Abstract

Confocal and total internal reflection fluorescence imaging was used to examine the distribution of caveolin-3, sodium-calcium exchange (NCX) and ryanodine receptors (RyRs) in rat ventricular myocytes. Transverse and longitudinal optical sectioning shows that NCX is distributed widely along the transverse and longitudinal tubular system (t-system). The NCX labeling consisted of both punctate and distributed components, which partially colocalize with RyRs (27%). Surface membrane labeling showed a similar pattern but the fraction of RyR clusters containing NCX label was decreased and no nonpunctate labeling was observed. Sixteen percent of RyRs were not colocalized with the t-system and 1.6% of RyRs were found on longitudinal elements of the t-system. The surface distribution of RyR labeling was not generally consistent with circular patches of RyRs. This suggests that previous estimates for the number of RyRs in a junction (based on circular close-packed arrays) need to be revised. The observed distribution of caveolin-3 labeling was consistent with its exclusion from RyR clusters. Distance maps for all colocalization pairs were calculated to give the distance between centroids of punctate labeling and edges for distributed components. The possible roles for punctate NCX labeling are discussed.

Introduction

Contraction of cardiac muscle is activated by a rapid, cell-wide increase in cytosolic Ca2+ caused by the summation of elementary Ca2+ release events (1). In rat ventricular myocytes, the majority of the Ca2+ contributing to the increase in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) is released from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) via clusters of ryanodine receptors (RyR) located in narrow dyadic junctions between the sarcolemma and flattened cisterns of terminal SR (2). The majority of these junctions occur on the transverse tubular system (t-system), which is an extension of the outer sarcolemma that spans the interior of the cell (3, 4, 5). Rapid spread of electrical activation during an action potential ensures near-simultaneous Ca2+ release throughout the cell by rapidly activating Ca2+ influx through voltage sensitive Ca2+ channels (DHPRs). The DHPRs in the t-system and on the outer sarcolemma provide the primary trigger for RyR opening (via calcium-induced calcium release (CICR) (6)). The location of DHPRs in the narrow dyadic cleft (∼15 nm wide) is thought to ensure the rapid and spatially restricted activation of adjacent RyRs because (due to the spatial confinement) the local [Ca2+] will rise within a fraction of a millisecond to several micromolar and may then exceed 100 μM once RyRs open (7, 8).

These ideas form the basis of the “local control” theory of excitation-contraction (E-C) coupling (9, 10, 11) and in support of this theory, immunolabeling studies suggest that DHPRs are highly colocalized with RyRs (12, 13, 14) forming “couplons”. Although the role of DHPRs and RyRs is relatively well established, the role of the cardiac sodium calcium exchanger (NCX) has been more controversial. NCX is the principal Ca2+ extrusion mechanism (15) that removes Ca2+ that entered the myocyte from the extracellular space via DHPRs (16). However, reversal of the exchange at positive membrane potentials and/or elevated [Na+]i could contribute to Ca2+ entry during the early phase of the action potential and augment the primary trigger Ca2+ supplied by DHPRs (17, 18, 19). This possibility is critically dependent on the position of NCX relative to the junction.

Colocalization studies by Scriven et al. (12) suggest that there is very little colocalization between NCX and RyR in rat myocytes and they concluded that NCX is not present in (or close to) junctions. In contrast, work by Thomas et al. (20) showed that the distribution of NCX and RyRs were similar and immunogold labeling suggested NCX within junctions. Some of the differences between these studies could reflect different antibody properties and it is notable that Thomas et al. (20), although not providing quantitative analyses of colocalization, characterized their antibody specificity in detail. In agreement with observation of Thomas et al. (20), Trafford et al. (21) showed that INa/Ca was consistent with the location of NCX in a compartment with increased [Ca2+]i that may correspond to the dyadic space. A number of additional experimental studies support the ability of NCX to synergistically enhance the DHPR trigger during E-C coupling (22, 23, 24). The ability of theoretical models to explain these findings strongly depends on assumptions about the (controversial) distribution of NCX (23, 25). Depending on its location, NCX could also play an important role in regulation of the Ca2+ transient (26) by affecting SR load. Clearly, a firm mathematical basis for Ca2+ handling in cardiac myocytes requires quantitative knowledge of the distribution of NCX relative to the architecture of the t-system and dyadic junctions.

The measurement and interpretation of confocal immunofluorescence data in ventricular myocytes has often been complicated by the interaction of the asymmetric point spread function (PSF) with the complex geometry of the t-system (12, 20, 27, 28). We investigate the structure of the t-system and its spatial relationship to the distribution of RyRs and NCX in isolated rat ventricular myocytes using a cell orientation that greatly reduces the influence of geometrical factors on the obtained data (29, 30). We identify a subpopulation of apparently nonjunctional RyRs and clarify the location of NCX, which we show to be heterogeneously distributed within the t-system and on the surface membrane.

Materials and Methods

Immunocytochemistry and imaging preparation

A suspension of fixed myocytes (see the Supporting Material) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was mixed with agarose (Cambrex, Rockland, ME) in PBS solution at 37°C to a final concentration of 3% (w/v) and cooled to room temperature. Cells embedded in agarose blocks were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X100 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in PBS for 10 min, blocked in PBS containing 10% normal goat serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and incubated with the primary antibodies (Abs) overnight at 4°C. The cells were washed three times in PBS for 2 h and the secondary Ab was applied overnight at 4°C. After three further washes, 1-mm slices were cut from the agar blocks and mounted on a No. 1.5 glass coverslip, embedding the slice in ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Molecular Probes/Invitrogen, Auckland, NZ). The specimen was allowed to cure for ∼48 h and sealed within a chamber that could be mounted in the translation stage of the microscope. Cells were labeled with Abs against RyR2, NCX1, and caveolin-3 (CAV3) as well as secondary Abs conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 and 594. See the Supporting Material for details.

Imaging and image processing

Fluorescent images were recorded with either a FV1000 laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) using an Olympus 60× 1.35 NA oil-immersion objective or an Axiovert LSM410 laser scanning microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) and a Zeiss 63× 1.25 NA oil-immersion objective. Alexa 488 and Alexa 594 fluorochromes were excited with an Ar+ 488 laser and a HeNe 543 nm laser respectively. The method of Chen-Izu et al. (29) was used to obtain high-resolution transverse optical sections of embedded myocytes. Transverse confocal sections of the cells were acquired with Z-spacings of 0.2–0.25 μm and stored in 8-bit or 12-bit format for offline processing. The three-dimensional (3D) PSF for deconvolution was measured by imaging 100 nm Fluospheres mounted in ProLong Gold (Molecular Probes/Invitrogen) or saturated sucrose solution. Before quantitative analysis, the data were processed with constrained iterative maximal-likelihood deconvolution using a Richardson-Lucy algorithm as described (3) to improve the signal/noise ratio.

