Abstract

The safety of silicone-based implant for mammoplasty has been debated for decades. A series of anecdotal case reports and a recent epidemiological case-control study have suggested a possible association between silicone implant and the development of primary breast ALK1-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), a rare type of peripheral T-cell lymphoma. In this report, we describe an additional case of primary breast ALK1-negative ALCL in the fibrous capsule and cystic fluid of silicone breast implant in a 58 year old woman who underwent breast reconstructive surgery after lumpectomy for her infiltrating breast adenocarcinoma. Morphologically and immunohistochemically, the lymphoma cells may be confused with recurrent infiltrating breast adenocarcinoma or other non-hematolymphoid malignancies. Molecular studies were needed to determine T-lineage differentiation of the malignant lymphoma cells. We will also review the case reports and case series published in the English literature and discuss our current understanding of silicone implant in primary breast ALK1-negative ALCL.

Keywords: Breast implant, silicone, anaplastic large cell lymphoma, ALK1, ALCL

Introduction

Primary breast lymphoma is uncommon, comprising less than 1% of all primary breast malignancies and about 2% of all extranodal nonHodgkin lymphomas [1, 2]. The majority of primary breast lymphomas are of B-cell origin, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, follicle center cell lymphoma and other B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders [1–3]. Primary breast T-cell lymphoma is even rarer, comprising less than 10% of all primary breast non-Hodgkin lymphomas [1, 2, 4]. In fact, in a recent study by Lin YC et al, there was no single case of primary breast T-cell lymphoma in one of the largest series reported from Taiwan [5].

Silicone-based implant for breast augmentation is primarily used in women for cosmetic purpose. It has also been used in patients after lumpectomy or mastectomy for breast cancer [6]. The safety of this procedure has been debated for decades, particularly its association with connective tissue disorders. In the last decade or so, attention has been shifted to the long term effect of silicone implant on cancer development. A single epidemiological study reported an increased risk of cancer death among women with silicone breast implants compared with women in the general population [7]. Several large epidemiological studies, however, have subsequently shown no evidence of increased risk of developing malignancy in the breast or other tissues after breast augmentation with silicone implant, perhaps with the exception of lung cancer [8–10].

ALK1-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) is a rare peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Anecdotal case reports and a recent large retrospective epidemiological case-control study from Sweden have raised concern of silicone implant in the development of lymphoma [4, 11–21]. Here we describe another case of primary breast ALK1-negative ALCL in association with silicone breast implant and review the literature to discuss our current understanding of silicone implant in primary breast lymphomas.

Report of a case

The patient was a 58 year old woman with a history of small infiltrating ductal carcinoma (less than 5 mm in maximum diameter) of her left breast diagnosed in November 2002. She underwent lumpectomy followed by treatment with tamoxifen and cosmetic breast reconstructive surgery with a silicone-based saline-filled implant. About five and a half years following the surgery, she was found to have left breast swelling with a painless mass. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the chest showed fluid collection around her implant.

