Abstract

Background

Several studies suggest that standard verbal and written consent information for treatment is often poorly understood by patients and their families. This study examined the effect of an interactive computer-based information program on patients’ understanding of cardiac catheterization.

Methods

135 adult patients scheduled to undergo diagnostic cardiac catheterization were randomized to receive details about the procedure using either standard institutional verbal and written information (SI), or interactive computerized information (ICI) preloaded on a laptop computer. Understanding was measured using semi-structured interviews at baseline (i.e, before information was given), immediately following cardiac catheterization (Early understanding), and two weeks post-procedure (Late understanding). The primary study outcome was the change from baseline to Early understanding between groups.

Results

Subjects randomized to the ICI intervention had significantly greater improvement in understanding compared to those who received the SI (net change 0.81; 95% confidence interval: 0.01, 1.6). Significantly more subjects in the ICI group had complete understanding of the risks of cardiac catheterization (53.6% vs 23.1%, P< 0.05) and options for treatment (63.2% vs 46.2%, P< 0.05) compared to the SI group, respectively. Several predictors of improved understanding were identified including baseline knowledge (P< 0.001), younger age (P = 0.002), and use of the ICI (p = 0.003).

Conclusions

Results suggest that an interactive computer-based information program for cardiac catheterization may be more effective in improving patient understanding than conventional written consent information. This technology, therefore, holds promise as a means of presenting understandable detailed information regarding a variety of medical treatments and procedures.

INTRODUCTION

Beauchamp and Childress describe three required elements of informed consent i.e., the threshold, information, and consent elements.1 Unfortunately, several studies suggest that the essence of the information element i.e., disclosure, recommendation of a plan, and understanding is often not achieved due to poor disclosure and a lack of understanding of the material.2–5 This is important given that a lack of understanding may cause patients to misinterpret the risks and benefits of a treatment or procedure and impair their ability to follow a prescribed treatment regimen.

Given that the standard verbal and/or written methods of communicating medical information are often inadequate, several alternative strategies have been explored with mixed success.6 Such strategies include the use of modified consent forms with improved readability and processability (formatting),7, 8 inclusion of graphics,9, 10 extended discussions,11 teaching aids,12 and video technology. Of these, video presentations have shown promise in improving patients’ knowledge of treatments and procedures including colonoscopy,13 knee arthroscopy,14 hormone replacement therapy,15 and the use of intravenous contrast media.16 However, video presentations have limitations in that they do not promote active participation in learning and decision-making and, like written information, tend to be targeted to groups of patients rather than tailored to the learning ability and information needs of the individual patient.

Interactive computer-based technologies offer the potential to overcome some of these limitations by promoting active participation in learning and allowing subjects to access information that is consistent with their learning styles and health literacy. However, the effectiveness of this approach in meeting the requirements for informed consent and patient understanding is relatively unknown.17, 18 This study, therefore, was designed to test the hypothesis that use of an interactive computer-based information program for cardiac catheterization would result in improved patient understanding compared to standard verbal and written information. The primary outcome measure was the change in understanding from baseline (i.e., before information was given) to just after completion of cardiac catheterization (Early understanding).

METHODS

1) Population

This study was approved by the University of Michigan’s Institutional Review Board with a waiver of written informed consent since the study constituted no more than minimal risk and did not deny subjects information that they would normally receive. Consecutive adult (> 18yrs) patients were approached as they arrived approximately 1 hour prior to scheduled elective diagnostic cardiac catheterization. Patients who had undergone a previous catheterization within 3 years and those undergoing emergency catheterization were excluded. Eligible patients were randomized (tables of random numbers) to receive information about cardiac catheterization in one of two ways i.e., verbal and written information per the institution’s standard consent protocol (SI), or interactive computerized information (ICI) preloaded on a laptop computer. All subjects were told that they would be approached separately by a member of the cardiology team (not part of the study) in order to obtain their signature for consent for cardiac catheterization.

2) Baseline Assessment

Subjects were transferred to a private holding area where they were given a short semi-structured, open-ended, pre-intervention interview to elicit their baseline understanding of six core elements of the cardiac catheterization procedure, i.e, medical indication, purpose, protocol, risks, benefits, and alternative treatments (Baseline test, see appendix). The responses to each of the core element questions were written down verbatim by trained research assistants who were allowed to clarify questions and prompt the subjects for additional information but were unable to offer any specific details of the procedure. The interview process and measurement of understanding have been presented previously.8, 19 Subjects were also asked what information they had reviewed prior to this procedure. In our setting, patient education regarding cardiac catheterization is available as a brochure mailed by the Department of Cardiology, information on the hospital website, and verbal information provided by the patient’s primary care provider or person scheduling the catheterization procedure.

