Abstract

We examined whether support underprovision (receiving less support than is desired) and support overprovision (receiving more support than is desired) should be examined as qualitatively distinct forms of inadequate support in marriage. Underprovision of partner support, overprovision of partner support, and marital satisfaction were assessed five times over the first five years in a sample of newlywed husbands and wives (N = 103 couples), and were analyzed via actor-partner interdependence modeling (APIM) and growth curve analytic techniques. Increases in underprovision and overprovision of support were each uniquely associated with declines in marital satisfaction over the first five years of marriage; however, overprovision of support was a greater risk factor for marital decline than underprovision. Further, when examining support from a multidimensional perspective, overprovision was at least as detrimental, if not more detrimental, than underprovision for each of four support types (i.e., informational, emotional, esteem, and tangible support). The present study is the first to examine the utility of differentiating between underprovision and overprovision of partner support. Theoretical, empirical, and clinical implications are discussed.

Keywords: APIM, couples, GCA, marriage, support, support adequacy

A new era of marital research has emerged over the last two decades demonstrating that supportive exchanges between spouses significantly contribute to the developmental course of marital satisfaction (see Bradbury, Fincham, & Beach, 2000 for review)1. Consistent with a social learning model, individuals are generally more satisfied with their marriages to the extent that they receive greater support from their spouses (e.g., Abbey, Andrews, & Halman, 1995). However, individuals have unique support needs, and more frequent support is not always preferable (e.g., Cutrona, Cohen, & Igram, 1990; Cutrona & Suhr, 1992). Accordingly, researchers have begun transitioning from exclusively assessing quantity of support received to also examining quality of support received. Within the marital field, inadequate support (the mismatch between desired and received frequencies of support behaviors; Dehle et al., 2001) has been identified as a factor contributing to marital discord. Acknowledging that more frequent partner support is not always beneficial is an important step toward clarifying the nature and functional role of support processes in marriage. However, this new area of research is limited because it has been guided by an implicit assumption that inadequate support is a unitary, continuous construct. More specifically, existing measures of support inadequacy do not operationalize support underprovision (not receiving enough support) and support overprovision (receiving too much support) as distinct constructs. The purpose of the present study was to empirically examine the validity of this assumption in order to determine whether inadequate support is indeed a unitary construct or, alternatively, whether under- and overprovision are qualitatively distinct forms of inadequate support with unique implications for marriage.

Support Adequacy in Marriage: Underprovision versus Overprovision of Support

Regardless of whether there are distinct forms of inadequate support, there is a general consensus that simply receiving support is insufficient for enhancing marital quality. One explanation for why simply receiving support may be insufficient can be derived from optimal matching theory (Cutrona, 1990; Cutrona & Russell, 1990), in which certain types of support are viewed as more beneficial than others for coping with certain types of stressors. Support may not be desirable if the type of support being provided does not match the stressful circumstances being faced by the support recipient. Attempts to demonstrate the benefits of optimal matching in this way (matching specific types of support with specific stressors) have yielded inconsistent results (e.g., Cutrona & Suhr, 1992), suggesting that it may be worth re-examining this theory. Numerous factors beyond the context of a problem contribute to individual support needs. First, the nature of the relationship between a support recipient and provider can influence whether or not an individual perceives the support as beneficial. For example, greater intimacy with a support provider is associated with greater satisfaction with received support (e.g., Cutrona, Cohen, & Igram, 1990). Second, characteristics of the support recipient such as attributional style (Beach, Fincham, Katz, & Bradbury, 1996; Fincham & Bradbury, 1990), locus of control (Lefcourt, Martin, & Saleh, 1984), attachment orientation (Newcomb, 1990), and personality characteristics (Cutrona, Hessling, & Suhr, 1997; Lefcourt et al.) also contribute to individual support needs. Therefore, matching support to the unique needs of the support recipient rather than to the problem with which the recipient is coping might better promote quality support provision. Indeed, optimal matching theorists – though historically focused on matches between support and stress – recognize that individuals have specific support needs that are influenced by multiple factors (e.g., Cutrona, Shaffer, Wesner, & Gardner, 2007).

The utility of matching support to the person rather than to the problem has already been recognized by researchers examining support adequacy in marriage. Within these studies, support recipients indicate whether they prefer more, less, or the same amount of specific support behaviors that they have received, and support is considered inadequate to the extent that there is a mismatch between desired and received levels of support. Adequacy of partner support is associated with concurrent marital satisfaction (Dehle et al.), interacts with stress to protect and promote marital satisfaction (Brock & Lawrence), and accounts for more variance in marital satisfaction than support frequency (albeit only for husbands; Lawrence et al., 2008).

Two forms of inadequate support can occur during a support transaction: underprovision of support and overprovision of support. Underprovision occurs when an individual does not receive enough of the support he or she desires. For example, support that has been provided may be noticed by a support recipient, but the behaviors (a) may be viewed as insufficient in quantity by the support recipient or (b) may not be the type of support the individual desires. Overprovision occurs when an individual receives too much support relative to what he or she desires. For example, support may be provided and noticed by the recipient, but the recipient (a) may prefer a smaller quantity of the type of support provided, (b) may not desire any of the type of support provided, (c) may prefer to receive a different type of support altogether (e.g., emotional instead of instrumental support), or (d) may not wish to receive any support at all (e.g., prefer to cope with the problem on his or her own by withdrawing from social interaction).

When examining the role of inadequate support in marriage, researchers have historically taken one of two approaches. The first approach is to collapse under- and overprovision together in order to attain one global support inadequacy score (e.g., Brock & Lawrence, 2008). To the extent that individuals receive more or less support than they desire, support is less adequate. The second approach is to code inadequate support on a continuum from under- to overprovision, with adequate support falling in the middle and representing an exact match between desired and received levels of support (e.g., Dehle et al., 2001). In both approaches, inadequate support is operationalized as a unitary, continuous construct rather than as comprising two qualitatively distinct forms of inadequate support: under- and overprovision. The implicit assumption that inadequate support is a unitary construct is analogous to the assumptions researchers once made regarding (a) positive and negative affect and (b) positive and negative marital quality. Historically, both sets of constructs were operationalized as two poles of a single dimension. Once these assumptions were examined statistically (by Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988, and Fincham & Linfield, 1997, respectively), researchers began to operationalize them as orthogonal constructs, which in turn led to a more refined understanding of the distinct factors contributing to individual and dyadic well-being. We argue that the same potential benefits may be gained by examining under- and overprovision of support as qualitatively distinct constructs.