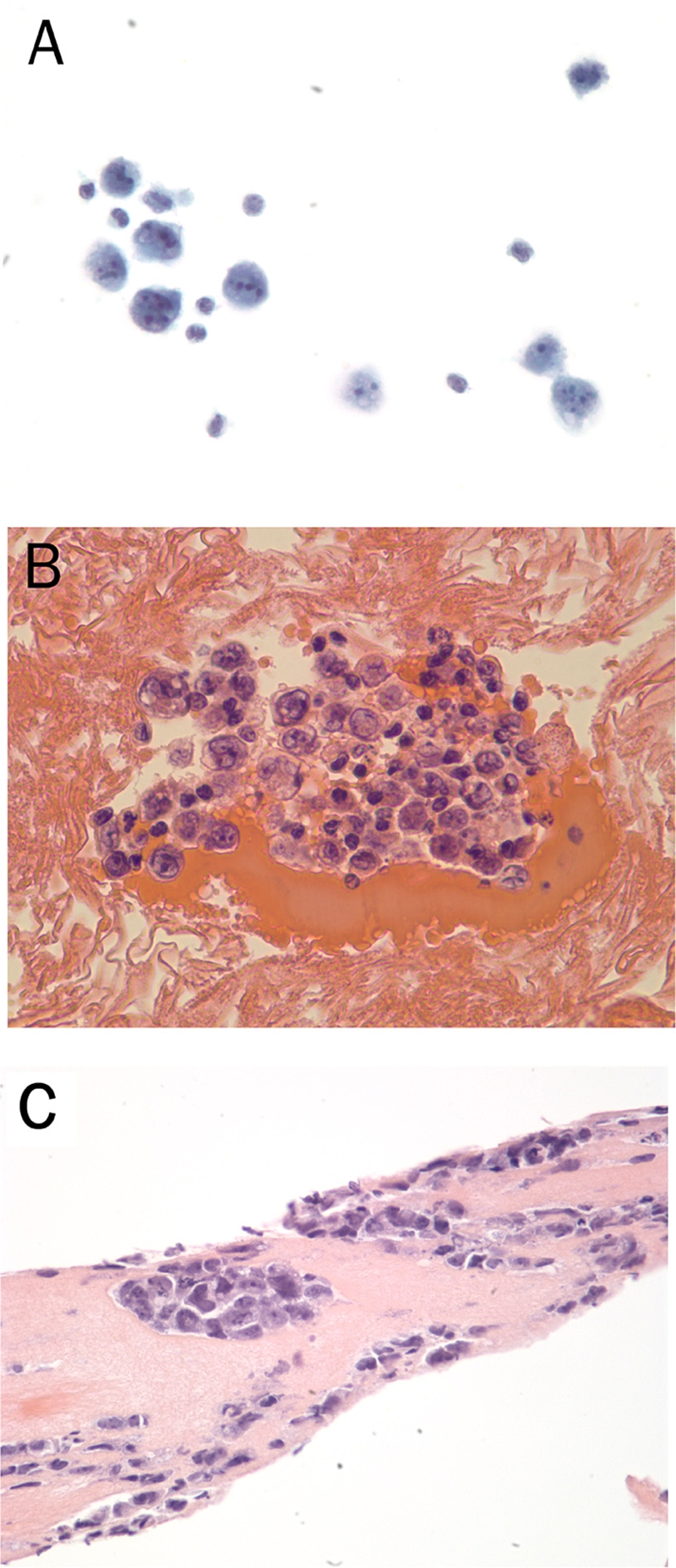

Fine needle aspiration of the fluid around the breast implant showed large atypical mononuclear cells with irregular nuclear contours and prominent nucleoli in a background of small lymphocytes (Figure 1A), suspicious for recurrence of the patient's infiltrating ductal carcinoma. The implant was then surgically removed and submitted for pathological examination. The implant was grossly intact surrounded by a fibrous capsule. Sections of the cell block from the fine needle aspiration and the fibrous capsule both demonstrated the presence of large atypical mononuclear cells forming cohesive clusters (Figures 1B and 1C), again raising the diagnostic consideration of recurrent breast adenocarcinoma.

Figure 1.

Cytological and histological features of the primary breast ALK1-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma from the fine needle aspirate smear (A, PAP staining, 40x), cell block (B, H&E staining, 40x) and fibrous capsule of the excisional biopsy (C, H&E staining, 40x). The lymphoma cells are large with irregular contours and prominent nucleoli that are often arranged in clusters and sheets in the fibrous capsule.

