Abstract

Objective

To assess the impact on mortality related to pregnancy of supplementing women of reproductive age each week with a recommended dietary allowance of vitamin A, either preformed or as β carotene.

Design

Double blind, cluster randomised, placebo controlled field trial.

Setting

Rural southeast central plains of Nepal (Sarlahi district).

Subjects

44 646 married women, of whom 20 119 became pregnant 22 189 times.

Intervention

270 wards randomised to 3 groups of 90 each for women to receive weekly a single oral supplement of placebo, vitamin A (7000 μg retinol equivalents) or β carotene (42 mg, or 7000 μg retinol equivalents) for over 3½ years.

Main outcome measures

All cause mortality in women during pregnancy up to 12 weeks post partum (pregnancy related mortality) and mortality during pregnancy to 6 weeks postpartum, excluding deaths apparently related to injury (maternal mortality).

Results

Mortality related to pregnancy in the placebo, vitamin A, and β carotene groups was 704, 426, and 361 deaths per 100 000 pregnancies, yielding relative risks (95% confidence intervals) of 0.60 (0.37 to 0.97) and 0.51 (0.30 to 0.86). This represented reductions of 40% (P<0.04) and 49% (P<0.01) among those who received vitamin A and β carotene. Combined, vitamin A or β carotene lowered mortality by 44% (0.56 (0.37 to 0.84), P<0.005) and reduced the maternal mortality ratio from 645 to 385 deaths per 100 000 live births, or by 40% (P<0.02). Differences in cause of death could not be reliably distinguished between supplemented and placebo groups.

Conclusion

Supplementation of women with either vitamin A or β carotene at recommended dietary amounts during childbearing years can lower mortality related to pregnancy in rural, undernourished populations of south Asia.

Key messages

Maternal vitamin A deficiency, evident as night blindness or low serum retinol concentration during pregnancy, is widely prevalent in rural south Asia

In Nepal, women of reproductive age who were given 7000 μg retinol equivalents of vitamin A on a weekly basis showed a reduction in mortality related to pregnancy of 40%

Weekly dosing with 42 mg β carotene (also providing 7000 μg retinol equivalents) lowered their mortality by 49%

Preventing maternal vitamin A deficiency in rural South Asia can lower the risk of mortality of women during and after pregnancy

Introduction

Vitamin A deficiency is common among women in developing countries. Mean serum retinol concentrations of about 1.05 μmol/l (300 μg/l) have been reported during pregnancy among diverse groups of south Asian women1–6 in comparison with values of 1.57-1.75 μmol/l (450-500 μg/l) in better nourished populations.7

Concern about maternal vitamin A deficiency has focused on its effects on fetal and infant vitamin A status,1,8–10 health, and survival,8,11 with little attention being paid to its effects on the health consequences for the woman. An early trial in England reported that maternal vitamin A supplementation in late pregnancy through the first week post partum could reduce the incidence of puerperal sepsis,12 but this lead was ignored. In Nepal maternal night blindness, an indicator of vitamin A deficiency,13 has been associated with increased risks of urinary or reproductive tract infections and diarrhoea or dysentery14 and raised acute phase protein concentrations during infection.15 That vitamin A deficiency could predispose women to increased infectious morbidity and mortality is supported by evidence in children and animals.8 Mechanisms underlying such an effect could include impaired barrier defences of epithelial tissues and compromised innate and acquired immunity.8,16

We conducted a study in rural Nepal to assess whether routine supplementation of women with normal, dietary amounts of vitamin A or provitamin A β carotene could favourably affect fetal, infant, or maternal health and survival. In this paper we examine the effects of supplementation on maternal all cause mortality.

Participants and methods

Protocol

The study was a double blind, placebo controlled, cluster randomised trial carried out in Sarlahi district, in the southern plains of Nepal, to assess the effects of continuous, weekly, low dose supplementation of vitamin A or provitamin A β carotene on mortality related to pregnancy in women of reproductive age. The trial required that the two supplementation groups (vitamin A or β carotene) enrol a combined total of around 14 000 pregnancies (roughly 7000 in each group) and the placebo group around 7000 pregnancies, yielding an assignment ratio of 2 to 1, to show a ⩾40% reduction in mortality related to pregnancy with ⩾80% power (1−β) and 95% confidence (1−α). These assumptions were based on an estimated mortality from pregnancy of >600 deaths per 100 000 pregnancies in the study area. Smaller differences (⩾20%) in fetal and infant mortality up to 6 months of age would be discernible with the same sample size.