Fluorescence imaging of myocyte surface labeling

Blocks of agar in PBS were mounted on a No. 1.5 coverslip and pressed down gently by a second coverslip. The sample was imaged in total internal reflectance fluorescence (TIRF) on a Nikon TE2000 inverted microscope with a Nikon 60x 1.49NA objective and an Andor IXon DV887DCS-BV electron multiplying charge-coupled device camera (Andor Technology, Belfast, Northern Ireland). Alexa 488 (RyR) and Alexa 594 (NCX) were imaged sequentially with 488 nm and 532 nm laser lines and emission collected between 500 and 550 nm and 590 and 650, nm, respectively.

Spatial analysis of protein distribution

All quantitative analyses were carried out using custom routines written in IDL (ITT, Boulder, CO). Confocal data were analyzed in 3D whereas TIRF images were analyzed as 2D images. Centroids of punctate labeling were determined using a cluster detection algorithm, as described in Soeller et al. (30) (see the Supporting Material). For dual wavelength data, the Euclidian distance between centroids in each channel were calculated and for convenience (and to make the data easily relatable to other wide field data) we define nearest-neighbor centroids <150 nm apart in X-Y and <300 nm apart in Z to be colocalized.

To characterize data that was extended (i.e., not punctate) we calculated the Euclidian distances between labeled regions. To calculate the distance to the labeled region, a nonlinear threshold algorithm (Supporting Material) was used to measure the percentage of labeling in one channel (label A) as a function of the distance to the identified staining mask in the other channel (label B). The colocalized fraction of label B was calculated as the (intensity weighted) fraction of label B found within the binary mask of label A.

These colocalization measures were evaluated with two test samples (see the Supporting Material). The determination of t-tubular connectivity is described in the Supporting Material.

Results

Visualization of the t-system architecture

In longitudinal confocal sections, immunolabeling of the membrane protein CAV3 produced clear labeling that extended transversely across the width of the cell as described by others (27, 31) (Fig. 1A). Closer inspection of these data showed fine elements of CAV3 labeling resembling longitudinal t-tubules seen in intact cells (3). The longitudinal elements often bridged 4–5 consecutive Z-lines (Fig. 1A). In transverse confocal sections, (produced by imaging cells oriented parallel to the optical axis) the staining pattern of CAV3 formed a thin network that spanned the cell cross-section (Fig. 1B). In addition, there was a ring of bright labeling around the cell periphery that reflects sarcolemmal CAV3 expression. The improved resolution afforded by these transverse confocal sections becomes clear by comparing a resectioned y-z slice from a cell imaged in the longitudinal orientation (as seen in Fig. 1A). In this orientation, the elongated point-spread-function along the optical axis leads to an effective loss of resolution within the Z-disk plane and emphasizes t-tubule segments that run in the Z-direction as shown in Fig. 1C. Due to these imaging artifacts, the looped structure of the t-system could not be reliably observed in resectioned longitudinal data sets. The distance between Z-disks (∼1.8 μm) was large enough to prevent blurring along the axis of vertically oriented myocytes, as shown in Fig. 1D that shows a 3D rendering of two adjacent Z-disks (and shows the similarity in t-system structure at adjacent Z-lines). It was also possible to identify longitudinal elements of the t-system that extended between Z-lines as shown in Fig. 1E. These data demonstrate that CAV3 staining in transverse confocal sections outlines the t-system at high resolution.

Figure 1.

T-tubular architecture in fixed myocytes. (A) Longitudinal confocal sectioning through a CAV3-labeled myocyte shows transverse rows of Z-line-associated t-tubules throughout the interior of the cell. Longitudinal tubules were frequently observed (arrows) and often are aligned along 3–4 sarcomeres. (B) Shallow maximum intensity projection in a cell orientated vertically and imaged in transverse confocal sections (x-y plane) illustrates the complex network of t-tubules near a single Z-disk. Note the improvement in the Z-disk resolution compared to C that shows a y-z view of the t-tubules near a Z-disk in a cell imaged in longitudinal confocal sections. The blurring resulting from the asymmetric confocal PSF tends to enhance the apparent intensity of structures parallel to the Z-axis (white arrowheads). (D) A surface rendered region of the cell in B shown in x-y transverse view detailing the similarity in t-tubular connectivity at two neighboring Z-disks. (E) Examination of this volume in the y-z longitudinal orientation allows identification of longitudinal tubules (red arrowheads). Scale bars = 5 μm.

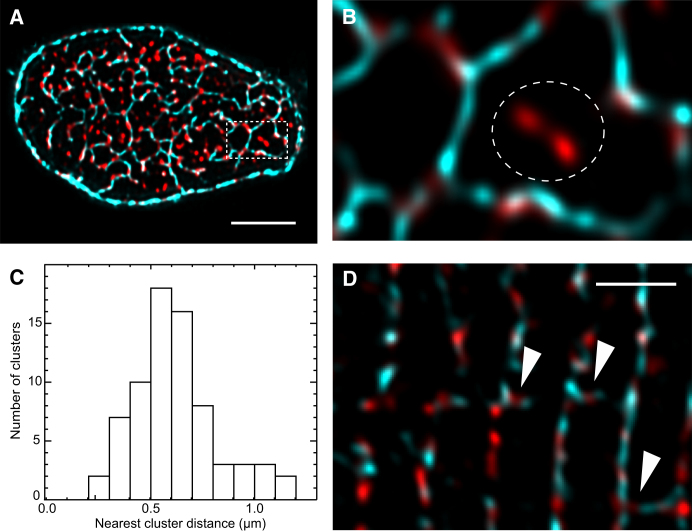

T-system architecture and relationship to RyR cluster distribution

Fig. 2A shows a projection across a single Z-disk of a cell dual-labeled for CAV3 and RyRs. Consistent with previous studies (29, 30), RyR labeling appeared punctate with a typical FWHM of ∼250–300 nm. Comparison with electron micrographs suggest that these puncta should correspond to RyR clusters (30). As expected, most RyR clusters were located on (or close to) t-tubules suggesting that they are within dyadic junctions. However, some RyR clusters were found far from t-tubules as shown in Fig. 2B. To quantify this fraction we constructed a skeleton of the t-system (see Materials and Methods) and 15.9 ± 1.1% (mean ± SD, n = 5 cells) of the RyR cluster centroids were found >250 nm from the t-tubule skeleton. Further examination of this subpopulation of RyR clusters in 3D confirmed that these clusters were also located near Z-lines. The large distance to the t-system (and sarcolemmal) staining suggests that these RyR clusters are nonjunctional. A histogram of the 3D distances between nonjunctional clusters and their nearest cluster on the t-system (Fig. 2C) had an approximately Gaussian distribution with a mean distance of 0.62 ± 0.03 μm (n = 5 cells).

