Abstract

Multi-slice-computed tomography coronary angiography (CTA) provides direct non-invasive anatomic assessment of the coronary arteries allowing for early identification of coronary artery disease (CAD). This information is useful for diagnosis of CAD, particularly the rule out of CAD. In addition, early identification of CAD with CTA may also be useful for risk stratification. The purpose of this review is to provide an overview of the current literature on the prognostic value of CTA and to discuss how the prognostic information obtained with CTA can be used to further integrate the technique into clinical practice. Non-invasive anatomic assessment of plaque burden, location, composition, and remodeling using CTA may provide prognostically relevant information. This information has been shown to be incremental to the Framingham risk score, coronary artery calcium scoring, and myocardial perfusion imaging. Characterization of atherosclerosis non-invasively has the potential to provide important prognostic information enabling a more patient-tailored approach to disease management. Future studies assessing outcome after CTA-based risk adjustments are needed to further understand the value of detailed non-invasive anatomic imaging.

Keywords: Unstable atherosclerotic plaque, computed tomography (CT), coronary artery disease, diagnostic and prognostic application

Introduction

The introduction of multi-slice-computed tomography coronary angiography (CTA) has changed the field of non-invasive imaging. In addition to existing functional imaging techniques assessing myocardial perfusion and wall motion, CTA currently provides direct non-invasive anatomic assessment of the coronary arteries. This allows for detection of coronary artery disease (CAD) at an earlier stage compared to functional imaging,1 which may have important implications for the diagnosis as well as prognosis of CAD. For diagnosis, numerous studies support the use of CTA for rule out of the presence of CAD with a high accuracy.2-8 As a result the technique is increasingly used as a gatekeeper for further diagnostic testing. In addition, data are emerging that early identification of CAD with CTA may be useful for risk stratification. Since the first publications on the prognostic value of CTA in 2007 a number of studies have been published providing further insight into the potential value of non-invasive anatomic imaging for risk stratification.8-21 The purpose of this review is to provide an overview of the literature on the prognostic value of CTA and to discuss how the prognostic information obtained with CTA can be used to further integrate the technique into clinical practice.

Accuracy For Risk Stratification

Shift From Stenosis To Atherosclerosis

Diagnostic accuracy studies assessing the value of CTA have determined its ability to identify the presence or absence of significant stenosis (≥50% luminal narrowing).3,22-26 This threshold is important from a diagnostic point of view, as it can identify a cause for the patient’s complaints as well as a treatment target for revascularization. Furthermore, patients with a significant stenosis on CTA may have worse outcome as compared to patients without significant CAD.14,15,18,20 Indeed, an annualized event rate for the occurrence of all cause mortality and myocardial infarction ranging between approximately 1% and 5%14,15,18,20 has been observed in patients with significant CAD compared to approximately 0-2% in patients without significant CAD. However CTA can further differentiate patients as having non-significant CAD or completely normal coronary arteries. This is important as the presence of non-significant CAD may not necessarily be considered benign.27-29 Indeed, myocardial infarction and unstable angina are frequently caused by lesions deemed to be non-significant prior to the event.30-33 In line with this notion, the presence of non-significant CAD on CTA has been associated with an increased annualized event rates up to 1.5%,14,18,20 compared to a very low annualized event rates of <0.7% in patients with completely normal coronary anatomy.8-10,12-14,18,20,34 Accordingly, classification of patients as having normal anatomy, non-significant CAD, or significant CAD may allow straightforward and reliable risk stratification. However, it is conceivable that the prognostic information may be refined by further characterization of the observed atherosclerosis on segmental or plaque level. Potentially, such analysis may include identification of certain characteristics of lesions that may have a higher likelihood to cause thrombotic occlusion of the vessel and subsequent coronary events.

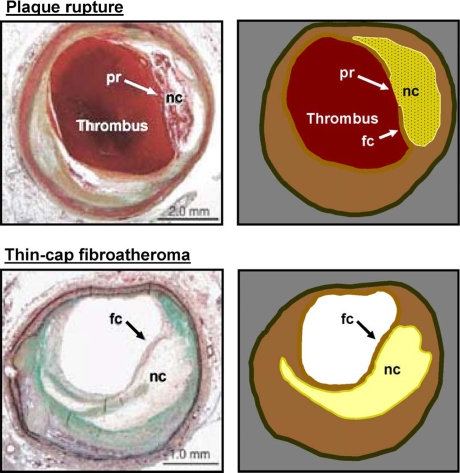

In the past, numerous histological studies have addressed the mechanism underlying coronary occlusion, thereby identifying three major causes, namely plaque erosion, the presence of calcified nodules and, in the majority of cases, plaque rupture.35 In the setting of plaque rupture, the underlying plaque at the site of thrombus formation has been typically characterized as a lesion with a large lipid-rich atheromatous necrotic core, with a ruptured thin fibrous cap and expansive remodeling. These findings have subsequently led to the hypothesis that plaque rupture is caused by rupture of the thin fibrous cap overlying a lesion with a large lipid-rich atheromatous necrotic core (Figure 1). In addition to morphological characteristics of the plaque, the presence of inflammation, as reflected by macrophages and lymphocytes infiltration, also plays an important role. An overview of morphological plaque characteristics associated with vulnerability is provided in Table 1.36 Due to its ability to visualize the vessel wall, CTA may allow non-invasive identification of several characteristics associated with vulnerability including plaque burden, location, composition, and remodeling.37-48

Figure 1.

Thin capped fibroatheroma as a cause of plaque rupture. The top panel shows a histological specimen of a ruptured plaque. As can be observed in the specimen, the lumen is completely occluded by a large thrombus. The underlying plaque contains a large necrotic core (nc) and is covered by a thin fibrous cap (fc) which has ruptured (pr). These findings have subsequently led to the hypothesis that plaque rupture is caused by rupture of the thin fibrous cap of thin capped fibroatheroma plaques. A histological specimen of a thin capped fibroatheroma can be observed in the bottom panel. The plaque is characterized by a large necrotic atheromatous core (similar to the necrotic core observed in sites of plaque rupture), covered by a thin non-ruptured fibrous cap. Adapted and reprinted with permission from Jain et al78

Table 1.

