Abstract

Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5) regulates the translation of amyloid precursor protein (APP) mRNA. Under resting conditions, mRNA is bound to and translationally repressed by the fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP). Upon group 1 mGluR activation, FMRP dissociates from the mRNA and translation ensues. APP levels are elevated in the dendrites of primary neuronal cultures as well as in synaptoneurosomes (SN) prepared from embryonic and juvenile fmr-1 knockout (KO) mice, respectively. In order to study the effects of APP and its proteolytic product Aβ on Fragile X syndrome (FXS) phenotypes, we created a novel mouse model (FRAXAD) that over-expresses human APPSwe/Aβ in an fmr-1 KO background. Herein, we assess (1) human APPSwe and Aβ levels as a function of age in FRAXAD mice, and (2) seizure susceptibility to pentylenetetrazol (PTZ) after mGluR5 blockade. PTZ-induced seizure severity is decreased in FRAXAD mice pre-treated with the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP. These data suggest that Aβ contributes to seizure incidence and may be an appropriate therapeutic target to lessen seizure pathology in FXS, Alzheimer's disease (AD) and Down syndrome (DS) patients.

Keywords: APP, β-amyloid, FMRP, FRAXAD, PTZ, seizure, Tg2576

Introduction

Amyloid precursor protein (APP) mRNA is translationally regulated by the fragile X mental retardation (FMRP) protein [1]. These data suggest a molecular link between Fragile Xsyndrome (FXS), a neurodevelopmental disorder, and Alzheimer's disease (AD), a neurodegenerative disease. Seizures are a prevalent phenotype in FXS, AD and Down syndrome (DS) [2–5] leading to the hypothesis that over-expression of APP/Aβ in these disorders contributes to this pathology.

FXS mice have a neomycin cassette inserted into the fmr-1 gene to block the synthesis of FMRP [6]. These mice mimic many of the pathological and behavioral phenotypes of FXS, over-express APP, Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 [1], and are highly susceptible to audiogenic-induced seizures (AGS) [7–9]. In order to study the effects of APP/Aβ expression on FXS phenotypes, we created FRAXAD mice, a cross of fmr-1 KO mice and Tg2576, an AD mouse model that over-expresses human APPSwe. FRAXAD mice (postnatal day 14–16) have 23% more brain Aβ1–40 than Tg2576 and display significantly increased early mortality compared to Tg2576, WT and fmr-1 KO mice, consistent with a developmental defect [10]. Both Tg2576 and FRAXAD have a significantly lower threshold to pentylenetetrazol (PTZ)-induced seizures compared to non-transgenic littermates, which suggests that APP/Aβ contribute to juvenile mortality by decreasing seizure threshold [10].

How APP or its proteolytic products contribute to seizure propensity remains unknown. Others and we have shown that mGluR5 inhibitors including MPEP can rapidly attenuate audiogenic seizures (AGS) in fmr-1 KO mice [11]. mGluR5 blockade also prevents DHPG-mediated up-regulation of APP synthesis in synaptoneurosomes (SN) [1]. Based on these data, we asked if mGluR5 blockade would reduce seizure susceptibility in response to PTZ. Consequently, we assessed APP and Aβ levels during development in Tg2576 and FRAXAD mice and the ability of mGluR5 blockade to attenuate PTZ-induced seizures in these strains. PTZ-induced seizure severity is decreased in FRAXAD mice pre-treated with the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP. Thus, mGluR5 blockade reduces both APP/Aβ production as well as signaling.

Methods

Animal Husbandry

WT, fmr-1-/-, Tg2576 and FRAXAD mice were generated, bred and housed as previously described [10]. All strains were in the C57BL/6 background (backcross n = 5 or greater). APPSwe and fmr-1 KO genotypes were determined by PCR analysis of DNA extracted from tail biopsies. Adequate measures were taken to minimize pain or discomfort to the mice, and all husbandry, seizure and euthanasia procedures were performed in accordance with NIH guidelines and an approved University of Wisconsin Madison animal care protocol administered through the Research Animal Resources Center.

Molecular Analyses (westerns, ELISAs and secretase assays)

For the detection of mouse APP/Aβ, brain regions (hippocampus, cortex and cerebellum) from WT and fmr-1 KO brains of 3.5 month-old mice were homogenized in 0.5 mL protein extraction buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 7.6], 2 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.25% NP-40, and 1X protease inhibitor cocktail) and clarified at 12,000 rpm, 10 min, 4°C. Protein concentrations were determined by the Pierce BCA assay (http://www.piercenet.com). Lysates were analyzed by western blotting and ELISA. Western membranes were hybridized with anti-mouse APP antibody (Chemicon catalog#mAB348, dilution, 5u.g/mL) and anti-mouse β-actin antibody (dilution, 1:10,000) followed by hybridization with anti-mouse HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (dilution, 1:2,000). Proteins were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence on a STORM 860 phosphorimager. Sandwich ELISAs with the Signet Aβ1–40/9131 and Signet Aβ1–42/9134 capture antibodies and the rodent Aβ/9154 reporter antibody to detect mouse Aβ were performed as previously described [12].

For the detection of human APP/Aβ, brain hemispheres were homogenized in 8M GnHCl buffer (8M GnHCl, 50 mM Tris pH 7.5), mixed at room temperature for 4 hr, aliquoted and frozen at -80°C. Protein concentrations were determined by the Pierce BCA Assay (http://www. piercenet.com). Lysates were diluted at least 80–100-fold to obtain GnHCl concentrations below 0.1 M and clarified at 16,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C. Samples were further diluted as per the figure legends to obtain concentrations in the linear range of the standard curve. BioSource ELISA assays were employed to detect APP/APPα (catalog #KHB0051), Aβ1–40 (catalog #KHB3482) and Aβ1–42 (catalog #KHB3442) (http://www.invitrogen.com).

α- and β-secretase activities were assessed with R & D System kits #FP001 and #FP002 (http://www.rndsystems.com). Briefly, brain hemispheres were homogenized in 5 mL kit cell extraction buffer, set on ice for 30 min with occasional mixing and spun at 10,000 rpm for 1min at 4°C. The protein concentration of the cleared lysates was determined by the Pierce BCA assay (http://www.piercenet.com). Lysates (2 mg/mL stocks) were diluted 10-fold (α-secretase assay) or 50-fold (β-secretase assay). Reactions contained 50 U.L diluted lysate, 50 ul 2X reaction buffer and 5 ul substrate and were incubated in the dark at 37°C for 1 hr (BACE) or 2 hr (α-secretase) per the manufacturer's directions. Fluorescence was measured on a SpectraMax Gemini Fluorescence plate reader with Softmax Pro software from Molecular Devices (http://www.moleculardevices.com).

