Abstract

A combination of lipid monolayer- and bilayer-based model systems has been applied to explore in detail the interactions between and organization of palmitoylsphingomyelin (pSM) and the related lipid palmitoylceramide (pCer). Langmuir balance measurements of the binary mixture reveal favorable interactions between the lipid molecules. A thermodynamically stable point is observed in the range ∼30–40 mol % pCer. The pSM monolayer undergoes hyperpolarization and condensation with small concentrations of pCer, narrowing the liquid-expanded (LE) to liquid-condensed (LC) pSM main phase transition by inducing intermolecular interactions and chain ordering. Beyond this point, the phase diagram no longer reveals the presence of the pSM-enriched phase. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) of multilamellar vesicles reveals a widening of the pSM main gel-fluid phase transition (41°C) upon pCer incorporation, with formation of a further endotherm at higher temperatures that can be deconvoluted into two components. DSC data reflect the presence of pCer-enriched domains coexisting, in different proportions, with a pSM-enriched phase. The pSM-enriched phase is no longer detected in DSC thermograms containing >30 mol % pCer. Direct domain visualization has been carried out by fluorescence techniques on both lipid model systems. Epifluorescence microscopy of mixed monolayers at low pCer content shows concentration-dependent, morphologically different pCer-enriched LC domain formation over a pSM-enriched LE phase, in which pCer content close to 5 and 30 mol % can be determined for the LE and LC phases, respectively. In addition, fluorescence confocal microscopy of giant vesicles further confirms the formation of segregated pCer-enriched lipid domains. Vesicles cannot form at >40 mol % pCer content. Altogether, the presence of at least two immiscible phase-segregated pSM-pCer mixtures of different compositions is proposed at high pSM content. A condensed phase (with domains segregated from the liquid-expanded phase) showing enhanced thermodynamic stability occurs near a compositional ratio of 2:1 (pSM/pCer). These observations become significant on the basis of the ceramide-induced microdomain aggregation and platform formation upon sphingomyelinase enzymatic activity on cellular membranes.

Introduction

Sphingosine-based lipids are well-known modulators of cell membrane physical properties. Since the sphingolipid signaling pathway was brought to light (1,2), these lipids have gained massive attention as key players in various signaling and trafficking processes (3–5). It has been proposed, specifically, that ceramide generation upon sphingomyelinase enzymatic activity induces highly ordered segregated lateral structures with different intermolecular packing, which could regulate the proposed membrane platform constitution before lipid-mediated cell signaling (6–10).

Sphingomyelin is the major sphingolipid present in the outer leaflet of cell plasma membranes, its fatty acid composition consisting mostly of long saturated chains (C16, C18, and C24). Consequently, sphingomyelinase-generated N-acylsphingosines (ceramides) in the plasma membrane will be mainly composed of the same saturated acyl chains. The physical properties of ceramide interaction with phospholipids have been extensively studied in model systems over the past years, revealing important effects on membrane permeability (11,12), transbilayer flip-flop lipid motion (13), and lateral domain segregation (14–16). Ceramide-induced domain segregation in lipid model membranes has been observed for several lipid mixtures with phospholipids (14–21), using very different biophysical approaches (see (22,23) for reviews). Ceramides have been observed to induce high-temperature melting domains in mixtures where phospholipids display low (palmitoyl-oleoyl-phosphatidylcholine) (17) and high (dipalmitoyl-phosphatidylcholine or dielaidoyl-phosphatidylethanolamine) (15,18) gel-fluid phase transition temperature. Recently, a microscopy study combining differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), fluorescence spectroscopy, and confocal fluorescence of the interaction of ceramide with its relative sphingomyelin showed the segregation of detergent-resistant, ceramide-enriched domains for the egg natural sphingolipid source mixture (all saturated chains with 84 mol % palmitoyl residues) (19). Ceramide-enriched domain segregation in mixtures with sphingomyelin has been well characterized by Maggio and co-workers based on Langmuir balance studies. In either premixed or enzyme-generated systems with bovine brain sphingomyelin (mainly stearic (18:0) and lignoceric (24:0) acyl chains), ceramide induces morphologically different ceramide-enriched domains, depending on how the mixture was generated (20,24,25). Acyl chain heterogeneity of commercially available lipid natural mixtures must be taken into account when looking at lateral segregation. In this respect, saturated acyl chains are associated with a stronger interaction with the phospholipid and generation of ordered lipid domains. Acyl chain length should be of importance as well, as it can also affect membrane physical properties (18,26). It has been observed that differences in acyl chain length induce membrane interdigitation (21,27) and are the cause of some cases of phase separation. However, similar results based on differential scanning calorimetry for vesicles containing natural ceramides of different length do not support this assumption (16).

To understand the organization of a pure, chemically defined sphingomyelin/ceramide mixture, a combination of monolayer and bilayer lipid model membranes has been applied to characterize the intermolecular packing of the physiologically relevant C16-palmitoylsphingomyelin (pSM) and its associated C16-palmitoylceramide (pCer). The various experimental techniques converge in showing a picture of at least two immiscible, phase-segregated pSM-pCer mixtures of different composition and phase state when the mole fraction of pCer is in the range 0–0.4.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

Palmitoyl sphingomyelin (pSM) and palmitoyl ceramide (pCer) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). The lipophilic fluorescent probe 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate (DiIC18) was purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). All lipids were >99% pure by thin-layer chromatography and were used without further purification. Solvents and chemicals were of the highest commercial purity available. The water was purified by a Milli-Q (Millipore, Billerica, MA) system, to yield a product with a resistivity of ∼18.5 MΩ/cm and absence of surface-active impurities routinely checked as described elsewhere (28).

Monolayer compression isotherms

Compression-expansion isotherms were obtained for synthetic pSM-pCer in different proportions. Mixed lipid monolayers were spread from premixed solutions in chloroform/methanol (2:1). All measurements were performed at room temperature (26 ± 1°C) in a 90-cm2 compartment of a specially designed circular Monofilmmeter Teflon trough (Mayer Feintechnik, Germany) filled with 80 mL of 145 mM NaCl, pH ∼5.6. Details of the equipment used were described by Carrer and Maggio (15). Surface pressure and surface potential were automatically recorded (Lab-Trax, World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) as a function of the mean molecular area during compression-expansion at a speed of 0.2 nm2 mol−1 min−1. The reproducibility of experiments was within the maximum standard error of ±1 Å2 for molecular areas and ±10 mV for surface potential measurements. All thermodynamic quantities were derived from the measured surface pressure, mean molecular area, and dipole potential and from the theoretical (ideal) values calculated for the mixtures at each proportion using the corresponding experimental values of the pure components.