A total of 270 wards in 30 subdistricts (9 wards each) covering an area of around 500 sq km with a total population of around 176 000 participated in the study. At a local crude birth rate of 41 per 1000 population per year, we anticipated that recruiting 21 000 pregnancies would take around 3 years. The purpose of the trial was explained at community meetings, and written consent to participate was obtained from subdistrict leaders during the year before the start of the trial. Women of childbearing age who were married and living with their husbands as of the first week of March 1994 were recruited to the trial after giving their verbal consent. Newly married women were recruited throughout the trial. Women who were already married who had moved into study wards were not eligible to participate to minimise crossover.

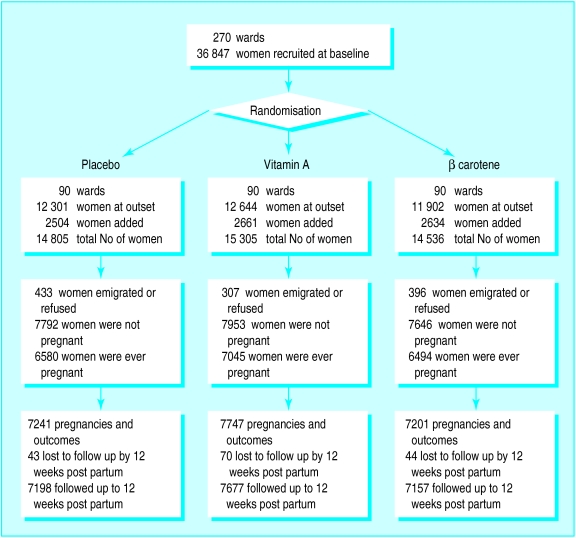

All wards were assigned in Kathmandu by a random draw of numbered chits, blocked on subdistrict, for eligible women to receive one of three identical coded supplements. These were opaque, gelatinous capsules containing peanut oil and 23 300 IU of preformed vitamin A (7000 μg retinol equivalents) as retinyl palmitate, 42 mg of all trans β carotene (7000 μg retinol equivalents, assuming a conversion ratio to retinol of 6 to 1 after uptake17), or no vitamin A or β carotene (placebo) (fig 1). The dosage was intended to deliver an approximate recommended dietary allowance during pregnancy and lactation17 on a weekly basis. All capsules also contained about 5 mg dl-α-tocopherol as an antioxidant.

Figure 1.

Study design with details of follow up

Field procedures

From April 1994 to September 1997 a staff of 432 local female workers carried out weekly home visits and dosed participating women with their assigned supplement. At least 4 days between doses were maintained to avoid any potential risk of toxicity from receiving supplements on two consecutive days. Workers recorded the survival of the women, receipt of capsules, menstrual activity in the previous week, and pregnancy status as reported by women. They revisited the homes of women who were absent until they were able to give them the dose or until the last day of a dosing week. Capsules were not left at homes.

Five months after supplementation and reporting were running smoothly, newly enrolled pregnant women entered into a protocol that included a mid-pregnancy, home based, 7 day dietary, morbidity, and activity assessment and measurement of arm circumference by one of a trained team of about 30 interviewers. Severely ill women were referred to one of seven local health centres for evaluation. A second visit during the third trimester included socioeconomic evaluation. Seven months after the start of the study newly enrolled pregnant women from a subsample of three contiguous subdistricts (27 wards), selected for access, were enrolled for additional measures that required blood collection and measurement of concentrations of retinol and β carotene.

A history of events and illnesses preceding death was obtained by interviewing family members of the dead woman (so called verbal autopsy), usually within one month after the death had been reported. These data were reviewed and a “proximate” cause of death assigned by two doctors (SKK and SMD), one of whom was an obstetrician-gynaecologist; both were blind to treatment allocation. Differences in assignment were discussed until the reviewers agreed on a cause of death.

Analysis

Comparability of randomised groups by socioeconomic and dietary characteristics of women during their first enrolled pregnancy was assessed by the χ2 test; differences in distributions of serum retinol and β carotene concentrations were tested by analysis of variance and comparing the two groups with the t test. We checked compliance in each supplement group by examining the percentage of all eligible doses during the trial (or until death) taken by women and the differences in serum retinol and β carotene concentrations by code among pregnant women in the substudy sample.

