Abstract

Objective:

Obesity is associated with higher health-care costs due, in part, to higher use of traditional health care. Few data are available on the relationship between obesity and the use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM).

Methods and Procedures:

We analyzed data on CAM use from the 2002 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) Alternative Medicine Supplement (n = 31,044). We compared the use of CAM overall, within the past 12 months, between normal weight (BMI from 18 to <25), overweight (from 25 to <30), mildly obese (from 30 to <35), moderately obese (from 35 to <40), and extremely obese (>40) adults. For the primary analysis, our multivariable model was adjusted for sociodemographic factors, insurance status, medical conditions, and health behaviors. We performed additional analyses to explore the association of BMI and the use of seven CAM modalities.

Results:

We found that adults with obesity have lower prevalence of use of yoga therapy, and similar prevalence of use of several CAM modalities, including relaxation techniques, natural herbs, massage, chiropractic medicine, tai chi, and acupuncture, compared to normal-weight individuals. After adjustment for sociodemographic factors, insurance status, medical conditions, and health behaviors, adults with obesity were generally less likely to use most individual CAM modalities, although the magnitude of these differences were quite modest in many cases.

Discussion:

Even though adults with obesity have a greater illness burden and higher utilization of traditional medical care, adults with higher BMIs were no more likely to use each of the individual CAM therapies studied. Additional research is needed to improve our understanding of CAM use by adults with obesity.

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is associated with higher health-care costs and use of conventional medical care overall (1-7). Effective conventional medical treatments for obesity are limited, and evidence suggests that patients with obesity are seeking alternative forms of health care for weight loss. One multistate telephone survey found that 16% of women and 6% of men with obesity used a nonprescription weight loss product over a 2-year time period (8).

Furthermore, use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) (9) has been associated with medical conditions linked to obesity (10), and emerging evidence suggests that some CAM therapies may be effective in managing obesity-related conditions, such as osteoarthritis and low back pain (2,9,11-15). Thus, patients with obesity may also be using CAM to treat their comorbid conditions.

While several previous studies have examined patterns of CAM use in different populations (16-21), limited data are available on the relationship between obesity and the use of CAM. Characterization of CAM use by bodyweight may facilitate more accurate estimation of the health care and utilization attributable to obesity, as these estimates have often not accounted for CAM use associated with obesity. Examining patterns of use may also guide areas of future research.

In this context, we examined whether higher BMI was associated with higher use of CAM in the US population. We also explored differences in the motivations for using CAM and in the disclosure rates of CAM use to medical providers by weight category.

METHODS AND PROCEDURES

Data source

The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) is an in-person household survey of the civilian, noninstitutionalized, US population conducted by the Census Bureau for the National Center for Health Statistics and the Centers for Disease Prevention and Control. The basic module of the NHIS consists of three components: the Family Core, the Sample Adult Core, and the Sample Child Core. The Family Core collects information on sociodemographic characteristics, health status, insurance status, and access to and use of health-care services for each family member. One adult, ≥18 years, is randomly selected for administration of the Sample Adult Core questionnaire, which elicits information about height, weight, common medical conditions, and health-care utilization. In 2002, adults selected for the Adult Core were also administered the Alternative Medicine Supplement, which queried respondents about the use of 18 complementary and alternative therapies (9). Respondents were asked, “During the past 12 months, have you used (specific therapy)?” In 2002, 31,044 adults from 36,831 families participated in the Sample Adult component, representing a 74.3% response rate (22).

Outcomes of interest

We defined our primary outcome as the use of one or more complementary and alternative therapies within the past 12 months (yes/no), excluding prayer. We also examined the use of the most prevalent modalities, which included: herbs; relaxation techniques (meditation, progressive muscle relaxation, deep breathing exercises, and guided imagery); massage therapy; chiropractic; yoga; tai chi; and acupuncture. We compared persons who used an individual CAM therapy with those who had not used any CAM therapy within the past 12 months.

