Abstract

Featuring a high level of taxon sampling across Ascomycota, we evaluate a multi-gene phylogeny and propose a novel order and class in Ascomycota. We describe two new taxa, Geoglossomycetes and Geoglossales, to host three earth tongue genera: Geoglossum, Trichoglossum and Sarcoleotia as a lineage of ‘Leotiomyceta’. Correspondingly, we confirm that these genera are not closely related to the genera Neolecta, Mitrula, Cudonia, Microglossum, Thuemenidum, Spathularia and Bryoglossum, all of which have been previously placed within the Geoglossaceae. We also propose a non-hierarchical system for naming well-resolved nodes, such as ‘Saccharomyceta’, ‘Dothideomyceta’, and ‘Sordariomyceta’ for supraordinal nodes, within the current phylogeny, acting as rankless taxa. As part of this revision, the continued use of ‘Leotiomyceta’, now as a rankless taxon, is proposed.

Keywords: Bayesian inference, hybrid classification, maximum likelihood

INTRODUCTION

The multi-gene sequence datasets generated by the research consortium ‘Assembling the Fungal Tree of Life’ (AFTOL) have resulted in several multi-gene phylogenies incorporating comprehensive taxon sampling across Fungi (Lutzoni et al. 2004, Blackwell et al. 2006, James et al. 2006). AFTOL generated a data matrix spanning all currently accepted classes in the Ascomycota, the largest fungal phylum. The phylogenies produced by AFTOL prompted the proposal of a phylogenetic classification from phylum to ordinal level in fungi (Hibbett et al. 2007). Although the Botanical Code does not require the principle of priority in ranks above family (McNeill et al. 2006), this principle was nevertheless followed for all taxa. The following ranked taxa were defined: subkingdom, phylum (suffix -mycota, except for Microsporidia), subphylum (-mycotina), class (-mycetes), subclass (-mycetidae) and order (-ales). As in Hibbett et al. (2007), several phylogenetically well-supported nodes above the rank of order could not be accommodated in the current hierarchical classification system based on the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature. To remedy this deficiency, rankless (or unranked) taxa for unambiguously resolved nodes with strong statistical support was proposed (Hibbett & Donoghue 1998). Hybrid classifications that include both rankless and Linnaean taxa have since been discussed elsewhere (Jørgensen 2002, Kuntner & Agnarsson 2006), and applied to diverse organisms from lichens (Stenroos et al. 2002) and plants (Sennblad & Bremer 2002, Pfeil & Crisp 2005) to spiders (Kuntner 2006). These studies all attempt to create a comprehensive code for phylogenetic nomenclature that retains the current Linnean hierarchical codes.

In keeping with the practice of previous hybrid classifications, we propose to use names corresponding to clades of higher taxa that were resolved in this phylogeny as well as preceding studies. The proposed informal, rankless names for well-supported clades above the class level in our phylogeny agrees with the principles of the Phylocode (http://www.ohio.edu/phylocode/). It is our hope that such names should function as rankless taxa, facilitating the naming of additional nodes/clades as they become resolved. Eventual codification will follow the example of Hibbett et al. (2007) by applying principles of type names and priority. A number of published manuscripts already provide background on other supraordinal relationships of Fungi; for more complete treatments of the various classes, see Blackwell et al. (2006).

During the AFTOL project a data matrix was generated spanning all currently accepted classes in the Ascomycota, the largest fungal phylum. A multi-gene phylogeny was recently inferred from these data, demonstrating relevant patterns in biological and morphological character development as well as establishing several distinct lineages in Ascomycota (Schoch et al. 2009). Here we test whether the relationships reported in Schoch et al. (2009) remain valid by applying both maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian analyses on a more restricted but denser set of taxa, including expanded sampling in the Geoglossaceae.

We will therefore address the taxonomic placement of a group of fungi with earth tongue morphologies that are shown to be unrelated to other known classes. This morphology is closely associated with the family Geoglossaceae (Corda 1838). With typical inoperculate asci and an exposed hymenium, Geoglossaceae has long been thought to be a member of Leotiomycetes, though the content of the family itself has experienced many changes (Nannfeldt 1942, Korf 1973, Spooner 1987, Platt 2000, Wang et al. 2006a, b). It is currently listed with 48 species and 6 genera in the Dictionary of the Fungi (Kirk et al. 2008). Several analyses using molecular data supported a clade including three earth tongue genera, Geoglossum, Trichoglossum and Sarcoleotia (Fig. 1), and cast doubt upon their positions in Leotiomycetes (Platt 2000, Gernandt et al. 2001, Lutzoni et al. 2004, Sandnes 2006, Spatafora et al. 2006, Wang et al. 2006b). Here we present a comprehensive phylum-wide phylogeny, including data from protein coding genes. We can confidently place the earth tongue family as separate from currently accepted classes in Ascomycota.

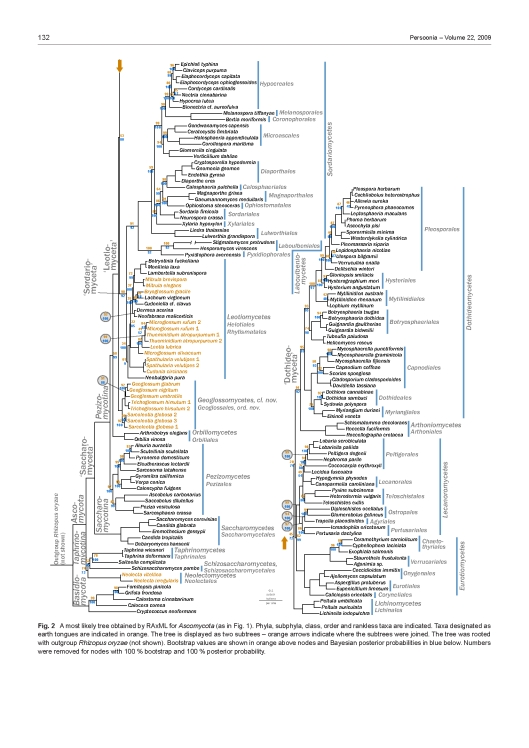

Fig. 1.

A most likely tree obtained by RAxML for Ascomycota. Subphyla, class and rankless taxa are indicated. Classes containing fungi designated as earth tongues are indicated in black. The tree was rooted with outgroup Rhizopus oryzae (not shown). Bootstrap values are shown in orange and Bayesian posterior probabilities in blue. Orange, bold branches are supported by more than 80 % bootstrap and 95 % posterior probability, respectively. The full phylogeny, without collapsed clades, are shown in Fig. 2. The inset figures illustrate morphological ascomal diversity in the earth tongues. The species are as follows: A. Trichoglossum hirsutum; B. Geoglossum nigritum; C. Microglossum rufum; D. Spathularia velutipes; E. Geoglossum nigritum. Photo credits: A: Zhuliang Yang; B, D, E: Kentaro Hosaka; C: Dan Luoma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data were extracted from the complete data matrix obtained from the WASABI database (www.aftol.org), incorporating representatives for all currently accepted classes, and maximizing the number of orders and available data. Following the approach of James et al. (2006) we performed a combined analysis, with both DNA and amino acid data, while allowing for missing data. This data was supplemented with additional ribosomal sequences from earth tongue genera obtained and deposited in GenBank from two previous studies (Wang et al. 2006a, b). To further minimise poorly aligned areas, 219 additional columns, which proved variable when viewed in BioEdit with a 40 % shade threshold, were excluded from the original AFTOL inclusion set. The refined dataset consisted of 161 taxa (including outgroups) and 4 429 characters for six different loci: the nuclear small and large ribosomal subunits (nSSU, nLSU), the mitochondrial small ribosomal subunit (mSSU) and fragments from three proteins: transcription elongation factor 1 alpha (TEF1) and the largest and second largest subunits of RNA polymerase II (RPB1, RPB2). A complete table with the published GenBank numbers is listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Taxa and sequences used in this study.

