Abstract

The carbon isotopic composition of individual plant leaf waxes (a proxy for C3 vs. C4 vegetation) in a marine sediment core collected from beneath the plume of Sahara-derived dust in northwest Africa reveals three periods during the past 192,000 years when the central Sahara/Sahel contained C3 plants (likely trees), indicating substantially wetter conditions than at present. Our data suggest that variability in the strength of Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) is a main control on vegetation distribution in central North Africa, and we note expansions of C3 vegetation during the African Humid Period (early Holocene) and within Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 3 (≈50–45 ka) and MIS 5 (≈120–110 ka). The wet periods within MIS 3 and 5 coincide with major human migration events out of sub-Saharan Africa. Our results thus suggest that changes in AMOC influenced North African climate and, at times, contributed to amenable conditions in the central Sahara/Sahel, allowing humans to cross this otherwise inhospitable region.

Keywords: n-alkane carbon isotopes, vegetation, atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC)

The Sahara desert is known to have undergone major, and possibly abrupt, hydrological fluctuations and was vegetated at times in the past (1, 2). During a wet phase in the Early Holocene known as the African Humid Period (AHP), the region currently occupied by the Sahara desert was vegetated, contained forests, grasslands, and permanent lakes, and was occupied by human populations (2). When the AHP ended at ≈5.5 ka, the Sahara was transformed into a hyperarid desert (1). On orbital time scales, the large hydrological fluctuations in North Africa are linked to changes in the African monsoon, which is related to precession-forced variability in low-latitude summer insolation (1, 3). The abrupt transitions between humid and arid conditions observed in marine and terrestrial paleoclimate records from North Africa, however, cannot be explained solely by gradual orbital forcing (1); thus, other nonlinear feedback processes are required to explain the abrupt climate responses to orbital forcing. Vegetation and sea surface temperatures (SSTs) are two parameters that have often been cited as factors contributing to abrupt climate change in North Africa (3, 4). However, relatively little information exists regarding the type and extent of past vegetation in the Sahara/Sahel region, and at present, there are no paleoclimate records from below the summer dust plume (located between 0°N and 12°N and west of 10°W). Such records are critical for reconstructing past environmental conditions in North Africa, validating climate models, and assessing feedbacks between vegetation, orbital forcing, SSTs, and precipitation. Furthermore, human migration events have often been linked to climatic change (5), and the dynamic shifts that occurred in continental Africa between desert, grassland, and woodland environments likely have influenced hominin and faunal migration patterns.

Past Vegetation Shifts in the Central Sahara/Sahel Region

To better understand past vegetation changes in the Sahara/Sahel region, we studied marine sediment core GeoB9528-3 (09°09.96′N, 17°39.81′W; 3,057-m water depth) retrieved from the Guinea Plateau Margin, spanning the last 192 ka (SI Text and Fig. S1). This site receives dust from central North Africa near the boundary of the Sahara with the Sahel (Fig. 1 and SI Text), which is transported westward by the African Easterly Jet (AEJ), and thus serves as an excellent recorder of past vegetation changes in the central Sahara/Sahel region. We measured the carbon isotopic composition (δ13C) of long-chain n-alkanes with 29 (C29) and 31 (C31) carbon atoms (the two most abundant homologues) derived from plant leaf waxes, which are preserved in marine sediments and provide information on the relative contribution from C3 and C4 plants. The C3 photosynthetic pathway is the most common and is used by nearly all trees, cool-season grasses, and cool-season sedges, whereas C4 photosynthesis is used by warm-season grasses and sedges. African vegetation consists primarily of C4 grasses and C3 shrubs and trees (6, 7). In tropical Africa, aridity is recognized as the dominant control on the large-scale distribution of C3 versus C4 vegetation on longer time scales (4). C4 plants are enriched in δ13C compared with C3 plants; thus, past changes in African continental hydrology can be inferred from the n-alkane δ13C record (4). Our record shows substantial changes of >5‰ in both δ13C29 and δ13C31 over the last 192 kyr, suggesting large-scale changes in vegetation (Fig. 2). The δ13C of n-alkanes can be used to estimate the percentage of C4 vegetation contribution to each n-alkane based on binary mixing models that assume C29 end-member values of −34.7‰ (−35.2‰ for C31) and −21.4‰ (−21.7‰ for C31) for C3 and C4 vegetation, respectively (see SI Text and Tables S1 and S2). We note, however, that there is likely a considerable error associated with the absolute %C4 estimates (maximum error estimated at ± 20%; see SI Text) because of uncertainty in the end-member values. Nevertheless, these uncertainties do not affect interpretation of the general trends where relatively enriched (depleted) n-alkane δ13C values indicate increased (decreased) inputs from C4 plants. Thus, the overall trends in the n-alkane δ13C records provide important information on past vegetation shifts in central North Africa.