Epifluorescence monolayer microscopy

All experiments were carried out in an air-conditioned room (23 ± 2°C). The monolayers were doped with 0.5 mol % DiIC18 and were spread from lipid solutions in chloroform/methanol (2:1) over a subphase of 145 mM NaCl until reaching a pressure of <∼0.5 mN/m (29). After solvent evaporation (15 min), the monolayer was slowly compressed (1 Å2 mol−1 min−1) to the desired surface pressure. Epifluorescence microscopy (Zeiss Axiovert, Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) was carried out using a mercury lamp (HBO 50, Osram, München, Germany), a 20× LD objective, a rhodamine filter set, and an all-Teflon zero-order trough (Kibron μ-Trough S, Kibron, Helsinki, Finland) mounted onto the microscope stage. Images with exposure times between 500 and 800 ms were registered with a software-controlled (Axiovision, Zeiss) charge-coupled device camera (Axiocam, Zeiss). Liquid-expanded (LE) and liquid-condensed (LC) lipid phases are represented by bright (high-fluorescence/DiIC18-enriched) and dark (low-fluorescence/DiIC18-depleted) images, respectively (331 × 263 μm). A segmentation of DiIC18-depleted domains was achieved, as described previously (24), by interactive image processing routines written in an IDL (Interactive Data Language, ITT, Boulder, CO) that allows accurate calculation of the area fraction occupied by the coexistent phases.

Calculation of the pCer mole fraction in the LC and LE phases from epifluorescence images

The mole fraction of pCer in the LC phase (XLCpCer) observed by epifluorescence microscopy of pSM-pCer mixed monolayers was calculated assuming that all pCer molecules remain in the LC phase. This assumption is valid only for images that contain >25% dark area. Images of monolayers containing 0.25 mol fraction of pCer showed invariance of the extent of area occupied by the LC phase with surface pressure (81 ± 1%, mean ± SE of 15 values; also see Fig. 6, D and E) and were used to calculate XLCpCer.

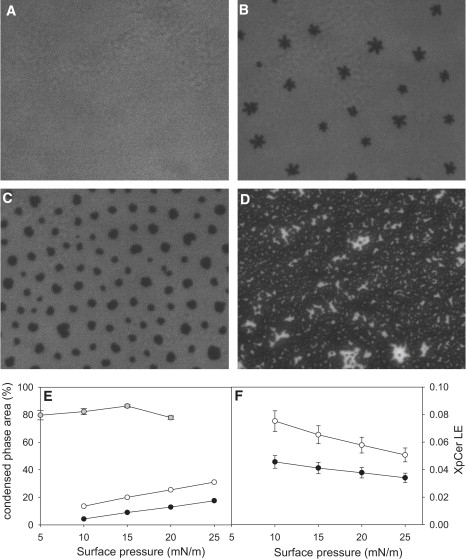

Figure 6.

Epifluorescence micrographs of pSM-pCer monolayers. The figure shows images of pure pSM (A) and mixed pSM-pCer monolayers containing 5 mol % (B), 10 mol % (C), and 25 mol % (D) pCer at 10 mN/m. The monolayers were doped with 0.5 mol % of the fluorescent probe DiI-C18. All images are 331 × 263 μm in size. (E and F) Surface dependency of the LC (dark, probe-depleted) area extent and the pCer mole fraction present in the LE phase (bright, probe-enriched), respectively. The data were calculated from images of mixed monolayers containing 5 mol % (solid circles), 10 mol % (open circles), and 20 mol % pCer (gray circles). Error bars represent the mean ± SE values for E and the propagation error for the calculated values in F.

The mole fraction of pCer in the LC phase is

| (1) |

where is the number of molecules of pSM in the LC phase observed in the image and is the number of molecules of pCer in the analyzed image (by assumption, all molecules are in the LC phase). Those parameters can be expressed at a defined constant surface pressure as

| (2) |

and

| (3) |

where is the total mole fraction of pCer in the monolayer, is the total area in μm2 of the analyzed image, and is the fraction of that image that is occupied by the dark (LC) phase. , , and are the average molecular areas of pCer, and pSM in the LC and LE phase respectively. By substituting Eqs. 3 and 2 in Eq. 1, a polynomial equation of the type

| (4) |

can be constructed with

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

Equation 4 can be solved, as usual, by

| (8) |

giving one root in the 0–1 range.

Further analysis was achieved to investigate the miscibility of pCer in the LE phase (expressed as the mol fraction of pCer present in the LE phase XLEpCer), assuming a constant value of XLCpCer. For this purpose, images showing a large extent (>75%) of LE (bright) phase were analyzed. Then, the number of molecules of pCer in the analyzed image is calculated as

| (9) |

where the numbers of pCer molecules in the LC and LE phases at a constant surface pressure are, respectively,

| (10) |

and

| (11) |

By substituting Eqs. 10 and 11 in Eq. 9, we can calculate a value for XLEpCer. The final expression is

| (12) |

Differential scanning calorimetry

All measurements were performed in a VP-DSC high-sensitivity scanning microcalorimeter (MicroCal, Northampton, MA). Both lipid and buffer solutions were fully degassed before loading into the appropriate cell. Buffer was 20 mM PIPES, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4. Lipid suspensions were loaded into the microcalorimeter in the form of multilamellar vesicles. The lipids were hydrated in buffer, with dispersion facilitated by stirring with a glass rod, and finally the solutions were extruded through a narrow tubing (0.5 mm internal diameter, 10 cm long) between two syringes 100 times at 75°C, above the transition temperature of the pSM-pCer mixtures. A final amount of 0.5 ml at 0.4 mM total lipid concentration was loaded into the calorimeter, and three heating scans were performed at 45°C/h between 14 and 80°C for all samples. pSM lipid concentration was determined as lipid phosphorus, and used together with data from the third scan, to obtain normalized thermograms. The software Origin 7.0 (MicroCal), provided with the calorimeter, was used to determine the different parameters for the scans. The software GRAMS_32 Spectra Notebase (Galactic Industries, Waltham, MA) was used for curve-fitting.