3) Intervention

Following the baseline assessment, subjects were given information about cardiac catheterization using either the SI or ICI.

a) Standard Information Protocol (SI)

In our setting, consent for cardiac catheterization is routinely obtained on the day of the procedure by a cardiology fellow or a physician’s assistant who provide verbal information regarding the procedure, the risks and benefits, and the options for treatment. The document used is an institutional generic consent for surgical and other procedures, customized to include the risks and benefits of the specific procedure to be performed.

b) Interactive Computerized Information (ICI)

The ICI for cardiac catheterization (ArchieMD, Inc. Boca Raton, FL) was developed using advanced 2 and 3-D graphic technology to create a “virtual” patient, animated to simulate a variety of dynamic physiological functions e.g., beating heart. The program content was based on a review of existing consent documents, review of the extant literature, and expert opinion (cardiologists and computer graphic designers). Prior to beginning the study, the program underwent final review by a panel of expert and lay individuals (i.e., cardiologists, informed consent experts, nurses, students, and patients) for content, visual interface, and navigation. Sequential information on cardiac catheterization was provided through dynamic 2- and 3-D graphics, text, and narrative. Additional information could be accessed as needed by clicking on specified underlined items. At any time while navigating the program, subjects were able to type in questions that they had about the procedure. These questions could then be accessed at the end of the program and relayed to the cardiologist.

The program included the following modules:

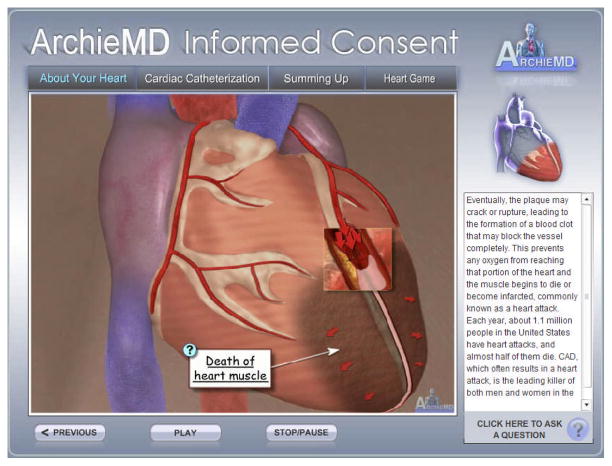

i) “About Your Heart”

This module included subsections on the “Healthy heart” “Heart disease,” and “Treatment options.” Each screen was presented in sequence and could not be “skipped.” Information was presented using 3-D animation of the beating heart with “zoom-in” features to detail items such as coronary artery blockage and ischemia (Fig. 1). Information was further enhanced by a “voice over” narrative and by “scrollable” text on the screen.

Figure 1.

A screenshot from the interactive computer program highlighting the consequences of coronary artery blockage. When live, the heart actively “beats.”

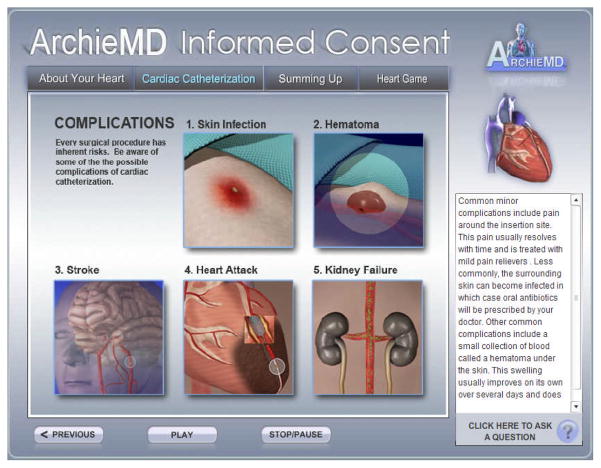

ii) “Cardiac Catheterization”

This module described the cardiac catheterization procedure including catheter placement and introduction of the contrast dye. The patient was also shown how a blockage appears on an actual angiogram. The module also described angioplasty and stent placement and other treatment options as potential consequences of an identified blockage in the coronary artery(ies). Subsequent screens described the “Risks” and “Benefits” of cardiac catheterization (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

A screenshot from the interactive computer program highlighting the risks of cardiac catheterization.

iii) “Summary and Optional Quiz”

A summary of all the information was provided in this final module together with a short optional quiz to ascertain the subjects’ understanding of the key elements of the procedure. The quiz consisted of 11 items; 7 required subjects to identify certain items on the simulated graphics e.g., plaque build-up, and 4 were multiple-choice questions.