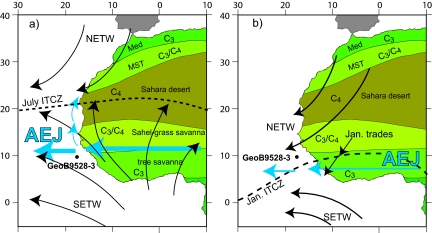

Fig. 1.

Location of gravity core GeoB9528-3 offshore Guinea and modern vegetation zones of Northwest Africa (34). From north to south the main vegetation zones are Mediterranean (MED) (C3 dominated), Mediterranean–Saharan transitional (MST) (mixed C3 and C4 plants), Sahara desert (C4 dominated), Sahel-grass savanna (mixed C3 and C4 plants), and tropical rainforest (C3 dominated). Three main wind systems influence the region of Northwest Africa, the Northeast trade winds (NETW), the Southeast trade winds (SETW), and the AEJ (also known as the Saharan Air Layer), and transport dust and plant leaf waxes from the African continent to the Atlantic. The NETW and the SETW converge at the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ; the meteorological equator). (A) During Northern Hemisphere summer, when the ITCZ is located at its most northerly position (surface expression at ≈20°N), the SETW are strongest and dust sourced in the Sahara and the Sahel is raised by easterly winds into the midaltitude flow (≈3 km) of the AEJ and transported beyond the continental margin between 10°N and 25°N. The AEJ is strongest during Northern Hemisphere summer when it is located at 10–12°N (36). (B) In Northern Hemisphere winter, the ITCZ migrates southwards (≈5°N) and the NETW are dominant. The AEJ is weaker in Northern Hemisphere winter and is located at ≈0–5°N (36). At this time, dust in the southern Sahara (the alluvial plains of Niger, Chad, and Faya Largeau) is uplifted by the low-altitude (500–1,500 m) NETW and deposited along wide areas off Africa between 2°N and 15°N (11), with the main axis of the dust plume located at ≈5°N. The Gulf of Guinea receives material sourced in the southern Sahara during Northern Hemisphere winter, which is transported over long distances and deposited offshore.

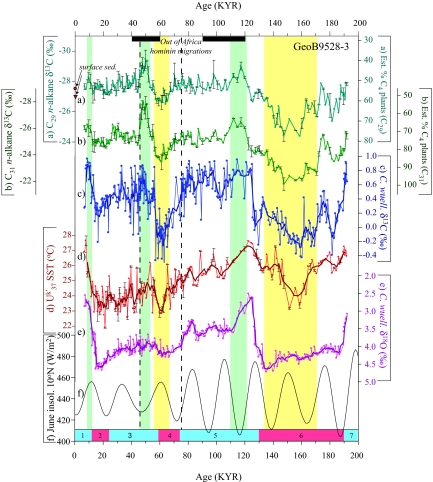

Fig. 2.

