Abstract

All striated muscles respond to stretch by a delayed increase in tension. This physiological response known as stretch-activation is, however, predominately found in vertebrate cardiac muscle and insect asynchronous flight muscles. Stretch-activation relies on an elastic third filament system composed of giant proteins known as titin in vertebrates or kettin and projectin in insects. The projectin insect protein functions jointly as a ‘scaffold and ruler’ system during myofibril assembly, and as an elastic protein during stretch activation. An evolutionary analysis of the projectin molecule could potentially provide insight into how distinct protein regions may have evolved in response to different evolutionary constraints. We mined candidate genes in representative insect species from Hemiptera to Diptera, from published and novel genome sequence data and carried out a detailed molecular and phylogenetic analysis. The general domain organization of projectin is highly conserved, as are the protein sequences of its two repeated regions—the Immunoglobulin type C and Fibronectin type III domains. The conservation in structure and sequence is consistent with the proposed function of projectin as a scaffold and ruler. In contrast, the amino acid sequences of the elastic PEVK domains are noticeably divergent although their length and overall unusual amino acid makeup are conserved. These patterns suggest that the PEVK region working as an unstructured domain can still maintain its dynamic, and even its three-dimensional properties, without the need for strict amino acid conservation. Phylogenetic analysis of the projectin proteins also supports a reclassification of the Hymenoptera in relation to Diptera and Coleoptera

Keywords: projectin, titin, elastic protein, modular protein, muscle, flight, insect evolution, PEVK

INTRODUCTION

Insect flight muscles can be classified as either synchronous or asynchronous based on differences in their physiology and ultrastructure (Pringle, 1949; 1978; 1981). For example, synchronous muscles display a characteristic 1:1 ratio between nervous excitation and contraction, whereas asynchronous indirect flight muscles (IFM) exhibit multiple contractions for each nerve impulse. The asynchronous mode depends on a delayed increase in tension brought about by stretch (stretch-activation), a physiological response associated with the high resting stiffness of the muscle fibers (reviewed by Josephson et al 2000; Moore, 2006). Although observed in nearly all muscles, stretch activation is uniquely enhanced in insect asynchronous flight muscles and vertebrate cardiac muscles.

Several molecular models of stretch-activation have implicated the insect C-filament system and its vertebrate counterpart (titin filaments) in providing the high resting stiffness necessary for sensing and transducing stretch to the actin-myosin lattice (Granzier and Wang, 1993; Kulke et al, 2001; Vigoreaux et al, 2000; Fukuda and Granzier, 2005; reviewed in Trombitas, 2000 and Moore, 2006). The current model for C-filaments in Drosophila proposes primarily two constituent proteins: kettin (and its longer isoform Sallimus (Sls)), and projectin (Bullard et al, 2000; 2005; 2006). Consistently, flies containing mutations in either projectin or Sls are respectively flight impaired and flightless (Moore et al, 1999; Hakeda et al, 2000; Kolmerer et al, 2000).

Projectin is a sizeable (~1,000 kDa) myofibrillar protein (Saide et al, 1989; Lakey et al, 1990; Trombitas, 2000; Bullard et al, 2005) composed largely of two repeated motifs— Fibronectin III (FnIII) and Immunoglobulin (Ig) —arranged in a regular pattern [Fn-Fn-Ig] within its central core region (Ayme-Southgate et al, 1991; 1995; Fyrberg et al, 1992; Daley et al, 1998). In contrast, the COOH- and NH2-termini contain Ig motifs yet lack FnIII domains. FnIII and Ig domains have been implicated in numerous examples of protein-protein interactions (reviewed in Gautel, 1996), and the projectin protein is, therefore, proposed to serve as a scaffold for myofibril assembly through its interactions with the myosin filament. Projectin also includes several different non-repeated amino acid sequences. One of these was initially characterized as analogous to titin PEVK because of its atypically high percentage of proline, glutamic acid, valine and lysine (Southgate and Ayme-Southgate, 2001). The PEVK domain is located within the NH2-terminus of the protein between two separate segments composed of eight and six Ig domains respectively. In D. melanogaster IFM, projectin is aligned along the sarcomeric unit with its NH2-terminus embedded within the Z band while its central core region is likely associated with the myosin filament (Ayme-Southgate et al, 2000; 2005). This orientation suggests that the projectin PEVK domain, together with some of the NH2-terminal Ig domains, can physically span the entire I-band (Ayme-Southgate et al, 2005; Bullard et al, 2005). The presence of a PEVK region and the distribution of PEVK and Ig domains over the I band of IFM muscles are consistent with projectin serving as an elastic protein during stretch activation.

However, the molecular mechanism(s) underlying length-dependent stretch activation are still not fully understood. In particular, several independent studies have been unable to correlate the protein composition of the myofibrils with the ability to generate stretch-activation. For example the protein arthrin was originally characterized only in asynchronous muscle myofibrils (Bullard et al, 1985), yet subsequently a more thorough investigation did not consistently found arthrin within all insect orders that are associated with asynchronous muscles (Schmitz et al, 2003). Troponin C is another such potential candidate where one isoform has been found to be specific to asynchronous flight muscle and sensitive to stretch in Lethocerus, Drosophila, and Anopheles (Qiu et al, 2003). However, a thorough investigation of more basal insect orders has not been performed for this protein.

Projectin cannot be thought of as an asynchronous muscle-specific protein, as it is found in both synchronous and asynchronous insect muscles and crustacean muscles (Nave and Weber, 1990; Vigoreaux et al, 1991; Oshino et al, 2003) and is considered an ortholog of the C. elegans myofibrillar protein, twitchin (Benian et al, 1989). However, there are several significant differences between the projectin isoforms present in asynchronous and synchronous muscle types of D. melanogaster. The localization of projectin differs as it is immunofluorescently localized exclusively over the A band in synchronous muscles, but is found over the I band in asynchronous muscles (Vigoreaux et al, 1991). The IFM isoform is also notably shorter, most likely as a consequence of alternative splicing within specific regions of the transcript, in particular the PEVK domain (Southgate and Ayme-Southgate, 2001), and size variants of titin PEVK specifically correlates with differences in the resting tension of vertebrate muscle fibers (Linke et al, 1999; Freiburg et al, 2000;Granzier et al, 2000; Fukuda and Granzier, 2005, reviewed in Granzier and Labeit, 2004). Here, we conducted an evolutionary analysis using both published and novel genomic sequence data to determine the changes in projectin sequences across several insect orders in order to provide insight into how different regions of the protein may have changed under different evolutionary constraints related to the various functions attributed to projectin.

Materials and Methods

Gene query and manual annotation

BLAST searches (Altschul et al, 1990; 1997) using sequences from the D. melanogaster core region (containing both Ig and Fn domains in a regular [Fn-Fn-Ig] pattern) were used to query available genome assemblies, contigs or trace archives. Apis mellifera, Tribolium castaneum, and Anopheles gambiae genomes were at the stage of annotated genomes when the study began whereas the Drosophila virilis, Drosophila ananassae, Drosophila pseudoobscura, Aedes aegyptii, and Nasonia vitripennis genomes were assembled, but not annotated. The following annotated genes/ contigs were initially retrieved: A. mellifera: ENSAPMG00000008141 and ENSAPMP00000014257; T. castaneum: CM000276.1/ GLEAN_04721; A. gambiae: ENSANGG00000014893; A. aegyptii: LOCUS: AAGE02003896; D. virilis: scaffold_13052; D.pseudoobscura: group8, and N. vitripennis: scaffold113. In many cases, genomic data retrieved from annotated genomes include the predicted splicing pattern of the candidate gene and its derived translation data. Predicted cDNA and amino acid sequences were compared against the D. melanogaster amino acid sequences to identify missing domains or incorrect splice patterns. Regions not included in the initial annotation were manually annotated from available surrounding genomic sequences.

The Acyrthosiphon pisum genome was completed, but not assembled, and only trace archives were available. The A. pisum trace results from BLAST searches were assembled into contigs using Vector NTI software (Invitrogen™), and overlapping contigs were joined to generate a semi-contiguous genomic sequence when possible. Assembled contig sequences were translated in all three forward frames and translation results were aligned against D. melanogaster amino acid sequences using LaLign (Huang and Miller, 1991). This allowed for manual annotation of the putative exon-intron splicing pattern over most of the gene. Although, the PEVK domain could not be resolved using this approach.