One computer preloaded with the ICI was used. An ancillary speaker was added to ensure that subjects who were hard of hearing were able to listen to the narrative. A research assistant was present during the subject’s navigation through the program to ensure completion and to offer assistance as needed. Completion of the core modules and summary took approximately 10–12 minutes after which time the cardiology care-giver obtained the subject’s signature to undergo cardiac catheterization using the institutional consent document for procedures.

4) Post-procedure Interviews

Once the subject had fully recovered from the cardiac catheterization procedure and prior to discharge, he/she was interviewed again using the same semi-structured interview to determine their “new” understanding of the information (Early understanding). Subjects were also given a short questionnaire to obtain a subjective self-assessment of the clarity and amount of information, their perceived effectiveness of the message delivery, and their overall satisfaction with the information received using 0–10 numbers scales (where 10 = high). Additionally, demographic information was obtained including age, gender, education, socioeconomic status, and race/ethnicity. Subjects also completed the shortened versions of the Rapid Estimate of Adult Learning in Medicine (REALM) reading test20 and Need for Cognition test.21 Need for cognition (NFC) refers to an individual’s tendency to engage in and enjoy effortful cognitive endeavors. Subjects were categorized as having low or high NFC based on the median split. A third interview was administered via telephone 2 weeks following the procedure to measure long-term knowledge retention (Late understanding).

5) Scoring Understanding

The transcribed responses to questions regarding the risks and benefits, etc., of cardiac catheterization were scored independently by two assessors who were blinded to the subjects’ group assignment. Guidelines for scoring were determined a priori. Scores of 0 (no understanding), 1 (partial understanding) and 2 (complete understanding) were assigned for each core element, and scores were combined to provide an overall score of understanding (range 0–12, where 12 = complete understanding). The scoring system used was based on the Deaconess Informed Consent Comprehension Test22 and has been described previously.8, 19

6) Statistical Analysis

Sample size determination was based on a previous study which showed that understanding of a standard consent form was 6.4 ± 1.4 (scale of 0–10) and that understanding of a modified form with improved processability (format and graphics) was 7.2 ± 1.5.8 Accepting this difference as the smallest that we believed to be clinically important to detect, we required a sample of 66/group (α = 0.05, β = 0.1, two-sided). Data were analyzed using unpaired t tests, Mann Whitney-U, chi-square, and Fisher’s Exact tests, as appropriate. Subject-specific changes between baseline and Early/Late understanding were compared between groups. Inter-rater agreement between the two assessors were performed using the kappa (κ) statistic. Kappa values of ≥ 0.7 were considered to represent acceptable levels of agreement. Independent factors found to be associated with Early understanding by univariate analysis (P< 0.1) were subsequently entered into a multivariate regression with stepwise selection. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS® statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