| AFTOL no. | Class | Order | Voucher1 | Taxon | nSSU | nLSU | mSSU | RPB1 | RPB2 | TEF1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1241 | Zygomycota outgroup | GB | Rhizopus oryzae | AF113440 | AY213626 | AY863212 | Genome | Genome | Genome | |

| 438 | Basidiomycota outgroup | GEL 5359 | Calocera cornea | AY771610 | AY701526 | AY857980 | AY536286 | AY881019 | ||

| 439 | Basidiomycota outgroup | AW 136 | Calostoma cinnabarinum | AY665773 | AY645054 | AY857979 | AY780939 | AY879117 | ||

| 1088 | Basidiomycota outgroup | GB | Cryptococcus neoformans | Genome | Genome | XM_570943 | XM_570204 | Genome | ||

| 770 | Basidiomycota outgroup | MB 03-036 | Fomitopsis pinicola | AY705967 | AY684164 | FJ436112 | AY864874 | AY786056 | AY885152 | |

| 701 | Basidiomycota outgroup | DSH s.n. | Grifola frondosa | AY705960 | AY629318 | AY864876 | AY786057 | AY885153 | ||

| 126 | Arthoniomycetes | Arthoniales | Diederich 15572 | Roccella fuciformis | AY584678 | AY584654 | EU704082 | DQ782825 | DQ782866 | |

| 93 | Arthoniomycetes | Arthoniales | BG Printzen1981 | Roccellographa cretacea | DQ883705 | DQ883696 | FJ772240 | DQ883713 | DQ883733 | |

| 307 | Arthoniomycetes | Arthoniales | DUKE 0047570 | Schismatomma decolorans | AY548809 | AY548815 | AY548816 | DQ883718 | DQ883715 | DQ883725 |

| 946 | Dothideomycetes | Botryosphaeriales | CBS 115476 | Botryosphaeria dothidea | DQ677998 | DQ678051 | FJ190612 | EU186063 | DQ677944 | DQ767637 |

| 1586 | Dothideomycetes | Botryosphaeriales | CBS 418.64 | Botryosphaeria tsugae | AF271127 | DQ767655 | DQ767644 | DQ677914 | ||

| 1618 | Dothideomycetes | Botryosphaeriales | CBS 237.48 | Guignardia bidwellii | DQ678034 | DQ678085 | DQ677983 | |||

| 1784 | Dothideomycetes | Botryosphaeriales | CBS 447.70 | Guignardia gaultheriae | DQ678089 | FJ190646 | DQ677987 | |||

| 939 | Dothideomycetes | Capnodiales | CBS 147.52 | Capnodium coffeae | DQ247808 | DQ247800 | FJ190609 | DQ471162 | DQ247788 | DQ471089 |

| 1289 | Dothideomycetes | Capnodiales | CBS 170.54 | Cladosporium cladosporioides | DQ678004 | DQ678057 | FJ190628 | EU186064 | DQ677952 | DQ677898 |

| 1591 | Dothideomycetes | Capnodiales | CBS 399.80 | Davidiella tassiana | DQ678022 | DQ678074 | DQ677971 | DQ677918 | ||

| 2021 | Dothideomycetes | Capnodiales | OSC 100622 | Mycosphaerella fijiensis | DQ767652 | DQ678098 | FJ190656 | DQ677993 | ||

| 1615 | Dothideomycetes | Capnodiales | CBS 292.38 | Mycosphaerella graminicola | DQ678033 | DQ678084 | DQ677982 | |||

| 942 | Dothideomycetes | Capnodiales | CBS 113265 | Mycosphaerella punctiformis | DQ471017 | DQ470968 | FJ190611 | DQ471165 | DQ470920 | DQ471092 |

| 1594 | Dothideomycetes | Capnodiales | CBS 325.33 | Scorias spongiosa | DQ678024 | DQ678075 | FJ190643 | DQ677973 | DQ677920 | |

| 274 | Dothideomycetes | Dothideales | DAOM 231303 | Dothidea sambuci | AY544722 | AY544681 | AY544739 | DQ522854 | DQ497606 | |

| 1359 | Dothideomycetes | Dothideales | CBS 737.71 | Dothiora cannabinae | DQ479933 | DQ470984 | FJ190636 | DQ471182 | DQ470936 | DQ471107 |

| 1300 | Dothideomycetes | Dothideales | CBS 116.29 | Sydowia polyspora | DQ678005 | DQ678058 | FJ190631 | DQ677953 | DQ677899 | |

| Dothideomycetes | Hysteriales | CBS 114601 | Gloniopsis smilacis | FJ161135 | FJ161174 | FJ161114 | FJ161091 | |||

| Dothideomycetes | Hysteriales | EB 0324 | Hysterium angustatum | FJ161167 | FJ161207 | FJ161129 | FJ161111 | |||

| Dothideomycetes | Hysteriales | EB 0249 | Hysterographium mori | FJ161155 | FJ161196 | FJ161104 | ||||

| 1613 | Dothideomycetes | Incertae sedis | CBS 283.51 | Helicomyces roseus | DQ678032 | DQ678083 | DQ677981 | DQ677928 | ||

| 1580 | Dothideomycetes | Incertae sedis | CBS 245.49 | Tubeufia paludosa | DQ767649 | DQ767654 | DQ767643 | DQ767638 | ||

| 1853 | Dothideomycetes | Myriangiales | CBS 150.27 | Elsinoë veneta | DQ767651 | DQ767658 | FJ190650 | DQ767641 | ||

| 1304 | Dothideomycetes | Myriangiales | CBS 260.36 | Myriangium duriaei | AY016347 | DQ678059 | AY571389 | DQ677954 | DQ677900 | |

| Dothideomycetes | Mytilinidiales | EB 0248 | Lophium mytilinum | FJ161163 | FJ161203 | FJ161128 | FJ161110 | |||

| Dothideomycetes | Mytilinidiales | CBS 301.34 | Mytilinidion australe | FJ161183 | ||||||

| Dothideomycetes | Mytilinidiales | CBS 135.34 | Mytilinidion rhenanum | FJ161136 | FJ161175 | FJ161115 | FJ161092 | |||

| 267 | Dothideomycetes | Pleosporales | DAOM 195275 | Allewia eureka | DQ677994 | DQ678044 | DQ677938 | DQ677883 | ||

| 1583 | Dothideomycetes | Pleosporales | CBS 126.54 | Ascochyta pisi var. pisi | DQ678018 | DQ678070 | DQ677967 | DQ677913 | ||

| 54 | Dothideomycetes | Pleosporales | CBS 134.39 | Cochliobolus heterostrophus | AY544727 | AY544645 | AY544737 | DQ247790 | DQ497603 | |

| 1599 | Dothideomycetes | Pleosporales | CBS 225.62 | Delitschia winteri | DQ678026 | DQ678077 | FJ190644 | DQ677975 | DQ677922 | |

| 1576 | Dothideomycetes | Pleosporales | CBS 101341 | Lepidosphaeria nicotiae | DQ678067 | DQ677963 | DQ677910 | |||

| 277 | Dothideomycetes | Pleosporales | DAOM 229267 | Leptosphaeria maculans | DQ470993 | DQ470946 | DQ471136 | DQ470894 | DQ471062 | |

| 1575 | Dothideomycetes | Pleosporales | CBS 276.37 | Phoma herbarum | DQ678014 | DQ678066 | FJ190640 | DQ677962 | DQ677909 | |

| 1600 | Dothideomycetes | Pleosporales | CBS 279.74 | Pleomassaria siparia | DQ678027 | DQ678078 | DQ677976 | DQ677923 | ||

| 940 | Dothideomycetes | Pleosporales | CBS 541.72 | Pleospora herbarum var. herbarum | DQ247812 | DQ247804 | FJ190610 | DQ471163 | DQ247794 | DQ471090 |

| 283 | Dothideomycetes | Pleosporales | DAOM 222769 | Pyrenophora phaeocomes | DQ499595 | DQ499596 | FJ190591 | DQ497614 | DQ497607 | |

| 1256 | Dothideomycetes | Pleosporales | CBS 524.50 | Sporormiella minima | DQ678003 | DQ678056 | FJ190624 | DQ677950 | DQ677897 | |

| 1598 | Dothideomycetes | Pleosporales | CBS 110020 | Ulospora bilgramii | DQ678025 | DQ678076 | DQ677974 | DQ677921 | ||

| 1601 | Dothideomycetes | Pleosporales | CBS 304.66 | Verruculina enalia | DQ678028 | DQ678079 | DQ677977 | DQ677924 | ||

| 1037 | Dothideomycetes | Pleosporales | CBS 454.72 | Westerdykella cylindrica | AY016355 | AY004343 | AF346430 | DQ471168 | DQ470925 | DQ497610 |

| 1063 | Eurotiomycetes | Chaetothyriales | CBS 175.95 | Ceramothyrium carniolicum | EF413627 | EF413628 | EF413629 | EF413630 | ||

| 1033 | Eurotiomycetes | Chaetothyriales | CBS190.61 | Cyphellophora laciniata | EF413618 | EF413619 | ||||

| 671 | Eurotiomycetes | Chaetothyriales | CBS 157.67 | Exophiala salmonis | EF413608 | EF413609 | FJ225745 | EF413610 | EF413611 | EF413612 |

| 1911 | Eurotiomycetes | Coryneliales | CBS 138.64 | Caliciopsis orientalis | DQ471039 | DQ470987 | FJ190654 | DQ471185 | DQ470939 | DQ471111 |

| 5007 | Eurotiomycetes | Eurotiales | CBS 658.74 | Aspergillus protuberus | FJ176842 | FJ176897 | FJ238379 | |||