Ascertained pregnancies served as the denominator for rate estimation, of which around 91% ended in one or more live births and 6-7% as a declared miscarriage or stillbirth in each group. The remaining 2% of pregnancies had been reported by women at six or more weekly visits but had no reported outcome. We considered these pregnancies to have ended in loss. Pregnancies declared for shorter periods for which no outcome was recorded were considered false positive reports and excluded from the analysis. Eligible pregnancies for this mortality analysis were those ending from mid-July 1994 (by which time women had been routinely given supplements for ⩾5 months) and the end of June 1997, which permitted 12 weeks of postpartum dosing and follow up.

Mortality was evaluated on an intention to treat basis—that is, by supplement assignment irrespective of compliance. Mortality related to pregnancy and specific causes for each group was calculated from deaths that occurred during pregnancy up to 12 weeks post partum and was expressed per 100 000 pregnancies. We extended postpartum follow up from 6 to 12 weeks because maternal mortality related to malnutrition could extend beyond the conventional period of 6 weeks. However, we also examined impact on the maternal mortality ratio (for which we excluded deaths due to reported injury and all deaths >6 weeks post partum) in relation to live births. Relative risks with 95% confidence intervals were calculated with the placebo group as the reference.18 Each confidence interval was adjusted to account for the fact that the ward rather than the person was the unit of randomisation. A quasi-likelihood Poisson regression model was used to estimate the degree of overdispersion in the ward specific death rates.19,20 This overdispersion, due to the design effect, of about 21% of the variance resulted in a 10% inflation in the length of a confidence interval which was applied to the natural logarithm of all estimates of relative risk.

Ethical review

The trial protocol was reviewed and approved by the Nepal Health Research Council in Kathmandu, the Joint Committee on Clinical Investigation at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, and the Teratology Society in Bethesda. Two data and safety monitoring committees approved the trial, one in Baltimore and the other in Kathmandu.

Results

A total of 44 646 women were recruited, 36 847 at the outset and 7799 newly married women during the trial (fig 1). In all, 1136 (2.5%) women were excluded because they emigrated before becoming pregnant or dying or because they declined to be recruited. Overall, 20 119 (45%) women were pregnant 22 189 times. Maternal survival was known after all pregnancy outcomes, but 157 women were lost to follow up during the postpartum period (their median follow up time post partum was around 2 weeks in each group). As the women lost to follow up had completed pregnancies they were included in the denominators for estimating mortality.

At the time of their first study pregnancy, the three groups of women were comparable in age, arm circumference, and weekly dietary intakes. Small differences were evident with respect to cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, and literacy. A smaller percentage of the placebo group were of low Hindu caste or were not Hindus. Only 3% of pregnancies were delivered at a health post, clinic, or hospital (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of mothers during their first study pregnancy by supplement group. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristic | Placebo | Vitamin A | β carotene |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| No of women | 5249 | 5685 | 5266 |