In addition, we examined the relationship between obesity and the following secondary outcomes: (i) disclosure of use of CAM to conventional medical providers; (ii) respondents' rating of the importance of CAM for maintaining health and well-being (very important, somewhat important, a little important, not at all important); and (iii) whether CAM was used to treat specific medical conditions. We also examined the respondents' answers (yes/no) to several questions exploring the motivations for CAM use to treat specific medical conditions, which included the following: conventional treatments would not help; conventional treatments were too expensive; conventional medical provider suggested it; would be interesting to try; and combined with conventional medical therapies would be helpful.

BMI

We used BMI as our primary measure of obesity, defined as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. BMI was calculated from self-reported data on height and weight. We categorized respondents into nationally defined weight categories: (i) normal weight (18.5 to <25kg/m2); (ii) overweight (25.0 to <30kg/m2); (iii) mildly obese (30 to <35kg/m2); (iv) moderately obese (35 to <40kg/m2); and (v) extremely obese (≥40kg/m2) (23). We excluded the 582 under-weight respondents with a BMI under 18.5 since this was a small and likely clinically heterogeneous group. Sample sizes for yoga, tai chi, and acupuncture were small, and therefore for these therapies we regrouped respondents in the two or three highest BMI categories into a single category to obtain samples sufficient for analyses (i.e., n > 50).

Additional factors of interest

We considered several potential confounders known to be associated with obesity or with CAM use. These included sociodemographic characteristics, health-care access, illness burden, and health habits (24-26). We considered sociodemographic characteristics such as age, sex, race, marital status, educational attainment, household income, region of residence, and place of birth. We defined health-care access using several proxies including: type of insurance (uninsured, Medicare, Medicaid, private Health Maintenance Organization, private fee for service); usual source of care (primary care provider, obstetrician–gynecologist, specialist, no provider, but usual source of care, no usual source of care and no provider or usual source of care); and number of visits to health-care providers per year (0, 1, 2–3, 4–5, 6–7, 8–9, 10–12, 13–15, ≥16). We used several indicators to capture respondents' illness burden, including medical conditions associated with CAM use, number of hospitalizations in the past year (none, one, two or more), and mobility status (no impairment, minor, moderate, severe impairment) (27). We considered 30 of the 63 medical conditions available in the NHIS to be potentially correlated with use of any CAM therapy, including conditions of the cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, rheumatologic, neurologic, and genitourinary systems, cancer, psychiatric, and infectious diseases, and chronic pain syndromes. As a measure of respondents' health behavior, we used data on smoking status (current, former, never) and physical activity (vigorous activity ≥2 times/week or moderate activity ≥4 times/week), moderate (vigorous activity 1 time/week or moderate activity 1–3 times/week), or sedentary (no vigorous or moderate activity/week) based on validated methods described previously (28).

Statistical analyses

We performed bivariable analyses to compare respondent characteristics by BMI categories. We used χ2-tests for categorical factors and Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney tests for ordinal variables (e.g., number of visits to a doctor).

To explore the relationship between BMI and overall CAM use, we developed a series of multivariable logistic regression models, and then created separate models for each individual CAM modality. First, we adjusted for age and sex, and then we additionally adjusted for other sociodemographic factors (race, income, education, marital status, region of residence, place of birth), insurance status, medical conditions associated with CAM use, and health habits. We then created separate models for individual CAM modality, adjusting for sociodemographic factors, insurance status, medical conditions associated with use of the particular therapy, and health behaviors. We report P values for trend for the adjusted associations between BMI and use of any CAM therapy and use of individual therapies. Because earlier studies have suggested that the relationship between BMI and health-care utilization might vary by race (29,30), we also stratified our primary analysis by race/ethnicity.

Since few previous studies have examined the relationship between CAM use and chronic medical conditions, we developed multivariable logistic regression models to identify medical conditions associated with CAM use within the past 12 months in this sample. Conditions with a P < 0.15 on bivariable analyses were considered for inclusion in the models adjusted for sociodemographic factors and insurance status. Only conditions with a Wald statistic P ≤ 0.05 were retained in the final models. We repeated this analysis for each individual CAM modality to identify medical conditions associated with use of that particular therapy.