RNA extraction and RT-PCR sequencing

Total RNA was purified from whole (live or frozen) animals, using Trizol (Invitrogen™). Apis mellifera was obtained from Dr. J. Evans (USDA, Beltsville, MD), Tribolium castaneum from Dr. S. Brown (Kansas State University, KS), Nasonia vitripennis from Dr. J. Werren (University of Rochester, NY), Acyrthosiphon pisum from Dr. D. Stern (Princeton U., NJ), and D. virilis, D. pseudoobscura from the Tucson Drosophila stock center. Isolated RNAs were used in RT-PCR reactions (Superscript™ One-Step RT-PCR mix from Invitrogen™) with gene-specific primers designed from potential exons or predicted ORFs as previously described (Southgate and Ayme-Southgate, 2001). PCR amplified cDNA products were separated by gel-electrophoresis and either sequenced directly or subcloned into the pGEM-T-easy™ vector (Promega Inc.; DNA Core Facility, Medical University of SC, MUSC). The cDNA sequences were manually aligned by comparison to the genomic sequences to identify and verify putative splice site positions.

Bioinformatics analysis of projectin sequences

Multiple sequence alignments (MSA) were performed using the CLUSTALW algorithm (Thompson et al, 1994; 1997) and checked by eye within Jalview. Gaps originating from differences in the domain pattern, for example the missing exon in mosquitoes, or gaps representing incomplete analysis, such as the PEVK domains in some species, were manually removed from the alignment when the entire sequences were compared. Two methods—maximum parsimony using ProtPars (Felsenstein, 1989; 1996) and maximum likelihood using PhyML (Guindon et al, 2003; 2005)—were used to derive evolutionary tree(s). ProtTest analysis determined that the most appropriate model of evolution was RtREV (Abascal et al, 2005; 2007), yet for phylogenies we expanded this to include additional models of evolution (JTT, RtREV, and WAG; Jones et al, 1992; Dimmic et al, 2005; Whelan and Goldman 2001 respectively). The robustness of parsimony-based and likelihood-based phylogenies was assessed using 1000 to 2000 bootstrap replicates and summarized using Consense (Phylip package; Felsenstein, 1989). C. elegans twitchin (Benian et al, 1989) or crayfish (Procambarus clarkii) projectin sequences (Oshino et al, 2003) were used as outgroup sequences in the phylogenetic trees and the tree output was visualized using TreeView (Page, 1996). Additionally, diagonal graphical alignments between pairs of sequences were generated using Dotlet (Junier and Pagni, 2000) and manually evaluated.

RESULTS

Characterization of the projectin gene in different insect species

The projectin gene was identified in the genomes of the following insects for which genome projects were either underway or completed: Diptera: Drosophila virilis, Drosophila ananassae, Drosophila pseudoobscura, Anopheles gambiae (mosquito / malaria), and Aedes aegyptii (mosquito / yellow fever); Hymenoptera: Apis mellifera (honeybee) and Nasonia vitripennis (jewel wasp); Coleoptera: Tribolium castaneum (red flour beetle); and Hemiptera: Acyrthosiphon pisum (pea aphid). All of these insects possess asynchronous flight muscles.

Typically, BLAST searches were done with a sequence from the projectin core region of D. melanogaster (containing both Ig and FnIII domains) to query available genome assemblies, contigs or trace archives (see Materials and Methods). We determined whether candidate sequences identified using this approach were for projectin orthologs rather than for other Ig domain-containing proteins (such as stretchin or kettin/Sls; Champagne et al, 2000; Kolmerer et al, 2000) by verifying that they contain the [Fn-Fn-Ig] characteristic pattern of the core region of projectin. For example, kettin does not possess any FnIII domains and its longer Sls isoform contains only a few FnIII domains near its COOH-terminus.

As a result of this initial search we retrieved the A. mellifera and A. gambiae projectin orthologs, but determined that the sequences equivalent to the D. melanogaster NH2-terminus and PEVK domains were not included in the initial gene builds. We retrieved adjacent 5′ genomic sequences and the exon-intron pattern of the NH2-terminus was manually annotated by alignment of the translation data with D. melanogaster sequences, together with matches to Expressed Sequence Tag (EST) sequences when available. If necessary, the predicted exon-intron pattern was confirmed by RT-PCR analysis (see Materials and Methods). The D. virilis, D. pseudoobscura, D, ananassae, A. aegyptii, and N. vitripennis genomes were assembled, but not annotated, so we manually annotated the exon-intron splicing of all regions except for the PEVK domain using alignment to the Drosophila or Apis (for Nasonia) amino acid sequences. Any ambiguities were further resolved by RT-PCR analysis (see Materials and Methods). For the A. pisum genome, only trace archives were available, and BLAST searches returned a total of 315 trace archives, which were assembled to generate most of the A. pisum projectin gene (see Materials and Methods). There are still gaps for which we could not retrieve any traces, but all of these missing sequences are found within introns. Since the start of this project, the first assembly of the A. pisum genome has been released, and the projectin genomic sequence we generated is identical to the genomic sequence found in the assembly (some of the gaps still exist). As before, the exon-intron splicing of all regions except for the PEVK domain was established using alignment of EST matches to the genomic sequence, comparison of the translation products for homology to other projectin sequences. Ambiguities were further resolved by RT-PCR analysis (see Materials and Methods).

Following this initial annotation, genomic sequences found between Ig8 and Ig9 in each of these genes were considered potential PEVK regions. Because of low homology (see below) they could not be manually annotated, and the coding regions were identified by RT-PCR as previously performed in D. melanogaster (Southgate and Ayme-Southgate, 2001).

The characterization of the projectin genes and their exon-intron splicing is complete in five insect species representing four orders: Acyrthosiphon pisum (pea aphid; Hemiptera), Tribolium castaneum (red flour beetle; Coleoptera), Apis mellifera (honeybee; Hymenoptera), Nasonia vitripennis (jewel wasp; Hymenoptera), and Drosophila virilis (Diptera). We also have almost complete characterization in Drosophila pseudoobscura, Drosophila ananassae, Anopheles gambiae and Aedes aegyptii, where the entire gene except for parts of the PEVK domain has been annotated.

General motif pattern within the projectin proteins

All characterized projectin genes, apart from the two mosquito genes, contain 39 copies of both the Ig and the FnIII domains, as previously identified in D. melanogaster. Multiple alignments with D. melanogaster sequences demonstrate that the Ig18-Fn9-Fn10 block is missing from the core domain of A. gambiae and A. aegyptii genes (data not shown). In Drosophila species and in T. castaneum this module is in fact a one-exon entity, allowing for the loss of these three domains without actually affecting the open reading frame. The loss of this specific exon must have occurred at some point after the Drosophila and Culicidae lineages separated.

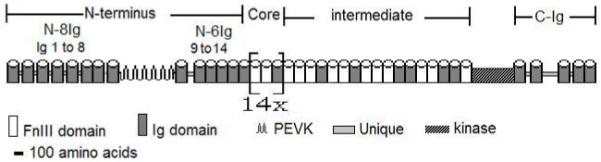

In all studied genes, the Ig and Fn domains are organized in the same basic pattern and order, as in D. melanogaster (see Figure 1). This arrangement defines five distinct regions within the protein. In the NH2-terminal the PEVK region separates two tracts of Ig domains containing eight (N-8Ig) and six (N-6Ig) Ig domains respectively. The core is composed of 14 repeats of the [Fn-Fn-Ig] module. Finally, the intermediate region has a conserved, but non-modular arrangement of FnIII and Ig domains, while the COOH-terminal contains five Ig domains (C-Ig). A similar pattern has also been found in groups more ancestral than the insect lineage including (i) the crayfish (P. clarkii) sequence, which is similar except for the presence of seven rather than eight Ig domains in the initial NH2-terminal region (Oshino et al, 2003, see below), and (ii) the C. elegans twitchin protein, which has a similar arrangement, but with a lower number of the two domains in all its regions (Benian et al 1989; 1993). The projectin protein contains two other non-repeated regions, the kinase and the PEVK domains (Figure 1, see below), which are not composed of either Ig or FnIII motifs.

FIGURE 1.

Complete domain structure of the projectin protein.

Schematic representation of the domain composition for the complete Drosophila melanogaster projectin protein. The Ig and FnIII domains are represented as barrels to reflect their globular nature. The [Fn-Fn-Ig] module is repeated 14 times within the central core region. The NH2-terminus is composed of 14 Ig domains separated by the PEVK region into two stretches of 8 (N8Ig) and 6 (N6Ig) Ig domains. The position of other regions, such as the kinase domain, the PEVK region, and several shorter unique sequences are also indicated. The PEVK region is represented as a spring-like structure so as to symbolize its suggested role in conferring elasticity to the protein.

Exon-intron pattern of the projectin genes

Because of the modular nature of the projectin protein, the relationship between exons and the boundaries of the Ig and FnIII domains was examined. Even though there are examples of a single domain encoded by a single exon in all the studied species, such instances are more frequent in A. pisum (23 examples) and A. mellifera (24 examples) than in T. castaneum (14 examples) or Drosophila sp (only three examples). In A. pisum, single domains are frequently split between two exons (25 domains split between two exons), with seven such occurrences in A. mellifera and only two domains split between two exons in Drosophila sp. Conversely, no exons in A. pisum contain more than one complete domain, whereas six such exons are present in A. mellifera containing two to four complete domains, and 32 domains (both Ig and FnIII) are included within the largest exon of Drosophila sp. (Supplemental Materials 1).