| <20 | 1176 (22.4) | 1268 (22.3) | 1227 (23.3) |

| 20-29 | 3249 (61.9) | 3456 (60.8) | 3081 (58.5) |

| ⩾30 | 824 (15.7) | 961 (16.9) | 958 (18.2) |

| Arm circumference | |||

| No of women | 4639 | 5053 | 4663 |

| <21.5 cm | 2538 (54.7) | 2759 (54.6) | 2513 (53.9) |

| Diet | |||

| No of women | 4702 | 5094 | 4704 |

| More than once in previous 7 days†: | |||

| Meat/fish/egg | 1278 (27.2) | 1365 (26.8) | 1246 (26.5) |

| Dairy products | 2383 (50.7) | 2536 (49.8) | 2439 (51.9) |

| Yellow fruits/vegetables | 738 (15.7) | 810 (15.9) | 790 (16.8) |

| Dark green leaves | 1752 (37.3) | 1858 (36.5) | 1803 (38.4)‡ |

| Substance use | |||

| No of women | 4702 | 5094 | 4704 |

| In previous 7 days: | |||

| Smoked cigarettes | 1307 (27.8) | 1370 (26.9) | 1397 (29.7)* |

| Drank alcohol | 385 (8.2) | 366 (7.2) | 498 (10.6)** |

| Socioeconomic status¶ | |||

| No of women | 5017 | 5448 | 5036 |

| Literate | 797 (15.9) | 714 (13.1) | 821 (16.3)** |

| Owned radios | 1415 (28.2) | 1471 (27.0) | 1455 (28.9) |

| Caste: | |||

| No of women | 4773 | 5179 | 4754 |

| Low caste or not Hindu | 826 (17.3) | 1274 (24.6) | 979 (20.6)** |

| Delivery: | |||

| No of women | 4784 | 5196 | 4813 |

| Delivered at health facility | 139 (2.9) | 151 (2.9) | 140 (2.9) |

P<0.01, **P<0.001 by χ2 test (df=2).

At first home interview during mid-trimester.

Data were missing on consumption of dark green leaves for eight women in β carotene group.

At home interview during late third trimester.

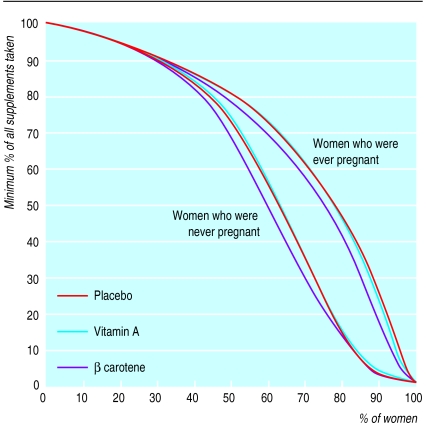

Women who were pregnant more than once during the trial received a greater percentage of their total eligible supplements than those who were never pregnant (fig 2). For example, half of the women who were ever pregnant and 44% of those who were never pregnant received ⩾80% of their intended supplements. Over 75% of the pregnant women received at least half of their eligible doses—that is, more than half of a dietary allowance for those receiving vitamin A or β carotene—compared with around 62% of those who were never pregnant. Compliance was about 3% lower in the β carotene group in the mid-range of supplement intake.

Figure 2.

Minimum percentages of all eligible weekly supplements (to the end of the trial or death) taken by percentages of women who were ever or never pregnant during the trial by supplement group

Among 1446 women who had their first pregnancy in the 27 substudy wards between September 1994 and July 1996, 1025 (71%) were seen at the clinic, of whom 978 (95%) were confirmed pregnant by urine test. From these women, serum samples were available for 935 (96%) and 916 (94%) mid-pregnancy determinations of retinol and β carotene concentrations, respectively. The mean serum retinol concentration was lowest in the placebo group (1.02 μmol/l), highest among vitamin A recipients (1.30 μmol/l), and between these two values in the β carotene group (1.14 μmol/l) (table 2). The percentage of women by supplement group with serum retinol concentrations <0.70 μmol/l followed the same pattern. The mean β carotene concentration was significantly higher (0.20 μmol/l) and the percentage of women with concentrations <0.09 μmol/l lower (26.5%) in the β carotene than in the vitamin A and placebo groups (around 0.14 μmol/l and about 42% in both groups). Thus, compliance with taking supplements seems to have been adequate to change biochemical variables.

Table 2.

Serum retinol and β carotene concentrations in women during mid-pregnancy

| Placebo | Vitamin A | β carotene | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retinol (μmol/l) | |||

| No of women | 265 | 314 | 356 |

| Mean (SD)* | 1.02 (0.35) | 1.30 (0.33) | 1.14 (0.39) |

| No (%) <0.70 μmol/l† | 51 (19) | 9 (3) | 48 (14) |

| β carotene (μmol/l) | |||

| No of women | 261 | 308 | 347 |

| Mean (SD)‡ | 0.14 (0.12) | 0.15 (0.14) | 0.20 (0.17) |

| No (%) <0.09 μmol/l¶ | 112 (43) | 130 (42) | 92 (27) |

P<0.0001 by analysis of variance; P⩽0.002 for all comparisons by t test.

P<0.0001 by χ2 test (df=2); P<0.0001 for vitamin A v placebo and vitamin A v β carotene, and P=0.052 for vitamin A v β carotene by χ2 test (all df=1).

P<0.0001 by analysis of variance; P<0.0001 for β carotene v placebo and β carotene v vitamin A, and P=0.23 for vitamin A v placebo by t test.