PTZ-Induced SeizureTestingand Data Analyses

MPEP was a kind gift from FRAXA Research Foundation (Newburyport, MA) and was dissolved at 1 mg/mL in DPBS before I.P. injection at 30 mg/kg body weight 30 min prior to PTZ treatment. PTZ(catalog#P6500) was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (http://www.sigmaaldrich.com), dissolved at2 mg/mLin DPBSand administered by I.P. injection (50 mg/kg body weight). Seizure testing was conducted and scored as previously described [10].

Results

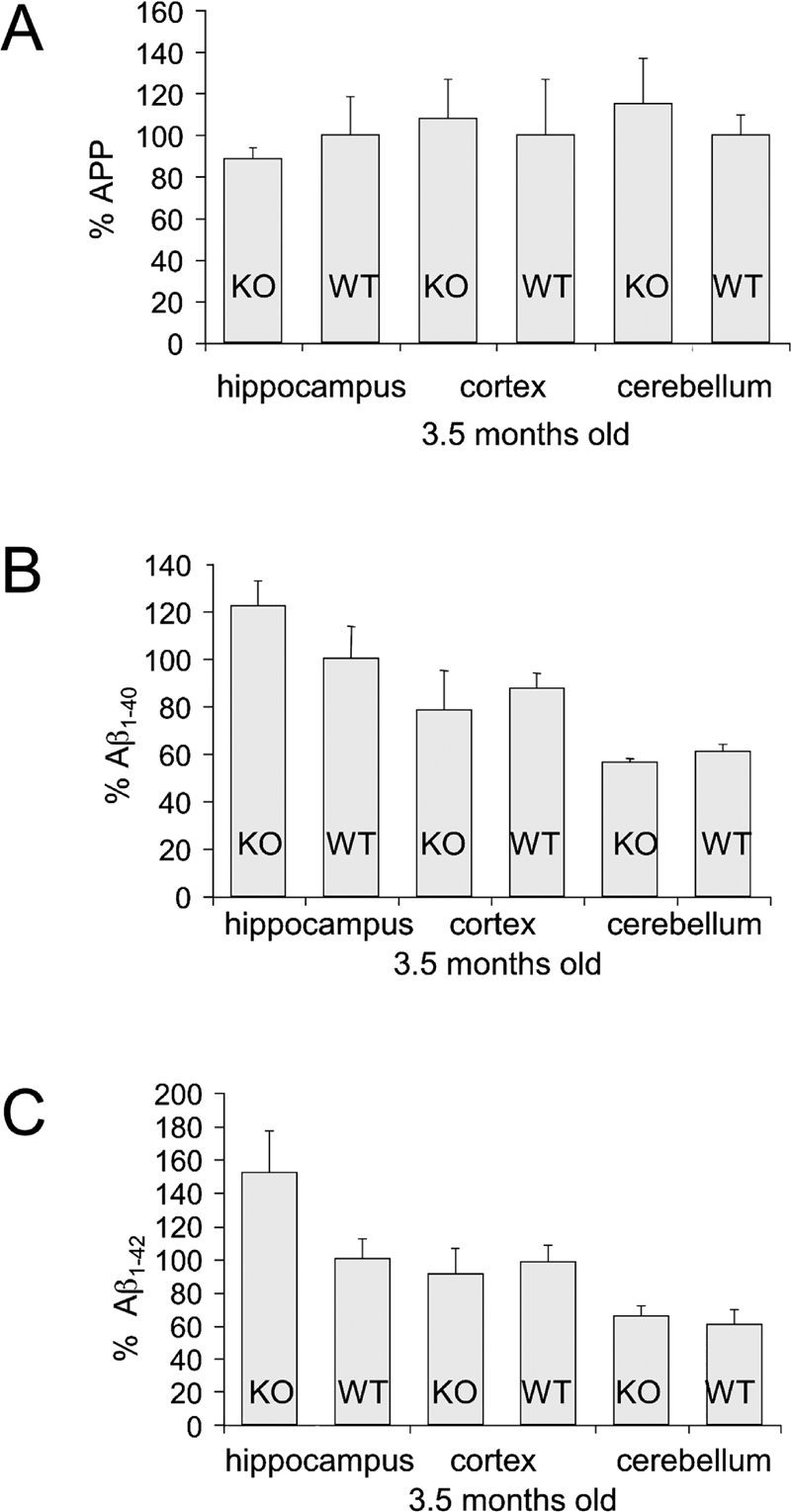

We assessed APP and Aβ levels in WT, fmr-1-/-, Tg2576 and FRAXAD mice as a function of age. There was no difference in brain APP levels in WT versus fmr-1-/- (3.5 months old) as assessed by western blotting of hippocampal, cortical and cerebellar lysates (Figure 1A). However, we have previously demonstrated increased APP in fmr-1 KOsynaptoneurosomes prepared from young mice (P14–17) as well as increased dendritic APP in fmr-1 KO primary neuronal cells [1].

Figure 1.

WT and fmr-1 KO mice (3.5 months old) have equivalent levels of brain APP and Aβ. (A) APP levels in lysates from hippocampus, cortex and cerebellum brain regions of WT and fmr-1 KO mice (25 μg per lane) were assessed by western blot analyses. Phosphorimager units for APP were normalized to β-Actin levels. All WT samples were set to 100%. There was no statistical difference between WT (n = 3) and fmr-1 KO mice (n = 3 mice). (B) Aβ1–40 and (C) Aβ1–42 levels in hippocampus, cortex and cerebellum brain regions of WT (n = 3) and fmr-1 KO (n = 3) mice were assessed by ELISA and presented as a percentage compared to levels in WT hippocampus. The 1.5X increase in Aβ1–42 levels in fmr-1 KO brain was not statistically significant (p = 0.14).

Thus, APP expression is selectively elevated in embryonic and juvenile fmr-1 KO mice compared to WT. FMRP levels decrease with aging in WT mice [13], suggesting APP translation and processing might gradually increase over time. Indeed, one-year old fmr-1 KO mice have elevated Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 in whole brain lysates [1]. There was a trend towards similar data in hippocampal lysates from 3.5 month-old mice (Figure 1B, C), but the differences had not reached statistical significance at this age.