| 2014 | Eurotiomycetes | Eurotiales | CBS 339.97 | Eupenicillium limosum | EF411061 | EF411064 | EF411068 | EF411070 | ||

| 1083 | Eurotiomycetes | Onygenales | GB | Ajellomyces capsulatum | Genome | Genome | Genome | Genome | Genome | |

| 1084 | Eurotiomycetes | Onygenales | TIGR | Coccidioides immitis | Genome | Genome | Genome | Genome | Genome | |

| 684 | Eurotiomycetes | Verrucariales | NYBG 808041 | Agonimia sp. | DQ782885 | DQ782913 | DQ782853 | DQ782874 | DQ782917 | |

| 697 | Eurotiomycetes | Verrucariales | DUKE 0047959 | Staurothele frustulenta | DQ823105 | DQ823098 | FJ225702 | DQ840553 | DQ840560 | |

| Geoglossomycetes | Geoglossales | OSC 60610 | Geoglossum glabrum | AY789316 | AY789317 | |||||

| 56 | Geoglossomycetes | Geoglossales | OSC 100009 | Geoglossum nigritum | AY544694 | AY544650 | AY544740 | DQ471115 | DQ470879 | DQ471044 |

| Geoglossomycetes | Geoglossales | Mycorec1840 | Geoglossum umbratile | AY789302 | AY789321 | |||||

| Geoglossomycetes | Geoglossales | HMAS 71956 | Sarcoleotia globosa 1 | AY789298 | AY789299 | |||||

| Geoglossomycetes | Geoglossales | OSC 63633 | Sarcoleotia globosa 2 | AY789409 | ||||||

| Geoglossomycetes | Geoglossales | MBH 52476 | Sarcoleotia globosa 3 | AY789428 | ||||||

| 64 | Geoglossomycetes | Geoglossales | OSC 100017 | Trichoglossum hirsutum 1 | AY544697 | AY544653 | AY544758 | DQ471119 | DQ470881 | DQ471049 |

| Geoglossomycetes | Geoglossales | OSC 61726 | Trichoglossum hirsutum 2 | AY789312 | AY789313 | |||||

| 229 | Incertae sedis | Incertae sedis | IAM 12963 | Saitoella complicata | AY548297 | AY548296 | DQ471133 | AY548300 | DQ471133 | |

| Laboulbeniomycetes | Laboulbeniales | GB | Hesperomyces virescens | AF298233 | AF298235 | |||||

| Laboulbeniomycetes | Laboulbeniales | GB | Stigmatomyces protrudens | AF298232 | AF298234 | |||||

| 2197 | Laboulbeniomycetes | Pyxidiophorales | CBS 657.82 | Pyxidiophora avernensis | FJ176839 | FJ176894 | FJ238377 | FJ238412 | ||

| 962 | Lecanoromycetes | Agyriales | GB | Trapelia placodioides | AF119500 | AF274103 | AF431962 | DQ366259 | DQ366260 | DQ366258 |

| 589 | Lecanoromycetes | Incertae sedis | DUKE 0047522 | Lecidea fuscoatra | DQ912310 | DQ912332 | DQ912275 | DQ912355 | DQ912381 | |

| 6 | Lecanoromycetes | Lecanorales | DUKE 0047740 | Canoparmelia caroliniana | AY584658 | AY584634 | AY584613 | DQ782817 | AY584683 | DQ782889 |

| 195 | Lecanoromycetes | Lecanorales | DUKE 0047550 | Hypogymnia physodes | DQ973006 | DQ973030 | DQ972978 | DQ973091 | ||

| 958 | Lecanoromycetes | Ostropales s.l. | Lumbsch 995 | Diploschistes ocellatus | AF038877 | AY605077 | DQ366252 | DQ366253 | DQ366251 | |

| 1349 | Lecanoromycetes | Ostropales s.l. | JK 5548K | Glomerobolus gelineus | DQ247811 | DQ247803 | DQ247784 | DQ247793 | ||

| 128 | Lecanoromycetes | Peltigerales | DUKE 0047503 | Lobaria scrobiculata | AY584679 | AY584655 | AY584621 | DQ883736 | DQ883749 | DQ883768 |

| 314 | Lecanoromycetes | Peltigerales | DUKE 0047520 | Lobariella pallida | DQ883788 | DQ883797 | DQ912297 | DQ883740 | DQ883753 | DQ883772 |

| 131 | Lecanoromycetes | Peltigerales | DUKE 0047548 | Nephroma parile | 46411421 | 46411445 | 46411390 | DQ973061 | DQ973075 | FJ772246 |

| 134 | Lecanoromycetes | Peltigerales | DUKE 0047504 | Peltigera degenii | AY584681 | AY584657 | AY584628 | DQ782826 | AY584688 | DQ782897 |

| 333 | Lecanoromycetes | Peltigerales | DUKE 0047747 | Coccocarpia erythroxyli | DQ883791 | DQ883800 | DQ912294 | DQ883743 | DQ883756 | DQ883775 |

| 875 | Lecanoromycetes | Pertusariales | DUKE 0047641 | Icmadophila ericetorum | DQ883704 | DQ883694 | DQ986897 | DQ883723 | DQ883711 | DQ883730 |

| 224 | Lecanoromycetes | Pertusariales | DUKE 0047506 | Pertusaria dactylina | DQ782880 | DQ782907 | DQ972973 | DQ782828 | DQ782868 | DQ782899 |

| 320 | Lecanoromycetes | Teloschistales | DUKE 0047507 | Heterodermia vulgaris | DQ883789 | DQ883798 | DQ912288 | DQ883741 | DQ883754 | DQ883773 |

| 686 | Lecanoromycetes | Teloschistales | DUKE 0047544 | Pyxine subcinerea | DQ883793 | DQ883802 | DQ912292 | DQ883745 | DQ883758 | DQ883777 |

| 87 | Lecanoromycetes | Teloschistales | DUKE 0047925 | Teloschistes exilis | AY584671 | AY584647 | FJ772245 | DQ883779 | DQ883759 | DQ883764 |

| 59 | Leotiomycetes | Helotiales | OSC 100012 | Botryotinia fuckeliana | AY544695 | AY544651 | AY544732 | DQ471116 | DQ247786 | DQ471045 |

| Leotiomycetes | Helotiales | MBH 52481 | Bryoglossum gracile | AY789419 | AY789420 | |||||

| 166 | Leotiomycetes | Helotiales | OSC 100054 | Cudoniella cf. clavus | DQ470992 | DQ470944 | FJ713604 | DQ471128 | DQ470888 | DQ471056 |

| 941 | Leotiomycetes | Helotiales | CBS 161.38 | Dermea acerina | DQ247809 | DQ247801 | DQ976373 | DQ471164 | DQ247791 | DQ471091 |

| 49 | Leotiomycetes | Helotiales | OSC 100002 | Lachnum virgineum | AY544688 | AY544646 | AY544745 | DQ842030 | DQ470877 | DQ497602 |

| 1262 | Leotiomycetes | Helotiales | CBS 811.85 | Lambertella subrenispora | DQ471030 | DQ470978 | DQ471176 | DQ470930 | DQ471101 | |

| 1 | Leotiomycetes | Helotiales | OSC 100001 | Leotia lubrica | AY544687 | AY544644 | AY544746 | DQ471113 | DQ470876 | DQ471041 |

| Leotiomycetes | Helotiales | FH-DSH -97103 | Microglossum olivaceum | AY789396 | AY789397 | |||||

| Leotiomycetes | Helotiales | Ingo-Clark-Geo163 | Microglossum rufum 1 | DQ257358 | DQ257359 | |||||

| 1292 | Leotiomycetes | Helotiales | OSC 100641 | Microglossum rufum 2 | DQ471033 | DQ470981 | DQ471179 | DQ470933 | DQ471104 | |

| Leotiomycetes | Helotiales | ZW02-012 | Mitrula brevispora | AY789292 | AY789293 | |||||

| Leotiomycetes | Helotiales | WZ-Geo47-Clark | Mitrula elegans | AY789334 | AY789335 | |||||

| 169 | Leotiomycetes | Helotiales | OSC 100063 | Monilinia laxa | AY544714 | AY544670 | AY544748 | FJ238425 | DQ470889 | DQ471057 |

| 1259 | Leotiomycetes | Helotiales | CBS 477.97 | Neobulgaria pura | FJ176865 | FJ238434 | FJ238350 | FJ238397 | ||

| 149 | Leotiomycetes | Helotiales | OSC 100036 | Neofabraea malicorticis | AY544706 | AY544662 | AY544751 | DQ471124 | DQ470885 | DQ847414 |

| Leotiomycetes | Helotiales | 1100803 | Thueminidium atropurpureum 1 | AY789307 | ||||||

| Leotiomycetes | Helotiales | 1136126 | Thueminidium atropurpureum 2 | AY789305 | ||||||