P<0.0001 by χ2 test (df=2); P<0.0001 for β carotene v placebo and β carotene v vitamin A, and P>0.87 for vitamin A v placebo by χ2 test (df=1).

Mortality related to pregnancy up to 12 weeks post partum was 704, 426, and 361 maternal deaths per 100 000 pregnancies in the placebo, vitamin A, and β carotene groups, yielding relative risks of 0.60 (0.37 to 0.97) (P=0.04) and 0.51 (0.30 to 0.86) (P=0.01) in the vitamin A and β carotene groups, respectively (table 3). Mortality among women receiving β carotene was not significantly different from that in the vitamin A group (relative risk 0.85 (0.48 to 1.49), P=0.57). We therefore combined the effects to obtain a relative risk of 0.56 (0.37 to 0.84), reflecting a 44% reduction in mortality related to pregnancy associated with vitamin A or β carotene supplementation (P=0.005). This survival effect was evident after 1½ years of the trial, reflected by a relative risk of 0.54 (0.32 to 0.90) (P=0.02), which remained stable during the last part of the trial (relative risk 0.61 (0.31 to 1.19), P=0.15, data not shown). The relative risk was protective for both nutritional supplements during pregnancy, from the end of pregnancy to 6 weeks post partum, and from 6 to 12 weeks post partum (table 4).

Table 3.

Impact of supplementation on mortality related to pregnancy up to 12 weeks post partum

| Placebo | Vitamin A | β carotene | Vitamin A or β carotene | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of pregnancies* | 7241 | 7747 | 7201 | 14 948 |

| No of deaths | 51 | 33 | 26 | 59 |

| Mortality (per 100 000 pregnancies) | 704 | 426 | 361 | 395 |

| Relative risk (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.60 (0.37 to 0.97) | 0.51 (0.30 to 0.86) | 0.56 (0.37 to 0.84) |

| P value | <0.04 | <0.01 | <0.005 |

Includes 157 pregnancies that were lost to follow up (43, 70, and 44 in placebo, vitamin A, and β carotene groups respectively).

Table 4.

Impact of supplementation on mortality in women during and after pregnancy

| Placebo | Vitamin A | β carotene | Vitamin A or β carotene | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of pregnancies* | 7241 | 7747 | 7201 | 14 948 |

| During pregnancy | ||||

| No of deaths | 17 | 11 | 8 | 19 |

| Mortality (per 100 000 pregnancies) | 235 | 142 | 111 | 127 |

| Relative risk (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.60 (0.26 to 1.38) | 0.47 (0.18 to 1.20) | 0.54 (0.26 to 1.11) |

| P value | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.10 | |

| 0-6 weeks post partum | ||||

| No of deaths | 26 | 18 | 16 | 34 |

| Mortality (per 100 000 pregnancies) | 359 | 232 | 222 | 227 |

| Relative risk (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.65 (0.34 to 1.25) | 0.62 (0.31 to 1.23) | 0.63 (0.36 to 1.11) |

| P value | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.11 | |

| 7-12 weeks post partum | ||||

| No of deaths | 8 | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Mortality (per 100 000 pregnancies) | 110 | 52 | 28 | 40 |

| Relative risk (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.47 (0.13 to 1.76) | 0.25 (0.04 to 1.42) | 0.36 (0.11 to 1.14) |

| P value | 0.26 | 0.12 | 0.08 |

Includes 157 pregnancies that were lost to follow up (43, 70, and 44 in placebo, vitamin A, and β carotene groups respectively).

Analysis of cause specific mortality, based on interviews with relatives, showed protective but non-significant effects of supplementation against risk of death from obstetric causes and infection (table 5). Point estimates of relative risk are stronger for β carotene than for vitamin A. Supplementation was associated with protection from death attributed to injuries and other miscellaneous causes.

Table 5.