A Brief Review of Relevant Theories

The purpose of the present study was to examine the utility of operationalizing under- and overprovision of support as separate constructs. However, a review of relevant theories and research is necessary for us to determine whether it makes sense conceptually to differentiate between each form of inadequate support in marital research. Stress and coping research, equity theory, and reactance theory provide frameworks for understanding how and why each form of inadequate support might differentially affect marital satisfaction. We consider (a) the unique mechanisms through which under- and overprovision may influence marital satisfaction, and (b) whether one type of inadequate support might be more detrimental to marriage than the other.

Stress and coping research

Within the stress and coping literature, intimate partner support is considered a vital resource for individuals coping with stress (Beach, Martin, Blum, & Roman, 1993). Consequently, inadequate partner support may greatly undermine one’s coping efforts, which in turn may have negative consequences for marital satisfaction. Underprovision of support that is needed to effectively cope with a problem (e.g., not enough tangible assistance) may result in partners being viewed as unreliable sources of coping assistance. If support recipients view their partners as undependable, they may become less satisfied with their marriages. In contrast, overprovision of the “wrong” kind of support for handling a problem (e.g., too much advice) might actively interfere with coping efforts. For example, support recipients may feel guilty if they do not embrace unhelpful support that has been provided, which in turn may detract from one’s ability to attend to coping efforts. In addition, overprovision of partner support may generate additional stressors with which to contend. For instance, if support is not embraced, the support provider may feel rejected, disrespected, and/or unappreciated, which may lead to increased marital conflict or decreased emotional intimacy. If support overprovision interferes with one’s coping efforts, enhances conflict, and/or decreases intimacy, it is likely that one’s global marital satisfaction will also be impacted, perhaps to a greater extent than it would be as a result of support underprovision.

The stress and coping literature also suggests that the negative impact of support underprovision on marriage may be buffered in a way that overprovision cannot be buffered. Although support underprovision can hinder one’s coping efforts, these consequences may be buffered by receiving support from sources outside of the marriage. If support that is necessary to effectively engage in coping efforts can be attained elsewhere, individuals may not become increasingly dissatisfied with their marriages. In contrast, seeking support outside of the marriage would not undo the negative effects of overprovision on marriage (e.g., unwanted support interfering with coping efforts, increased marital conflict, lower intimacy). In sum, based on the stress and coping literature, under- and overprovision would likely impact marital satisfaction through unique mechanisms, yet overprovision has the potential to be more detrimental to marriage.

Equity theory

Equity theory proposes that, by nature, humans monitor the extent to which they receive equal outcomes (reward and costs) relative to members of their social networks (Walster, Berscheid, & Walster, 1973). The application of equity theory to the study of support processes in marriage suggests that individuals may report underprovision when they have received less support than they have provided to their partners during past exchanges. If support recipients believe that they are entitled to more support than they have received - and, therefore, perceive themselves as not being treated fairly in their relationships - they may become increasingly dissatisfied with their marriages. Conversely, individuals might report overprovision of support when they have received more support that they have provided to their partners in the past. If support recipients believe that they are not deserving of the support they have received from their spouses - because they have not provided a fair amount of support in return - recipients may feel obligated to reciprocate support or might experience distrust regarding the motives behind their partners’ generosity (Cutrona, 1996), which in turn may have consequences for global marital satisfaction. In sum, equity theory suggests that under- and overprovision are likely to impact marital satisfaction through unique mechanisms, but provides no indication of whether one form of inadequate support may be more detrimental to marriage than the other.

Reactance theory

Whereas the stress and coping literature and equity theory provide frameworks for conceptualizing how and why both under- and overprovision influence marital satisfaction, reactance theory speaks specifically to the role of overprovision in marriage. Reactance theory suggests that conditions threatening one’s behavioral freedom (e.g., when someone dictates how a person should act) result in a motivational state known as psychological reactance, which is associated with a strong impulse to regain behavioral freedom (Brehm, 1966). Some forms of support overprovision (e.g., advice giving, completing a task for an individual) may be viewed as insensitive or patronizing, or interpreted as implying that the recipient is incompetent or unable to handle a problem alone. Such interpretations would likely lead to psychological reactance, as well as to resentment toward or disappointment in one’s partner (Cutrona, Cohen, & Ingram, 1990; Coyne & DeLongis, 1986; Dehle et al, 2001). Emotional distancing strategies and/or psychological aggression (e.g., contempt, criticizing one’s partner in front of others) may ensue and contribute to marital discord. In sum, reactance theory offers insight into how overprovision might negatively impact marriage, and suggests that overprovision of support may be especially detrimental to marriage.

A multidimensional model of support

A multidimensional model asserts that support is comprised of a general support dimension that can be further differentiated into distinct support types. We believe that in order to best understand the role of inadequate support in marriage, we must examine under- and overprovision of support within a multidimensional framework. Cutrona and Russell (1990) have identified five theoretically-based dimensions of support: informational (advice or guidance), emotional (comfort or security), esteem (confidence in one’s ability to handle a problem), tangible (indirect or direct instrumental assistance), and network support (sense of belonging to an interpersonal network). Informational and tangible support types have been conceptualized as forms of action-facilitating support, as they involve actively trying to solve a problem Cutrona & Suhr, 1992; Thoits, 1995). In contrast, emotional and esteem support types have been conceptualized as forms of nurturant support, as they are intended to comfort an individual who is coping with a problem (Cutrona & Suhr; Thoits).

As previously stated, overprovision of support is expected to lead to psychological reactance (Brehm, 1966). By employing a multidimensional perspective, we can begin to conceptualize the conditions under which overprovision of support might be more detrimental to marriage than underprovision. Specifically, psychological reactance is most likely to occur in response to the overprovision of action-facilitating support, which includes telling the support recipient how to act (informational support) or taking charge of solving the problem (tangible support). Given that psychological reactance - and subsequent oppositional behavior and aggression – is expected to have negative consequences for marriage, overprovision of action-facilitating support should be especially detrimental to marriage.

Summary

By examining inadequate support within multiple theoretical frameworks, it appears that both under- and overprovision may negatively influence marital satisfaction, albeit through different mechanisms. Therefore, it makes sense conceptually to differentiate between each form of inadequate support in marital research. Further, a review of theory and research suggests that overprovision might actually be more detrimental to marriage than underprovision. Within a stress and coping framework, both under- and overprovision of support are expected to hinder one’s coping efforts, but the negative consequences of underprovision may be buffered by receiving support from sources outside of the marriage. In addition, overprovision may lead to psychological reactance – especially for action-facilitating support types – which in turn is likely to have negative consequences for marriage (e.g., resentment toward one’s partner, emotional distancing, psychological aggression).

