Abstract

Several studies have demonstrated an association between polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and the dinucleotide repeat microsatellite marker D19S884, which is located in intron 55 of the fibrillin-3 (FBN3) gene. Fibrillins, including FBN1 and 2, interact with latent transforming growth factor (TGF)-β-binding proteins (LTBP) and thereby control the bioactivity of TGFβs. TGFβs stimulate fibroblast replication and collagen production. The PCOS ovarian phenotype includes increased stromal collagen and expansion of the ovarian cortex, features feasibly influenced by abnormal fibrillin expression. To examine a possible role of fibrillins in PCOS, particularly FBN3, we undertook tagging and functional single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis (32 SNPs including 10 that generate non-synonymous amino acid changes) using DNA from 173 PCOS patients and 194 controls. No SNP showed a significant association with PCOS and alleles of most SNPs showed almost identical population frequencies between PCOS and control subjects. No significant differences were observed for microsatellite D19S884. In human PCO stroma/cortex (n = 4) and non-PCO ovarian stroma (n = 9), follicles (n = 3) and corpora lutea (n = 3) and in human ovarian cancer cell lines (KGN, SKOV-3, OVCAR-3, OVCAR-5), FBN1 mRNA levels were approximately 100 times greater than FBN2 and 200–1000-fold greater than FBN3. Expression of LTBP-1 mRNA was 3-fold greater than LTBP-2. We conclude that FBN3 appears to have little involvement in PCOS but cannot rule out that other markers in the region of chromosome 19p13.2 are associated with PCOS or that FBN3 expression occurs in other organs and that this may be influencing the PCOS phenotype.

Keywords: fibrillin, latent-transforming growth factor β-binding protein, polycystic ovary syndrome, ovary

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a common endocrine disorder that affects an estimated 5–7% of women of reproductive age in western societies and is characterized by hyperandrogenemia, chronic anovulation and polycystic ovaries (Knochenhauer et al., 1998; Diamanti-Kandarakis et al., 1999). Hirsuitism is common among women who suffer from the disorder, and they are at increased risk of anovulatory infertility, obesity (Conway et al., 1989; Balen et al., 1995), hyperlipidaemia and predisposing factors for heart disease (Wild et al., 1985; Wild and Bartholomew, 1988; Slowinska-Srzednicka et al., 1991; Wild et al., 1992; Talbott et al., 1995) and type II diabetes (Knochenhauer et al., 1998; Diamanti-Kandarakis et al., 1999). While the aetiology of PCOS is unknown, familial studies have demonstrated heritability of the disorder, suggesting that there is a genetic component (reviewed in Amato and Simpson, 2004). Female first-degree relatives display strong association between the metabolic abnormalities of PCOS and hyperandrogenemia (Legro et al., 2002; Yildiz et al., 2003), and a recent study demonstrated that the brothers of women with PCOS also have a strong association with metabolic abnormalities (Urbanek et al., 2007). This suggests a common genetic association between the metabolic features of PCOS and hyperandrogenemia, whether that be a defect in the same gene or multiple genes in the same pathway.

The mode of inheritance of PCOS has proven difficult to determine suggesting that the disorder is a complex trait possibly involving multiple genes and/or environmental influences. Many genes in the steroid synthesis pathways (Carey et al., 1994; Gharani et al., 1997), the regulatory pathways of gonadotrophin action (Franks, 1995) and the insulin-signalling pathway have been investigated for association with the disorder. Many of these studies, however, have proven inconclusive or are not reproducible. In contrast, several studies using independent patient cohorts have demonstrated a significant association between PCOS and the dinucleotide repeat microsatellite marker D19S884, which is located 1cM upstream of the insulin receptor (INSR) gene in chromosome region19p13.2 (Tucci et al., 2001; Villuendas et al., 2003; Urbanek et al., 2005; Urbanek et al., 2007). The distance of this marker from INSR casts doubt upon the likelihood of there being a causal genetic variant within INSR and it is more probable that variant(s) in a distal enhancer of INSR or an unrelated gene are the reason for the association between D19S884 and PCOS. D19S884 is located within intron 55 of the fibrillin-3 gene (FBN3).

Fibrillins and latent TGF-β-binding proteins (LTBPs) form a family of proteins that are characterized by a modular domain structure comprising epidermal growth factor-like (EGF) domains, calcium-binding EGF domains and unique cysteine-rich TB domains. Three fibrillin genes, FBN1, 2 and 3 (Sakai et al., 1986; Lee et al., 1991; Corson et al., 2004), and four LTBP genes, LTBP 1, 2, 3 and 4 (Kanzaki et al., 1990; Moren et al., 1994; Yin et al., 1995; Giltay et al., 1997), have been identified in mammals, although in rodents FBN3 has been disrupted due to chromosomal rearrangements (Corson et al., 2004). FBN3 is most highly expressed in human fetal tissues and the human adult brain, eye, lung, adrenal glands, stomach and ovaries (Wheeler et al., 2003; Corson et al., 2004). Studies of FBN1 and 2 have shown that they function as structural components of elastin fibres or mircrofibrils and as regulators of TGF-β family members. Regulation of TGF-β activity by the fibrillins is a result of their ability to bind to LTBPs causing sequestration of latent TGF-βs into the extracellular matrix where they are stored and/or activated (Ramirez and Pereira, 1999; Kielty et al., 2002; Neptune et al., 2003). However, there are subtle differences between them. For instance, LTBP-2 itself does not bind latent TGF-βs (Gibson et al., 1995), but can competitively replace LTBP-1 bound to FBN1 (Hirani et al., 2007). LTBPs are also required for the correct secretion and folding of TGF-βs (Miyazono et al., 1991). To date, interactions between FBN3 and LTBPs have not been investigated. Clinical consequences of the disruption of the interaction between the fibrillins and TGF-βs have been reported previously in the pathogenesis of Marfan's syndrome, a connective tissue disorder affecting the limbs, the heart, the lungs and the eyes. Mutations in FBN1 or the TGF-β type 2 receptor cause Marfan's syndrome (Boileau et al., 2005). The ability of mutations in FBN1 to phenocopy those in TGF-βR type 2 suggests that the structural role of FBN1 in the formation of elastic fibres and microfibrils is less critical to the pathology of the disease than its role in regulating the bioavailability of TGF-β family members.

The involvement of the TGF-β superfamily in the development of PCOS has been implied from functional data (Glister et al., 2005, 2006) and the association of several members, including anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH), activin, inhibin and their associated receptors, as well as follistatin, and the SMADS, has been examined (Urbanek et al., 1999; Urbanek et al., 2000; Kevenaar et al., 2008). Strong association of these genes with PCOS has not been demonstrated, however, it has been suggested that both follistatin, which like fibrillins and LTBPs, contain a TB domain (Thompson et al., 2005), and AMH may contribute to the severity of the PCOS phenotype by influencing androgen levels and/or follicle development (Urbanek et al., 2000; Jones et al., 2007; Kevenaar et al., 2008). Women with PCOS not only display aberrant follicle maturation, but also develop a thickening of the tunica albuginea and stromal tissues of their ovaries that is associated with an increase of collagen deposition in these regions (Hughesdon, 1982). TGF-β superfamily members have been implicated in the regulation of collagen synthesis by fibroblasts in fibroses; TGF-β promotes collagen expression and fibrosis while bone morphogenic protein (BMP)7 suppresses these effects (Govinden and Bhoola, 2003; Wang et al., 2003; Zeisberg et al., 2003; Verrecchia and Mauviel, 2004; Christner and Ayitey, 2006). Hence we have considered the possibility that the fibrillin/LTBP protein family members may be involved in both the gross ovarian morphological and follicular developmental defects associated with PCOS through a disruption in fibrillin-LTBP interactions resulting in perturbations in TGF-β signalling pathways. For these reasons, we chose to undertake a case–control PCOS association test of 32 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within FBN3. We included non-synonymous SNPs located in the coding region of the gene with the aim of identifying PCOS-associated FBN3 variants that may lead to disrupted protein function. We also examined the RNA expression profiles of fibrillin/LTBP family members in human ovarian tissues and cell lines.

Materials and Methods

Subjects for DNA genotyping

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the University of Adelaide Human Research Ethics Committee. Case subjects were recruited from infertility and antenatal clinics at The Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Adelaide, South Australia, after approval by the ethics committee of North Western Adelaide Health Services. Details of a number of these subjects have been reported previously (Milner et al. 1999). The study group represented women of various European cultural backgrounds who generally can be classified as Caucasian. Case subjects consisted of women with PCOS defined as hyperandrogenism and chronic anovulation as per the 1990 NIH consensus criteria (Zawadski and Dunaif, 1992). Polycystic ovaries were identified on ultrasound and defined as the presence of at least eight peripheral cysts less than 10 mm in diameter, with increased ovarian stroma occurring bilaterally (Adams et al., 1986). A total of 367 women between the ages of 18 and 42 were recruited and of these, 173 (47%) women fulfilled the criteria for PCOS. A further 86 patients from the same clinics but who had none of the characteristics of PCOS, and largely male-factor related reasons for infertility, served as controls. An additional 108 patients whose PCO status was unknown were recruited from the female blood donor population (Milner et al., 1999). All samples were de-identified for further analysis.

