I. Introduction

Legal socialization is the process through which individuals acquire attitudes and beliefs about the law, legal authorities, and legal institutions. This occurs through individuals' interactions, both personal and vicarious, with police, courts, and other legal actors. To date, most of what is known about legal socialization comes from studies of individual differences among adults in their perceived legitimacy of law and legal institutions1, and in their cynicism about the law and its underlying norms.2 This work shows that adults' attitudes about the legitimacy of law are directly tied to individuals' compliance with the law and cooperation with legal authorities.3 Despite the potential importance of the development of these attitudes about law and their connection to illegal behavior, previous research on legal socialization prior to adulthood (i.e., adolescence) is rare.

Although some writers have discussed the ways in which family members and adults in the community shape children's and adolescents' attitudes and beliefs about law-related matters,4 little is known about the ways in which adolescents' legal socialization is shaped by their actual contact with the legal system. In fact, only a very small number of studies have examined legal socialization prior to adulthood.5 These studies have examined children's perceptions of law and legal procedures,6 rights and a “just world,”7 and legal reasoning.8 These early studies generally have relied either on cross-sectional or experimental designs, often with general population samples of young adults. As such, they are generally silent on the developmental component of legal socialization, the role of socializing conditions, and processes that children experience in everyday life.

The process of legal socialization should be particularly salient during adolescence, since this is the developmental period during which individuals are beginning to form an adult-like understanding of society and its institutions,9 and when they venture outside the closed systems of family and schools to experience laws and rules in a variety of social contexts where rule enforcement is more integrated with the adult world. In childhood, their experiences are limited to interactions with a small circle of authorities, such as school officials or store security guards, whose power is real, but whose formal legal status is ambiguous. More typically, whatever exposure children have had to law has been vicarious through family, friends or neighbors. But in contrast to children, adolescents' experiences with these new social and legal contexts should have more powerful influences in shaping notions of fairness and the moral underpinnings of law. Studies forecast that these notions of the fairness and morality of legal rules developed during adolescence may influence subsequent behavior in interactions with legal authorities as adults.10

Accordingly, it is reasonable to expect that interactions with legal authorities during late childhood and into adolescence should influence the development of notions of law, rules, and agreements among members of society, including adolescents, as well as the legitimacy of authority to deal fairly with citizens who violate society's rules. 11 Moreover, as a developmental outcome via socialization processes,12 legal socialization is similar to, and intertwined with, many other unfolding changes (e.g., psychosocial maturity) that occur during this period as well as with potentially powerful experiences of adolescence. One would expect perceptions about the legitimacy of law to change considerably during this time period, reflecting an ongoing dynamic between experiences and attitudes across several social contexts. In short, similar to other developmental processes which tend to grow over time and vary throughout the population, legal socialization also should exhibit growth, development, or vacillation as experience grows.

However, contact with the police and courts are infrequent among adolescents, even those in high-risk neighborhoods.13 As a result, most subjects in general population samples have little experience in the juvenile or criminal justice systems, and thus have a limited experiential basis to inform their notions regarding the law. Accordingly, studies of legal socialization in community samples of adolescents offer limited contributions to our understanding of the ways in which attitudes about the law, legal authorities, and legal institutions develop as a result of actual contact with the legal system. To better examine legal socialization as a developmental process, it is necessary to study a sample of juvenile offenders over time. In short, because adolescents are likely to vary in their patterns of legal socialization, just as they do in other developmental domains, longitudinal studies are needed to map out the natural history of development in this socio-legal domain, especially during critical developmental periods for adolescents who have nontrivial experiences with the justice system.

This study advances our understanding of legal cynicism and legitimacy in several, ways. First, we focus on adolescents. With few exceptions,14 prior studies have examined these dimensions of law-related behavior among adults. 15 If legal socialization develops during adolescence, closer measurement of this domain during that critical period is necessary to accurately identify a developmental process within the changing context of adolescence. Second, this study is the first to examine legal socialization over time in a developmental framework showing the stability or change in these domains during a critical developmental transition from late adolescence to early adulthood. Third, we examine legal socialization among active offenders. Prior work on legitimacy and legal cynicism has analyzed data from general population or community samples, where active offenders often are under-sampled. To the extent that legal cynicism and legitimacy are implicated in compliance with the law and cooperation with legal actors, we might expect these developmental outcomes to be skewed for offenders. Until this study, there has been very little research on active offenders,16 and none longitudinally, that considers the developmental patterning of legal socialization.

Accordingly, we analyze data from a juvenile court sample of adolescent offenders charged with serious crimes. Using data from four waves of interviews over eighteen months, we analyze variation in the developmental trajectories of two specific dimensions of legal socialization: legal cynicism and legitimacy. We next identify factors that might relate to the different developmental trajectories. To the best of our knowledge, the current investigation provides the first set of data on the longitudinal, within-individual patterning of two aspects of legal socialization among adolescents, specifically serious youthful offenders, a particularly important theoretical and policy-relevant group.17

II. LEGAL SOCIALIZATION

Our conception of legal socialization is rooted in larger normative views of fairness, justice, punishment, and criminal responsibility.18 These concepts are often tied to the tension between whether people obey the law because they fear punishment, or whether they comply with legal rules because compliance is a social and moral obligation, and that the law serves an essential social purpose. 19 Tyler 20 has effectively applied this conceptualization into a theory of compliance and legitimacy that contains key elements of procedural and distributive forms of justice.21 Tyler's work22 refocuses the question of whether people should obey the law to why people obey the law.23 Thus, the question of legal socialization transcends normative concerns and becomes a matter of social science and the explanation of behavior.

The legitimation of the law is the central dynamic in this socialization process. Research on legitimacy and the law is premised upon three assumptions: (1) that people have views about the legitimacy of authorities; (2) that those views shape their behavior; and (3) that those views arise out of social interactions and experiences.

Research on children and adults has identified two dimensions of legal socialization that may shape or sustain adolescent criminal behavior: institutional legitimacy and cynicism about the legal system. Institutional legitimacy refers to feelings of obligation to defer to the rules and decisions associated with legal institutions and actors.24 Tyler defines legitimacy as “the property that a rule or an authority has when others feel obligated to defer voluntarily.”25 As do others, we focus on the internalization of the responsibility to follow principles of personal morality. Legitimacy, therefore, reflects a willingness to suspend personal considerations of self-interest and to ignore personal moral values because a person thinks that an authority/rule is entitled to determine appropriate behavior within a given situation or situations.26 It is assessed by measuring the degree to which people feel that they “ought to“ obey decisions made by legal authorities, even when those decisions are viewed as wrong or not in their interests. Studies typically find that adults express strong feelings of obligation to obey the law, the police, and the courts.27

The second component of legal socialization is legal cynicism about the law and its underlying norms.28 Legal cynicism reflects general values about the legitimacy of law and social norms. It is based upon work on anomie,29 but is modified to reflect subgroup norms concerning minority urban communities.30 According to Sampson and Bartusch, “[t]he common idea is the sense in which laws or rules are not considered binding in the existential, present lives of respondents … [legal cynicism] taps variation in respondents' ratification of acting in ways that are “outside” of law and social norms.”31 Instead, respondents feel that acting in ways that are outside the law and community norms of appropriate conduct is reasonable.

These two dimensions are particularly appropriate to consider when examining legal socialization among adolescents. These notions of legitimacy and cynicism are part of a broader developmental phenomenon of self-definition with regard to authority structures common to adolescence, and the resolution of autonomy-related issues, including those involving relationships with authority figures, is a central psychosocial task of this period.32 In addition, these aspects of legal socialization are potentially influential in the development of antisocial behavior.33 In this study, we focus on the patterns of change in legal socialization among a group of serious delinquents. In order to examine individual differences in legal socialization and their relation to antisocial behavior, we need a basic understanding of how attitudes toward the legal system develop more generally.