The Present Study

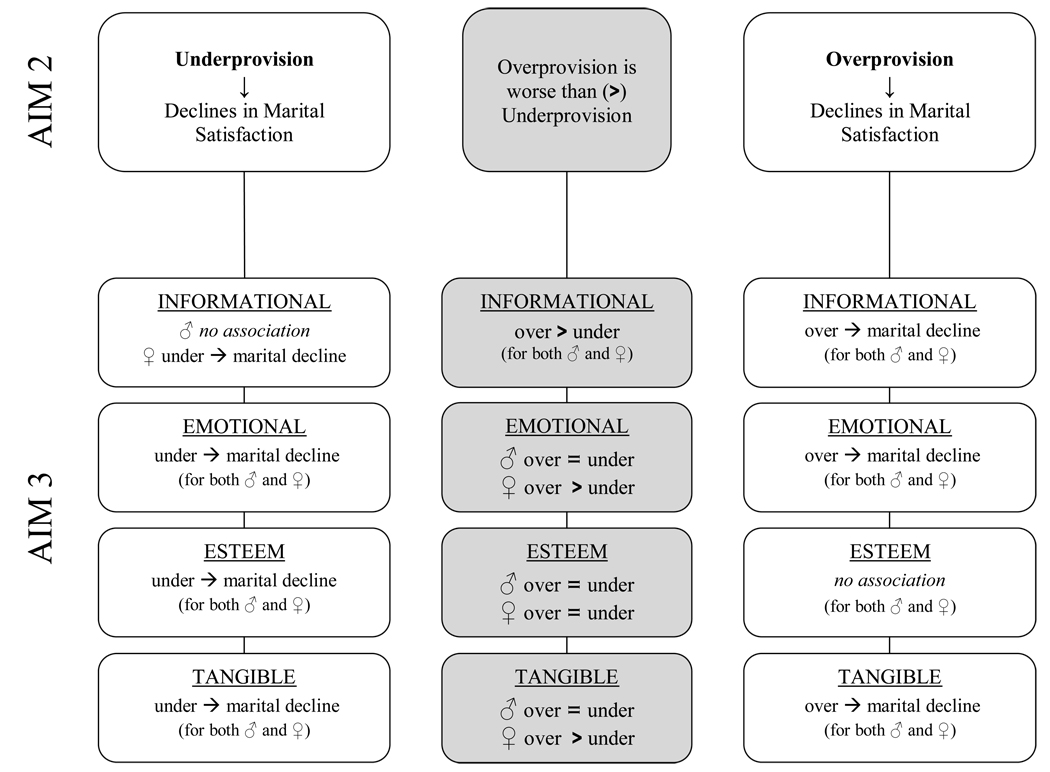

The principal goal of the present study was to challenge the assumption that inadequate support is a unitary, continuous construct. If under- and overprovision are both uniquely associated with marital satisfaction and differ in their strengths of association with marital satisfaction, then examining them as qualitatively distinct aspects of inadequate support should provide a more complete understanding of support processes in marriage. In pursuit of this goal, we examined three aims in the present study. The first aim was to clarify the nature of under- and overprovision of support in marriage. We examined prevalence rates, mean levels, variances, and longitudinal courses of under- and overprovision as preliminary support for our contention that under- and overprovision are qualitatively distinct. For example, we expected relatively low correlations between under- and overprovision, and expected different trajectories of change for under- versus overprovision over time. The second aim was to directly compare the consequences of under- versus overprovision of support for marriage. In line with our assertion that under- and overprovision of support impact marriage through unique mechanisms (by interfering with coping efforts and contributing to perceptions of inequity in one’s marriage), we expected trajectories of under- and overprovision (greater escalations over time) to each be uniquely associated with greater marital decline. Further, overprovision of support was expected to pose a significantly greater risk for marital decline than underprovision given that (a) the negative consequences of underprovision may be buffered by support received from sources outside of the marriage, (b) seeking support outside of the marriage would not undo the negative effects of overprovision on marriage, and (c) overprovision may lead to psychological reactance.

Consistent with a multidimensional framework, the third aim was to directly compare the consequences of under- versus overprovision for distinct support types. Not only did we expect overprovision to be more detrimental for marriage than underprovision, but we also expected the strength of this finding to vary as a function of support type. Four support types were examined in the present study: informational, emotional, esteem, and tangible support2. Based on reactance theory (Brehm, 1966), overprovision of action-facilitating support (tangible and information) has the potential to trigger aggressive behaviors from the support recipient. Thus, we predicted that overprovision of informational and tangible support would be more detrimental for marriage than underprovision of these support types. In contrast, overprovision of nurturant support (emotional and esteem) was not expected to trigger psychological reactance, so we expected under- and overprovision of esteem and emotional support to be similarly detrimental to marriage.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Participants were recruited through marriage license records in Iowa. Couples in which both spouses were at least 18 years of age were mailed letters inviting them to participate, and 350 couples responded. Interested couples were screened over the telephone to ensure that they were married less than six months and in their first marriages. The first 105 couples who completed the screening procedures, were deemed eligible, and were able to schedule their initial laboratory appointments were included in the sample. Of the 105 couples who participated, one couple’s data were deleted because it was revealed during the laboratory session that it was not the wife’s first marriage. The data from the husband of another couple were removed because his responses were deemed unreliable. Couples dated an average of 44 months (SD = 27) prior to marriage, 76% cohabited premaritally, and 15% identified themselves as ethnic minorities. (The proportion of non-Caucasians in Iowa is 7%; U.S. Census Bureau). Modal annual joint income ranged from $40,001– $50,000. Husbands’ average age was 25.82 (SD = 3.55), and wives’ average age was 24.78 (SD = 3.67). Modal years of education was 14 for both spouses.

Eligible couples completed questionnaires through the mail five times during the first five years of marriage: at 3–6 months (Time 1), at 12–15 months (Time 2), at 21–24 months (Time 3), at 30–33 months (Time 4), and at 54–57 months after the wedding (Time 5). All measures included in the present study were completed by husbands and wives at all time points. At Time 1, couples also came into the laboratory to complete a series of procedures beyond the scope of the current study. At all time points, couples were instructed to complete measures independently and were provided with separate, stamped envelopes in which to seal and mail back their completed questionnaires. Couples were paid $100 for participation at Time 1, $50 per wave of data collection at Times 2–4, and $25 at Time 5. By the 5th wave of data collection, 12 couples had permanently separated or divorced and three couples had withdrawn from the study; however, available data from these couples were included in the present study.