Geochemical records from GeoB9528-3. In traces c–e, the thick line represents the smoothed data (five-point running mean). In traces a, b, and d, the error bars represent the standard deviation of replicate analyses. All isotope data are reported in standard delta notation (‰) against the VPDB standard. The black bars at the top of the graph indicate documented human migrations out of Africa (23, 24). The vertical dashed lines indicate periods of major extinctions and turnovers of hominin populations at ≈75 and ≈45 ka (34). Wet intervals during the AHP, within MIS 3 and during MIS 5 are indicated by green shading. Arid intervals during MIS 6 and MIS 4 are indicated by yellow shading. The bar at the bottom indicates MIS 1–7. Trace a shows carbon isotope (δ13C) values of the C29 n-alkane. On the right side of the graph, the estimated %C4 plants is shown for the C29 n-alkane, based on a binary mixing model assuming end-member values of −34.7‰ and −21.4‰ for C3 and C4 vegetation, respectively. On the left side of the graph, δ13C values of C29 n-alkanes in surface sediments collected in the vicinity of GeoB9528-3 are shown. The red circle represents a δ13C value of −27.5‰ for site GIK16757-1 (8°58.60 N, 16°56.48 W) and the red triangle represents a δ13C value of −27‰ found at sites GIK16405-1 (12°25.37 N, 21°25.37 W) and GIK16408-2 (9°47.88 N, 21° 27.24W) (11). Trace b shows δ13C values of the C31 n-alkane. On the right side of the graph, the estimated %C4 plants is shown for the C31 n-alkane, based on a binary mixing model assuming end-member values of −35.2‰ and −21.7‰ C3 and C4 vegetation, respectively. Trace c shows the δ13C of the benthic foraminifer C. wuellerstorfi. The precision of these measurements is ± 0.05‰ based on replicates of an internal limestone standard. Trace d shows alkenone (U37k') SST reconstruction for GeoB9528-3 (see SI Text for methods). Trace e shows the δ18O of the benthic foraminifer C. wuellerstorfi. The precision of these measurements is ± 0.07‰ based on replicates of an internal limestone standard. Trace f shows June insolation at 10°N (14).

Plant leaf waxes (n-alkanes) can be transported to marine sediments by wind or water; however, fluvial transport is not likely at site GeoB9528-3 because the coring site is located offshore with no major rivers close by (SI Text). No major latitudinal shift of the wind belts occurred between the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) and the present (8); although wind strength varied in the past (8, 9), the direction of the AEJ remained constant (9) as did the geologic source terrane for terrigenous sediments to Northwest Africa (10). Thus, the direction of the AEJ likely remained constant during previous glacial and interglacial periods and the n-alkane record of GeoB9528-3 provides a continuous vegetation record of the Sahara/Sahel region. Furthermore, we note that the uppermost sample of GeoB9528-3 (≈7 ka) has a δ13C29 value of −27.6‰, which is in good agreement with surface sediments collected offshore Northwest Africa from 9–12°N latitude, which have δ13C29 values of −27‰ to −27.5‰ and are thought to be derived from dust from the Sahel/Sahara region (11).

During the past 200 ka, the n-alkane δ13C records of GeoB9528-3 indicate great variability with a contribution of 39–78% C4 plants to the C29 n-alkane and a contribution of 54- 99% C4 plants to the C31 n-alkane (Fig. 2). Our data show that for the majority of the past 192 ka, central North Africa was dominated by C4 vegetation, indicating arid conditions similar to or even more severe than at present (Fig. 2). However, several pronounced periods of increased contributions of C3 vegetation are observed in the early Holocene, within Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 3 (≈50–45 ka) and during MIS 5 (≈120–110 ka). The expansion of C3 plants during the early Holocene coincides with the African Humid Period (AHP) when the Sahara was vegetated (1, 2), supporting the idea that our record reflects vegetation in the Sahara/Sahel region. Remarkably, two intervals within MIS 5 and MIS 3 are characterized by even greater contributions of C3 vegetation compared with the AHP. The distribution of C3 and C4 vegetation in tropical Africa strongly depends on precipitation (4). Thus, the episodic expansions of C3 vegetation in our record likely reflect wetter conditions in the Sahel/Sahara region, whereas dominance of C4 plants, indicated by enriched n-alkane δ13C values, reflect arid conditions such as those of the present day. Although wet conditions during MIS 3 are not captured by grain size records from offshore Mauritania (12), this site is not situated directly under the path of the AEJ and likely does not capture the climate signal from further inland. In contrast, GeoB9528-3 is situated underneath the AEJ, and our n-alkane record also is a direct indicator of continental vegetation. Higher C4 contributions are noted throughout much of MIS 6 and during MIS 4, and at these times cooler U37k'-based SSTs are observed (Fig. 2), consistent with previous studies of tropical Africa that found increased abundances of C4 vegetation, and thus arid conditions, at times when cool SSTs were present in the tropical Atlantic (4). In comparison with the AHP, conditions were relatively more arid during the LGM, but LGM aridity was not nearly as severe as conditions during MIS 6 and MIS 4 (Fig. 2).