A. THE LONGITUDINAL PATTERNING OF LEGAL SOCIALIZATION

It is reasonable to suspect that these two components of legal socialization, legitimacy and legal cynicism, should vary over time, within individuals, especially during childhood and adolescence. This developmental perspective reflects earlier research showing that the antecedents of a positive orientation toward political, legal, and social authorities play an important role in shaping adolescent and adult antisocial behavior. 34 Moreover, it seems useful to have a comprehensive understanding of the way in which these processes unfold within an individual across development. This supposition regarding the presence and importance of this developmental change is also supported by extant research in two distinct areas related to the legal socialization literature.35

The first is the literature in deterrence, specifically regarding perceived sanction threats, i.e., an individual's perception of the likelihood of being caught for committing an offense. Several studies of individual sanction threat perceptions indicate variation over time,36 and even within short time periods. For example, Minor and Harry's analysis of 488 young adults followed in a two-wave panel at two three-month intervals indicated that perceptions of sanction risk were not stable over the three month time period.37 In fact, for four of the six offenses studied (cocaine use, drunk and disorderly conduct, cheating, and shoplifting), perceptions of risk decreased significantly over the six month interval. In a second study, Paternoster and colleagues studied the issue of perceptual stability in samples of high school and college students.38 They found little perceptual stability, even within a six-month time period.39 Finally, in a two-wave panel of college students, Paternoster et al. found that as involvement in petty theft and bad check writing increased over a one-year period, perceptions of sanction certainty for both behaviors decreased.40 The authors also found that a reduction in perceived certainty was significantly related to increased involvement in both offenses.41 Finally, they found that being formally sanctioned between the two waves was related to an increase in perceived certainty.42 Much like Minor and Harry, Paternoster and colleagues also concluded that sanction threat perceptions were relatively unstable over short time periods.43

The second strand of relevant research comes from the compliance literature. Tyler's research shows that legal socialization matters in adults because it is related to compliance with law (criminality across the range of severity) and cooperation with police and other legal tasks (jury service, helping the police catch criminals).44 However, most of these are cross-sectional studies that compare people of different ages, and thus do not assess change within persons over time. With few exceptions, these cross-sectional studies have focused largely on adult samples.45

B. PRIOR RESEARCH ON LEGAL SOCIALIZATION

Existing research, although not longitudinal, nonetheless has highlighted many important aspects of the relation between legal socialization and law-abiding behavior.46 For example, in 1998 Sampson and Bartusch advanced and examined a neighborhood-level perspective on racial differences in legal cynicism, dissatisfaction with police, and the tolerance of various forms of deviance using a cross-section of 8782 residents of 343 neighborhoods in Chicago.47 Their focus was specifically on whether and how the structural characteristics of neighborhoods explained variations in legal cynicism and other attitudes.48 With respect to legal cynicism, their analyses indicated that while African Americans reported a higher level of cynicism than did whites, controlling for concentrated disadvantage eliminated this race effect.49 Importantly however, it did not alter the pattern of other important individual-level predictors of legal cynicism including gender, socioeconomic status, age, marriage, and separation/divorce.50

Using a panel design, Tyler's 1990 Chicago-based study explored the predictors of compliance with the law, specifically how recent personal experiences with the police and courts, and views of the legitimacy of the police and courts affected compliance.51 Though there are a number of important findings in his study, two particular results from the between-individual, longitudinal analyses are worth mentioning. First, legitimacy had an independent influence on compliance, even after controlling for a number of important variables, including the individual's prior level of compliance.52 Second, using contact with legal authorities as an intervening variable, Tyler found that procedural justice influenced subsequent perceptions of legitimacy even after controlling for prior perceived legitimacy suggesting that perceived procedural fairness is an important antecedent of legitimacy.53 Fagan and Tyler replicated these findings with a general population sample in New York City.54 Their work broadened the earlier analysis to include specific appraisals of the performance of the police in addition to their procedural fairness.55

Three other studies have provided relevant data. Tyler, Casper, and Fisher used a sample of 628 individuals accused of felonies interviewed prior to and following adjudication of their cases.56 Results from this study indicated that procedural justice was the key factor shaping individuals' orientations to the law and legal authorities.57 The second study pieced together six cross-sections of the General Social Survey (1972-1977) to assess stability and change in social tolerance.58 These authors found that adult levels of social tolerance were related to both pre-adult and early adult attitudinal environments.59 In a third study, Fagan and Tyler examined the contributions of legitimacy and legal cynicism to self-reported delinquency in a community sample of 212 children and adolescents ages ten to sixteen from two adjacent but racially diverse inner-city neighborhoods.60 They showed that both legitimacy and legal cynicism predicted self-reported offending in the expected directions.61 They also showed that perceptions of procedural fairness and “respect” of legal actors—police, school disciplinary staff, and store security guards—predicted both dimensions of legal socialization.62

Although these studies are certainly important for shaping the landscape of the legal socialization literature, they are limited in several respects. First, because they are largely cross-sectional, they offer little understanding of how aspects of legal socialization change over time within persons. Unfortunately, there has been no such research.63 Without longitudinal studies, it is difficult to gain a clear picture of legal socialization as a developmental process. Second, with the exception of Tyler et al., most studies have used general population samples.64 This is an important consideration in interpreting this literature because contact with legal actors is infrequent among both adults and adolescents, and thus they have little personal and/or vicarious experiential basis to inform their notions about law.65 Samples of individuals involved in the criminal justice system can provide important evidence because of their policy-relevant status.66

III. CURRENT STUDY

We analyze data from a juvenile court sample of serious adolescent offenders in two cities. Four waves of data (baseline, six, twelve, and eighteen months post-baseline) are used to model and describe variation in the developmental trajectories of these two dimensions of legal socialization. In order to address these questions, we employ an advanced statistical methodology that allows us to investigate the developmental trajectories that may characterize both legitimacy and legal cynicism, a methodology that has never been applied in the legal socialization area.

A. DATA

All subjects were participants in the Pathways to Desistance study. The ideas behind this larger investigation can be found in Mulvey et al.,67 and more methodological details of the study can be found in Schubert et al.68 The sample consists of 1355 adjudicated adolescents between the ages of fourteen and eighteen in Philadelphia (n=701) and Phoenix (n=654). The youth were selected for potential enrollment after a review of court files revealed they had been adjudicated delinquent or found guilty of a serious offense (overwhelmingly felonies). In order to ensure a sample with meaningful heterogeneity in offending activity, the proportion of juvenile males with drug offenses was limited to 15% of the sample in both cities. This restriction did not apply to females or to youths transferred to the adult system. The sample is 86% male. Twenty percent of the sample is white, 41% African-American, and 34% Hispanic. The average age at baseline was 16.04 (range 14-18), the proportion of those having at least one arrest in the past year was 50.1%, and the average number of prior arrests in the past year was almost one (range 0-9).

Informed consent was obtained from the juveniles and their parents or guardians. Eligible youths who agreed to participate in the study, and whose parents provided consent, then completed a baseline interview. For youths in the juvenile system, this interview was generally conducted within seventy-five days of their adjudication hearing. For youths in the adult system, the baseline interview was generally conducted within ninety days of the decertification hearing in Philadelphia or of the adult arraignment hearing in Phoenix (there is no waive back provision to the juvenile system under Arizona law).69 Subjects were also interviewed at six-month intervals through the eighteen-month data collection point for a total of four repeated observations. Retention at each of the four follow-up points was either 92% or 93%, especially high for a serious juvenile offender sample—particularly one followed longitudinally.

1. Variables of Interest

Legal Cynicism

Following Sampson and Bartusch70 and Srole,71 our measure of legal cynicism is composed of five questions which asked respondents to rate the degree to which: (1) Laws are meant to be broken, (2) It is okay to do anything you want, (3) There are no right or wrong ways to make money, (4) If I have a fight with someone, it is no one else's business, and (5) A person has to live without thinking about the future. Response options included: (1) Strongly Disagree; (2) Somewhat Disagree; (3) Somewhat Agree; and (4) Strongly Agree. Higher values on this scale indicate higher levels of legal cynicism (range 1-4). Psychometric analyses of the scale at baseline indicated that it was reliable (alpha=.60; CFI=.99, RMSEA=.03).

Legitimacy

Our measure of legitimacy follows from the measure employed by Tyler, 72 Tyler and Huo, 73 and others. Specifically, respondents answered eleven questions including: (1) I have a great deal of respect for the police, (2) Overall, the police are honest, (3) I feel proud of the police, (4) I feel people should support the police, (5) The police should be allowed to hold a person suspected of a serious crime until they get enough evidence to charge them, (6) The police should be allowed to stop people on the street and require them to identify themselves, (7) The courts generally guarantee everyone a fair hearing (trial), (8) The basic rights of citizens are protected in the courts, (9) Many people convicted of crimes in the courts are actually innocent [Reverse Coded], (10) Overall, judges in the courts here are honest, and (11) Court decisions here are almost always fair. Response options included: (1) Strongly Disagree; (2) Somewhat Disagree; (3) Somewhat Agree; and (4) Strongly Agree. Again, higher values indicate higher levels of perceived legitimacy of the law (range 1-5.2). Psychometric analyses of the scale at wave one indicated that it was reliable (alpha=.80; CFI=.92, RMSEA=.07).