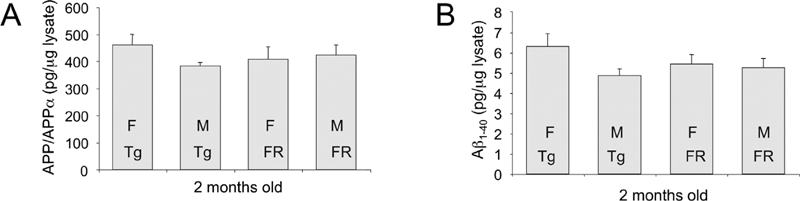

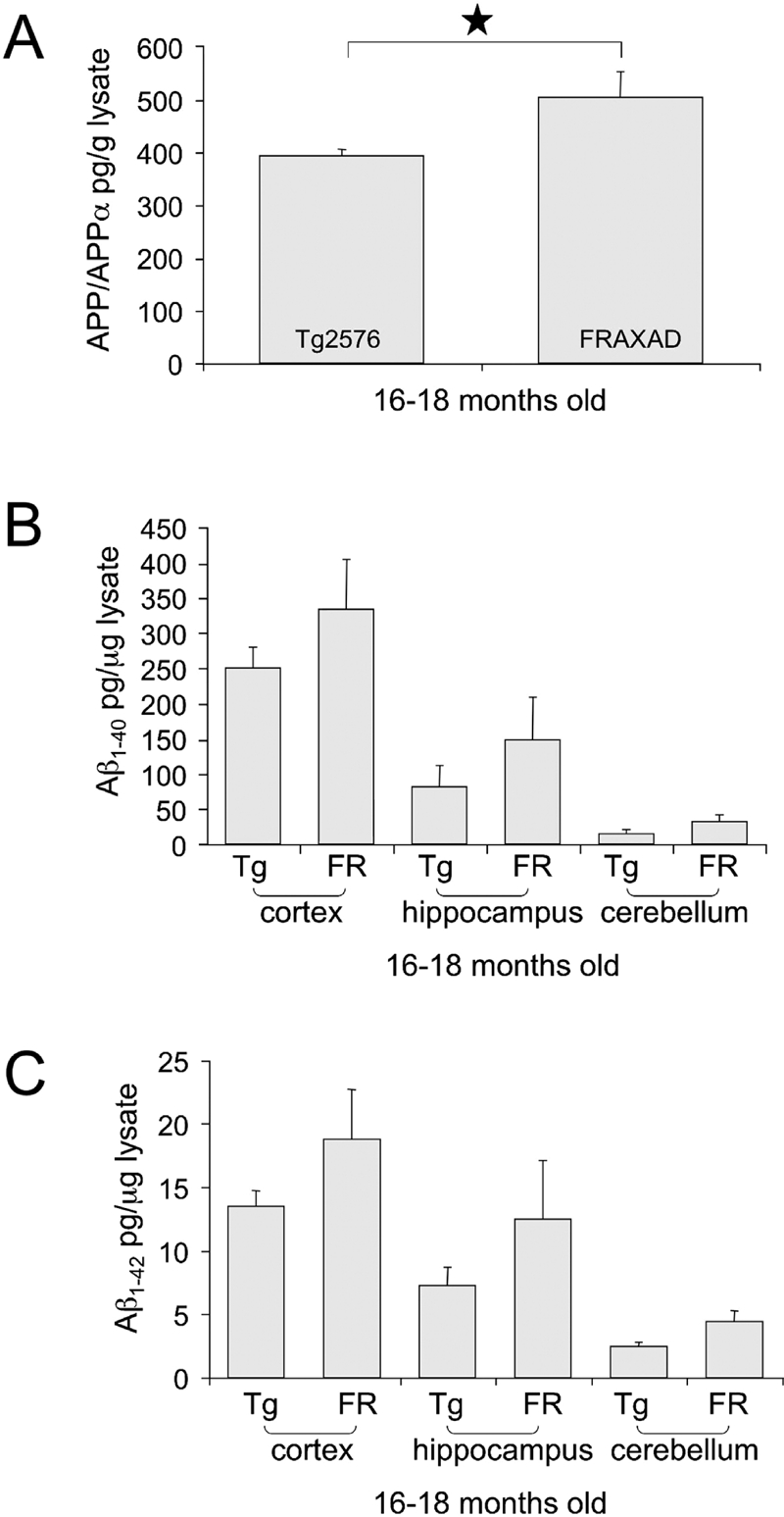

Next, we assessed APP and Aβ levels in Tg2576 and FRAXAD mice from neonatal life to adulthood. FRAXAD mice produce significantly more Aβ1–40 by 2 weeks of age than Tg2576 as assessed by ELISA of whole brain lysates [10]. Hence, we assessed APP and Aβ levels in Tg2576 and FRAXAD mice at later stages of development. We hypothesized that the absence of FMRP in the FRAXAD mice would result in increased synthesis of APP and hence generation of Aβ, which would accumulate with aging. We did not observe significant differences in APP or Aβ1–40 between Tg2576 and FRAXAD by ELISA at 2 months of age (Figure 2). Aβ1–42 was not detectable above background at this age. At 16–18 months of age, there was a statistically significant 28% increase in APP/APPα in whole brain lysates of FRAXAD versus Tg2576 (Figure 3A). There were trends for increased Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 in hippocampus, cortex and cerebellum (Figures 3B, C), which were not statistically significant. There were only n = 3–4 animals per cohort due to a 40% mortality rate by 60 days of age in both Tg2576and FRAXAD [10]. The mice that survived 16–18 months were the healthiest and thus might be expected to have lower than typical levels of human APPSwe and Aβ.

Figure 2.

APP and Aβ Levels in Young Adult Tg2576 and FRAXAD Mice. GnHCl-soluble lysates were prepared from brain hemispheres harvested from 2-month old mice and diluted 1:100 to reduce the GnHCl concentration to below 0.1 M. Lysates were further diluted 1:5 for APP/APPα analyses. (A) APP/APPα and (B) Aβ1–40 ELISAs were performed as described in the Methods Section and plotted as pg/μg lysate. There were no statistically significant differences between Tg2576 (Tg) [females (F): n = 7, males (M): n = 8] and FRAXAD (FR) [F: n = 7, M: n = 7] mice.

Figure 3.

FRAXAD Mice (16–18 months) Exhibit Elevated Brain APP/APPα Compared to Age-Matched Tg2576. GnHCl-soluble lysates were prepared from 16–18-month old Tg2576 (n = 4) and FRAXAD (n = 3) mice and diluted 1:800 (APP/APPα), 1:25,000 (Aβ1–40) or 1:75,000 (Aβ1–42) for ELISA analyses of (A) APP/APPα in brain hemispheres and (B) Aβ1–40 and (C) Aβ1–42 in hippocampus, cortex and cerebellum brain regions. There was a statistically significant 28% increase in APP/APPα levels in FRAXAD brain (p<0.05). There was a trend for increased Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 in cortex, hippocampus and cerebellum but the differences were not statistically significant between Tg2576 and FRAXAD.