Because of its remarkably conserved protein organization, the complete projectin cDNA sequences of the insects characterized in this study are all similar in size, ranging from 26 to 27 kb in length (Table 1). In contrast, the size of the genomic sequences differs considerably (from 51 to greater than 70 kb), a difference attributable to both the number and size of the introns (Supplemental Materials-1). As summarized in Table 1, the number of exons is variable, ranging from 41 in D. virilis to 144 in A. pisum, reflecting a reduction in the number of introns as one progresses from more basal (A. pisum) to more derived (Drosophila sp.) insect lineages. Most of the documented intron losses occurred within the core and intermediate regions of the gene. For insects that are more closely related, such as the different Drosophila species and the A. mellifera/N. vitripennis pair, the number of exons and the position of the splice sites are more similar, even when the size of their corresponding introns differs significantly (Supplemental Materials-1).

TABLE 1.

Gene data

This table summarizes the main information on gene and cDNA sizes, as well as the number and size of exons for the insect projectin genes described in this study together with the Drosophila melanogaster gene. cDNA sizes are calculated from the initiation to the termination codons and do not include possible 5′ and 3′ UTR. na and > sign indicate that the information for that gene is incomplete due to the lack of characterization of the PEVK domain in that species.

| Dmel | Dvir | Dpse | Agam | Aaeg | Nvi | Amel | Tcas | Api | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gene size (bp) | 51,073 | 51,490 | >39,641 | >31,000 | >58,353 | 48,634 | 66,952 | 37,040 | >70,000 |

| cDNA size (bp) | 27,154 | 26,867 | 24,338 | 23,809 | 24,215 | 26,547 | 26,012 | 26,184 | 26,132 |

| # exons | 46 | 45 | >40 | >27 | >27 | 71 | 96 | 64 | 144 |

| largest exon (bp) | 9,462 | 9,474 | 9,474 | 10,046 | 11,964 | 4,371 | 2,325 | 2,670 | 1,054 |

| smallest exon (bp) | 22 | 22 | 22 | na | na | 22 | 15 | 22 | 22 |

| Amino acids # | 8,923 | 8,847 | > 8,258 | > 7,957 | > 8,068 | 8,912 | 8,730 | 8,379 | 8,607 |

| Calculated MW | 998,292 | 990,025 | >922,695 | >892,182 | >907,283 | 995,868 | 995,346 | 933,354 | 960,331 |

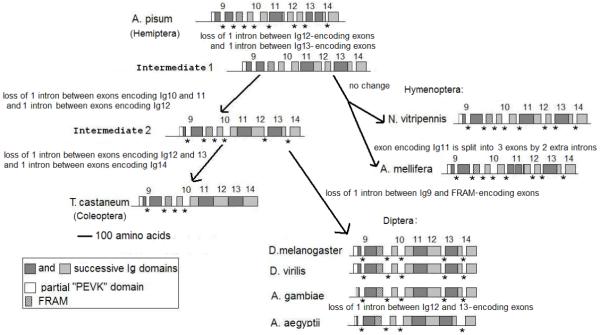

A thorough comparison of the position of splice sites throughout the entire projectin genes was carried out. As an example, we present an analysis of the genomic sequence encoding the N-6Ig region, and one scenario (out of several alternatives) by which the observed pattern of intron losses could have occurred (Figure 2). In this genomic region there are 10 introns in the A. pisum gene; eight of which are still found in the hymenopteran genes but only five are still present in both T. castaneum and the Diptera (with only four in A. aegyptii). As a possible alternative, for example intermediate 1 in Figure 2 could be (i) more ancestral to A. pisum, and (ii) A. pisum could have acquired two additional introns within the Ig12 and 13-encoding exons. Regardless of the true evolutionary scenario, the splicing pattern of the two hymenopteran genes indicates that the positions of certain splice sites (in particular between exons encoding Ig10 and 11 and between exons encoding Ig12) are identical to the splice sites found in A. pisum, suggesting that additional intron removal events would have occurred to yield the intron patterns in T. castaneum and in Diptera (Figure 2). This observation holds true when other regions of the projectin genes are examined (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

Proposed scenario for intron losses within the N-6Ig-coding region.

Schematic diagram of the different exons comprising the N-6Ig-coding region of the projectin genes, together with a possible scenario to account for intron losses derived from the basal A. pisum gene. Numbers above each exon indicate the encoded Ig domain. FRAM is a unique conserved sequence found between Ig9 and Ig10. * indicates conserved splice sites from the basal A. pisum gene. Note: introns are not drawn to scale.

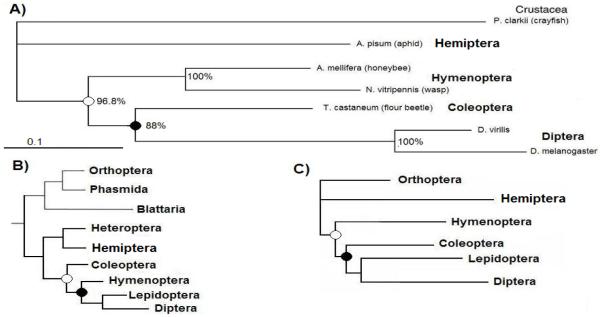

Until recently, accepted lineages of insect orders indicated that the Coleoptera was ancestral to the lineage that led to Hymenoptera and Diptera (for example Wheeler et al, 2001; reviewed in Beutel and Pohl, 2006; Figure 3B). Based on our observations, if this phylogeny was correct, the exact same exon fusion events would have had to occur independently in Coleoptera and in Diptera after the divergence from Hymenoptera. Alternatively, persistence of these “ancestral” introns in the available Hymenoptera projectin genes could indicate that the relative position of the Hymenoptera in the reconstruction of insect evolutionary history should be reconsidered, consistent with more recent studies (Savard et al, 2006; Krauss et al, 2008).

FIGURE 3.

Generated phylogenetic tree of the arthropod projectin proteins. A) The amino acid sequences of the full-length proteins were aligned using CLUSTALW and the maximum likelihood tree is presented. The crayfish projectin sequence was used to root the tree. Support values expressed in percent for each internal branch were obtained with 2,000 bootstrap steps. The scale bar corresponds to 0.1 estimated amino acid substitutions per site. B) Insect phylogeny according to Wheeler et al, 2001; C) Insect phylogeny according to Savard et al, 2006.

Phylogenetic relation of the projectin proteins

To address these alternatives, we investigated the phylogenetic relationships among insect orders for which we had projectin sequences. The analysis was carried out using (i) the whole amino acid sequence for insects with completed PEVK data or (ii) using individual protein regions such as the core, kinase, and C-terminal regions for all studied insects. We also conducted phylogenetic analysis using either Apis mellifera or Nasonia vitripennis sequences. These various alignments were evaluated under multiple models of evolution using maximum likelihood or maximum parsimony analyses (See Materials and Methods for details, aligned sequences are presented in the Supplemental Materials-2). Irrespective of the computational method, evolutionary model, or sequence combinations used, a concordant tree with nodal support of at least 80% was consistently generated (Figure 3A). This phylogeny supports a more basal position of the Hymenoptera in relation to the Coleoptera that is consistent with recent reports from Savard et al (2006) and Krauss et al (2008) (Figure 3C).