Morphological markers of plaque vulnerability

| Plaque | |

| Plaque cap thickness | |

| Plaque lipid core size | |

| Plaque stenosis | |

| Color | |

| Collagen content versus lipid content, mechanical stability | |

| Calcification burden and pattern | |

| Pan arterial | |

| Total coronary calcium burden | |

| Total arterial burden of plaque including peripheral |

Based on the table from Naghavi et al.36

Non-invasive Characterization of Atherosclerosis with CTA

Plaque burden and location

By combining plaque extent and severity throughout the coronary system, plaque burden can be either assessed quantitatively or semi-quantitatively with CTA by summation of the number of diseased and significantly diseased vessels or segments. Although plaque burden in itself does not directly imply plaque vulnerability, an increase in plaque burden is associated with an increased risk for vulnerable plaques. Several studies have attempted to create models of plaque burden using a modified AHA segment model of the coronary artery tree. In the study by Pundziute et al,8 increased number of segments with plaque as well as increased number of segments with significant stenosis were independent predictors of events when corrected for baseline clinical variables. Using similar scoring methods, other studies have also observed a higher risk for events in patients with increased number of segments with atherosclerosis.10,16 Min et al observed that a segmental involvement score allowed good differentiation between patients with a low and high risk for future events. In patients with more than five segments involved, an absolute event rate of 8.4% was observed compared to 2.5% in patients with a score ≤5.16 In a next step, the extent and severity of atherosclerosis throughout the coronary artery tree was incorporated into the segmental severity score. Each coronary segment was graded according to stenosis severity (absent to severe plaque (0-3)) and the scores for all segments were combined. When using this segmental severity score an absolute event rate of 6.6% was observed in patients with a score >5 compared to 1.6% in patients with a score ≤5.

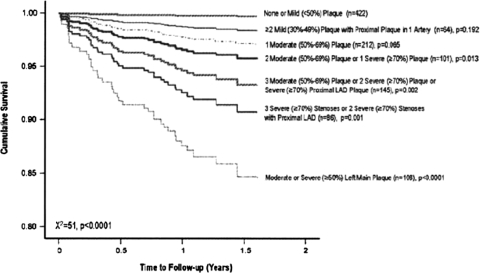

In addition to plaque burden, plaque location should be considered as well, as vulnerable plaques are most often observed in proximal segments of the coronary artery tree.49 The presence of proximal lesions is therefore associated with an increased risk of vulnerable plaques. Furthermore, plaque rupture in a proximal segment also increases the risk of a major cardiac event, due to the larger volume of myocardium that is at risk. Indeed, Pundziute et al8 observed that the presence of left main plaque or proximal LAD plaque was an important independent predictor of events associated with a high event rate. Likewise, in the study by Min et al16 the presence of any left main stenosis was also an independent predictor of events. Subsequently, the authors created a modified version of the Duke coronary artery score by combining both plaque burden and location into a single predictive model. As illustrated in Figure 2, events rates paralleled increasing disease severity as determined with this hierarchic model.

Figure 2.

Prognostic value of CTA. Cumulative survival curves illustrating the risk of events in each category of the Duke Prognostic Coronary Artery Disease Index. The risk of events increases with increasingly higher disease severity categories. Reprinted with permission from Min et al16

