gyration about the channel axis (Rg) is defined as

| [2] |

where mi is the mass of Cα atom i, ri = (Xi2+Yi2)1/2 is the distance of the atom i from the central axis of the channel (the z axis), and the sum is over all Cα atoms in the protein. Pore-radius profiles were computed using the HOLE program.46 Water density inside the pore was calculated using a similar method in32 by counting the number of water oxygen atoms inside the simulation box with a bin size of 0.2Å along the z-direction and averaged over the last 3 ns of MD simulations. The helix-tilt-angles were estimated using the method suggested by Cheng et al.59 Previously reported methods for calculation of electrostatic potential60 and dielectric self-energy (DSE)34 were adopted in the current study. Details are provided in the supplementary materials.

Results and Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first time that all-atomic models of the human neuronal α4β2 nAChR at closed- and open-channel states have been generated and equilibrated in tertiary lipid mixtures using MD simulations. We have evaluated the quality of our open-channel structure of the α4β2 nAChR by four criteria: the ability to bind agonist nicotine, the open-pore profile, an adequate water density inside the pore, and resemblance of the open-channel conductance with experimental data. Although our MD simulations were too short to reveal a structural transition from the closed- to open-channel state in the α4β2 nAChR, the simulations were adequate for providing equilibrated structures that allow us to gain insights into plausible channel gating mechanisms and to explore new studies, in which structural information of the α4β2 nAChR is essential. Although wealthy information on protein-lipid interaction from our simulations should be discussed and compared with recent experimental findings,61 we have to focus on only the protein here to keep the manuscript in a reasonable length and will report the protein-lipid interaction elsewhere.

Structural stability and dynamics

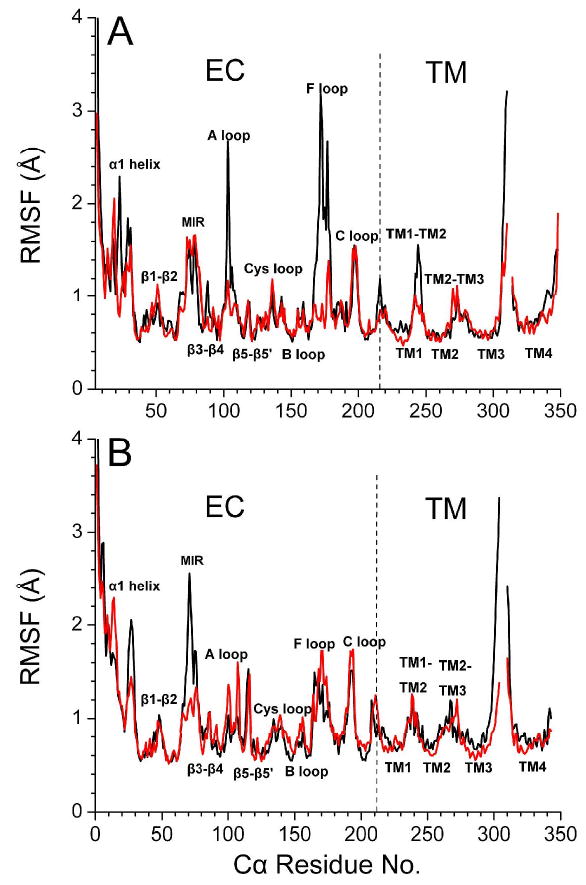

The pentameric structures of both closed and open channels remained reasonably well. Fig. 1 shows the top and side views of the open-channel structure after 11 ns MD simulations. The overall stability of both closed- and open-channel structures was evaluated using the root mean-square deviation (RMSD) of backbone atoms away from their initial homology models. Both model structures stabilized during the last 3-ns simulations (see Fig. 3S in supplementary materials). The flexibility of the models was characterized by the root mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) of the Cα atoms over the last 3-ns simulations. Fig. 2 depicts a comparison of the RMSF in the open- and closed-channel structures, where the RMSF values of the α4 and β2 subunits were averaged separately. Several loops in α4 subunits, including A and F loops and the loop connecting TM2 and TM3 domains, showed significantly higher flexibility in the open-channel structure. In contrast, these loops in β2 subunits demonstrated similar RMSF values in both open- and closed-channel structures or even slightly lower RMSF values in the open-channel structure. However, a much more flexible MIR segment was observed in the open channel model. Overall, the open-channel structure is more flexible than the closed one and the α4 subunit has more highly flexible loops than the β2 subunits.

Fig. 2.

The average Cα RMSF of (A) α4 and (B) β2 subunits from the last 3-ns of MD simulation for the closed- (red) and open-channel (black) structures.