Confocal microscopy of giant unilamellar vesicles

Giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) were prepared using the electroformation method developed by Angelova et al. (30). For vesicle observation, a chamber supplied by L. A. Bagatolli (Odense, Denmark) was used that allows direct GUV visualization under the microscope (31). Stock lipid solutions (0.2 mg/ml total lipid containing 0.2 mol % DiIC18) were prepared in a chloroform/methanol (2:1 v/v) solution. A 3-μl sample of the appropriate lipid stock was added to the surface of Pt electrodes, and solvent traces were removed by placing the chamber under high vacuum for at least 2 h. The Pt electrodes were covered with 400 μl Millipore-filtered Milli-Q water previously equilibrated at 75°C. The Pt wires were connected to an electric wave generator (TG330 function generator, Thurlby Thandar Instruments, Huntington, United Kingdom) under alternating-current field conditions (10 Hz, 0.9 V) for 2 h at 75°C. The generator and the water bath were switched off and vesicles were left to equilibrate at room temperature for 1 h. After GUV formation, the chamber was placed onto an inverted confocal fluorescence microscope (Nikon D-ECLIPSE C1, Nikon, Melville, NY). The excitation wavelength for DiIC18 was 561 nm, and the images were collected using a bandpass filter of 593 ± 20 nm. Image treatment and quantification were performed using the software EZ-C1 3.20 (Nikon, Melville, NY). No difference in domain size, formation, or distribution was observed in the vesicles during the observation period or after laser exposure.

Results

Interaction of pSM and pCer in mixed monolayers

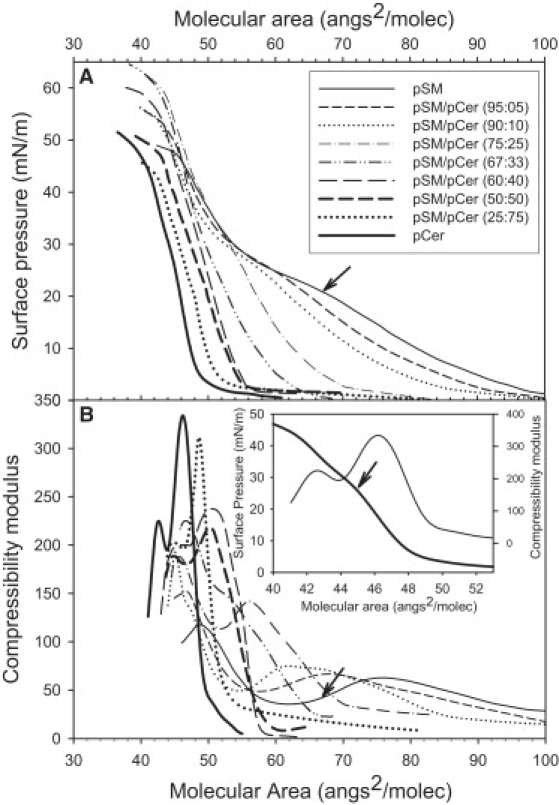

Fig. 1 A shows the surface pressure versus molecular area isotherms for mixtures of pSM-pCer in different proportions. pSM shows an LE-LC phase transition at ∼25 mN/m and ∼60 Å2/mol. The phase transition is indicated by an inflection point (arrow) in the plot of compressibility modulus (κ) versus molecular area (Fig. 1 B). The monolayer behavior of this lipid coincides with that reported by others (32,33). Also, in agreement with previous reports (34), pCer shows an LC phase in the whole range of surface pressures that is evidenced by its high κ value (Fig. 1 B). We have observed an LC-LC rearrangement at ∼23 mN/m and ∼45 Å2/mol that probably corresponds to two types of condensed state adopted by pCer at surface pressures >∼20 mN/m (Fig. 1 B, inset). This transition is maintained in pCer-pSM mixtures as long as the mole fraction of pCer remains >33 mol % (Fig. 1). Condensed state transitions in monolayers have been reported for different fatty acids (35). An increased amount of pCer in the monolayer induces higher values of κ, reflecting a more condensed state, which becomes more evident at XpCer > 0.25.

Figure 1.

Compression isotherms of pSM-pCer mixed monolayers. (A) Surface pressure versus molecular area of representative isotherms for pure pSM (thin solid line), pure pCer (thick solid line), and pSM-pCer mixtures at 5 mol % (thin short-dashed line), 10 mol % (thin dotted line), 25 mol % (thin dot-dashed line), 33 mol % (thin double-dot-dashed line), 40 mol % (thin long-dashed line), 50 mol % (thick short-dashed line), and 75 mol % (thick dotted line) of pCer. The arrow indicates the LE-LC phase transition pressure for pure pSM. (B) Compressibility modulus (κ) versus molecular area for the mixed monolayers indicated in A. The inset shows the dependence of the pure pCer compression isotherm and compressibility modulus on molecular area (note the expanded molecular area scale). Arrowhead indicates LC-LC rearrangement.

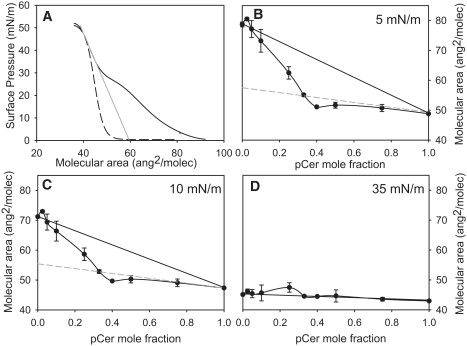

Fig. 2 shows the condensing effect of pCer to be greater than that of pSM at low surface pressures (when pSM is present in the LE phase). This condensation represents mean molecular area reductions of up to 24% and 20% at 5 and 10 mN/m, respectively, with respect to the ideal behavior. Fig. 2, B and C, shows that the mean molecular area of the pSM-pCer mixtures exhibits linear variation, with two different slopes, as a function of the pCer mole fraction, with the lines intersecting at a pCer mole fraction of ∼0.3–0.4. To have an insight into the nature of the condensing effect we considered the extrapolated molecular area of pSM in the LC phase at low surface pressures (Fig. 2 A). The biphasic behavior can be explained as resulting from two ideally mixed, or totally immiscible, components constituted by 1), a mixture of pSM-pCer with XpCer ≈ 0.4 (LC) mixed with pure pSM (LE phase) in the range XpCer = 0–0.4 (where one component is in the LE phase and the other in the LC phase); and 2), a mixture of pSM-pCer with XpCer ≈ 0.4 (LC) mixed with pure pCer over the range XpCer = 0.4–1 (where both components are in the LC phase). This indicates that at XpCer ≈ 0.4, most of the pSM present in the monolayer has undergone an isothermal and isobaric phase transition induced by pCer.