To examine the robustness of our results, we further adjusted for additional proxies of health-care access (number of visits to health-care provider and usual source of care), and then adjusted for additional health status variables (number of hospitalizations and mobility status).

We used χ2-tests to explore differences in the prevalence of respondents' disclosure of CAM use to conventional medical providers, respondents' rating of the importance of CAM for maintaining health and well-being, and CAM use for treatment of specific medical conditions by BMI category. In addition, we compared the motivations for using CAM to treat specific medical conditions by BMI category. Sample size permitting, we explored these secondary outcomes by individual CAM therapy, and then combined data across all CAM therapies.

All analyses were performed using SAS-callable SUDAAN version 9.0 (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC) to account for the complex sampling design, and results were weighted to reflect national estimates.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics and health habits of respondents by BMI category. Overall, 58% of adults in our sample were overweight or obese. The majority of respondents were white, married, had private health insurance, and were born in the United States. Women comprised a higher proportion of normal weight and moderately to extremely obese adults.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics and health habits of sample adults by BMI categorya

| Overall sample |

Normal weight |

Overweight | Mild obesity |

Moderate–extreme obesity |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | 18.5 to <25 | 25 to <30 | 30 to <35 | ≥ 35 | |

| Sample size | 31,044 | 11,513 | 10,249 | 4,564 | 1,581 |

| Estimated populationb | 205,825,095 | 77,221,979 | 68,657,089 | 29,935,627 | 10,208,474 |

| Population % | 40 | 35 | 15 | 5 | |

| Age (years) mean (s.e.) | 43 (0.003) | 46 (0.003) | 47(0.014) | 46 (0.013) | |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 50 | 61 | 40 | 44 | 60 |

| Race | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 73 | 76 | 73 | 71 | 67 |

| Hispanic | 11 | 9 | 12 | 11 | 11 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 11 | 9 | 11 | 15 | 21 |

| Education | |||||

| High school graduate | 30 | 28 | 30 | 32 | 35 |

| College graduate | 24 | 28 | 26 | 20 | 14 |

| Income | |||||

| <$20,000 | 19 | 20 | 17 | 20 | 23 |

| $20,000–$35,000 | 30 | 30 | 29 | 30 | 28 |

| $35,000–$65,000 | 23 | 22 | 24 | 23 | 26 |

| > $65,000 | 27 | 28 | 30 | 27 | 22 |

| Insurance | |||||

| Uninsured | 16 | 16 | 14 | 16 | 15 |

| Medicare | 17 | 16 | 18 | 17 | 16 |

| Medicaid | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 8 |

| Private, HMOc | 27 | 23 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| Private, fee for service | 28 | 28 | 30 | 27 | 25 |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Never | 54 | 56 | 53 | 52 | 53 |

| Former | 22 | 19 | 25 | 27 | 27 |

| Current | 22 | 25 | 22 | 21 | 19 |

| Physical activity leveld | |||||

| Sedentary | 39 | 36 | 38 | 42 | 50 |

| Moderate | 22 | 22 | 23 | 23 | 21 |

| Vigorous | 38 | 41 | 39 | 35 | 28 |

NHIS, National Health Interview Survey.

Weighted population percent.

NHIS complex sampling scheme allows for weighted estimates of US population.

HMO, Health Maintenance Organization.

Physical activity levels: vigorous, vigorous activity two times per week or moderate activity four times per week; moderate, vigorous activity one time per week or moderate activity one to three times per week; sedentary, no vigorous or moderate activity per week.