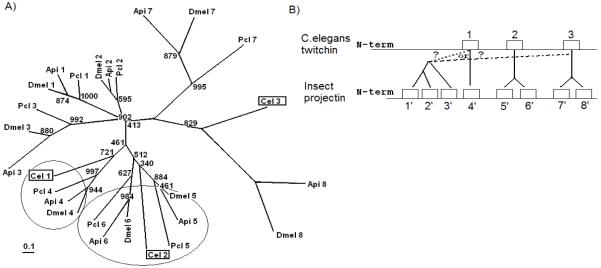

Duplication within the N-8Ig region

The presence of eight Ig domains within the first part of the NH2-terminus of projectin has been reported only within insects. Projectin has been characterized in only one other arthropod, the crayfish (P. clarkii), which was completely derived from cDNA sequencing. Crayfish projectin contains only seven Ig domains (a number that can be further reduced to six by alternative splicing; Oshino et al, 2003). This increase to eight Ig domains appears to have occurred very early in the insect lineage based on preliminary data from analysis of the projectin gene in the silverfish (Apterygote, order: Zygentoma/ Thysanura) (RS; unpublished observation). Maximum parsimony analysis indicates that crayfish Ig1 to Ig7 corresponds to insect Ig1 to Ig7, making the Ig8 in insects the probable result of a duplication event (Figure 4A). The six Ig domains of the N-6Ig region are present in both crayfish and insects, and maximum parsimony analysis indicates that crayfish Ig8 to Ig13 corresponds to insect Ig9 to Ig14 (data not shown). The more ancestral protein, twitchin, in C. elegans only contains a total of nine Ig domains at its NH2-terminus. Both maximum parsimony and maximum likelihood analyses indicate that twitchin Ig4 to Ig9 corresponds to insect Ig9 to Ig14, whereas C. elegans Ig1 clusters with arthropod Ig4, C. elegans Ig2 with arthropod Ig5/6, and C. elegans Ig3 with arthropod Ig7/8 (Figure 4A). This clustering leads to a possible pathway for domain duplications to explain the increase of the first Ig stretch from three domains in C. elegans twitchin to eight in insect projectin (Figure 4B). In such a model, Ig5 and Ig6 would be the product of duplication and divergence from twitchin Ig2. Similarly, Ig7 and Ig8 would be the product of duplication from twitchin Ig3. Interestingly the tree seems to indicate that twitchin Ig3 is more closely related to insect Ig8 than arthropod Ig7. This may suggest that Ig7 diverged more than Ig8 after the duplication event that created the eighth domain in basal insects. The tree also suggests that arthropod Ig1 to Ig3 are the products of two successive duplications from either C. elegans Ig3 or Ig1, the split creating arthropod Ig1 and Ig2 probably being the last one to occur (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Duplication within the N-8Ig region of the projectin protein. A) The first N-Ig domains of C. elegans twitchin (Cel-Ig1-3), P. clarkii (Pcl-Ig1-7), A. pisum (Api1-8) and D. melanogaster (Dmel1-8) projectin were aligned and a phylogenetic tree derived (See M&M for details). The scale bar corresponds to 0.1 estimated amino acid substitutions per site. B) A proposed scenario for N-8Ig domain duplication from three Ig domains in C. elegans to eight in insects based on the current phylogenetic relationship between the individual Ig domains.

Crayfish projectin is known to undergo alternative splicing within the N-7Ig region where the first half of Ig5 can be spliced directly to the second half of Ig6, removing one exon as part of a larger intron and creating a new Ig domain hybrid between Ig5 and Ig6 (Oshimo et al, 2003). Comparison of the splice site positions within the various insect genes reveals that this alternative splicing is still possible in the A. pisum gene as the exon-intron pattern is consistent with the formation of an in-frame hybrid Ig domain by alternative splicing. This possibility is lost, however, in more derived insects, even though the potential for other alternative splicing events still exists within this region.

Conservation within the Ig, FnIII, and kinase domains

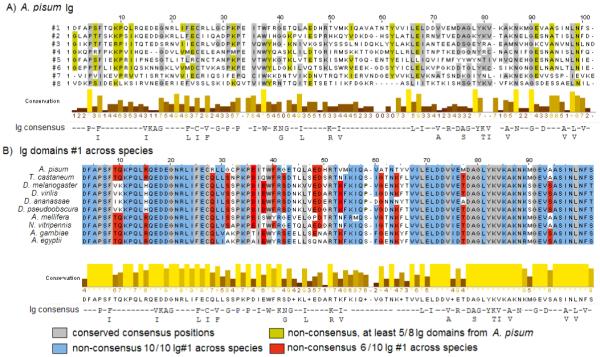

Multiple alignment analysis of FnIII and Ig domains from all the insect species included in this study indicates a very high degree of amino acid conservation across different species between Ig or FnIII domains found at identical positions within the protein, e.g. Ig1 in A. pisum is more similar to Ig1 in D. melanogaster than it is to Ig5 in A. pisum (see Figures 5 and 6). The conserved residues between domains within one species tend to be the ones corresponding to the consensus positions as originally defined for the Ig and FnIII domains of C. elegans twitchin (Benian et al, 1989). Figure 5A represents the alignment of the first eight Ig domains within the N-8Ig region of A. pisum. It shows that, after excluding conserved consensus positions (26, gray positions), only 17 positions out of 98 amino acids are conserved (including conservative substitutions) in at least five of the eight Ig domains (ocher positions in Figure 5A). In Figure 5B, the alignment for Ig1 in all studied insects indicates that, after excluding the consensus positions (23, gray positions), 50 positions out of the total 98 amino acids are conserved (including conservative substitutions) across all 10 insect species (blue positions), and another 16 are shared by 6 out of 10 insect species (red positions).

FIGURE 5.

Jalview of CLUSTAL alignments for the Ig domains of projectin. A) The first 8 Ig domains of the A. pisum protein. B) Ig1 from all available projectin sequences in this study. Conserved amino acids are highlighted with different colors depending on whether or not these amino acids coincide with the conserved positions in the consensus sequence. The Ig consensus sequence used in this study was originally defined for twitchin Ig domain (Benian et al, 1988).

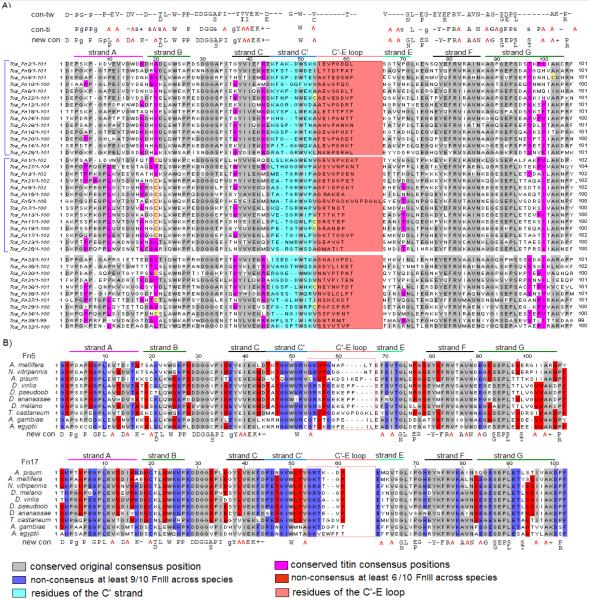

FIGURE 6.

Jalview of CLUSTAL alignments for the FnIII domains of projectin. The relative positions of the A-G strands and the loops forming the FnIII fold were predicted from the alignment with the titin Fn3 fold. A) The 39 FnIII domains of the T. castaneum protein are aligned with the twitchin consensus (con-tw; (Benian et al, 1988)), the titin consensus (con-ti; Amodeo et al, 2001) and the new consensus derived for insect projectin FnIII (new con). The residues comprising the highly variable C’ strand and C’-E loop are highlighted in light blue and light pink respectively. Blue brackets on the side of the alignment are for the odd and even-numbered FnIII domains of the core region. B) Fn5 and Fn17 from all available projectin sequences in this study. Conserved amino acids are highlighted with different colors depending on whether or not these amino acids coincide with the conserved positions in the consensus sequence.

A similar analysis was performed for all 39 FnIII domains within all 10 studied insect species and Figure 6A presents the comparison for T. castaneum as an example. The projectin FnIII domains were modeled manually on the representation of the titin FnIII fold, and the A-G β-sheets are indicated above the alignments in Figure 6 (Amodeo et al, 2001). All 39 FnIII domains in all 10 insects were aligned against both the twitchin consensus (con-tw) and the titin consensus (con-ti) sequences. This alignment generates a slightly different consensus for insect projectin FnIII domains (new con). As described above for the Ig domains, there is an overall higher conservation across species for domains at similar position (red and blue residues in Figure 6B) than between FnIII domains within one species.

The repeated pattern in the core region of projectin is less complex than in titin, consisting of 14 simple [Fn-Fn-Ig] modules representing Fn1-28 (domains within the blue brackets in Figure 6A). The alignment presented in Figure 6A reveals another interesting pattern of conservation specific for that region of the protein. All the even-numbered FnIII domains are missing a residue at position 7. Position 9 is usually a highly conserved proline but only in odd-numbered domains. Position 10 is a proline in even-numbered, but a leucine in odd-numbered domains. Several other residues (for example cysteine at position 20) follow a similar pattern, where the conservation is higher between either odd or even-numbered domains. This pattern does not extend to domains Fn29-39 probably because they belong to the intermediate region of the protein (Figure 1). This analysis holds true within all the analyzed insect projectins.

Two amino acid stretches at the center of the FnIII domains vary in both their length and amino acid sequence among the 39 Fn domains except for the highly conserved tryptophan residue at position 50 (equivalent to W54 in titin Fn3 model, Muhle-Goll et al, 2001) and a hydrophobic residue at position 53. When the projectin fibronectin domains are modeled on the representation of titin Fn3 fold, these two variable clusters correspond to strand C’ (boxed in light blue in Figure 6) and loop C’E (boxed in light pink in Figure 6; Amodeo et al, 2001; Muhle-Goll et al, 2001). Even though the residues in the C’ strand are very different from domain to domain within a species, when the FnIII domains at the same position within the 10 different insects are compared, there is a higher overall conservation of the residues (for example residues highlighted in blue and red in Figure 6B). The C’E loop shows greater length variation (three to nine amino acids) and is less conserved even between domains at the same position within all 10 insects (Figure 6B).