Figure 2.

Condensation of pSM induced by the presence of pCer. (A) Compression isotherms of pure pSM (solid line) and pure pCer (dashed line) and the extrapolated molecular area for pSM in a condensed phase at low surface pressures (straight gray line). (B–D) Variation of mean molecular area of the pSM-pCer mixture with pCer mole fractions at 5, 10, and 35 mN/m, respectively. Solid lines represent the molecular area for an ideal pSM-pCer mixture. Dashed gray lines represent the molecular area for the ideal pSM (in LC phase)-pCer mixture.

At high surface pressures, when pure pSM is in the condensed state, the variation of the average molecular area of the mixtures corresponds to that of either immiscible or ideally mixed films (<5% deviation from ideality), showing no further condensation effect of pCer due to the close packing limit reached by both components, between 40 and 45 Å2/mol (Fig. 2 D).

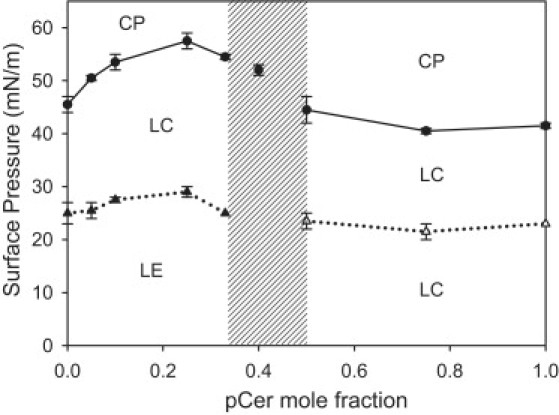

A closer examination of pSM-pCer mixture isotherms shows that, similar to the case for pure pSM, a progressively less marked LE-LC phase transition is present at XpCer in the range 0–0.33 (Figs. 1 and 3). This indicates the presence of a fraction of pSM in the LE state whose amount is reduced with increasing proportions of pCer. Over this composition range, pCer also causes an increase of the collapse pressure, indicating nonideal mixing of pCer and pSM that leads to monolayers with increased stability. At XpCer ≈ 0.4, the compression isotherm shows LC behavior over the whole range of surface pressures, and no LE-LC or LC-LC phase transitions are observed (Fig. 3, shaded area, and Fig. 1). This result points out a particular compositional range in which all pSM in the film acquires a condensed state. At the right-hand side of the pSM-pCer phase diagram (at XpCer > 0.5), the mixtures behave similarly to pure pCer (Fig. 3). The invariance in the LC-LC and LC-collapsed phase transition pressures can be due to immiscibility between a mixed condensed phase (constituted by the mixed pSM-pCer phase of XpCer ≈ 0.4) and a more enriched pCer phase. In this respect, the packing properties of pSM molecules become hidden, being compressed enough to behave as pure pCer molecules. This interpretation is consistent with the results shown in Fig. 2, where abrupt changes in molecular packing are observed near a composition of XpCer ≈ 0.40; however, the particular surface electrostatics denotes the presence of pSM, because the variation of the dipolar properties with film compression is different in the mixture than in the pure components (see Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Surface pressure versus pCer mole fraction phase diagram for pSM-pCer monolayers. LE-LC (solid triangles), LC-LC (open triangles), and LC-to-collapsed phase (CP) (solid circles) transition pressures. Error bars represent the mean ± SE, and the lines are provided as guides to the eye only. The shaded zone indicates the range of composition in which the mixed monolayer undergoes a behavior change.

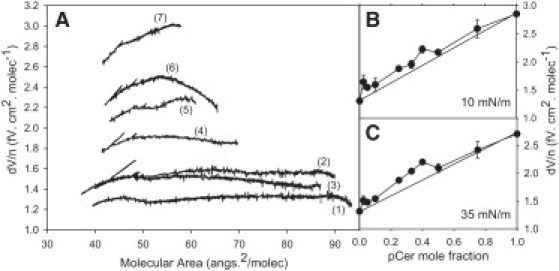

Figure 4.

Surface potential/unit molecular surface density (ΔV/n) in pSM-pCer mixed monolayers. (A) ΔV/n versus molecular area for pure pSM (1), pure pCer (7), and pSM-pCer mixtures at 5 mol % (2), 10 mol % (3), 25 mol % (4), 50 mol % (5), and 75 mol % (6) pCer. (B and C) Variation of ΔV/n of pSM-pCer mixtures with pCer mole fraction at 10 and 35 mN/m, respectively. Solid lines represent the molecular area for an ideal pSM-pCer mixture.

Changes in surface potential normalized per unit of molecular surface density (ΔV/n) are shown in Fig. 4 A for mixtures of pSM-pCer in different proportions. pCer shows relatively high values and pSM shows low values of ΔV/n over the whole range of molecular areas. The mixtures behave close to ideality at pCer mole fractions >0.5; below that proportion, they show 10–12% hyperpolarization over the whole range of surface pressures (Fig. 4, B and C). This hyperpolarization effect reveals that the existence of dipole-dipole interactions causes an increase in the resultant molecular dipole normal to the monolayer film.

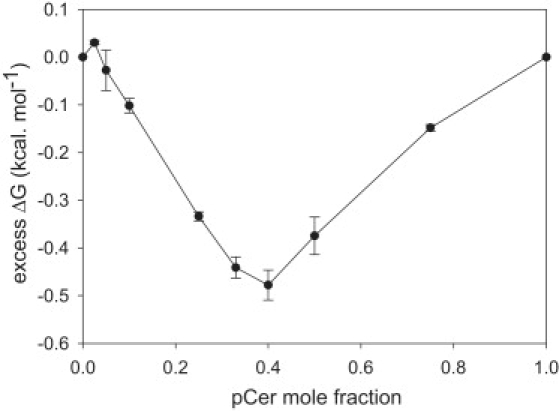

The excess compression free energy of pSM-pCer mixed monolayers reflects the influence of molecular interactions as the difference of energy required to compress a mixed monolayer from the expanded to the compressed state compared to that required to compress an ideal monolayer of the same composition in which miscibility is totally entropically driven. Fig. 5 shows that pSM-pCer mixed monolayers require less energy to pack than does an ideal mixed monolayer. This indicates that favorable interactions are established in the mixture, reaching an optimum at XpCer ≈ 0.3–0.4.