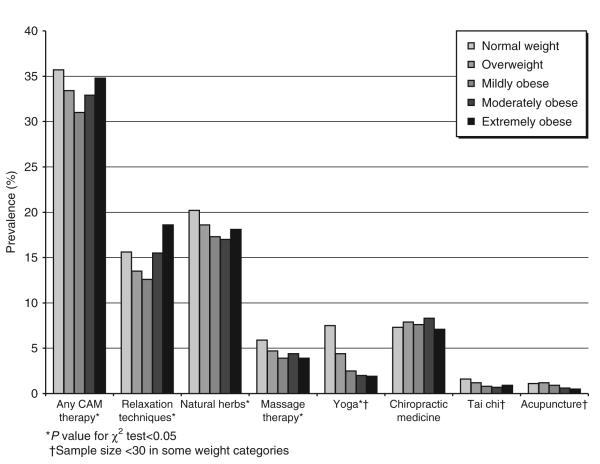

Figure 1 illustrates the prevalence of CAM use by BMI category. Approximately 36% of respondents used any CAM therapy within the past 12 months. While use of CAM overall was lowest among adults with mild obesity, patterns of use varied for the individual CAM modalities. Relaxation techniques displayed a trend similar to use of any CAM therapy, while use of herbs, massage therapy, and yoga was less prevalent in adults with obesity. Except for yoga, observed differences by BMI were modest. Use of chiropractic, tai chi, and acupuncture did not differ by weight category.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of use of complementary and alternative medicine by weight category.

Table 2 presents the adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the associations between use of CAM and BMI category. Higher BMI was associated with lower likelihood use of any CAM use. We observed a similar trend of lower use with higher BMI for all CAM modalities, except for chiropractic medicine. However, many of these associations were modest. When we stratified use of any CAM by race/ethnicity, results appeared similar.

Table 2.

Adjusted odds ratios (95% CI) between weight category and use of complementary and alternative medical therapiesa

| BMI category | Any CAM therapy |

Relaxation | Natural herbs |

Massage | Yoga | Chiropractic | Tai chi | Acupuncture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal weight | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Overweight | 0.98 (0.91, 1.06) |

0.95 (0.86, 1.04) |

0.98 (0.89, 1.07) |

0.93 (0.77, 1.10) |

0.84 (0.72, 0.99) |

1.07 (0.93, 1.22) |

0.83 (0.64, 1.09) |

1.02 (0.75, 1.39) |

| Mildly obese | 0.84 (0.76, 0.93) |

0.76 (0.66, 0.88) |

0.87 (0.77, 0.98) |

0.75 (0.59, 0.96) |

0.49 (0.36, 0.59) |

0.97 (0.82, 1.15) |

0.59 (0.41, 0.85)b |

0.56 (0.36, 0.86)b |

| Moderately obese |

0.86 (0.74, 1.01) |

0.91 (0.74, 1.13) |

0.85 (0.70, 1.03) |

0.85 (0.59, 1.23) |

0.35 (0.24, 0.50)c |

0.94 (0.71, 1.24) |

d | d |

| Extremely obese | 0.82 (0.67, 1.00) |

0.86 (0.66, 1.12) |

0.84 (0.65, 1.09) |

0.71 (0.45, 1.13) |

d | 0.87 (0.63, 1.20) |

d | d |

| P value for trend | <0.0001 | <0.001 | <0.05 | <0.005 | <0.0001 | 0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

CAM, complementary and alternative medicine; CI, confdence intervals.

Adjusted for sociodemographic factors, insurance status, health habits, and medical conditions associated with use of any CAMe or individual CAM therapy.

Represents collapsed mild, moderate, and extreme obesity categories.

Represents collapsed moderate and extreme obesity categories.

Sample size <30, estimate unreliable.

Medical conditions associated with use of any CAM: history of: recurring pain >12 months, insomnia, diabetes, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, urinary problems, bowel disease, thyroid disease; diagnosed within past 12 months: anxiety/depression, sinusitis; diagnosed within the past 3 months: low back pain, joint symptoms >3 months, neck pain, headache.

Overall, only 25% of adults who used any CAM therapy in our sample disclosed their use to a conventional medical provider. When we examined whether obesity was associated with disclosure of any CAM use, and disclosure of use of relaxation techniques and herbs specifically, we found that adults with obesity had slightly higher rates of disclosure to conventional medical providers. For any CAM use, disclosure rates were 26% for overweight adults and 29–34% for adults with obesity compared to 22% for normal-weight adults. For use of relaxation techniques, disclosure rates were 24% for overweight adults and 25-29% for adults with obesity compared to 21% for normal-weight adults, and for natural herb use, disclosure rates were 33% for overweight adults and 38–42% for adults with obesity compared to 30% for normal-weight adults (all P ≤ 0.01).