Figure 2.

Spatial relationship between transverse tubules and RyR clusters. (A) A maximum intensity projection (1.25 μm) of dual-labeled transverse confocal sections illustrates CAV3 (cyan) and RyR (red) labeling near a single Z-disk. (B) An enlarged region (dashed box in A) shows that discrete RyR clusters align closely with the fine elements of the t-tubular network traced by CAV3. A small subset of RyR clusters (dashed circle) were further than 250 nm from the nearest detectable t-tubule. (C) The histogram of distances between nonjunctional RyR clusters and the nearest t-system associated cluster had a mean of 0.62 ± 0.03 μm (mean ± SD, n = 5). (D) RyR clusters found between Z-lines (arrowheads) in longitudinal confocal scans regularly coincided with elements of caveolin labeling indicating nearby longitudinal tubules. Scale bars =A, 5 μm; D, 3 μm.

The observation of longitudinal t-system connections raised the possibility of RyR clusters forming junctions with longitudinal tubules. Examination of areas where RyR clusters occurred between Z-lines showed that the vast majority coincided with a longitudinal tubule (96.5 ± 3.2% (n = 8 cells)). Additionally, some RyR clusters were elongated along the tubule (Fig. 3D) with lengths up to 1.40 μm. 62 ± 4% (n = 5 cells) of longitudinal t-tubules contained at least one patch of RyR labeling. RyR clusters at longitudinal tubules were present at a density of 15.8 ± 2.6 clusters/pL (n = 5 cells) that is ∼1.6% of the total interior couplon density of the myocyte (30).

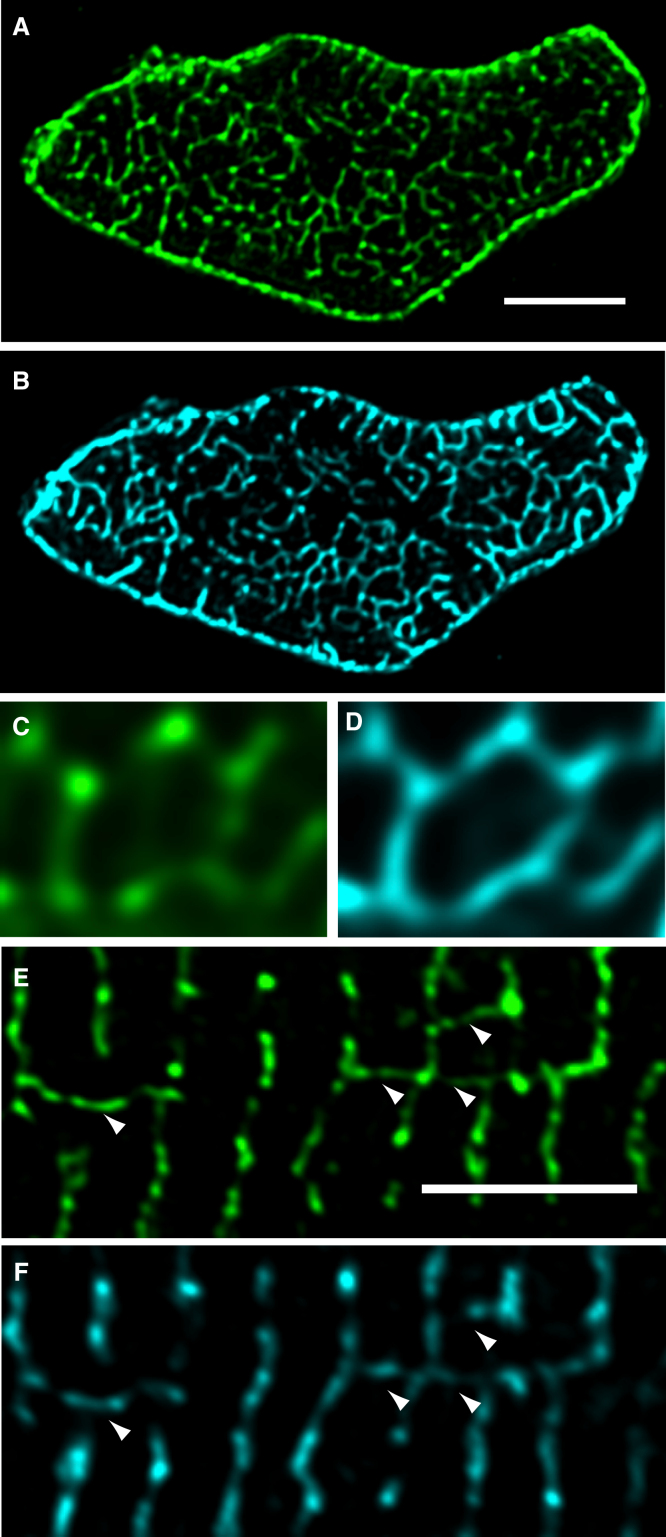

Figure 3.

T-tubular distribution of NCX. (A) A maximum intensity projection (1.25 μm) of NCX labeling near a single Z-line in transverse section shows the distribution of NCX within the t-system. (B) A projection of CAV3 labeling in the same region suggests that the network of NCX labeling is aligned with the architecture of the t-system. (C) A magnified view of NCX labeling (green), which is similar but not identical to the labeling pattern shown by CAV3 in D. (E) NCX labeling on longitudinal tubules (arrowheads) was observed in longitudinal section. (F) Longitudinal sectioning of CAV3 labeling. Note the correspondence of NCX and CAV3 in longitudinal elements. Scale bars = 5 μm.

NCX distribution on the t-system and its relationship to RyR clusters

In a transverse section near a single Z-disk, NCX labeling followed a pattern that seemed to follow the t-system (Fig. 3A). This was confirmed by double labeling with CAV3 as a t-system marker (Fig. 3B). Closer inspection (Fig. 3C) showed brighter puncta of NCX labeling at a fairly uniform lateral spacing of 0.67 ± 0.09 μm along the t-tubules (mean ± SD, n = 5 cells) with less intense staining between puncta on the remainder of the t-system. Comparison with the distribution of CAV3 area shows that the punctate distribution of NCX does not merely reflect the nonlinear interaction of the microscope PSF with labeled tubules (3) (Fig. 3D). The partially punctate nature of labeling was also seen in longitudinal images (Fig. 3E), although correct interpretation of punctate labeling in such images is further compromised by the poorer microscopic Z-resolution (and the PSF-geometric problem noted earlier). There was also NCX labeling between Z-lines in locations where longitudinal t-tubules are located (as identified by corresponding CAV3 labeling; see Fig. 3F).