Figure 5.

Excess mixing free energy for the pSM-pCer mixture. ΔG excess was calculated as the difference in the work of compression (from the area below the compression isotherm curve) between the experimental and theoretical isotherms for ideally mixed pSM-pCer monolayers. Error bars represent the mean ± SE of duplicated experiments.

Lateral segregation of pSM and pCer in lipid monolayers

For direct observation of lipid segregation in monolayers, a small amount of the probe DiIC18 was introduced into the mixture. In the presence of two physically different phases, the probe partitions into the less ordered phase; thus, probe segregation can be used as a marker for lipid domains. Epifluorescence images of pure pSM show a homogeneous LE (bright, probe-enriched) phase over the whole range of surface pressures (Fig. 6 A shows a representative image for all surface pressures). Addition of pCer induces formation of laterally segregated domains of a LC (dark, probe-depleted) phase (Fig. 6, B–D), which for monolayers with low pCer content (5 and 10%) increases with surface pressure in the range 5–25 mN/m (Fig. 6 E). Above this pressure, the probe is unable to distinguish between the two phases and domain borders become diffuse (not shown). At XpCer ≈ 0.25, the LC phase extent becomes independent of the surface pressure, covering 81 ± 1% of the total area (Fig. 6, D and E). The extent of the LC phase clearly exceeds the area occupied by pCer; thus, the LC phase must consist of a mixture of pSM and pCer. As a first approach, we assumed that all pCer is present in the LC phase (taking the expanded phase as pure pSM), the mole fraction of pCer in the LC phase (XLCpCer) was calculated by taking into account the molecular area occupied by pCer, pSM in the LE state, and pSM in the LC state, as shown in Fig. 2 (see Materials and Methods for details). The calculated XLCpCer gives a result of 0.293 ± 0.004 for all images, where the LC phase, coexisting with the LE phase, exceeds 25%. This is not far from the thermodynamically stable composition (XpCer ≈ 0.30–0.40) at which all pSM becomes condensed by pCer (Figs. 1–3), as observed from compression isotherms analysis. For mixed monolayers containing only 5 and 10 mol % pCer, and at low surface pressures where the LE phase predominates, the assumption of pure pSM for the LE state is not valid. A small amount of pCer is present in the LE phase. This is evidenced from the isotherm analysis, since the thermodynamic parameters (collapse pressure and phase transition pressure) change with the addition of small amounts of pCer (see Fig. 3). Then, on the basis of the former calculation and the thermodynamically stable mixture described from the monolayer compression isotherms analysis, we propose that the LC phase is compositionally constant, with a minimum of XLCpCer ≈ 0.3, for all pressures and different total compositions (even when the extent of LE is large), as long as it is in coexistence with the pSM-enriched LE phase. Under these constraints, we calculate the mole fraction of pCer (XLEpCer) present in the LE phase for the different compositions (see Materials and Methods for details). pCer is partially miscible in the pSM-enriched LE phase at 5 mN/m and becomes less miscible with the increase of surface pressures, reaching an XLEpCer limit in the 4–6 mol % range (Fig. 6 F). This behavior explains the observed surface-pressure-dependent increase of dark area in the micrographs (Fig. 6 E). In summary, we can describe the pattern shown by mixed monolayers of pSM-pCer, with a pCer content of XpCer < ∼0.3, as a system showing heterogeneous phase coexistence, in the micrometer range, of two mixed phases: a pSM-enriched LE and a pCer-enriched LC, with pCer content ∼5 and ∼30 mol %, respectively. This result is consistent with a similar analysis of mixed monolayers containing mixtures of natural SM and Cer (24). In that work, it was proposed that Cer-enriched domains containing XCer ≈ 0.53 ± 0.06 are surrounded by an SM-enriched phase containing XCer ≈ 0.02. This interpretation explains the paradoxical conclusion from monolayer compression isotherm analysis: the molecular area/composition study is shown to follow Raoult's law in the XpCer range 0–0.4 (Fig. 2, B and C), indicating immiscibility (or ideal miscibility) of components; on the contrary, the phase diagram analysis shows nonideal mixing behavior for the mixed monolayers over the same compositional range. Both behaviors can be explained with the proposed model of immiscibility and phase segregation of two pSM-pCer mixtures of different composition.