In our sample, 40% of adults used CAM for treatment of a specific medical condition, and adults with obesity had slightly higher rates of use. Forty-two percent (42%) of over-weight adults and 45–50% for adults with obesity, compared to 35% for normal-weight adults, used any CAM therapy to treat a specific medical condition (P < 0.001). More specifically, 31% of overweight adults and 39–40% of adults with obesity, compared to 27% of normal-weight adults used relaxation techniques to treat a specific condition (P < 0.001). Figure 2 depicts the rationale by adults using CAM to treat a specific medical condition by weight category. Adults who were over-weight and obese were slightly more likely to use CAM in combination with conventional medical therapies and because a conventional provider suggested it. No significant differences by weight categories were found for other motivations for CAM use. In addition, no differences in respondents' ratings of the importance of CAM use in maintaining health and well-being (very important: 43–47% vs. 40%; somewhat important: 31–38% vs. 33%; not at all important: 19–24% vs. 24%; all P > 0.05) were detected by weight category.

Figure 2.

Among adults using complementary and alternative medicine to treat a specific medical condition (n = 4,122), reasons given for CAM use by weight category.

DISCUSSION

We found that adults with obesity have lower prevalence of use of yoga therapy, and similar prevalence of use of several CAM modalities, including relaxation techniques, natural herbs, massage, chiropractic medicine, tai chi, and acupuncture, compared to normal-weight individuals. After adjustment for sociodemographic factors, insurance status, medical conditions, and health behaviors, adults with obesity were generally less likely to use most individual CAM modalities, although the magnitude of these differences were quite modest in many cases.

Despite the estimated 1.3 billion dollars spent on weight loss supplements in 2001 (31), we found low prevalence of use of natural herbs overall by adults with obesity. These results were surprising given the results of a recently published national survey that found the prevalence of use of nonprescription weight loss supplements to be 8.7% overall, and use by adults with obesity substantially higher than that of normal-weight individuals (32). One potential explanation for our different findings may be the way that supplements were categorized in our study. Because the NHIS grouped use of nonvitamin/nonmineral supplements under the heading of natural herbs, if a respondent did not categorize their weight loss supplement as a natural herb, data would not have been collected on their use of the supplement. Our results also contrast data reported from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) which found that higher BMI is associated with lower use of dietary supplements overall (33). However, NHANES included use of multivitamin/multimineral supplements in their definition of dietary supplements, whereas our study focused specifically on use of natural herbs. Therefore, these differing categorizations limit direct comparisons of the relationship between BMI and dietary supplement use between the surveys.

We had expected adults with obesity to have the same or higher use of CAM given their increased burden of disease and greater use of conventional medical care. One potential explanation for lower use of some CAM therapies, including yoga and massage, by adults with obesity may be related to their reduced participation in healthy lifestyle behaviors. Previous studies have suggested that CAM users are more likely to engage in physical activity (34,35), and our results are consistent with these findings. However, even after we adjusted for physical activity level and smoking status, we found lower use of yoga, massage, tai chi, and acupuncture with higher BMI categories, suggesting that additional factors are influencing the use of these CAM therapies by adults with obesity. Interestingly, among respondents who had used any CAM therapy, we did not detect any difference in the rating of the importance of CAM use for maintaining health and well-being between weight categories.

Our study could not explicitly examine whether respondents were using CAM therapies in place of conventional care. However, in the 40% of adults using CAM to treat a specific medical condition, <50% used CAM in combination with conventional medical care. We found that adults with obesity were slightly more likely to use CAM in combination with conventional care.