Plaque remodeling and plaque composition

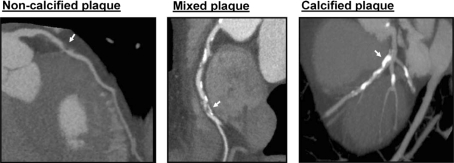

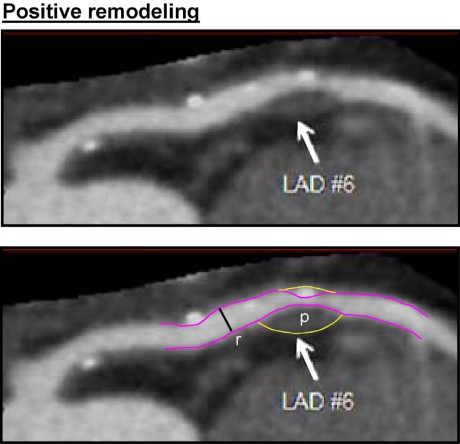

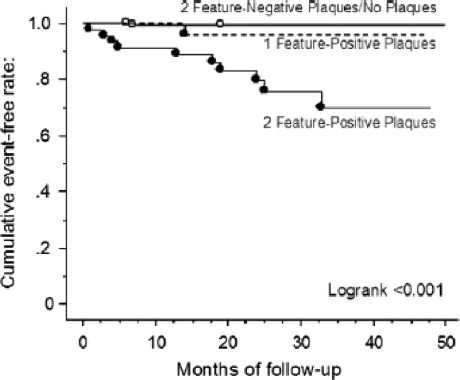

To some extent, CTA allows assessment of plaque composition. A differentiation can be made between non-calcified plaques having low attenuation, calcified plaques with high attenuation, and mixed plaques with both non-calcified and calcified elements (Figure 3).47 Furthermore, plaque remodeling, a marker of vulnerability, can also be appreciated (Figure 4). In retrospective studies comparing observations on CTA between patients presenting with stable CAD and patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome (ACS), more outward plaque remodeling, non-calcified plaque, and mixed plaque were observed in the latter.41,50,51 In subsequent prognostic investigations these characteristics have been further studied. Pundziute et al8 assessed the prognostic value of different plaque characteristics and observed that increased number of segments with mixed plaques was an independent predictor of events. Non-calcified plaque however has also been associated with an increased risk for events. Both the number of segments with mixed plaques as well as the number of segments with non-calcified plaque were independent predictors of events in a recent study by Van Werkhoven et al.20 Furthermore, the presence of substantial non-calcified plaque burden was demonstrated to provide incremental prognostic value over the presence of significant stenosis on CTA. In a recent study by Motoyama et al17 the concept of plaque morphology was investigated more extensively in 1059 patients during an average follow up of 27 months. The authors assessed the presence of two plaque characteristics, low attenuation plaque and positive remodeling, and recorded the occurrence of ACS during follow-up. In patients with a normal CTA study no events occurred. In patients with atherosclerosis but without either high-risk plaque feature (e.g., absence of both low-attenuation plaque tissue and positive remodeling) the event rate was 0.49% whereas in patients with plaques positive for 1 high-risk feature (either low attenuation or positive remodeling) the event rate increased to 3.7%. Finally, the majority of events occurred in patients with both high-risk plaque features. In these patients an event rate as high as 22.2% was observed (Figure 5). Accordingly, these findings may provide a proof of concept for the assessment of plaque composition on CTA for risk stratification.

Figure 3.

Plaque composition assessed with CTA. Curved multi-planar reconstructions showing three distinct plaque characteristics observed on CTA with non-calcified plaque (arrow, left panel), mixed plaque (arrow, mid-panel), and calcified plaque (arrow, right panel). CTA, Multi-slice computed tomography coronary angiography

Figure 4.

Example of a positively remodeled plaque. A multi-planar reconstruction of the left anterior descending coronary artery. In the proximal section of the vessel a large plaque can be observed between the lumen (purple line) and the vessel wall (yellow line). The diameter of the vessel at the plaque site is clearly larger compared to the diameter at the reference section (r), indicating positive remodeling (p). Adapted and reprinted with permission from Motoyama et al.17 LAD, Left anterior descending artery

Figure 5.

Prognostic value of low-attenuation plaque and plaque remodeling features. Survival curves illustrating the prognostic value of 2 plaque features (low-attenuation plaque and remodeling) associated with acute coronary syndrome. The event rate increased in patients with 1 feature positive plaques and was highest in patients with both high risk features. Reprinted with permission from Motoyama et al17

Integration into Clinical Practice

Relation to Existing Tools for Risk Stratification

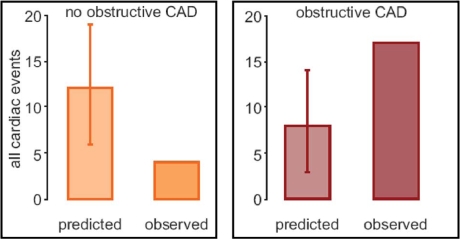

As outlined above, several investigations have demonstrated the feasibility of CTA for risk stratification. An important question however remains whether the technique provides incremental prognostic information to existing risk stratification methods. To a large extent, prognosis is determined using baseline clinical characteristics. To this end the Framingham score is widely used and provides an estimate of the risk of developing adverse coronary events.52 The disadvantage of this method is that it is a population-based screening tool, whereas CTA may provide a more patient-specific approach. In a recent investigation by Hadamitzky et al15 the value of risk stratification with CTA was compared to the Framingham risk score in a population of 1256 patients during an average follow-up of 18 months. Figure 6 illustrates the difference between the predicted risk based on the Framingham risk score and the observed risk according to findings on CTA. In patients without obstructive CAD on CTA, the observed risk was significantly lower than predicted by the Framingham risk score. In contrast significantly more events were observed in patients with obstructive CAD compared to the predicted event rate. CTA may therefore further refine risk stratification over conventional risk assessment alone.

Figure 6.

Prognostic value of CTA in addition to the Framingham risk score. In patients without obstructive CAD, the observed risk was significantly lower than predicted by the Framingham risk score. In contrast significantly more events were observed in patients with obstructive CAD compared to the predicted event rate. Reprinted with permission from Hadamitzky et al.15 CAD, Coronary artery disease

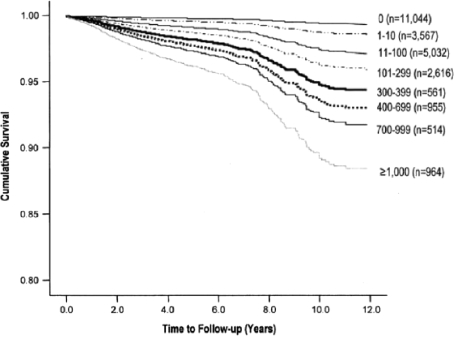

Of note, the incremental value of atherosclerosis over traditional risk assessment has been shown in the past for coronary artery calcium scoring (Figure 7).53-56 Based on numerous trials, coronary artery calcium scoring—performed either by electron beam computed tomography or CT—has been accepted as a robust tool for prognostification, especially in asymptomatic individuals.57 In addition, the technique may be used in symptomatic patients to identify the presence and the extent of atherosclerosis.58 However, the technique can only provide an estimate of total calcified plaque burden, and does not provide any information on the stenosis severity nor the presence and extent of non-calcified plaque burden. An important advantage of CTA therefore is the additional information on stenosis severity and plaque composition. In a study by Ostrom et al18 the incremental value of non-invasive coronary angiography with electron-beam-computed tomography over coronary calcium was assessed. The authors demonstrated that CTA-derived plaque burden, defined as the number of non-significantly or significantly diseased vessels, had independent and incremental value in predicting all-cause mortality independent of age, gender, conventional risk factors, and coronary artery calcium score. Similar findings were recently reported by Rubinshtein et al.19 In a more recent study the incremental prognostic value of both stenosis severity and plaque composition on CTA over the coronary artery calcium score was determined.21 In addition to stenosis severity the number of segments with non-calcified plaque as well as the number of segments with mixed plaque was shown to be independently associated with increased risk for events. Accordingly, it appears that non-invasive measures of plaque extent, severity, and composition not only provide improved diagnostic information but also incremental prognostic information over coronary artery calcium scoring.