DNA extraction

Peripheral blood lymphocytes were purified from whole blood using Lymphoprep (Nycomed Pharma, Oslo, Norway) and kept frozen in saline at −20°C until DNA extraction. DNA was extracted from this tissue using a DNeasy Kit (QIAGEN, Chatsworth, CA) as per the manufacturer's protocol, quantified by spectrophotometry and stored at −20°C.

Analyses of SNPs

We typed a single multiplex of 32 tagging and functional SNPs spanning an 82 kb region of FBN3. Tagging SNPs (a set of SNPs that through high linkage disequilibrium (LD) capture the variation in other common SNPs in the region) were chosen using genotyping data from the International HapMap Project (http://www.hapmap.org/) from a population of Caucasian and European background (CEU), having minor allelic frequencies of >0.05 and r2 values of >0.8. Additional functional SNPs that produce a change in protein sequence were chosen to complete the multiplex using genotyping data from the SNP database at the National Library of Medicine (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp), such that they would not interfere with the multiplexing of the tagging SNPs. All SNP sequences were downloaded from the Chip Bioinformatics database (http://snpper.chip.org/) and the sequences were cross checked with the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and Sequenom RealSNP databases (https://www.realsnp.com/) before assay design. Assays were designed for the 32 SNPs using the Sequenom MassARRAY Assay Design software (version 3.1). SNPs were typed using iPLEX ™ Gold chemistry and analysed using a Sequenom MassARRAY Compact Mass Spectrometer (Sequenom Inc, San Diego, CA, USA). The 2.5 µL PCR reactions were performed in standard 384-well plates using 12.5 ng genomic DNA, 0.8 unit of Taq polymerase (HotStarTaq, Qiagen, Valencia, CA), 500 µmol of each dNTP, 1.625 mM of MgCl2 and 100 nmol of each PCR primer (Bioneer, Daejeon, Korea). PCR thermal cycling in an ABI-9700 instrument was 15 min at 94°C, followed by 45 cycles of 20 s at 94°C, 30 s at 56°C and 60 s at 72°C. To the completed PCR reaction, 0.15 U shrimp alkaline phosphatase was added and incubated for 40 min at 37°C followed by inactivation for 5 min at 85°C. A mixture of extension primers was tested to adjust the concentrations of extension primers to equilibrate signal-to-noise ratios in the matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization − time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry prior to use for extension reactions. The post-PCR reactions were performed in a final 5 µl of extension reaction containing 1× termination mix, 1 U DNA polymerase and 570– 1240 nM extension primers. A two-step 200 short cycle programme was used for the iPLEX Gold reaction as described in a previously study (Zhao et al., 2006). The iPLEX reaction products were desalted by diluting samples with 15 µl of water and adding 5 µl of resin (Sequenom Inc, San Diego, CA, USA). The products were spotted on a SpectroChip (Sequenom Inc), and data were processed and analysed by MassARRAY TYPER 3.4 software (Sequenom Inc).

Microsatellite genotyping

To detect microsatellite D19S884 alleles we designed our own primers (Table I) rather than using those suggested for amplimer AFMa299zc5 listed in Genbank as we found these to be unreliable. Primers were designed using Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), from the published genomic sequence of human FBN3 (Table I). The amplification reactions were performed using 50 ng genomic DNA, 1 U of Taq polymerase (AmpliTaq Gold, PE Applied Biosystems) in 1.56 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM of each dNTP and 10 nmol of each primer. The cycling conditions were 95°C initially for 7 min followed by 40 cycles of 95°C, 55°C and 72°C of 30 s each, then a final extension of 30 min at 72°C. The fluorescent PCR products were assayed by capillary electrophoresis and visually analysed using the ABI 3730 DNA Analyser (Applied Biosystems) with GeneScan Analysis software. Allele lengths were confirmed by DNA sequencing of homozygous alleles.

Table I.

Primers used for qRT–PCR and microsatellite genotyping

| Gene or locus | Genebank accession number | Location of amplicon | Forward primer (5′–3′) | Reverse primer (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18S | AF176811 | 56–146 | AGAAACGGCTACCACATCCAA | CCTGTATTGTTATTTTTCGTCACTACC |

| FBN1 | BC146854 | 1822-1882 | AGCACACTCACGCGGACA | AGATCCGGCCATTCTGTAAACA |

| FBN2 | NM_001999 | 7545-7646 | TCCAGTCAAGTTCTTCAGGCAC | TGCGACTACTGGATGCCATTT |

| FBN3 | NM_032447 | 1716-1787 | TGGCGGCCACTACTGCAT | TTGGTACAGTGGCCGTTCAC |

| LTBP-1 | BC130289 | 3195-3322 | CCCCAATGTCACGAAACAAGA | AACCTTTCCCTTTGGGACACA |

| LTBP-2 | NM_000428 | 3276-3382 | CAGGAAAGGACACTGCCAAGA | CCTCACAGGCCAGACAAGTGTA |

| D19S884 | NC_000019 | 62 185–62 353 | GGAGTTGCTCAGGGTC | TCCCTCAACCCCCCGAGTTC |

Statistical analyses

LD analyses and pairwise LD plots of D′ were generated using the Haploview 3.32 software (http://www.broad.mit.edu/haploview/haploview) (Barrett et al., 2005). The statistical power to detect an association in our case–control cohort was calculated by post-hoc tests implemented in the G.Power software (Buchner et al., 1997) for an alpha (P-value) of 0.05 over effect sizes ranging from 0.1 (small) to 0.5 (medium). The sample has 60% power to detect an effect size of 0.2 and greater than 88% power for effect sizes of 0.3 or more. Case–control association tests for SNP markers were performed using unphased 3.0.10 (Dudbridge, 2008). Odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated using Woolf's formula with Haldane's correction. P-values were corrected for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni's correction. Case–control association tests for the microsatellite marker D19S884 were performed using Clump 2.3 (www.mds.qmw.ac.uk/statgen/dcurtis/software.html) and Fisher's exact test. P-values for Fisher's exact tests were calculated using GraphPad Prism 5.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego California USA, www.graphpad.com) and were Bonferroni corrected for multiple comparisons.

Tissues for gene expression analyses

Collection of tissues for gene expression analyses was approved by the Institution Review Boards of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, USA, St Georges University of London, England and The University of Adelaide, Australia. Informed written consent was obtained prior to collection of tissues. Tissues were obtained from premenopausal women undergoing procedures for benign gynaecologic conditions. PCOS ovarian phenotype was diagnosed based on the presence of three or more of the following criteria: enlarged ovarian volume (>9 ml), 10 or more follicles of 2–8 mm in diameter, increased density and volume of stroma or a thickened tunica (Mason et al., 1994). Specimens were obtained from ovarian stroma/cortex (n = 9 non-PCO and 4 PCO ovarian phenotype), ovarian follicles (n = 3, >8 mm diameter) and corpora lutea (n = 3). The human ovarian cancer cell lines OVCAR-3, OVCAR-5 and SKOV-3 (ascites derived) originating from ovarian adenocarcinomas were obtained from the ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA) and the granulosa tumour cell line KGN (Nishi et al., 2001) was obtained with consent from its originators Professors Hajime Nawata and Toshihiko Yanase of Kyushu University and Professor Yoshihiro Nishi of Kurume University. Tissues and cells were either stored in RNAlater (Ambion, Inc., Austin, TX) at −20°C, or snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C prior to RNA or protein isolation.

Gene expression analyses

Total RNA was isolated from ∼100 mg wet weight of stored stromal tissue using 1 ml of Trizol (Invitrogen Australia Pty. Ltd., Mt Waverley, VIC, Australia). Briefly, tissue was homogenized for approximately 30 s on ice using a polytron homogenizer before extraction was carried out as per manufacturer's instructions. Ten micrograms of total RNA was treated with 2 U of DNase I (Ambion Inc, Austin, TX, USA) and first-strand complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from the DNase-treated RNA (2.5 µg) using 200 U Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen Australia Pty. Ltd.) and 500 ng random hexamers (Geneworks, Thebarton, SA, Australia). Primers were designed against published mRNA sequences using Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems). Primer sequences for human FBN1, 2 and 3 and, LTBP-1 and -2 mRNA are shown in Table I. Real-time PCR amplification was performed using an ABI PRISM 7000 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems) by adding 2.5 µl of appropriately diluted cDNA, 10 µl 2× SYBR green master mix (Applied Biosystems), 7.1 µl water and 0.2 µl of 12.5 µM forward and reverse primers per well. Samples were amplified in duplicate for one cycle at 50°C for 2 min and 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min.