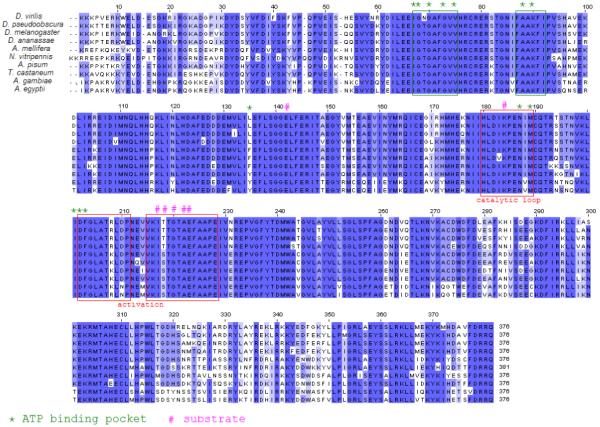

The kinase domain of all 10 insects is extremely conserved as shown in Figure 7, with the conservation including amino acids other than the ones implicated in the different loops and pockets, such as the ATP and substrate binding sites, as well as the catalytic and activation loop (CDD reference # CD00180, Marchler-Bauer et al, 2007). In all species except for the two mosquitoes, the kinase region is encoded by three or more exons (see Supplemental materials 1), leaving no possibility for alternative splicing to either remove or inactivate the kinase activity without actually changing the reading frame for the downstream COOH-terminus of the protein.

FIGURE 7.

Jalview of CLUSTAL alignments for the kinase domains of projectin. Conserved amino acids are highlighted with different shades of blue to represent the degree of conservation. The position of the ATP and substrate binding sites, as well as the catalytic and activation loops were modeled on this sequence by comparison with twitchin kinase and serine-threonine kinase as available in the Conserved Domain Database (CDD v2.13) at NCBI.

Linker Unique sequences

In the N-8Ig-encoding region, the Ig domains are linked by short unique sequences (between 6 and 11 amino acid-long) that can be considered as “extensions” of the Ig domains. In a given species, the amino acid sequences of these various linkers are very different from one another, but they are well conserved between all characterized projectin proteins at a specific location, reminiscent of the pattern described above for the Ig and FnIII domains: higher conservation between species at a given position rather than between domains within one protein. In D. melanogaster and D. virilis, the linker between Ig1 and 2 is actually encoded by two alternatively spliced exons, as demonstrated by RT-PCR analysis (Southgate and Ayme-Southgate, 2001 and data not shown). The presence of two similar alternative exons has also been predicted from the sequence in D. ananassae and D. pseudoobscura, but not verified by RT-PCR. In D. melanogaster the alternative splicing is known to be muscle-type specific, one exon (and therefore one linker) being IFM-specific, whereas the other exon is used in all other synchronous muscles (Southgate and Ayme-Southgate, 2001). The muscle type specificity of the alternative exons has not been confirmed by RT-PCR analysis in the other three Drosophila species. The presence of two alternatively spliced exons between Ig1 and 2 may well be specific to Drosophila sp., as examination of the genomic sequences between Ig1 and 2 in non-Drosophila insects has revealed the presence of only one of these two possible small exons.

In the N-6Ig-encoding region, there is only one such “linker” sequence present between Ig9 and Ig10 (Figure 2). This linker is much longer with 46 amino acids, and well conserved across insect species at both the DNA and amino acid levels (average 72% and 75.8% respectively). We referred to this new unique sequence as the “FRAM” domain based on the 100% conservation of these four specific amino acids across all the studied species. This sequence is also present at the same relative position within crayfish projectin and even in C. elegans twitchin. It is not, however, found in titin, or other proteins as tested using tBLASTn, nor does the “FRAM” sequence match any consensus domain from the Conserved Domain Database (CDD v2.13) at NCBI (data not shown).

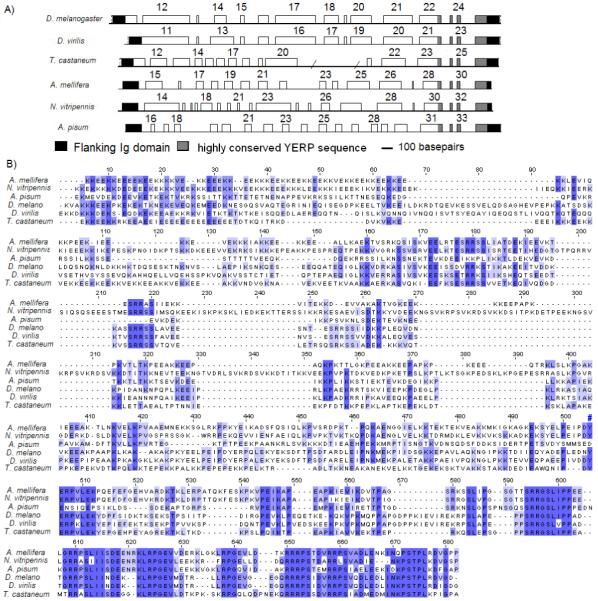

PEVK sequences

The identification of the PEVK region by RT-PCR analysis was completed for T. castaneum, A. mellifera, N. vitripennis, D. virilis, and A. pisum. The data indicate that the length of the region is relatively conserved from 448 (A. pisum) to 655 amino acids (D. melanogaster) (Table 2). Markedly different from the rest of the gene, the PEVK region is assembled from a comparable number of exons in all available insects (between 14 and 17; Table 2); yet the actual size of the exons and introns are not conserved, sometimes even between related species (Figure 8A, Supplemental Materials-1). Pairwise graphical alignments using the Dotlet software (Junier and Pagni, 2000), as well as multiple sequence alignments using CLUSTALW indicate that the amino acid sequences present between Ig8 and Ig9 are highly variable through most of their length, except for a stretch of 140-150 highly conserved amino acids just before Ig9 (Figure 8B). For example, LALIGN alignment between the A. mellifera and D. melanogaster PEVK indicates only a 32.5% identity (Score: 263 E [10,000]: 3.2e-16). We would like to redefine, therefore, the amino acid sequence located between Ig8 and Ig9 as two distinct regions, the PEVK domain per se (thereafter referred to as the PEVK region) and a new unique sequence just before the Ig9 domain that we will refer to as the “YERP” sequence. Part of the “YERP” sequence is also included at the same position within the previously described crayfish EK domain, and in unique sequence #3 of C. elegans twitchin. This “YERP” sequence is not found in any other proteins, including vertebrate titin.

TABLE 2.

PEVK data

This table summarizes the main information for the PEVK domain including its length and exon composition. The percentages of P, E, V, and K amino acids, as well as E and K amino acids are provided for the entire sequence between Ig8 and Ig9 (previously defined PEVK), as well as the two subdomains, the PEVK per se (newly defined PEVK) and the YERP sequence. The C. elegans (Cel) and crayfish (Pcl) data are included for comparison.

| Cel | Pcl | Dmel | Dvir | Tcas | Nvi | Amel | Api | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| length (aa) | 189 | 411 | 655 | 650 | 464 | 618 | 467 | 448 | ||||||||

| exon # | N/A | 15 | 14 | 16 | 15 | 16 | 17 | |||||||||

| PEVK | EK | PEVK | EK | PEVK | EK | PEVK | EK | PEVK | EK | PEVK | EK | PEVK | EK | PEVK | EK | |

| previous PEVK | 34.9 | 23.8 | 54.0 | 39.4 | 42.0 | 27.6 | 42.0 | 26.0 | 54.0 | 39.7 | 52.0 | 38.0 | 58.0 | 44.0 | 45.5 | 32.0 |

| new PEVK | 36.5 | 25.8 | 57.3 | 44.8 | 44.5 | 30.0 | 46.0 | 30.0 | 59.6 | 45.4 | 55.5 | 41.5 | 62.8 | 50.0 | 47.0 | 34.0 |

| YERP region | 26.6 | 13.0 | 38.0 | 22.0 | 28.0 | 10.0 | 28.0 | 10.0 | 29.4 | 14.0 | 27.0 | 11.0 | 31.8 | 11.5 | 39.5 | 23.0 |

FIGURE 8.

A) Schematic representation of the exon-intron pattern in the PEVK genomic regions. Numbers above indicate the exon # from the beginning of the gene. Exons are drawn to scale but not the introns. B) Jalview representation of the CLUSTAL-generated alignments for projectin PEVK domains. Conserved amino acids are highlighted such that the darker the shade of blue, the larger the number of different PEVK domains that share the same amino acid at that particular position. The region can be subdivided into two distinct segments: a non-conserved domain and a newly defined highly conserved sequence, referred to as the “YERP” sequence (indicated by the # sign).