Causal Mechanisms for Vegetation Change and Hydrological Variability in Central North Africa

Several mechanisms can be invoked to explain the apparent episodic expansion (contraction) of C3 (C4) vegetation in the Sahara/Sahel region. Numerous studies have documented the influence of orbital forcing on North African climate and humid conditions during the AHP and MIS 5, which coincide with periods of maximum northern low-latitude summer insolation (1, 12, 13). However, the likely wettest intervals of our n-alkane δ13C records, at ≈120–110 and 50–45 ka, both coincide with relatively low values of summer insolation (14) and it is only during the AHP that maximum summer insolation and wet conditions are observed (Fig. 2).

For shorter, millennial-scale climate changes, several recent studies have shown that a reduction in the strength of Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC), which transports warm upper waters to the north and returns cold, deep water to the south) may trigger arid events in North Africa (12, 15). This process may also play a role in the observed longer-term vegetation changes. The proposed mechanism by which changes in AMOC control hydrological conditions in North Africa is related to the position of the monsoonal rain belt over the African continent. Weakening of AMOC, which can be triggered by freshwater input from the high latitudes (16, 17), leads to reduced deep-water formation rates in the North Atlantic (19). AMOC weakening also causes SST cooling in the North Atlantic region (16, 17) and is accompanied by a strengthening of the northeast trade winds (15, 17). Intensified trade winds, in combination with advection of cold air from the high latitudes, causes a southward shift of the North African monsoonal rain belt (15, 17), leading to drying in North Africa. It is hypothesized that intensification of the AEJ occurs in conjunction with a southward shift of the monsoonal rain belt, driven by the meridional temperature gradient between the Sahel and the cool Guinea coast, resulting in increased moisture transport from the African continent (15).

We examined the impact of AMOC on the distribution of C3 and C4 vegetation in the Sahara/Sahel region by comparing the n-alkane δ13C records to the δ13C of the benthic foraminifer Cibicidoides wuellerstorfi, hereafter referred to as δ13Cbenthic. Although 13C is a nutrient proxy, it is known that δ13C minima coincide with reductions in AMOC strength in the deep North Atlantic (19) and thus δ13Cbenthic primarily is a measure of the strength of AMOC and deep-water ventilation (18, 20). Throughout the past 200 ka, a remarkably close correlation is observed between δ13Cbenthic and the n-alkane δ13C records (Fig. 2, SI Text, and Fig. S2), indicating a strong connection between variability in AMOC strength and vegetation type in the Sahara/Sahel region. More enriched δ13Cbenthic values, suggesting increased AMOC strength and a relatively stronger influence of North Atlantic deep water (NADW) at the study location, correlate with expansions of C3 vegetation, whereas more depleted δ13Cbenthic values, suggesting a relatively weaker AMOC, correlate with expansions of C4 vegetation (Fig. 2). Links between the strength of AMOC and millennial scale arid events have been observed in a sedimentary record from offshore Mauritania (12), whereas slowdowns of AMOC are observed to trigger droughts in the Sahel during Heinrich events (15, 21). Interestingly, our data suggest that the strength of AMOC is a dominant influence on hydrological conditions in the Sahara/Sahel over longer time scales (Fig. 2). Maximum NADW formation is observed during stage 5d (20), which supports a link between overturning circulation and vegetation type in the Sahara/Sahel region, and may also explain why the greatest inputs of C3 vegetation do not coincide with summer insolation maxima.