Figure 7.

Prognostic value of coronary calcium scoring. Cumulative survival curves illustrating the event rate in increasingly higher calcium score categories. Reprinted with permission from Budoff et al54

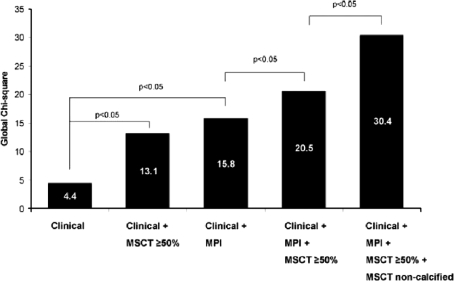

Although risk stratification using non-invasive anatomic imaging is gaining momentum, traditionally functional imaging has been used extensively for this purpose. Particularly myocardial perfusion imaging is an established and important technique for prognosis. Patients with a normal perfusion have a very low event rate compared to increased event rates in patients with abnormal perfusion59-65 Comparative studies between CTA and myocardial perfusion imaging have shown that CTA provides complementary information to myocardial perfusion imaging when regarding the diagnosis of CAD.66-69 The added value of this complementary information for risk stratification was recently determined.20 Several CTA variables were able to provide prognostic information independent of myocardial perfusion imaging. On a patient level the presence of significant CAD (≥50% stenosis) was identified as a robust independent predictor. In addition to stenosis severity, plaque composition was shown to further enhance risk stratification, as illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Incremental prognostic value of CTA over MPI. Bar graph illustrating the incremental prognostic value (depicted by Chi-square value on the y axis) of CTA. The addition of CTA provides incremental prognostic information to baseline clinical variables and MPI. Furthermore, the addition of non-calcified plaque on CTA results in further incremental prognostic information over baseline clinical variables, MPI, and significant CAD (≥50% stenosis) on CTA. Reprinted with permission from Van Werkhoven et al.20 CAD, Coronary artery disease; CTA, multi-slice computed tomography coronary angiography; MPI, myocardial perfusion imaging

Patient Populations

Symptomatic populations

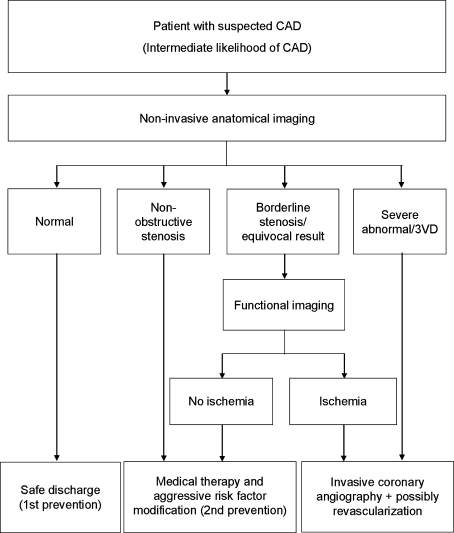

CTA has been proposed for diagnosis of significant CAD in symptomatic patients presenting with an intermediate pre-test likelihood for significant stenosis. Based on the diagnostic accuracy of CTA for the detection of significant CAD on conventional coronary angiography, the comparative studies between CTA and myocardial perfusion imaging, and the limited prognostic data at the time, an algorithm has been proposed which integrates the use of these techniques for the diagnosis and management of this patient population (Figure 9).70 The algorithm separates patients into three strategies for management: first, patients with normal coronary anatomy can be safely discharged, secondly patients with non-flow limiting atherosclerosis requiring medical treatment and aggressive risk factor modification and finally patients with a flow-limiting stenosis requiring further evaluation with conventional coronary angiography with potential revascularization. The currently available outcome data support that the discharge of patients with a normal CTA study is safe as low events rates have been confirmed in these patients.8-10,12-14,18,20,34 However in patients with atherosclerosis regardless of stenosis severity, assessment of plaque extent, composition, location, and remodeling may further improve risk stratification. As indicated by initial data, this information can be valuable both in patients with or without ischemia.20

Figure 9.

Algorithm illustrating the sequential use of CTA and functional imaging in patients with an intermediate pre-test likelihood. Reprinted with permission from Schuijf et al.70 CTA, Multi-slice computed tomography coronary angiography

CTA is currently not recommended for diagnosis in other populations than those with an intermediate pre-test likelihood for significant CAD. It is however conceivable that in the future CTA may be used in other populations with the purpose of risk stratification. In symptomatic patients with a low pre-test likelihood for significant stenosis, non-invasive imaging is generally not indicated for diagnosis. However assessment of atherosclerosis can be useful in identifying patients at increased risk of future events. As shown by Henneman et al, the prevalence of atherosclerosis in patients with a low pre-test likelihood is approximately 40% which illustrates that, although the pre-test likelihood for significant stenosis is low, atherosclerosis is nevertheless present in a large proportion of these patients. In patients with a high pre-test likelihood for significant stenosis, functional data may be more relevant than CTA to determine need for revascularization. However, CTA can potentially be used as a second line test for risk stratification as the anatomic information has been shown to provide incremental prognostic information to myocardial perfusion imaging alone.20