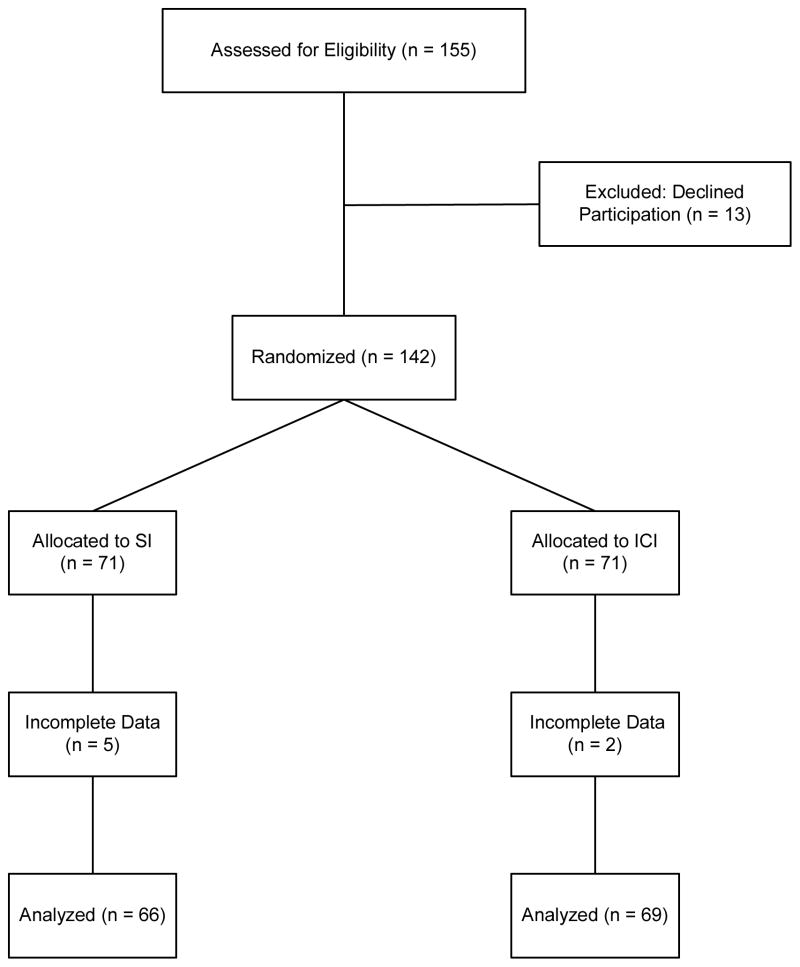

A total of 155 adult patients were approached to participate in this study over a 7 month period (6/08–12/08). Of these, 13 declined to participate and 7 were excluded due to incomplete information or withdrawal from the study. Data are thus presented for 135 subjects (Fig. 3). Subjects who declined to participate in the study were similar demographically to participants but tended to be more anxious. Reasons for non-participation were: “too nervous” (53.8%), “didn’t want to watch a video” (46.2%), “didn’t want to be told about the procedure” (23.1%), and “didn’t want to be bothered with anything extra before the procedure” (38.5%). Of the seven patients who did not complete the interviews or were withdrawn from the study, 4 had been randomized to the SI and 3 to the ICI. Reasons for withdrawal included postponement of the procedure due to medical reasons (2), loss to follow-up (3), patient couldn’t hear the computer narrative (1), and “too many questions” (1).

Figure 3.

Flow diagram of participant progress through the phases of the study

The demographics of the study sample are described in table 1. There were no differences in demographics between the two experimental groups although the ICI group had significantly (P< 0.05) more outpatients compared to the SI group. This however, had no effect on understanding. A similar number of subjects in each group spoke English as their primary language. There were no differences between groups with respect to information sought or accessed prior to their cardiac catheterization. Only one subject reported receiving no information prior to their procedure. The majority (73.1%) obtained information from a doctor or nurse, 23.1% from a family member or friend, 13.4% from the internet, 50.7% from a book or magazine, and 3.0% from television or radio. Many subjects obtained information from more than one of these sources. Subjects who received the ICI reported having “average” comfort with using computers (5.8 ± 3.6 out of 10, where 10 = extremely comfortable). Although the majority of subjects (74.2%) did not require help with the computer program, 18.2% required “some help” and 7.6% needed a “lot of help.” There were, however, no differences in understanding between those who needed help (8.6 ± 2.2) and those who did not (9.3 ± 2.2). Inter-rater reliability between the assessors’ scores of subject understanding showed excellent agreement. Kappa statistics for each of the core elements (i.e., risks, benefits, etc.) ranged from 0.71–1.0 (P< 0.001).

Table 1.

Demographics by Message Delivery

| Standard (SI, n = 66) | Interactive (ICI, n = 69) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs, mean ± SD) | 59.4 ± 12.8 | 61.6 ± 13.3 |

| Gender (F/M) % | 48.4/51.6 | 50/50 |

| Race/ethnicity (%): | ||

| Caucasian | 52 (83.9) | 62 (91.2) |

| African American | 8 (12.9) | 3 (4.4) |

| Hispanic | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 1 (1.6) | 3 (4.4) |

| Level of Education (%): | ||

| ≤High school graduate | 16 (26.7) | 20 (30.8) |

| Some college/trade school | 18 (30.0) | 13 (20.0) |

| ≥ Bachelor’s degree | 26 (43.3) | 32 (49.2) |

| Catheterization procedure (%): | ||

| Right Heart | 1 (1.5) | 4 (5.8) |

| Left Heart | 43 (65.2) | 44 (63.8) |

| Right and Left Heart | 22 (33.3) | 21 (30.4 |

| Admission type (%): | ||

| Outpatient | 48 (72.7) | 62 (89.9)* |

| Inpatient | 18 (27.3) | 7 (10.1)* |

| English as primary language | 59 (95.2) | 61 (89.7) |

| Pre-procedure anxiety | 5.6 ± 2.9 | 5.9 ± 3.1 |

| REALM (literacy, mean ± SD) | 64.1 ± 2.7 | 63.3 ± 7.4 |

| NFC (mean ± SD) | 22.5 ± 3.0 | 22.2 ± 2.7 |

P = 0.01 vs Standard,

REALM = Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (0–66 scale, where 66 = High literacy). NFC = Need for Cognition (0–35 scale, where 35 = High NFC)