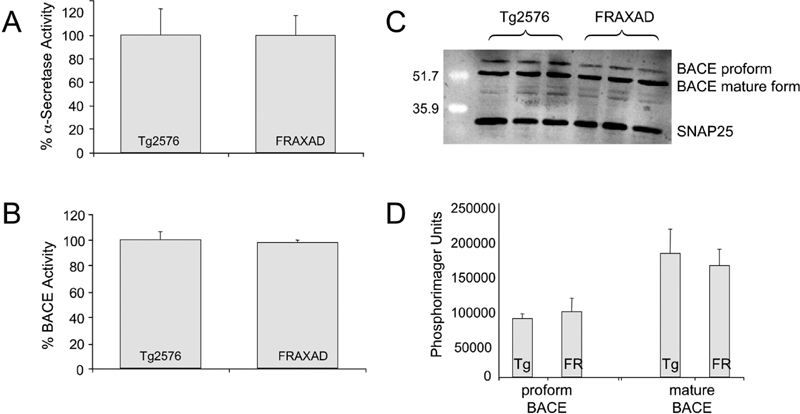

To test if the APP processing machinery was equally active in Tg2576 and FRAXAD, we assessed α and β-secretase activity in mouse brain lysates. APP is cleaved by two proteases to produce Aβ. The amino-terminal end of Aβ is produced by APP cleavage between Met671 and Asp672 by β-secretase (BACE; aspartyl protease 2) and the carboxy-terminus by cleavage between Val711 and Val712 (Aβ1–40) or between Ile713 and Ala714 (Aβ1–42) by γ-secretase [APP770 codon numbering system]. The Swedish familial mutation (Asn671/Leu672) of APP increases the propensity for cleavage by β-secretase. Cleavage of APP by α-secretase within the Aβ region precludes formation of Aβ. There were equivalent β- and α-secretase activities in lysates prepared from Tg2576 and FRAXAD brain lysates (Figure 4A, B) and equivalent levels of both the proform and mature form of BACE (Figure 4C, D). The anti-BACE antibody reacts with the carboxy-terminus of BACE and the calculated molecular weight of the protein based on amino acid content is 70 kDa. However, the observed molecular weight is in the range of 60–75 kDa due to glycosylation of mature and proform proteins. Equivalent secretase activity and levels of BACE in Tg2576 and FRAXAD indicate that the Aβ processing machinery was intact in the FRAXAD mice.

Figure 4.

Tg2576 and FRAXAD Mice Have Equivalent α- and β-Secretase Activity. The enzymatic activities of α-secretase (A) and β-secretase (B) were quantitated by R&D Systems fluorometric assays of whole brain lysates prepared from Tg2576 (n = 3) and FRAXAD (n = 3) mice (9 months old). The proform and mature forms of BACE were assessed by western blot analyses (C) and quantitated with ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics, Inc.) (D). Lysates (100 μg per lane) prepared in cell extraction buffer were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to 0.45 u,m nitrocellulose. Blocked membranes were hybridized with anti-BACE (dilution, 1 u,g/mL, Zymed catalog #34–4900) and anti-SNAP25 (dilution, 1:2000, Abcam catalog #ab5666) followed by anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated secondary antibody and visualization with ECL+, n = 3 each.

The mGluR theory of FXS suggests that mGluR5 antagonists are able to place a brake on protein translation and thus revert fmr-1-/- phenotypes [14]. MPEP is a specific and potent noncompeti-tive antagonist of mGluR5 that is capable of crossingthe blood brain barrier [15–16]. Hence, we tested the ability of MPEP to reduce PTZ-induced seizures in WT, fmr-1-/-, Tg2576 and FRAXAD mice (Tables 1 & 2). PTZ is a potent, competitive antagonist at inhibitory GABAA neurons [17] and fmr-1 KO mice have a normal sensitivity to PTZ [7] whereas Tg2576 and FRAXAD are highly sensitive [10]. MPEP (30 mg/kg body weight via I.P. injection 30 min prior to PTZ) minimally reduced seizure end-point scores in WT and fmr-1 mice from 1.89, 2.42, 2.55 and 2.85 to 1.78, 2.20, 2.33 and 2.13 for WT females and males and fmr-1-/- females and males, respectively (Table 1). These reductions were not statistically significant. However, MPEP did exhibit anti-convulsant activity by reducingthe number of mice exhibiting grade 3 seizures. WT male mice reach a grade 3 seizure [fully developed minimal seizure with clonus of the head muscles and forelimbs] at a rate of 50% (n = 6/12) in response to 50 mg/kg PTZ [10], but only 20% achieve a grade 3 seizure after MPEP treatment (n = 2/10) (Table 2) (statistically significant, Chi-squaretest, p < 0.05). There was a reduction from 11% (n = 1/9) to 0% (n = 0/9), 38% (n = 5/13) to 25% (n = 2/8), and 40% (n = 8/20) to 33% (n = 2/6) in WTfemales, fmr-1 KO males and fmr-1 KO females, respectively. Thus, MPEP was more effective in reducing the rate of grade 3 seizures in WT than in fmr-1 KO mice.

Table 1.

Seizure Endpoint ± MPEP

| n | Ave Age (days) | Avg Weight (g) | MPEP Seizure End-Point | n | untreated* Seizure End-Point | Difference | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT female | 9 | 58.6 ± 0.84 | 21.6 ± 0.66 | 1.78 ± 0.15 | 9 | 1.89 ± 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.65 |

| WT male | 10 | 58.1 ±0.78 | 28.6 ± 0.63 | 2.20 ± 0.25 | 12 | 2.42 ± 0.31 | 0.22 | 0.59 |

| KO female | 6 | 57.9 ± 0.95 | 20.8 ± 0.59 | 2.33 ± 0.42 | 20 | 2.55 ±0.22 | 0.22 | 0.63 |

| KO male | 8 | 57.9 ±0.74 | 27.0 ± 0.79 | 2.13 ± 0.29 | 13 | 2.85 ± 0.27 | 0.72 | 0.11 |

| Tg2576 female | 4 | 58.0 ± 1.1 | 20.1 ± 0.83 | 4.25 ±0.75 | 6 | 4.67 ±0.33 | 0.42 | 0.57 |

| Tg2576 male | 8 | 56.8 ±0.90 | 26.3 ± 0.96 | 4.63 ±0.26 | 7 | 4.57 ± 0.30 | 20.06 | 0.89 |

| FRAXAD female | 5 | 58.2 ± 1.2 | 20.6 ±0.73 | 4.4 ± 0.24 | 7 | 4.86 ± 0.14 | 0.46 | 0.12 |

| FRAXAD male | 5 | 58.0 ± 0.95 | 28.4 ± 0.85 | 4.0 ±0.63 | 12 | 4.08 ± 0.31 | 0.08 | 0.89 |

Please refer to the reference [10].