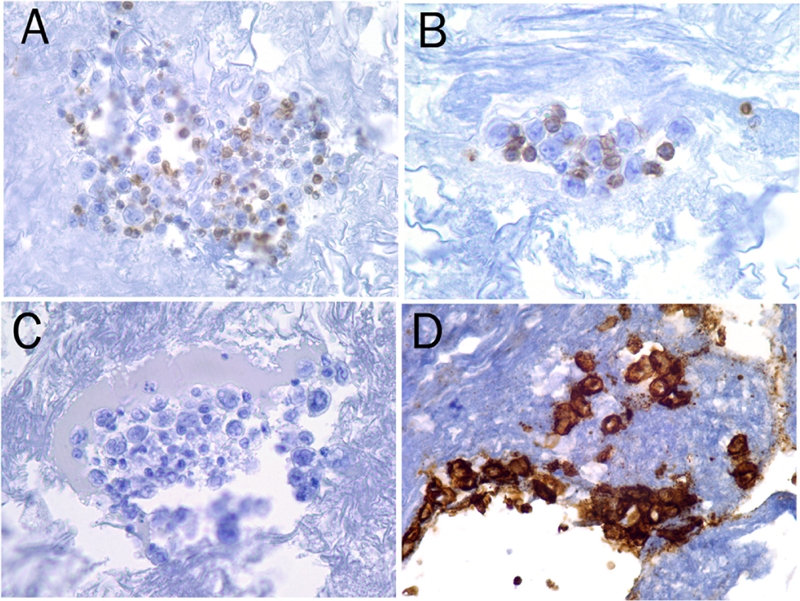

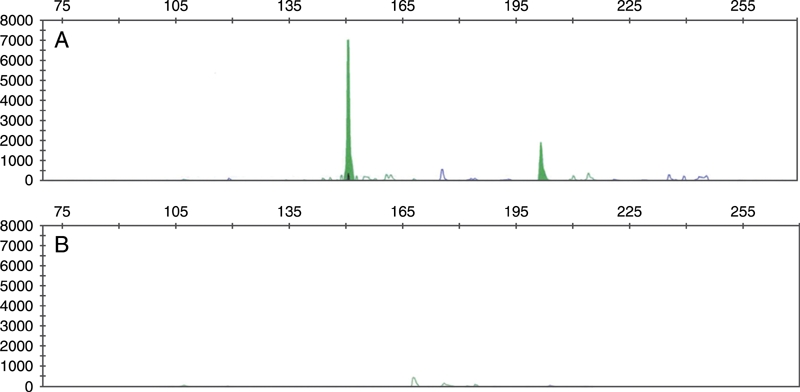

Immunohistochemical stains were performed on the cell block as well as the seroma. The atypical mononuclear cells were positive for CD30, but negative for CD3, CD20 and CD45 (Figure 2). Epithelial membrane protein (EMA) was also positive (data not shown). The malignant cells are negative for keratin (AE1/AE3), S100, CD68, HMB45, CD5, CD79a, CD138, kappa, lambda, and ALK. Fluorescence in situ hybridization studies with the ALK breakapart probe was also negative for ALK gene rearrangement (data not shown). Even though immunostain for keratin was negative, the possibility of recurrent breast adenocarcinoma cannot be completely excluded because of the patient's history and lineage non-specificity of CD30 and EMA. Therefore, molecular studies were performed and the results demonstrated monoclonal rearrangement of the T-cell receptor gamma gene without evidence of monoclonality of B cells (Figure 3). The morphologic, immunohistochemical and molecular findings support a diagnosis of ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma arising in association with silicone breast implant rather than recurrent infiltrating breast cancer or other nonhematolymphoid malignancies.

Figure 2.

The malignant lymphoma cells are negative for CD45 (A), CD3 (B), CD20 (C), butpositive for CD30 (D) as shown by immunohistochemical stain using Dako Auto-stainer (magnification, 40x).

Figure 3.

Polymerase chain reaction analysis demonstrated monoclonal rearrangement of the T-cell receptor gamma gene (A), but not the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene (B) using kits from InVivoScribe Technologies (San Diego, CA).

Physical examination and computerized tomography scans showed no evidence of lymphadenopathy or organomegaly. A complete blood count with differential was normal. A staging bone marrow biopsy was negative for involvement by malignant lymphoma or metastatic disease. She was treated with 6 cycles of CHOP (cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine and prednisone) and had no evidence of disease 10 months after treatment.