Lateral segregation of pSM and pCer in lipid vesicles

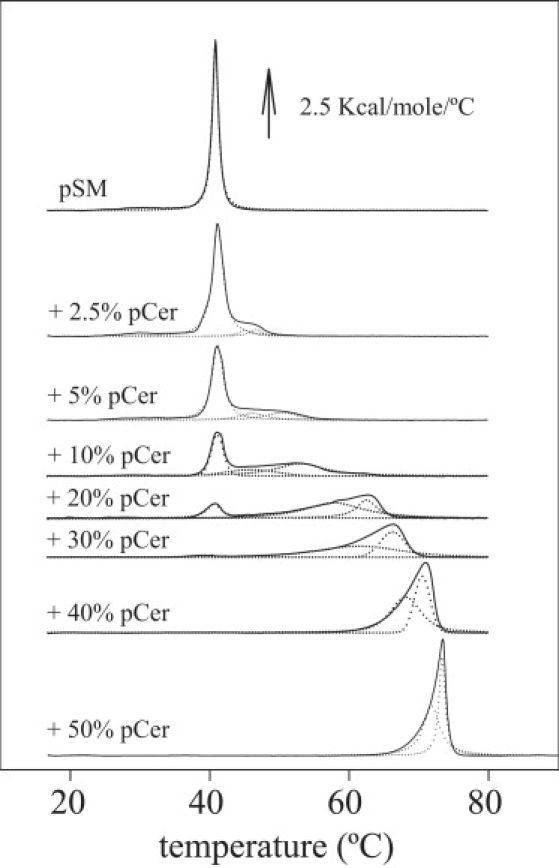

To explore the interaction and organization of both lipids in vesicles, our first approach was to use a calorimetric assay to study the effect of pCer on the pSM gel-fluid lamellar phase transition. Thermograms for the different pSM-pCer mixtures are shown in Fig. 7. Pure pSM displays a cooperative gel-fluid phase transition centered at 40.8°C. A small concentration of 2.5 mol % pCer induces the appearance of an asymmetric shoulder at higher temperatures on the pSM phase transition, reflecting the formation of one or more pCer-enriched domains in the Lβ-gel phase within the vesicles. In the concentration range XpCer = 0.025–0.3, the endotherms can be deconvoluted into three main components (Fig. 7, dotted lines), reflecting on one hand a pSM-enriched phase and on the other at least two pCer-enriched phases of different composition. Above XpCer = 0.3, the pSM lamellar phase transition is no longer detected, and a mixed pSM-pCer composition is supposed for the vesicles. The presence of pure pCer domains would not be expected, as there is no evidence of its unique calorimetrically detectable endothermic phase transition at 93.2°C in any of the mixtures assayed (not shown). The pattern observed for the high-temperature-melting, pCer-enriched domain formation is very similar to that obtained by Sot et al. (19) for the natural egg-derived lipid mixture that contained 84 mol % palmitoylated chains. The high-temperature-melting, pCer-enriched DSC endotherm is asymmetric, and it can be deconvoluted into two components, presumably with slight differences in pSM/pCer ratio (Fig. 7). In this study, as previously (19), we want to stress that in the binary mixtures, the individual DSC band components do not necessarily correspond to individual lipid phases. Rather, and particularly in the “intermediate” peak, whose maximum T shifts from ∼45°C to ∼72°C as the proportion of pCer increases, domains of different composition are likely to coexist.

Figure 7.

DSC of pSM-pCer vesicles. Representative thermograms for pSM vesicles with increasing proportions of pCer (in mol %). Dotted lines correspond to deconvoluted endotherms.

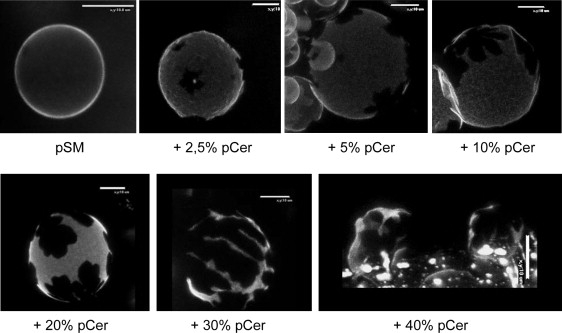

A further experimental approach involved the use of stained GUVs. Confocal microscopy of giant vesicles has evolved in recent years as a powerful technique for the study of lipid domains. Fig. 8 shows representative DiIC18-stained pSM vesicles in the presence of different pCer proportions at room temperature. Pure pSM vesicles show homogeneous distribution of the probe, indicating a unique Lβ (gel) phase through the whole vesicle. Once more, small pCer concentrations induce laterally segregated pCer-enriched domains, as expected from the calorimetric data on multilamellar vesicles. As in the case of monolayers, immiscibility between the two lipids is observed, lateral segregation reflecting the condensing effect of pCer over pSM. The domains grow in size in parallel with pCer concentration, and percolation can be observed at around XpCer = 0.30. The initially discontinuous pCer-enriched phase becomes continuous, whereas the continuous pSM-enriched phase becomes segregated. Above this concentration, the vesicles collapse, probably because of the impossibility of supporting such a condensing effect.

Figure 8.

Confocal microscopy of DiIC18-stained pSM GUVs in the presence of increasing proportions of pCer at room temperature. Bright and dark areas represent probe-enriched (pSM-enriched) and probe-depleted (pCer-enriched) phases, respectively. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Discussion

The fact that ceramide generation via sphingomyelin hydrolysis appears to be an early step in apoptosis confers a special interest on the properties of sphingomyelin-ceramide mixtures. Even though the surface behavior of ceramide and sphingomyelin in natural membranes is certainly more complex, many of the results obtained so far using simplified mixtures of the two lipids in reconstituted monolayers and bilayers have provided solid molecular bases for understanding their function (36). In this article, we have combined monolayer and bilayer approaches to study a chemically defined mixture, namely, pSM-pCer in aqueous dispersion. In both systems, pCer exerts a number of effects in a dose-dependent way up to XpCer ≈ 0.3–0.4 (Figs. 2, 3, 5, 7, and 8), with a different pattern observed above that concentration range. An interpretation of these data, proposed previously on the basis of lipid bilayer observations (19), is that pCer-rich and pCer-poor phases are immiscible and phase-segregated. In this article, further progress in describing the system is achieved through the combined use of monolayer and bilayer techniques, and the quantitative estimation of phase compositions.

In the range XpCer ≈ 0–0.4, monolayer experiments show a strong condensing effect exerted by the addition of pCer (Fig. 2). This appears to be due to incorporation of pSM into pCer-enriched liquid-condensed domains with a concomitant phase state change of the pSM molecules from LE to LC (Figs. 2 and 6). After the compositional point XpCer ≈ 0.30–0.40, only one condensed phase is observed in which the molecules are highly packed and the dipole moment increases with pCer content (Fig. 3, 4, and 6). The estimation of two coexisting phases in pSM-rich monolayers, composed of ∼5 and 30 mol % pCer, respectively, is compatible with the measurements performed on vesicle bilayers. In the limit case of 30 mol % pCer, the pSM transition is hardly detectable by DSC (Fig. 7), and the corresponding vesicles (Fig. 8) display only a binary area attributable to pSM-enriched bilayers. A pSM-rich DSC endotherm is no longer visible in mixtures containing >30 mol % pCer (Fig. 7), and GUVs containing >40 mol % pCer cannot be formed (Fig. 8), presumably because a certain proportion of pSM-rich bilayer is required for vesicle stability. Note, however, that the thermograms in Fig. 7 reveal two components in the high-temperature melting fraction, suggesting a more complex situation. We cannot confirm at this time whether they correspond to two different mixtures with very similar properties. Nevertheless, several independent observations suggest the existence of more than one pCer-enriched phase. The monolayer analysis presented would be consistent with the explanation that the LC (pCer-enriched) phase observed in monolayers at XpCer > 0.4 is in fact a mixture of two condensed phases. Supporting this explanation is the invariance of the LC-LC transition and collapse pressures, suggesting immiscibility between the stable mixture, at XpCer ≈ 0.4, and a phase enriched in pCer (Fig. 3, right-hand side). The existence of two LC phases (observed to have different compressibility moduli) in monolayers with a high content of pCer, and even in pure pCer monolayers (Figs. 1 B (inset) and 3) also suggests the coexistence (at least in a narrow range of pressure) of two LC phases each with different features. Along these lines, Schwille's group also showed evidence of the existence of more than one phase in Cer-enriched domains formed in DOPC/cholesterol/SM/Cer bilayers by AFM (37). Also, Sot et al. (19) observed domain coexistence in a large region of the egg SM/egg Cer temperature-composition diagram using a combination of calorimetric, fluorescence quenching, and temperature-dependent turbidimetric measurements.