To generate a standard curve for each PCR assay, DNA standards for each target sequence were prepared by sub-cloning the PCR products of the corresponding target sequence into pCR2.1-TOPO vector (Invitrogen). The plasmid DNA was isolated and quantified using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Nanodrop technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). DNA sequences were verified by automated sequencing (3730 DNA analyser, Applied Biosystems). Concentrations were calculated from absorbance at 260 nm. Plasmid DNA was serially diluted over three logs to establish a standard curve in a range, determined for each sample, which bounded the CT values obtained for samples (between 1 ng/μl and 10 ag/μl). Concentration of each target was generated from the CT and standard curve and was normalized to the concentration of 18S ribosomal RNA in each sample (calculated by the CT and standard curve for 18S). Gene expression of target sequences was subsequently expressed as fmoles target sequence mRNA/nmole 18S ribosomal RNA. For each gene the expression levels were normally distributed and comparisons between each ovarian compartment and between PCO and non-PCO tissues were compared by ANOVA, with no post hoc tests necessary as no significant differences were found.

Results

SNP and microsatellite analyses

Marker selection

We successfully genotyped 173 PCOS patients and 194 healthy control subjects for 32 SNPs (Table II) within 82 kb of the FBN3 gene region (gene map in Fig. 1). We included SNPs (n = 10) that result in non-synonymous amino acid changes in the FBN3 protein (Table II), with the intention of identifying PCOS-associated FBN3 mutations that might lead to defects in the functioning of the FBN3 protein either pre- or post-translationally. One SNP (rs17202741) showed no heterogeneity in the population and another (rs12972954) showed significant departures from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (possibly indicating a problem with the primers used for genotyping). Both were subsequently excluded from further analyses.

Table II.

Information on the SNPs examined, including chromosomal and gene location, sequence variation and the frequencies of their minor alleles for both control and PCOS patients, and the P-value for deviation of the genotype frequencies from the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium

| Public ida | Chromsomal locationb | Gene location | Variation# | Minor allele# | Hardy–Weinberg P-valuec | Allele frequencyd |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Case | ||||||

| rs2287937 | 8036420 | 3′ UTR | G/C | G | 1.00 | 0.19 | 0.23 |

| †rs12972954 | 8037849 | Intronic | C/T | T | – | – | – |

| rs10424096 | 8041170 | Intronic | A/G | G | 0.36 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| rs17261710 | 8042398 | Intronic | C/T | C | 0.67 | 0.17 | 0.18 |

| rs2303169 | 8052114 | Intronic | G/A | A | 0.06 | 0.44 | 0.47 |

| rs17160147 | 8054042 | Intronic | G/C | C | 0.17 | 0.70 | 0.71 |

| ††rs17202741 | 8062366 | Coding | A/C | C | – | – | – |

| AUG(M), CUG(L) | |||||||

| rs12151028 | 8064924 | Intronic | G/C | C | 0.06 | 0.86 | 0.88 |

| rs7245429 | 8065362 | Coding | C/A | A | 0.57 | 0.40 | 0.42 |

| CCT(P), CAT(H) | |||||||

| rs7245552 | 8065409 | Silent | C/A | C | 0.89 | 0.64 | 0.64 |

| CCC(P), CCA(P) | |||||||

| rs12608849 | 8066334 | Coding | T/C | T | 0.76 | 0.25 | 0.28 |

| TTC(F), ATC(I) | |||||||

| rs12150963 | 8066897 | Coding | G/C | G | 0.07 | 0.86 | 0.87 |

| AAC(N), AAG(K) | |||||||

| rs3829817 | 8067450 | Coding | G/A | A | 0.71 | 0.75 | 0.77 |

| CGG(R), CAG(Q) | |||||||

| rs3865464 | 8074340 | Intronic | C/T | T | 0.68 | 0.88 | 0.90 |

| rs33967815 | 8074545 | Coding | G/A | A | 0.22 | 0.31 | 0.32 |

| GGC(G), AGC(S) | |||||||

| rs10445638 | 8079428 | Intronic | G/A | A | 0.84 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| rs3813779 | 8080650 | Intronic | C/T | T | 0.23 | 0.53 | 0.56 |

| rs8111335 | 8082361 | Intronic | T/C | T | 0.74 | 0.14 | 0.17 |

| rs12975322 | 8082640 | Coding | G/A | A | 0.36 | 0.75 | 0.78 |

| GTC(V), ATC(I) | |||||||

| rs4804063 | 8082945 | Coding | G/A | G | 0.41 | 0.81 | 0.83 |

| AGT(S), GGT(G) | |||||||

| rs2086149 | 8083620 | Intronic | A/G | A | 0.27 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| rs35579498 | 8089871 | Coding | C/T | T | 0.86 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| CGG(R), TGG(W) | |||||||

| rs4527136 | 8092519 | Intronic | C/T | T | 1.00 | 0.44 | 0.47 |

| rs35840170 | 8094812 | Coding | G/A | A | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.97 |

| GTC(V), ATC(I) | |||||||

| rs3813774 | 8102499 | Silent | C/T | T | 0.35 | 0.05 | 0.08 |

| TGC(C), TGT(C) | |||||||

| rs12974280 | 8102508 | Silent | C/G | G | 0.57 | 0.62 | 0.64 |

| TCC(S), TCG(S) | |||||||

| rs8112525 | 8107051 | Intronic | G/A | A | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.10 |

| rs2061776 | 8108373 | Intronic | A/G | A | 0.13 | 0.84 | 0.85 |

| rs7246376 | 8109328 | Coding | C/T | T | 0.42 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| CCC(P), CTC(L) | |||||||

| rs12162237 | 8113070 | Intronic | T/C | T | 0.77 | 0.44 | 0.48 |

| rs7252584 | 8113241 | Intronic | G/C | C | 0.64 | 0.15 | 0.20 |

| rs7256533 | 8113721 | Intronic | T/C | T | 1.00 | 0.54 | 0.56 |

aReference SNP cluster identification number.

bPosition of nucleotide on chromosome 19 in Build 35 of the human genome from UCSC (www.genome.ucsc.edu).

cP-value for deviation of genotype frequencies from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium.

dMinor allelic frequency calculated using Haploview software.

†SNP displaying significant departure from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium.

††Potential SNP found not to be allelic. # The bases listed are those used in our design of primers and may represent the complimentary bases as listed in the Public Id.

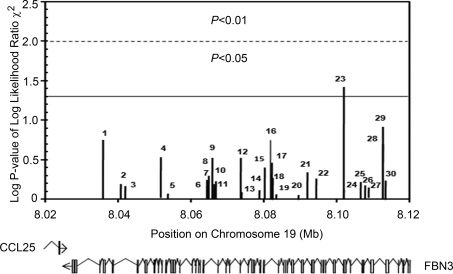

Figure 1.

Unphased association analysis for 30 SNPs all of which can be mapped within an 82 kb region spanning FBN3. Chromosomal position is plotted versus –log P-value for chi-square tests of association of each marker with PCOS. The dotted lines represent the cut-off mark for P-values reaching significance before Bonferroni's correction for multiple testing (P≤0.05 and P≤0.01). The position of introns and exons of the two genes (CCL25 and FBN3) relative to the SNPs analysed are displayed below the graph. Markers are 1 rs2287936, 2 rs10424096, 3 rs17261710, 4 rs2303169, 5 rs17160147, 6 rs12151028, 7 rs7245429, 8 rs7245552, 9 rs12608849, 10 rs12150963, 11 rs3829817, 12 rs3865464, 13 rs33967815, 14 rs10445638, 15 rs3813779, 16 rs8111335, 17 rs12975322, 18 rs4804063, 19 rs2086149, 20 rs35579498, 21 rs4527136, 22 rs35840170, 23 rs3813774, 24 rs12974280, 25 rs8112525, 26 rs2061776, 27 rs7246376, 28 rs12162237, 29 rs7252584 and 30 rs7256533.

SNP association analyses

The results of the Sequenom genotyping analysis are displayed in Table III. Relative frequencies for each allele of the 30 SNPs analysed from PCOS and control subjects are summarized. Most alleles showed almost identical population frequencies between PCOS and control subjects. SNP association analyses performed with unphased software (Dudbridge, 2008) found only one SNP (rs3813774) that achieved a significant (P = 0.04 uncorrected) association with PCOS (Fig. 1). In addition, case–control association analysis with Haploview software (Barrett et al., 2005) found one SNP (rs3813774) that achieved a significant (P = 0.04 uncorrected) association with PCOS (Table III). Upon correction for multiple comparisons, however, the P-value for this SNP no longer reached significance.

Table III.