Impact of supplementation on cause related mortality in women during pregnancy up to 12 weeks post partum. Values are numbers of women unless stated otherwise

| Cause | Placebo (n=7241) | Vitamin A (n=7747) | β carotene (n=7201) | Vitamin A or β carotene (n=14 948) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obstetric | ||||

| Haemorrhage* | 5 | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| Eclampsia | 6 | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Other† | 7 | 9 | 4 | 13 |

| Total | 18 | 17 | 10 | 27 |

| Mortality (per 100 000 pregnancies) | 249 | 219 | 139 | 181 |

| Relative risk (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.88 (0.42 to 1.81) | 0.56 (0.24 to 1.31) | 0.73 (0.38 to 1.41) |

| Infection | ||||

| Gastroenteritis | 4 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Sepsis | 5 | 5 | 2 | 7 |

| Respiratory infection | 1 | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| Other‡ | 5 | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Total | 15 | 15 | 9 | 24 |

| Mortality (per 100 000 pregnancies) | 207 | 194 | 125 | 161 |

| Relative risk (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.94 (0.42 to 2.05) | 0.60 (0.24 to 1.51) | 0.78 (0.39 to 1.58) |

| Related to injury¶ | ||||

| Total | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Mortality (per 100 000 pregnancies) | 69 | 0 | 14 | 7 |

| Relative risk (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0 | 0.20 (0.02 to 2.32) | 0.10 (0.01 to 1.14) |

| Miscellaneous | ||||

| Chronic illness§ | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Uncertain | 6 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| No information | 4 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Total | 13 | 2 | 5 | 7 |

| Mortality (per 100 000 prgnancies) | 180 | 26 | 69 | 47 |

| Relative risk (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.14 (0.03 to 0.76) | 0.38 (0.13 to 1.21) | 0.26 (0.09 to 0.73) |

Includes antepartum and postpartum haemorrhage and retained placenta.

Includes obstetric shock, postpartum shock, and obstructed labour.

Includes typhoid fever, tetanus, hepatitis, and leishmaniasis.

Includes burns, drowning, snakebite, and hanging.

Includes anaemia, asthma, and leukaemia.

The maternal mortality ratio was 645 (42 deaths/6670 live births), 407 (29/7074), and 361 (23/6643) per 100 000 live births in the placebo, vitamin A, and β carotene groups, respectively (P=0.08 for vitamin A and 0.04 for β carotene v placebo). The ratio for women receiving either vitamin A or β carotene was 385, yielding a relative risk of 0.60 (0.39 to 0.93), representing a 40% reduction in mortality by this measure (P=0.02).

Discussion

In this poor, rural Asian setting the risk of death related to pregnancy was lowered, by about 40%, among women who were routinely given dietary supplements of vitamin A or β carotene rather than placebo. Effect estimates were similar during pregnancy and post partum. The protective impact was established after 1½ years of supplementation, reflecting consistency of the effect over time and a potential duration of dosing a population by which a clear mortality reduction could be expected. The impact on mortality was similar when expressed as a maternal mortality ratio that excluded deaths related to injury and those occurring more than 6 weeks post partum. The comparability of groups of pregnant women with respect to compliance and demographic, socioeconomic, dietary, and obstetric variables shows that the observed survival effect was unlikely to have resulted from imbalances in other factors that could have influenced maternal mortality.

We intended the weekly dosage of vitamin A or β carotene to deliver the equivalent of a liberal dietary allowance of vitamin A for pregnant or lactating women.17,21 Although more than three quarters of all women who became pregnant during the trial received at least half of their recommended allowance of vitamin A through supplements, only half took 80% or more of their eligible supplements. This suggests that the risk of maternal death in populations who are deficient in vitamin A could be substantially lowered with modest increases in vitamin A or β carotene intake, as has been shown in children.22

The interview with relatives was a feasible and insightful way to investigate causes of death in a population where medical diagnoses were unobtainable; however, this method may be subject to considerable imprecision and misclassification,23,24 particularly given the complex nature of deaths related to pregnancy and the common lack of pathognomonic signs or symptoms that would be evident to lay relatives. Our interviews with relatives suggested there was a 22% reduction in infectious causes of death ((1−0.78)×100), but the finding was inconclusive. Some deaths due to infection may have been misclassified as uncertain. Eight of the 12 deaths with completed interviews (five women had been in the placebo group and three in the vitamin A and β carotene group) had reported symptoms that were consistent with infectious disease before death.