As an alternative, curvature effects in bilayers could favor a relative enrichment in pCer in the inner monolayer because of its negative curvature (3,38), and, thus, the formation of two kinds of pCer-rich domains in curved bilayers. A discussion of the interpretation of combined physical data from monolayers and bilayers can be found in Goñi et al. (36). Direct evidence of a strong pSM-pCer interaction is shown in Fig. 5. A large favorable compression excess free energy is observed for mixed monolayers with an optimum composition in the range XpCer ≈ 0.30–0.40. The data, in agreement with previous suggestions (31,39), are in favor of a strong pSM-pCer interaction in a ratio of ∼2:1 (pSM/pCer). This thermodynamically more stable mixture coincides with the composition at which a pSM-enriched phase is no longer detectable in monolayers (Figs. 1, 3, and 6) or in bilayers (Figs. 7 and 8), and this stable mixture scarcely mixes with phases more enriched either in pSM or in pCer. This behavior suggests the existence of an optimum range for pSM/pCer interaction at ∼2:1. McConnell and Radhakrishnan (40) have suggested the existence of phospholipid/cholesterol “complexes” in which an optimum stoichiometry is necessary for the establishment of a stable (although dynamic) packing conformation.

A further aspect that deserves some comment is the difference in morphology observed for pCer-enriched domains in monolayers. Although small pCer concentrations induce segregation in branchlike structures, higher concentrations promote circular and/or peanutlike domain generation. These differences can be understood in terms of a competition between two opposing effects, namely line tension at the domain borders and perpendicular dipole-dipole repulsion between coexisting phases, according to McConnell's shape transition theory (41). In the presence of 10 mol % pCer, domain morphology shows almost circular shapes. By contrast, at 5 mol % pCer, round shapes are no longer stable and branched domains of relatively large size are observed (Fig. 6). The latter are likely above the critical area for circular-to-branched shape transition driven by dipolar repulsion within the domain. This effect was described in detail for SM-Cer mixed monolayers of natural sources by Hartel et al. (7). A recent work by Fanani et al. (25) described morphological changes of Cer-enriched domains where ceramide is generated by sphingomyelinase enzymatic activity. This promotes out-of-equilibrium, high-ceramide-containing, branched domains, whereas enzyme inactivation induces a change to circular shapes by driving the system into equilibrium. As determined in this study, the stable pCer concentration close to 30 mol % within pCer-enriched domains could reflect equilibrium conditions for ceramide in mixtures with sphingomyelin. Small deviations from this concentration would indicate nonequilibrium conditions and a possibly greater tendency toward branched structures.

As mentioned in the Introduction, ceramide generation through sphingomyelin hydrolysis has been related to increased membrane permeability effects (11,42). The observed stable composition (XpCer ≈ 0.3–0.4) might reflect the ceramide concentration necessary for membrane defects to occur in a specific location, which is in turn possibly related to ceramide-induced physiological mechanisms (see reviews by Goñi and colleagues (3,8,23)). Moreover, the higher rigidifying and stabilizing effect of pCer compared to pSM strongly supports the proposal that ceramide induces enzymatic platform formation in cellular plasma membranes (8,9).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (BFU2008-01637 to A.A. and BFU2007-62062 to F.M.G.), from Fundación Areces (06/01 to F.M.G.), and from the Basque Government (GIV06/42 to F.M.G.). J.V.B. was a predoctoral student supported by the Basque Government. Work in Córdoba was supported by Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología de la Provincial de Córdoba, SECyT-Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET) and Fondo para la Investigación Científica y Tecnológica (FONCyT-Argentina); some aspects of this investigation are inscribed within the PAE 22642 network in Nanobiosciences. B.M. and M.L.F. are Career Investigators and L.D.T. is a Doctoral Fellow of CONICET.