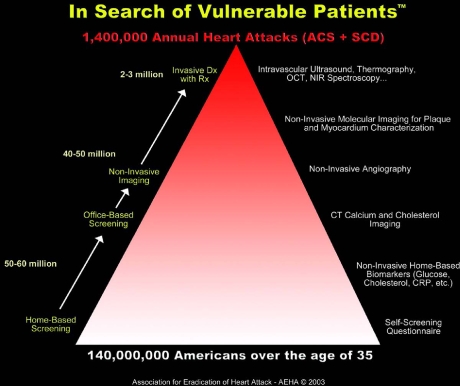

Asymptomatic populations

Although only limited data are available in asymptomatic patient populations it is possible that CTA is valuable for risk stratification in these patients. On the one hand, CTA can be used to identify patients with severe CAD, such as triple vessel disease or left main disease, and who may benefit from aggressive intervention. On the other hand, CTA can be performed to document atherosclerosis for long-term risk assessment. In a recent study in 1000 asymptomatic individuals undergoing CTA the prevalence of atherosclerosis was reported to be 22%.11 During a follow-up of 17 months, coronary events (unstable angina and revascularization) occurred in 15 (1.5%) individuals, all of which had atherosclerosis on CTA. However, the majority of events were revascularizations, triggered by the CTA results. In combination with the low overall event rate, these observations indicate the limited value of screening for atherosclerosis with CTA in this population. Accordingly, CTA is currently not acceptable as a general screening tool and CS testing or truly non-invasive approaches may be preferable. However, as proposed by Naghavi et al36 non-invasive coronary angiography may potentially be used as a downstream test in the workup of asymptomatic individuals with high-risk characteristics, following home- or office-based screening (Figure 10). Through selection of high-risk patients with truly non-invasive techniques only a small subgroup of high-risk patients remains in which further non-invasive and subsequent invasive imaging may be beneficial. Future studies will need to determine the value and feasibility of such a screening strategy.

Figure 10.

Potential screening algorithm for the identification of vulnerable plaque in asymptomatic individuals. An example of an algorithm with potential usefulness in the workup of high-risk patients, to identify the presence of plaques with vulnerable characteristics. At the bottom of the pyramid, individuals are selected for further non-invasive evaluation with CS testing and CTA based on home-based screening questionnaires and biomarker assessment. At the top of the pyramid a small subgroup remains warranting further invasive assessment. Ideally such an algorithm can be used to identify a subgroup of the general asymptomatic populations in need of aggressive primary prevention strategies. Reprinted with permission from Naghavi et al.36 CS, Calcium score; CTA, multi-slice computed tomography coronary angiography

Limitations

Although the available data support the potential clinical relevance of assessment of plaque characteristics on CTA, accurate quantification of plaque remains challenging, while requiring optimal image quality. Leber et al44 have reported on the accuracy of 64-slice CTA to classify and quantify plaque volumes in the proximal coronary arteries as compared to intravascular ultrasound. CTA, detected calcified and mixed plaque with high accuracy (95 and 94%, respectively) but accuracy was lower for non-calcified lesions (83%). When regarding plaque volume, non-calcified plaque and mixed plaque volumes were systematically underestimated whereas calcified plaque volume was overestimated by CTA. Novel software packages aimed at assessing plaque volume and plaque composition are currently being developed and may improve not only accuracy but also reproducibility of measurements.

In addition, the radiation dose remains a cause of concern for CTA. Currently traditional 64-slice CTA protocols are still associated with high radiation exposure, although the radiation dose of CTA has recently decreased substantially.71-74 Importantly, low-dose CTA with prospective ECG triggering has recently been shown to reduce radiation burden while maintaining image quality and a high diagnostic accuracy.75,76 Currently, the radiation burden with these novel acquisition techniques is approaching the level of diagnostic catheterization or even lower.77

Conclusion

Non-invasive anatomic assessment of plaque burden, location, composition, and remodeling using CTA may provide prognostically relevant information, incremental to not only the Framingham risk score, but also to other imaging approaches as coronary artery calcium scoring and myocardial perfusion imaging. Thus, non-invasive characterization of atherosclerosis has the potential to provide a more patient-tailored approach to disease management. Future studies assessing outcome after CTA-based risk adjustments are needed to further understand the value of detailed non-invasive anatomic imaging.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Footnotes

Jacob van Werkhoven is financially supported by a research grant from the Netherlands Society of Cardiology (Utrecht, The Netherlands). Jeroen J. Bax has research grants from Medtronic (Tolochenaz, Switzerland), Boston Scientific (Maastricht, The Netherlands), BMS medical imaging (N. Billerica, MA, USA), St. Jude Medical (Veenendaal, The Netherlands), Biotronik (Berlin, Germany), GE Healthcare (St. Giles, United Kingdom), and Edwards Lifesciences (Saint-Prex, Switzerland).

Contributor Information

Jacob M. van Werkhoven, Email: j.m.van_werkhoven@lumc.nl.

Joanne D. Schuijf, Phone: +31-71-5262020, FAX: +31-71-5266809, Email: j.d.schuijf@lumc.nl.