2. Methods

Trajectory-based models were fit to the data to examine the within-person variability across time on the legal socialization measures. A group-based approach, like the trajectory methodology, lends itself nicely to analyzing questions that are framed in terms of the shape of the developmental course of the outcome of interest.74 The trajectory methodology is based on finite mixture models, or theoretically, on the notion that more than one class of individuals underlies an observed population/distribution. Recognizing that there may be meaningful subgroups within a population that follow distinctive developmental trajectories, Nagin and Land developed a modeling strategy that makes no parametric assumptions with respect to the distribution of persistent unobserved heterogeneity in the population.75 Unlike other techniques, the semi-parametric mixed (SPM) poisson model assumes that the distribution of unobserved persistent heterogeneity is discrete rather than continuous, and thus the mixing distribution is viewed as multinomial (i.e., a categorical variable). Each category within the multinomial mixture can be viewed as a point of support, or grouping, for the distribution of individual heterogeneity. The model, then, estimates a separate point of support (or grouping) for as many distinct groups as can be identified in the data.76 In other words, the trajectory methodology takes individuals who resemble one another on the outcome of interest and assigns them to a particular group. Individuals in each respective group resemble one another more so than they do the individuals assigned to other groups. The groups, then, are mutually exclusive such that each individual can only be a member of one trajectory group.

It is important to remember that the trajectory groups approximate population differences in developmental trajectories. A higher number of points of support (groups) yields a discrete distribution that more closely approximates what may be a true continuous distribution.77 Further, because each individual has a non-zero probability of belonging to each of the various groups identified, s/he is assigned to the group to which s/he has the highest probability of belonging. This is a particularly important feature of this methodology because it allows researchers to assess the claims of extant developmental models that make predictions about different groups of offenders. This cannot be accomplished with approaches that treat unobserved heterogeneity in a continuous fashion. In short, the trajectory methodology is well-suited for research problems with a taxonomic dimension, the purpose of which is to chart distinctive developmental trajectories, and to understand what factors account for their distinctiveness.78

Because we are dealing with continuous psychometric, yet bounded data, the Censored Normal version of the SPM is appropriate here. To evaluate model fit we follow extant research and use the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). BIC, or the log-likelihood evaluated at the maximum likelihood estimate less one-half the number of parameters in the model times the log of the sample size,79 tends to favor more parsimonious models than likelihood ratio tests when used for model selection. Following previous research,80 we use an iterative procedure for identifying meaningful groups. The approach we take is to begin with a one-group model and continue along the modeling space to two, three, four, five, and six groups, until we maximize the BIC.81

The approach taken here is primarily descriptive. We are concerned with whether there are meaningful subgroups of adolescents showing different patterns of legal socialization, what the legal socialization trajectories look like, and what sorts of demographic variables distinguish individuals showing these different trajectories.82 It is important to note that because the groups are intended as an approximation of a more complex underlying reality, the objective is not to identify the “true” number of groups. Instead, the aim is to identify as simple a model as possible that displays the distinctive features of the population distribution of trajectories.83 All trajectory models were fit using the Proc Traj procedure in SAS.

Descriptive statistics for the legal socialization variables and correlations among those variables over time may be found in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. As shown in Table 1, with regard to legal cynicism, the average value and the variation around that average (i.e., standard deviation) does not change much over time; however, there is some more change about both the mean and variation in legitimacy over time.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Baseline Mean (SD) |

6 Months Mean (SD) |

12 Months Mean (SD) |

18 Months Mean (SD) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legitimacy | 2.35(0.61) | 2.33(0.61) | 2.39(0.62) | 2.44(0.65) |

| Legal Cynicism | 2.02(0.60) | 2.05(0.62) | 2.02(0.61) | 2.02(0.62) |

Table 2.

Correlation Matrix of Legal Cynicism and Legitimacy Over Eighteen Months

| Legit T1 |

Legit T2 |

Legit T3 |

Legit T4 |

Cynic T1 |

Cynic T2 |

Cynic T3 |

Cynic T4 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legit T1 | 1 | |||||||

| Legit T2 | 0.528 | 1 | ||||||

| Legit T3 | 0.505 | 0.559 | 1 | |||||

| Legit T4 | 0.418 | 0.468 | 0.553 | 1 | ||||

| Cynic T1 | −0.173 | −0.173 | −0.176 | −0.125 | 1 | |||

| Cynic T2 | −0.187 | −0.222 | −0.233 | −0.242 | 0.462 | 1 | ||

| Cynic T3 | −0.16 | −0.228 | −0.252 | −0.301 | 0.413 | 0.534 | 1 | |

| Cynic T4 | −0.133 | −0.17 | −0.212 | −0.266 | 0.392 | 0.491 | 0.549 | 1 |

Note: All correlations significant at p<.05.

B. RESULTS

1. Legal Cynicism Trajectories

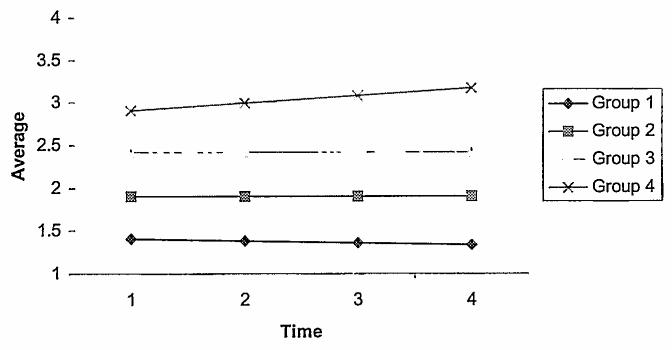

The best fitting model (i.e., maximization of the BIC statistic) for the legal cynicism data was a four-group model. Figure 1 shows the trajectories of expected (i.e., predicted on the basis of estimated model parameters) cynicism scores for each latent class implied by the model.

Figure 1.

Predicted Legal Cynicism Trajectories

Two findings immediately stand out in Figure 1. First, there are mean-level differences at the intercept (baseline) for all four groups. For example, at baseline, group 1 averages 1.40 (less cynical) on the cynicism scale while group 4 averages close to 3.0 (more cynical). Second, with the exception of group 4 (which includes 4.2% of the sample), groups 1 (17.9% of the sample), 2 (43.8% of the sample), and 3 (34.1% of the sample) exhibit flat and stable levels of cynicism across the eighteen-month time period. Group 4 exhibits some increasing cynicism between T1 and T4. In short, for the majority of the study participants, there is very little change in perceptions of legal cynicism over the time frame captured here.

For each study participant (and subsequent latent class) we computed the maximum posterior membership probabilities, the results of which may be found in Table 3. Specifically, we follow the model's ability to sort individuals into the trajectory group to which they have the highest probability of belonging (the ‘maximum probability’ procedure). Based on the model coefficient estimates, the probability of observing each individual's longitudinal pattern of legal cynicism is computed conditional on their being, respectively, in each of the latent classes. The individual is then assigned to the group to which they have the highest probability of belonging. This procedure, of course, does not guarantee perfect assignment, but higher posterior probabilities are indicative of more acceptable levels of class assignment.

Table 3.

Mean Posterior Probability Assignments—Legal Cynicism

| Group | Prob (G1) |

Prob (G2) |

Prob (G3) |

Prob (G4) |

25th Percentile |

75th Percentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (n=235) | 0.825 | 0.173 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.73 | 0.97 |

| 2 (n=608) | 0.078 | 0.783 | 0.137 | 0.000 | 0.68 | 0.89 |

| 3 (n=466) | 0.000 | 0.163 | 0.792 | 0.044 | 0.70 | 0.91 |

| 4 (n=46) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.199 | 0.800 | 0.63 | 0.96 |

Here, the mean assignment probabilities for each group are all quite high (all above .75) suggesting that the majority of individuals can be classified to a particular latent trajectory with high probability. For example, for group 1, the mean posterior probability was .825; for group 2, it was .783; for group 3, it was .792; and for group 4, it was .800.

2. What Factors Relate to Legal Cynicism?

In Table 4, we examined how the groups varied along a series of variables, several of which have been examined in the adult literature.84 We looked at: age (scored continuously, range 14-18), age-specific dummy variables (age 14 through age 18); site (1=Philadelphia, 2=Phoenix), the number of prior arrests in the past year (scored continuously, range 0-9), the age at first arrest (scored continuously, range 9-18), race-specific dummy variables (white, Hispanic, and African-American); gender (1=male, 2=female), whether the participant was locked-up at the baseline interview (1=yes, 0=no), and an adapted version of the Procedural Justice Inventory85 that focused on the adolescent's perception of fairness and equity connected with police and court processing.

Table 4.