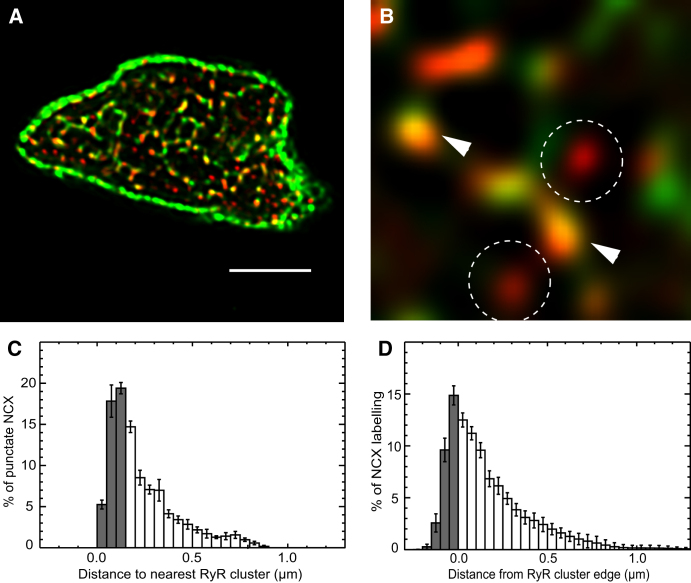

Because the distance between NCX puncta was similar to the distance between RyR clusters (30) simultaneous labeling of RyRs and NCX was carried out to examine the strength of colocalization between these proteins. Overlay of NCX and RyR labeling near a single Z-disk (Fig. 4A) shows that many NCX puncta were located close to RyR clusters, but their overlap was imperfect. In addition, some RyR clusters had only low-intensity (Fig. 4B, arrowheads) or no (Fig. 4B, circles) NCX labeling associated with them. In longitudinal confocal sections NCX labeling was also present on the axial tubules, sometimes overlapping with axially located RyR clusters (Fig. S2).

Figure 4.

Colocalization analysis of NCX and RyR in rat ventricular myocytes. (A) A transverse view of a cell labeled for NCX (green) and RyR (red), obtained by a 1 μm maximum intensity projection near a single Z-line. (B) In a magnified view some RyR clusters can be seen to coincide with the bright NCX puncta (white arrowheads), whereas some RyR clusters were associated with no detectable NCX label (dashed circles). (C) A histogram of distances between centers of NCX puncta and RyR clusters. The gray bars indicate distances are considered to be colocalized (i.e., <150 nm). (D) A histogram of the percentage of total NCX labeling as a function of the Euclidean distance from the edge of the nearest RyR cluster. Note this different distance algorithm yields a similar distance dependence. The shaded bars indicate the fraction of labeling found within the RyR mask. Scale bar = 5 μm.

Quantification of these data were carried using the centroid analysis method (Fig. 4C). The histogram of centroid distances had a mode at 100–150 nm and from this data we can calculate that ∼42% of the RyR clusters were within 150 nm of NCX puncta (see Table 1). Analysis of all NCX labeling (i.e., punctate as well as extended labeling) was carried out to measure the distribution of NCX protein relative to the RyR clusters (Fig. 4D). From this analysis it is apparent that ∼27% of all NCX label is within 150 nm of the center of an RyR cluster. These data are consistent with the idea that the NCX puncta are preferentially located near RyR clusters whereas more extended NCX labeling is generally further away. A similar analysis was conducted to quantify the distances of RyR clusters from NCX (both puncta and extended labeling) and is shown in Fig. S2, A and B. From these distributions we calculated that 42% of the RyR clusters were colocalized with NCX puncta (increasing to 55% when extended NCX labeling was included); ∼45% of the total NCX labeling was concentrated in puncta, and these could be viewed as sites of concentrated Ca2+ entry or extrusion.

Table 1.

Colocalizing fractions of NCX and CAV3 with RyR and of RyR with NCX and CAV3 (mean ± SD)

| Protein A | % of protein A labeling colocalizing with RyR clusters | % of RyR cluster centroids (weighted by their relative intensities) colocalizing with protein A | Cells (n) | Animals (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCX (t-tubular)∗ | 34.91 ± 5.99 | 41.73 ± 8.64 | 6 | 3 |

| NCX (t-tubular)† | 27.33 ± 2.22 | 55.17 ± 4.89 | 6 | 3 |

| CAV3 (t-tubular)† | 14.89 ± 2.59 | 13.99 ± 3.72 | 5 | 2 |

| NCX (surface)† | 26.62 ± 1.96 | 28.75 ± 2.20 | 5 | 2 |

All puncta, weighted by their relative intensities, detected within a 150-nm distance of the nearest punctum of the second channel were considered colocalized.

First column shows the fraction of the total NCX/CAV3 labeling found within the RyR binary mask. The second column indicates the percentage of RyR labeling detected within the NCX/CAV3 binary mask.

Distribution of RyRs and NCX on the surface sarcolemma

Areas of the cell surface in direct contact with the coverslip were readily visualized using TIRF microscopy. In these regions, we observed a band-like arrangement of clusters of RyR labeling. Typically, each band was composed of an (irregular) double row of RyR clusters as reported previously (29). When overlaid with a widefield epifluorescence images, the double rows of surface junctions were centered on the single rows of deeper Z-line associated RyRs as shown in Fig. 5A (with a mean distance from a surface RyR cluster to the nearest Z-line of ∼350 nm). High-resolution images (Fig. 5B) showed that the RyR clusters were not simply circular, a conclusion reinforced by 2D deconvolution (Fig. 5B, right panel). These RyR clusters had highly variable geometry, with long axes approaching 400 nm. In addition, apparent size was poorly correlated with the integrated optical density within the cluster (r ∼ 0.2). This suggests that the peripheral junctions are incompletely filled with RyRs. The RyR nearest neighbor distances on the outer sarcolemma had a mean of 0.75 ± 0.12 μm and the surface density of clusters determined from the TIRF data were 0.57 ± 0.10 clusters/μm2 (n = 5 cells).

Figure 5.