Even though there is no substantial sequence conservation between the PEVK regions of the different studied insects, all revealed an elevated frequency of the amino acids P, E, V and K ranging from 44% (D. melanogaster) to 63% (A. mellifera). In contrast, the percentage of P, E, V and K within the YERP sequence decreases from 39% in A. pisum to a low of 28% in D. melanogaster (Table 2). The PEVK domains found in vertebrate titin and in D. melanogaster Sallimus (D-titin) have on average a higher PEVK content (70% and more), and are also characterized by the presence of repeats, such as the PPAK and polyE repeats in titin (Greaser, 2001; Nagy et al, 2005). In contrast, no PPAK-type repeated pattern has been identified in any of the projectin PEVK domains characterized so far by either LaLign, Dotlet analysis, or by visual observation (data not shown). There is, however, a polyE stretch present at the very beginning of the projectin PEVK region in both T. castaneum and the two hymenopteran projectins.

Discussion

Projectin is unique among muscle proteins in several aspects, including its dual location within the sarcomere of different muscle types (i.e. synchronous and asynchronous) and its proposed functions as both a scaffold for myofibril assembly and as an elastic protein in stretch activation. Our evolutionary analysis of projectin provided important insights into how separate regions of the protein may have been modified under different evolutionary constraints.

The observed amplification in the number of NH2-Ig domains from three in nematode twitchin to seven (or eight) in arthropods could account for the apparent extension of the NH2-terminal part of the molecule into the I band region. This would allow for its anchoring at the Z band while still maintaining its association to myosin within the A band. Both nematode twitchin and crayfish projectin have been shown to be localized to the A bands of oblique sarcomeres and giant sarcomeres of the claw and flexor muscles respectively (Hu et al., 1990; Manabe et al., 1993, Oshino et al., 2003). The study by Oshino revealed, however, that a part of the NH2-terminal region of crayfish projectin does extrude into the I band, but does not physically reach the Z band in both the closer and flexor sarcomeres (Oshino et al, 2003). In many different insects that use asynchronous muscles (Bullard et al, 1977; Lakey et al, 1990; Vigoreaux et al, 1991; Nave et al, 1991; AAS unpublished observation) projectin shows an unambiguous dual localization, maintaining the “ancestral” A band position in synchronous muscles, but shifting to include a Z-I band position in asynchronous flight muscles. In insect asynchronous muscles, the current model for C-filament structure proposes that projectin and its companion protein kettin/Sls are physically anchored to the Z-bands through their NH2-terminal regions and overlap with at least part of the A band (Ayme-Southgate et al, 2005; Bullard et al, 2006). The combination of the shorter I band of insect indirect flight muscles and the longer NH2-terminal Ig regions would conceivably allow projectin to be long enough both to be anchored at the Z band while maintaining its association with the myosin filaments.

It is of interest that all the Drosophila species included in this study, and D. melanogaster, possess a small alternatively spliced exon corresponding to a short N-terminal extension of Ig2, with one of these alternative extensions being asynchronous specific in D. melanogaster. Numerous studies using several titin Ig domains have described the direct effect of terminal extensions on the stability of the Ig fold (Politou et al, 1994; Pfuhl et al, 1997). In the case of one titin domain, two constructs differing only in the length of their N-terminal extensions show noticeable differences as the longer NH2-terminus are typically more stable (Politou et al, 1994). The significance of an alternative N-terminal extension for projectin Ig2 is intriguing in relation to any interactions with other proteins during its anchoring to the Z band, and/or a change in the stability between different muscle isoforms. This hypothesis will require further studies.

When the 39 copies of either the Ig or FnIII domains from one species are compared amongst themselves, the conserved residues tend to correspond almost exclusively to the consensus positions. This is consistent with maintaining amino acids essential for the fold of the domain (Bork et al, 1994; Pfuhl and Pastore, 1995; Politou et al, 1995; Fong et al, 1996; Kenny et al, 1999). On the other hand, there is a higher level of conservation among Ig and FnIII domains found at identical positions within the projectin proteins in different insect species, mainly within the central portion of both domains. NMR and crystallography studies of both domains from twitchin and titin indicate that these residues are found on the surface of both the Ig and FnIII folds and are more likely to participate in position-specific protein interactions (Fong et al, 1996; Pfuhl and Pastore, 1995; Politou et al, 1995; Fraternali and Pastore, 1999; Amodeo et al, 2001; Muhle-Goll et al, 2001; Lee et al, 2007). Assuming that projectin Ig and FnIII domains are folded in a fashion similar to their titin counterparts, the conservation of these surface residues in domains at equivalent positions may actually reflect the likely involvement of specific Ig or FnIII domains in different protein-protein interactions.

The analysis of the gene structure presented in this study supports the observed trend of extensive intron losses that occurred during insect evolution. Within that general trend, the Apis gene is unusual with 95 introns compared to only 70 in the other hymenopteran Nasonia gene. Most of these additional Apis introns are found within the core region of the gene where most of the intron losses have otherwise occurred in the other projectin genes. Because the positions of these additional introns in the Apis sequence are conserved from the more basal aphid gene, it is likely that this represents a lack of intron losses rather that the gain of new introns. A similar observation reporting the lack of intron loss has been described for the family of odorant receptor genes in the honeybee (Foret and Maleszka, 2006).

Even with only 70 introns, the Nasonia projectin gene is still more ancestral in its gene structure than the coleopteran and dipteran projectin genes. Our phylogenetic analysis provides further evidence that the Hymenoptera are the most basal group of the Holometabola, and that they diverged from the Diptera significantly before the Coleoptera. Our study is consistent with findings from morphological data (Kukalová-Peck and Lawrence 2004), as well as sequence analysis of ESTs (Savard et al. 2006), genomic sequences (Zdobnov and Bork 2007), and intron evolution (Krauss et al, 2008).

The region between insect Ig8 and 9 was described in D. melanogaster as the equivalent of titin PEVK domain because of its 50% content in the relevant four amino acids. The current study indicates that the projectin PEVK domains are highly variable within most of their sequence, except for a conserved C-terminal segment (termed the YERP sequence). The projectin PEVK, however, shows conservation in length and unusual amino acid composition. Multiple studies of various titin PEVK regions indicate that no conventional secondary structures such as α-helix or β-sheet are evident in titin PEVK sequences (Greaser et al, 2000). Instead, the titin PEVK domain is thought to be in an open, flexible conformation with stable structural folds consisting of Polyproline (PPII) left-handed helices (Gutierez-Cruz et al, 2001; Li et al, 2001; Ma and Wang, 2003). Electrostatic interactions between positively and negatively charged residues could also contribute to different coexisting configurations arising upon stretching and release (Forbes et al 2005). Other authors, however, did not detect PPII helices in other regions of titin PEVK and have classified the PEVK modules as intrinsically disordered proteins (IDP) (Duan et al, 2006). Whether various examples of the projectin PEVK domains contain PPII helices and whether they resemble IDPs remain to be investigated. It is a tentative idea that comparable mechanical properties could be accomplished by PEVK domains with very divergent amino acid sequences, by maintaining features, such as an unusually high P, E, V, and K content, potential charge interactions, and the possibility to generate PPII-like helices. A recent study by Daughdrill et al (2007) of RPA70 (Replication protein A) and an “intrinsically unstructured linker domain” found between two of its globular domains supports the possibility of conservation of dynamic behavior (and potentially molecular function) in the apparent absence of amino acid conservation. As further support for this idea, a study by Granzier et al has shown that the titin PEVK domain of chicken is significantly different in length, sequence and PEVK content as compared to mammalian PEVK titin, yet is expected to accomplish essentially similar molecular functions (Granzier et al, 2007).

The reported analysis of projectin provides new insight into how different regions of the protein may have evolved over time. For the Ig and FnIII domains, the evolutionary constraints on the domain sequences are linked to the maintenance of their specific three-dimensional conformation in order to preserve both the functional folds and potential protein-protein interactions. On the other hand, the PEVK region must maintain features such as length and unusual amino acid composition, but without any strict amino acid sequence conservation. Continued analysis to expand our projectin data to other insect groups, including more basal lineages, may help refine this evolutionary analysis to further understand the conservation as well as the changes within the projectin protein in relation to its dual functions, dual localizations, and the modifications of insect flight physiology during evolution.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health grant # 1R15AR053137-01 to AAS. This publication was also made possible by NIH Grant Number P20 RR-016461 from the National Center for Research Resources. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. We want to thank Dr. J. Evans (USDA, Beltsville, MD), Dr. S. Brown (Kansas State University, KS), Dr. J. Werren (University of Rochester, NY), Dr. D. Stern (Princeton U., NJ), and the Tucson Drosophila stock center for providing the live insects. We also want to acknowledge the Human Genome Sequencing Center at Baylor College of Medicine for making accessible the genome sequencing data for Tribolium castaneum, Nasonia vitripennis, and Acyrthosiphon pisum before publication.