We found the strongest relationship between obesity and low use of CAM for yoga therapy. One potential explanation is that most types of yoga are more difficult to perform with a large body habitus, and therefore may create situations of self-doubt, discomfort, and embarrassment (36), discouraging adoption and extended use by adults with obesity. Likewise, slightly lower use of massage therapy by adults with obesity, may reflect avoidance of therapies that require body exposure and manipulation by a provider. Interestingly, use of chiropractic, which also focuses on the body, did not differ by weight category. Further understanding of differences in patterns of use by adults with obesity might help us better understand the particular health-care expectations and needs, as well as the potential barriers to care of this population. Patterns of utilization of CAM by adults with obesity are of particular interest as evidence is emerging on the efficacy of CAM for treatment of some medical conditions related to obesity, such as low back pain and hypertension (9,11,13-15,37-41). However, based upon our results, it does not appear that out-of-pocket expenditures for CAM therapies augment health-care costs attributable to obesity.

Disclosure rates of CAM use to conventional medical providers were somewhat higher among adults with obesity, although overall rates of disclosure were low, ranging from 21 to 34%. This low rate for disclosure is concerning for adults with obesity, since they are somewhat more likely to use CAM in combination with conventional medical treatments, and thus may be at greater risk for potential adverse events, such as drug–herb interactions.

There are several potential limitations of our data. First, the self-reporting methodology of NHIS may have led to error or misclassification. For example, adults with obesity tend to underestimate their weight and hence BMI, thus any differences we found across BMI categories were likely underestimated. Second, given the relative low prevalence of respondents with moderate and extreme obesity, we were likely underpowered to detect differences between obesity categories. In addition, since it is challenging to categorize the vast number of non-conventional therapies used in the United States, it is difficult to capture the true prevalence of use of CAM.