Analysis of Variance—Legal Cynicism. Means Presented By Group.

| Variables | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | F-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | 1.446 | 1.468 | 1.530 | 1.369 | 2.751* |

| Priors past yr. | 0.78 | 0.88 | 1.12 | 0.91 | 4.784* |

| Age at first | 14.485 | 14.514 | 14.384 | 14.152 | 1.097 |

| Black | 0.459 | 0.403 | 0.405 | 0.434 | 0.843 |

| White | 0.255 | 0.236 | 0.137 | 0.130 | 7.520* |

| Hispanic | 0.246 | 0.312 | 0.401 | 0.413 | 6.758* |

| Gender | 1.22 | 1.16 | 1.08 | 1.02 | 12.602* |

| Locked-up | 0.327 | 0.302 | 0.388 | 0.326 | 2.957* |

| Age | 15.978 | 16.049 | 16.055 | 16.173 | 0.476 |

| Age 14 | 0.148 | 0.115 | 0.111 | 0.108 | 0.790 |

| Age 15 | 0.187 | 0.187 | 0.195 | 0.130 | 0.386 |

| Age 16 | 0.293 | 0.314 | 0.296 | 0.304 | 0.183 |

| Age 17 | 0.276 | 0.299 | 0.319 | 0.391 | 1.024 |

| Age 18 | 0.093 | 0.083 | 0.077 | 0.065 | 0.249 |

| PJ-Police (Overall) | 2.867 | 2.762 | 2.732 | 2.641 | 4.632* |

| PJ-Court (Overall) | 3.325 | 3.322 | 3.209 | 3.108 | 3.357* |

| PJ-Police (Direct) | 2.894 | 2.807 | 2.785 | 2.705 | 2.569* |

| PJ-Police (Indirect) | 2.782 | 2.632 | 2.577 | 2.452 | 5.736* |

| PJ-Court (Direct) | 3.430 | 3.291 | 3.296 | 3.140 | 3.452* |

| PJ-Court (Indirect) | 3.365 | 3.254 | 3.221 | 3.142 | 2.957* |

Conceptually, procedural justice taps the experiential and affective basis for translating interactions with legal processes into perceptions and evaluations of the law and the legal actors who enforce it. Fair treatment allows people to attribute legitimacy to authorities and creates a set of obligations to conform to their norms. It communicates to participants directly, and vicariously to people in contact with other participants in legal interactions, that laws are both legitimate and moral. Fair treatment also may reduce feelings of anger that lead to rule breaking.86 It strengthens ties to the law, a pivotal antecedent of delinquency,87 while at the same time counteracting labeling processes that are marginalizing and stigmatizing.88 Tyler and several other studies report that fair treatment is positively related to law abiding behavior among both younger and older adults.89 In developmental terms, fair treatment strengthens ties and attachments to the laws and social norms, as well as group membership. Such procedural justice judgments are found to both shape reactions to personal experiences with legal authorities90 and to be important in assessments based upon the general activities of the police.91

Following the operationalizations found in prior research, the measures are designed to tap several dimensions of fair treatment: correctability, ethicality, representativeness, and consistency.92 The outcomes of this process include evaluations of law and its underlying norms: legitimacy and legal cynicism.93 Following prior research,94 we hypothesize that males, minorities, older adolescents, those with prior arrests and an earlier age at first arrest, those who were locked-up, and those who perceive lower procedural justice regarding the police and courts should hold more cynical attitudes.

The results from the ANOVA analyses indicate that the four groups differ across twelve variables: site, priors, white, Hispanic, gender, lock-up status, and all six procedural justice variables. Regarding site, there are slightly more Philadelphia participants in group 4 (high cynicism group), whereas there are more Phoenix participants especially in group three. As would be expected, those individuals in the two groups (groups 3 and 4) who have the highest cynicism values also have the largest number of prior arrests. Group 1, who had the lowest cynicism scores, had the lowest number of priors in the past year. There were more white participants in the two lowest cynicism groups (1 and 2), while there were more Hispanic participants in the two groups (groups 3 and 4) with the highest cynicism values over the eighteen-month period. Age was not significantly different across the four cynicism trajectories. Also, there were more females in the lowest legal cynicism groups (1 and 2) than in the higher cynicism groups. Finally, the groups differ along all six procedural justice dimensions at baseline. Across almost all comparisons shown in Table 4, the two lowest cynicism groups consistently report higher (i.e., more favorable) procedural justice perceptions, while the two highest cynicism groups consistently report lower (i.e., less favorable) procedural justice perceptions—and this is the case across all domains and for the general and specific scales.

The high level of stability over time in legal cynicism and diversity in levels over time suggests that inter-individual differences among study participants in their cynicism about the legal system likely were established before their first assessment in this study, perhaps as young as fifteen years of age. In other words, the groups derived from the trajectory analyses may indicate statistically meaningful cut-points for dividing the group on a continuous measure of cynicism that is stable across the different time points.

Next, we examine what baseline case characteristics are associated with the average level of cynicism over the four interviews, using an ordinary least squares regression approach that considers all the variables in a single step. The outcome variable, the average value of legal cynicism across the four waves, was obtained by summing the four cynicism scores and then dividing by four (M=2.03, SD=0.48). We used the same variables for this analysis as we did for the ANOVA's presented above.95 These results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

OLS Regression Predicting Average Legal Cynicism

| Variable | B | SE(B) |

|---|---|---|

| Age 15 | 0.042 | 0.051 |

| Age 16 | 0.056 | 0.048 |

| Age 17 | 0.078 | 0.050+ |

| Age 18 | −0.029 | 0.067 |

| Site | 0.025 | 0.037 |

| Priors | 0.026 | 0.011* |

| Age first | −0.007 | 0.010 |

| Black | 0.052 | 0.042 |

| Hispanic | 0.161 | 0.037* |

| Gender | −0.167 | 0.041* |

| Locked-up | 0.010 | 0.031 |

| PJ-Police-Overall | −0.046 | 0.032 |

| PJ-Court-Overall | −0.068 | 0.031* |

| Constant | 2.484 | 0.175* |

| R-Square | .054 |

p<.05 (2 tailed-test),

p<.10

Six variables attain significance in this model estimation. First, seventeen-year-old participants were more likely to have higher cynicism than their age-fourteen counterparts, though this result was only marginally significant. None of the other age groups differed from the age-fourteen participants. Additionally, individuals with a higher number of prior arrests in the past year were more likely to report a higher average cynicism across the eighteen-month follow-up period. Third, Hispanic juveniles were more likely than white juveniles to report higher cynicism. Fourth, females were less likely than males to have higher cynicism scores. Finally, with regard to the procedural justice perceptions, Table 5 shows that higher scores on the measure of procedural justice regarding the court are associated with lower average legal cynicism scores. In contrast, individuals' score on the procedural justice scale with regard to police practices does not significantly predict their score on the measure of legal cynicism.96

3. Legitimacy Trajectories

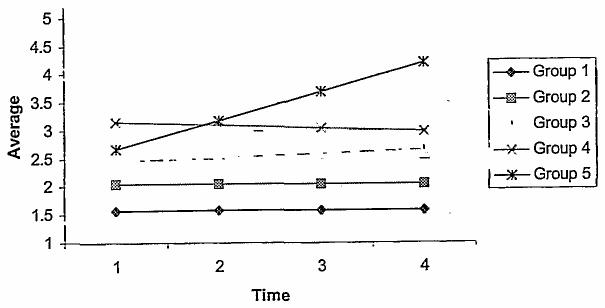

Next, we turned to a trajectory-based analysis of individuals' perceptions of the legitimacy of law over the eighteen-month follow-up period. A five-trajectory solution was the best fitting model, using the BIC decision rule. The plot for this solution is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Predicted Legitimacy Trajectories

Several findings are of interest in the legitimacy trajectory analysis. First, there are mean-level differences at the intercept (baseline) for all five groups. For example, at baseline, group 1 averages 1.50 (low legitimacy) while group 4 averages close to 3.0 (more legitimacy). Second, over 40% of the sample, groups 1 (10.1% of the sample) and 2 (32.6% of the sample), have very flat and stable trajectories over time. Groups 3 (42.2% of the sample) and 4 (13.4% of the sample), which are reasonably stable over the follow-up period, start at different baseline levels but appear to be converging by the eighteen-month period, with group 4 coming to perceive less legitimacy over time but group 3 perceiving somewhat more legitimacy over time. Third, the only group in which there is a dramatic increase in perceptions of legitimacy over time is very small—group 5 which accounts for only 1.7% of the sample. These individuals start out with relatively high legitimacy perceptions (close to 3.0) but increase to around 4.0 by the eighteen-month interview. Although this group is certainly of interest, it is important to note the very small number of individuals in this group. In short, with a few exceptions, for the majority of the study participants, there is very little change in perceptions of legitimacy across the eighteen-month period.