Discussion

More than 1 million mammoplasty procedures have been performed in the United States since the silicone-based implant was first marketed in 1962. Most procedures were performed to augment breasts for cosmetic reason and some were performed post mastectomy or lumpectomy in patients with breast cancer. The safety of this product has been debated for decades. Early studies suggested an association between silicone breast implant and chronic connective tissue disorders because implant recipients produced autoantibodies against silicone.

The risk of developing cancer in breast and other tissues has been the focus of attention the last decade or so because a retrospective epidemiological study reported a higher risk of cancer-related death among women with silicone breast implants compared with women in the general population [7, 8]. However, subsequent large epidemiological studies demonstrated no evidence of increased cancer risk in association with silicone breast implant. In fact, the standard incidence rate for breast cancer is lower in silicone breast implant recipients than in the general population [9, 10]. There might be a slightly increased risk of lung cancer in the recipient population, which may have been related to other factors such as history of smoking and urban indwelling environment rather than silicone breast mammoplasty per se.

The possible association between silicone implant and primary breast nonHodgkin lymphoma was first suggested by Duvic et al in 1995 [24]. The authors reported three cases of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) in association with breast implant. However, CTCL is such a common cutaneous lymphoma that reporting of 3 cases among the more than 1 million breast implant recipients could have been coincidental.

ALK1-negative ALCL is a rare peripheral T-cell lymphoma and a provisional entity in the most recent WHO classification of hematolymphoid neoplasms. The first case of ALCL in association with a saline-filled breast implant was reported by Keech and Creech in 1997 [14]. The patient was 41 year-old white female who developed ALCL 5 years after cosmetic silicone breast augmentation for postpartum mammary hypoplasia. ALK1 expression was not described. She was successfully treated with chemotherapy without evidence of recurrent disease. Among the 30 cases of primary breast ALCL reported in the English literature so far, 22 of them were associated with silicone-based implant, including the case reported here and one large series from Sweden (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of primary breast ALCL reported in the English literature

| References | Case | Age/sex | Laterality | Initial clinical presentation | Immunophenotype/genotype | ALK1 status | Implant types | Time interval (years) and purpose | Treatment outcome (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gualco et al [4, 11] | 1 | 28/F | L | Mastitis | CD30+, others unknown; TCR+ | Negative | Silicone | 6; cosmetic | Alive without disease (40) |

| 2 | Unknown/F | R | N/A | CD30+, others unknown | N/A | No | N/A | N/A | |

| 3 | 65/M | R | 3 cm mass | CD30+, other unknown; TCR+ | Positive | No | N/A | Alive (18) | |

| Alobeid et al [12] | 1 | 68/F | R | Lymphadenopathy | Positive for CD15, CD30, EMA, MUM1, CD2, CD4. Ki-67>90%. Negative for others; TCR+; Complex karyotype. | Negative | Silicone | 16; modified radical mastectomy for infiltrating ductal carcinoma followed by CT | s/p CT; alive with disease (4) |

| Bishara et al [13] | 1 | 66/F | L | Breast edema, tenderness and contraction without a mass lesion | Focally positive for LCA and EMA, CD30++, vimentin+. Negative for others.TCR+ | Negative | Saline-filled silicone | 12; modified radical mastectomy for infiltrating ductal carcinoma followed by CT | s/p CT and RT; alive without disease (18) |

| Keech et al [14] | 1 | 41/F | L | Implant deflation with a 2 cm mass lesion | CD30+, others unknown | N/A | Saline-filled silicone | 5; cosmetic for postpartum mammary hypoplasia | s/p CT + RT, alive without disease (unknown) |

| Guo et al [15] | 1 | Unknown/F | Unknown | Unknown | CD30+, other unknown | N/A | No | N/A | N/A |

| Wong et al [16] | 1 | 40/F | R | Bilateral breast contraction and asymmetry | Positive for CD30, EMA and CD4. Negative for others. TCR+ | Negative | Silicone | 21; cosmetic, bilateral | s/p CT, followup info not available |