Measures

Support in Intimate Relationships Rating Scale (SIRRS; Dehle et al., 2001)

The SIRRS is a 48-item, self-report measure of received partner support. It assesses support across a wide range of support behaviors, focuses on support from partners in intimate relationships, emphasizes the perceived adequacy of the support received, and is anchored in behaviorally specific indicators. In the original version of the SIRRS, specific counts of actual and preferred rates of support behaviors were recorded over seven consecutive days. However, we sought to investigate changes in global perceptions of support adequacy rather than specific counts of support, and we were interested in changes in support adequacy over longer intervals (e.g., weeks to months at a time rather than daily). Therefore, we modified the instructions so that spouses estimated the frequencies of specific supportive behaviors provided by their partners over the past month (never, rarely, sometimes, often, almost always) and then indicated a preferred global frequency for each behavior (more, less, or the same). The revised measure demonstrated strong reliability (internal consistency, factorial fit) and validity (convergent, divergent, and incremental predictive validity) in dating and married relationships, across men and women, and across time (Barry, Bunde, Brock, & Lawrence, in press). In the present sample, αs for scores representing preferred frequencies ranged from .94 to .97 for husbands and wives across time. Scores representing underprovision of support were attained by calculating the proportion of the 48 support behaviors an individual indicated he or she would prefer more of, resulting in a score ranging from 0–1. Scores representing the degree of overprovision of support were similarly attained by computing the proportion of items scored less by a participant, resulting in a score ranging from 0–1. For example, if a husband indicated that he would prefer more of 20 support behaviors and less of 10 support behaviors (and that he would prefer the same amount of support for the remaining 18 behaviors), his score for underprovision would be .42 (20 divided by 48) and for overprovision would be .21 (10 divided by 48 total items).

Support behaviors included in the SIRRS represent the five types of support offered by Cutrona and Russell (1990): informational, emotional, esteem, tangible, and network support. In addition to computing proportion scores representing under- and overprovision, we also computed under- and overprovision scores for each type of support (proportion of behaviors indicative of a specific support type that were scored more or less, respectively). Alphas ranged from .76–.88 for informational, .89–.93 for emotional, .83–.91 for esteem, .86–.94 for tangible, and .50–.88 for network support. Given that the reliability coefficients for network support were less than < .70 at multiple time points, network support was excluded from analyses.

Quality of Marriage Index (QMI; Norton, 1983)

The QMI is a 6-item, self-report questionnaire designed to assess the “essential goodness of a relationship.” Participants indicate the extent to which they agree or disagree with 5 items using a scale from 1 (very strong disagreement) to 7 (very strong agreement), and rate their global marital “happiness” on a scale from 1 (very unhappy) to 10 (perfectly happy). Alphas ranged from .91 to .97 for husbands and wives over time. Scores were summed each time to generate trajectories of marital satisfaction.

Data Analyses

Growth curve modeling techniques (GCM; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2001) and an APIM for mixed independent variables (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006) were used in the present study. Continuous variables were group mean centered at Level 1. All parameters (intercepts and slopes) were estimated simultaneously. The possibility of interdependence between husbands’ and wives’ data was incorporated into our analyses in four ways. First, when dyad members are distinguishable, as in our sample of heterosexual married couples, there are potentially two actor effects and two partner effects; all four paths were included in analyses unless otherwise noted. Second, correlations between husbands’ and wives’ predictors were estimated in all equations. Third, the residual non-independence in outcome scores is represented by the correlation between the error terms in husbands’ and wives’ outcomes, and was estimated in all equations. Fourth, we ran chi-square tests to assess the homogeneity of husbands’ versus wives’ Level 1 variance for each baseline model. When this chi-square test was significant, those residual terms were entered as simultaneous outcomes of all relevant predictors in subsequent models.

Results

Husbands reported significantly greater marital satisfaction than wives (averaged across time: t(101) = 16.94, p < .001; husbands, M = 39.19, SD = 5.34; wives, M = 33.12, SD = 4.61); there were no other sex differences in mean levels of our variables. Interspousal correlations were generally small to medium (rs ranged from .01 – .37), with one exception: consistent with the literature on newlywed couples (e.g., Karney & Bradbury, 1995), rates of marital satisfaction between spouses were highly correlated (r = .75). Both within-husband and within-wife correlations between (a) overprovision and marital satisfaction and (b) underprovision and marital satisfaction ranged from .02 to .55. Therefore, our predictors and outcomes were sufficiently distinct from each other to warrant examining them as separate (albeit related) constructs. The average within-scale correlation for underprovision (e.g., underprovision of informational and underprovision of esteem support) was .74, and the average within-scale correlation for overprovision was .51. Large correlations were expected given that each type of support is nested within a higher-order general support factor (Cutrona & Russell, 1990).

A quadratic model best fit the data for husbands’ and wives’ marital satisfaction. (See Brock & Lawrence, 2008 for details of the analyses conducted to compare linear and quadratic models.) Husbands’ and wives’ marital satisfaction declined over the first 15 months of marriage and then remained relatively stable through the fifth year of marriage (husbands’ slopes: t(101) = 2.58, p < .000; wives’ slopes: t(101) = 11.53, p < .000). Thus, greater curvilinear change (slope estimates with larger coefficients) is indicative of a more favorable course of marital satisfaction -- more stabilization as opposed to continued decline through the second to fifth years of marriage. In contrast, less curvilinear change (slope estimates with smaller coefficients) indicates a less favorable course of marital satisfaction – continued linear decline rather than a “leveling off” of marital satisfaction in the second year of marriage.

Aim 1: What is the Nature of Under- and Overprovision of Support in Newlywed Marriage?

Descriptive statistics for underprovision

Approximately two-thirds of husbands reported receiving less support than they desired (i.e., husbands’ underprovision) and almost all wives reported receiving less support than they desired (i.e., wives’ underprovision) at some point during the first five years of marriage; percentages ranged from 61.4% to 71.3% for husbands and from 81.4% to 91.9% for wives across the five time points. Proportional scores were computed between 0.00 and 1.00 for each type of support. Across the 5 time points and the 4 types of support, mean proportional scores ranged from .21 (SD = .21) to .51 (SD = .28) for husbands and from .31 (SD = .25) to .57 (SD = .31) for wives. On average, there was a trend toward a linear decline in underprovision over time (t = −1.01 for husbands; t = − 1.04 for wives). Further, there was significant between-subject variability in linear trajectories of underprovision for wives (χ2(92) = 175.60, p < .001). Averaging across time, underprovision of support did not occur at a greater rate for any particular type of support for husbands; however, wives reported significantly more underprovision of emotional, esteem, and tangible support than informational support (ts ranged from 3.78 to 6.04, ps < .001). Wives’ mean levels of underprovision of emotional, esteem, and tangible support did not differ from one another.