Again, we computed the maximum posterior membership probabilities for membership in the five legitimacy groups (see Table 6). Here, the mean assignment probabilities for each group are all quite high (i.e., all above .75) suggesting that the majority of individuals can be classified to a particular latent trajectory group with high probability. For group 1, the mean posterior probability was .819; for group 2, it was .774; for group 3, it was .802; for group 4, it was .815; and for group 5 it was .879.

Table 6.

Mean Posterior Probability Assignments—Legitimacy

| Group | Prob (G1) |

Prob (G2) |

Prob (G3) |

Prob (G4) |

Prob (G5) |

25th Percentile |

75th Percentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (n=114) | 0.819 | 0.179 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.69 | 0.96 |

| 2 (n=450) | 0.097 | 0.774 | 0.128 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.69 | 0.89 |

| 3 (n=607) | 0.000 | 0.118 | 0.802 | 0.075 | 0.003 | 0.71 | 0.91 |

| 4 (n=164) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.161 | 0.815 | 0.022 | 0.70 | 0.94 |

| 5 (n=20) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.016 | 0.104 | 0.879 | 0.68 | 0.99 |

4. What Factors Relate to Legitimacy?

In order to examine how the five groups vary along a set of baseline characteristics, we present a series of analysis-of-variance estimates. For the legitimacy analysis, we use the same variables employed in the prior analysis of scores on the measure of legal cynicism. These results may be found in Table 7.

Table 7.

Analysis of Variance—Legitimacy Means Presented By Group

| Variables | Group 1 |

Group 2 |

Group 3 |

Group 4 |

Group 5 |

F- Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | 1.201 | 1.382 | 1.538 | 1.695 | 1.900 | 28.479* |

| Priors past yr. | 1.04 | 1.02 | 0.96 | 0.69 | 0.55 | 2.619* |

| Age at first | 14.491 | 14.453 | 14.434 | 14.396 | 15.200 | 1.109 |

| Black | 0.631 | 0.517 | 0.370 | 0.189 | 0.050 | 24.585* |

| White | 0.105 | 0.160 | 0.224 | 0.286 | 0.350 | 5.918* |

| Hispanic | 0.219 | 0.284 | 0.357 | 0.445 | 0.550 | 6.724* |

| Gender | 1.09 | 1.10 | 1.15 | 1.19 | 1.40 | 6.498* |

| Locked-up | 0.403 | 0.377 | 0.324 | 0.250 | 0.150 | 3.703* |

| Age | 16.368 | 16.455 | 16.003 | 15.652 | 16.100 | 8.604* |

| Age 14 | 0.087 | 0.084 | 0.130 | 0.213 | 0.000 | 5.945* |

| Age 15 | 0.114 | 0.173 | 0.197 | 0.231 | 0.300 | 2.202 |

| Age 16 | 0.315 | 0.333 | 0.283 | 0.286 | 0.350 | 0.889 |

| Age 17 | 0.307 | 0.320 | 0.316 | 0.225 | 0.300 | 1.430 |

| Age 18 | 0.175 | 0.088 | 0.072 | 0.042 | 0.050 | 4.477* |

| PJ-Police (Overall) |

2.399 | 2.579 | 2.849 | 3.189 | 3.090 | 77.233* |

| PJ-Court (Overall) |

2.713 | 3.093 | 3.306 | 3.662 | 3.569 | 76.795* |

| PJ-Police (Direct) |

2.439 | 2.602 | 2.897 | 3.285 | 3.143 | 75.574* |

| PJ-Police (Indirect) |

2.281 | 2.512 | 2.707 | 2.900 | 2.920 | 20.574* |

| PJ-Court (Direct) |

2.731 | 3.156 | 3.381 | 3.834 | 3.733 | 60.770* |

| PJ-Court (Indirect) |

2.678 | 3.092 | 3.364 | 3.684 | 3.599 | 58.213* |

The results from the ANOVA analysis indicate that the five groups differ across sixteen variables: age (continuous), site, priors, African-American, white, Hispanic, locked-up, age-fourteen, and age-eighteen, gender, and all six procedural justice measures. As the table indicates, older individuals tend to hold lower perceptions of legitimacy while younger individuals are more likely found in group 4 who have relatively high perceptions of legitimacy. Regarding site, there are slightly more Phoenix participants in group 4 and 5, the two groups with the highest legitimacy scores. The two groups with the lowest legitimacy scores over time also have the highest number of prior arrests, while individuals in group 5 (the high legitimacy group) have the lowest number of prior arrests. Regarding race, while there are more African-Americans in groups 1 and 2 (the groups with the lowest legitimacy scores), there are more whites and Hispanics in the two groups (4 and 5) with the highest legitimacy values. The two low legitimacy groups (1 and 2) also had the highest values of lock-up, while the two high legitimacy groups (4 and 5) had the lowest values of lock-up. Two age coefficients were significantly different across the five groups: age-fourteen and age-eighteen: whereas there were a higher proportion of fourteen-year-olds in groups 3 and 4 (high but stable legitimacy scores), there were a higher number of eighteen-year olds in groups 1,2, and 3 having the lowest legitimacy scores. Females were more likely to be in the higher legitimacy group than they were to be in the lower legitimacy group. Finally, the legitimacy groups differed along all six procedural justice dimensions. Across these comparisons, the two groups with the lowest legitimacy (1 and 2) consistently scored lowest on all six procedural justice markers, whereas the two groups with the highest legitimacy (4 and 5) consistently scored higher on all six procedural justice markers.

As was the case for legal cynicism, there was great stability in perceptions of legitimacy over the eighteen-month period. Because of this, we investigated how the baseline characteristics predicted average legitimacy scores. This outcome variable, the average value of legitimacy, was obtained by summing the four cynicism scores and then dividing by four (M=2.38, SD=0.49). These results can be found in Table 8.

Table 8.

OLS Regression Predicting Average Legitimacy

| Variable | B | SE(B) |

|---|---|---|

| Age 15 | −0.058 | 0.044 |

| Age 16 | −0.090 | 0.042* |

| Age 17 | −0.078 | 0.044+ |

| Age 18 | −0.098 | 0.058+ |

| Site | 0.115 | 0.032* |

| Priors | −0.012 | 0.010 |

| Age first | −0.001 | 0.008 |

| Black | −0.125 | 0.036* |

| Hispanic | −0.015 | 0.032 |

| Gender | 0.082 | 0.035* |

| Locked-up | −0.082 | 0.027* |

| PJ-Police-Overall | 0.272 | 0.028* |

| PJ-Court-Overall | 0.223 | 0.027* |

| Constant | 0.829 | 0.152* |

| R-Square | 0.333 |

p<.05 (2 tailed-test),

p<.10

As can be seen, a number of variables attain significance in this model estimation. First, while all four age effects are negative indicating that compared to fourteen-year-olds, older individuals are less likely to hold high legitimacy perceptions, only the coefficient for sixteen-year-olds attains significance at p<.05, whereas the age-seventeen and age-eighteen groups are marginally significantly different from the fourteen-year-olds. Second, Phoenix juveniles are more likely to have higher perceptions of legitimacy than Philadelphia juveniles. Third, compared to whites, African-Americans report lower legitimacy perceptions. Fourth, individuals who were locked-up were more likely to have lower perceptions of legitimacy. Fifth, females are more likely than males to have higher legitimacy perceptions. Finally, measures of procedural justice with respect to both police and court procedures were significant in predicting average legitimacy scores. Individuals with higher procedural justice perceptions regarding both the police and the courts were more likely to hold higher average legitimacy scores.97

5. Concordance Between Legal Cynicism and Legitimacy Trajectories

It is also of interest to examine the common ground of group membership for both legal cynicism and legitimacy. It is expected that individuals who hold highly cynical attitudes towards the law will be less likely to afford legitimacy to the law and legal procedures.98 Table 9 presents a cross-tabulation of the four-group legal cynicism model and the five-group legitimacy model. Several findings emerge in this simple cross-tabulation. First, we confirm the negative relationship between legal cynicism and legitimacy (described earlier in Table 2).99 The two variables are significantly related to one another (χ = 167.605, p<.001) and modestly associated (Φ = .352). Second, individuals with the lowest reported cynicism (groups 1 and 2) also report high legitimacy perceptions. In fact, of the twenty individuals who reported the highest perceptions of legitimacy (group 5), 19 were in one of the two lowest legal cynicism groups, 1 (12) and 2 (7). Third, of the forty-six individuals in the highest cynicism group (4), forty-one of them, or 89%, are found in the two lowest legitimacy groups (16 are in group 1 and 25 in group 2), confirming the expectation raised above.

Table 9.