The study’s primary outcome, the net change in Early understanding from baseline between the SI and ICI groups was 0.81; 95% confidence interval: 0.01, 1.6 (Table 2). There were no differences in baseline understanding of cardiac catheterization between the two groups, however, subjects who received information using the ICI had a significantly greater improvement in early understanding as compared to patients receiving the SI (P< 0.05). There was a trend towards greater early understanding of all the individual information elements (e.g., risks, options, etc.) among patients who received the ICI, however significance was achieved only for understanding of the risks and options for treatment (table 2). Late understanding (i.e., 2 weeks post-procedure) decreased slightly in both groups but was not significantly different between them. The effect of age, education, literacy, and NFC on early understanding by groups is shown in table 3. Overall, subjects who were younger and had higher literacy had significantly greater understanding of the material. Table 4 describes the subjects’ perceptions of, and satisfaction with the quality and effectiveness of the information between groups. As shown, there were no differences observed.

Table 2.

Comparison of Changes from Baseline to Early and Late Understanding between the ICI and SI groups.

| Tests | Standard (SI) | Interactive (ICI) | Mean difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline understanding (before ICI or SI) | 6.8 ± 2.4 | 6.9 ± 2.9 | 0.16 (−0.07, 1.1) |

| Early understanding (after ICI or SI) | 8.1 ± 2.3 | 9.3 ± 2.2* | 1.2 (0.4, 1.9) |

| “Complete” early understanding of the: | |||

| Medical indication for catheterization | 67.7% | 76.8% | |

| Purpose of catheterization | 70.8% | 83.8% | |

| Catheterization protocol | 41.5% | 53.6% | |

| Risks | 23.1% | 53.6%* | |

| Benefits | 47.7% | 49.3% | |

| Options for treatment | 46.2% | 63.2%* | |

| Late understanding (2 wks after ICI or SI) | 7.9 ± 2.2 | 8.6 ± 2.7 | 0.65 (−0.4, 1.7) |

| Δ Baseline – Early understanding | 1.3 ± 2.5 | 2.2 ± 2.1* | 0.81 (0.01, 1.6) |

| Δ Baseline – Late understanding | 1.2 ± 1.9 | 1.4 ± 2.3 | 0.24 (−0.7, 1.1) |

| Δ Early – Late understanding | −0.2 ± 2.6 | − 0.6 ± 1.8 | −0.44 (−1.4, 0.5) |

Data are presented as % and mean ± SD (based on a scale of 0–12, where 12 = Complete understanding). CI = Confidence interval.

Δ = Change in understanding score.

P< 0.05 vs Standard.

Table 3.

Early Understanding by Message Delivery and Age, Education, Literacy, and NFC

| Standard (SI) | Interactive (ICI) | Mean Difference (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs): | |||

| 18–59 (R) | 8.3 ± 2.3 | 9.9 ± 1.7† | 1.7 (0.7, 2.7) |

| ≥60 | 7.9 ± 2.3 | 8.7 ± 2.4* | 0.8 (−0.4, 1.9) |

| Education: | |||

| < Bachelor’s Degree (R) | 7.9 ± 2.2 | 8.9 ± 2.3 | 1.0 (−0.07, 2.1) |

| ≥ Bachelor’s Degree | 8.5 ± 2.0 | 9.6 ± 2.1† | 1.1 (0.01, 2.2) |

| Literacy: | |||

| Low (R)a | 6.3 ± 2.9 | 7.7 ± 1.6 | 1.4 (−1.8, 4.7) |

| Highb | 8.1 ± 2.3 | 9.8 ± 2.0†* | 0.9 (0.02, 1.9) |

| NFC | |||

| Low (R)c | 8.8 ± 2.1 | 9.4 ± 2.3 | 0.56 (−0.8, 1.9) |

| Highd | 7.6 ± 2.1* | 9.3 ± 2.1† | 1.7 (0.7, 2.7) |

Data are presented as mean ± SD

(R) = Reference Group.

P < 0.05 vs Reference group.

P < 0.05 vs Standard

Low literacy = 0–60 (3rd – 8th grade equivalence),

High literacy = 61–66 (≥9th grade) on Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine scale (REALM), CI = Confidence interval NFC = Need for Cognition.

Low NFC = 0–21,

High NFC = ≥ 22 Cut-off based on median split.

Table 4.