| 353 | Leotiomycetes | Rhytismatales | DUKE 0047585 | Cudonia circinans | AF107343 | AY533013 | AY584700 | AY641033 | ||

| Leotiomycetes | Rhytismatales | OSC 100640 | Spathularia velutipes 1 | FJ997860 | FJ997861 | FJ997863 | FJ997862 | |||

| Leotiomycetes | Rhytismatales | ZW Geo58 | Spathularia velutipes 2 | AY789356 | AY789357 | |||||

| 896 | Lichinomycetes | Lichinales | Schultz16319a | Lichinella iodopulchra | DQ782857 | DQ832328 | DQ832327 | |||

| 892 | Lichinomycetes | Lichinales | DUKE 0047648 | Peltula auriculata | DQ832332 | DQ832330 | DQ782856 | DQ832331 | ||

| 891 | Lichinomycetes | Lichinales | DUKE 0047527 | Peltula umbilicata | DQ782887 | DQ832334 | DQ922954 | DQ782855 | DQ832335 | DQ782919 |

| 1363 | Neolectomycetes | Neolectales | DAH-3 | Neolecta irregularis | DQ842040 | DQ470986 | DQ471109 | |||

| 1362 | Neolectomycetes | Neolectales | DAH-11 | Neolecta vitellina | DQ471037 | DQ470985 | AAF19058 | |||

| 1252 | Orbiliomycetes | Orbiliales | CBS 397.93 | Arthrobotrys elegans | FJ176810 | FJ176864 | FJ238349 | FJ238395 | ||

| 905 | Orbiliomycetes | Orbiliales | CBS 917.72 | Orbilia vinosa | DQ471000 | DQ470952 | DQ471145 | DQ471071 | ||

| 65 | Pezizomycetes | Pezizales | OSC 100018 | Aleuria aurantia | AY544698 | AY544654 | DQ471120 | DQ247785 | DQ466085 | |

| 70 | Pezizomycetes | Pezizales | KH-00-08 | Ascobolus carbonarius | AY544720 | AY544677 | FJ238423 | |||

| 152 | Pezizomycetes | Pezizales | OSC 100062 | Caloscypha fulgens | DQ247807 | DQ247799 | DQ471126 | DQ247787 | DQ471054 | |

| 933 | Pezizomycetes | Pezizales | CBS 626.71 | Eleutherascus lectardii | DQ471014 | DQ470966 | FJ190606 | DQ471160 | DQ470918 | DQ471088 |

| 176 | Pezizomycetes | Pezizales | OSC 100068 | Gyromitra californica | AY544717 | AY544673 | AY544741 | DQ471130 | DQ470891 | DQ471059 |

| 507 | Pezizomycetes | Pezizales | TL-6398 | Peziza vesiculosa | DQ470995 | DQ470948 | DQ471140 | DQ470898 | DQ471066 | |

| 949 | Pezizomycetes | Pezizales | CBS 666.88 | Pyronema domesticum | DQ247813 | DQ247805 | FJ190613 | DQ471166 | DQ247795 | DQ471093 |

| 1299 | Pezizomycetes | Pezizales | CBS 472.80 | Saccobolus dilutellus | FJ176814 | FJ176870 | FJ238436 | FJ238353 | FJ238402 | |

| 954 | Pezizomycetes | Pezizales | CBS 733.68 | Sarcosoma latahense | FJ176806 | FJ176860 | FJ238424 | FJ238392 | ||

| 153 | Pezizomycetes | Pezizales | OSC 100049 | Sarcosphaera crassa | AY544712 | AY544668 | FJ238430 | |||

| 62 | Pezizomycetes | Pezizales | OSC 100015 | Scutellinia scutellata | DQ247814 | DQ247806 | FJ190587 | DQ479935 | DQ247796 | DQ471047 |

| 74 | Pezizomycetes | Pezizales | NRRL 22338 | Verpa conica | AY544710 | AY544666 | AY544761 | FJ238389 | ||

| 1073 | Saccharomycetes | Saccharomycetales | GB | Candida glabrata | AY198398 | AY198398 | XM_447415 | XM_448959 | Genome | |

| 1269 | Saccharomycetes | Saccharomycetales | GB | Candida tropicalis | M55527 | Genome | Genome | Genome | Genome | |

| 1077 | Saccharomycetes | Saccharomycetales | GB | Debaryomyces hansenii | DHA508273 | AF485980 | XM_456921 | CR382139 | Genome | |

| 1072 | Saccharomycetes | Saccharomycetales | GB | Eremothecium gossypii | AE016820 | AE016820 | AF442353 | NM_209535 | AE016819 | Genome |

| 1069 | Saccharomycetes | Saccharomycetales | GB | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | SCYLR154C | SCYLR154C | AF442281 | X96876 | SCYOR151C | Genome |

| 1199 | Schizosaccharomycetes | Schizosaccharomycetales | GB | Schizosaccharomyces pombe | X54866 | Z19136 | X54421 | X56564 | D13337 | Genome |

| 5086 | Sordariomycetes | Calosphaeriales | CBS 115999 | Calosphaeria pulchella | AY761071 | AY761075 | FJ238421 | |||

| Sordariomycetes | Coronophorales | SMH4320 | Bertia moriformis | AY695260 | AY780151 | |||||

| 2124 | Sordariomycetes | Diaporthales | CBS 171.69 | Cryptosporella hypodermia | DQ862049 | DQ862028 | DQ862018 | DQ862034 | ||

| 935 | Sordariomycetes | Diaporthales | CBS 109767 | Diaporthe eres | DQ471015 | AF408350 | FJ190607 | DQ471161 | DQ470919 | DQ479931 |

| 1223 | Sordariomycetes | Diaporthales | CBS 112915 | Endothia gyrosa | DQ471023 | DQ470972 | DQ471169 | DQ470926 | DQ471096 | |

| 952 | Sordariomycetes | Diaporthales | CBS 199.53 | Gnomonia gnomon | DQ471019 | AF408361 | FJ190615 | DQ471167 | DQ470922 | DQ471094 |

| 187 | Sordariomycetes | Hypocreales | GJS 71-328 | Bionectria cf. aureofulva | DQ862044 | DQ862027 | FJ713625 | DQ862013 | DQ862029 | |

| 189 | Sordariomycetes | Hypocreales | GAM 12885 | Claviceps purpurea | AF543765 | AF543789 | AY489648 | DQ522417 | AF543778 | |

| 162 | Sordariomycetes | Hypocreales | OSC 93609 | Cordyceps cardinalis | AY184973 | AY184962 | EF469007 | DQ522370 | DQ522422 | DQ522325 |

| 192 | Sordariomycetes | Hypocreales | OSC 71233 | Elaphocordyceps capitata | AY489689 | AY489721 | FJ713628 | AY489649 | DQ522421 | AY489615 |

| 193 | Sordariomycetes | Hypocreales | OSC 106405 | Elaphocordyceps ophioglossoides | AY489691 | AY489723 | FJ713629 | AY489652 | DQ522429 | AY489618 |

| 163 | Sordariomycetes | Hypocreales | ATCC 56429 | Epichloë typhina | U32405 | U17396 | FJ713624 | DQ522440 | AF543777 | |

| 156 | Sordariomycetes | Hypocreales | ATCC 208838 | Hypocrea lutea | AF543768 | AF543791 | FJ713620 | AY489662 | DQ522446 | AF543781 |

| 159 | Sordariomycetes | Hypocreales | CBS 114055 | Nectria cinnabarina | U32412 | U00748 | FJ713622 | AY489666 | DQ522456 | AF543785 |

| 1265 | Sordariomycetes | Incertae sedis | FAU 553 | Glomerella cingulata | AF543762 | AF543786 | FJ190626 | AY489659 | DQ522441 | AF543773 |

| 237 | Sordariomycetes | Incertae sedis | ATCC 16535 | Verticillium dahliae | AY489705 | DQ470945 | FJ713630 | AY489673 | DQ522468 | AY489632 |

| 413 | Sordariomycetes | Lulworthiales | JK 5090A | Lindra thalassiae | DQ470994 | DQ470947 | FJ190593 | DQ471139 | DQ470897 | DQ471065 |

| 747 | Sordariomycetes | Lulworthiales | JK 4686 | Lulworthia grandispora | DQ522855 | DQ522856 | FJ190595 | DQ518181 | DQ497608 | |

| 734 | Sordariomycetes | Magnaporthales | JK 5528S | Gaeumannomyces medullaris | FJ176801 | FJ176854 | ||||

| 1081 | Sordariomycetes | Magnaporthales | Broad | Magnaporthe grisea | AB026819 | AB026819 | Genome | Genome | Genome | |

| Sordariomycetes | Melanosporales | ATCC 15515 | Melanospora tiffanyae | AY015619 | AY015630 | AY015637 | ||||