Cross-Tabulation of 4-Group Legal Cynicism and 5-Group Legitimacy Trajectories. Observed values shown first, expected values in parentheses.

| Cynicism | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legitimacy | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | Total |

| Group 1 | 18 (19.8) | 42 (51.2) | 38 (39.2) | 16 (3.9) | 114 |

| Group 2 | 47 (78.0) | 179 (201.9) | 199 (154.8) | 25 (15.3) | 450 |

| Group 3 | 99 (105.3) | 306 (272.4) | 197 (208.8) | 5 (20.6) | 607 |

| Group 4 | 59 (28.4) | 74 (73.6) | 31 (56.4) | 0 (5.6) | 164 |

| Group 5 | 12 (3.5) | 7 (9.0) | 1 (6.9) | 0 (0.7) | 20 |

| Total | 235 | 608 | 466 | 46 | 1355 |

6. Alternative Stratified Trajectory Specifications

In a series of supplemental analyses, we also estimated trajectories of legal cynicism and legitimacy by stratifying the sample as to whether they had any priors in the year before the baseline interview (no/yes), by lock-up status at baseline (no/yes), and then for each of the age groups between fourteen and eighteen. In each of these analyses, the results indicated that individuals' perceptions of the legitimacy of law as well as their degree of cynicism about the legal system were stable over time. That is, although individuals with priors reported different baseline levels of legitimacy and legal cynicism compared to first-time offenders, both groups' perceptions were highly stable over time. The same finding emerged for individuals who were and were not locked-up. Finally, the stratified age analyses also revealed stability within each age group (fourteen through eighteen) in both legal cynicism and legitimacy, but different intercepts at baseline.100

C. DISCUSSION

This was the first study of the longitudinal, within-individual trajectories of two fundamental aspects of legal socialization—legal cynicism and legitimacy of law—among a large sample of serious juvenile offenders. Three main findings emerged from our effort.

The first and most important is the strong stability of both legal cynicism and legitimacy over the eighteen-month period after court disposition among this group of serious adolescent offenders. With few exceptions, there was little developmental change in these dimensions of legal socialization over time, and this was the case both overall as well as within subgroups defined by the number of priors, lock-up status, and age. At the same time, while there does not appear to be a significant amount of systematic change in these variables, there is some oscillation (i.e., movement away) over the eighteen-month period away from the mean.

Second, although individuals' cynicism about the legal system and perceptions of the legitimacy of law were highly stable over time, they do vary in mean levels of legitimacy and legal cynicism, and these mean differences were consistently related to other factors. For example, individuals with more priors reported greater cynicism than individuals with fewer priors, and Hispanics reported more cynicism than whites. On the other hand, when we examined the determinants of legitimacy, we found strong age effects, such that older individuals were less likely to perceive the law as legitimate than were fourteen-year-olds. In light of the fact that very few individuals in the sample as a whole evinced change in perceptions of legitimacy over time, this may indicate that perceptions of the law's legitimacy change very little after age fourteen, perhaps because these more general and less situational sorts of attitudes and beliefs have become strongly entrenched. Additionally, juveniles who were locked-up, as well as African-Americans, were more likely to have lower legitimacy perceptions compared to juveniles not locked-up and whites. Finally, we also found consistent evidence regarding the relationship between the more situationally-based procedural justice perceptions and both measures of legal socialization. Across all comparisons, individuals with high procedural justice perceptions regarding the police and the courts tended to have lower legal cynicism and higher legitimacy, thereby suggesting that situational experiences with criminal justice personnel influence more general attitudes about the law and legal system.

Third, when we cross-tabulated the trajectories of legal cynicism and legitimacy we found that individuals who reported the lowest legal cynicism also reported the highest legitimacy, while individuals reporting the highest cynicism were highly likely to also report lower legitimacy. In conjunction, these two faces of legal socialization provide detailed information about the experience-based normative orientation of adolescents with respect to the law and legal actors.

Although the results are the first longitudinal analyses in the legal socialization literature, our data are limited in some respects. First, the trajectory methodology itself has some shortcomings. Because it assumes that unobserved heterogeneity is drawn from a discrete (multinomial) probability distribution, there may be model misspecification bias if unobserved individual differences are actually drawn from a continuous distribution. Also, classification of individuals to distinctive groups will never be perfect,101 a finding that is somewhat mitigated by the relatively strong posterior probability assignments observed herein, and the confirmatory substantive results observed in the cross-tabulation analysis. Still, care should be taken on the reification of distinct groups of legal cynicism and/or legitimacy.

Second, our data assessed perceptions of legal socialization over an eighteen-month time period. It may be that this is not long enough to observe change. We believe that it is a sufficiently long period, however, because (a) the deterrence literature indicates that perceptions change even over three month time periods and (b) as a serious offender sample, participants in this study are likely to have many experiences of criminal justice contact, either through personal or vicarious channels,102 which should increase the likelihood of finding change in attitudes and beliefs. It may be that the ingredients that beliefs, attitudes, and legal socialization are comprised of, is more enduring and less likely to be impacted by experiences with the criminal justice system than the ‘perceptions’ and the objective ‘knowledge’ of the criminal justice system that may be affected by sanctions. This may be an important distinction to highlight in future research because of its potential to inform us of the types of impact the criminal justice system has and does not have on offenders.

Third, our findings of stability in legal socialization may be due to the fact that we captured our sample during an age range where there simply is not much change. That is, much of the instability of perceptions may occur earlier in life (i.e., before fourteen) or in adulthood (i.e., after twenty-one). Alternatively, the finding of stability may reflect some sort of selection effect in that these adolescents have experienced variability in cynicism and legitimacy but after numerous contacts with the criminal justice system their levels of legal socialization become established (i.e., stable). Recent work by Fagan and Tyler suggests that this indeed is the case.103 Using a community sample from two New York City neighborhoods, they showed that both legitimacy and legal cynicism changed over time from ages ten through fourteen, and then became more stable by age sixteen. Legal cynicism and legitimacy were well predicted by the quality of respondents' experiences with the police, but not necessarily by the extent of contact, either direct or vicarious through peers and family members. This suggests that the stability in this adolescent offender sample may not be an artifact of selection of persons with more frequent and intense contacts with legal authorities, but instead may be a robust finding that applies both to offenders and non-offenders.

Fourth, because our effort was primarily descriptive, we did not document the pre- and post-adolescent characteristics that are associated with changes in legal socialization and how these changes influence criminal activity and compliance into adulthood. It is of great interest and import to examine whether, and which specific types of, external events/experiences influence legal socialization trajectories over time.104 Finally, it was beyond the scope of the current study to examine the source/origin of perceptions of legitimacy and legal cynicism. Since parents tend to be one of—if not the primary—socializing agent in adolescents' lives influencing their moral values, and religious and political beliefs,105 it would be particularly useful in subsequent research to examine the concordance of parent-child perceptions of legal socialization to determine the extent to which parents and children share similar legal socialization perceptions.

These limitations notwithstanding, our effort provides the first depiction of how two distinct legal socialization constructs, legal cynicism and legitimacy, unfold over time in a sample of serious juvenile offenders. Based on the evidence in the deterrence/compliance literatures, we had suspected that we would find evidence to suggest that such perceptions would be more dynamic than the static results observed. Theories of justice generally, and procedural justice/legal socialization in particular, have not said much about the longitudinal patterning of legal socialization during adolescence. Our results indicate that some heavy theoretical lifting is in order to understand why such perceptions are highly stable. Granted, this may be due to the fact that we used an offender-based sample, but we would be very surprised if this was the driving force behind the stability of such perceptions. It is critical that other researchers collect the requisite data to determine the replicability of our results.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The magazine publisher is the copyright holder of this article and it is reproduced with permission. Further reproduction of this article in violation of the copyright is prohibited. To contact the publisher: http://www.press.uillinois.edu/journals/jclc.html

Contributor Information

ALEX R. PIQUERO, University of Florida

JEFFREY FAGAN, Columbia University.

EDWARD P. MULVEY, University of Pittsburgh

LAURENCE STEINBERG, Temple University.

CANDICE ODGERS, University of Virginia.

References

- 1.Tyler Tom R., Huo Yuen J. Trust in the Law: Encouraging Public Cooperation with the Police and Courts. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sampson Robert J., Bartusch Dawn Jeglum. Legal Cynicism and (Subcultural?) Tolerance of Deviance: The Neighborhood Context of Racial Differences. Law & Soc'y Rev. 1998;32:777. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tyler Tom R. Why People Obey the Law: Procedural Justice, Legitimacy and Compliance. 1990 hereinafter Tyler, Why People Obey the Law. [Google Scholar]

- 4.See, e.g., Anderson Elijah. Code of the Street: Decency, Violence, and the Moral Life of the Inner City. 1st ed. 1999.