| Fritzsche et al [17] | 1 | 72/F | L | 2.5 cm skin ulceration | Positive for CD30, weakly positive for CD4, CD5, CD56. Ki67>80%. Negative for others. | Negative | Silicone | 16; mastectomy for breast cancer | No treatment, followup not available |

| Newman et al [18] | 1 | 52/F | R | Capsular contraction and swelling with fluid collection | CD30+, others unknown | Unknown | Silicone | 14; cosmetic | s/p CT without disease (14) |

| Sahoo et al [19] | 1 | 33/F | L | Swelling and tenderness | Positive for CD30, CD2, CD43, and EMA, Negative for others | Negative | Silicone | 4; cosmetic | s/p CT + RT without disease (12) |

| Olack et al [20] | 1 | 56/F | R | Enlargement | CD30+, others unknown | Negative | Saline-filled silicone | 7; breast cancer | s/p CT + RT, alive without disease (19) |

| Gaudet et al [21] | 1 | 87/F | R | Mass lesion | Positive for CD30, CD45, CD4, CD43, CD45RO, CD5, CD8, TIA-1, EMA; Negative for others; TCR+. | Negative | Saline-filled silicone | 7; mastectomy for breast cancer | N/A |

| 2 | 50/F | L | Mass lesion | CD30+, CD45+, CD2+, CD3+, CD5+, CD43+, TCR+. Negative for other markers | Negative | Silicone | 9; cosmetic. History of HL 20 years prior to implant | s/p CT; relapsed (12) as systemic ALCL | |

| Roden et al [22] | 1 | 45/F | R | Seroma | Positive for CD30, CD4, CD5, CD43, CD45, TIA1, EMA, TCR. Others negative | Negative | Saline-filled silicone | 7; mastectomy for breast cancer | No treatment. Alive without disease (20) |

| 2 | 59/F | L | Seroma | Positive for CD30, CD2, CD3,CD8, CD43, CD45, TIA1, EMA, Negative for others; TCR- | Negative | Silicone | 3; mastectomy for breast cancer | s/p RT only. Alive without disease (10) | |

| 3 | 34/F | L | Seromo | Positive for CD30, CD2, CD45, TIA1, EMA, TCR. Others negative | Negative | Saline-filled silicone | 4; cosmetic bilateral breast augmentation | s/p CT and RT. Alive without disease (9) | |

| 4 | 44/F | L | Seroma | Positive for CD30, CD4, CD5, CD45, CD43, TIA1, EMA; Negative for others; TCR+ | Negative | Saline-filled silicone | Information not available | N/A | |

| De Long et al [23] | 1 | 41/F | L | Unknown | Positive for CD30; others unknown; TCR+. | Negative | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2 | 38/F | L | Unknown | Positive for CD30; others unknown; TCR+. | Negative | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 3 | 61/F | R/L | Unknown | Positive for CD30; others unknown; TCR+. | Negative | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 4 | 31/F | R | Unknown | Positive for CD30; others unknown; TCR+. | Negative | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 5 | 68/F | R | Unknown | Positive for CD30; others unknown; TCR+. | Negative | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 6 | 53/F | L | Unknown | Positive for CD30; others unknown; TCR+. | Negative | Silicone | 1; cosmetic | N/A | |

| 7 | 49/F | R/L | unknown | Positive for CD30; others unknown; TCR+. | Negative | Silicone | 23; cosmetic | N/A | |

| 8 | 43/F | R | Unknown | Positive for CD30; others unknown; TCR+. | Negative | Silicone | 13; cosmetic | N/A | |

| 9 | 29/F | R | Unknown | Positive for CD30; others unknown; TCR+. | Negative | silicone | 3; cosmetic | N/A | |

| 10 | 38/F | R | Unknown | Positive for CD30; others unknown; TCR+. | Negative | unknown | 13; cosmetic | N/A | |

| 11 | 24/F | R/L | unknown | Positive for CD30; others unknown; TCR+. | Negative | unknown | Unknown; cosmetic | N/A | |

| This report | 1 | 58/F | L | Seroma | CD30+, EMA+; Negative for others; TCR+ | Negative | Saline-filled silicone | 6; mastectomy for breast cancer | s/p CT and RT, alive without disease (10) |

TCR, T-cell receptor gene rearrangement; CT, chemotherapy; RT, radiation therapy; R, right; L, left.