Descriptive statistics for overprovision

One-third to one-half of husbands (27.1% to 40.8%) and wives (32.6% to 43.4%) reported receiving more support than they desired (i.e., husbands’ overprovision and wives’ overprovision, respectively) in the early years of marriage. Across the five time points and the four types of support, mean proportional scores ranged from .07 (SD = .02) to .36 (SD = .01) for husbands and from .07 (SD = .04) to .34 (SD = .22) for wives. There was a trend toward escalation in overprovision over time (t = .80 for husbands; t = .79 for wives), and there was significant between-subject variability in linear trajectories of support overprovision for husbands (χ2(93) = 570.83, p < .001) and wives (χ2(93) = 565.96, p < .001). Husbands reported significantly more overprovision of informational support than any other type (ts ranged from 2.95 to 4.10, ps < .005). Husbands also reported greater overprovision of emotional support relative to esteem (t(102) = 4.14, p < .001) and tangible support (t(102) = 2.85, p < .01) . Wives’ results followed the same pattern; they reported significantly more overprovision of informational support than any other support type (ts ranged from 3.95 to 5.05, ps <.001). Wives also reported greater overprovision of emotional support relative to esteem (t(102) = 4.03, p < .001) and tangible support (t(102) = 1.96, p < .05). Mean levels of overprovision of esteem and tangible support did not differ for husbands or wives.

Comparing underprovision to overprovision

Averaged across time, correlations between scores of underprovision and scores of overprovision were generally small, ranging from .02 – .33. Spouses reported significantly more under- than overprovision of support (husbands: t(102) = 7.04, p < .001; wives: t(102) = 12.28, p < .001). This pattern remained the same regardless of whether we collapsed across types of support or examined each type of support individually (ts(102) ranged from 4.17 to 7.31 for husbands and from 6.17 to 12.34 for wives, ps < .001).

Sex differences

On average, wives reported significantly more underprovision of support than husbands (t(102) = −6.139, p < .001). Husbands and wives did not differ significantly in their reports of overprovision. With regard to specific support types, wives reported significantly more underprovision of emotional, esteem, and tangible support than husbands did (ts ranged from 4.49 to 6.10, ps < .001). Husbands and wives did not differ in reported underprovision of informational support. Husbands and wives did not differ in reports of any type of overprovision.

Aim 2: Are Under- or Overprovision Uniquely Associated with Marital Satisfaction?

The second aim was to identify whether under- and overprovision of support were uniquely associated with marital satisfaction, and whether one form of inadequate support accounts for more variance in trajectories of marital satisfaction than the other. Full scale underprovision of support (i.e., collapsing across support types) and full scale overprovision of support were entered as time-varying covariates at Level 1: Yij (Marital Satisfaction) = β1j (Husband) + β2j (Wife) + β3j (H Linear Slope) + β4j (W Linear Slope) + β5j (H Quadratic Slope) + β6j (W Quadratic Slope) + β7j (H Underprovision) + β8j (W Underprovision) + β9j (H Overprovision) + β10j (W Overprovision) + rij. (All cross-spouse paths were also estimated but are not shown here for ease of presentation.) Error terms for covariates were fixed so that the model would converge (i.e., β7j – β10j). As presented in Table 1, rates of change in husbands’ underprovision of support (the extent to which husbands received less support than they desired) were uniquely and significantly associated with rates of change in their own marital satisfaction (t(101) = −3.92, p < .001). To the extent that underprovision increased over time, husbands experienced greater linear decline in marital satisfaction. In addition, rates of change in husbands’ overprovision of support (the extent to which husbands received more support than they desired) were also uniquely and significantly associated with rates of change in their own marital satisfaction (t(101) = −2.88, p < .01). To the extent that husbands’ overprovision increased over time, they experienced greater declines in marital satisfaction. Wives demonstrated a similar pattern; increases in underprovision (t(101) = −4.84, p < .001) and increases in overprovision (t(101) = −3.38, p < .005) were each uniquely and significantly associated with marital decline. See Figure 1 for a visual depiction of these results.

Table 1.

Associations between Rates of Change in Under- & Overprovision of Received Support and Recipients’ Marital Satisfaction

| Aim 2: Support Received➔Marital Satisfaction | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underprovision➔Marital Satisfaction | Overprovision➔Marital Satisfaction | Under vs. Over | |||||||

| Coefficient | SE | t(101) | Eff. size r | Coefficient | SE | t(101) | Eff. size r | χ2 (1) | |

| Husbands | −7.52 | 1.92 | −3.92**** | .36 | −18.73 | 6.52 | −2.88** | .28 | 4.76* |

| Wives | −8.02 | 1.66 | −4.84**** | .43 | −27.14 | 8.03 | −3.38*** | .31 | 5.00* |

| Aim 3: Types of Support Received➔Marital Satisfaction | |||||||||

| Underprovision➔Marital Satisfaction | Overprovision➔Marital Satisfaction | Under vs. Over | |||||||

| Coefficient | SE | t(101) | Eff. size r | Coefficient | SE | t(101) | Eff. size r | χ2 (1) | |

| Informational | |||||||||

| Husbands | −1.28 | 0.74 | −1.73 | .17 | −8.05 | 3.02 | −2.67** | .26 | 5.03* |

| Wives | −3.69 | 0.96 | −3.83**** | .36 | −8.82 | 2.43 | −3.64*** | .34 | 4.07* |

| Emotional | |||||||||

| Husbands | −4.94 | 1.50 | −3.29*** | .31 | −11.06 | 4.38 | −2.53* | .24 | 1.78 |

| Wives | −6.59 | 1.15 | −5.73**** | .50 | −21.97 | 4.39 | −5.01**** | .45 | 11.37*** |

| Esteem | |||||||||

| Husbands | −5.58 | 1.10 | −5.04**** | .45 | −7.09 | 5.24 | −1.35 | .13 | .08 |

| Wives | −2.99 | 0.86 | −3.47*** | .33 | −17.95 | 12.98 | −1.38 | .14 | 1.30 |

| Tangible | |||||||||

| Husbands | −4.60 | 1.27 | −3.62*** | .34 | −10.87 | 5.17 | −2.10* | .21 | 1.33 |

| Wives | −4.09 | 0.84 | −4.85**** | .43 | −10.44 | 3.08 | −3.39*** | .32 | 4.14* |

Note. Comparisons of the effects of under- vs. overprovision (χ2 tests) were conducted using unstandardized regression coefficients;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .005;

p < .001.

Effect size r = √ [t2 / (t2 + df)].

Figure 1. Summary of Results: Increases in Under- and Overprovision Associated with Declines in Marital Satisfaction.