RyR and NCX labeling at the surface sarcolemma visualized using TIRF microscopy. (A) Double rows of peripheral RyR clusters (red) seen in the TIRF image typically flanked the single row of RyR seen in a widefield image of the cell interior (cyan). (B) High magnification view of peripheral RyR clusters. The left panel shows raw TIRF data acquired at 70 nm/pixel sampling and the right panel the same data after deconvolution. The deconvolution data were upsampled onto a 35 nm pixel grid to maintain adequate Nyquist sampling. Note the noncircular shapes of these peripheral RyR clusters. (C) An overlay of NCX (green) and RyR (red) labeling illustrates the dense arrangement of NCX puncta in relation to the rows of RyR extending vertically across the image. (D) A magnified region of C illustrates that bright NCX puncta and RyR clusters tend to overlap (large arrowheads). Weaker NCX and RyR labeling appear less tightly linked (small arrowheads).(E) The histogram of the percentage of the punctate NCX labeling plotted as a function of the distance from the nearest RyR cluster exhibits a colocalizing fraction of ∼27% (gray bars). (F) The ratio between the percentage of labeling and the percentage of membrane area is shown as a function of the distance from the edge of the nearest RyR cluster (illustrated with broken lines in D). This illustrates the effectively higher density of NCX labeling within and around the RyR clusters. Scale bars = A, 4 μm; C, 2 μm.

Fig. 5C shows TIRF images of NCX (green) and RyR labeling (red) on the cell surface. Typically, puncta of NCX labeling had a diffraction-limited FWHM diameter of 250–270 nm with a large range of intensities. Fig. 5D shows a novel feature of the surface membrane relationship between RyR and NCX labels. As shown by the large arrows, high intensity NCX labeling tended to at least partially overlap with RyR clusters. Regions of weaker NCX labeling did not coincide with RyR labeling (small arrows). Analysis of the distance of NCX puncta to the edge of RyR clusters (Fig. 5E) shows that ∼27% of NCX colocalized with RyRs. Fig. 5F shows the density of NCX labeling (i.e., the ratio between the fraction of labeling and the fraction of local membrane area) as a function of the distance from the edge of the nearest RyR cluster. The density of NCX labeling decayed monotonically with distance from the center of RyRs, confirming the visual impression obtained from Fig. 5D. In addition, ∼29% of the peripheral RyR clusters were found in overlap with punctate NCX labeling (not shown).

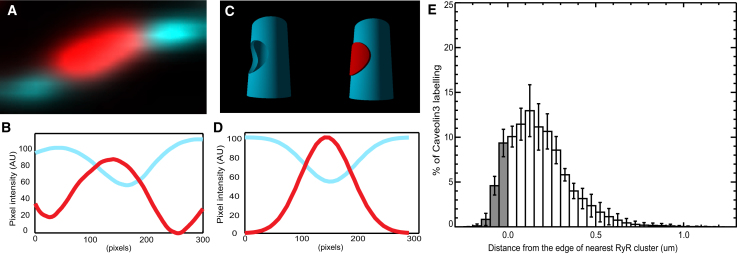

Relationship of CAV3 labeling to RyR clusters

In CAV3-RyR double-labeled micrographs, the CAV3 labeling appeared weaker in the immediate vicinity of RyR clusters. On average, the CAV3 labeling intensity at RyR puncta was 54.1 ± 3.7% (n = 5 cells) of its mean overall labeling intensity along the remainder of the t-system (Fig. 6, A and B). Based on a simulated geometry in which CAV3 is approximately uniformly distributed on the t-tubule (250 nm in diameter) but excluded from junctions (300 nm wide; see Fig. 6C) we calculated that the apparent CAV3 labeling intensity in confocal micrographs would drop to ∼60% of the t-system associated value at the center of a junction (due to blurring by the confocal PSF) as shown in Fig. 6D. The anti-correlated pattern of RyR and CAV3 staining is further reflected in a histogram profiling the total labeling intensity of CAV3 as a function of the three-dimensional Euclidean distance from the edge of a given RyR cluster (Fig. 6E). Note that, in contrast to NCX labeling, only 14.9 ± 2.6% of the total CAV3 labeling is within the RyR mask, and the mode of the CAV3 distance histogram is located at a considerable distance from RyR cluster edges (150 nm). These observations suggest that CAV3 is largely excluded from RyR junctions.

Figure 6.

Analysis of CAV3 and RyR labeling. (A) A high magnification view of CAV3 labeling near an RyR cluster shows the lower intensity of CAV3 fluorescence at the location of a RyR cluster. (B) An intensity profile along the t-tubule shows that the CAV3 labeling drops to ∼55% in the region of RyR labeling. (C) Model geometry used to calculate the expected drop in CAV3 intensity if no CAV3 is present in the RyR cluster. The model t-tubule (with a diameter of 250 nm) contains uniformly distributed CAV3 (cyan) that is excluded from a 300 nm wide circular patch of RyR labeling (red). (D) The calculated intensity profile along the t-tubule (after blurring the model with the confocal PSF) shows a drop similar to that observed in B. (E) A histogram showing the percentage of CAV3 labeling as a function of the Euclidean distance from the edge of the nearest RyR cluster. The fraction considered as colocalized is shown in gray.

Discussion

Imaging the t-system and RyR clusters

CAV3 that is highly expressed in the outer sarcolemma and the t-system (28, 32) was used as a marker of the cell membranes of ventricular myocytes. The idea that CAV3 stains the complete t-system is supported by our observation that other membrane proteins stain the same areas, in particular NCX and CAV3 extend closely along the same apparent t-tubular connections (compare also Fig. 3). A highly interconnected membrane network was observed near the Z-line when cells were imaged transversely. This architecture is consistent with that seen in previous studies of the t-system (3, 33, 34) and included longitudinal elements similar to those observed in living cells stained with lipophilic membrane dyes (35) and extracellular tracers (3).

Most RyR clusters were, as expected, closely associated with the t-system, but a subpopulation of RyR clusters (∼16%) were >250 nm from the nearest tubule and thus unlikely to be associated with a dyadic junction. These extra-junctional clusters were located at Z-disks and could be clearly identified in transverse confocal sections but might be missed in longitudinal confocal sections (due to the strong Z-disk blurring; Fig. 1C). Similar CAV3-RyR double labeling experiments in tissue sections from perfusion-fixed rat ventricles (see Fig. S1) showed the same proportion of clusters distal to t-tubules (∼16%). This similarity makes it unlikely that these nonjunctional RyR clusters had been orphaned from a loss of t-system after cell isolation (36). It is possible that some of the nonjunctional RyR clusters correspond to electron-dense areas in corbular SR seen in electron microscopy studies (37, 38). Alternatively, these RyR clusters might be migrating to/from junctions or reflect dynamic remodeling of the t-system. The functional role of the extra junctional RyR clusters is uncertain, and although it seems unlikely that release from these clusters would be triggered directly by the calcium current (ICa), they are sufficiently close to t-system associated RyR clusters (∼0.6 μm center-to-center) to allow CICR when neighboring couplons fire (39).