Perceptions of the Message Delivery

| Standard (SI) | Interactive (ICI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Quality of Information | 9.2 ± 1.5 | 9.4 ± 1.2 |

| Ability to follow information | 9.5 ± 0.9 | 9.4 ± 1.3 |

| Effectiveness of presentation | 9.5 ± 1.1 | 9.5 ±1.0 |

| Overall satisfaction | 9.5 ± 1.0 | 9.5 ± 1.3 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD based on 0–10 scales where 10 = High

Of those who received the ICI, 17 (29.8%) attempted the quiz at the end, 23 (40.4%) “did not want to,” and 17 (29.8%) “would have liked to but did not have time.” Eighty-eight percent of patients who attempted the quiz found it to be helpful, however, there was no difference in understanding of the information between those who took the quiz compared to those who did not. Only 3 patients typed in questions on the computer. The low utilization of this function may reflect the patients’ perceived high level of understanding, or may have represented a perceived lack of time or added burden.

Factors that were found to be associated with early understanding by univariate analysis (P< 0.1) were entered into a multivariate regression model with stepwise selection. These factors included the intervention group, and the subjects’ baseline understanding, age, literacy, NFC, education, perception of the quality of the information, and satisfaction. Factors determined to be predictive of improved understanding are described in Table 5.

Table 5.

Multiple Regression of Factors Predictive of Improved Change in Early Understanding

| Beta Coefficient | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline Understanding | 0.634 | 0.000 |

| Younger Age (18–60 yrs) | 0.246 | 0.002 |

| ICI Group | 0.239 | 0.003 |

ICI = Interactive computerized information

DISCUSSION

Results of this study showed that subjects who received information about cardiac catheterization using the ICI demonstrated significantly greater improvement in overall Early understanding from baseline compared to those receiving standard information. Although the difference in overall Early understanding was relatively modest, the effect of the ICI on understanding of the core information elements was clinically significant. For example, of those who received the ICI, almost twice as many had complete understanding of the risks and a third more had complete understanding of the options for treatment compared to those receiving the SI. This is particularly important as studies have shown that the understanding of risk is one of the most important determinants of informed decision-making.23, 24 These findings reinforce the need for improved diligence and strategies to ensure that patients understand these critical elements.

Traditionally, information for medical treatments or procedures is presented in written and/or verbal formats. However, studies suggest that this standard approach often results in poor patient understanding of the material.2, 4, 5, 8, 25, 26 In one study, only 18% of cataract patients could recall the risks immediately after being given consent2 and, in another, 88% of patients could not recall specific information regarding the risks of blood transfusions.26 The reasons for this include: material written above the recommended 8th grade reading level, incomplete and/or expedited disclosure, use of unfamiliar medical terminology, and variability in the clarity and amount of information.

The results showed that information provided by the ICI on the day of cardiac catheterization resulted in improved understanding compared to the standard consent. There was some initial concern regarding the presentation of detailed information of risks and benefits just before surgery, however, we were encouraged to find that the vast majority of patients responded positively to the ICI. Although beyond the scope of this study, it may be that presenting this information prior to the day of catheterization may result in even better understanding. However, we should note that in a previous study, understanding of consent information was found to be similar regardless of whether it was presented on the day of surgery or several days prior.27

Computer-based technologies for communicating health information offer several potential advantages over standard methods by providing a media rich interface that encourages participation in learning.17 Systematic reviews of the literature reveal that computerized educational interventions for chronic conditions such as diabetes, asthma, and arthritis are positively received by patients, and elicit a greater sense of control and understanding of their conditions.18, 28 Despite the apparent usefulness of these technologies there is however, a paucity of data related to their use as a means to provide consent information. In a study by Shaw et al. a multimedia computer-assisted instruction for colonoscopy was shown to improve overall patient understanding compared to standard education although comprehension of certain items was not affected by the message format.17 Furthermore, in a survey of patients’ perceptions of a preoperative computer-based program for cholecystectomy, over two-thirds of the respondents ranked the clarity of both the text and the illustrations as excellent.29

The computer program used in this study was unique in that it was interactive and utilized 2- and 3-D animation to produce a “virtual” patient. To our knowledge, there are very limited data on the effect of this type of technology on patient understanding of medical information. In a German study, 3-D technology describing surgical thyroidectomy resulted in improved overall understanding and lowered anxiety compared to standard text.30

A potential advantage of interactive computerized systems is the ability to “tailor” the information to the learning style and information preferences of the individual. Indeed, the concept of tailoring has been shown to be extremely effective in helping individuals change health-related behaviors such as smoking, diet, and physical activity.31–33 The program used in this study allowed for some degree of tailoring in that patients were able to access additional information per their individual needs. However, given that the ICI was shown to improve understanding to a greater extent among those who were younger and had higher literacy, further tailoring of the information using this type of technology may be necessary to ensure that those who are older or have different information needs are equally informed.