Table 2.

Latency to Seizure with MPEP

| Mouse | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 | Recovery Time (min) | Time of Death (sec) | % Mice Dead |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT Female | 168 ± 25 | 842 ± 210 | NA | NA | NA | 39 ± 4.04 | NA | 0 |

| n = 3 | n = 7 | n = 0 | n = 0 | n = 0 | n = 9 | n = 0 | ||

| WTMale | 140 ± 27 | 801±151 | 522 ± 56 | 465 | NA | 39 ± 2.54 | NA | 0 |

| n = 10 | n = 9 | n = 2 | n = 1 | n = 0 | n = 10 | n = 0 | ||

| KO Female | 90 ± 10 | 290 ± 68 | 387 ± 75 | 462 | NA | 43 ± 3.48 | NA | 0* |

| n = 6 | n = 5 | n = 2 | n = 1 | n = 0 | n = 6 | n = 0 | ||

| KO Male | 146 ± 13 | 393 ± 92 | 325 ± 80 | 244 | NA | 31 ± 3.47 | NA | 0 |

| n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 2 | n = 1 | n = 0 | n = 8 | n = 0 | ||

| Tg2576 Female | 149 ± 33 | 198 ± 16 | 368 ± 44 | 595 ±182 | 792 ± 179 | 60 | 1017 ± 5 | 50** |

| n = 2 | n = 4 | n = 3 | n = 3 | n = 3 | n = 1 | n = 2 | ||

| Tg2576 Male | 121 ± 19 | 216 ± 41 | 344 ±101 | 370 ± 114 | 576 ± 191 | 39 ± 11.00 | 725 ±161 | 75 |

| n = 3 | n = 8 | n = 8 | n = 7 | n = 6 | n = 2 | n = 6 | ||

| FRAXAD Female | 155 ±3 | 207 ± 25 | 322 ± 57 | 328 ± 55 | 223 ± 39 | 46 ± 5.05 | 267 ± 46 | 40 |

| n = 2 | n = 5 | n = 5 | n = 5 | n = 2 | n = 3 | n = 2 | ||

| FRAXAD Male | ND | 261 ±172 | 253 ± 33 | 220 ± 57 | 232 ± 56 | 52 ±0 | 340 ±139 | 60 |

| n = 5 | n = 3 | n = 3 | n = 3 | n = 3 | n = 2 | n = 3 |

2 Fmr-1 KO female mice died from MPEP alone (no PTZ injection) and were not included.

1 Tg2576 female mouse died from MPEP alone (no PTZ injection) and was not included. Of the 5 mice in the Tg2576 female group, 1 mouse had a stage 5 seizure and recovered within 1 hr, 1 mouse had a stage 2 seziure and did not recover within 1 hr, 2 mice died and 1 mouse died from MPEP alone.

Tg2576 and FRAXAD mice have average seizure scores greater than 4 on a 5-point scale compared to 2.42 ± 0.31 for WT male C57BL/6 mice in response to PTZ [10]. Tg2576 mice exhibited 83 and 100% rates of grade 3 seizures in response to PTZ as well as 83 and 71% death rates for females and males, respectively [10]. FRAXAD mice exhibited 100 and 75% rates of grade 3 seizures in response to PTZ as well as 86 and 42% death rates for females and males, respectively [10]. MPEP reduced the death rate from 83% to 50% in Tg2576 females and from 86% to 40% in FRAXAD females, but there was no reduction in the death rate for Tg2576 or FRAXAD male mice (Table 2). Of note, two fmr-1 KO and one Tg2576 female died from the MPEP injection alone and were not included in the analyses. While the average seizure endpoint for the Tg2576 and FRAXAD mice was 4.0 or greater±MPEP, there were other measurable differences in seizure sensitivity. For example, with the Tg2576 males (n=8), three of the mice underwent two rounds of grade 3 seizures before pro-gressingto grade 4 and then two rounds of grade 4 seizures before progressing to grade 5. One of these mice underwent two rounds of grade 5 seizures before dying. [Grade 5 is typically scored on the presence of hyperactive bouncing, tonic-clonic seizures and respiratory arrest, but for this analysis, the first round of grade 5 seizures includes only the hyperactive bouncing and tonic-clonic seizures.] An additional mouse in the cohort underwent one grade 3 seizure followed by two rounds of grade 4 seizures before progressing to two rounds of grade 5 seizures and death. Multiple rounds of seizure before progressing to the next seizure stage were not observed in the absence of MPEP. Of the four remaining mice in the Tg2576 male cohort, two mice had an increased latency time to grade 3 seizure after MPEP, 743 and 860 sec, versus 337.3+62 sec for PTZ alone [10]. The other two mice (25% of cohort) were indistinguishable from non-MPEP-treated Tg2576 males. This data suggests that MPEP partially attenuates PTZ-induced seizures by delaying progression to more severe seizure stages, but that blockade of mGluR5 is not enough to prevent seizures.

In the case of the FRAXAD mice, we did not observe multiple rounds of seizures in any of the animals; however, MPEP reduced the odds of a FRAXAD mouse progressing to higher-grade seizures. An odds ratio [18] of seizure severity was calculated by dividing the number of mice displaying higher-grade (4 + 5) seizures by the number having the lower grade seizure (1 + 2 + 3) within each gender/genotype. For example, the odds that a Tg2576 mouse would exhibit a higher grade seizure score was (10 +1)/(0 + 0 + 2), which indicates that this genotype was 5.5 times more likely to exhibit a seizure scored at 4 or 5 than a lower grade seizure. The odds for a WT or fmr-1 KO mouse to exhibit a grade 4 seizure were less than 0.2. The number of mice in each gender/genotype cohort as a function of seizure end-point is displayed in Table 3. An odds ratio for the probability of each strain (genders combined) undergoing high-grade (grades 4 & 5) seizures versus lower grade (grades 1, 2 and 3) is shown in Table 4. The odds ratio of a FRAXAD mouse undergoing a grade 4/5 seizure in response to PTZ drops from 8.5 to 4 after MPEP treatment. These data suggest that mGluR5 antagonists can reduce seizure severity in transgenic mice over expressing human Aβ.