We also detected a small proportion of RyR clusters outside the Z-disks at various positions along the sarcomere. Contrary to the view of Lukyanenko et al. (40) virtually all of these clusters colocalized with longitudinal tubules and we suggest that these RyRs are in junctions on the longitudinal t-system. The observation of RyR clusters associated with longitudinal tubules could be relevant in helping explain the spread of regenerative Ca2+ waves between sarcomeres. Using mathematical models of Ca2+ wave propagation it was noted that at typical sarcomere length (∼2 μm) wave propagation between sarcomeres appeared problematic (41). The presence of RyR clusters between sarcomeres would therefore facilitate propagation by their saltatory activation. However, given their low density (1.6% of total clusters), it seems more likely that the nonplanar architecture of the Z-disks and the dislocations in the RyR distribution and Z-disk structure is more important for intersarcomere wave propagation (42). It has been noted that there is an increased prevalence of longitudinal tubules in heart failure (36, 43) but it is unclear if this remodeling of the t-system is associated with an increased presence of RyR clusters between Z-disks. Our finding of RyR clusters along longitudinal tubules suggest that this is possible, and if so, would contribute to the risk of Ca2+ wave development in heart failure.

Distribution of peripheral RyR clusters

Double rows of RyR clusters were observed on the surface sarcolemma, morphologically similar to those described by Chen-Izu et al. (29). The mean distance to the Z-line was ∼0.35 μm with an overall density of 0.57 couplons/μm2. However, it should be noted that this area measure is based on the assumption that the surface membrane is flat. Nevertheless, in a 30-pL cell, ∼13% of all RyR clusters would be peripheral (3821 peripheral couplons compared to a total of ∼29,000). Although the largest peripheral RyR clusters were above the resolution limit of the microscope, this does not allow a simple interpretation of how many RyRs might be present. This problem arises from our observation that i), RyR clusters had variable shapes; and ii), variable integrated intensity within equal areas that were not explained completely by the predicted variability arising from photon noise or variation in antibody binding. Conservatively assuming an effective antibody binding efficiency of 40% variation in binding should be ∼12% if at least 100 receptors are in a cluster (based on the bionomial distribution). The variations due to photon noise were generally <1% whereas the integrated intensity in similar sized RyR puncta varied by >100%. The simplest interpretation of these observations would be that the microscopic image reflects a more complex underlying structure in which RyRs are not tightly packed within the imaged area. In a previous study (30), we calculated the size of junctions on t-tubules assuming that junctions are circular. We could not directly test this assumption due to the complex interaction of the PSF with junctions in 3D and the observed intensity variations were consistent with resulting from random junction orientation. TIRF microscopy allowed us to image peripheral junctions in two dimensions and removed the uncertainty about junction orientation. If RyRs are not tightly packed then the number of RyRs in peripheral junctions is likely smaller than suggested by the apparent RyR punctum area and higher resolution data is needed to provide improved size estimates.

Distribution of NCX within the t-system and outer sarcolemma

The morphology of NCX labeling observed in longitudinal confocal sections was similar to that observed in previous studies (20, 44, 45). However, the detailed distribution of NCX within the t-system has remained unclear because the confocal PSF emphasizes tubule segments oriented along the optical axis that leads to a punctate morphology even if none exists (see also Fig. 1C). Imaging single cells end-on avoids this problem and shows that the NCX labeling pattern is extensive and consists of a relatively uniform background with concentrated patches (we have called puncta) in both t-tubules and outer sarcolemma. Although there were quantitative differences the fraction of RyR clusters that contained NCX label (p < 0.001) between t-tubules and the outer sarcolemma, there was no difference (p = 0.59, df = 9 cells) in the amount of NCX label associated with RyR clusters in these regions. In connection with this point, we note that RyR organization on the outer surface is quite different from that of the interior of the cell with RyRs forming some double rows and separated by ∼0.75 μm compared to the clusters within the cell that are separated by ∼0.6 μm. The double rows occur at the Z-line spacing so that the distance between RyR clusters increases again (to ∼1.1 μm) between Z-lines, showing a markedly nonuniform distribution of RyR clusters on the cell surface. This is quite different from the more or less isotropic distribution of RyRs within the cell.

In contrast to CAV3 labeling, NCX labeling intensity did not detectably decrease at the site of RyR clusters and many of the intense puncta were on top of (or very close to) RyR clusters. This suggests that NCX was not excluded from junctions. On the other hand, we also saw no evidence that NCX was exclusively concentrated at junctions and the mean distance of the NCX puncta (0.25 ± 0.03 μm) to the nearest RyR cluster was slightly closer than would be expected from a purely random distribution of NCX puncta along t-tubules.

The location of CAV3 in relation to RyRs and NCX

Our finding of the poor colocalization of the caveolar marker CAV3 with RyRs is consistent with EM data from rabbit myocardium showing an absence of caveolae at the junctional t-tubular membrane (32). Our simulation of a CAV3 distribution on t-tubular membranes that is excluded from junctions showed that the observed drop in the CAV3 labeling intensity above RyR clusters is consistent with the complete absence of CAV3 from junctions. The colocalization analysis using an RyR mask still classified ∼15% of the CAV3 fluorescence as colocalized. This fraction results from the blurring of subresolution structures by the confocal microscope. Interestingly, when we measured the fraction of CAV3 colocalizing with RyR in confocal data taken in longitudinal section of the cell interior the colocalization was increased to ∼40% (due to stronger axial blurring in confocal data), a value similar to that reported previously (27). This confirms the importance of resolution for colocalization studies (46) and shows the improvement made by imaging single cells end on (29). In broad agreement with previous work in the rat (28), our data supports the idea that there is no strong correlation between NCX and CAV3 labeling (we calculated a Pearson's correlation coefficient of 0.26) because NCX labeling contained puncta whereas the CAV3 labeling was largely uniform outside RyR clusters.