Although short-term understanding of the information was improved among patients receiving the ICI, longer-term (2-week) retention was independent of the method of information delivery. However, in both groups, retention of information decreased slightly over the two weeks following presentation of the information. This is consistent with previous studies showing a decline in retention of medical information over time.34 There was a slightly larger lack of retention of information in the ICI group compared to the SI group although this was not significantly different. The reason for this is unclear, particularly in light of the fact that we were unable to determine if additional information had been obtained in the post-operative period that may have disproportionately affected one group over the other.

There were no differences in the subjects’ satisfaction or perceptions of the quality of the information between the two groups. This suggests that patients are usually satisfied with the information they are given even though they may not completely understand it. Unfortunately, due to time constraints, we were unable to have the subjects directly compare the two methods of message delivery which may have resulted in differences in perception and satisfaction.

A few points regarding the limitations of the study design are warranted. First, this study involved elements of survey research and, as such, was subject to the potential biases of non-response and self-reports. However, given that very few subjects declined participation, the potential for non-response bias was likely minimal. Likewise, since the questionnaires contained no identifying information, the chance for self-report bias was also low. Second, this study represents one intervention among one population at one institution and thus may not be generalizable to other situations or populations. Third, we recognize that since the sample size was based on expected differences in early understanding between groups, the sample may not have been sufficiently powered to detect differences in all univariate and multivariate comparisons. Finally, despite the fact that the ICI resulted in improved understanding of the information, it remains unknown whether or how its use affected the decision to undergo cardiac catheterization. Previously, we showed that subjects with greater understanding were more likely to participate in a research study,19 however, although the ICI improved understanding, its effect on decision-making is not known. No patient in the study refused cardiac catheterization although it is likely that the decision to undergo the procedure was made prior to arrival. Unfortunately, data regarding any patient refusal to undergo catheterization were not available. Further studies to examine the effect of this technology on decision-making may be warranted.

In summary, results of this study showed that an interactive computer program for cardiac catheterization was more effective in improving patient understanding than conventional written and verbal information. This suggests that computer-based technologies hold promise as a means of presenting understandable detailed information regarding a variety of medical treatments and procedures.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Lindsey Kelly, B.S., (Research Assistant), Jennifer Hemburg, (Undergraduate) Caela Hesano, (Undergraduate), Elsa Pechlivanidis, (Undergraduate) and Lauren Perlin (Undergraduate) from the Department of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan for subject recruitment and data collection.. Those acknowledged received no compensation for their participation and have no financial, commercial or other interests in ArchieMD, Inc.

Financial support: Supported in part by a grant to Dr. Levine from the National Institutes of Health; NHLBI (R41 HL087488). Dr. Tait is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health; NICHD (R01 HD053594).

Footnotes

Not registered in a clinical trial registry

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Levine is the President and Chief Medical Officer of ArchieMD, Inc. but was funded independently for this project by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Levine was responsible for the development of the interactive prototype but had no involvement in subject recruitment, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data. None of the other investigators have any financial, commercial, or other interests in ArchieMD, Inc.