Underprovision (the extent to which the recipient reported wanting more support) predicting the recipient’s own marital satisfaction Overprovision (the extent to which the recipient reported wanting less support) predicting the recipient’s own marital satisfaction

Next we compared the influences of under- versus overprovision on marital satisfaction. Coefficients for the effects of under- and overprovision on marital satisfaction trajectories differed significantly from one another for husbands (χ2(1) = 4.76, p < .05) and wives (χ2(1) = 5.00, p < .05). Rates of change in overprovision were more strongly associated with changes in marital satisfaction. There were no sex differences in the links between underprovision and marital satisfaction (χ2(1) = 0.06, ns), or overprovision and marital satisfaction (χ2(1) = 1.16, ns).

Aim 3: Do Under- and Overprovision have Unique Implications Depending on Type of Support?

The third aim was to investigate whether the influences of under- versus overprovision on marital satisfaction differed as a function of the type of support being provided. Cross-spouse terms were removed from Level 1 equations due to multicollinearity among the covariates. Given the number of analyses conducted to address Aim 3, only significant results will be discussed; please refer to Table 1 for the full set of results. All significant results followed the same pattern across types of support such that increasing underprovision over time (as reported by support recipients) was associated with greater declines in support recipients’ own marital satisfaction, and increasing overprovision over time was associated with greater marital decline. See Figure 1 for a summary of the results.

Husbands

Rates of change in underprovision were significantly associated with rates of change in marital satisfaction for emotional (t(101) = −3.29, p < .005), esteem (t(101) = −5.04, p < .001), and tangible (t(101) = −3.62, p < .005) support, but not for informational support. Changes in overprovision were significantly associated with changes in marital satisfaction for informational (t(101) = −2.67, p < .01), emotional (t(101) = −2.53, p < .05), and tangible (t(101) = −2.10, p < .05) support, but not for esteem support. Overprovision of informational support was more strongly associated with marital satisfaction than underprovision of informational support (χ2(1) = 5.03, p < .05); however, under- and overprovision did not differ in strength of association with marital satisfaction for emotional (χ2 (1) = 1.78, ns), esteem (χ2 (1) = 0.07, ns), or tangible (χ2(1) = 1.33, ns) support.

Wives

Rates of change in underprovision were significantly associated with rates of change in marital satisfaction for informational (t(101) = −3.83, p < .001), emotional (t(101) = − 5.73, p < .001), esteem (t(101) = −3.47, p < .005), and tangible (t(101) = −4.85, p < .001) support. Changes in overprovision were significantly associated with changes in marital satisfaction for informational (t(101) = −3.64, p < .005), emotional (t(101) = −5.01, p < .001), and tangible (t(101) = −3.39, p < .005) support, but not for esteem support. Overprovision was more strongly associated with marital satisfaction than underprovision for informational (χ2(1) = 4.07, p < .05), emotional (χ2(1) = 11.37, p < .005), and tangible (χ2(1) = 4.13, p < .05) support, but not for esteem support (χ2(1) = 1.30, ns).

Sex differences by type of support

Two sex differences were significant. First, underprovision of informational support was more strongly associated with marital satisfaction for wives than for husbands (χ2(1) = 4.72, p < .05). Second, underprovision of esteem support was more strongly associated with marital satisfaction for husbands than for wives (χ2(1) = 5.21, p < .05). There were no other sex differences in associations between underprovision of types of support and marital satisfaction (χ2s ranged from .16 to 1.10, all ns), or between overprovision of types of support and marital satisfaction (χ2s ranged from .01 to 3.49, all ns).

Discussion

An implicit assumption guiding research on the role of inadequate support in marriage is that inadequate support is a unitary, continuous construct. The purpose of the present study was to challenge this assumption and, more generally, to establish whether the separate examination of each form of inadequate support - support underprovision (not receiving enough support) and support overprovision (receiving too much support) - contributes to a more accurate and refined conceptualization of support in marriage. This study is the first to separately examine under- and overprovision of support, and the first to identify the distinct contributions of each to marital satisfaction. All variables were assessed at five time points and over five years of marriage, which allowed us to examine the dynamic nature of multiple support processes. Hypotheses were analyzed using APIM and growth curve analytic techniques, which allowed us to address within- and between-subject questions and interdependence between husbands and wives.

Summary and Interpretation of Results

Results of the present study support our contention that under- and overprovision of partner support are qualitatively distinct constructs that should be examined separately in marital research. First, an examination of the unique characteristics of under- and overprovision revealed that operationalizing inadequate support as a unitary construct provides a limited perspective of support processes in newlywed marriage. Under- and overprovision occurred at different rates, demonstrated different developmental trajectories over the first five years of marriage, and were only weakly correlated with one another. Second, each form of inadequate support was associated with marital decline, but the results of Aim 2 revealed that overprovision was a stronger risk factor for marital decline than underprovision. Consistent with our hypotheses, individuals experienced greater marital decline to the extent that their reports of underprovision and overprovision increased (or at least remained stable rather than declining) over time. However, although couples reported more underprovision than overprovision of support, overprovision was more strongly associated with marital decline for both husbands and wives.

Third, when we examined the relative influences of under- versus overprovision of support from a multidimensional perspective, we found that the implications for marriage depend to some extent on the type of support being provided inadequately (informational, emotional, esteem, or tangible). Although underprovision was generally associated with marital decline for both spouses, underprovision of informational support was not associated with husbands’ marital satisfaction. Similarly, overprovision was also generally associated with marital decline for both spouses; however, overprovision of esteem support was not associated with husbands’ or wives’ satisfaction. Additionally, although overprovision of support generally appeared to be a greater risk factor for marital decline than underprovision (when collapsing across support types), employing a multidimensional perspective yielded further clarification of this finding. Under- and overprovision of esteem support did not differentially predict marital decline. Further, for husbands, only overprovision of informational support emerged as a greater risk factor for marital decline (compared to underprovision). In sum, receiving more informational, emotional, and tangible support than is desired is especially detrimental for wives’ marital satisfaction, whereas receiving more informational support than is desired is particularly problematic for husbands. Finally, with regard to sex differences, underprovision of informational support was a greater risk factor for wives’ marital decline than for husbands’, whereas underprovision of esteem support was a greater risk factor for husbands’ marital decline than for wives’. There were no sex differences for the effects of overprovision on marital satisfaction.