- 5.See Tyler Tom R., et al. Social Justice in a Diverse Society. 1997 Fagan Jeffrey A., Tyler Tom R. Legal Socialization of Children and Adolescents. Soc. Just. Res. 2006 forthcoming.

- 6.Easton David, Dennis Jack. Children in the Political System: Origins of Political Legitimacy. 1969 [Google Scholar]

- 7.See Tapp June Louin, Levine Felice J., editors. Law, Justice, and the Individual in Society: Psychological and Legal Issues. 1977. Tapp June Louin, Kohlberg Lawrence. Developing Sense of Law and Legal Justice. J. Soc. Issues. 1971;27:65.

- 8.Cohn Ellen S., White Susan O. Legal Socialization: A Study of Norms and Rules. 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flanagan Constance A. Volunteerism, Leadership, Political Socialization, and Civic Engagement. In: Lemer Richard, Steinberg Laurence., editors. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.See Tyler, Huo supra note 1. Fagan, Tyler supra note 5.

- 11.See Cohn, White supra note 8. Sherman Lawrence W. Defiance, Deterrence, and Irrelevance: A Theory of the Criminal Sanction. J. Res. Crim. & Delinquency. 1993;30:445.

- 12.See Easton, Dennis supra note 6. Hirschi Travis. Causes of Delinquency. 1969 Tyler Why People Obey The Law. supra note 3.

- 13.Fagan, Tyler supra note 5.

- 14.Cf. Cohn, White supra note 8. Hagan John, et al. Race, Ethnicity, and Youth Perceptions of Criminal Injustice. Am. Soc. Rev. 2005;70:381.

- 15.Cf. Tyler, Huo supra note 1.

- 16.Paternoster Raymond, et al. Do Fair Procedures Matter? The Effect of Procedural Justice on Spousal Assault. Law & Soc'y Rev. 1997;31:163. [Google Scholar]

- 17.See Laub John H., Sampson Robert J. Understanding Desistance from Crime. Crime & Just. 2001;28:1.

- 18.Mill John Stuart. John Stuart Mill's Philosophy of Scientific Method. Hafher: 1950. 1963. [Google Scholar]; Kant Immanuel. In: The Metaphysical Elements of Justice. Ladd J, editor. Bobbs-Merrill Co.; 1797. 1965. [Google Scholar]; Rawls John. A Theory of Justice. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; 1971. 1999. [Google Scholar]; Sarat Austin. Studying American Legal Culture: An Assessment of Survey Evidence. Law & Soc'y Rev. 1977;11:427. [Google Scholar]

- 19.See, e.g., Andenaes Johannes. Punishment and Deterrence. 1974 Zimring Franklin E., Hawkins Gordon. Deterrence: The Legal Threat in Crime Control. University of Chicago Press; 1973.

- 20.Tyler Why People Obey the Law. supra note 3. [Google Scholar]; Tyler Tom R. Procedural Justice, Legitimacy and the Effective Rule of Law. In: Tonry Michael., editor. Crime & Justice: A Review of Research. Vol. 30. 2003. hereinafter Tyler, Procedural Justice. [Google Scholar]

- 21.See, e.g., Lind E. Allen, Tyler Tom R. The Social Psychology of Procedural Justice. Univ. of Waterloo; 1998. Thibaut John W., Walker Laurens. Procedural Justice: A Psychological Analysis. 1975

- 22.Tyler Procedural Justice. supra note 20. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohn, White supra note 8.

- 24.Tyler, Huo supra note 1.

- 25.Tyler Procedural Justice. :307. supra note 20. [Google Scholar]

- 26.p. 309. Id.

- 27.Tyler Why People Obey the Law. supra note 3. [Google Scholar]; Tyler, Huo supra note 1.

- 28.Sampson, Bartusch supra note 2.; Srole Leo. Social Integration and Certain Corollaries: An Exploratory Study. Am. Soc. Rev. 1956;21:709. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Srole supra note 28.

- 30.Sampson, Bartusch supra note 2.

- 31.p. 786. Id.

- 32.Steinberg Laurence, Morris Amanda S. Adolescent Development. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 2001;52:83. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.See, e.g., Tyler Why People Obey the Law. supra note 3.

- 34.See Cohn, White supra note 8. Easton David. A Systems Analysis of Political Life. 1965 Krislov S, et al. Compliance and the Law. 1966 Law, Justice, and the Individual in Society: Psychological and Legal Issues. supra note 7. Parsons Talcott, Shils Edward A. Toward a General Theory of Action. 1951 Melton Gary B., editor. Neb. Symposium on Motivation. Vol. 33. 1985. The Law as a Behavioral Instrument. see also Caspi A, Moffitt TE. The Continuity of Maladaptive Behavior: From Description to Understanding in the Study of Antisocial Behavior. In: Cicchetti E, Cohenen D, editors. Manual of Developmental Psychopathology. 1993. Niemi RG. Political Socialization. In: Knutson Jeanne N., editor. The Handbook of Political Psychology. 1973.

- 35.As stated earlier, there have been no longitudinal, within-person assessments of legal socialization among adolescents. That said, we have reason to believe that, like more general deterrence- and compliance-based processes and frameworks, legal socialization should vary over time.

- 36.Homel Ross. Policing and Punishing the Drinking Driver: A Study of General and Specific Deterrence. 1988 [Google Scholar]; Pogarsky Greg, et al. Modeling Change in Perceptions About Sanction Threats: The Neglected Linkage in Deterrence Theory. J. Quantitative Criminology. 2004;20:343. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Minor WW, Harry JP. Deterrent and Experiential Effects in Perceptual Deterrence Research: A Replication and Extension. J. Res. Crime & Delinq. 1982;19:190. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paternoster Raymond, et al. Estimating Perceptual Stability and Deterrent Effects: The Role of Perceived Legal Punishment in the Inhibition of Criminal Involvement. J. Crim. L. & Criminology. 1983;74:270. [Google Scholar]

- 39.pp. 281–85. Id.

- 40.Paternoster Raymond, et al. Assessments of Risk and Behavioral Experience: An Exploratory Study of Change. Criminology. 1985;23:425–27. 417. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Id.

- 42.Id.

- 43.Id.

- 44.Tyler Procedural Justice. supra note 20. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Compare Fagan, Tyler supra note 5.; with Tyler, Huo supra note 1., and Sunshine Jason, Tyler Tom R. The Role of Procedural Justice and Legitimacy in Shaping Public Support for Policing. Law & Soc'y Rev. 2003;37:513.

- 46.See Tyler Procedural Justice. supra note 20.

- 47.Sampson, Bartusch p. 778. supra note 2.

- 48.p. 782. Id.

- 49.p. 793. Id.

- 50.p. 797. Id.

- 51.Tyler Why People Obey the Law. supra note 3. [Google Scholar]

- 52.p. 638. Id.

- 53.Id.

- 54.Fagan, Tyler supra note 5.

- 55.Id.

- 56.Tyler Tom R., et al. Maintaining Allegiance Toward Political Authorities: The Role of Prior Attitudes and the Use of Fair Procedures. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 1989;33:629. 633. hereinafter Tyler et al., Maintaining Allegiance. [Google Scholar]

- 57.p. 638. Id.

- 58.Miller Steven D., Sears David O. Stability and Change in Social Tolerance: A Test of the Persistence Hypothesis. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 1986;30:218–19. 214. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Id.

- 60.Fagan, Tyler supra note 5.

- 61.Id.

- 62.Id.

- 63.Email from Tyler Tom R. Professor of Psychology, N.Y. Univ., to Alex R. Piquero, Professor, Univ. of Fla. 2005 Jan. 18 08:10:08 EST. on file with the author.

- 64.Tyler, et al. Maintaining Allegiance. :633. supra note 56. [Google Scholar]

- 65.See, e.g., Paternoster Ray, Piquero Alex R. Reconceptualizing Deterrence: An Empirical Test of Personal and Vicarious Experiences. J. Res. Crime & Delinquency. 1995;32:251. Piquero Alex R., Paternoster Ray. An Application of Stafford and Warr's Reconceptualization of Deterrence to Drinking and Driving. J. Res. Crime & Delinquency. 1998;35:3. Piquero Alex R., Pogarsky Greg. Beyond Stafford and Warr's Reconceptualization of Deterrence: Personal and Vicarious Experiences, Impulsivity, and Offending Behavior. J. Res. Crime & Delinquency. 2002;39:153. Stafford Mark C., Warr Mark. A Reconceptualization of General and Specific Deterrence. J. Res. Crime & Delinquency. 1993;30:123.

- 66.See Laub, Sampson supra note 17.