| 1906 | Sordariomycetes | Microascales | TCH C89 | Ceratocystis fimbriata | U32418 | U17401 | FJ238372 | |||

| 5011 | Sordariomycetes | Microascales | 728a | Corollospora maritima | FJ176846 | FJ176901 | FJ190660 | FJ238381 | FJ238415 | |

| 1907 | Sordariomycetes | Microascales | CBS 122611 | Gondwanamyces capensis | FJ176834 | FJ176888 | FJ238373 | |||

| 409 | Sordariomycetes | Microascales | CBS 197.60 | Halosphaeria appendiculata | U46872 | U46885 | FJ238390 | |||

| 1038 | Sordariomycetes | Ophiostomatales | CBS 139.51 | Ophiostoma stenoceras | DQ836897 | DQ836904 | FJ190618 | DQ836891 | DQ836912 | |

| 1078 | Sordariomycetes | Sordariales | Broad | Neurospora crassa | X04971 | AF286411 | XM_959004 | XM_324476 | Genome | |

| 216 | Sordariomycetes | Sordariales | CBSC 15-5973 | Sordaria fimicola | AY545728 | AY545724 | DQ518175 | |||

| 51 | Sordariomycetes | Xylariales | OSC 100004 | Xylaria hypoxylon | AY544692 | AY544648 | AY544760 | DQ471114 | DQ470878 | DQ471042 |

| 1234 | Taphrinomycetes | Taphrinales | CBS 356.35 | Taphrina deformans | DQ471024 | DQ470973 | FJ713610 | DQ471170 | DQ470927 | DQ471097 |

| 265 | Taphrinomycetes | Taphrinales | IAM 14515 | Taphrina wiesneri | AY548293 | AY548292 | AY548291 | DQ471134 | AY548298 | DQ471134 |

1voucher GB = obtained from GenBank, or genome databases without clear voucher numbers.

The phylogenetic analysis was run in RAxML v7.0.0 (Stamatakis 2006), partitioning by gene (six partitions) and estimating unique model parameters for each gene, as in Schoch et al. (2009). Models of evolution were evaluated as in Schoch et al. (2009) with the same models selected. For DNA sequences, this resulted in a general time reversible model (GTR) with a discrete gamma distribution composed of four rate classes plus an estimation of the proportion of invariable sites. The amino acid sequences were analysed with a RTREV model with similar accommodation of rate heterogeneity across sites and proportions of invariant sites. In addition, protein models for TEF1 and RPB2 incorporated a parameter to estimate amino acid frequencies. The tree shown in Fig. 1 was obtained by using an option in RAxML running a rapid bootstrap analysis and search for the best-scoring ML tree in one single run. This meant the GTRCAT model approximation was used, which does not produce likelihood values comparable to other programs. The full tree is shown here as Fig. 2 and was deposited in TreeBASE (www.treebase.org). We also ran 100 repetitions of RAxML under a gamma rate distribution option. The best scoring tree was included in TreeBASE.

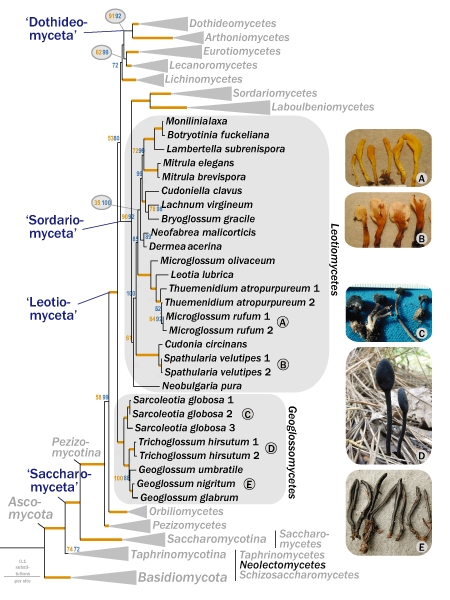

Fig. 2.

A most likely tree obtained by RAxML for Ascomycota (as in Fig. 1). Phyla, subphyla, class, order and rankless taxa are indicated. Taxa designated as earth tongues are indicated in orange. The tree is displayed as two subtrees – orange arrows indicate where the subtrees were joined. The tree was rooted with outgroup Rhizopus oryzae (not shown). Bootstrap values are shown in orange above nodes and Bayesian posterior probabilities in blue below. Numbers were removed for nodes with 100 % bootstrap and 100 % posterior probability.

A second analysis was run using Bayesian inference of maximum likelihood in MrBayes v3.1.2 (Huelsenbeck & Ronquist 2001, Altekar et al. 2004) using models and parameters that were comparable to the maximum likelihood run. Data were similarly partitioned and amino acids were analysed, so that a mixture of models with fixed rate matrices for amino acid sequences could be evaluated. In all cases rate heterogeneity parameters were used by a discrete gamma distribution plus an estimation of the proportion of invariable sites. A metropolis coupled Markov Chain Monte Carlo analysis was run for 9 million generations sampling every 200th cycle, starting from a random tree and using 4 chains (three heated and one cold) under default settings. Two separate runs were confirmed to converge using Tracer v1.4.1 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/tracer/). The first 10 000 sampled trees (2 million generations) were removed as burn in each run. A 50 % majority rule consensus tree of 70 000 Bayesian likelihood trees from the two combined runs was subsequently constructed, and average branch lengths and posterior probabilities determined. The numbers of nodes shared with the most likely tree in Fig. 1 was determined and plotted on the branches. This tree was deposited in TreeBASE, along with the inclusive character set.

RESULTS

The phylogeny presented in Fig. 1 supports 15 classes (11 in Pezizomycotina, 1 in Saccharomycotina, 3 in Taphrinomycotina) with good statistical support (both ML bootstrap and Bayesian posterior probability) for 14. Phylogenies with all lineages in the analysed data matrix are included in Fig. 2. A run with 100 repetitions of RAxML under a gamma rate distribution option resulted in a best scoring tree with a log likelihood of -111983. This tree shared the same supported nodes with the one presented in Fig. 1 but had changes in poorly supported nodes regarding placement of the Eurotiomycetes and Dothideomycetes. The two Bayesian runs produced trees with harmonic means of likelihood values of -112094 and -112076, respectively, with similar topological differences in poorly supported nodes.

As can be seen in Fig. 1, we continue to find low bootstrap and posterior probability support for Leotiomycetes as a monophyletic clade using a combined analysis of protein and nucleic acids. In our analysis, this includes Neobulgaria pura as the earliest diverging lineage. The node internal from this lineage is found in all ML bootstrap trees, suggesting that this taxon is unstable in our analyses. No conflicts were detected in Neobulgaria genes under a previous study and missing data did not affect important nodes (Schoch et al. 2009). A repeat run under maximum likelihood was done with Neobulgaria pura removed under the same settings but with only 100 bootstrap repetitions. This trimmed dataset yielded a congruent phylogeny with increased bootstrap for Leotiomycetes (78 %; data not shown). The instability of the placement of Neobulgaria pura does not compromise any of the conclusions we present here and may be due to various reasons. Improved taxon sampling will likely help to resolve its placement in future analyses.

We find support for numerous backbone nodes in Ascomycota, as did Schoch et al. (2009). Our phylum-wide sampling of Ascomycota classes in this study, combined with the results of a previous study (Schoch et al. 2009), facilitated addressing the placement of the previously problematic and unsampled lineages such as the Geoglossaceae in relation to all currently accepted Ascomycota classes.

Taxonomy

Given their unique ascomatal development, ultrastructure of ascus apical apparatus, mossy habitat, and our multilocus gene phylogeny, Geoglossomycetes cl. & ord. nov. is justified here as incertae sedis in Pezizomycotina and ‘Leotiomyceta’.

Geoglossomycetes, Geoglossales Zheng Wang, C.L. Schoch & Spatafora, cl. & ord. nov. — MycoBank MB513351, MB513352

Ascomata solitaria vel gregaria, capitata, stipitata; stipe cylindricus, atrum, glabrum vel furfuraceus. Regio hymeniali capitata, clavata vel pileata, indistinctum ex stipite; hymenium atrum, continuatcum stipite ad praematuro incrementi grado. Asci clavati, inoperculati, octospori, poro parvo in iodo caerulescentes. Ascosporae elongatae, fuscae, pullae vel hyalinae, multiseptatae. Paraphyses filiformes, pullae vel hyalinae. Distributio generalis, terrestris, habitaile locus fere uliginoso et muscoso.

Type genus. Geoglossum Pers., Neues Mag. Bot. 1: 116. 1794; Geoglossaceae.