Table 3.

PTZ-Induced Seizure Endpoint Distribution

| MPEP | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | no* | no* | no* | no* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gender | male | female | male | female | male | female | male | female | male | female | male | female |

| strain | WT | WT | fmr-1 KO | fmr-1 KO | Tg2576 | Tg2576 | FRAXAD | FRAXAD | Tg2576 | Tg2576 | FRAXAD | FRAXAD |

| n | 10 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 12 | 7 |

| grade 1 endpt | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| grade 2 endpt | 7 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| grade 3 endpt | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| grade 4 endpt | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 1 |

| grade 5 endpt | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| multiple grade 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| multiple grade 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| multiple grade 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2** | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Please refer to reference [10].

Grade 5 seizures involve hyperactive bouncing followed by tonic-clonic seizures and death. These mice were scored as multiple grade 5 seizures due to two rounds of hyperactive bouncing and tonic-clonic seizures. The mice recovered from the first round and later entered a second round resulting in death.

Table 4.

Odds Ratio for Tonic Seizures and Death

| MPEP | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | no |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| strain* | WT | fmr-1 KO | Tg2576 | FRAXAD | Tg2576 | FRAXAD |

| n | 19 | 14 | 12 | 10 | 13 | 19 |

| grade 1 endpt | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| grade 2 endpt | 14 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| grade 3 endpt | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| grade 4 endpt | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 6 |

| grade 5 endpt | 0 | 0 | 9 | 5 | 10 | 11 |

| Odds Ratio** | 0.06 | 0.17 | 5 | 4 | 5.5 | 8.5 |

genders combined.

odds that specified strain would exhibit grade 4 & 5 seizures.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) binds to and represses the translation of APP mRNA [1]. FMRP is a multi-functional mRNA binding protein that is ubiquitously expressed throughout the body with significantly higher levels in young animals [19]. FMRP is regulated in the neonatal brain where it peaks at the end of the first postnatal week and declines thereafter [20]. Fmr-1 mRNA and protein are down regulated in mouse brain as a function of age with a 50% reduction between young (6 weeks) and middle-age (60 weeks) mice [13]. APP is also developmentally regulated with expression increasing during neuronal differentiation, maximal during synaptogenesis, and subsequent decline when mature connections are completed [21–24].

APP plays a critical physiological role in synapse formation and maintenance. It promotes synapse differentiation at the neuromuscular junction in Drosophila [25] and increases the number of presynaptic terminals in transgenic mice [26]. siRNA targeted against APP decreases presynaptic APP/APLP2 levels and reduces syn-aptic activity in the rat superior colliculus [27]. APP/APLP2 double knockout mice exhibit defective NMJ, excessive nerve terminal sprouting and defective synaptic transmission [28]. Administration of anti-APP antibodies prevents memory formation in day-old chicks [29] and in rats [30]. Thus, misregulated expression and processing of APP during development likely play important roles in learning, memory and seizure induction/propagation.

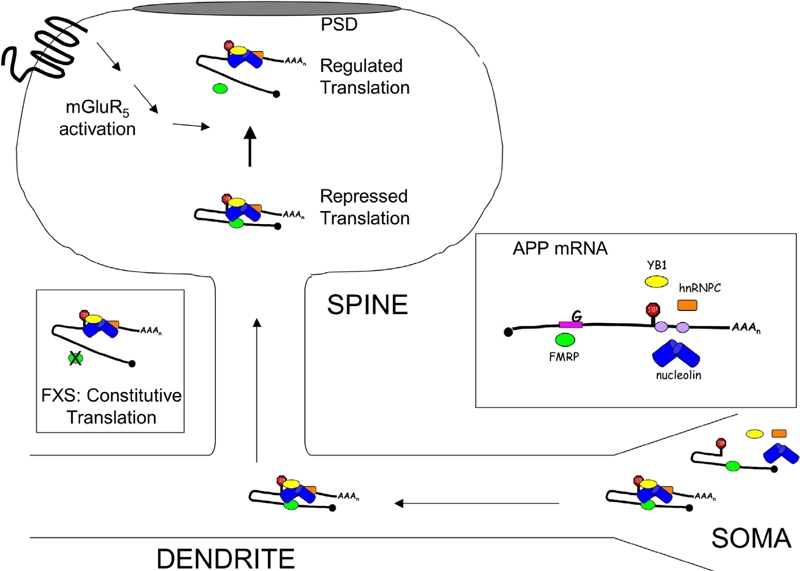

APP levels are elevated in the dendrites of embryonic neurons (E18, cultured 11 days), SN (juvenile mice P14–17) and aged fmr-1 KO brain (16–18 months old). Tg2576 over-express human APP and Aβ in a WT C57BL/6 background hence they possess an intact FMRP/mGluR5 signaling pathway whereas FRAXAD are lackingthe FMRP translational brake. Thus, we expected to observe greatly exacerbated human APP and Aβ expression in the FRAXAD mice. Surprisingly, we only observed a 28% increase in APP/APP levels in aged (16–18 months old) FRAXAD mice. We did not observe statistically significant differences in APP/APPα or Aβ1–40 levels between Tg2576 and FRAXAD at 2 months of age or in Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 at 16–18 months of age. We had previously observed a 23% increase in Aβ1–40 in brain lysates, but not SN, prepared from 14–16 day-old FRAXAD mice compared to Tg2576 [10]. In addition, brain lysates from fmr-1 KO mice showed 2.8-fold more Aβ1–40 compared to WT [1]. These data suggest differential regulation of murine versus human APP mRNA in these transgenic mice. The APPSwe cDNA expressed in Tg2576 lacks the 3'-UTR [31]. We have shown that FMRP binds to the 3'-UTR of APP mRNAsuggesting that this fragment is required for appropriate translational regulation. In addition, the 3'-UTR may be required for dendritic targeting as shown for many other mRNAs [32–35]. Indeed, immunofluorescence analyses of cultured Tg2576 neurons reveals that APPSwe is predominantly in the soma rather than the dendrites (manuscript in preparation, Westmark et al.). Both of these events would diminish the effects of FMRP KO. We present a model for APP mRNA regulation in dendrites in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Model of FMRP-Mediated Regulation of APP Translation. APP mRNA is a synaptic target for regulation by FMRP. Through UV crosslinking CLIP assays, we've shown that FMRP binds directly to the coding region of APP mRNA at a guanine-rich region. FMRP also protects a 29-base cis-element in the 3'-UTR from ribonuclease digestion of anti-FMRP immunoprecipitates [1]. RNA binding proteins such as nucleolin, hnRNP C and YB1 bind to cis-elements in the 3'-UTR [43–45]. Nucleolin and YB1 are protein binding factors of FMRP [46–47], which suggests that that protein/protein interactions bring multiple cis-elements in APP mRNA in close proximity to regulate translation (Repressed Translation State). Stimulation of cortical SN with DHPG, a group 1 mGluR agonist, releases FMRP from APP mRNA while increasing APP translation (Regulated Translation State). In the absence of FMRP (fmr-1 KO SN and primary neuronal cells), basal APP levels are increased and nonresponsive to mGluR5 signaling (FXS: Constitutive Translation State). mRNA/protein interactions are likewise important for the movement of APP mRNA from the soma to the dendrites as human APPSwe, which lacks the 3'-UTR, is localized in the soma.