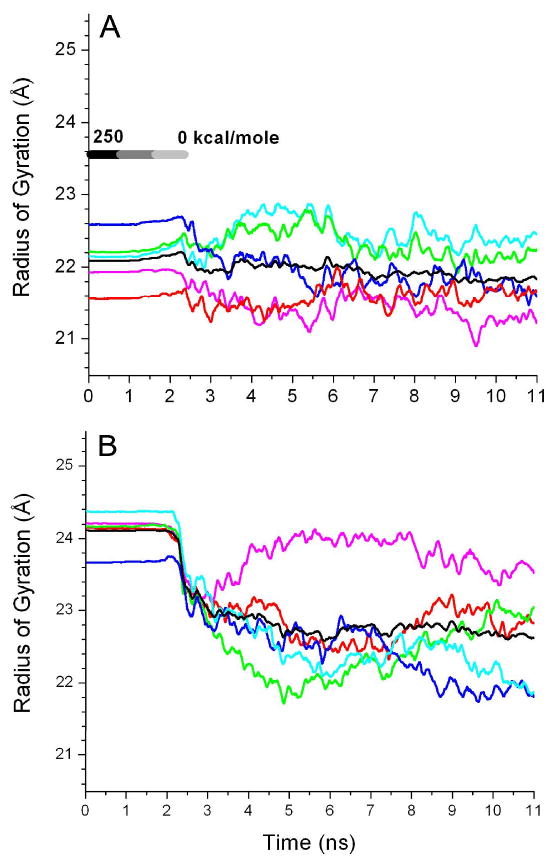

The radius of gyration, Rg, provides a measure of lateral expansion or contraction of each domain relative to the channel axis. We processed Rg separately for the EC and TM domains of individual subunits of the α4β2 nAChR. The Rg values of EC domains in both closed- and open-channel models fluctuated around 27 ± 0.2 Å during the simulations. The lateral expansion or contraction of the TM domains occurred asymmetrically among five subunits in the closed- and open-channel structures over the course of simulations, as shown in Fig. 3. In the closed-channel model, two subunits underwent a small degree of expansion, two underwent contraction, and one remained virtually unchanged. In the open-channel model, four out of five subunits experienced considerable contraction movement after releasing the backbone restraints. Thus, even though the original models were built with a quasi five-fold symmetry, a memory of asymmetric subunit motion over the simulations was saved in the final structures. A certain degree of asymmetry in the channel structures might be an intrinsic property of the protein, as suggested by ample experimental data on asymmetry and subunit nonequivalence during channel gating.62,63

Fig. 3.

Radius of gyration (Rg) of the Cα atoms in the TM domains relative to the central channel axis of (A) the closed channel and (B) the open channel over the course of the MD simulations. The data were smoothed over 100-ps intervals and color coded for individual subunit: α4-1 (magenta), α4-2 (red), β2-1 (green), β2-2 (blue) and β2-3 (cyan). The average Rg of the five subunits is shown in black.

Nicotine binding and its implication

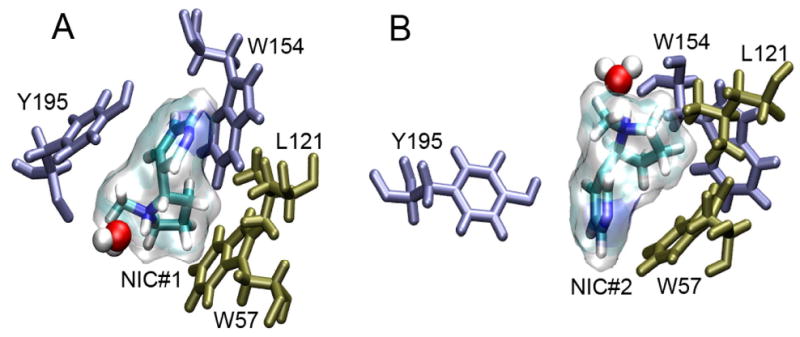

The agonist binding sites were suggested experimentally to be located behind the C-loop of the α subunits.8,64 We attempted docking nicotine to both initial closed- and open-channel structures, which resulted in nicotine binding at the anticipated agonist binding sites only in the open-channel model, but not in the closed-channel model. The distinct difference of agonist binding in our closed- and open-models agrees well with the available experimental evidence.1,65 A close inspection at the C-loops of two α4 subunits and the adjacent F-loops of β2 subunits indicated that the C-loops rotated 2∼5° closer toward the putative nicotine binding pockets in the open-channel structure than those found in the closed one. The average ratio of surface area to volume (SA/V) of the two putative nicotine-binding pockets in the open-channel structure increased 20% in comparison to that in the closed channel. A similar trend of SA/V increasing was also found in the “ligand-bound” (PDB: 1UW6) and “ligand-free” (PDB: 2BYN) structures of ACHBP,8,64 where the average SA/V of agonist binding pockets in the “nicotine-bound” structure (PDB: 1UW6) increased up to 90%. A detailed comparison is provided in the supplementary materials (Table 1S).

It was shown experimentally that agonist binding affinity might differ in two plausible binding sites.66 Nicotine docking in our open-channel structure resulted in different occupancies of the two anticipated binding sites, namely, 31% and 4% in subunits α4–1 and α4–2, respectively. Such a difference might result from small structural differences in the two α-subunits of the original Torpedo nAChR template. Two nicotine molecules, NIC#1 and NIC#2, were selected at respective higher and lower occupancy sites for subsequent MD simulations. In comparison to NIC#2, NIC#1 moved less over the course of an 11-ns MD simulation (see Fig. 4S in the supplementary materials). Fig. 4 depicts potential nicotine interactions with surrounding residues that could stabilize nicotine positions. Better NIC#1 binding might primarily result from the well-aligned stacking of NIC#1 with W154 and Y195 of α4-1 subunit, which could facilitate π-cation interactions.67 The hydrophobic interaction with W57 and L121 of the adjacent β2 subunit also helped to stabilize both nicotine molecules. A high degree of involvement of aromatic residues in the nicotine binding sites agreed well with experimental observation in the nicotine-bound AChBP crystal structure.8 In addition to interactions with the surrounding residues, both nicotine molecules also formed prolonged hydrogen bonds with water in the simulations.