Before we turn to the implications of the present study, we note several methodological limitations. First, although the sample size was comparable to many published studies of newlyweds, replication of these findings with a larger sample is recommended. For example, to address Aim 3, we did not have the power to include underprovision and overprovision of all four types of support within and across spouses as simultaneous predictors (which would have comprised 39 predictors/covariates). Second, the sample consisted primarily of Caucasian, fairly well-educated couples, and all couples were married and heterosexual; such demographic factors limit our ability to generalize out findings to the consequences of underprovision and overprovision of support for dating or cohabiting couples, ethnic minorities, or same-sex couples, for example. Third, given that the study was not experimental, causal conclusions cannot be drawn. Further, our analytic approach speaks to covariation rather than temporal or causal relations. Thus, we cannot state for certain whether under- or overprovision precede or result from marital discord. Fourth, our reliance on self-report measures introduces the limitation of shared methods; however, given the nature of the constructs examined in this study (spouses’ perceptions of support adequacy and marital satisfaction), methods other than self-report (e.g., behavioral observations during support interactions) would have been inappropriate. Fifth, although couples participating in this study were in the early years of marriage, they were not necessarily in new relationships at the start of the study. Couples reported dating an average of 44 months prior to marriage and 76% of them cohabitated premaritally. Finally, on average, the sample was generally maritally satisfied. It seems likely that the findings might differ in a sample of distressed, treatment-seeking couples or couples in established marriages.

Theoretical, Empirical, and Clinical Implications of the Present Study

Based on the results of the present study, we suggest that the basic premise of optimal matching theory (Cutrona, 1990; Cutrona & Russell, 1990) – that support should match the circumstances being faced by a given individual in order to be optimal – be interpreted in a broader sense such that: (a) the match between support and the unique preferences of a support recipient is emphasized; (b) a “mismatch” is conceptualized as occurring in the form of under- or overprovision of support; (c) under- and overprovision are viewed as qualitatively distinct constructs; (d) receiving “too much” support (overprovision) is recognized as being potentially worse than receiving “too little” support (underprovision); and (e) under- and overprovision are conceptualized as having unique implications for marriage depending on the type of support being provided inadequately. Within this conceptual framework, an entirely new area of research can be pursued in order to delineate the role of support processes in the developmental course of marriage and to identify how to best help individuals form healthy and rewarding relationships.

More generally, we call for marital researchers to examine under- and overprovision of support as qualitatively distinct factors contributing to marital discord. The implicit assumption that support inadequacy is a unitary, continuous construct – an assumption that has guided prior research on support inadequacy in marriage – does not appear to be valid; rather, inadequate support can be differentiated into two distinct forms of support inadequacy – under- and overprovision – that, when examined separately, provide novel information about the nature of partner support in marriage. This assumption has resulted in researchers overlooking the consequences of receiving too much support (overprovision) relative to not receiving enough support (underprovision). Indeed, results of the present study suggest that the provision of unwanted support may be a greater risk factor for marital decline than receiving infrequent support. Moreover, we have presented multiple theories (i.e., stress and coping, equity, and reactance) for conceptualizing under- and overprovision of partner support. The next step is for researchers to examine each form of inadequate support within these frameworks in order to develop novel theories delineating the roles of under- and overprovision in marriage. For example, under- and overprovision might be examined within a stress and coping framework in order to determine how inadequate support interferes with coping efforts to influence marriage.

In addition to examining under- and overprovision as qualitatively distinct forms of inadequate support, we recommend that researchers examine under- and overprovision from a multidimensional perspective. Although we hypothesized that overprovision of action-facilitating support (i.e., informational and tangible support) would be especially detrimental to marriage given the potential for psychological reactance, results did not support this prediction. Categorizing support types as action-facilitating versus nurturant appears to have little utility within the context of research on under- and overprovision of support. Rather, examining each of four specific support types (i.e., informational, emotional, esteem, and tangible) appears more informative. In sum, examining under- and overprovision of support from a multidimensional perspective provides a more detailed understanding of the specific support behaviors posing the greatest risk for marital discord when provided inadequately.

Results of the present study suggest novel directions for basic research. First, researchers might examine the unique mechanisms through which under- and overprovision contribute to marital discord. Toward this goal, we offer several hypotheses for consideration. For example, within a stress and coping framework, underprovision might result in support recipients not receiving the necessary resources for effectively coping with a problem, which in turn may leave recipients dissatisfied with their marital relationships. Conversely, overprovision might fosters feelings of guilt for not using support that is ineffective for coping, which in turn interferes with one’s coping efforts and leads to marital dysfunction. Finally, consistent with reactance theory (Brehm, 1966), overprovision might foster psychological reactance when support is viewed as patronizing, which in turn might contribute to negative feelings or aggression toward one’s spouse.

Second, we call for researchers to identify intervening variables that might buffer or exacerbate the negative effects of under-and overprovision on marriage. In the present study, the effects of under- and overprovision on marital satisfaction depended on the type of support provided inadequately. Additional factors such as degree of stress experienced by support recipients or the quality of other aspects of the marital relationship (e.g., emotional intimacy, conflict management skills) may interact with the effects of under- and overprovision on marital satisfaction. Indeed, we expect support to interact with other marital processes – both positive (e.g., intimacy) and negative (e.g., conflict) – to contribute to marital satisfaction.

Third, we recommend that researchers identify the different factors predicting the courses of under- and overprovision of support. Risk factors that contribute to under- or overprovision might include characteristics of the support recipient (e.g., personality traits such as dependency), characteristics of the support provider (e.g., dispositional empathy), contextual factors (e.g., socioeconomic status, stressors external to the relationship), or dynamics of the relationship (e.g., emotional disengagement). Further, consistent with equity theory (Walster et al.), researchers might examine whether inequity between support that a spouse provides versus support received in return predicts subsequent under- or overprovision of support.

From a clinical standpoint, overprovision appears to be an important risk factor to consider when preparing couples for newlywed marriage. Couples preparing for marriage or who are newly married should be educated about the possibility of providing “too much support” to their spouses, trained to effectively communicate the amount and type of support that they desire during support exchanges, and taught to respectfully provide their spouses with feedback in order to enhance the quality of future support transactions. Further, given that overprovision of esteem support was not significantly associated with marital decline, we recommend educating partners about how providing esteem support may be a good option if they are unsure about what their spouses desire in a given situation. In contrast, couples may be warned about providing informational support if they are uncertain about their spouse’s support needs.

Helping couples to optimize support in their marriages may be the key to enhancing the efficacy of marital preparation programs. To date, implementing a support skills component with more traditional problem-solving skills training has failed to produce more efficacious interventions for preventing marital discord and divorce (Rogge et al., 2002). Indeed, given that overprovision may actually be a greater risk factor for marital decline than underprovision, interventions encouraging more frequent support may actually be contraindicated. Existing marital preparation programs may be improved by recognizing that enhancing the frequency of support provided in marriage is insufficient and that educating couples about the potential for overprovision– in particular with regard to certain types of support -- may be necessary.