References

- 1.van Werkhoven JM, Schuijf JD, Jukema JW, Kroft LJ, Stokkel MP, bbets-Schneider P, et al. Anatomic correlates of a normal perfusion scan using 64-slice computed tomographic coronary angiography. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller JM, Rochitte CE, Dewey M, Arbab-Zadeh A, Niinuma H, Gottlieb I, et al. Diagnostic performance of coronary angiography by 64-row CT. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2324–2336. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schuijf JD, Pundziute G, Jukema JW, Lamb HJ, van der Hoeven BL, de RA, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of 64-slice multislice computed tomography in the noninvasive evaluation of significant coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:145–148. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.01.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Budoff MJ, Dowe D, Jollis JG, Gitter M, Sutherland J, Halamert E, et al. Diagnostic performance of 64-multidetector row coronary computed tomographic angiography for evaluation of coronary artery stenosis in individuals without known coronary artery disease: Results from the prospective multicenter ACCURACY (Assessment by Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography of Individuals Undergoing Invasive Coronary Angiography) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1724–1732. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meijboom WB, Meijs MFL, Schuijf JD, Cramer MJ, Mollet NR, Van Mieghem CA, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of 64-slice computed tomography coronary angiography: A prospective multicenter, multivendor study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:2135–2144. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdulla J, Abildstrom SZ, Gotzsche O, Christensen E, Kober L, Torp-Pedersen C. 64-multislice detector computed tomography coronary angiography as potential alternative to conventional coronary angiography: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:3042–3050. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mowatt G, Cook JA, Hillis GS, Walker S, Fraser C, Jia X, et al. 64-slice computed tomography angiography in the diagnosis and assessment of coronary artery disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2008;94:1386–1393. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2008.145292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pundziute G, Schuijf JD, Jukema JW, Boersma E, de Roos A, van der Wall EE, et al. Prognostic value of multislice computed tomography coronary angiography in patients with known or suspected coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aldrovandi A, Maffei E, Palumbo A, Seitun S, Martini C, Brambilla V, et al. Prognostic value of computed tomography coronary angiography in patients with suspected coronary artery disease: A 24-month follow-up study. Eur Radiol 2009;19:1653-60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Carrigan TP, Nair D, Schoenhagen P, Curtin RJ, Popovic ZB, Halliburton S, et al. Prognostic utility of 64-slice computed tomography in patients with suspected but no documented coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:362–371. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi EK, Choi SI, Rivera JJ, Nasir K, Chang SA, Chun EJ, et al. Coronary computed tomography angiography as a screening tool for the detection of occult coronary artery disease in asymptomatic individuals. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:357–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.02.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaemperli O, Valenta I, Schepis T, Husmann L, Scheffel H, Desbiolles L, et al. Coronary 64-slice CT angiography predicts outcome in patients with known or suspected coronary artery disease. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:1162–1173. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-0871-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilard M, Le Gal G, Cornily J, Vinsonneau U, Joret C, Pennec P, et al. Midterm prognosis of patients with suspected coronary artery disease and normal multislice computed tomographic findings. Arch Intern Med. 2007;165:1686–1689. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.15.1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gopal A, Nasir K, Ahmadi N, Gul K, Tiano J, Flores M, et al. Cardiac computed tomographic angiography in an outpatient setting: An analysis of clinical outcomes over a 40-month period. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2009;3:90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hadamitzky M, Freissmuth B, Meyer T, Hein F, Kastrati A, Martinoff S, et al. Prognostic value of coronary computed tomographic angiography for prediction of cardiac events in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol Imaging. 2009;2:404–411. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Min JK, Shaw LJ, Devereux RB, Okin PM, Weinsaft JW, Russo DJ, et al. Prognostic value of multidetector coronary computed tomographic angiography for prediction of all-cause mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1161–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Motoyama S, Sarai M, Harigaya H, Anno H, Inoue K, Hara T, et al. Computed tomographic angiography characteristics of atherosclerotic plaques subsequently resulting in acute coronary syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ostrom MP, Gopal A, Ahmadi N, Nasir K, Yang E, Kakadiaris I, et al. Mortality incidence and the severity of coronary atherosclerosis assessed by computed tomography angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1335–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubinshtein R, Halon DA, Gaspar T, Peled N, Lewis BS. Cardiac computed tomographic angiography for risk stratification and prediction of late cardiovascular outcome events in patients with a chest pain syndrome. Int J Cardiol 2008, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.van Werkhoven JM, Schuijf JD, Gaemperli O, Jukema JW, Boersma E, Wijns W, et al. Prognostic value of multislice computed tomography and gated single-photon emission computed tomography in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:623–632. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Werkhoven JM, Schuijf JD, Gaemperli O, Jukema JW, Kroft LJ, Boersma E, et al. Incremental prognostic value of multi-slice computed tomography coronary angiography over coronary artery calcium scoring in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J 2009, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Hamon M, Biondi-Zoccai GG, Malagutti P, Agostoni P, Morello R, Valgimigli M, et al. Diagnostic performance of multislice spiral computed tomography of coronary arteries as compared with conventional invasive coronary angiography: A meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1896–1910. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hausleiter J, Meyer T, Hadamitzky M, Zankl M, Gerein P, Dorrler K, et al. Non-invasive coronary computed tomographic angiography for patients with suspected coronary artery disease: The Coronary Angiography by Computed Tomography with the Use of a Submillimeter resolution (CACTUS) trial. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:3034–3041. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leber AW, Knez A, von Ziegler F, Becker A, Nikolaou K, Paul S, et al. Quantification of obstructive and nonobstructive coronary lesions by 64-slice computed tomography: A comparative study with quantitative coronary angiography and intravascular ultrasound. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mollet NR, Cademartiri F, Van Mieghem CAG, Runza G, McFadden EP, Baks T, et al. High-resolution spiral computed tomography coronary angiography in patients referred for diagnostic conventional coronary angiography. Circulation. 2005;112:2318–2323. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.533471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raff GL, Gallagher MJ, O’Neill WW, Goldstein JA. Diagnostic accuracy of noninvasive coronary angiography using 64-slice spiral computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:552–557. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DeWood MA, Spores J, Notske R, Mouser LT, Burroughs R, Golden MS, et al. Prevalence of total coronary occlusion during the early hours of transmural myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:897–902. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198010163031601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Solomon HA, Edwards AL, Killip T. Prodromatan acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1969;40:463–471. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.40.4.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stowers M, Short D. Warning symptoms before major myocardial infarction. Br Heart J. 1970;32:833–838. doi: 10.1136/hrt.32.6.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ambrose JA, Tannenbaum MA, Alexopoulos D, Hjemdahl-Monsen CE, Leavy J, Weiss M, et al. Angiographic progression of coronary artery disease and the development of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988;12:56–62. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(88)90356-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Little WC, Constantinescu M, Applegate RJ, Kutcher MA, Burrows MT, Kahl FR, et al. Can coronary angiography predict the site of a subsequent myocardial infarction in patients with mild-to-moderate coronary artery disease? Circulation. 1988;78:1157–1166. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.78.5.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nobuyoshi M, Tanaka M, Nosaka H, Kimura T, Yokoi H, Hamasaki N, et al. Progression of coronary atherosclerosis: Is coronary spasm related to progression? J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;18:904–910. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(91)90745-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giroud D, Li JM, Urban P, Meier B, Rutishauer W. Relation of the site of acute myocardial infarction to the most severe coronary arterial stenosis at prior angiography. Am J Cardiol. 1992;69:729–732. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(92)90495-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van LR, Kakani N, Veitch A, Manghat NE, Roobottom CA, Morgan-Hughes GJ. Prognostic and accuracy data of multidetector CT coronary angiography in an established clinical service. Clin Radiol. 2009;64:601–607. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Virmani R, Burke AP, Farb A, Kolodgie FD. Pathology of the vulnerable plaque. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:C13–C18. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naghavi M, Libby P, Falk E, Casscells SW, Litovsky S, Rumberger J, et al. From vulnerable plaque to vulnerable patient: A call for new definitions and risk assessment strategies: Part II. Circulation. 2003;108:1772–1778. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000087481.55887.C9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Achenbach S, Ropers D, Hoffmann U, MacNeill B, Baum U, Pohle K, et al. Assessment of coronary remodeling in stenotic and nonstenotic coronary atherosclerotic lesions by multidetector spiral computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:842–847. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Achenbach S, Moselewski F, Ropers D, Ferencik M, Hoffmann U, MacNeill B, et al. Detection of calcified and noncalcified coronary atherosclerotic plaque by contrast-enhanced, submillimeter multidetector spiral computed tomography: A segment-based comparison with intravascular ultrasound. Circulation. 2004;109:14–17. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000111517.69230.0F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Becker CR, Nikolaou K, Muders M, Babaryka G, Crispin A, Schoepf UJ, et al. Ex vivo coronary atherosclerotic plaque characterization with multi-detector-row CT. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:2094–2098. doi: 10.1007/s00330-003-1889-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cordeiro MA, Lima JA. Atherosclerotic plaque characterization by multidetector row computed tomography angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:C40–C47. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoffmann U, Moselewski F, Nieman K, Jang IK, Ferencik M, Rahman AM, et al. Noninvasive assessment of plaque morphology and composition in culprit and stable lesions in acute coronary syndrome and stable lesions in stable angina by multidetector computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1655–1662. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Komatsu S, Hirayama A, Omori Y, Ueda Y, Mizote I, Fujisawa Y, et al. Detection of coronary plaque by computed tomography with a novel plaque analysis system, ‘Plaque Map’, and comparison with intravascular ultrasound and angioscopy. Circ J. 2005;69:72–77. doi: 10.1253/circj.69.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leber AW, Knez A, Becker A, Becker C, von Ziegler F, Nikolaou K, et al. Accuracy of multidetector spiral computed tomography in identifying and differentiating the composition of coronary atherosclerotic plaques: A comparative study with intracoronary ultrasound. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1241–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.10.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leber AW, Becker A, Knez A, von Ziegler F, Sirol M, Nikolaou K, et al. Accuracy of 64-slice computed tomography to classify and quantify plaque volumes in the proximal coronary system: A comparative study using intravascular ultrasound. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:672–677. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Motoyama S, Kondo T, Anno H, Sugiura A, Ito Y, Mori K, et al. Atherosclerotic plaque characterization by 0.5-mm-slice multislice computed tomographic imaging. Circ J. 2007;71:363–366. doi: 10.1253/circj.71.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pohle K, Achenbach S, MacNeill B, Ropers D, Ferencik M, Moselewski F, et al. Characterization of non-calcified coronary atherosclerotic plaque by multi-detector row CT: Comparison to IVUS. Atherosclerosis. 2007;190:174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schroeder S, Kopp AF, Baumbach A, Meisner C, Kuettner A, Georg C, et al. Noninvasive detection and evaluation of atherosclerotic coronary plaques with multislice computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:1430–1435. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01115-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schroeder S, Kuettner A, Leitritz M, Janzen J, Kopp AF, Herdeg C, et al. Reliability of differentiating human coronary plaque morphology using contrast-enhanced multislice spiral computed tomography: A comparison with histology. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2004;28:449–454. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200407000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kolodgie FD, Burke AP, Farb A, Gold HK, Yuan J, Narula J, et al. The thin-cap fibroatheroma: A type of vulnerable plaque: The major precursor lesion to acute coronary syndromes. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2001;16:285–292. doi: 10.1097/00001573-200109000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schuijf JD, Beck T, Burgstahler C, Jukema JW, Dirksen MS, de Roos A, et al. Differences in plaque composition and distribution in stable coronary artery disease versus acute coronary syndromes; non-invasive evaluation with multi-slice computed tomography. Acute Card Care. 2007;9:48–53. doi: 10.1080/17482940601052648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Motoyama S, Kondo T, Sarai M, Sugiura A, Harigaya H, Sato T, et al. Multislice computed tomographic characteristics of coronary lesions in acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:319–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB, Levy D, Belanger AM, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998;97:1837–1847. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.18.