Fig. 4.

(A) NIC#1 in transparent surface appears to be stabilized by π stacking interactions with W154 and Y195 of the α4-1 subunit and hydrophobic interactions with L121 and W57 of the β2-2 subunit. (B) NIC#2 lacks the π stacking interaction of surrounding aromatic residues. Hydrogen bonding with a water molecule is noticeable for both nicotine molecules.

The nicotine binding affected the C-loop flexibility. The RMSF values of the C-loop residues in the open-channel α4-1, where NIC#1 was well bound, were at least 0.5Å smaller than that of corresponding residues in the closed channel. The F-loop of β2 subunit adjacent to nicotine binding sites in the open-channel model also showed smaller RMSF than that in the closed-channel model, presumably due to a closer contact of the β2 F-loop to the putative biding pocket. Therefore, nicotine binding not only affected the flexibility of C-loop, but also rigidified the F-loop in the adjacent β2 subunit. Similar impact of agonist binding to the C-loops or F-loops was also reported and discussed previously.1,15,30,68

Pore-radius profiles, channel water densities, and hydrophobic gate

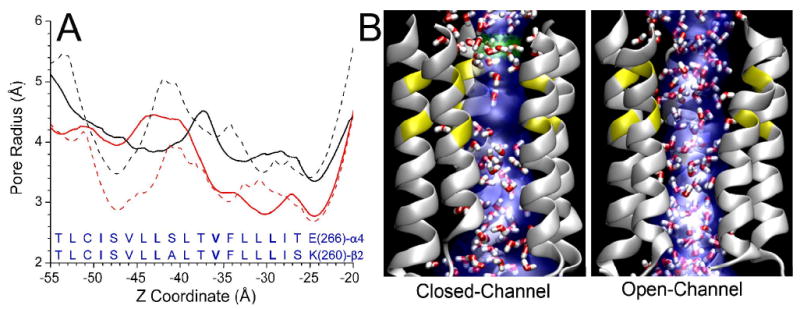

The initial models of the closed and open channels had the minimum pore radii of 2.7Å and 3.4 Å, respectively, at the extracellular channel entrance, where residues α4-E266 and β2-K260 could potentially form salt bridges. After 11-ns simulations, the narrowest pore at the extracellular entrance was essentially unchanged in both models, as shown in Fig. 5A. However, the pore radius near residues α4-L263 and β2-L257 in the closed channel was reduced from ∼3.3 Å to ∼2.7 Å over the 11-ns MD simulation, indicating that this hydrophobic girdle has the potential to become the geometrically most restricting region in the closed channel. Another narrow region common to both initial closed and open models was located near the intracellular exit, but this narrow region in the closed channel was substantially widened after the 11-ns simulation, making the pore radius compatible to that in the same region of the open-channel.

Fig. 5.

(A) Pore-radius profiles of the TM2 region in the closed-channel (red) and open-channel (black) structures before (dash line) and after (solid line) 11-ns of MD simulations. The solid lines are average results of pore profiles over the last 100-ps simulations. The lowest water density was found in the region embracing pore lining residues α4-V259 (β2-V253) to α4-L263 (β2-L257) of the closed channel. (B) Snapshots of water (in red and white) occupancy inside the closed and open channels. For clarity, only the TM2 helices are shown. Pore profiles shown in blue were generated using HOLE program. Low water density in the aforementioned hydrophobic region in the closed channel is observable.

Water density distribution inside the channel also demonstrated considerable difference between closed and open sates of channel. Although water molecules distributed homogeneously in both channels at the beginning of MD simulations, the water density in the region between hydrophobic residues α4-V259, α4-L263 and their β2 homologous residues in the closed channel became significantly lower. The water density inside the hydrophobic girdles was almost four times less than that in the open-channel during the course of simulations. It appeared that the hydrophobic girdle was the “gate” for water passage. The same phenomena were also observed previously in similar systems.18,19,32