- 67.Mulvey Edward P., et al. Theory and Research on Desistance from Antisocial Activity Among Serious Adolescent Offenders. Youth Violence & Juv. Just. 2004;2:213. doi: 10.1177/1541204004265864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schubert Carol A., et al. Operational Lessons from the Pathways to Desistance Project. Youth Violence & Juv. Just. 2004;2:237. doi: 10.1177/1541204004265875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Baseline and follow-up scores on both the legal cynicism and legitimacy scales did not differ significantly if the survey was administered prior to—or just after—the case disposition.

- 70.Sampson, Bartusch supra note 2.

- 71.Srole supra note 28.

- 72.Tyler Why People Obey the Law. supra note 3. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tyler, Huo supra note 1.

- 74.Nagin Daniel S., Tremblay Richard E. Developmental Trajectory Groups: Fact or Fiction? Criminology. 2005;43:873. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nagin Daniel S., Land Kenneth C. Age, Criminal Careers, and Population Heterogeneity: Specification and Estimation of a Nonparametric, Mixed Poisson Model. Criminology. 1993;31:327. 333. [Google Scholar]

- 76.See Nagin Daniel S. Group-Based Modeling of Development Over the Life Course. 2004 Nagin Daniel S. Analyzing Developmental Trajectories: A Semi-parametric, Group-based Approach. Psychological Methods. 1999;4:139. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.6.1.18. Piquero Alex R. Taking Stock of Developmental Trajectories of Criminal Activity Over the Life Course. 2004. unpublished manuscript. This paper was presented at the National Institute of Justice Conference on “What Have We Learned from Longitudinal Studies” in October 2004 in Washington, D.C.

- 77.Nagin, Tremblay p. 10. supra note 70.

- 78.p. 5. Id.

- 79.Schwarz Gideon. Estimating the Dimension of a Model. Annals Stat. 1978;6:461. [Google Scholar]

- 80.D'Unger Amy V., et al. How Many Latent Classes of Delinquent/Criminal Careers? Results from Mixed Poisson Regression Analyses. Am. J. Soc. 1998;103:1593. [Google Scholar]

- 81.p. 1627. Id.; Id. According to D'Unger:[T]his statistical criterion favors model parsimony by extracting a penalty for complicating a model (by adding parameters) that increases with the log of the sample size. Furthermore, this BIC (or Schwarz) criterion for model selection embodies the intuitive notion that, when the analyst complicates a model by adding parameters, the payoff in terms of a decrease in the log maximized-likelihood function of the model should be larger than this penalty.

- 82.Nagin, Tremblay pp. 16–17. supra note 74. It must be recognized, of course, that the trajectory methodology is not the only approach one could take to study these issues. Piquero supra note 76. Alternative methods exist, principally hierarchical modeling and latent curve modeling. One of the key differences between the trajectory approach and these other methods is that the latter treat the population distribution of the variable of interest as continuous whereas the trajectory model approximates this continuous distribution with points of support, or groups. The trajectory method, then, is designed to identify distinctive, developmental trajectories within the population, to calibrate the probability of population members following each such trajectory, and to relate those probabilities to covariates of interest. Nagin p. 153. supra note 76. It is important to bear in mind here that the variation within the trajectory is random variation conditional on trajectory (group) membership, while the variation between the trajectories is structural. Stephen Raudenbush provides a further clarification of the issues surrounding the various methodologies: “In many studies of growth it is reasonable to assume that all participants are growing according to some common function but that the growth parameters vary in magnitude.” Raudenbush Stephen. Toward a Coherent Framework for Comparing Trajectories of Individual Change. In: Collins Linda M., Sayer Aline G., editors. New Methods for the Analysis of Change. Vol. 59 2001. He offered children's vocabulary growth curves as an example of such a growth process. Two distinctive features of such developmental processes are (a) they are generally monotonic(3— thus, the term growth—and (b) they vary regularly within the population. For such processes it is natural to ask, “What is the typical pattern of growth within the population and how does this typical growth pattern vary across population members?” Hierarchical and latent curve modeling are specifically designed to answer such a question. Raudenbush also offered an example of a developmental process—namely, depression—that does not generally change monotonically over time and does not vary regularly through the population. He observed, “It makes no sense to assume that everyone is increasing (or decreasing) in depression. … [M]any persons will never be high in depression, others will always be high; some are recovering from serious depression, while others will become increasingly depressed.” p. 59. Id. For problems such as this, he recommended the use of a multinomial-type method because development, or modeled trajectories, varies regularly across population members. Indeed, some trajectories vary greatly across population subgroups both in terms of the level of behavior at the outset of the measurement period and in the rate of growth and decline over time. According to Raudenbush, the trajectory methodology is “especially useful when trajectories of change involve sets of parameters that mark qualitatively different kinds of development.” For such problems, a modeling strategy designed to identify averages and explain variability about that average is far less useful than a group-based strategy designed to identify distinctive clusters of trajectories and to calibrate how characteristics of individuals and their circumstances affect membership in these clusters. p. 60. Id.

- 83.Tables containing the final parameter estimates for all models shown herein are available upon request.

- 84.See Tyler Why People Obey the Law. supra note 3. Tyler Procedural Justice. supra note 20.

- 85.Tyler Tom R. Procedural Fairness and Compliance with the Law. Swiss J. Econ. & Stat. 1997;133:219. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Agnew Robert. Foundation for a General Strain Theory of Crime and Delinquency. Criminology. 2002;30:47. [Google Scholar]; Piquero Alex R., et al. Discerning Unfairness Where Others May Not: Low Self-control and Unfair Sanction Perceptions. Criminology. 2004;42:699. [Google Scholar]; Sherman supra note 11.

- 87.Hirschi supra note 12.

- 88.Braithwaite John. Crime, Shame, and Reintegration. 1989 [Google Scholar]

- 89.See Tyler Why Do People Obey the Law. supra note 3. Paternoster, et al. supra note 16.

- 90.See Tyler Why Do People Obey the Law. supra note 3. Tyler, Huo supra note 1. Paternoster, et al. supra note 16.

- 91.Tyler Why Do People Obey the Law. supra note 3. [Google Scholar]; Sunshine Jason, Tyler Tom R. The Role of Procedural Justice and Legitimacy in Shaping Public Support for Policing. Law & Soc'y Rev. 2003;37:513. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tyler Why Do People Obey the Law. supra note 3. [Google Scholar]; Tyler, Huo supra note 1.; Leventhal GS. What Should be Done with Equity Theory: New Approaches to the Study of Fairness in Social Relationships. In: Gergen Kenneth J., et al., editors. Social Exchange. 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 93.The items in this measure are divided into two sections: Police [Direct Experience & Others Experience (e.g., “The police treat me the same way they treat most people my age.”)] and Judge [Direct Experience & Others Experience (e.g., “The court considered the evidence/viewpoints in this incident fairly.”)]. Higher values for all indicators mean better (or more) procedural justice. The two procedural justice variables (police and court) are positively correlated (r = .51, p<.05), but not sufficiently so as to warrant multicollineariry concerns. Six summary variables were formed: (1) procedural justice police—overall (nineteen items, range 1.39-4.49), (2) procedural justice police—direct experience (fourteen items, range 1.15-4.63), (3) procedural justice police—others experience (five items, range 1.00-5.00), (4) procedural justice court—overall (nineteen items, range 1.18-5.40), (5) procedural justice court—direct experience (fourteen items, range 1.23-7.00), and (6) procedural justice court—others experience (seven items, range 1.15-5.00). A one-factor CFA was conducted for each of the scores generated above, and the values produced from this analysis are as follows: (1) procedural justice scales for police—direct experience (alpha: 74; NFI: .79; NNFI: .78; CFI: .81; RMSEA: .08. A second model which dropped two items from the scale was also fit to the data; however, nothing was gained by dropping the two items so the one-factor model using all items was retained); (2) procedural justice scales for police—others experience (alpha: 57; NFI: .96; NNFI: .93; CFI: .97; RMSEA: .06.); (3) procedural justice scales in court—direct experience (alpha: 75; NFI: .80; NNFI: .78; CFI: .82; RMSEA: .07. A second model which dropped two items from the scale was also fit to the data; however, nothing was gained (i.e., better fit) by dropping the two items, thus the one-factor model using all items was used.); (4) procedural justice scales in court—others experience (alpha: 66; NFI: .93; NNFI: .90; CFI: .94; RMSEA: .08). A detailed listing of the items and coding mechanism is available upon request.

- 94.Tyler Why People Obey the Law. supra note 3. [Google Scholar]

- 95.The only modification to the OLS estimates was our use of age fourteen as the reference group for the age dummies and white as the reference groups for the race dummies.