Wet Conditions in the Central Sahara/Sahel and Hominin Migrations Out of Africa

The influence of AMOC on vegetation type in North Africa is of particular interest because this region may have played a key role in the dispersal of anatomically modern humans, which originated in sub-Saharan Africa at ≈195 ka (22), into Europe and Southwest Asia (23). A major dispersal period occurred between 130 and 100 ka (23, 24), which coincides with a major expansion of C3 vegetation from ≈120–110 ka (Fig. 2), and thus wetter conditions in the Sahara region, supporting the hypothesis that the Sahara could have provided a dispersal route out of Africa (24). Our interpretation is supported by other paleoclimate evidence and climate models suggesting a significant expansion of wetter conditions in the Sahara from 130 to 120 ka (24–28). When the S5 sapropel was deposited in the Mediterranean Sea (≈124–119 ka), fossil rivers in the Libyan and Chad basins of North Africa were active and provided northward drainage routes for precipitation delivered to central Saharan mountain ranges (28). In addition, recent evidence suggests that an uninterrupted freshwater corridor existed from the central Sahara to the Mediterranean from 130 to 117 ka (24).

The most depleted n-alkane δ13Cvalues of the entire record are noted within MIS 3, from ≈50–45 ka (Fig. 2), suggesting a major expansion of C3 plants. Interestingly, this interval coincides with a second major dispersal period of hominins out of Africa, dated to ≈60–40 ka, mainly based on studies of mtDNA (23, 29, 30). Additionally, mtDNA evidence suggests that a back migration into Africa from southwestern Asia occurred at ≈45–40 ka, and it is thought that this event resulted from a climatic change that allowed humans to enter the Levant (31). Thus, as with the first out of Africa migration during MIS 5, our data suggest that a second period of hominin migration at ≈60–40 ka may have been facilitated by amenable climate conditions in the central Sahara. This interpretation is supported by paleoclimate evidence suggesting that groundwater recharge occurred in the northern Sahara during MIS 3 (32) while a Ba/Ca record from the Gulf of Guinea displays increased values at ≈55 ka, suggesting less saline surface waters (33). Furthermore, in the Eastern Mediterranean Levant region there is evidence for extinctions and turnovers of hominin populations at ≈75 and ≈45 ka, and these events are hypothesized to be caused by shifts to cooler and more arid conditions (34). The n-alkane δ13C records indeed provide strong evidence for shifts to relatively more arid conditions, indicated by expansions of C4 vegetation, initiating at ≈75 and ≈45 ka, suggesting that similar climate patterns prevailed in both the central Sahara and the Levant regions.

Overall, our results show that variability in the strength of AMOC played a key role in the evolution of climatic conditions in central North Africa during the last 200 ka. Amenable conditions in the central Sahara that were capable of supporting C3 vegetation existed only during discrete and relatively brief time intervals when enhanced AMOC may have triggered vegetation change, thereby playing a crucial role in driving hominin migrations.