Acknowledgments

Although data from this sample have been published elsewhere (e.g., Brock & Lawrence, 2008), this is the first article in which the support adequacy data were examined across multiple time points, and the first article in which underprovision and overprovision data were examined separately. Portions of this article were presented at the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies Convention, November, 2008. Collection and analyses of these data were supported by research grants from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CE721682 and CCR721682, the National Institute for Child and Human Development HD046789, and The University of Iowa (to Erika Lawrence).

We thank Robin A. Barry, Mali Bunde, Amie Langer, Eunyoe Ro, Jeung Eun Yoon, Erin Adams, Ashley Anderson, Katie Barnett, Sara Boeding, Jill Buchheit, Jodi Dey, Christina E. Dowd, Sandra Dzankovic, Katherine Conlon Fasselius, Emily Fazio, Emily Georgia, Dailah Hall, Emma Heetland, Deb Moore-Henecke, David Hoak, Matthew Kishinami, Jordan Koster, Lisa Madsen, Lorin Mulryan, Ashley Pederson, Luke Peterson, Polly Peterson, Ashley Rink, Heidi Schwab, Jodi Siebrecht, Abby Waltz, Shaun Wilkinson, and Nai-Jiin Yang for their assistance with data collection.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/journals/fam.

In the general social support literature, researchers have examined two facets of support quantity: enacted support and received support. Enacted support refers to overt support behaviors provided during a supportive interaction, and is assessed through videotaped interaction tasks involving objective ratings of support provision (e.g., Lawrence et al., 2008). In contrast, received support refers to support behaviors perceived by a support recipient as being provided during a support transaction (Pierce, Sarason, Sarason, & Henderson, 1996). Members of one’s support network may enact support behaviors, but the intended recipient may not notice the behaviors or perceive them as supportive (Pierce et al., 1996). Indeed, research has demonstrated low to moderate agreement between ratings of enacted and received support (Sarason et al., 1990). Many researchers argue that, for support to be beneficial, behaviors must not only be enacted but must also be received (e.g., Pierce et al.). Accordingly, researchers are increasingly focusing on received support, and have found that higher levels of received support are associated with greater marital satisfaction (e.g., Abbey, Andrews, & Halman, 1995).

Network support was excluded from our analyses due to low internal consistency. Please see the Method section for details. Poor reliability of network support is consistent with a recent study by Cutrona and colleagues in which network support was also omitted from analyses due to low reliability.

Contributor Information

Rebecca L. Brock, Department of Psychology, The University of Iowa

Erika Lawrence, Department of Psychology, The University of Iowa..

References

- Abbey A, Andrews FM, Halman LJ. Provision and receipt of social support and disregard: What is their impact on the marital life quality of infertile and fertile couples? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;68:455–469. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.68.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry R, Bunde M, Brock R, Lawrence E. Validity and utility of a multi-dimensionalmodel of received support in relationships. Journal of Family Psychology. doi: 10.1037/a0014174. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach SR, Martin JK, Blum TC, Roman PM. Effects of marital and co-worker relationships on negative affect: Testing the central role of marriage. American Journal of Family Therapy. 1993;21:313–323. [Google Scholar]

- Beach S, Fincham FD, Katz J, Bradbury TN. Social support in marriage: A cognitive perspective. In: Pierce GR, Sarason BR, Sarason IG, editors. Handbook of social support and the family. NY: Plenum; 1996. pp. 43–65. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury T, Fincham F, Beach S. Research on the nature and determinants of marital satisfaction: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62:964–980. [Google Scholar]

- Brehm JW. A psychological theory of reactance. NY: Academic Press; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Brock RL, Lawrence E. A longitudinal investigation of stress spillover in marriage: Does spousal support adequacy buffer the effects? Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:11–20. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC, DeLongis A. Going beyond social support: The role of social relationships in adaptation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1986;54:454–460. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.4.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE. Stress and social support: In search of optimal matching. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1990;9:3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE. Social support in couples. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Cohen B, Igram S. Contextual determinants of the perceived support-iveness of helping behaviors. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1990;7:553–562. [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Hessling RM, Suhr JA. The influence of husband and wife personality on marital social support interactions. Personal Relationships. 1997;4:379–393. [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Russell DW. Type of social support and specific stress: Toward a theory of optimal matching. In: Sarason BR, Sarason IG, Pierce GR, editors. Social support: An interactional view. England: Wiley; 1990. pp. 319–366. [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Shaffer PA, Wesner KA, Gardner KA. Optimally matching support and perceived spousal sensitivity. Journal of Family. 2007;21:754–758. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Suhr JA. Controllability of stressful events and satisfaction with spouse support behaviors. Communication Research. 1992;19:154–174. [Google Scholar]

- Dehle C, Larsen D, Landers JE. Social support in marriage. American Journal of Family Therapy. 2001;29:307–324. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Bradbury TN. Social support in marriage: The role of social cognition. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1990;9:31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Linfield KJ. A new look at marital quality: Can spouses feel positive and negative about their marriage? Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;11:489–502. [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN. The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, methods, and research. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118:3–34. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic data analysis. NY: Guilford; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence E, Bunde M, Barry R, Brock RL, Sullivan KT, Pasch LA, White GA, Dowd CA, Adams EE. Partner support and marital satisfaction: Support amount, adequacy, provision and solicitation. Personal Relationships. 2008;15:445–463. [Google Scholar]

- Lefcourt HM, Martin RA, Saleh WE. Locus of control and social support: Interactive moderators of stress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984;47:378–389. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD. Social support and personal characteristics: A developmental and interactional perspective. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1990;9:54–68. [Google Scholar]

- Norton R. Measuring marital quality: A critical look at the dependent variable. Journa of Marriage and the Family. 1983;45:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce GR, Sarason BR, Sarason IG, Henderson CA. Conceptualizing and assessing social support in context of the family. In: Pierce GR, Sarason BR, Sarason IG, editors. Handbook of social support and the family. NY: Plenum; 1996. pp. 2–23. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear modeling: Applications and data analysis methods (Advanced quantitative technology in the social sciences) CA: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rogge R, Cobb R, Johnson M, Lawrence E, Bradbury TN. The CARE Program: A preventive approach to marital intervention. In: Jacobson NS, Gurman AS, editors. Clinical handbook of couple therapy. 3rd ed. NY: Guilford; 2002. pp. 420–440. [Google Scholar]

- Sarason BR, Sarason IG, Pierce GP. Traditional views of social support and their impact on assessment. In: Sarason BR, Sarason IG, Pierce GP, editors. Social support: An interactional view. NY: Wiley; 1990. pp. 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Stress, coping, and social support processes: Where are we? What next? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;35:53–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walster E, Berscheid E, Walster GW. New direction in equity research. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1973;25:151–176. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]