Consequences for cardiac E-C coupling

NCX within (or close to) the dyadic junction is in a location where it may have a profound effect on E-C coupling by modifying local Ca2+ transport. During the early phase of the action potential NCX can work in the reverse mode (18, 19, 47) and thereby contribute to the Ca2+ trigger for CICR. This contribution could be either direct (17, 19) or contribute a Ca2+ influx to augment Ca2+ entry via DHPRs to synergistically increase the ability of ICa to trigger CICR. Evidence for such a synergistic interaction has been shown in rabbit ventricular myocytes (22) and rat (24) (although the effect in rat seemed to depend on stimulation with cAMP). The details of the synergies between ICa and NCX remain unclear; for example, it is possible that local Ca2+ may activate NCX via a catalytic effect (18, 48) or the local increase in Ca2+ could reduce the thermodynamic gradient for Ca2+ entry via NCX. Furthermore, due to the nonlinear dependence of E-C coupling on trigger Ca2+, addition of a NCX component to that of ICa might appear disproportionately large when compared to the situation when ICa is blocked (when the direct trigger by NCX would appear small). Finally, NCX could make E-C coupling more robust by providing a backup should the primary trigger be reduced (25).

The NCX labeling data presented here allows for all of the above possibilities, although revision of some modeling work may be required to take account of the nonuniform distribution of NCX that we observe. In connection with this point, we have included detailed analyses of the spatial distributions of NCX relative to RyR clusters to allow more refined models to be constructed.

In the surface membrane, more intense NCX puncta were closer to RYR clusters than would be expected by chance. Our data suggests a similar relationship in the t-system but it was more subtle due to the more complicated geometry of the t-system (and interaction of that geometry with the PSF). It seems reasonable to assume that NCX located far from junctions would subsume a purely Ca2+ extrusion role whereas NCX near junctions could provide both Ca2+ entry and extrusion. For a linear dependence of Ca2+ extrusion on local Ca2+ (as assumed by most models), the location of NCX with respect to junctions should be relatively unimportant. If this is the case, then it suggests that locating NCX in puncta may be more important for (or related to) a Ca2+ entry function. We suggest that placing NCX in puncta would allow Ca2+ entry via NCX to catalytically increase the activity of fellow members of the NCX cluster to provide a form of positive feedback or autocatalytic effect. Such feedback might also ‘prime’ the cluster for subsequent Ca2+ extrusion. These effects would be maximized by constructing dense clusters, compatible with the bright NCX puncta we observe.

Conclusion

We have analyzed the distribution of NCX in the t-system and on the outer sarcolemma of rat cardiac myocytes. NCX labeling was both punctate and extended along the t-system and this labeling was related to the presence of RyR clusters. The heterogeneous expression pattern of NCX across the sarcolemma suggests that NCX may simultaneously operate in different modes with different functions depending on location in the membrane (including t-system). The distance based histogram data provided here can be used to calculate updated colocalization measures if RyR junction size estimates become revised (e.g., by electron tomographic analysis).

Editor: David A. Eisner.