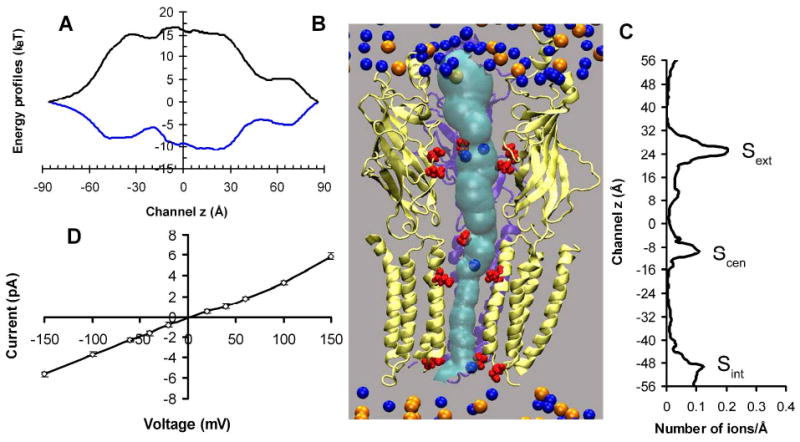

Channel energy barrier and Na+ permeation

Fig. 6A shows the energy profile experienced by a single Na+ or Cl− moving along the channel centerline through the α4β2 nAChR open model. The dielectric self energy (DSE) due to the spatial variation of the dielectric medium and the electrostatic energy contributed by the protein channel (see Eq. 3S in the supplementary materials) were included in the calculation of this energy profile. The energy barrier for a Cl− is 17 kBT, which essentially prevents the permeation of chloride ions. The energy well for a Na+ near the extracellular entrance of the transmembrane domain is around -10 kBT, indicating that α4β2 nAChR is selective to cations. An energy barrier of ∼ 8.0 kBT and ∼ 4.6 kBT at the aforementioned hydrophobic gate was determined for the closed- and open-channel models, respectively. The energy barrier calculated using our coarse-grained approach in the closed α4β2 nAChR is comparable to the energy barrier of 8.0 kBT for translocation of Na+ through the hydrophobic gate in the closed α7 TM domain calculated recently via a MD simulation.32 The dielectric constant for water inside the channel was assumed to be the same (εw = 80) in the DSE calculation for both open and closed channels. An even greater energy barrier would be produced if a smaller dielectric constant was assigned for the water inside the closed channel, which seems reasonable because much less of water was present in the hydrophobic girdle of the closed channel (cf. Fig. 5B). Although the energy barrier determined by the electrostatic continuum approach might not be very accurate for the closed channel due to the discontinuity of water occupancy near its hydrophobic gate region, the difference of energy barriers near the putative hydrophobic gate between these two channels was significant enough for suggesting potential roles of the hydrophobic residues in the channel gating.

Fig. 6.

(A) Single ion energy profiles experienced by Na+ (blue) and Cl− (black) governing permeation through the open channel. (B) A snapshot of BD simulation on Na+ (blue spheres) permeation in the open-channel. For clarity, only two α4 (yellow) and one β2 (violet) subunits are shown. The negatively charged pore lining residues are highlighted in red. The pore profile in cyan was calculated using the HOLE program. Orange spheres depict chloride ions. (C) Na+ occupancy along the channel z direction. Note that z=0 along the channel axis in this figure corresponds to z=15Å in Fig. 5. (D) Current-voltage relationship for a symmetrical bathing solution of 0.15 M NaCl obtained via BD simulation.

The characteristics of Na+ permeation in our open channel were investigated using a DMC algorithm34,56 to perform the BD simulations. Figs. 6B and 6C show our identified three Na+ binding sites inside the channel, which are in good agreement with what reported previously on MD simulations of nAChR.69 The ion density profile inside the channel was weakly dependent on the applied external potential. On average, there were two ions bound to the extracellular binding site (Sext) that was formed by β2-E103, α4-D102 and α4-D104, one Na+ bound to the central binding site (Scen) that was formed by β2-D268 (D28′) and α4-E266 (E20′), and one Na+ bound to the intracellular binding site (Sint) that was lined by α4-E245 (E-1′) and β2-E239 (E-1′). These predicted binding sites could be used experimentally to control the ion-flow through the channel via mutations. For example, our BD simulations suggested that neutralization of α4-E245 (E-1′) and β2-E239 (E-1′) decreased almost three times in conductance, but did not change the channel selectivity.

Fig. 6D illustrates the linear relationship of current-voltage (IV) in our open-channel model in a symmetric bathing solution of 0.15M NaCl, which agrees well with single-channel measurements.6,70 The simulated conductance of 38±3 pS is reasonably close to the experimental values of 40∼46 pS for α4β2 nAChR.6,70 The ion conductance is unique to individual subtype of nAChR, for example the α7 nAChR, a close relative of α4β2, has the experimental Na+ conductance of ∼ 80 pS.71 A movie of Na+ permeation is included in the supplementary materials. The same calculation was also performed on the closed-channel structure, showing approximately a factor of four reductions in the channel conductance. However, one might expect a much lower conductance in a fully closed channel. Comparing to the recent x-ray structure of a prokaryotic pentameric ligand-gated ion channel (minimum pores size <1.0Å),11 the channel in the EM structure of Torpedo nAChR (PDB: 2BG9) (minimum pore size ca. 2.4Å)3 is indeed not closed completely. Furthermore, a recent MD simulation69 showed that within 16 ns a single cation was transported through the closed adult human muscle nAChR (constructed via homology modeling based on Torpedo nAChR (2BG9)) at an applied external potential of -100 mV. Nevertheless, the functional distinction between our closed- and open-channel models is clear and substantial.