Materials and Methods

Core GeoB9528-3 was sampled at 5-cm intervals for molecular isotopic analyses. Freeze-dried sediment samples were extracted with a DIONEX Accelerated Solvent Extractor (ASE 200) using a solvent mixture of 9:1 dichloromethane (DCM) to methanol (MeOH). After extraction, a known amount of the internal standard squalane was added and the extract was separated into apolar, ketone, and polar fractions via alumina pipette column chromatography using solvent mixtures of 9:1 (vol/vol) hexane/DCM, 1:1 (vol/vol) hexane/DCM, and 1:1 (vol:vol) DCM/MeOH, respectively. Compound-specific δ13C analyses were performed on the aliphatic fraction with an Agilent 6800 GC coupled to a ThermoFisher Delta V isotope ratio monitoring mass spectrometer. Isotope values were measured against calibrated external reference gas. The δ13C values for individual compounds are reported in the standard delta notation against the Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (VPDB) standard. A total of 81 of the 193 samples analyzed were run in duplicate or triplicate with a reproducibility of on average 0.24‰ for the C29 n-alkane and 0.18‰ for the C31 n-alkane. The average reproducibility of the squalane internal standard was 0.15‰ (n = 288). Methods describing the δ18O and δ13C analyses of C. wuellerstorfi can be found in ref. 15, and methods describing the U37k' SST analyses can be found in SI Text.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Marianne Baas, Jort Ossebaar, and Michiel Kienhuis for assistance with the organic geochemical and isotopic analyses; Monika Segl and Christina Kämmle for assistance with the foraminiferal isotope analyses; two anonymous reviewers for detailed comments that improved this manuscript; and members of the University of Bremen Geosciences Department and the Center for Marine Environmental Sciences for samples from GeoB9528-3. This work was supported by Netherlands Bremen Oceanography 2. E.S. and S.M. are supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Research Center/Excellence Cluster “The Ocean in the Earth System.”