Primary breast lymphoma typically presents with a mass lesion, including primary breast ALCL not associated with silicone implant. Most patients with primary breast ALCL associated with silicone implant, however, presented with implant-related symptoms with or without a mass lesion, with seroma as the most common presentation. This unusual presentation indicates the importance of careful pathological examination of tissues removed for implant-related complications. In implant-associated primary breast ALCL, both sides are equally affected, which is different from the reported predilection for involvement of the right breast by other types of primary breast lymphomas. The age of patients with implant-related ALCL ranged from 24 to 87 years, and lymphoma developed 1 to 23 years after mammoplasty surgery. Slightly more than half of the procedures were performed for cosmetic reason, while the remainders were for breast cancer (Table 1).

The lymphoma cells in primary breast ALCL with or without association of silicone implant were morphologically similar. The lymphoma cells demonstrate bulky eosinophilic to amphophilic cytoplasm, and the nuclei are large and pleomorphic with vesicular chromatin and prominent nucleoli (Figure 1). Mitoses are frequently seen, and the proliferation index in cases assessed with Ki6-7 is high (>80% in the cases examined). Like nodal ALCL, these cells tend to form cohesive sheets in the fibrous capsule of the silicone implant, mimicking invasive carcinoma. Horseshoe-like hallmark cells may also be seen. There was no skin involvement in all reported cases. The lymphoma cells are also present in the fluid collection surrounding the intact or leaky implant.

Immunohistochemically, primary breast ALCL cells are uniformly and strongly positive for CD30 with both membrane and Golgi staining (Figure 2), and are mostly positive for EMA in the cases evaluated. Most cases demonstrated expression of at least one T-cell marker, such as CD3, CD4, CD5, CD7 or CD43, a feature that can be used to distinguish ALCL from recurrent infiltrating breast adenocarcinoma and other nonhematolymphoid malignancies. TIA1, cytotoxic granule protein, is positive in a subset of cases examined. However, molecular studies to demonstrate clonal rearrangement of the T-cell receptor gene are essential to confirm the diagnosis. Except for one, all primary breast ALCL demonstrated clonal rearrangement of the T-cell receptor gene in the cases analyzed (Figure 3). Immunoglobulin heavy chain gene rearrangement is not present. ALK1 expression was absent in all ALCL associated with silicone breast implant reported to date by immunohistochemical stains and, in a few cases, by cytogenetic techniques including fluorescence in situ hybridization.

Clinical follow-up was available in only about half of the patients with primary breast ALCL associated with silicone implant (Table 1). Most of these patients received chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy. Some patients were followed with observation only after removal of the seroma and silicone implant. Except for one with recurrent disease 12 months later, all patients were in remission without disease during the follow-up period, suggesting a relatively indolent disease of primary breast ALCL associated with silicone implant.

ALCL with secondary breast involvement has also been reported. Talwalkar et al described 2 ALK1-negative ALCL with secondary involvement of the breast [2]. One patient had a history of lymphomatoid papulosis and classical Hodgkin lymphoma. When breast involvement was diagnosed, the patient had systemic involvement of skin, lung, lymph node and bone marrow. The patient died 36 months after the diagnosis. The second patient had a history of cutaneous ALCL before developing ALK1-negative ALCL of the breast. She was alive without evidence of disease with 5 months of follow-up. Interestingly, both cases were associated with silicone breast implant. They also reported 4 cases of ALK1-positive ALCL with secondary breast involvement, and none of these 4 cases were in association with breast implant.

Though primary breast lymphomas are most commonly of B-cell origin, only three B cell lymphomas have been described in association with breast implant. These are follicular lymphoma [25], primary effusion lymphoma [26], and lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma [27]. There was no single case report of primary breast diffuse large B-cell lymphoma arising in association with breast implant. If the association between silicone implant and primary breast lymphoma is by chance alone, one would expect to observe more primary breast B cell lymphomas than primary breast ALK1-negative ALCL in association with silicone mammoplasty since silicone implant has been widely used and ALK-negative ALCL is such an uncommon lymphoma.