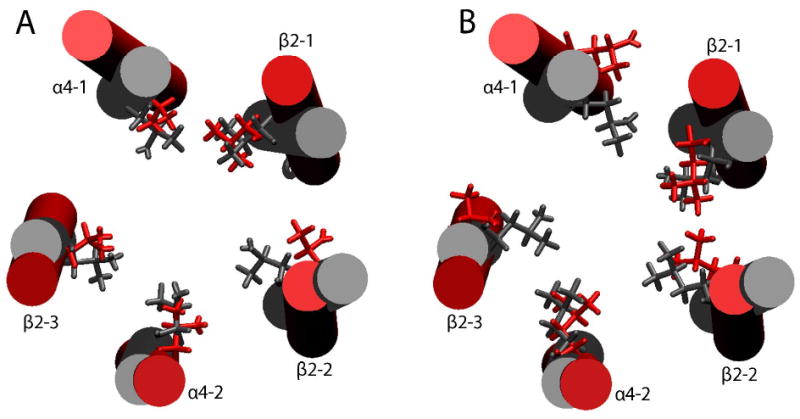

TM2 domain in channel opening

All aforementioned differences between our closed- and open channel structures might result predominately from the “twist to open” motion15,27-29 that was applied initially to the closed-channel model for generating the open-channel. However, both models could experience additional motions during the MD simulations that may contribute to the equilibrated structures. Neither closed nor open model had featured kinks in the middle of TM2 helices. The finding supports some previous observations30,59 but is in disagreement with others.16,17 Tilting of the TM2 helices was hypothesized previously to affect channel opening.12-15 Thus, we characterized the TM2 radial and lateral titling angles.59 We found that titling motions of five TM2 helices were not highly concerted or synchronized (Fig. 6S in the supplementary materials). A declining trend of TM2 lateral tilting angles in the open-channel was developed over the course of 11-ns MD simulations, but this trend did not correlate well with the change in TM2 radial tilting angles. On average, the TM2 tilting angles differed no more than 5° in the closed and open channel. Such a small difference seemed unlikely to be the key determinant for the channel opening of the α4β2 nAChR, but one should not rule out the possibility that small difference in TM2 titling may lead to a difference in side-chain orientation.

Orientation of pore-lining hydrophobic side-chains often controlled the channel opening. Fig. 7 compares the side-chain orientations of residues comprising putative hydrophobic gates in the closed- and open-channel structures. Notable sideward or outward swinging of the side-chains of V253 in β2-2 (Fig. 7A), L263 in α4-1 and L257 in β2-3 (Fig. 7B) made the pore size of the open-channel significantly larger than that of the closed channel in the region. It is clear that even without concerted side-chain swinging, the channel could be opened up by reorientation of one or two hydrophobic side-chains. Based on our data, kinking and tilting of the TM2 helices are not as significant as the outward rotation of the TM2 side-chains in gating. The most recent full structure simulation of the closed-channel α7 nAChR receptor implicated the tilting of the TM2 helices as the initiating factor to open the pore,59 therefore, our data suggest a different pore opening mechanism in the heteromeric α4β2 nAChR compared to its close relative, the homomeric α7 nAChR.

Fig. 7.

Orientation of the pore lining hydrophobic side-chains in the TM2 of the averaged closed-channel (gray) and open-channel (red) structures obtained from the last 100 ps of MD simulations. (A) α4-V259 and the homologous residues in β2; (B) α4-L263 and the homologous residues in β2. Notice the enlargement of the pore size in the open channel due to side-chains swinging away from the center of the pore. For clarity, the TM2 helices in the closed- and open-channel models were superimposed to demonstrate the side-chain orientation.

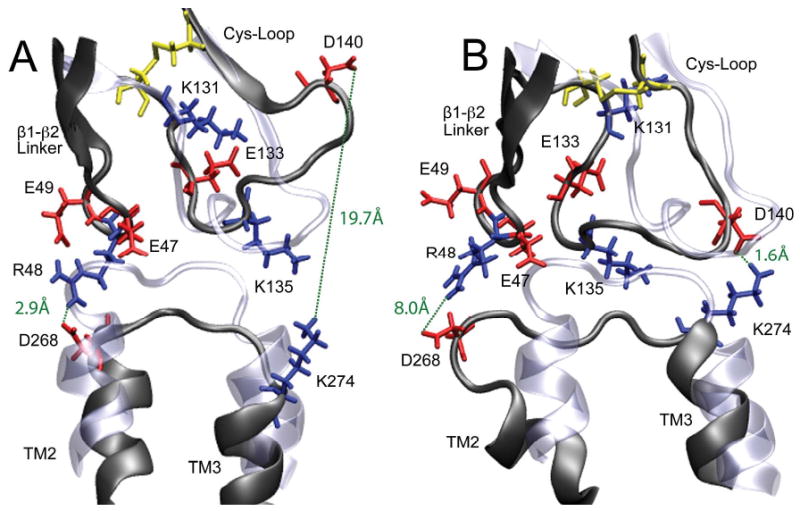

Charged residues at the gating interface and none-α subunits in channel gating

The agonist binding to the EC domains of the Cys-loop receptors induces a ‘cascade’ of conformational changes leading to channel opening. The coupling of agonist binding to channel gating is believed to proceed via two possible pathways. Although covalent bonding of the β10 strand in the EC domain and the TM1 helix is one possibility, interactions of the Cys-loop and β1-β2 linker in the EC domain with the linker connecting the TM2 and TM3 domains are more highly regarded as the pathway of signal propagation for channel gating.72-76 In a hetero-pentamer, such as α4β2 nAChR, it remains unclear whether the signaling of agonist binding occurs only within the α4 subunit because of its important C-loop contribution to the binding site or occurs as well in the adjacent β2 subunit due to its F-loop engagement to the binding site.