Bibliography

- Abascal F, Zardoya R, Posada D. ProtTest: Selection of bestfit models of protein evolution. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:2104–2105. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abascal F, Posada D, Zardoya R. MtArt: a new model of amino acid replacement for Arthropoda. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1–5. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Meyers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amodeo P, Fraternali F, Lesk AM, Pastore A. Modularity and homology: modeling of the titin type I modules and their interfaces. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;311:283–296. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayme-Southgate A, Vigoreaux JO, Benian GM, Pardue ML. Drosophila has a twitchin/titin-related gene that appears to encode projectin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1991;88:7973–7977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.18.7973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayme-Southgate A, Southgate R, Saide J, Benian G, Pardue ML. Both synchronous and asynchronous muscle isoforms of projectin (the Drosophila bent locus product) contain functional kinase domains. J. Cell Biol. 1995;128:393–403. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.3.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayme-Southgate A, Southgate R, Kulp McEliece M. In: Pollack GH, Granzier H, editors. Drosophila projectin: a look at protein structure and sarcomeric assembly; Proceedings: Elastic Filaments of the Cell; Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ayme-Southgate A, Saide J, Southgate R, Bounaix C, Camarato A, Patel S, Wussler C. In indirect flight muscles Drosophila projectin has a short PEVK domain, and its NH2-terminus is embedded at the Z-band. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 2005;26:467–477. doi: 10.1007/s10974-005-9031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benian GM, Kiff JE, Neckelmann N, Moerman DG, Waterston RH. Sequence of an unusually large protein implicated in regulation of myosin activity in C. elegans. Nature. 1989;342:45–50. doi: 10.1038/342045a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benian GM, L’Hernault SW, Morris ME. Additional sequence complexity in the muscle gene, unc-22, and its encoded protein, twitchin, of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1993;134:1097–1104. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.4.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutel RG, Pohl H. Endopterygote systematics-where do we stand and what is the goal (Hexapoda, arthropoda): REVIEW Syst. Entomology. 2006;31:202–219. [Google Scholar]

- Bork P, Holm L, Sander C. The Immunoglobulin fold: structural classification, sequence patterns and common core. J. Mol. Biol. 1994;242:309–320. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullard B, Hammond KS, Luke BM. The site of paramyosin in insect flight muscle and the presence of an unidentified protein between myosin filaments and Z-line. J Mol Biol. 1977;115:417–40. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90163-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullard B, Bell J, Craig R, Leonard K. Arthrin: a new actin-like protein in insect flight muscle. J. Mol. Biol. 1985;182:443–454. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90203-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullard B, Goulding D, Ferguson C, Leonard K. In: Pollack GH, Granzier H, editors. Links in the chain: the contribution of kettin to the elasticity of insect muscles; Proceedings: Elastic Filaments of the Cell; Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bullard B, Burkart C, Labeit S, Leonard K. The function of elastic proteins in the oscillatory contractions of insect flight muscle. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 2005;26:479–485. doi: 10.1007/s10974-005-9032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullard B, Garcia T, Benes V, Leake M, Linke W, Oberhauser A. The molecular elasticity of the insect flight muscle proteins projectin and kettin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:4451–4456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509016103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne MB, Edwards KA, Erickson HP, Kiehart DP. Drosophila stretchin-MLCK is a novel member of the Titin/Myosin light chain kinase family. J Mol Biol. 2000;300:759–77. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley JK, Southgate R, Ayme-Southgate A. Structure of the Drosophila projectin protein: isoforms and implication for projectin filament assembly. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;279:201–210. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughdrill GW, Narayanaswami P, Gilmore SH, Belczyk A, Brown CJ. Dynamic behavior of an intrinsically unstructured linker domain is conserved in the face of negligible amino acid sequence conservation. J Mol Evol. 2007;65:277–288. doi: 10.1007/s00239-007-9011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimmic MW, Rest JS, Mindell DP, Goldstein RA. rtREV: an amino acid substitution matrix for inference of retrovirus and reverse transcriptase phylogeny. J Mol Evol. 2002;55:65–73. doi: 10.1007/s00239-001-2304-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duana Y, DeKeysera JG, Damodaran S, Greaser ML. Studies on titin PEVK peptides and their interaction. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2006;454(1):16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. PHYLIP: Phylogeny inference package (version 3.2) Cladistics. 1989;5:164–166. [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. Inferring phylogeny from protein sequences by parsimony, distance and likelihood methods. Methods Enzymol. 1996;266:368–382. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)66026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong S, Hamill SJ, Proctor M, Freund SMV, Benian GM, Chothia C, Bycroft M, Clarke J. Structure and stability of an immunoglobulin domain from twitchin, a muscle protein of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;264:624–639. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes JG, Jin AJ, Ma W, Guttierez-Cruz G, Tsai WL, Wang K. Titin PEVK segment: charge driven elasticity of the open and flexible polyampholyte. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 2005;26:291–301. doi: 10.1007/s10974-005-9035-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foret S, Maleszka R. Function and evolution of a gene family encoding odorant binding-like proteins in a social insect, the honey bee (Apis mellifera) Genome Res. 2006;16(11):1404–13. doi: 10.1101/gr.5075706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraternali F, Pastore A. Modularity and homology: modeling of the type II module family from titin. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;290:581–593. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freiburg A, Trombitás K, Hell W, Cazorla O, Fougerousse F, Centner T, Kolmerer B, Witt C, Beckmann JS, Gregorio CC, Granzier H, Labeit S. Series of exon-skipping events in the elastic spring region of titin as the structural basis for myofibrillar elastic diversity. Circ. Res. 2000;86:1114–1121. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.11.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda N, Granzier HL. Titin/connectin-based modulation of the Frank-Starling mechanism of the heart. J Musc. Res. Cell Motil. 2005;26:319–323. doi: 10.1007/s10974-005-9038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyrberg CC, Labeit S, Bullard B, Leonard K, Fyrberg EA. Drosophila projectin: relatedness to titin and twitchin and correlation with lethal (4) 102CDa and bent-dominant mutants. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 1992;249:33–40. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1992.0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautel M. The super-repeats of titin/connectin and their interactions: glimpses at sarcomeric assembly. Adv. Biophys. 1996;33:27–37. doi: 10.1016/s0065-227x(96)90020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granzier HL, Wang K. Passive tension and stiffness of vertebrate skeletal and insect flight muscles: the contribution of weak cross-bridges and elastic filaments. Biophys J. 1993;65:2141–2159. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81262-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granzier H, Helmes M, Cazorla O, McNabb M, Labeit D, Wu Y, Yamasaki R, Redkar A, Kellermeyer M, Labeit S, Trombitas K. In: Pollack GH, Granzier H, editors. Mechanical properties of titin isoforms; Proceedings: Elastic Filaments of the Cell; Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. 2000; pp. 283–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granzier HL, Labeit S. The giant protein titin: a major player in myocardial mechanics, signaling, and disease. Circ Res. 2004;94:284–295. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000117769.88862.F8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granzier H, Radke M, Royal J, Wu Y, Irving TC, Gotthardt M, Labeit S. Functional genomics of chicken, mouse and human titin supports splice diversity as an important mechanism for regulating biomechanics of striated muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp Physiol. 2007;293:557–567. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00001.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaser ML, Wang S-M, Berri M, Mozdziak PE, Kumazawa Y. In: Pollack GH, Granzier H, editors. Sequence and mechanical implications of cardiac PEVK; Proceedings: Elastic Filaments of the Cell; Kluwer Academic/ Plenum Publishers. 2000.pp. 53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Greaser ML. Identification of new repeating motifs in titin. Proteins. 2001;43:145–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0134(20010501)43:2<145::aid-prot1026>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S, Gascuel O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Systematic Biology. 2003;52(5):696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S, Lethiec F, Duroux P, Gascuel O. PHYML Online--a web server for fast maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic inference. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W557–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki352. Web Server issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierez-Cruz G, van Heerden A, Wang K. Modular motifs, structural folds and affinity profiles of PEVK segments of human fetal skeletal muscle titin. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:7442–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008851200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakeda S, Endo S, Saigo K. requirements of kettin, a giant muscle protein highly conserved in overall structure in evolution, for normal muscle function, viability and flight activity of Drosophila. J. Cell Biol. 2000;148:101–114. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu DH, Matsuno A, Terakado K, Matsuura T, Kimura S, Maruyama K. Projectin is an Invertebrate Connectin (Titin): Isolation from crayfish claw muscle and localization in crayfish claw muscle and insect flight muscle. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 1990;11:497–511. doi: 10.1007/BF01745217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Miller W. A time-efficient, linear-space local similarity algorithm. Adv. Appl. Math. 1991;12:337–357. [Google Scholar]