Tg2576 and FRAXAD both over-express human APPSwe and Aβ and exhibit drastically reduced seizure thresholds to chemically induced seizures. The mGluR5 inhibitor MPEP rescues prepulse inhibition of the startle response and dendritic spine protrusion morphology in cultured neurons [36], courtship behavior and mushroom body defects in dfmr1 KO flies [37] and seizures induced by intracerebroventricular administration of CHPG or sound [11,38]. MPEP reduces the duration of synchronized charges in mouse hippocampal slices induced by the GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline [39], the induction of burst prolongation of epileptiform bursts [40], seizures in rats induced by pilo-carpine [41], and low dose PTZ-induced seizures in mice [42]. MPEP did not prevent PTZ-induced seizures in Tg2576 or FRAXAD mice or significantly lower average seizure endpoints, however, MPEP did: (1) lower the death rateinTg2576 and FRAXAD females, (2) produce multiple rounds of grade 3–5 seizures in Tg2576, and (3) decrease the odds ratio of a FRAXAD mouse undergoing a grade 4/5 seizure. Our data suggests that the mGluR5 signaling pathway is involved in seizure initiation/propagation.

Acknowledgments

We thank FRAXA Research Foundation for the kind gift of MPEP and the University of Wisconsin Paul P. Carbone Comprehensive Cancer Center (UWCCC) Analytical Instrumentation Laboratory for use of their SpectraMax Gemini Fluorescence plate reader. We acknowledge the expert technical assistance provided by the University of Wisconsin-Madison animal care staffs at the Waisman Center and Rennebohm Pharmacy. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01AG10675 and DA026067 (J.S.M.) and P30 HD03352 (Waisman Center), FRAXA Research Foundation (C.J.W.), State of WI grant money (Wisconsin Comprehensive Memory Program) and a private donationby Bill and Doris Willis (Waisman Center).