It appears that silicone implant may play a role in the development of primary breast ALK1-negative ALCL. The underlying mechanism of this possible link is unknown. Chemotherapy for breast cancer has been shown to increase the risk of secondary cancer development, such as Hodgkin lymphoma and myeloid neoplasm. Less than half of the silicone-associated primary breast ALK1-negative ALCL had the mammoplasty performed after lumpectomy or mastectomy of breast cancer. It is unlikely that these lymphomas are due to chemotherapy for the underlying breast cancer. Silicone has been shown to incite chronic inflammatory response with production of autoantibodies. Since chronic inflammation has been associated with development of malignant lymphomas, such as H. pylori infection in gastric extranodal marginal zone lymphoma and hepatitis C infection in marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, it is possible that chronic inflammatory stimulation may be related to the increased risk of development of primary breast ALK1-negative ALCL in silicone implant recipients.

It should be noted the wide range of odds ratio in the retrospective case control study by de Jong et al [23]. 5 of the 11 primary breast ALK1-negative ALCLs had no history of silicone breast implantation [23]. One of the patients developed ALCL 1 year after cosmetic implantation. These facts also raise the possibility of random association between silicone implant and primary breast ALK1-negative ALCL. Further studies are necessary to confirm or repute the causal association between silicone implant and primary breast ALK1-negative ALCL. Laboratory investigation is also needed to identify the underlying molecular mechanism, particularly the role of chronic inflammatory stimulation in lymphomagenesis, if the association does exist.