- Jones DT, Taylor WR, Thornton JM. The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comp. Appl. Biosci. 1992;8:275–282. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/8.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephson RK, Malamud JG, Stokes DR. Asynchronous Muscles: A Primer. J. Exp. Biol. 2000;203:2713–2722. doi: 10.1242/jeb.203.18.2713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junier T, Pagni M. Dotlet: diagonal plots in a web browser. Bioinformatics. 2000;2:178–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny PA, Liston EM, Higgins DG. Molecular evolution of immunoglobulin and fibronectin domains in titin and related muscle proteins. Gene. 1999;232(1):11–23. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00122-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolmerer B, Clayton J, Benes V, Allen T, Ferguson C, Leonard K, Weber U, Knekt M, Ansorge W, Labeit S, Bullard B. Sequence and expression of the kettin gene in Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;296:435–448. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauss V, Thümmler C, Georgi F, Lehmann J, Stadler PF, Eisenhardt C. Near intron positions are reliable phylogenetic markers: An application to Holometabolous Insects. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25(5):821–30. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn013. Epub 2008 Feb 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulke M, Neagoe C, Kolmerer B, Minajeva A, Hinssen H, Bullard B, Linke WA. Kettin, a major source of myofibrillar stiffness in Drosophila indirect flight muscle. J. Cell Biol. 2001;154:1045–1057. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200104016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukalová-Peck J, Lawrence JF. Relationship among Coleopteran suborders and major Endoneopteran lineages: Evidence from hind wing characters. Eur. J. Entomol. 2004;101:95–144. [Google Scholar]

- Lakey A, Ferguson C, Labeit S, Reedy M, Larkins A, Butcher G, Leonard K, Bullard B. Identification and localization of high molecular weight proteins in insect flight and leg muscles. EMBO J. 1990;9:3459–3467. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07554.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EH, Hsin J, Mayans O, Schulten K. Secondary and tertiary structure elasticity of titin Z1Z2 and a titin chain model. Biophys. J. 2007;93(5):1719–35. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.105528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Oberhauser AF, Redick SD, Carrion-Vazquez C, Erickson HP, Fernandez JM. Multiple conformations of PEVK proteins detected by single-molecule techniques. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2001;98:10682–10686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191189098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linke WA, Rudy DE, Centner T, Gautel M, Witt CC, Labeit S, Gregorio CC. I-band titin in cardiac muscle is a three-element molecular spring and is critical for maintaining thin filament structure. J. Cell Biol. 1999;246:631–644. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.3.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma K, Wang K. Malleable conformation of the elastic PEVK segment of titin: non-cooperative interconversions of polyproline II helix, beta turn and unordered structures. Biochem. J. 2003;374:687–695. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manabe T, Kawamura Y, Higuchi H, Kimura S, Maruyama K. Connectin, giant elastic protein, in giant sarcomeres of crayfish claw muscle. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1993;14(6):654–65. doi: 10.1007/BF00141562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchler-Bauer A, Anderson JB, Derbyshire MK, DeWeese-Scott C, Gonzales NR, Gwadz M, Hao L, He S, Hurwitz DI, Jackson JD, Ke Z, Krylov D, Lanczycki CJ, Liebert CA, Liu C, Lu F, Lu S, Marchler GH, Mullokandov M, Song JS, Thanki N, Yamashita RA, Yin JJ, Zhang D, Bryant SH. CDD: a conserved domain database for interactive domain family analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D237–40. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JR, Vigoreaux JO, Maughan DW. The Drosophila projectin mutant, bentD, has reduced stretch activation and altered flight muscle kinetics. J. Muscle. Res. Cell Motil. 1999;20:797–806. doi: 10.1023/a:1005607818302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JR. Stretch activation: towards a molecular mechanism. In: Vigoreaux J, editor. Nature’s Versatile Engine: Insect Flight Muscle Inside and Out. Landes Bioscience, Springer NY Publishers; 2006. pp. 44–60. [Google Scholar]

- Muhle-Goll C, Habeck M, Cazorla O, Nilges M, Labeit S, Granzier H. Structural and functional studies of titin’s Fn3 modules reveal conserved surface patterns and binding to myosin S1 — a possible role in the Frank-Starling mechanism of the heart. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;313:431–447. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy A, Grama L, Huber T, Bianco P, Trombitas K, Granzier HL, Kellermayer SZ. Hierarchical extensibility in the PEVK domain of skeletal-muscle titin. Biophys. J. 2005;89:329–336. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.057737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nave R, Weber K. A myofibrillar protein of insect muscle related to vertebrate titin connects Z band and A band: purification and molecular characterization of invertebrate mini-titin. J. Cell Sci. 1990;95:535–544. doi: 10.1242/jcs.95.4.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nave R, Fürst D, Vinkemeier U, Weber K. Purification and physical properties of nematode mini-titins and their relation to twitchin. J Cell Sci. 1991;98:491–6. doi: 10.1242/jcs.98.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshino T, Shimamura J, Fukuzawa A, Maruyama K, Kimura S. The entire cDNA sequences of projectin isoforms of crayfish claw closer and flexor muscles and their localization. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2003;24(7):431–438. doi: 10.1023/a:1027313204786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page RDM. TREEVIEW: An application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Computer Applications in the Biosciences. 1996;12:357–358. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfuhl M, Pastore A. Tertiary structure of an immunoglobulin-like domain from the giant muscle protein titin: a new member of the I set. Curr. Biol. 1995;3:391–401. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfuhl M, Improta S, Politou AS, Pastore A. when a module is also a domain: the role of the N-Terminus in the stability and the dynamics of immunoglobulin domains from titin. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;265:242–256. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Politou AS, Gautel M, Pastore CJA. Immunoglobulin-type domains of titin are stabilized by amino-terminal extension. FEBS lett. 1994;352:27–31. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00911-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Politou AS, Thomas DL, Pastore A. The folding and stability of titin immunoglobulin-like modules, with implications for the mechanism of elasticity. Biophys. J. 1995;69:2601–2610. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80131-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle JWS. The excitation and contraction of the flight muscles of insects. J. Physiol. Lond. 1949;108:226–232. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1949.sp004326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle JWS. Stretch activation of muscle: function and mechanism. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 1978;201:107–130. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1978.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle JWS. The Bidder lecture, 1980: The evolution of fibrillar muscle in insects. J. Exp. Biol. 1981;94:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu F, Lakey A, Agianian B, Hutchings A, Butcher GW, Labeit S, Leonard K, Bullard B. Troponin C in different insect muscle types: identification of two isoforms in Lethocerus, Drosophila and Anopheles that are specific to asynchronous flight muscle in the adult insect. Biochem. J. 2003;371:811–821. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saide JD, Chin-Bow S, Hogan-Sheldon J, Busquets-Turner L, Vigoreaux JO, Valgeirsdottir K, Pardue ML. Characterization of components of Z-bands in the fibrillar flight muscle of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Cell Biol. 1989;109:2157–2167. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.5.2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savard J, Tautz D, Richards S, Weinstock GM, Gibbs RA, Werren JH, Tettelin H, Lercher MJ. Phylogenomic analysis reveals bees and wasps (Hymenoptera) at the base of the radiation of Holometabolous insects. Gen. Res. 2006;16:1334–1338. doi: 10.1101/gr.5204306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz S, Schankin CJ, Prinz H, Curwen RS, Ashton PD, Caves LSD, Fink RHA, Sparrow JC, Mayhew P, Veigel C. Molecular evolutionary convergence of the flight muscle protein arthrin in Diptera and Hemiptera. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2003;20(12):2019–2033. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southgate R, Ayme-Southgate A. Drosophila projectin contains a spring-like PEVK region, which is alternatively spliced. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;313:1037–1045. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL X windows interface: Flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trombitas K. In: Pollack GH, Granzier H, editors. Connecting filaments: a historical prospective; Proceedings: Elastic Filaments of the Cell; Kluwer Academic/ Plenum Publishers. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Vigoreaux JO, Saide JD, Pardue ML. Structurally different Drosophila striated muscles utilize distinct variants of Z-band associated proteins. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 1991;12:340–354. doi: 10.1007/BF01738589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigoreaux JO, Moore JR, Maughan DW. In: Pollack GH, Granzier H, editors. Role of the elastic protein projectin in stretch activation and work output of Drosophila flight muscles; Proceedings: Elastic Filaments of the Cell; Kluwer Academic/ Plenum Publishers. 2000; pp. 237–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler WC, Whiting M, Wheeler QD, Carpenter JM. The phylogeny of the extant hexapod orders. Cladistics. 2001;17:113–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2001.tb00115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan S, Goldman N. A general empirical model of protein evolution derived from multiple protein families using a maximum-likelihood approach. Mol Biol Evol. 2001;18:691–699. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zdobnov EM, Bork P. Quantification of insect genome divergence. Trends in Genet. 2007;23:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.