Interestingly, comparing our closed-channel structure to the open one, we found that β2 subunits experienced greater alternation in the EC-TM interface than α4 subunits. The Cys-loop of the β2-2 subunit in the closed-channel structure rotated ∼45° away from its initial orientation in the simulations, making the Cys-loop apart from the TM2-TM3 linker with the largest separation among all subunits (Fig. 8A). On the other hand, R48 of the β1-β2 linker was close enough to D268 of the TM2-TM3 linker to form a salt bridge. In contrast to the closed-channel structure, the Cys-loop of the β2-2 subunit in the open-channel (Fig. 8B) moved much closer to the TM2-TM3 linker soon after the protein backbone restrain was removed in the MD simulations. A salt bridge between D140 (Cys-loop) and K274 (TM2-TM3) was formed intermittently, but the one constituted by R48 and D268 disappeared due to a much larger separation of these two residues in the open channel than that in the closed-channel structure. Consequently, the β2-2 TM2 helix appeared to move downward for almost one helical turn, and its V253 side-chain rotated toward the side to widen the pore size, as depicted in Fig. 7. The open-channel β2-3 subunit also, to a lesser extent, demonstrated the same type of conformational changes at its EC-TM interface (the side-chain of the L257 residue in this subunit also rotated outward). These observations seem to suggest that β subunits could contribute to channel gating. In fact, β-TM2 conformational transitions upon agonist binding at the muscle nAChR were detected in previous fluorescence measurements.77 Moreover, a β2 subunit of the neuronal-nAChR was found critically important for characteristic behavior responses to nicotine in mice.78

Fig. 8.

Snapshots of the EC-TM interfacial region of the β2-2 subunit before (ice blue) and after (dark grey) 11-ns MD simulations. (A) The closed channel; (B) the open channel. Charged residues are colored in red (acidic) and blue (basic), the disulfide bridges are in yellow. Salt-bridge formation and breakage are highlighted in green dashed lines. Each β2 subunit could potentially form two pairs of salt-bridges between residues in the EC and TM2-TM3 interface: D140 (Cys-loop) and K274 (TM2-TM3 linker) or R48 (β1-β2 loop) and D268 (TM2-TM3 linker). These two pairs of salt bridge occurred alternatively but not simultaneously in the simulations.

Although alternation between formation and breakage of the salt bridge at the EC-TM interface, as revealed in the β2-2 subunit, might be sufficient to cause channel gating, it is not a necessary condition for gating. It has been elegantly demonstrated in the mutagenesis and electrophysiological studies that the overall charging pattern at the EC-TM interface, rather than the specific salt bridges, controls the gating process in the Cys-loop superfamily.72 In the case of α4β2, the β2 subunits could form a maximum of two salt bridges at the EC-TM interface, but the possibility of forming salt bridges in the same region of the α4 subunits does not exist due to lack of proper charged residue pairs. None of the salt bridges in the β2 subunits survived for 11-ns MD simulations, and at most one salt bridge at a time was formed in each β2 subunit (Fig. 7S in the supplementary materials). Therefore, specific salt bridges at the interface could not contribute to channel gating in a coherent phase among all subunits, but there is no evidence so far to suggest the necessity of in phase contribution to channel gating from all subunits or even same type of subunits. Nevertheless, charged residues at the EC-TM interface may facilitate the propagation of agonist binding signal from EC to TM domain, which was also implied in other studies.72,73,75

Considering the previously mentioned structural changes, we propose a plausible gating process composed of the following structural changes: the inward rotation of the Cys-loop to better engage the TM2-TM3 linker upon ligand binding; maximizing the hydrophobic packing of the Cys-loop and the TM2-TM3 linker followed by breakage and formation of the interfacial salt bridges; rotation and tilting of the TM2 helix; and consequently the outward rotation of the channel side-chains leading to the opening of the ion-channel. In other words, the Cys-loop behaves as an apparatus that controls the movements of the TM2 helix and thereby modulates channel gating.

Conclusions

The demand for high-resolution structures of the closed- and open-channel α4β2 nAChR is imperative because of the protein's biological and pharmacological importance, but the pace of progress in experimental structure determinations of the α4β2 nAChR, or any other member of the Cys-loop supperfamily, has not been able to match the urgent need for further protein structure information. The in silico models established in this study offer a good starting point for extrapolative research.

The quality of in silico models, or how well the models reflect “true” structures, is always in question until the “true” structures become available. However, multiple evaluations on the closed- and open-channel structures indicated that both models fairly reflect previously reported characteristics of the α4β2 or other nAChRs. The models developed herein should prove useful for many potential applications, such as predicting drug targets and understanding the channel gating mechanism. Our model was successful in predicting mutations to the transmembrane domain of the α4 subunit that better stabilize that domain in detergent micelles. In particular, our model clearly showed protection of hydrophobic residues in the TM2-TM3 linker by interaction with the extracellular domain. Mutation of this hydrophobic patch to a more polar sequence stabilized the structure of the transmembrane domain expressed in isolation. The mutated domain is much more stable for structural determination by experimental solution NMR (in progress).