A 27% decrease in maternal mortality was attributed to obstetric causes in women receiving supplements. The effect seemed to be more strongly associated with β carotene (relative risk 0.56, P=0.18) than vitamin A (relative risk 0.88, P=0.73). Although the putative role of antioxidant defences in preventing disease25 and an in vivo antioxidant role for β carotene26 remain controversial, β carotene, acting as an antioxidant,27,28 could have reduced some forms of obstetric risk in this malnourished population. Low serum β carotene concentrations have been observed in pregnant Asian2 and African29 women with pre-eclampsia and eclampsia, whose pathogenesis entails vascular endothelial injury that may be associated with oxidative stress.30,31 Placental abruption has also been associated with depressed serum antioxidant concentrations, including β carotene.32

Currently, supplementation programmes of weekly low doses of vitamin A or β carotene do not exist for women of reproductive age, although this approach may be a cost effective way of preventing iron deficiency anaemia in the developing world.33 Our findings suggest that raising the intake of preformed vitamin A or provitamin A carotenoids towards the values recommended for pregnancy or lactation, presumably by supplementation or by dietary means, can complement antenatal and essential obstetric services in lowering maternal mortality in rural south Asia.

Acknowledgments

The NNIPS-2 (Nepal Nutrition Intervention Project-Sarlahi) Study Group includes (in addition to the authors) Drs Ramesh Adhikari, Bhakta Raj Dahal, Michele Dreyfuss, Rebecca Stoltzfus, James Tielsch, and Sedigheh Yamini-Roodsari; Noor Nath Acharya, Dev N Mandal, Kerry Schulze, Tirtha R Shakya, Lee Shu-Fune Wu, Andre Hackman, and Gwendolyn Clemens.

We thank Drs Frances Davidson, Victor Barbiero, Tim Quick, Martin Frigg, James Tonascia, Frederick Trowbridge, Calvin Willhite, and David Calder; Molly Gingerich, Charles Llewellyn, David Peat, Lisa Gautschi, Ravi Ram, and more than 550 staff of the NNIPS-2 study for their help.

Editorial by Olsen

Footnotes

Members of the study group are given at the end of the article

Funding: The NNIPS-2 trial was a collaboration (cooperative agreement No HRN-A-00-97-00015-00) between the Center for Human Nutrition and the Sight and Life Institute in the Department of International Health at the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health and the National Society for Comprehensive Eye Care (Nepal Netra Jyoti Sangh), Kathmandu, Nepal. It was supported by the Office of Health and Nutrition, US Agency for International Development (USAID), Washington, DC, and assisted by the Sushil Kedia Foundation, Sarlahi, Nepal. The capsules were provided by Roche, Basle, as part of its Task Force Sight and Life project.

Conflict of interest: KPW and AS have received funds to support vitamin A research in the developing world from Task Force Sight and Life, Roche, Basle. The Center for Human Nutrition has received an endowment from Roche to establish a Sight and Life Institute for conducting micronutrient research related to child and maternal health and survival.