Ascomata scattered to gregarious, capitate, stipitate; stipe cylindrical, black, smooth to furfuraceous. Ascigerous portion capitate, club-shaped to pileate, indistinguishable from stipe. Hymenium surface black, continues with stipe at early development stage. Asci clavate, inoperculate, thin-walled, J+, usually 8-spored. Ascospores elongate, dark-brown, blackish to hyaline, septate when mature. Paraphyses filiform, blackish to hyaline. Global distribution, terrestrial, habitat usually boggy and mossy.

DISCUSSION

In keeping with the phylogeny presented in Fig. 1, we endorse use of the -myceta suffix in order to circumscribe well-supported clades above class. The numbers of these clades are limited, and the use of such taxa will continue to become more practical as our biological knowledge base broadens. Use of this suffix will also allow for the continued use of Leotiomyceta, a taxon that has already been defined with a Latin diagnosis provided as a ranked superclass (Eriksson & Winka 1997) and remains in use (Lumbsch et al. 2005, Wang et al. 2006a). We propose its continued use, but as a rankless taxon together with the newly proposed rankless taxa, ‘Saccharomyceta’, ‘Dothideomyceta’ and ‘Sordariomyceta’. Since these taxa are not currently accepted under the Code (McNeill et al. 2006), we will refrain from formal designations. The relevant clades are discussed below with the informal designations indicated in single quotations.

Subphylum Taphrinomycotina

As in recent studies using large multi-gene datasets (Spatafora et al. 2006, Sugiyama et al. 2006, Liu et al. 2009, Schoch et al. 2009), we find ML bootstrap support here for the monophyly of the Taphrinomycotina. The addition of sequences from protein coding genes has been vital to the establishment of statistical support for this grouping. Recent work has shown that the short generation times characteristic of species in this group make phylogenetic analyses particularly susceptible to long branch attraction artefacts (Liu et al. 2009). The placement of Neolecta in this subclade is also confirmed here. The club-shaped apothecia of the members of Neolecta share superficial similarity with those of the Geoglossaceae. Neolecta was long thought to be included in the Geoglossaceae until molecular work proved otherwise (Landvik 1996). In support of its placement in this early diverging group, Neolecta has several presumably ancestral features, such as simplified non-poricidal asci without croziers and the absence of paraphyses (Redhead 1979, Landvik et al. 2003). With additional sampling of both taxa and genes we find here moderate support for the monophyly of Taphrinomycotina, and thus demonstrate that the earliest diverging clade of the Ascomycota was dimorphic, with both filamentous and yeast growth forms. Nevertheless, it remains apparent that this part of the Ascomycota tree remains under sampled. This lack of adequate sampling is supported by the recent description of a clade labelled ‘Soil Clone Group I’ (SCGI). SCGI is ubiquitous in soil and is only known from environmental sequence data (Porter et al. 2008). It appears possible that they form a novel early diverging lineage outside of Taphrinomycotina. Very little remains known about their ecology, morphology and general biology.

Rankless taxon ‘Saccharomyceta’

‘Saccharomyceta’ includes the two remaining subphyla of Ascomycota, Saccharomycotina and Pezizomycotina. Saccharomycotina comprises the ‘true yeasts’ (e.g., Saccharomyces cerevisiae), although hyphal growth has been documented in some taxa (e.g., Eremothecium). The Pezizomycotina consists of the majority of filamentous, ascoma producing species, but numerous species are additionally capable of yeast and yeast-like growth phases. Thousands of species are only known to reproduce asexually. These two subphyla form a well-supported, monophyletic group that has been recovered in a large number of studies across a diversity of character and taxon sets. The recognition of ‘Saccharomyceta’ highlights the shared common ancestry of these two taxa and the inaccurate characterisation of Saccharomycotina as a primitive or basal lineage of the Ascomycota. Rather, its small genome size (Dujon et al. 2004) and dominant yeast growth phase can be characterized as derived traits for this subphylum.

Rankless taxon ‘Leotiomyceta’

We apply ‘Leotiomyceta’ as a rankless taxon containing the majority of fungi with a diversity of inoperculate asci (e.g., fissitunicate, poricidal, deliquescent). ‘Leotiomyceta’ excludes the earliest diverging classes of Pezizomycotina, Pezizomycetes and Orbiliomycetes. It was first defined as a superclass (Eriksson & Winka 1997). This definition has remained in use (Lumbsch et al. 2005, Spatafora et al. 2006). Included in this clade are the informal, rankless taxa ‘Dothideomyceta’, ‘Sordariomyceta’, as well as the classes Eurotiomycetes, Lecanoromycetes, Lichinomycetes, and a newly proposed class, Geoglossomycetes.

The type genus of Geoglossaceae, Geoglossum was initially proposed by Persoon (1794). Persoon described it as club-shaped, with unitunicate, inoperculate asci, with the type species given as Geoglossum glabrum Pers. Trichoglossum have historically been classified in Geoglossaceae, and Sarcoleotia has historically been classified in the Helotiaceae (Leotiomycetes). These inoperculate Discomycetes produce terrestrial, stipitate, clavate ascomata, commonly referred to as earth tongues, which include Leotia, Microglossum, Cudonia, and Spathularia. In terms of ascomatal development, species of Geoglossum, Trichoglossum, and Sarcoleotia possess a hymenium that freely develops towards the base, while other earth tongue fungi feature a distinct ridge to their hymenium, implying a developmental stage during which the hymenium is enclosed (Schumacher & Sivertsen 1987, Spooner 1987, Wang et al. 2006b). An enclosed hymenium has been observed as well in several other lineages, such as Cyttaria, Erysiphales and Rhytismatales in the Leotiomycetes (Korf 1983, Gargas et al. 1995, Johnston 2001). Although the name earth tongue implies these fungi are terrestrial and have no direct association found with other organisms, Trichoglossum, Geoglossum and Sarcoleotia globosa have often been recorded in boggy habitats abundant with bryophytes (Seaver 1951, Dennis 1968, Schumacher & Sivertsen 1987, Spooner 1987, Jumpponen et al. 1997, Zhuang 1998). Ascus apical morphology is one of the major features in distinguishing higher ascomycetes, and operculate ascomycetes as members of Pezizales have an apical or subapical operculum which is thrown back at spore discharge while a definite plug is present in the thickened ‘inoperculate’ ascus apex as in species of the Helotiales (Korf 1973). Ultrastructure of the ascus apical apparatus suggested no close relationship between Leotia lubrica and species of Geoglossum and Trichoglossum. A structure known as a tractus connects the uppermost spore to the apical wall and the spores to each other in Trichoglossum hirsutum, but is never found in other species of the Helotiales and is possibly homologous to structures in Sordariomycetes and Pezizomycetes (Verkley 1994). Recent molecular phylogenetic analyses (Sandnes 2006, Wang et al. 2006a, b) confirmed that the earth tongue fungi are not monophyletic. At least two origins occurred in Leotiomycetes: in Leotia and allies in Helotiales, and in Cudonia and allies in Rhytismatales. Geoglossum, Trichoglossum. Sarcoleotia (Geoglossomycetes as we define it) represent a third, independent lineage of earth tongues, which we confirmed does not belong within the Leotiomycetes.

DNA-only and combined model analyses produced conflicting placements of Geoglossaceae within Pezizomycotina. Previous analyses applying nucleotide sequences only placed the order as a sister group to the Lichinomycetes (Lutzoni et al. 2004, Spatafora et al. 2006), which includes a small number of lichenised species mainly associated with cyanobacteria (Reeb et al. 2004). Our sampling of Lichinomycetes includes two genera, Peltula and Lichinella that encompass at least some of the ascal diversity, i.e., rostrate and deliquescent, present in the class. In contrast, our combined amino acid and nucleotide model analyses resolved Geoglossaceae as an isolated, unique lineage of ‘Leotiomyceta’ with no supported sister relationship, in agreement with Schoch et al. (2009). Different levels of missing data underlie these two conflicting topologies, and several phenomena can potentially explain this conflict, ranging from model misspecification to long-branch attraction. Regardless of these concerns, our conclusion that the Geoglossaceae is a monophyletic lineage, unallied with members of the Leotiomycetes and any of the other large fungal classes remains strongly supported.

Eurotiomycetes and Lecanoromycetes are the two remaining classes in ‘Leotiomyceta’. Eurotiomycetes is arguably the most ecologically diverse class within Ascomycota including lichenised species, saprobes and pathogens of animals and plants. As currently defined, this class incorporates several distinct orders and three subclasses spanning virtually all known fungal ecological niches (Geiser et al. 2006). Lecanoromycetes contain the majority of the lichenised fungi (Miadlikowska et al. 2006). Earlier large-scale phylogenies (e.g. Lutzoni et al. 2004) have suggested a sister relationship between these two classes, but we find that such a relationship remains without strong statistical support (Fig. 1). Despite this, internal nodes are well supported enough to provide good support for the hypothesis that lichenisation evolved multiple times in the Ascomycota, with losses being rare (Gueidan et al. 2008, Schoch et al. 2009).