Association analysis of SNPs within the FBN3 gene with PCOS showing chromosomal position, chi-square values, P-values, odds ratios, confidence limits and allelic frequencies for each SNP

| Marker ida | Chromosomal postionb | χ2 (Haploview)c | P-value (Haploview)d | −log P-value | Odds ratioe | 95% lowf | 95% highg | P-value corrected (Haploview)h | Minor allele |

Major allele |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case frequency | Control frequency | Case numberi | Control numberj | Case frequency | Control frequency | Case numberi | Control numberj | |||||||||

| rs2297936 | 8036420 | 1.81 (1.92) | 0.18 (0.17) | 0.74 | 1.28 | 0.89 | 1.83 | 1 (1) | 0.23 | 0.19 | 80 | 74 | 0.77 | 0.81 | 266 | 314 |

| rs10424096 | 8041170 | 0.21 (0.11) | 0.64 (0.74) | 0.19 | 1.15 | 0.64 | 2.04 | 1 (1) | 0.07 | 0.07 | 25 | 24 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 311 | 342 |

| rs17261710 | 8042398 | 0.17 (0.20) | 0.68 (0.66) | 0.17 | 0.92 | 0.63 | 1.35 | 1 (1) | 0.18 | 0.16 | 61 | 64 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 285 | 324 |

| rs2303169 | 8052114 | 1.08 (1.08) | 0.30 (0.30) | 0.52 | 0.86 | 0.63 | 1.17 | 1 (1) | 0.47 | 0.44 | 163 | 169 | 0.53 | 0.56 | 181 | 219 |

| rs17160147 | 8054042 | 0.03 (0.03) | 0.85 (0.85) | 0.07 | 1.03 | 0.74 | 1.43 | 1 (1) | 0.30 | 0.30 | 101 | 117 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 241 | 271 |

| rs12151028 | 8064924 | 0.32 (0.32) | 0.57 (0.57) | 0.24 | 1.13 | 0.72 | 1.77 | 1 (1) | 0.13 | 0.14 | 43 | 54 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 301 | 334 |

| rs7245429 | 8065362 | 0.41 (0.41) | 0.52 (0.52) | 0.28 | 0.91 | 0.67 | 1.22 | 1 (1) | 0.42 | 0.39 | 142 | 153 | 0.58 | 0.61 | 198 | 235 |

| rs7245552 | 8065409 | 0.002 (0.002) | 0.96 (0.96) | 0.02 | 0.99 | 0.73 | 1.35 | 1 (1) | 0.36 | 0.36 | 121 | 138 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 219 | 248 |

| rs12608849 | 8066334 | 1.05 (1.05) | 0.31 (0.31) | 0.51 | 1.19 | 0.86 | 1.64 | 1 (1) | 0.28 | 0.25 | 97 | 96 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 245 | 288 |

| rs12150963 | 8066897 | 0.21 (0.21) | 0.65 (0.65) | 0.19 | 0.90 | 0.58 | 1.42 | 1 (1) | 0.13 | 0.14 | 43 | 53 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 299 | 333 |

| rs3829817 | 8067450 | 0.26 (0.22) | 0.61 (0.64) | 0.21 | 1.09 | 0.78 | 1.54 | 1 (1) | 0.23 | 0.25 | 80 | 96 | 0.77 | 0.75 | 266 | 292 |

| rs3865464 | 8074340 | 1.08 (1.08) | 0.30 (0.30) | 0.52 | 0.78 | 0.50 | 1.23 | 1 (1) | 0.10 | 0.12 | 34 | 48 | 0.90 | 0.88 | 308 | 340 |

| rs33967815 | 8074545 | 0.03 (0.06) | 0.85 (0.81) | 0.07 | 1.03 | 0.76 | 1.40 | 1 (1) | 0.32 | 0.31 | 111 | 122 | 0.68 | 0.69 | 235 | 266 |

| rs10445638 | 8079428 | 0.07 (0.07) | 0.79 (0.79) | 0.10 | 0.93 | 0.55 | 1.57 | 1 (1) | 0.09 | 0.09 | 31 | 33 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 309 | 353 |

| rs3813779 | 8080650 | 0.68 (0.57) | 0.41 (45) | 0.39 | 0.88 | 0.67 | 1.18 | 1 (1) | 0.44 | 0.47 | 150 | 181 | 0.56 | 0.53 | 194 | 207 |

| rs8111335 | 8082361 | 1.80 (1.81) | 0.18 (0.18) | 0.74 | 1.32 | 0.86 | 2.02 | 1 (1) | 0.17 | 0.14 | 59 | 53 | 0.83 | 0.86 | 283 | 335 |

| rs12975322 | 8082640 | 0.88 (0.88) | 0.35 (0.35) | 0.46 | 1.18 | 0.83 | 1.67 | 1 (1) | 0.22 | 0.25 | 75 | 96 | 0.78 | 0.75 | 269 | 292 |

| rs4804063 | 8082945 | 0.38 (0.38) | 0.54 (0.54) | 0.27 | 0.89 | 0.62 | 1.28 | 1 (1) | 0.17 | 0.19 | 59 | 73 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 285 | 313 |

| rs2086149 | 8083620 | 0.03 (0.05) | 0.87 (0.83) | 0.06 | 0.97 | 0.71 | 1.33 | 1 (1) | 0.30 | 0.30 | 104 | 114 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 240 | 270 |

| rs35579498 | 8089871 | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.89 (0.89) | 0.05 | 1.06 | 0.49 | 2.26 | 1 (1) | 0.04 | 0.04 | 14 | 15 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 328 | 371 |

| rs4527136 | 8092519 | 0.54 (0.54) | 0.46 (0.46) | 0.34 | 1.12 | 0.83 | 1.50 | 1 (1) | 0.46 | 0.44 | 159 | 169 | 0.54 | 0.56 | 183 | 217 |

| rs35840170 | 8094812 | 0.35 (0.35) | 0.55 (0.55) | 0.26 | 1.30 | 0.54 | 3.11 | 1 (1) | 0.03 | 0.03 | 9 | 13 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 333 | 371 |

| rs3813774 | 8102499 | 4.29 (4.36) | 0.04 (0.04) | 1.46 | 1.88 | 1.00 | 3.52 | 1 (1) | 0.08 | 0.05 | 29 | 18 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 317 | 370 |

| rs12974280 | 8102508 | 0.09 (0.09) | 0.76 (0.76) | 0.12 | 0.95 | 0.70 | 1.30 | 1 (1) | 0.37 | 0.38 | 125 | 146 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 217 | 242 |

| rs8112525 | 8107051 | 0.27 (0.29) | 0.61 (0.59) | 0.21 | 0.88 | 0.54 | 1.42 | 1 (1) | 0.10 | 0.09 | 33 | 33 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 309 | 353 |

| rs2061776 | 8108373 | 0.17 (0.17) | 0.68 (0.68) | 0.17 | 1.09 | 0.71 | 1.67 | 1 (1) | 0.15 | 0.16 | 50 | 61 | 0.85 | 0.84 | 290 | 325 |

| rs7246376 | 8109328 | 0.12 (0.12) | 0.73 (0.73) | 0.14 | 0.94 | 0.66 | 1.34 | 1 (1) | 0.20 | 0.21 | 67 | 80 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 275 | 308 |

| rs12162237 | 8113070 | 1.64 (1.64) | 0.20 (0.20) | 0.70 | 1.21 | 0.90 | 1.62 | 1 (1) | 0.48 | 0.44 | 166 | 168 | 0.52 | 0.56 | 178 | 218 |

| rs7252584 | 8113241 | 2.36 (2.36) | 0.12 (0.12) | 0.92 | 0.74 | 0.50 | 1.08 | 1 (1) | 0.20 | 0.15 | 67 | 59 | 0.80 | 0.85 | 273 | 325 |

| rs7256533 | 8113721 | 0.29 (0.29) | 0.59 (0.59) | 0.23 | 0.92 | 0.69 | 1.23 | 1 (1) | 0.44 | 0.46 | 150 | 178 | 0.56 | 0.54 | 190 | 208 |

aReference SNP cluster ID.

bPosition of nucleotide on chromosome 19 in Build 35 of the human genome from UCSC (www.genome.ucsc.edu).

cChi-squared values calculated using unphased 3.0.10 software.

dP-value of odds ratio.

eOdds ratios were calculated using unphased 3.0.10 software.

fLower bound on the 95% confidence interval for the odds ratio.

gUpper bound on the 95% confidence interval for the odds ratio.

hP-value corrected for multiple testing (Bonferroni correction).

iNumber of alleles in control subjects.

jNumber of alleles in case subjects.