References

- 1.Sivakumar B, Panth M, Shatrugna V, Raman L. Vitamin A requirements assessed by plasma response to supplementation during pregnancy. Int J Vit Nutr Res. 1997;67:232–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basu RJS, Arulanantham R. A study of serum protein and retinol levels in pregnancy and toxaemia of pregnancy in women of low socio-economic status. Indian J Med Res. 1973;61:589–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah RS, Rajalakshmi R, Bhatt RV, Hazra MN, Patel BC, Swamy NB, et al. Liver stores of vitamin A in human fetuses in relation to gestational age, fetal size and maternal nutritional status. Br J Nutr. 1987;58:181–189. doi: 10.1079/bjn19870085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jayasekera JPDJS, Atukorala TMS, Seneviratne HR. Vitamin A status of pregnant women in five districts of Sri Lanka. Asia-Oceania J Obstet Gynaecol. 1991;17:217–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.1991.tb00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panth M, Shatrugna V, Yasodhara P, Sivakumar B. Effect of vitamin A supplementation on haemoglobin and vitamin A levels during pregnancy. Br J Nutr. 1990;64:351–358. doi: 10.1079/bjn19900037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christian P, West KP, Jr, Khatry SK, Katz J, LeClerq S, Pradhan EK, et al. Vitamin A or β-carotene supplementation reduces but does not eliminate maternal night blindness in Nepal. J Nutr. 1998;128:1458–1463. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.9.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morse EH, Clarke RP, Keyser DE, Merrow SB, Bee DE. Comparison of the nutritional status of pregnant adolescents with adult pregnant women. I. Biochemical findings. Am J Clin Nutr. 1975;28:1000–1013. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/28.9.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sommer A, West KP., Jr . Vitamin A deficiency: health, survival, and vision. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Underwood BA. Maternal vitamin A status and its importance in infancy and early childhood. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;59:517–24S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/59.2.517S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dimenstein R, Trugo NMF, Donangelo CM, Trugo LC, Anastacio AS. Effect of subadequate maternal vitamin-A status on placental transfer of retinol and beta-carotene to the human fetus. Biol Neonate. 1996;69:230–234. doi: 10.1159/000244315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fawzi WW, Msamanga GI, Spiegelman D, Urassa EJN, McGrath N, Mwakagile D, et al. Randomised trial of effects of vitamin supplements on pregnancy outcomes and T cell counts in HIV-1-infected women in Tanzania. Lancet. 1998;351:1477–1482. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)04197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green HN, Pindar D, Davis G, Mellanby E. Diet as a prophylactic agent against puerperal sepsis. BMJ. 1931;ii:595–598. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.3691.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.West KP, Jr, Christian P. Maternal night blindness: extent and associated risk factors. IVACG statement. Washington, DC: International Vitamin A Consultative Group; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christian P, West KP, Jr, Khatry SK, Katz J, Shrestha SR, Pradhan EK, et al. Night blindness of pregnancy in rural Nepal—nutritional and health risks. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27:231–237. doi: 10.1093/ije/27.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Christian P, Schulze K, Stoltzfus RJ, West KP., Jr Hyporetinemia, illness symptoms, and acute phase protein response in pregnant women with and without night blindness. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67:1237–1243. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/67.6.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Semba RD. Vitamin A, immunity and infection. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:489–499. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.3.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Research Council. Recommended dietary allowances. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1989. pp. 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahn HA, Sempos CT. Statistical methods in epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCullagh P, Nelder JA. Generalized linear models. 2nd ed. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katz J, Zeger SL, Tielsch JM. Village and household clustering of xerophthalmia and trachoma. Int J Epidemiol. 1988;17:865–869. doi: 10.1093/ije/17.4.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tee E-S, Florentino R. Current status of recommended dietary allowance in Southeast Asia: a regional overview. Nutr Rev. 1998;56:510–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1998.tb01709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muhilal, Permeisih D, Idjradinata YR, Muherdiyantiningsih, Karayadi D. Vitamin A-fortified monosodium glutamate and health, growth, and survival of children: a controlled field trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988;48:1271–1276. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/48.5.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ronsmans C, Vanneste AM, Chakraborty J, Van Ginneken J. A comparison of three verbal autopsy methods to ascertain levels and causes of maternal deaths in Matlab, Bangladesh. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27:660–666. doi: 10.1093/ije/27.4.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anker M. The effect of misclassification error on reported cause-specific mortality fractions from verbal autopsy. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26:1090–1096. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.5.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halliwell B. Free radicals, antioxidants, and human disease: curiosity, cause or consequence? Lancet. 1994;344:721–724. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92211-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crabtree DV, Adler AJ. Is β-carotene an antioxidant? Med Hypotheses. 1997;48:183–187. doi: 10.1016/s0306-9877(97)90286-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burton GW, Ingold KU. β-carotene: an unusual type of lipid antioxidant. Science. 1984;224:569–573. doi: 10.1126/science.6710156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allard JP, Royall D, Kurian R, Muggli R, Jeejeebhoy KN. Effects of β-carotene supplementation on lipid peroxidation in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;59:884–890. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/59.4.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ziari SA, Mireles VL, Cantu CG, Cervantes M, III, Idrisa A, Bobsom D, et al. Serum vitamin A, vitamin E, and beta-carotene levels in preeclamptic women in Northern Nigeria. Am J Perinatol. 1996;13:287–291. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-994343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hubel CA, Roberts JM, Taylor RN, Musci TJ, Rogers GM, McLaughlin MK. Lipid peroxidation in pregnancy: New perspectives on preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161:1025–1034. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90778-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davidge ST, Hubel CA, Brayden RD, Capeless EC, McLaughlin MK. Sera antioxidant activity in uncomplicated and preeclamptic pregnancies. Obst Gynecol. 1992;79:897–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma SC, Bonnar J, Dostaova L. Comparison of blood levels of vitamin A, β-carotene and vitamin E in abruptio placentae with normal pregnancy. Int J Vit Nutr Res. 1986;56:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beard JL. Weekly iron intervention: the case for intermittent iron supplementation. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68:209–212. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]