Footnotes

Methods, four figures, and references are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(09)01423-4.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Cannell M.B., Cheng H., Lederer W.J. The control of calcium release in the heart muscle. Science. 1995;268:1045–1049. doi: 10.1126/science.7754384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franzini-Armstrong C., Protasi F., Ramesh V. Shape, size, and distribution of Ca2+ release units and couplons in skeletal and cardiac muscle. Biophys. J. 1999;77:1528–1539. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77000-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soeller C., Cannell M.B. Examination of the transverse-tubular system in living cardiac rat myocytes by 2-photon microscopy and digital image-processing techniques. Circ. Res. 1999;84:266–275. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fawcett D.W., McNutt N.S. The ultrastructure of the cat myocardium I: ventricular papillary muscle. J. Cell Biol. 1969;42:1–45. doi: 10.1083/jcb.42.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sommer J.R., Johnson E.A. Cardiac muscle. A comparative study of Purkinje fibers and ventricular fibers. J. Cell Biol. 1968;36:497–526. doi: 10.1083/jcb.36.3.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fabiato A. Calcium -induced release of calcium from the cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Am. J. Physiol. 1983;245:C1–C14. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1983.245.1.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Langer G.A., Peskoff A. Calcium concentration and movement in the diadic cleft space of the cardiac ventricular cell. Biophys. J. 1996;70:1169–1182. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79677-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soeller C., Cannell M.B. Numerical simulation of local calcium movements during L-type calcium channel gating in the cardiac diad. Biophys. J. 1997;73:97–111. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78051-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stern M.D. Theory of excitation-contraction coupling in cardiac muscle. Biophys. J. 1992;63:497–517. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81615-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wier W.G., Egan T.M., Lopez-Lopez J.R., Balke C.W. Local control of excitation-contraction coupling in rat heart cells. J. Physiol. 1994;474:463–471. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cannell M.B., Cheng H., Lederer W.J. Spatial non-uniformities in [Ca2+]i during excitation-contraction coupling in cardiac myocytes. Biophys. J. 1994;67:1942–1956. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80677-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scriven D.R.L., Dan P., Moore D.W. Distribution of proteins implicated in excitation-contraction coupling in rat ventricular myocytes. Biophys. J. 2000;79:2682–2691. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76506-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carl S.L., Felix K., Caswell A.H., Brandt N.R., Ball W.J., Jr., et al. Immunolocalization of sarcolemmal dihydropyridine receptor and sarcoplasmic reticular triadin and ryanodine receptor in rabbit ventricle and atrium. J. Cell Biol. 1995;129:673–682. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.3.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun X.-H., Protasi F., Takagishi M., Takeshima H., Ferguson D.G., et al. Molecular architecture of membranes involved in excitation-contraction coupling of cardiac muscle. J. Cell Biol. 1995;129:659–671. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.3.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crespo L.M., Grantham C.J., Cannell M.B. Kinetics, stoichiometry and role of the Na-Ca exchange mechanism in isolated cardiac myocytes. Nature. 1990;345:618–621. doi: 10.1038/345618a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bridge J.H.B., Smolley J.R., Spitzer K.W. The relationship between charge movements associated with ICa and INa-Ca in cardiac myocytes. Science. 1990;248:376–378. doi: 10.1126/science.2158147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldhaber J.I., Lamp S.T., Walter D.O., Garfinkel A., Fukumoto G.H., et al. Local regulation of the threshold for calcium sparks in rat ventricular myocytes: role of sodium-calcium exchange. J. Physiol. 1999;520:431–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00431.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grantham C.J., Cannell M.B. Ca2+ influx during the cardiac action potential in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Circ. Res. 1996;79:194–200. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levi A.J., Spitzer K.W., Kohmoto O., Bridge J.H. Depolarization-induced Ca entry via Na-Ca exchange triggers SR release in guinea pig cardiac myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;266:H1422–H1433. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.4.H1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas M.J., Sjaastad I., Anderson K., Helm P.J., Wasserstrom J.A., et al. Localization and function of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in normal and detubulated rat cardiomyocytes. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2003;35:1325–1337. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trafford A.W., Diaz M.E., O'Neill S.C., Eisner D. Comparison of subsarcolemmal and bulk calcium concentration during spontaneous calcium release in rat ventricular myocytes. J. Physiol. 1995;488:577–586. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sobie E., Cannell M.B., Bridge J.H.B. Allosteric activation of Na+-Ca2+ exchange by L-type Ca2+ current augments the trigger flux for SR Ca2+ release in ventricular myocytes. Biophys. J. 2008;94:L54–L56. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.127878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lines G.T., Sande J.B., Louch W.E., Mork H.K., Grottum P., et al. Contribution of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger to rapid Ca2+ release in cardiomyocytes. Biophys. J. 2006;91:779–792. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.072447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Viatchenko-Karpinski S., Terentyev D., Jenkins L.A., Lutherer L.O., Gyorke S. Synergistic interactions between Ca2+ entries through L-type Ca2+ channels and Na+-Ca2+ exchanger in normal and failing rat heart. J. Physiol. 2005;567:493–504. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.091280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sher A.A., Noble P.J., Hinch R., Gavaghan D.J., Noble D. The role of the Na+/Ca2+ exchangers in Ca2+ dynamics in ventricular myocytes. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2008;96:377–398. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dibb K.M., Graham H.K., Venetucci L.A., Eisner D.A., Trafford A.W. Analysis of cellular calcium fluxes in cardiac muscle to understand calcium homeostasis in the heart. Cell Calcium. 2007;42:503–512. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scriven D.R.L., Klimek A., Asghari P., Bellve K., Moore E.D.W. Caveolin-3 is adjacent to a group of extradyadic ryanodine receptors. Biophys. J. 2005;89:1893–1901. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.064212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cavalli A., Eghbali M., Minosyan T.Y., Stefani E., Phillipson K.D. Localization of sarcolemmal proteins to lipid rafts in the myocardium. Cell Calcium. 2007;42:313–322. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen-Izu Y., McCulle S., Ward C.W., Soeller C., Allen B.G., et al. Three-dimensional distribution of ryanodine receptor clusters in cardiac myocytes. Biophys. J. 2006;91:1–13. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.077180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soeller C., Crossman D.J., Gilbert R., Cannell M.B. Analysis of ryanodine receptor clusters in rat and human cardiac myocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:14958–14963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703016104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin E., Hung V.H., Kashihara H., Dan P., Tibbits G. Distribution patterns of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger and caveolin-3 in developing rabbit cardiomyocytes. Cell Calcium. 2009;45:369–383. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levin K.R., Page E. Quantitative studies on plasmalemmal folds and caveolae of rabbit ventricular myocardial cells. Circ. Res. 1980;46:244–255. doi: 10.1161/01.res.46.2.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Forssmann W.G., Girardier L. A study of the t system in rat heart. J. Cell Biol. 1970;44:1–19. doi: 10.1083/jcb.44.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forbes M.S., Hawkey L.A., Sperelakis N. The transverse-axial tubular system (tats) of mouse myocardium: Its morphology in the developing and adult animal. Am. J. Anat. 1984;170:143–162. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001700203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brette F., Komukai K., Orchard C.H. Validation of formamide as a detubulation agent in isolated rat cardiac cells. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2002;283:H1720–H1728. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00347.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song L.-S., Sobie E., McCulle S., Lederer W.J., Balke C.W., et al. Orphaned ryanodine receptors in the failing heart. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:4305–4310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509324103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jorgensen A.O., Shen A.C.-Y., Campbell K.P. Ultrastructural localization of calsequestrin in adult rat atrial and ventricular muscle cells. J. Cell Biol. 1985;101:257–268. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.1.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jorgensen A.O., Shen A.C.-Y., Arnold W., McPherson P.S., Campbell K.P. The Ca2+-release channel/ ryanodine receptor is localized in junctional and corbular sarcoplasmic reticulum in cardiac muscle. J. Cell Biol. 1993;120:969–980. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.4.969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramay, H.R., E.A. Sobie, W.J. Lederer, and M.S. Jafri. 2007. A Monte Carlo simulation study of spontaneous calcium waves in the heart. 2007 Biophysical Society Meeting Abstracts, Biophysical Journal, Supplement, 257a, Abstract.

- 40.Lukyaneko V., Ziman A., Lukyaneko A., Salnikov V., Lederer W.J. Functional groups of ryanodine receptors in rat ventricular cells. J. Physiol. 2007;583:251–269. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.136549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Izu L.T., Means S.A., Shadid J.N., Chen-Izu Y., Balke C.W. Interplay of ryanodine receptor distribution and calcium dynamics. Biophys. J. 2006;91:95–112. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.077214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soeller C., Jayasinghe I., Li P., Holden A.V., Cannell M.B. Three-dimensional high-resolution imaging of cardiac proteins to construct models of intracellular Ca2+ signaling in rat ventricular myocytes. Exp. Physiol. 2009;94:496–508. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2008.043976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Louch W.E., Mork H.K., Sexton J., Stromme T.A., Laake P., et al. T-tubule disorganization and reduced synchrony of Ca2+ release in murine cardiomyocytes following myocardial infarction. J. Physiol. 2006;572:519–533. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.107227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kieval R.S., Bloch R.J., Lindenmayer G.E., Ambesi A., Lederer W.J. Immunofluorescence localization of the Na-Ca exchanger in heart cells. Am. J. Physiol. 1992;263:C545–C550. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.263.2.C545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frank J.S., Mottino G., Reid D., Molday R.S., Phillipson K.D. Distribution of the Na+-Ca2+ exchange protein in mammalian cardiac myocytes: an immunofluorescence and immunocolloidal gold-labeling study. J. Cell Biol. 1992;117:337–345. doi: 10.1083/jcb.117.2.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sedarat F., Lin E., Moore E.D.W., Tibbits G.F. Deconvolution of confocal images of dihydropyridine and ryanodine receptors in developing cardiomyocytes. J. Appl. Physiol. 2004;97:1098–1103. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00089.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weber C.R., Ginsburg K.S., Bers D.M. Cardiac submembrane [Na+] transients sensed by Na+-Ca2+ exchange current. Circ. Res. 2003;92:950–952. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000071747.61468.7F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hilgemann D.W., Collins A., Matsuoka S. Steady-state and dynamic properties of cardiac sodium-calcium exchange. Secondary modulation by cytoplasmic calcium and ATP. J. Gen. Physiol. 1992;100:933–961. doi: 10.1085/jgp.100.6.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.