Haplotype association and linkage analyses

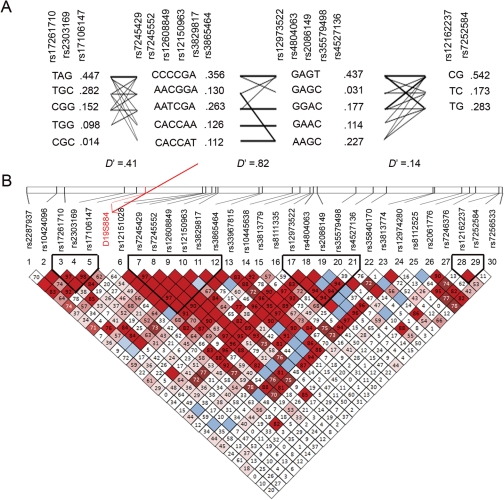

In order to increase the potential to identify a PCOS-associated SNP in the FBN3 genomic region we also performed LD haplotype association analyses using Haploview software (Barrett et al., 2005). Haplotype association analysis can increase power to detect a signal from other unknown SNPs (not in current databases) by performing the association test on haplotype groups rather than individual SNPs. Four haplotype blocks with 18 haplotypes were identified by Haploview using the method described by Gabriel et al. (2002) (Fig. 2a). Haplotype association frequencies, haplotype population frequencies and D′ scores of these haplotype blocks are shown in Fig. 2. Haplotype analysis failed to identify haplotypes that show significant association with PCOS. Given that the marker that led us to examine SNPs in FBN3 (the microsatellite D19S884) is located in a region of low LD (Fig. 2 and Urbanek et al., 2007), this result is perhaps not surprising as haplotype blocks do not by definition exist in regions of low LD.

Figure 2.

(A) Haplotypes predicted by Haploview. Four blocks were observed with the haplotpes of each block shown. Darker lines between haplotypes indicate a higher percentage of association with the linked haplotypes. Haplotype frequencies are indicated in red. D′ values for LD are indicated below each haplotype block. Chromosomal positions were taken from those reported for build 35 of the UCSC genome website (http://www.genome.ucsc.edu/). (B) Haploview generated graphic analysis of LD in an 82 kb region of chromosome 19 spanning FBN3. The relative position of each of the 31 markers (30 SNPs and D19S884, which is indicated with an arrow) on chromosome 19p13.2 is indicated by the vertical lines on the chromosomal map (top) and the proportion of LD (displayed as D′/LOD) is displayed below each marker. Haplotype blocks are indicated by dark lines. Strong LD (D′ = 1, LOD ≥ 2) is indicated by red, lighter shades pink indicate varying degrees of LD with lighter shades displaying less than darker (D′ < 1, LOD ≥ 2) and white indicates low LD (D′ < 1, LOD < 2).

Microsatellite D19S884 association analysis

As we were unable to demonstrate association between the SNPs that we typed in the FBN3 region and PCOS, we decided to genotype our patient–control cohort for the previously associated microsatellite marker D19S884. Microsatellite D19S884 allele frequencies for the study group are shown in Table IV. The numbers of CA repeats ranged from 14 to 24 in our cohort, and repeats of 22, 17, 18 and 20 were the most common at 26–27, 17, 12–13 and 11%, respectively. The frequencies of each allele reported here are similar to those published previously (Table IV).

Table IV.

For each allele in microsatellite D19S884 this table lists information on the sizes of the amplicons using either the current primers or those for amplimer AFMa299zc5, the numbers of CA repeats, the identification numbers ascribed to alleles by a previous study (Urbanek et al., 2005), the frequencies of each allele listed in Genbank and in a previous study (Villuendas et al., 2003) and that obtained in the current experiment, and the P-value for association of an allele with PCOS calculated using Fisher's exact test

| Amplicon sizes* |

Number of CA repeats | Allele identification number |

Allele frequency |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current data | Amplimer AFMa299zc5 | Urbanek et al. | Genbank | Genbank† | Data of Villuendas et al. |

Current data |

||||||||

| Controls | PCOS | Controls (number of alleles) | PCOS (number of alleles) | P-valuea | Odds ratio | 95% lowb | 95% highc | Corrected P-valued | ||||||

| 214 | 12 | – | 0.01 | |||||||||||

| 216 | 13 | 0.01 | – | |||||||||||

| 160 | 218 | 14 | A5 | 10 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.09 (33) | 0.06 (21) | 0.26 | 1.44 | 1.22 | 1.69 | 1.00 |

| 162 | 220 | 15 | A6 | 7 | 0.02 | – | 0.01 | 0.02 (6) | 0.01 (5) | 1.00 | 1.07 | 0.52 | 2.22 | 1.00 |

| 164 | 222 | 16 | A7 | 2 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.10 (38) | 0.12 (40) | 0.47 | 0.83 | 0.74 | 0.93 | 1.00 |

| 166 | 224 | 17 | A8 | 4 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.17 (64) | 0.17 (60) | 0.77 | 0.94 | 0.87 | 1.02 | 1.00 |

| 168 | 226 | 18 | A9 | 1 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.12 (46) | 0.13 (44) | 0.74 | 0.92 | 0.84 | 1.02 | 1.00 |

| 170 | 228 | 19 | A10 | 9 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.06 (22) | 0.03 (9) | 0.04 | 2.25 | 1.64 | 3.09 | 0.52 |

| 172 | 230 | 20 | A11 | 3 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.11 (42) | 0.11 (42) | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.88 | 1.10 | 1.00 |

| 174 | 232 | 21 | A12 | 6 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.05 (18) | 0.06 (20) | 0.51 | 0.79 | 0.64 | 0.99 | 1.00 |

| 176 | 234 | 22 | A13 | 5 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.26 (99) | 0.27 (94) | 0.62 | 0.92 | 0.87 | 0.97 | 1.00 |

| 178 | 236 | 23 | A14 | 8 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.03 (13) | 0.01 (4) | 0.05 | 2.96 | 1.54 | 5.68 | 0.63 |

| 180 | 238 | 24 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 (4) | 0.03 (9) | 0.16 | 0.39 | 0.19 | 0.80 | 1.00 | |||

| 182 | 240 | 25 | <0.00 (1) | 0.00 (0) | 1.00 | – | – | – | 1.00 | |||||

*To detect microsatellite D19S884 we designed different primers (Table I) to that of amplimer AFMa299zc5 listed in Genbank, hence the current amplicons differ in size.

†Frequencies of alleles listed in Genbank are from 8 CEPH families composed of 56 individuals as described for the microsatellite polymorphism rs3222751 under reference submission ss4914553.

aP-value for association of a microsatellite allele with PCOS calculated by Fisher's exact test.

bLower bound on the 95% confidence interval for the odds ratio.

cUpper bound on the 95% confidence interval for the odds ratio.

dP-value corrected for multiple testing (Bonferroni correction).

Microsatellite allele association analyses were performed using Fisher's exact test and the Clump program. Fisher's exact test did not identify any alleles of D19S884 that were significantly associated with PCOS. Allele 10 (19 CA repeats) was the only allele that was significant (P = 0.04 uncorrected), however, upon correction for multiple testing this P-value no longer approached significance (P = 0.52) (Table IV). Clump analysis of D19S884 failed to identify association between any of the 11 alleles detected and PCOS (data not shown).