References

- 1.Validire P, Capovilla M, Asselain B, Kirova Y, Goudefroye R, Plancher C, Fourquet A, Zanni M, Gaulard P, Vincent-Salomon A, Decaudin D. Primary breast non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a large single center study of initial characteristics, natural history, and prognostic factors. Am J Hematol. 2009;84(3):133–9. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Talwalkar SS, Miranda RN, Valbuena JR, Routbort MJ, Martin AW, Medeiros LJ. Lymphomas involving the breast: a study of 106 cases comparing localized and disseminated neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32(9):1299–309. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318165eb50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinelli G, Ryan G, Seymour JF, Nassi L, Steffanoni S, Alietti A, Calabrese L, Pruneri G, Santoro L, Kuper-Hommel M, Tsang R, Zinzani PL, Taghian A, Zucca E, Cavalli F. Primary follicular and marginal-zone lymphoma of the breast: clinical features, prognostic factors and outcome: a study by the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group. Ann Oncol. 2009 Jul 1; doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp238. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gualco G, Chioato L, Harrington WJ, Jr, Weiss LM, Bacchi CE. Primary and secondary T-cell lymphomas of the breast: clinico-pathologic features of 11 cases. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2009;17(4):301–6. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e318195286d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin YC, Tsai CH, Wu JS, Huang CS, Kuo SH, Lin CW, Cheng AL. Clinicopathologic features and treatment outcome of non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the breast–a review of 42 primary and secondary cases in Taiwanese patients. Leuk Lymphoma. 2009;50(6):918–24. doi: 10.1080/10428190902777475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rozen WM, Rajkomer AK, Anavekar NS, Ashton MW. Post-mastectomy breast reconstruction: a history in evolution. Clin Breast Cancer. 2009;9(3):145–54. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2009.n.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brinton LA, Brown SL. Breast implants and cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89(18):1341–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.18.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brinton LA, Lubin JH, Burich MC, Colton T, Hoover RN. Mortality among augmentation mammoplasty patients. Epidemiology. 2001;12(3):321–6. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200105000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McLaughlin JK, Lipworth L, Fryzek JP, Ye W, Tarone RE, Nyren O. Long-term cancer risk among Swedish women with cosmetic breast implants: an update of a nationwide study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(8):557–60. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lipworth L, Tarone RE, McLaughlin JK. Breast implants and lymphoma risk: a review of the epidemiologic evidence through 2008. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123(3):790–3. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318199edeb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gualco G, Bacchi CE. B-cell and T-cell lymphomas of the breast: clinical–pathological features of 53 cases. Int J Surg Pathol. 2008;16(4):407–13. doi: 10.1177/1066896908316784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alobeid B, Sevilla DW, El-Tamer MB, Murty VV, Savage DG, Bhagat G. Aggressive presentation of breast implant-associated ALK-1 negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma with bilateral axillary lymph node involvement. Leuk Lymphoma. 2009;50(5):831–3. doi: 10.1080/10428190902795527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bishara MR, Ross C, Sur M. Primary anaplastic large cell lymphoma of the breast arising in reconstruction mammoplasty capsule of saline filled breast implant after radical mastectomy for breast cancer: an unusual case presentation. Diagn Pathol. 2009;4:11. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-4-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keech JA, Jr, Creech BJ. Anaplastic T-cell lymphoma in proximity to a saline filled breast implant. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100(2):554–5. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199708000-00065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo HY, Zhao XM, Li J, Hu XC. Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the breast: eight-year follow-up experience. Int J Hematol. 2008;87(5):491–7. doi: 10.1007/s12185-008-0085-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong AK, Lopategui J, Clancy S, Kulber D, Bose S. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma associated with a breast implant capsule: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008 Aug;32(8):1265–8. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318162bcc1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fritzsche FR, Pahl S, Petersen I, Burkhardt M, Dankof A, Dietel M, Kristiansen G. Anaplastic large-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the breast in periprosthetic localisation 32 years after treatment for primary breast cancer–a case report. Virchows Arch. 2006;449(5):561–4. doi: 10.1007/s00428-006-0287-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newman MK, Zemmel NJ, Bandak AZ, Kaplan BJ. Primary breast lymphoma in a patient with silicone breast implants: a case report and review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61(7):822–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2007.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sahoo S, Rosen PP, Feddersen RM, Viswanatha DS, Clark DA, Chadburn A. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma arising in a silicone breast implant capsule: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003 Mar;127(3):e 115–8. doi: 10.5858/2003-127-e115-ALCLAI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olack B, Gupta R, Brooks GS. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma arisingin a saline breastimplant capsule after tissue expander breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;59(1):56–7. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31804d442e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaudet G, Friedberg JW, Weng A, Pinkus GS, Freedman AS. Breast lymphoma associated with breast implants: two case-reports and a review of the literature. Leuk Lymphoma. 2002;43(1):115–9. doi: 10.1080/10428190210189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roden AC, Macon WR, Keeney GL, Myers JL, Feldman AL, Dogan A. Seroma-associated primary anaplastic large-cell lymphoma adjacent to breast implants: an indolent T-cell lympho-proliferative disorder. Mod Pathol. 2008;21(4):455–63. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3801024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Jong D, Vasmel WL, de Boer JP, Verhave G, Barbé E, Casparie MK, van Leeuwen FE. Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma in women with breast implants. JAMA. 2008;300(17):2030–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duvic M, Moore D, Menter A, Vonderheid EC. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in association with silicone breast implants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32(6):939–42. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)91328-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cook PD, Osborne BM, Connor RL, Strauss JF. Follicular lymphoma adjacent to foreign body granulomatous inflammation and fibrosis surrounding silicone breast prosthesis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19(6):712–7. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199506000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Said JW, Tasaka T, Takeuchi S, Asou H, de Vos S, Cesarman E, Knowles DM, Koeffler HP. Primary effusion lymphoma in women: report of two cases of Kaposi's sarcoma herpes virus-associated effusion-based lymphoma in human immunodeficiency virus-negative women. Blood. 1996;88(8):3124–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kraemer DM, Tony HP, Gattenlöhner S, Müller JG. Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma in a patient with leaking silicone implant. Haematologica. 2004;89(4):ELT01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]