Many insights related to channel gating were revealed in this study. Although it was known that TM2 played a critical role in channel gating, our data explicitly demonstrated that non-synchronized TM2 movement probably was a more realistic mode of action for channel gating. Rotation and titling of individual TM2 helices could lead changes in side-chain orientations of pore-lining residues. Without concerted movement, one or two hydrophobic side-chain reorientation was enough for channel opening. The closed- and open-channel structures exhibited distinct patterns of electrostatic interactions at the EC-TM interface that might regulate the signal propagation of agonist binding to channel opening. A potential prominent role of β2 subunit in channel gating was elucidated in our study and is worth pursuing further in the future. This observation appears to be different from that in a muscle-type nAChR, for which Unwin suggested that conformational changes of the α subunit led to gating.3 Particularly, the experimental mutations of the two charged-pair residues at the EC-TM interface of the β2 subunits that are not present in the α4 subunits, R48-D268 and D140-K274, could provide insights about the level of the β2 involvement in the channel opening; while presumably the ligand binding site is on the α4 subunit.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Troy Wymore and Mr. Adam C. Marko for their assistance in the initial modelling. This research was supported in part by the National Science Foundation through TeraGrid resources provided by the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center. TeraGrid systems are hosted by Indiana University, LONI, NCAR, NCSA, NICS, ORNL, PSC, Purdue University, SDSC, TACC and UC/ANL. This research was supported in part by grants from NIH (R01GM066358, R01GM056257, and R37GM049202) and NSF (CHE-0518044).

Contributor Information

Esmael J. Haddadian, Email: ejh21@pitt.edu.

Mary Hongying Cheng, Email: chengh@mercury.chem.pitt.edu.

Rob D Coalson, Email: rob@mercury.chem.pitt.edu.

Yan Xu, Email: xuy@anes.upmc.edu.

Pei Tang, Email: tangp@anes.upmc.edu.