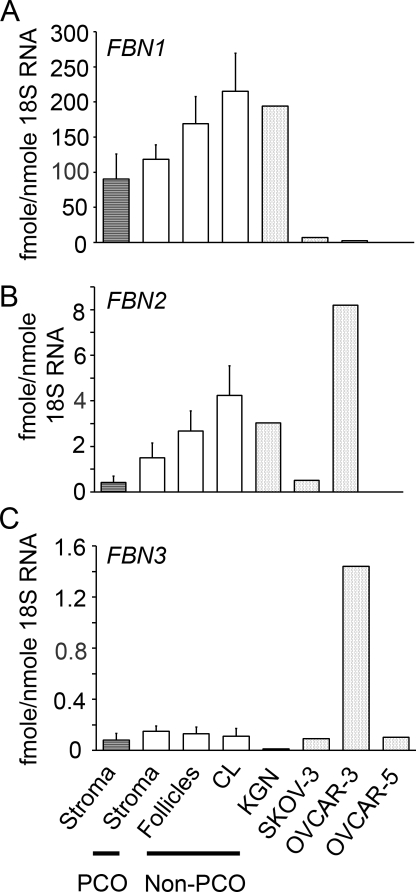

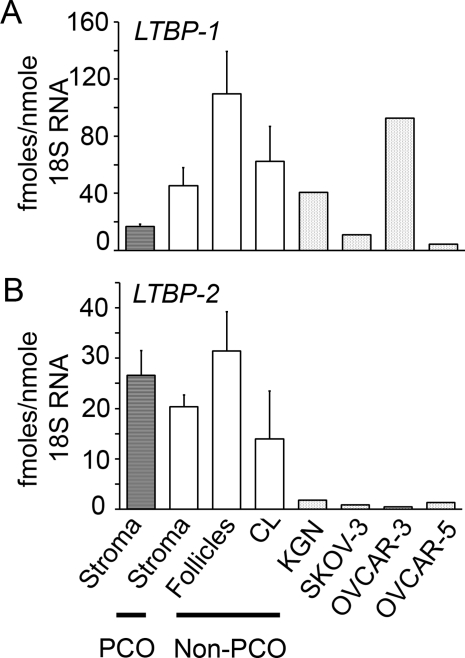

FBN and LTBP expression in human ovaries

We examined the expression of FBN1, 2 and 3 (Fig. 3), and LTBP-1 and -2 mRNA (Fig. 4) in normal human ovarian tissues including stroma/cortex (n = 9 non-PCO and 4 PCO ovarian phenotype), follicles (n = 3) and corpora lutea (n = 3) and ovarian cell lines. Expression levels for each gene were not significantly different between stroma, follicles and corpora lutea. FBN1 mRNA levels were 50–100 times greater than FBN2 and 200–1000-fold higher than FBN3 (Fig. 3). The granulosa tumour cell line KGN displayed similar levels of FBN1 and 2 but lower levels of FBN3 expression when compared with normal ovarian tissue samples (Fig. 3). OVCAR-3, OVCAR-5 and SKOV-3 had lower levels of FBN1 than normal ovarian tissues and KGN cells (Fig. 3). OVCAR-3 cells had very high levels of expression of both FBN2 and 3 expression compared with the other cell lines and the ovarian tissues (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Expression of FBN1 (A), FBN2 (B) and FBN3 (C) mRNA in human ovarian tissues and from the human ovarian tumour cell lines KGN, OVCAR-3, OVCAR-5 and SKOV-3. Data are presented as the mean values ± SEM expressed as fmoles RNA/nmole 18S ribosomal RNA, n = 4, 9, 3 and 3 for the PCO stroma/cortex and non-PCO stroma/cortex, follicles and corpora lutea (CL), respectively.

Figure 4.

Expression of LTBP-1 (A) and LTBP-2 (B) mRNA in human ovarian tissues and from the human ovarian tumour cell lines KGN, OVCAR-3, OVCAR-5 and SKOV-3. Data are presented as the mean values ± SEM expressed as fmoles RNA/nmole 18S ribosomal RNA, n = 4, 9, 3 and 3 for the PCO stroma/cortex and non-PCO stroma/cortex, follicles and corpora lutea (CL), respectively.

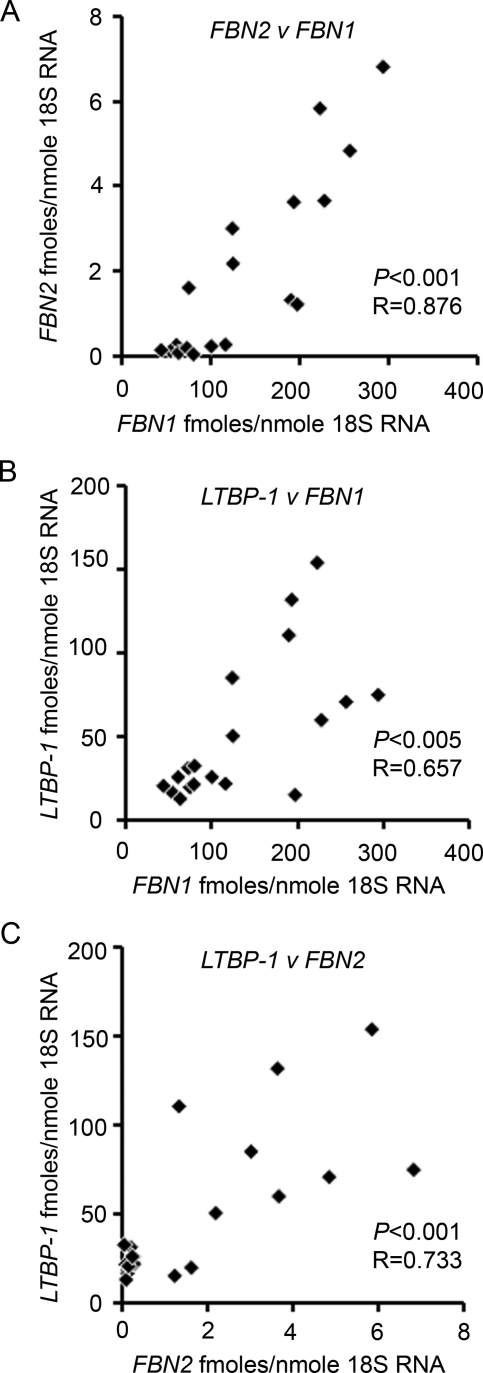

LTBP-1 expression levels were >3-fold greater than LTBP-2 in normal ovarian tissues (Fig. 4). OVCAR-3, OVCAR-5 and SKOV-3 had lower levels of LTBP-2 than normal ovarian tissues, but LTBP-1 expression was variable across the cell lines; with OVCAR-3 having the highest levels of expression (Fig. 4). Correlation analyses were conducted and FBN1 expression significantly correlated with FBN2 (P < 0.001) and LTBP-1 (P < 0.01) and FBN2 with LTBP-1 (P < 0.001) across all tissues (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Scatter plots of (A) FBN2 versus FBN1, (B) LTBP-1 versus FBN1 and (C) LTBP-1 versus FBN2 mRNA expression (fmoles/nmole 18S ribosomal RNA) using human ovarian tissues (excluding cell lines; n = 19). The P-values and correlation coefficient (R) relate to correlation with a Pearson's two-tailed test.

Discussion

We have conducted a case–control study of PCOS examining the genotypes of 30 SNPs, including 10 functional SNPs, in an 82 kb region of chromosome 19 flanking FBN3. In our cohort, we also genotyped the microsatellite marker D19S884, previously reported to be associated with PCOS by familial linkage analyses and located within intron 55 of FBN3. In addition, we examined the expression of the three FBNs and two of the LTBPs (LTBP-1 and -2) in ovarian tissues. We conclude that if FBN3 is involved in the aetiology of PCOS then its role is not readily apparent from these studies.

Tagging SNPs were chosen to span an 82 kb region of the FBN3 gene, which flanks the previously associated microsatellite marker D19S884, such that ∼100% of SNP alleles with minor allele frequencies >5% in this region were captured with an r2 value of >0.8. Thus, we would have expected to have been able to identify any common SNP within this region of 19p13.2 that showed significant association with PCOS. None of the 30 SNPs we tested had allele frequencies that were significantly different between controls and PCOS patients once corrected for multiple testing.

Microsatellite D19S884 is located in a non-conserved intronic region that displays low levels of LD, thus it remains possible that a causal SNP is located within this region. The closest SNP markers to D19S884 (chromosomal position 8056140) that were analysed here were rs17160147 and rs1251028, which are located at 2098 bp 3′ and 8784 bp 5′ of D19S884, respectively. There is at least one other SNP (rs1246064) in this region that was not analysed, nor captured by our tagging SNPs, and is heterogeneous in the CEU population. It is, however, unlikely that this SNP is causal for PCOS as it does not result in changes to protein sequence and was not found to be associated with PCOS in another study (Urbanek et al., 2007). There are other SNPs in this region that are heterogeneous in either African (rs8102892, rs8112982), Asian (rs8105886, rs17160153) or both populations (rs17160151, rs12984611) but these are not heterogeneous in a European population and hence unlikely to be causal in an Australian population. As we did not find any SNP in the FBN3 gene region that showed any significant association with PCOS, we examined the association of the microsatellite marker D19S884 in our cohort. Previous studies identified allele 8 (17 CA di-nucleotide repeats) as segregating with PCOS (Tucci et al., 2001; Urbanek et al., 2007). However, we were unable to identify any allele of the microsatellite that showed any significant association with PCOS in our cohort, after correcting for multiple testing.

The results presented here would appear to be in disagreement with other studies that found strong association between D19S884 and PCOS (Tucci et al., 2001; Urbanek et al., 2007). Both studies were conducted on subjects recruited solely from the USA and who fulfilled the 1990 NIH criteria. One study (Tucci et al., 2001) was a case–control study whereas the other (Urbanek et al., 2007) was a family-based study. We also recruited subjects of Caucasian background from the Australian population who fulfilled the 1990 NIH criteria for a case–control study. It is possible but unlikely that there are differences in genetic background with regard to PCOS between the Australian population and that of the USA. While the number of subjects in our study is low, our power calculations suggest that we had enough power to detect mutations that have a moderate (0.3) effect size and our numbers are much higher (173/194 PCOS/control subjects) than two previous case–control studies (Tucci et al., 2001; Villuendas et al., 2003) having 85/87 and 108/66 PCOS/control subjects, respectively. Our study is therefore more likely to be reflective of population allele frequencies and less prone to sampling bias. Despite this, it is possible that our numbers were too low to detect association of D19S884 with PCOS in the Australian population.