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arad Y, Goodman KJ, Roth M, Newstein D, Guerci AD. Coronary calcification, coronary disease risk factors, C-reactive protein, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events: The St Francis Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Budoff MJ, Shaw LJ, Liu ST, Weinstein SR, Mosler TP, Tseng PH, et al. Long-term prognosis associated with coronary calcification: Observations from a registry of 25, 253 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1860–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Detrano R, Guerci AD, Carr JJ, Bild DE, Burke G, Folsom AR, et al. Coronary calcium as a predictor of coronary events in four racial or ethnic groups. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1336–1345. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Greenland P, LaBree L, Azen SP, Doherty TM, Detrano RC. Coronary artery calcium score combined with Framingham score for risk prediction in asymptomatic individuals. JAMA. 2004;291:210–215. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Greenland P, Bonow RO, Brundage BH, Budoff MJ, Eisenberg MJ, Grundy SM, et al. ACCF/AHA 2007 clinical expert consensus document on coronary artery calcium scoring by computed tomography in global cardiovascular risk assessment and in evaluation of patients with chest pain: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Clinical Expert Consensus Task Force (ACCF/AHA Writing Committee to Update the 2000 Expert Consensus Document on Electron Beam Computed Tomography) developed in collaboration with the Society of Atherosclerosis Imaging and Prevention and the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:378–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sarwar A, Shaw LJ, Shapiro MD, Blankstein R, Hoffman U, Cury RC, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic value of absence of coronary artery calcification. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:675–688. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Elhendy A, Schinkel A, Bax JJ, van Domburg RT, Poldermans D. Long-term prognosis after a normal exercise stress Tc-99m sestamibi SPECT study. J Nucl Cardiol. 2003;10:261–266. doi: 10.1016/S1071-3581(02)43219-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Elhendy A, Schinkel AFL, van Domburg RT, Bax JJ, Valkema R, Biagini E, et al. Prognostic value of stress Tc-99m-tetrofosmin myocardial perfusion imaging in predicting all-cause mortality: A 6-year follow-up study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2006;33:1157–1161. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0140-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hachamovitch R, Berman DS, Kiat H, Cohen I, Cabico JA, Friedman J, et al. Exercise myocardial perfusion SPECT in patients without known coronary artery disease: Incremental prognostic value and use in risk stratification. Circulation. 1996;93:905–914. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.5.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stratmann HG, Williams GA, Wittry MD, Chaitman BR, Miller DD. Exercise technetium-99m sestamibi tomography for cardiac risk stratification of patients with stable chest pain. Circulation. 1994;89:615–622. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.2.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thomas GS, Miyamoto MI, Morello AP, III, Majmundar H, Thomas JJ, Sampson CH, et al. Technetium 99m sestamibi myocardial perfusion imaging predicts clinical outcome in the community outpatient setting. The Nuclear Utility in the Community (NUC) Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Underwood SR, Anagnostopoulos C, Cerqueira M, Ell PJ, Flint EJ, Harbinson M, et al. Myocardial perfusion scintigraphy: The evidence—a consensus conference organised by the British Cardiac Society, the British Nuclear Cardiology Society and the British Nuclear Medicine Society, endorsed by the Royal College of Physicians of London and the Royal College of Radiologists. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;31:261–291. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1344-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shaw LJ, Iskandrian AE. Prognostic value of gated myocardial perfusion SPECT. J Nucl Cardiol. 2004;11:171–185. doi: 10.1016/j.nuclcard.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gaemperli O, Schepis T, Koepfli P, Valenta I, Soyka J, Leschka S, et al. Accuracy of 64-slice CT angiography for the detection of functionally relevant coronary stenoses as assessed with myocardial perfusion SPECT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:1162–1171. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0307-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hacker M, Jakobs T, Hack N, Nikolaou K, Becker C, von Ziegler F, et al. Sixty-four slice spiral CT angiography does not predict the functional relevance of coronary artery stenoses in patients with stable angina. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:4–10. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0207-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rispler S, Keidar Z, Ghersin E, Roguin A, Soil A, Dragu R, et al. Integrated single-photon emission computed tomography and computed tomography coronary angiography for the assessment of hemodynamically significant coronary artery lesions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1059–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schuijf JD, Wijns W, Jukema JW, Atsma DE, de Roos A, Lamb HJ, et al. The relationship between non-invasive coronary angiography with multi-slice computed tomography and myocardial perfusion imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:2508–2514. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.05.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schuijf JD, Jukema JW, van der Wall EE, Bax JJ. The current status of multislice computed tomography in the diagnosis and prognosis of coronary artery disease. J Nucl Cardiol. 2007;14:604–612. doi: 10.1016/j.nuclcard.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hausleiter J, Meyer T, Hadamitzky M, Huber E, Zankl M, Martinoff S, et al. Radiation dose estimates from cardiac multislice computed tomography in daily practice: Impact of different scanning protocols on effective dose estimates. Circulation. 2006;113:1305–1310. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.602490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hsieh J, Londt J, Vass M, Li J, Tang X, Okerlund D. Step-and-shoot data acquisition and reconstruction for cardiac x-ray computed tomography. Med Phys. 2006;33:4236–4248. doi: 10.1118/1.2361078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Husmann L, Valenta I, Gaemperli O, Adda O, Treyer V, Wyss CA, et al. Feasibility of low-dose coronary CT angiography: First experience with prospective ECG-gating. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:191–197. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rybicki FJ, Otero HJ, Steigner ML, Vorobiof G, Nallamshetty L, Mitsouras D, et al. Initial evaluation of coronary images from 320-detector row computed tomography. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008;24:535–546. doi: 10.1007/s10554-008-9308-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Herzog BA, Husmann L, Burkhard N, Gaemperli O, Valenta I, Tatsugami F, et al. Accuracy of low-dose computed tomography coronary angiography using prospective electrocardiogram-triggering: First clinical experience. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:3037–3042. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Scheffel H, Alkadhi H, Leschka S, Plass A, Desbiolles L, Guber I, et al. Low-dose CT coronary angiography in the step-and-shoot mode: Diagnostic performance. Heart. 2008;94:1132–1137. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2008.149971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Herzog BA, Wyss CA, Husmann L, Gaemperli O, Valenta I, Treyer V, et al. First head-to-head comparison of effective radiation dose from low-dose CT with prospective ECG-triggering versus invasive coronary angiography. Heart 2009, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 78.Jain RK, Finn AV, Kolodgie FD, Gold HK, Virmani R. Antiangiogenic therapy for normalization of atherosclerotic plaque vasculature: A potential strategy for plaque stabilization. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2007;4:491–502. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]