References

- 1.Westmark CJ, Malter JS. FMRP mediates mGluR5-dependent translation of amyloid precursor protein. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e52. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hagerman RJ, Hagerman PJ. Physical and Behavioral Phenotype. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Velez L, Selwa LM. Seizure disorders in the elderly. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:325–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Risse SC, Lampe TH, Bird TD, Nochlin D, Sumi SM, Keenan T, Cubberley L, Peskind E, Raskind MA. Myoclonus, seizures, and paratonia in alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1990;4:217–225. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199040400-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Menendez M. Down syndrome, alzheimer's disease and seizures. Brain Dev. 2005;27:246–252. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fmr1 knockout mice: A model to study fragile X mental retardation. the dutch-belgian fragile X consortium. Cell. 1994;78:23–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen L, Toth M. Fragile X mice develop sensory hyperreactivity to auditory stimuli. Neuroscience. 2001;103:1043–1050. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Musumeci SA, Bosco P, Calabrese G, Bakker C, De Sarro GB, Elia M, Ferri R, Oostra BA. Audio-genic seizures susceptibility in transgenic mice with fragile X syndrome. Epilepsia. 2000;41:19–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb01499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan QJ, Asafo-Adjei PK, Arnold HM, Brown RE, Bauchwitz RP. A phenotypic and molecular characterization of the fmr1-tm1Cgr fragile X mouse. Genes Brain Behav. 2004;3:337–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2004.00087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Westmark CJ, Westmark PR, Beard AM, Hildebrandt SM, Malter JS. Seizure susceptibility and mortality in mice that over-express amyloid precursor protein. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2008;1:157–168. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan QJ, Rammal M, Tranfaglia M, Bauchwitz RP. Suppression of two major fragile X syndrome mouse model phenotypes by the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49:1053–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costantini C, Weindruch R, Della Valle G, Pug-lielli L. ATrkA-to-p75NTR molecular switch activates amyloid beta-peptide generation during aging. Biochem J. 2005;391:59–67. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh K, Gaur P, Prasad S. Fragile x mental retardation (fmr-1) gene expression is down regulated in brain of mice during aging. Mol Biol Rep. 2006 doi: 10.1007/s11033-006-9032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bear MF, Huber KM, Warren ST. The mGluR theory of fragile X mental retardation. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:370–377. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gasparini F, Lingenhohl K, Stoehr N, Flor PJ, Heinrich M, Vranesic I, Biollaz M, Allgeier H, Heckendorn R, Urwyler S, Varney MA, Johnson EC, Hess SD, Rao SP, Sacaan AI, Santori EM, Velicelebi G, Kuhn R. 2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)-pyridine (MPEP), a potent, selective and systemically active mGlu5 receptor antagonist. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:1493–1503. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varney MA, Cosford ND, Jachec C, Rao SP, Sacaan A, Lin FF, Bleicher L, Santori EM, Flor PJ, Allgeier H, Gasparini F, Kuhn R, Hess SD, Velicelebi G, Johnson EC. SIB-1757 and SIB-1893: Selective, noncompetitive antagonists of metabotropic glutamate receptor type 5. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;290:170–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang RQ, Bell-Horner CL, Dibas MI, Covey DF, Drewe JA, Dillon GH. Pentylenetetrazole-induced inhibition of recombinant gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABA(A)) receptors: Mechanism and site of action. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298:986–995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Del Vecchio RA, Gold LH, Novick SJ, Wong G, Hyde LA. Increased seizure threshold and severity in young transgenic CRND8 mice. Neurosci Lett. 2004;367:164–167. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.05.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khandjian EW, Fortin A, Thibodeau A, Tremblay S, Cote F, Devys D, Mandel JL, Rousseau F. A heterogeneous set of FMR1 proteins is widely distributed in mouse tissues and is modulated in cell culture. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:783–789. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.5.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu R, Wang H, Liang Z, Ku L, O'Donnell W T, Li W, Warren ST, Feng Y. The fragile X protein controls microtubule-associated protein 1B translation and microtubule stability in brain neuron development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:15201–15206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404995101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hung AY, Koo EH, Haass C, Selkoe DJ. Increased expression of beta-amyloid precursor protein during neuronal differentiation is not accompanied by secretory cleavage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:9439–9443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loffler J, Huber G. Beta-amyloid precursor protein isoforms in various rat brain regions and during brain development. J Neurochem. 1992;59:1316–1324. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb08443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masliah E, Mallory M, Ge N, Saitoh T. Amyloid precursor protein is localized in growing neu-rites of neonatal rat brain. Brain Res. 1992;593:323–328. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91329-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moya KL, Benowitz LI, Schneider GE, Allinquant B. The amyloid precursor protein is develop-mentally regulated and correlated with synap-togenesis. Dev Biol. 1994;161:597–603. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torroja L, Packard M, Gorczyca M, White K, Budnik V. The drosophila beta-amyloid precursor protein homolog promotes synapse differentiation at the neuromuscular junction. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7793–7803. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-18-07793.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mucke L, Masliah E, Johnson WB, Ruppe MD, Alford M, Rockenstein EM, Forss-Petter S, Pietropaolo M, Mallory M, Abraham CR. Synaptotrophic effects of human amyloid beta protein precursors in the cortex of transgenic mice. Brain Res. 1994;666:151–167. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90767-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herard AS, Besret L, Dubois A, Dauguet J, Delzescaux T, Hantraye P, Bonvento G, Moya KL. siRNA targeted against amyloid precursor protein impairs synaptic activity in vivo. Neurobiol Aging. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang P, Yang G, Mosier DR, Chang P, Zaidi T, Gong YD, Zhao NM, Dominguez B, Lee KF, Gan WB, Zheng H. Defective neuromuscular synapses in mice lacking amyloid precursor protein (APP) and APP-like protein 2. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1219–1225. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4660-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mileusnic R, Lancashire CL, Rose SP. Amyloid precursor proteFrom synaptic plasticity to alzheimer's disease. Ann N YAcad Sci. 2005;1048:149–165. doi: 10.1196/annals.1342.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doyle E, Bruce MT, Breen KC, Smith DC, Anderton B, Regan CM. Intraventricular infusions of antibodies to amyloid-beta-protein precursor impair the acquisition of a passive avoidance response in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1990;115:97–102. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90524-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsiao K, Chapman P, Nilsen S, Eckman C, Harigaya Y, Younkin S, Yang F, Cole G. Correlative memory deficits, abeta elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science. 1996;274:99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.An JJ, Gharami K, Liao GY, Woo NH, Lau AG, Vanevski F, Torre ER, Jones KR, Feng Y, Lu B, Xu B. Distinct role of long 3′ UTR BDNF mRNA in spine morphology and synaptic plasticity in hippocampal neurons. Cell. 2008;134:175–187. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blichenberg A, Rehbein M, Muller R, Garner CC, Richter D, Kindler S. Identification of a cis-acting dendritic targeting element in the mRNA encoding the alpha subunit of Ca2+/ calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:1881–1888. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blichenberg A, Schwanke B, Rehbein M, Garner CC, Richter D, Kindler S. Identification of a cis-acting dendritic targeting element in MAP2 mRNAs. J Neurosci. 1999;19:8818–8829. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-20-08818.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kobayashi H, Yamamoto S, Maruo T, Murakami F. Identification of a cis-acting element required for dendritic targeting of activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein mRNA. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:2977–2984. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Vrij FM, Levenga J, van der Linde HC, Koek-koek SK, De Zeeuw CI, Nelson DL, Oostra BA, Willemsen R. Rescue of behavioral phenotype and neuronal protrusion morphology in Fmr1 KO mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;31:127–132. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McBride SM, Choi CH, Wang Y, Liebelt D, Braunstein E, Ferreiro D, Sehgal A, Siwicki KK, Dockendorff TC, Nguyen HT, McDonald TV, Jongens TA. Pharmacological rescue of synaptic plasticity, courtship behavior, and mushroom body defects in a drosophila model of fragile X syndrome. Neuron. 2005;45:753–764. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chapman AG, Nanan K, Williams M, Meldrum BS. Anticonvulsant activity of two metabotropic glutamate group I antagonists selective for the mGlu5 receptor: 2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)-pyridine (MPEP), and (E)-6-methyl-2-styryl-pyridine (SIB 1893) Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:1567–1574. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00242-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee AC, Wong RK, Chuang SC, Shin HS, Bianchi R. Role of synaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors in epileptiform discharges in hippocampal slices. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:1625–1633. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.4.1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Merlin LR. Differential roles for mGluR1 and mGluR5 in the persistent prolongation of epileptiform bursts. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:621–625. doi: 10.1152/jn.00579.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jesse CR, Savegnago L, Rocha JB, Nogueira CW. Neuroprotective effect caused by MPEP, an antagonist of metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR5, on seizures induced by pilo-carpine in 21-day-old rats. Brain Res. 2008;1198:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nagaraja RY, Grecksch G, Reymann KG, Schroeder H, Becker A. Group I metabotropic glutamate receptors interfere in different ways with penty-lenetetrazole seizures, kindling, and kindling-related learningdeficits. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2004;370:26–34. doi: 10.1007/s00210-004-0942-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zaidi SH, Malter JS. Amyloid precursor protein mRNA stability is controlled by a 29-base element in the 3′-untranslated region. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:24007–24013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zaidi SH, Malter JS. Nucleolin and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein C proteins specifically interact with the 3′-untranslated region of amyloid protein precursor mRNA. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17292–17298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Westmark PR, Shin HC, Westmark CJ, Soltaninassab SR, Reinke EK, Malter JS. Decoy mRNAs reduce beta-amyloid precursor protein mRNA in neuronal cells. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27:787–796. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ceman S, Brown V, Warren ST. Isolation of an FMRP-associated messenger ribonucleoprotein particle and identification of nucleolin and the fragile X-related proteins as components of the complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7925–7932. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.7925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ceman S, Nelson R, Warren ST. Identification of mouse YB1/p50 as a component of the FMRP-associated mRNP particle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;279:904–908. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]