The expression of FBN1, 2 and 3 and LTBP-1 and -2 were examined in PCO ovarian stroma/cortex and non-PCO stroma/cortex, follicles and corpora lutea and clear patterns emerged. Firstly, there were no differences between stroma from ovaries with a PCO phenotype and those from non-PCO ovaries in any of the genes examined. In all the tissues examined, the expression of FBN1 was far greater than FBN2, which was far greater than FBN3, which was barely detectible. A similar pattern of expression was previously observed in bovine tunica and stroma of the cortex (Prodoehl et al., 2009). In our previous study, we found that in the bovine ovary, the expression of FBN1 within follicles was confined to the theca interna and in the tunica and stroma (corpora lutea were not examined) (Prodoehl et al., 2009). In the current study we found that the expression of LTBP-1 was greater than that of LTBP-2, which was also observed in the bovine tunica and stroma of the cortex (Prodoehl et al., 2009). In bovine ovaries, the expression of LTBP-1 was localized to the tunica and stroma of the cortex and in follicles in the inner area of the theca externa (Prodoehl et al., 2009). Additionally, the immunolocalization pattern of FBN1 and LTBP-1 were fibrillar in the tunica and stroma of the cortex and in the thecal layers, suggesting that they are both associated with microfibrils as has been observed previously (Isogai et al., 2003). Expression of FBN1 and 2 and LTBP-1 in the ovarian tissues examined here were correlated with each other. In bovine tunica and cortical stromal samples all three FBNs were correlated with LTBP-2 and not LTBP-1 (Prodoehl et al., 2009). This suggests that there is some degree of coordinate regulation amongst these genes in both humans and in the bovine.

To increase our knowledge of fibrillin family members in ovaries expression was also examined in human ovarian cancer cell lines OVCAR-3, OVCAR-5 and SKOV-3 (ascites derived) derived from ovarian adenocarcinoma, and in KGN cells which have a granulosa cell phenotype (Nishi et al., 2001). The expression levels of FBN1, 2 and 3 and LTBP-1 in the KGN cells was generally similar to that of the other ovarian tissues examined. The expression of these genes was much lower in the OVCAR-5 and SKOV-3 cells, in agreement with the localization of FBN1 and LTBP-1 and -2 in the bovine where no localization to the ovarian surface epithelium was observed (Prodoehl et al., 2009). However, OVCAR-3 had elevated levels of FBN2, 3, and LTBP-1 relative to normal ovarian tissues and other ovarian cancer cell lines.

It appears, from our genetic analysis, that the marker D19S884 and its associated gene, FBN3, have little or no impact on PCOS pathology in the Australian population. We cannot, however, rule out the possibility that other markers in the region of chromosome 19p13.2 are associated. Additionally our study of expression of five members of the fibrillin family in human ovaries found very low levels of FBN3, but our study also cannot rule out that alterations in FBN3 expression occur in other organs or tissues such as the anterior pituitary, influencing hormonal regulation of the ovary or adipose tissue. It is also possible that a genetic lesion in the FBN3 gene associated with PCOS pathology may cause functional changes in the protein's structure without affecting its expression levels. We conclude that if FBN3 is involved in the aetiology of PCOS then its role is not readily apparent from these studies.

Authors' Role

M.J.P., N.H., H.F.I.-R., M.A.G. and R.J.R. planned the experiments, conducted RT–PCR, microsatellite analyses, statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. Z.Z.Z., J.N.P. and G.W.M. conducted the SNP analysis and statistical analysis and assisted in writing the manuscript. T.E.H. and R.J.N. developed the cohort of PCOS and control patients, isolated the DNA from the lymphocytes from these patients, and reviewed the manuscript. W.E.R., B.R.C. and H.D.M. provided human ovarian samples and RNA and reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

Funding to support this research was obtained from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, University of Adelaide, the Clive and Vera Ramaciotti Foundation, the Wellcome Trust, and National Institute of Health, and Medical Research Council UK.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professors Hajime Nawata and Toshihiko Yanase of Kyushu University and Professor Yoshihiro Nishi of Kurume University for the KGN cell line, Drs Suman Rice and Laura Pellatt for ovarian tissues, and Dr Carmela Ricciardelli and Miranda Ween for the cancer cell lines. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

References

- Adams J, Polson DW, Franks S. Prevalence of polycystic ovaries in women with anovulation and idiopathic hirsutism. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;293:355–359. doi: 10.1136/bmj.293.6543.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato P, Simpson JL. The genetics of polycystic ovary syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;18:707–718. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balen AH, Conway GS, Kaltsas G, Techatrasak K, Manning PJ, West C, Jacobs HS. Polycystic ovary syndrome: the spectrum of the disorder in 1741 patients. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:2107–2111. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis visualization of LD haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boileau C, Jondeau G, Mizuguchi T, Matsumoto N. Molecular genetics of Marfan syndrome. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2005;20:194–200. doi: 10.1097/01.hco.0000162398.21972.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchner A, Faul F, Erdfeldera E. G Power: A Priori, Post-hoc, and Compromise Power Analyses for the Macintosh. University of Trier. 1997 (http://www.psychouni-duesseldorfde/app/projects/gpower. ) [Google Scholar]