References

- 1.Hannun Y.A., Loomis C.R., Merrill A.H., Bell R.M. Sphingosine inhibition of protein kinase C activity and of phorbol dibutyrate binding in vitro and in human platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:12604–12609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolesnick R.N. 1,2-diacylglycerols but not phorbol esters stimulate sphingomyelin hydrolysis in GH3 pituitary cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:16759–16762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kolesnick R.N., Goñi F.M., Alonso A. Compartmentalization of ceramide signaling: physical foundations and biological effects. J. Cell. Physiol. 2000;184:285–300. doi: 10.1002/1097-4652(200009)184:3<285::AID-JCP2>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lahiri S., Futerman A.H. The metabolism and function of sphingolipids and glycosphingolipids. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2007;64:2270–2284. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7076-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maggio B. The surface behavior of glycosphingolipids in biomembranes: a new frontier of molecular ecology. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 1994;62:55–117. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holopainen J.M., Subramanian M., Kinnunen P.K. Sphingomyelinase induces lipid microdomain formation in a fluid phosphatidylcholine/sphingomyelin membrane. Biochemistry. 1998;37:17562–17570. doi: 10.1021/bi980915e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Härtel S., Fanani M.L., Maggio B. Shape transitions and lattice structuring of ceramide-enriched domains generated by sphingomyelinase in lipid monolayers. Biophys. J. 2005;88:287–304. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.048959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cremesti A.E., Goñi F.M., Kolesnick R.N. Role of sphingomyelinase and ceramide in modulating rafts: do biophysical properties determine biologic outcome? FEBS Lett. 2002;531:47–53. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03489-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grassmé H., Riethmüller J., Gulbins E. Biological aspects of ceramide-enriched membrane domains. Prog. Lipid Res. 2007;46:161–170. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Westerlund B., Slotte J.P. How the molecular features of glycosphingolipids affect domain formation in fluid membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1788:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruiz-Argüello M.B., Basañez G., Goñi F.M., Alonso A. Different effects of enzyme-generated ceramides and diacylglycerols in phospholipid membrane fusion and leakage. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:26616–26621. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.26616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siskind L.J., Colombini M. The lipids C2- and C16-ceramide form large stable channels. Implications for apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:38640–38644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000587200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Contreras F.X., Villar A.V., Alonso A., Kolesnick R.N., Goñi F.M. Sphingomyelinase activity causes transbilayer lipid translocation in model and cell membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:37169–37174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303206200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang H.W., Goldberg E.M., Zidovetzki R. Ceramide induces structural defects into phosphatidylcholine bilayers and activates phospholipase A2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996;220:834–838. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carrer D.C., Maggio B. Phase behaviour and molecular interactions in mixtures of ceramide with dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine. J. Lipid Res. 1999;40:1978–1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Veiga M.P., Arrondo J.L.R., Goñi F.M., Alonso A. Ceramides in phospholipid membranes: effects on bilayer stability and transition to nonlamellar phases. Biophys. J. 1999;76:342–350. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77201-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsueh H.W., Giles R., Kitson N., Thewalt J. The effect of ceramide on phosphatidylcholine membranes: a deuterium NMR study. Biophys. J. 2002;82:3089–3095. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75650-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sot J., Aranda F.J., Collado M.I., Goñi F.M., Alonso A. Different effects of long- and short-chain ceramides on the gel-fluid and lamellar-hexagonal transitions of phospholipids: a calorimetric, NMR, and x-ray diffraction study. Biophys. J. 2005;88:3368–3380. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.057851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sot J., Bagatolli L.A., Goñi F.M., Alonso A. Detergent-resistant, ceramide-enriched domains in sphingomyelin/ceramide bilayers. Biophys. J. 2006;90:903–914. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.067710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fanani M.L., Hartel S., Oliveira R.G., Maggio B. Bidirectional control of sphingomielinase activity and surface topography in lipid monolayers. Biophys. J. 2002;83:3416–3424. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75341-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carrer D.C., Schreier S., Patrito M., Maggio B. Effects of a short-chain ceramide on bilayer domain formation, thickness, and chain mobility: DMPC and asymmetric ceramide mixtures. Biophys. J. 2006;90:2394–2403. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.074252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goñi F.M., Alonso A. Biophysics of sphingolipids I. Membrane properties of sphingosine, ceramides and other simple sphingolipids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1758:1902–1921. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goñi F.M., Alonso A. Effects of ceramide and other simple sphingolipids on membrane lateral structure. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1788:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Tullio L., Maggio B., Fanani M.L. Sphingomyelinase acts by an area-activated mechanism on the liquid-expanded phase of sphingomyelin monolayers. J. Lipid Res. 2008;49:2347–2355. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800127-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fanani M.L., De Tullio L., Hartel S., Jara J., Maggio B. Sphingomyelinase-induced domain shape relaxation driven by out-of-equilibrium changes of composition. Biophys. J. 2008;96:67–76. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.141499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahyayauch H., Larijani B., Alonso A., Goñi F.M. Detergent solubilization of phosphatidylcholine bilayers in the fluid state: influence of the acyl chain structure. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1758:190–196. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pinto S.N., Silva L.C., de Almeida R.F., Prieto M. Membrane domain formation, interdigitation, and morphological alterations induced by the very long chain asymmetric C24:1 ceramide. Biophys. J. 2008;95:2867–2879. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.129858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bianco I.D., Maggio B. Interactions of neutral and anionic glycosphingolipids with dilauroylphosphatidilcholine and dilauroylphosphatidic acid in mixed monolayers. Colloids Surf. 1989;40:249–260. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fanani M.L., Maggio B. Mutual modulation of sphingomyelinase and phospholipase A2 activities against mixed lipid monolayers by their lipid intermediates and glycosphingolipids. Mol. Membr. Biol. 1997;14:25–29. doi: 10.3109/09687689709048166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Angelova M.I., Dimitrov D.S. Liposome electroformation. Faraday Discuss. Chem. Soc. 1986;81:303–311. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sot J., Ibarguren M., Busto J.V., Montes L.R., Goñi F.M. Cholesterol displacement by ceramide in sphingomyelin-containing liquid-ordered domains, and generation of gel regions in giant lipidic vesicles. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:3230–3236. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li X.M., Smaby J.M., Momsen M.M., Brockman H.L., Brown R.E. Sphingomyelin interfacial behaviour: the impact of changing acyl chain composition. Biophys. J. 2000;78:1921–1931. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76740-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li X.M., Momsen M.M., Brockman H.L., Brown R.E. Sterol structure and sphingomyelin acyl chain length modulate lateral packing elasticity and detergent solubility in model membranes. Biophys. J. 2003;85:3788–3801. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74794-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holopainen J.M., Brockman H.L., Brown R.E., Kinnunen P.K. Interfacial interactions of ceramide with dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine: impact of the N-acyl chain. Biophys. J. 2001;80:765–775. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76056-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kundu S., Langevin D. Fatty acid monolayer dissociation and collapse: effect of pH and cations. Colloids Surf. A. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2008;325:81–85. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goñi F.M., Alonso A., Bagatolli L.A., Brown R.E., Marsh D. Phase diagrams of lipid mixtures relevant to the study of membrane rafts. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1781:665–684. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chiantia S., Kahya N., Ries J., Schwille P. Effects of ceramide on liquid-ordered domains investigated by simultaneous AFM and FCS. Biophys. J. 2006;90:4500–4508. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.081026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Helfrich W. Elastic properties of lipid bilayers: theory and possible experiments. Z. Naturforsch. C. 1973;28:693–703. doi: 10.1515/znc-1973-11-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Megha E.L. Ceramide selectively displaces cholesterol from ordered lipid domains (rafts): implications for lipid raft structure and function. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:9997–10004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309992200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McConnell H.M., Radhakrishnan A. Condensed complexes of cholesterol and phospholipids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2003;1610:159–173. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McConnell H.M. Harmonic shape transitions in lipid monolayer domains. J. Phys. Chem. 1990;94:4728–4731. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Montes L.R., Ruiz-Argüello M.B., Goñi F.M., Alonso A. Membrane restructuring via ceramide results in enhanced solute efflux. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:11788–11794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111568200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]