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0905771106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.DeMenocal P, et al. Abrupt onset and termination of the African Humid Period: Rapid climate responses to gradual insolation forcing. Q Sci Rev. 2000;19:347–361. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuper R, Kröpelin S. Climate-controlled Holocene occupation in the Sahara: Motor of Africa's evolution. Science. 2006;313:803–807. doi: 10.1126/science.1130989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Claussen M, et al. Simulation of an abrupt change in Saharan vegetation in the mid-Holocene. Geophys Res Lett. 1999;26:2037–2040. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schefuß E, Schouten S, Jansen JHF, Sinninghe Damsté JS. African vegetation controlled by tropical sea surface temperatures in the mid-Pleistocene period. Nature. 2003;422:418–421. doi: 10.1038/nature01500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Behrensmeyer AK. Climate change and human evolution. Science. 2006;311:476–478. doi: 10.1126/science.1116051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lloyd J, et al. Contributions of woody and herbaceous vegetation to tropical savanna ecosystem productivity: A quasi-global estimate. Tree Physiol. 2008;28:451–468. doi: 10.1093/treephys/28.3.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Still CJ, Berry JA, Collatz GJ, DeFries RS. Global distribution of C3 and C4 vegetation: Carbon cycle implications. Global Biogeochem Cy. 2003;17:1006. doi: 10.1029/2001GB001807. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarnthein M, Tetzlaff G, Koopmann B, Wolter K, Pflaumann U. Glacial and interglacial wind regimes over the Eastern Subtropical Atlantic and Northwest Africa. Nature. 1981;293:193–196. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grousset FE, et al. Saharan wind regimes traced by the Sr-Nd isotopic composition of subtropical Atlantic sediments: Last Glacial maximum vs today. Q Sci Rev. 1998;17:395–409. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cole JM, Goldstein SL, deMenocal PB, Hemming SR, Grousset FE. Contrasting compositions of Saharan dust in the eastern Atlantic Ocean during the last deglaciation and African Humid Period. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2009;278:257–266. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang YS, Dupont L, Sarnthein M, Hayes JM, Eglinton G. Mapping of C4 plant input from North West Africa into North East Atlantic sediments. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2000;64:3505–3513. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tjallingii R, et al. Coherent high- and low-latitude control of the northwest African hydrological balance. Nat Geosci. 2008;1:670–675. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kutzbach JE, Street-Perrott FA. Milankovitch forcing of fluctuations in the level of tropical lakes from 18 to 0 Kyr BP. Nature. 1985;317:130–134. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berger A, Loutre MF. Insolation values for the climate of the last 10 million years. Q Sci Rev. 1991;10:297–317. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mulitza S, et al. Sahel megadroughts triggered by glacial slowdowns of Atlantic meridional overturning. Paleoceanography. 2008;23:PA4206-1–PA4206-11. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang P, et al. Oceanic link between abrupt changes in the North Atlantic Ocean and the African monsoon. Nat Geosci. 2008;1:444–448. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiang JCH, Cheng W, Bitz CM. Fast teleconnections to the tropical Atlantic sector from Atlantic thermohaline adjustment. Geophys Res Lett. 2008;35:L07704. doi: 10.1029/2008GL033292. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vidal L, et al. Evidence for changes in the North Atlantic deep water linked to meltwater surges during the Heinrich events. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 1997;146:13–27. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McManus JF, et al. Collapse and rapid resumption of Atlantic meridional circulation linked to deglacial climate changes. Nature. 2004;428:834–837. doi: 10.1038/nature02494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duplessy JC, Shackleton NJ. Response of global deep-water circulation to Earth's climatic change 135,000–107,000 years ago. Nature. 1985;316:500–507. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carto SL, Weaver AJ, Hetherington R, Lam Y, Wiebe E. Out of Africa and into an ice age: On the role of global climate change in the late Pleistocene migration of early modern humans out of Africa. J Hum Evol. 2009;56:139–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDougall I, Brown FH, Fleagle JG. Stratigraphic placement and age of modern humans from Kibish, Ethiopia. Nature. 2005;433:733–736. doi: 10.1038/nature03258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stringer C. Palaeoanthropology: Coasting out of Africa. Nature. 2000;405:24–27. doi: 10.1038/35011166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osborne AH, et al. A humid corridor across the Sahara for the migration of early modern humans out of Africa 120,000 years ago. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:16444–16447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804472105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.deNoblet N, Braconnot P, Joussaume S, Masson V. Sensitivity of simulated Asian and African summer monsoons to orbitally induced variations in insolation 126, 115, and 6 kBP. Clim Dyn. 1996;12:589–603. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Armitage SJ, et al. Multiple phases of north African humidity recorded in lacustrine sediments from the fazzan basin, Libyan sahara. Q Geochronol. 2007;2:181–186. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaven C, Hillairemarcel C, Petitmaire N. A Pleistocene lacustrine episode in Southeastern Libya. Nature. 1981;290:131–133. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rohling EJ, et al. African monsoon variability during the previous interglacial maximum. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2002;202:61–75. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mellars P. Going east: New genetic and archaeological perspectives on the modern human colonization of Eurasia. Science. 2006;313:796–800. doi: 10.1126/science.1128402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forster P, Torroni A, Renfrew C, Rohl A. Phylogenetic star contraction applied to Asian and Papuan mtDNA evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 2001;18:1864–1881. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olivieri A, et al. The mtDNA legacy of the Levantine early Upper Palaeolithic in Africa. Sciencem. 2006;314:1767–1770. doi: 10.1126/science.1135566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zuppi GM, Sacchi E. Hydrogeology as a climate recorder: Sahara-Sahel (North Africa) and the Po Plain (Northern Italy) Global Planet Change. 2004;40:79–91. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weldeab S, Lea DW, Schneider RR, Andersen N. 155,000 years of West African monsoon and ocean thermal evolution. Science. 2007;316:1303–1307. doi: 10.1126/science.1140461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shea JJ. Transitions or turnovers? Climatically forced extinctions of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals in the east Mediterranean Levant. Q Sci Rev. 2008;27:2253–2270. [Google Scholar]

- 35.White F. The Vegetation of Africa, A Descriptive Memoir to Accompany the UNESCO/AETFAT/UNSO Vegetation Map of Africa. Scientific, and Cultural Organization, Paris: United Nations Educational; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nicholson SE, Grist JP. The seasonal evolution of the atmospheric circulation over West Africa and equatorial Africa. J Clim. 2003;16:1013–1030. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.