- Carey AH, Waterworth D, Patel K, White D, Little J, Novelli P, Franks S, Williamson R. Polycystic ovaries and premature male pattern baldness are associated with one allele of the steroid metabolism gene CYP17. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:1873–1876. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.10.1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christner PJ, Ayitey S. Extracellular matrix containing mutated fibrillin-1 (Fbn1) down regulates Col1a1, Col1a2, Col3a1, Col5a1, and Col5a2 mRNA levels in Tsk/+ and Tsk/Tsk embryonic fibroblasts. Amino Acids. 2006;30:445–451. doi: 10.1007/s00726-005-0265-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway GS, Honour JW, Jacobs HS. Heterogeneity of the polycystic ovary syndrome: clinical, endocrine and ultrasound features in 556 patients. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1989;30:459–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1989.tb00446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corson GM, Charbonneau NL, Keene DR, Sakai LY. Differential expression of fibrillin-3 adds to microfibril variety in human and avian, but not rodent, connective tissues. Genomics. 2004;83:461–472. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2003.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Kouli CR, Bergiele AT, Filandra FA, Tsianateli TC, Spina GG, Zapanti ED, Bartzis MI. A survey of the polycystic ovary syndrome in the Greek island of Lesbos: hormonal and metabolic profile. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:4006–4011. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.11.6148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudbridge F. Likelihood-for nuclear families and unrelated subjects with missing genotype data. Hum Hered. 2008;66:87–98. doi: 10.1159/000119108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks S. Polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:853–861. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199509283331307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel SB, Schaffner SF, Nguyen H, Moore JM, Roy J, Blumenstiel B, Higgins J, DeFelice M, Lochner A, Faggart M, et al. The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science (New York, NY) 2002;296:2225–2229. doi: 10.1126/science.1069424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gharani N, Waterworth DM, Batty S, White D, Gilling-Smith C, Conway GS, McCarthy M, Franks S, Williamson R. Association of the steroid synthesis gene CYP11a with polycystic ovary syndrome and hyperandrogenism. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:397–402. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson MA, Hatzinikolas G, Davis EC, Baker E, Sutherland GR, Mecham RP. Bovine latent transforming growth factor beta 1-binding protein 2: molecular cloning, identification of tissue isoforms, and immunolocalization to elastin-associated microfibrils. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6932–6942. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.6932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giltay R, Kostka G, Timpl R. Sequence and expression of a novel member (LTBP-4) of the family of latent transforming growth factor-beta binding proteins. FEBS Lett. 1997;411:164–168. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00685-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glister C, Richards SL, Knight PG. Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMP) -4, -6, and -7 potently suppress basal and luteinizing hormone-induced androgen production by bovine theca interna cells in primary culture: could ovarian hyperandrogenic dysfunction be caused by a defect in thecal BMP signaling? Endocrinology. 2005;146:1883–1892. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glister C, Groome NP, Knight PG. Bovine follicle development is associated with divergent changes in activin-A, inhibin-A and follistatin and the relative abundance of different follistatin isoforms in follicular fluid. J Endocrinol. 2006;188:215–225. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govinden R, Bhoola KD. Genealogy expression cellular function of transforming growth factor-beta. Pharmacol Ther. 2003;98:257–265. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(03)00035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirani R, Hanssen E, Gibson MA. LTBP-2 specifically interacts with the amino-terminal region of fibrillin-1 competes with LTBP-1 for binding to this microfibrillar protein. Matrix Biol. 2007;26:213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughesdon PE. Morphology and morphogenesis of the Stein-Leventhal ovary and of so-called “hyperthecosis”. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1982;37:59–77. doi: 10.1097/00006254-198202000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isogai Z, Ono RN, Ushiro S, Keene DR, Chen Y, Mazzieri R, Charbonneau NL, Reinhardt DP, Rifkin DB, Sakai LY. Latent transforming growth factor beta-binding protein 1 interacts with fibrillin and is a microfibril-associated protein. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:2750–2757. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209256200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MR, Wilson SG, Mullin BH, Mead R, Watts GF, Stuckey BG. Polymorphism of the follistatin gene in polycystic ovary syndrome. Mol Hum Reprod. 2007;13:237–241. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gal120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanzaki T, Olofsson A, Moren A, Wernstedt C, Hellman U, Miyazono K, Claesson-Welsh L, Heldin CH. TGF-beta 1 binding protein: a component of the large latent complex of TGF-beta 1 with multiple repeat sequences. Cell. 1990;61:1051–1061. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90069-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kevenaar ME, Laven JS, Fong SL, Uitterlinden AG, de Jong FH, Themmen AP, Visser JA. A functional anti-mullerian hormone gene polymorphism is associated with follicle number and androgen levels in polycystic ovary syndrome patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:1310–1316. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kielty CM, Sherratt MJ, Shuttleworth CA. Elastic fibres. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:2817–2828. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.14.2817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knochenhauer ES, Key TJ, Kahsar-Miller M, Waggoner W, Boots LR, Azziz R. Prevalence of the polycystic ovary syndrome in unselected black and white women of the southeastern United States: a prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:3078–3082. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.9.5090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B, Godfrey M, Vitale E, Hori H, Mattei MG, Sarfarazi M, Tsipouras P, Ramirez F, Hollister DW. Linkage of Marfan syndrome and a phenotypically related disorder to two different fibrillin genes. Nature. 1991;352:330–334. doi: 10.1038/352330a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legro RS, Bentley-Lewis R, Driscoll D, Wang SC, Dunaif A. Insulin resistance in the sisters of women with polycystic ovary syndrome: association with hyperandrogenemia rather than menstrual irregularity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2128–2133. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.5.8513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason HD, Willis DS, Beard RW, Winston RM, Margara R, Franks S. Estradiol production by granulosa cells of normal and polycystic ovaries: relationship to menstrual cycle history and concentrations of gonadotropins and sex steroids in follicular fluid. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79:1355–1360. doi: 10.1210/jcem.79.5.7962330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner CR, Craig JE, Hussey ND, Norman RJ. No association between the -308 polymorphism in the tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNFalpha) promoter region and polycystic ovaries. Mol Hum Reprod. 1999;5:5–9. doi: 10.1093/molehr/5.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazono K, Olofsson A, Colosetti P, Heldin CH. A role of the latent TGF-beta 1-binding protein in the assembly and secretion of TGF-beta 1. Embo J. 1991;10:1091–1101. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb08049.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moren A, Olofsson A, Stenman G, Sahlin P, Kanzaki T, Claesson-Welsh L, ten Dijke P, Miyazono K, Heldin CH. Identification and characterization of LTBP-2, a novel latent transforming growth factor-beta-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:32469–32478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neptune ER, Frischmeyer PA, Arking DE, Myers L, Bunton TE, Gayraud B, Ramirez F, Sakai LY, Dietz HC. Dysregulation of TGF-beta activation contributes to pathogenesis in Marfan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2003;33:407–411. doi: 10.1038/ng1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi Y, Yanase T, Mu Y, Oba K, Ichino I, Saito M, Nomura M, Mukasa C, Okabe T, Goto K, et al. Establishment and characterization of a steroidogenic human granulosa-like tumor cell line, KGN, that expresses functional follicle-stimulating hormone receptor. Endocrinology. 2001;142:437–445. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.1.7862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prodoehl MJ, Irving-Rodgers HF, Bonner W, Sullivan TM, Micke GC, Gibson MA, Perry VE, Rodgers RJ. Fibrillins and latent TGFβ binding proteins in bovine ovaries of offspring following high or low protein diets during pregnancy of dams. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;307:133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez F, Pereira L. The fibrillins. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1999;31:255–259. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(98)00109-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai LY, Keene DR, Engvall E. Fibrillin, a new 350-kD glycoprotein, is a component of extracellular microfibrils. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:2499–2509. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.6.2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slowinska-Srzednicka J, Zgliczynski S, Wierzbicki M, Srzednicki M, Stopinska-Gluszak U, Zgliczynski W, Soszynski P, Chotkowska E, Bednarska M, Sadowski Z. The role of hyperinsulinemia in the development of lipid disturbances in nonobese and obese women with the polycystic ovary syndrome. J Endocrinol Invest. 1991;14:569–575. doi: 10.1007/BF03346870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbott E, Guzick D, Clerici A, Berga S, Detre K, Weimer K, Kuller L. Coronary heart disease risk factors in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:821–826. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.15.7.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson TB, Lerch TF, Cook RW, Woodruff TK, Jardetzky TS. The structure of the follistatin:activin complex reveals antagonism of both type I and type II receptor binding. Dev Cell. 2005;9:535–543. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucci S, Futterweit W, Concepcion ES, Greenberg DA, Villanueva R, Davies TF, Tomer Y. Evidence for association of polycystic ovary syndrome in caucasian women with a marker at the insulin receptor gene locus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:446–449. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.1.7274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanek M, Legro RS, Driscoll DA, Azziz R, Ehrmann DA, Norman RJ, Strauss JF, 3rd, Spielman RS, Dunaif A. Thirty-seven candidate genes for polycystic ovary syndrome: strongest evidence for linkage is with follistatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:8573–8578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanek M, Wu X, Vickery KR, Kao LC, Christenson LK, Schneyer A, Legro RS, Driscoll DA, Strauss JF, 3rd, Dunaif A, et al. Allelic variants of the follistatin gene in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:4455–4461. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.12.7026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanek M, Woodroffe A, Ewens KG, Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Legro RS, Strauss JF, 3rd, Dunaif A, Spielman RS. Candidate gene region for polycystic ovary syndrome on chromosome 19p13.2. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:6623–6629. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanek M, Sam S, Legro RS, Dunaif A. Identification of a polycystic ovary syndrome susceptibility variant in fibrillin-3 and association with a metabolic phenotype. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4191–4198. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verrecchia F, Mauviel A. TGF-beta and TNF-alpha: antagonistic cytokines controlling type I collagen gene expression. Cell Signal. 2004;16:873–880. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villuendas G, Escobar-Morreale HF, Tosi F, Sancho J, Moghetti P, San Millan JL. Association between the D19S884 marker at the insulin receptor gene locus and polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:219–220. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04570-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Chen Q, Simon TC, Strebeck F, Chaudhary L, Morrissey J, Liapis H, Klahr S, Hruska KA. Bone morphogenic protein-7 (BMP-7), a novel therapy for diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2003;63:2037–2049. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler DL, Church DM, Federhen S, Lash AE, Madden TL, Pontius JU, Schuler GD, Schriml LM, Sequeira E, Tatusova TA, et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:28–33. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild RA, Bartholomew MJ. The influence of body weight on lipoprotein lipids in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;159:423–427. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(88)80099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild RA, Painter PC, Coulson PB, Carruth KB, Ranney GB. Lipoprotein lipid concentrations and cardiovascular risk in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1985;61:946–951. doi: 10.1210/jcem-61-5-946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild RA, Alaupovic P, Parker IJ. Lipid and apolipoprotein abnormalities in hirsute women. I. The association with insulin resistance. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:1191–1196. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(11)90605-x. Discussion 1196–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yildiz BO, Yarali H, Oguz H, Bayraktar M. Glucose intolerance, insulin resistance, and hyperandrogenemia in first degree relatives of women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:2031–2036. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin W, Smiley E, Germiller J, Mecham RP, Florer JB, Wenstrup RJ, Bonadio J. Isolation of a novel latent transforming growth factor-beta binding protein gene (LTBP-3) J Biol Chem. 1995;270:10147–10160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.17.10147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zawadski JK, Dunaif A. Diagnostic criteria for polycystic ovary syndrome: towards a rational approach. In: Dunaif A, Givens JR, Haseltine FR, editors. Boston: Blackwell Scientific; 1992. pp. 377–384. [Google Scholar]

- Zeisberg M, Bottiglio C, Kumar N, Maeshima Y, Strutz F, Muller GA, Kalluri R. Bone morphogenic protein-7 inhibits progression of chronic renal fibrosis associated with two genetic mouse models. Am J Physiol. 2003;285:F1060–F1067. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00191.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao ZZ, Nyholt DR, Le L, Martin NG, James MR, Treloar SA, Montgomery GW. KRAS variation and risk of endometriosis. Mol Hum Reprod. 2006;12:671–676. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gal078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]