The remaining classes are discussed in relation to their respective rankless taxa listed below.

Rankless taxon ‘Dothideomyceta’

This taxon is well supported, with ML bootstrap of 91 % and a moderate Bayesian posterior probability of 92 %. It includes two classes of fungi which produce fissitunicate asci, Arthoniomycetes and Dothideomycetes. Arthoniomycetes consists of ± 1 600 species of lichenised and lichenicolous fungi with fissitunicate asci and exposed hymenia (Grube 1998, Ertz et al. 2009). Unlike other species with fissitunicate asci, these taxa have ascohymenial development, prompting their placement in a transitory group, or ‘Zwischengruppe’ that is intermediate between ascohymenial and ascolocular development (Henssen & Jahns 1974). The class is resolved as sister to Dothideomycetes, consistent with recent studies (Lutzoni et al. 2004, Spatafora et al. 2006, Wang et al. 2006a). Dothideomycetes is a large class containing two subclasses, Dothideomycetidae and Pleosporomycetidae (Schoch et al. 2006). Our analysis contains members of all known orders in the class, including recent additions (Boehm et al. 2009). This broad representation yields increased resolution in the placement of an order previously labelled incertae sedis, Botryosphaeriales (Schoch et al. 2006). Placement of Botryosphaeriales within subclass Pleosporomycetidae is well supported, as is a close relationship with the unplaced family Tubeufiaceae (Fig. 2).

Rankless taxon ‘Sordariomyceta’

‘Sordariomyceta’ contains three classes, Leotiomycetes, Laboulbeniomycetes and Sordariomycetes. We find similar resolution for this clade as for the ‘Dothideomyceta’. These three classes are characterised by the production of unitunicate, poricidal asci, or derivatives of such asci (e.g., deliquescent asci). Leotiomycetes and Sordariomycetes include numerous fungi associated with plants as pathogens, endophytes and epiphytes. The sordariomycete phylogeny is comparatively well resolved with 15 orders and 3 subclasses named (Zhang et al. 2006, Kirk et al. 2008). In contrast, the leotiomycete classification still poorly matches its inferred phylogeny. A recent class-wide effort to assess morphological and ecological data in a phylogenetic context continued to find high levels of diversity unaccounted for in the current classification (Wang et al. 2009). In addition to the aforementioned two classes, Fig. 1 also supports the placement of the Laboulbeniomycetes reported in Schoch et al. (2009) as part of a monophyletic lineage. The relationship between the Sordariomycetes and Laboulbeniomycetes is also well supported but we will refrain from naming this node until sampling can be expanded for the Laboulbeniomycetes. The class Laboulbeniomycetes encompasses an enigmatic lineage of insect symbionts and mycoparasites that have long proved problematic with respect to placement in higher-level classification schemes. Laboulbeniomycetes comprises two orders, Laboulbeniales and Pyxidiophorales, that are united by an ascospore synapomorphy of a darkened holdfast region and by molecular data (Weir & Blackwell 2001, 2005). Members of Pyxidiophorales possess globose perithecia with a single layer of wall cells, and long perithecial necks that release their ascospores passively in droplets at the tips of their necks; this mechanism is repeatedly derived within Ascomycota for insect dispersal of ascospores (Blackwell 1994). For this reason, they have been likened to other insect-dispersed perithecial ascomycetes (e.g., Ophiostomatales) that now are strongly supported as members of Sordariomycetes. Laboulbeniales includes ectoparasites of insects and displays morphological traits not found elsewhere in the Ascomycota. They form apomorphic ascomata produced by the division and enlargement of ascospores that are difficult to characterize in existing ascomatal terms. Laboulbeniales feature an ostiole, however, which is consistent with perithecia produced by hyphal growth. Determinate growth of the ascospore with a series of predictable cell divisions produces a thallus of a finite number of cells that is characteristic at the genus and species level (Tavares 1979). The analyses presented here strongly support Laboulbeniomycetes as sister to Sordariomycetes. This placement corresponds with the terminology originally applied to this group (Thaxter 1896). It is interesting to note that while species of Pyxidiophorales are endowed with a diverse group of anamorphs, members of Laboulbeniales are mainly known to reproduce sexually.

Summary

In conclusion, we propose two monotypic formal taxa and describe continued support for four informal rankless taxa. Important improvements in the resolution of deep nodes within the Ascomycota may be attributed to multi-gene sequence data produced by AFTOL and other projects during the last 5 years. The accelerating accumulation of genome-scale sequence data will continue to challenge and improve existing phylogenetic hypotheses. However, in order to direct limited resources towards under-sampled areas in the fungal phylogeny, an accurate, up-to-date classification is required. By placing three earth tongue genera in a separate newly described class, we underscore and communicate the genetic diversity that is found in the fungi producing these very convergent morphologies.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Kentaro Hosaka, Dan Luoma and Zhuliang Yang for the photographs used. We acknowledge funding provided by NSF through a grant (DEB 0717476) to J.W.S. and C.L.S. (while at Oregon State). C.L.S. was also supported in part by the Intramural Research program of the National Institutes of Health. Z.W. was supported by the Yale University Anonymous Postdoctoral Fellowship.

REFERENCES

- Altekar G, Dwarkadas S, Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. 2004. Parallel Metropolis coupled Markov chain Monte Carlo for Bayesian phylogenetic inference. Bioinformatics 20: 407 – 415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell M. 1994. Minute mycological mysteries: the influence of Arthropods on the lives of Fungi. Mycologia 86: 1 – 17 [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell M, Hibbett DS, Taylor JW, Spatafora JW. 2006. Research Coordination Networks: a phylogeny for kingdom Fungi (Deep Hypha). Mycologia 98: 829 – 837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm EWA, Schoch CL, Spatafora JW. 2009. On the evolution of the Hysteriaceae and Mytilinidiaceae (Pleosporomycetidae, Dothideomycetes, Ascomycota) using four nuclear genes. Mycological Research 113: 461 – 479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corda ACJ. 1838. Abbildungen der Pilze und Schwaemme. Icones Fungorum, Hucusque Cognitorum 2: 1 – 43 [Google Scholar]

- Dennis RWG. 1968. British ascomycetes Cramer Verlag, Lehre, Germany: [Google Scholar]

- Dujon B, Sherman D, Fischer G, Durrens P, Casaregola S, et al. 2004. Genome evolution in yeasts. Nature 430: 35 – 44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson OE, Winka K. 1997. Supraordinal taxa of Ascomycota. Myconet 1: 1 – 16 [Google Scholar]

- Ertz D, Miadlikowska J, Lutzoni F, Dessein S, Raspe O, et al. 2009. Towards a new classification of the Arthoniales (Ascomycota) based on a three-gene phylogeny focussing on the genus Opegrapha. Mycological Research 113: 141 – 152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gargas A, DePriest PT, Grube M, Tehler A. 1995. Multiple origins of lichen symbioses in Fungi suggested by SSU rDNA phylogeny. Science 268: 1492 – 1495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiser DM, Gueidan C, Miadlikowska J, Lutzoni F, Kauff F, et al. 2006. Eurotiomycetes: Eurotiomycetidae and Chaetothyriomycetidae. Mycologia 98: 1053 – 1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gernandt DS, Platt JL, Stone JK, Spatafora JW, Holst-Jensen A, et al. 2001. Phylogenetics of Helotiales and Rhytismatales based on partial small subunit nuclear ribosomal DNA sequences. Mycologia 93: 915 – 933 [Google Scholar]

- Grube M. 1998. Classification and phylogeny in the Arthoniales (Lichenized Ascomycetes). The Bryologist 101: 377 – 391 [Google Scholar]

- Gueidan C, Ruibal CV, Hoog GS de, Gorbushina AA, Untereiner WA, Lutzoni F. 2008. An extremotolerant rock-inhabiting ancestor for mutualistic and pathogen-rich fungal lineages. Studies in Mycology 62: 111 – 119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henssen A, Jahns HM. 1974. Lichenes Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart: [Google Scholar]

- Hibbett DS, Binder M, Bischoff JF, Blackwell M, Cannon PF, et al. 2007. A higher-level phylogenetic classification of the Fungi. Mycological Research 111: 509 – 547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbett DS, Donoghue MJ. 1998. Integrating phylogenetic analysis and classification in Fungi. Mycologia 90: 347 – 356 [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. 2001. MrBayes: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 17: 754 – 755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James TY, Kauff F, Schoch CL, Matheny PB, Hofstetter V, et al. 2006. Reconstructing the early evolution of Fungi using a six-gene phylogeny. Nature 443: 818 – 822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston PR. 2001. Monograph of the monocotyledon-inhabiting species of Lophodermium. Mycological Papers 176: 1 – 239 [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen PM. 2002. Rankless names in the Code?. Taxon 53: 162 [Google Scholar]