In summary, our study suggests that despite their increased burden of disease, adults with obesity are not using CAM therapies at higher rates than normal-weight individuals. Adults with higher BMIs are less likely to use yoga and somewhat less likely to use most other individual modalities after adjustment for several potential confounders. Further research is needed to improve our understanding of the role of CAM in the treatment of obesity and obesity related conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work was supported by Grant R03-AT002236 from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, National Institutes of Health. S.M.B. is supported by an Institutional National Research Service Award (T32AT00051-06) from National Institutes of Health. C.C.W. was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases (K23 DK02962). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Finkelstein EA, Fiebelkorn IC, Wang G. National medical spending attributable to overweight and obesity: how much, and who's paying? Health Aff (Millwood) 2003:W3-219–226. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w3.219. Suppl Web Exclusives. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clegg DO, Reda DJ, Harris CL, et al. Glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and the two in combination for painful knee osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:795–808. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wee CC, Phillips RS, Legedza AT, et al. Health care expenditures associated with overweight and obesity among US adults: importance of age and race. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:159–165. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.027946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson D, Wolf AM. The medical-care cost burden of obesity. Obes Rev. 2001;2:189–197. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2001.00037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quesenberry CP, Jr, Caan B, Jacobson A. Obesity, health services use, and health care costs among members of a health maintenance organization. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:466–472. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.5.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson D, Edelsberg J, Colditz GA, Bird AP, Oster G. Lifetime health and economic consequences of obesity. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2177–2183. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.18.2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fontaine KR, Bartlett SJ. Access and use of medical care among obese persons. Obes Res. 2000;8:403–406. doi: 10.1038/oby.2000.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blanck HM, Khan LK, Serdula MK. Use of nonprescription weight loss products: results from a multistate survey. JAMA. 2001;286:930–935. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.8.930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trinh KV, Graham N, Gross AR, et al. Acupuncture for neck disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD004870. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004870.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Astin JA. Why patients use alternative medicine: results of a national study. JAMA. 1998;279:1548–1553. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.19.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Astin JA, Shapiro SL, Eisenberg DM, Forys KL. Mind-body medicine: state of the science, implications for practice. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16:131–147. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.16.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marchioli R, Barzi F, Bomba E, et al. Early protection against sudden death by n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids after myocardial infarction: time-course analysis of the results of the Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell'Infarto Miocardico (GISSI)-Prevenzione. Circulation. 2002;105:1897–1903. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000014682.14181.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scharf HP, Mansmann U, Streitberger K, et al. Acupuncture and knee osteoarthritis: a three-armed randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:12–20. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-1-200607040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vas J, Mendez C, Perea-Milla E, et al. Acupuncture as a complementary therapy to the pharmacological treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2004;329:1216. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38238.601447.3A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vas J, Perea-Milla E, Mendez C, Navarro CS, Leon Rubio JM, Brioso M, et al. Efficacy and safety of acupuncture for chronic uncomplicated neck pain: a randomised controlled study. Pain. 2006;126:245–255. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahn AC, Ngo-Metzger Q, Legedza AT, et al. Complementary and alternative medical therapy use among Chinese and Vietnamese Americans: prevalence, associated factors, and effects of patient-clinician communication. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:647–653. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.048496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graham RE, Ahn AC, Davis RB, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medical therapies among racial and ethnic minority adults: results from the 2002 National Health Interview Survey. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97:535–545. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quandt SA, Chen H, Grzywacz JG, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by persons with arthritis: results of the National Health Interview Survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:748–755. doi: 10.1002/art.21443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yeh GY, Davis RB, Phillips RS. Use of complementary therapies in patients with cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:673–680. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeh GY, Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Phillips RS. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among persons with diabetes mellitus: results of a national survey. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1648–1652. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.10.1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buettner C, Kroenke CH, Phillips RS, et al. Correlates of use of different types of complementary and alternative medicine by breast cancer survivors in the nurses' health study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;100:219–227. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9239-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Center for Health Statistics 2002 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) Survey Description document. 2003 ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_ Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHIS/2002/srvydesc.pdf. (Oct 12, 2005) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Executive summary of the clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweigh and obesity in adults. Arch Intern Med. 1998;159:1855–1867. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.17.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, et al. Unconventional medicine in the United States. Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:246–252. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199301283280406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolsko PM, Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, Phillips RS. Insurance coverage, medical conditions, and visits to alternative medicine providers: results of a national survey. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:281–287. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.3.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Adv Data. 2004:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iezzoni LI, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Siebens H. Mobility impairments and use of screening and preventive services. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:955–961. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.6.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kushi LH, Fee RM, Folsom AR. Physical activity and mortality in postmenopausal women. JAMA. 1997;277:1287–1292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wee CC, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Phillips RS. Obesity and breast cancer screening. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:324–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30354.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wee CC, Phillips RS, McCarthy EP. BMI and cervical cancer screening among white, African-American, and Hispanic women in the United States. Obes Res. 2005;7:1275–1280. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saper RB, Eisenberg DM, Phillips RS. Common dietary supplements for weight loss. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70:1731–1738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blanck HM, Serdula MK, Gillespie C, et al. Use of nonprescription dietary supplements for weight loss is common among Americans. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:441–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Radimer KL, Subar AF, Thompson FE. Nonvitamin, nonmineral dietary supplements: issues and findings from NHANES III. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000;100:447–454. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00137-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bair YA, Gold EB, Greendale GA, et al. Ethnic differences in use of complementary and alternative medicine at midlife: longitudinal results from SWAN participants. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1832–1840. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.11.1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee MM, Lin SS, Wrensch MR, Adler SR, Eisenberg D. Alternative therapies used by women with breast cancer in four ethnic populations. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:42–47. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Puhl R, Brownell KD. Bias, discrimination, and obesity. Obes Res. 2001;9:788–805. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Young DR, Appel LJ, Jee S, Miller ER., 3rd. The effects of aerobic exercise and T'ai Chi on blood pressure in older people: results of a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:277–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb02989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schneider RH, Alexander CN, Staggers F, et al. A randomized controlled trial of stress reduction in African Americans treated for hypertension for over one year. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18:88–98. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schein MH, Gavish B, Herz M, et al. Treating hypertension with a device that slows and regularises breathing: a randomised, double-blind controlled study. J Hum Hypertens. 2001;15:271–278. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grossman E, Grossman A, Schein MH, Zimlichman R, Gavish B. Breathing-control lowers blood pressure. J Hum Hypertens. 2001;15:263–269. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yeh GY, Wood MJ, Lorell BH, et al. Effects of tai chi mind-body movement therapy on functional status and exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Med. 2004;117:541–548. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]