References

- 1.Beauchamp T, Childress J. Principles of biomedical ethics. New York: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vallance J, Ahmed M, Dhillon B. Cataract surgery and consent; recall, anxiety, and attitude toward trainee surgeons preoperatively and postoperatively. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30:1479–1485. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2003.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byrne D, Napier A, Cuschieri A. How informed is signed consent? BMJ. 1988;296:839–840. doi: 10.1136/bmj.296.6625.839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrett R. Quality of informed consent: measuring understanding among participants in oncology clinical trials. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32:751–755. doi: 10.1188/05.ONF.751-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stryker J, Wray R, Emmons K, Winer E, Demetri G. Understanding the decisions of cancer clinical trial participants to enter research studies: Factors associated with informed consent, patient satisfaction, and decisional regret. Patient Educ & Counsel. 2005;63:104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flory J, Emanuel E. Interventions to improve research participants’ understanding in informed consent for research. JAMA. 2004;202(13):1593–1601. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.13.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dresden G, Levitt M. Modifying a standard industry clinical trial consent form improves patient information retention as part of the informed consent process. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:246–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb01300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tait AR, Voepel-Lewis T, Malviya S, Philipson S. Improving the readability and processability of a pediatric informed consent document: effects on parents’ understanding. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:347–352. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.4.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lipkus I, Hollands J. The visual communication of risk. J Nat Cancer Inst Monographs. 1999;25:149–163. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schapira M, Nattinger A, McHorney C. Frequency or probability? A qualitative study of risk communication formats used in health care. Med Decis Making. 2001;21:459–467. doi: 10.1177/0272989X0102100604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aaronson N, Visser-Pol E, Leenhouts G, et al. Telephone-based nursing intervention improves the effectiveness of the informed consent process in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:984–996. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.3.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coletti A, Heagerty P, Sheon A, et al. Randomized, controlled evaluation of prototype informed consent process for HIV vaccine efficacy trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32:161–169. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200302010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agre P, Kurtz R, Krauss B. A randomized trial involving videotape to present consent information for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:271–276. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(94)70054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rossi M, Guttmann D, MacLennan M, Lubowitz J. Video informed consent improves knee arthroscopy patient comprehension. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:739–743. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rostom A, O’Connor A, Tugwell P, Wells G. A randomized trial of a computerized versus and audio-booklet decision aid for women considering post-menopausal hormone replacement therapy. Patient Educ and Counsel. 2002;46:67–74. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hopper K, Zajdel M, Hulse S, et al. Interactive method of informing patients of the risks of intravenous contrast media. Radiology. 1994;192:67–71. doi: 10.1148/radiology.192.1.8208968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaw M, Beebe T, Tomshine P, Adlis S, Cass O. A randomized, controlled trial of interactive, multimedia software for patient colonoscopy education. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;32:142–147. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200102000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krishna S, Balas E, Spencer D, Griffin J, Boren S. Clinical trials of interactive computerized patient education: implications for family practice. J Fam Pract. 1997;45:25–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tait AR, Voepel-Lewis T, Malviya S. Do they understand? (Part I): Parental consent for children participating in clinical anesthesia and surgery research. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:603–608. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200303000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis T, Long S, Jackson R, et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: A shortened screening instrument. Fam Med. 1993;25(6):391–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cacioppo J, Petty R, Kao C. The efficient assessment of need for cognition. J Personality Assess. 1984;48:306–307. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4803_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller C, O’Donnell D, Searight H, Barbarash R. The Deaconess Informed Consent Comprehension Test: an assessment tool for clinical research subjects. Pharmacotherapy. 1996;16(5):872–878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tait AR, Voepel-Lewis T, Malviya S. Participation of children in clinical research: Factors that influence a parent’s decision to consent. Anesthesiology. 2003;99:819–825. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200310000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tait AR, Voepel-Lewis T, Munro H, Malviya S. Parents’ preferences for participation in decisions made regarding their child’s anesthetic care. Paediatr Anaesth. 2001;11:283–290. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2001.00651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cassileth BR, Zupkis RV, Sutton-Smith K, March V. Informed consent -- why are its goals imperfectly realized? N Engl J Med. 1980;302(16):896–900. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198004173021605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan T, Eckert K, Venesoen P, Leslie K, Chin-Yee I. Consenting to blood: what to patients remember? Transfusion Med. 2005;15:461–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2005.00622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tait AR, Voepel-Lewis T, Siewert M, Malviya S. Factors that influence parents’ decisions to consent to their child’s participation in clinical anesthesia research. Anesth Analg. 1998;86(1):50–53. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199801000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewis D. Computer-based approaches to patient education. JAMIA. 1999;6:272–282. doi: 10.1136/jamia.1999.0060272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kessler T, Nachbur B, Kessler W. Patients’ perceptions of preoperative information by interactive computer program-exemplified by cholecystectomy. Patient Educ & Counsel. 2005;59:135–140. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hermann M. 3-dimensional computer animation - a new medium for supporting patient education before surgery. Acceptance and assessment of patients based on prospective randomized study - picture versus text [German] Chirug. 2002;75:500–507. doi: 10.1007/s00104-001-0416-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skinner C, Strecher V, Hospers H. Physicians’ recommendations for mamography: Do tailored messages make a difference. Am J Pub Hlth. 1994;84:43–49. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strecher V, Bishop K, Bernhardt J, Thorp J, Cheuvront B, Potts P. Quit for keeps: Tailored smoking cessation guides for pregnancy and beyond. Tobacco Control. 2000;(Suppl 3):78–79. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.suppl_3.iii78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strecher V, Kreuter M, Den Boer D, Kobrin S, Hospers H, Skinner C. The effects of computer-tailored smoking cessation messages in family practice settings. J Fam Pract. 1994;39:262–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van der Meulen N, Jansen J, van Dulmen S, Bensing J, van Weert J. Interventions to improve recall of medical information in cancer patients: a systematic review of the literature. Psych-Oncol. 2008;17:857–868. doi: 10.1002/pon.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]