References

- 1.Sine SM, Engel AG. Nature. 2006;440:448. doi: 10.1038/nature04708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lester HA, Dibas MI, Dahan DS, Leite JF, Dougherty DA. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:329. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Unwin N. J Mol Biol. 2005;346:967. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tapper AR, McKinney SL, Nashmi R, Schwarz J, Deshpande P, Labarca C, Whiteaker P, Marks MJ, Collins AC, Lester HA. Science. 2004;306:1029. doi: 10.1126/science.1099420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Court JA, Martin-Ruiz C, Graham A, Perry E. J Chem Neuroanat. 2000;20:281. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(00)00110-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buisson B, Gopalakrishnan M, Arneric SP, Sullivan JP, Bertrand D. J Neurosci. 1996;16:7880. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-24-07880.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brejc K, van Dijk WJ, Smit AB, Sixma TK. Novartis Found Symp. 2002;245:22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Celie PH, van Rossum-Fikkert SE, van Dijk WJ, Brejc K, Smit AB, Sixma TK. Neuron. 2004;41:907. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Celie PH, Kasheverov IE, Mordvintsev DY, Hogg RC, van Nierop P, van Elk R, van Rossum-Fikkert SE, Zhmak MN, Bertrand D, Tsetlin V, Sixma TK, Smit AB. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:582. doi: 10.1038/nsmb951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyazawa A, Fujiyoshi Y, Unwin N. Nature. 2003;423:949. doi: 10.1038/nature01748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hilf RJ, Dutzler R. Nature. 2008;452:375. doi: 10.1038/nature06717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang P, Mandal PK, Xu Y. Biophys J. 2002;83:252. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75166-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paas Y, Gibor G, Grailhe R, Savatier-Duclert N, Dufresne V, Sunesen M, de Carvalho LP, Changeux JP, Attali B. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507599102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cymes GD, Ni Y, Grosman C. Nature. 2005;438:975. doi: 10.1038/nature04293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szarecka A, Xu Y, Tang P. Proteins. 2007;68:948. doi: 10.1002/prot.21462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cymes GD, Grosman C, Auerbach A. Biochemistry. 2002;41:5548. doi: 10.1021/bi011864f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hung A, Tai K, Sansom MS. Biophys J. 2005;88:3321. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.052878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saladino AC, Xu Y, Tang P. Biophys J. 2005;88:1009. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.053421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beckstein O, Sansom MS. Phys Biol. 2006;3:147. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/3/2/007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson G, Karlin A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:1241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.031567798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson GG, Karlin A. Neuron. 1998;20:1269. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80506-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hillisch A, Pineda LF, Hilgenfeld R. Drug Discov Today. 2004;9:659. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03196-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen SW, Pellequer JL. Curr Med Chem. 2004;11:595. doi: 10.2174/0929867043455891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chou KC. Curr Med Chem. 2004;11:2105. doi: 10.2174/0929867043364667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldsmith-Fischman S, Honig B. Protein Sci. 2003;12:1813. doi: 10.1110/ps.0242903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tobi D, Bahar I. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507603102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taly A, Delarue M, Grutter T, Nilges M, Le Novere N, Corringer PJ, Changeux JP. Biophys J. 2005;88:3954. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.050229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng X, Lu B, Grant B, Law RJ, McCammon JA. J Mol Biol. 2006;355:310. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taly A, Corringer PJ, Grutter T, Prado de Carvalho L, Karplus M, Changeux JP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607477103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Law RJ, Henchman RH, McCammon JA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:6813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407739102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu Y, Barrantes FJ, Luo X, Chen K, Shen J, Jiang H. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:1291. doi: 10.1021/ja044577i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ivanov I, Cheng X, Sine SM, McCammon JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:8217. doi: 10.1021/ja070778l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corry B. Biophys J. 2006;90:799. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.067868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheng MH, Cascio M, Coalson RD. Biophys J. 2005;89:1669. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.060368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suhre K, Sanejouand YH. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W610. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng MH, Liu LT, Saladino AC, Xu Y, Tang P. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:14186. doi: 10.1021/jp075467b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gasteiger E, Gattiker A, Hoogland C, Ivanyi I, Appel RD, Bairoch A. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3784. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fiser A, Do RK, Sali A. Protein Sci. 2000;9:1753. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.9.1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guex N, Peitsch MC. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:2714. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150181505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anand R, Lindstrom J. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:4272. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.14.4272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Phillips JC, Braun R, Wang W, Gumbart J, Tajkhorshid E, Villa E, Chipot C, Skeel RD, Kale L, Schulten K. J Comput Chem. 2005;26:1781. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laskowski RA, Moss DS, Thornton JM. J Mol Biol. 1993;231:1049. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tirion MM. Phys Rev Lett. 1996;77:1905. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Valadie H, Lacapcre JJ, Sanejouand YH, Etchebest C. J Mol Biol. 2003;332:657. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00851-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smart OS, Neduvelil JG, Wang X, Wallace BA, Sansom MS. J Mol Graph. 1996;14:354. doi: 10.1016/s0263-7855(97)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang F, Imoto K. Proc Biol Sci. 1992;250:11. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1992.0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barrantes FJ. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2004;47:71. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.MacKerell AD, Bashford D, Bellott M, Dunbrack RL, Evanseck JD, Field MJ, Fischer S, Gao J, Guo H, Ha S, Joseph-McCarthy D, Kuchnir L, Kuczera K, Lau FTK, Mattos C, Michnick S, Ngo T, Nguyen DT, Prodhom B, Reiher WE, Roux B, Schlenkrich M, Smith JC, Stote R, Straub J, Watanabe M, Wiorkiewicz-Kuczera J, Yin D, Karplus M. J phys Chem B. 1998;102:3586. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hoover WG. Phys Rev A. 1985;31:1695. doi: 10.1103/physreva.31.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nose SJ. Chem Phys. 1984;81:511. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brünger A. X-PLOR, Version 3.1: A system for X-ray crystallography and NMR. Yale University; New Haven: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Darden T, York D, Pedersen L. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:10089. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morris GM, Goodsell DS, Halliday RS, Huey R, Hart WE, Belew RK, Olson AJ. J Comput Chem. 1998;19:1639. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dundas J, Ouyang Z, Tseng J, Binkowski A, Turpaz Y, Liang J. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W116. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cheng MH, Mamonov AB, Dukes JW, Coalson RD. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:5956. doi: 10.1021/jp063993h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Graf P, Nitzan A, Kurnikova MG, Coalson RD. J Phys Chem B. 2000;104:12324. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. J Mol Graph. 1996;14:33. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cheng X, Ivanov I, Wang H, Sine SM, McCammon JA. Biophys J. 2007;93:2622. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.109843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kurnikova MG, Coalson RD, Graf P, Nitzan A. Biophys J. 1999;76:642. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77232-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hamouda AK, Sanghvi M, Chiara DC, Cohen JB, Blanton MP. Biochemistry. 2007;46:13837. doi: 10.1021/bi701705r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grandl J, Danelon C, Hovius R, Vogel H. Eur Biophys J. 2006;35:685. doi: 10.1007/s00249-006-0078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Grosman C, Auerbach A. J Gen Physiol. 2000;115:637. doi: 10.1085/jgp.115.5.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hansen SB, Sulzenbacher G, Huxford T, Marchot P, Taylor P, Bourne Y. EMBO J. 2005;24:3635. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Karlin A. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:102. doi: 10.1038/nrn731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jackson MB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:2199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.7.2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhong W, Gallivan JP, Zhang Y, Li L, Lester HA, Dougherty DA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:12088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cheng X, Wang H, Grant B, Sine SM, McCammon JA. PLoS Comput Biol. 2006;2:e134. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang HL, Cheng X, Taylor P, McCammon JA, Sine SM. PLoS Computational Biology. 2008;4:e41. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0040041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rodrigues-Pinguet NO, Pinguet TJ, Figl A, Lester HA, Cohen BN. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68:487. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.011155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fucile S, Palma E, Martinez-Torres A, Miledi R, Eusebi F. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:3956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052699599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xiu X, Hanek AP, Wang J, Lester HA, Dougherty DA. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:41655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508635200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bouzat C, Gumilar F, Spitzmaul G, Wang HL, Rayes D, Hansen SB, Taylor P, Sine SM. Nature. 2004;430:896. doi: 10.1038/nature02753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chakrapani S, Bailey TD, Auerbach A. J Gen Physiol. 2004;123:341. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200309004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kash TL, Jenkins A, Kelley JC, Trudell JR, Harrison NL. Nature. 2003;421:272. doi: 10.1038/nature01280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Grosman C, Salamone FN, Sine SM, Auerbach A. J Gen Physiol. 2000;116:327. doi: 10.1085/jgp.116.3.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dahan DS, Dibas MI, Petersson EJ, Auyeung VC, Chanda B, Bezanilla F, Dougherty DA, Lester HA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0301885101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Maskos U, Molles BE, Pons S, Besson M, Guiard BP, Guilloux JP, Evrard A, Cazala P, Cormier A, Mameli-Engvall M, Dufour N, Cloez-Tayarani I, Bemelmans AP, Mallet J, Gardier AM, David V, Faure P, Granon S, Changeux JP. Nature. 2005;436:103. doi: 10.1038/nature03694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.