- Jumpponen A, Weber NS, Trappe JM, Cazares E. 1997. Distribution and ecology of the ascomycete Sarcoleotia globosa in the United States. Canadian Journal of Botany 75: 2228 – 2231 [Google Scholar]

- Kirk PM, Cannon PF, Minter DW, Stalpers JA. 2008. Ainsworth and Bisby’s dictionary of the Fungi CAB International, Wallingford, UK: [Google Scholar]

- Korf RP. 1973. Discomycetes and Tuberales . In: Ainsworth GC, Sparrow FK, Sussman AS. (eds), The Fungi: an advanced treatise Vol. IVA: 249 – 319 Academic Press, New York: [Google Scholar]

- Korf RP. 1983. Cyttaria (Cyttariales) – Coevolution with Nothofagus, and evolutionary relationship to the Boedijnopezizeae (Pezizales, Sarcoscyphaceae). Australian Journal of Botany Suppl. 10: 77 – 87 [Google Scholar]

- Kuntner M. 2006. Phylogenetic systematics of the Gondwanan nephilid spider lineage Clitaetrinae (Araneae, Nephilidae). Zoologica Scripta 35: 19 – 62 [Google Scholar]

- Kuntner M, Agnarsson I. 2006. Are the linnean and phylogenetic nomenclatural systems combinable? Recommendations for biological nomenclature. Systematic Biology 55: 774 – 784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landvik S. 1996. Neolecta, a fruit-body-producing genus of the basal ascomycetes, as shown by SSU and LSU rDNA sequences. Mycological Research 100: 199 – 202 [Google Scholar]

- Landvik S, Schumacher TK, Eriksson OE, Moss ST. 2003. Morphology and ultrastructure of Neolecta species. Mycological Research 107: 1021 – 1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Leigh JW, Brinkmann H, Cushion MT, Rodriguez-Ezpeleta N, Philippe H, Lang BF. 2009. Phylogenomic analyses support the monophyly of Taphrinomycotina, including Schizosaccharomyces fission yeasts. Molecular Biology and Evolution 26: 27 – 34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumbsch HT, Schmitt I, Lindemuth R, Miller A, Mangold A, et al. 2005. Performance of four ribosomal DNA regions to infer higher-level phylogenetic relationships of inoperculate euascomycetes (Leotiomyceta). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 34: 512 – 524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutzoni F, Kauff F, Cox CJ, McLaughlin D, Celio G, et al. 2004. Assembling the fungal tree of life: progress, classification, and evolution of subcellular traits. American Journal of Botany 91: 1446 – 1480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeill JF, Barrie F, Burdet HM, Demoulin V, Hawksworth DL, et al. 2006. International Code of Botanical Nomenclature (Vienna Code). Regnum Vegetabile Koeltz Scientific Books, Königstein: [Google Scholar]

- Miadlikowska J, Kauff F, Hofstetter V, Fraker E, Grube M, et al. 2006. New insights into classification and evolution of the Lecanoromycetes (Pezizomycotina, Ascomycota) from phylogenetic analyses of three ribosomal RNA- and two protein-coding genes. Mycologia 98: 1088 – 1103 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nannfeldt JA. 1942. The Geoglossaceae of Sweden (with regard also to the surrounding countries) Almqvist & Wiksell, Stockholm: [Google Scholar]

- Persoon CH. 1794. Neuer Versuch einer systematischen Eintheilung der Schwamme. Neues Magazin für die Botanik, Römer 1: 63 – 80 [Google Scholar]

- Pfeil BE, Crisp MD. 2005. What to do with Hibiscus? A proposed nomenclatural resolution for a large and well known genus of Malvaceae and comments on paraphyly. Australian Systematic Botany 18: 49 – 60 [Google Scholar]

- Platt JL. 2000. Lichens, earth tongues, and endophytes: evolutionary patterns inferred from phylogenetic analyses of multiple loci. PhD dissertation. Botany and Plant Pathology, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Porter TM, Schadt CW, Rizvi L, Martin AP, Schmidt SK, Scott-Denton L, Vilgalys R, Moncalvo JM. 2008. Widespread occurrence and phylogenetic placement of a soil clone group adds a prominent new branch to the fungal tree of life. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 46: 635 – 644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redhead SA. 1979. Mycological observations: 1, on Cristulariella, 2, on Valdensinia; 3, on Neolecta. Mycologia 61: 1248 – 1253 [Google Scholar]

- Reeb V, Lutzoni F, Roux C. 2004. Contribution of RPB2 to multilocus phylogenetic studies of the euascomycetes (Pezizomycotina, Fungi) with special emphasis on the lichen-forming Acarosporaceae and evolution of polyspory. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 32: 1036 – 1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandnes ACS. 2006. Phylogenetic relationships among species and genera of Geoglossaceae (Helotiales) based on ITS and LSU nrDNA sequences. Cand.scient. dissertation. The University of Oslo, Oslo. [Google Scholar]

- Schoch CL, Shoemaker RA, Seifert KA, Hambleton S, Spatafora JW, Crous PW. 2006. A multigene phylogeny of the Dothideomycetes using four nuclear loci. Mycologia 98: 1041 – 1052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoch CL, Sung G-H, López-Giráldez F, Townsend JP, Miadlikowska J, et al. 2009. The Ascomycota Tree of Life: A phylum wide phylogeny clarifies the origin and evolution of fundamental reproductive and ecological traits. Systematic Biology doi 10.1093/sysbio/syp020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher T, Sivertsen S. 1987. Sarcoleotia globosa (Sommerf. : Fr.) Korf, taxonomy, ecology and distribution . In: Larsen GA, et al. . (eds), Arctic Alpine Mycology Plenum Press, New York & London: 163 – 176 [Google Scholar]

- Seaver FJ. 1951. The North American cup-fungi (in-operculate) Seaver (published by the author), New York: [Google Scholar]

- Sennblad B, Bremer B. 2002. Classification of Apocynaceae s.l. according to a new approach combining Linnaean and phylogenetic taxonomy. Systematic Biology 51: 389 – 409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spatafora JW, Johnson D, Sung G-H, Hosaka K, O’Rourke B, et al. 2006. A five-gene phylogenetic analysis of the Pezizomycotina. Mycologia 98: 1018 – 1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spooner BM. 1987. Helotiales of Australasia: Geoglossaceae, Orbiliaceae, Sclerotiniaceae, Hyaloscyphaceae. Bibliotheca Mycologica 116: 1 – 711 [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. 2006. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22: 2688 – 2690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenroos S, Hyvönen J, Myllys L, Thell A, Ahti T. 2002. Phylogeny of the genus Cladonia s.lat. (Cladoniaceae, Ascomycetes) inferred from molecular, morphological, and chemical data. Cladistics 18: 237 – 278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama J, Hosaka K, Suh S-O. 2006. Early diverging Ascomycota: phylogenetic divergence and related evolutionary enigmas. Mycologia 98: 996 – 1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavares II. 1979. The Laboulbeniales. Mycological Memoirs 9: 1 – 627 [Google Scholar]

- Thaxter R. 1896. Contribution towards a monograph of the Laboulbeniaceae. Memoirs of the American Academy of Arts and Science 12: 187 – 429 [Google Scholar]

- Verkley GJM. 1994. Ultrastructure of the apical apparatus in Leotia lubrica and some Geoglossaceae (Leotiales, Ascomycotina). Persoonia 15: 405 – 430 [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Binder M, Schoch CL, Johnston PR, Spatafora JW, Hibbett D. 2006a. Evolution of helotialean fungi (Leotiomycetes, Pezizomycotina): A nuclear rDNA phylogeny. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 41: 295 – 312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Johnston PR, Takamatsu S, Spatafora JW, Hibbett DS. 2006b. Towards a phylogenetic classification of the Leotiomycetes based on rDNA data. Mycologia 98: 1065 – 1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Johnston PR, ang ZL, Townsend JP. 2009. Evolution of reproductive morphology in leaf endophytes. PLoS ONE 4: e4246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir A, Blackwell M. 2001. Molecular data support the Laboulbeniales as a separate class of Ascomycota, Laboulbeniomycetes. Mycological Research 105: 1182 – 1190 [Google Scholar]

- Weir A, Blackwell M. 2005. Phylogeny of arthropod ectoparasitic ascomycetes . In: Vega FE, Blackwell M. (eds), Insect-fungal associations: Ecology and evolution: 119 – 145 Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK: [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Castlebury LA, Miller AN, Huhndorf S, Schoch CL, et al. 2006. An overview of the systematics of the Sordariomycetes based on a four-gene phylogeny. Mycologia 98: 1076 – 1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang W-Y. 1998. Fungal Flora of China Vol. 8. Sclerotiniaceae and Geoglossaceae Science Press, Beijing, China: [Google Scholar]