Abstract

As the tumor vasculature is a key element of the tumor stroma, angiogenesis is the target of many cancer therapies. Recent work published in BMC Cell Biology describes a fusion protein that combines a peptide previously shown to home in on the gastric cancer vasculature with the anti-tumor cytokine TNF-α, and assesses its potential for gastric cancer therapy.

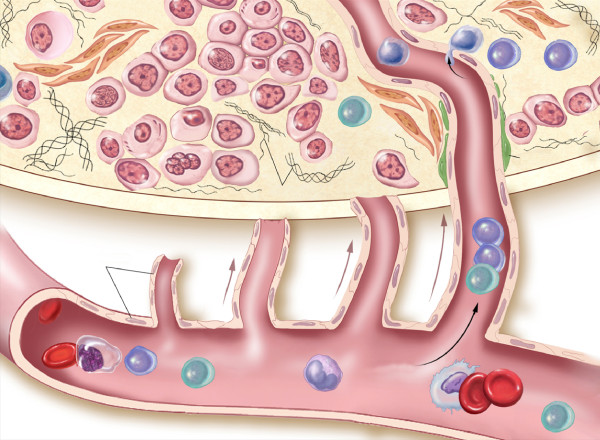

The microenvironment of any solid tumor is composed not only of the cancer cells themselves but also of the surrounding stromal tissue - composed of fibroblasts, endothelial cells and pericytes of capillary walls, smooth muscle, and immune and inflammatory cells (Figure 1). This elaborate infrastructure is instrumental in the growth, invasion and metastasis of a cancer. Stephen Paget, in 1889, was the first to suggest that the tumor micro-environment might influence tumor cell behavior, with his 'seed and soil' hypothesis. He reported that, like seeds, tumor cells randomly scattered throughout the vasculature could only metastasize if they landed in 'fertile soil' [1].

Figure 1.

Schematic of the tumor microenvironment, including tumor cells, endothelial cells, pericytes, fibroblasts, CD+ and CD- lymphocytes and extracellular matrix components.

More recently, normal stroma has been shown to inhibit tumor growth, whereas tumor stroma encourages it. In a study in which simian virus 40 (SV40)-transformed normal prostate epithelial cells were grafted into mice, it was found that cancer-associat ed fibroblasts (CAFs) supported the tumor cells. Normal prostate cells combined with CAFs began to take on the characteristics of carcinogenic prostate cells, whereas normal prostate cells combined with fibroblasts from normal tissue did not. Likewise, prostate cells immortalized by SV40 transformation grew massive tumors when combined with CAFs, whereas there was no tumor growth in the presence of normal fibroblasts [2].

Tumor angiogenesis

The stroma of a solid tumor is vital for its survival, and a key component in this respect are the blood vessels. When a tumor grows to greater than 2 to 4 mm3 in size, it requires new vessel growth for adequate oxygen and nutrient delivery, and for removal of waste products [3]. The growth of new capillaries into the tumor is called 'tumor angiogenesis', a term coined by Judah Folkman in 1971. Angiogenesis is induced by the release of various pro-angiogenic cytokines by the tumor cells and their supporting cells. Pro-angiogenic factors are involved in endothelial cell proliferation and migration, the formation of endothelial cells into new vasculature, and the degradation of the basement membrane and the extracellular matrix by proteolysis. Many different and functionally redundant factors are involved in angiogenesis [4], and a list of some of the most important is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Angiogenesis factors

| Factors affecting endothelial proliferation and migration | |

| VEGF family (vascular endothelial growth factors) | Mediate vascular permeability, endothelial proliferation, migration, and survival |

| FGF family (fibroblast growth factors) | Have roles in neuronal signaling, inflammatory processes, hematopoiesis, angiogenesis, tumor growth, and invasion |

| PDGF (platelet-derived growth factor) | Induces angiogenesis, cellular proliferation and migration in synergy with transforming growth factor beta (TGFB) and EGF |

| EGF (epidermal growth factor) | Involved in tumor proliferation, metastasis, apoptosis, angiogenesis, and wound healing |

| Angiopoietins (Ang1, Ang2) | Endothelial cell adhesion, spreading, focal contact formation, and migration |

| Angiopoietin-related growth factors | For example, ANGPTL3, FARP, PGAR |

| TIE receptors (TIE1, TIE2) | Essential in embryonic angiogenesis; endothelial motility |

| Eph receptors and Ephrins | Promote migration, repulsion, adhesion and attachment to the extracellular matrix via integrins |

| HGF (hepatocyte growth factor) | Neuronal survival factor; proliferation, migration and differentiation of various cell types |

| TP (thymidine phosphorylase) | Induces endothelial chemotaxis |

| NPY (neuropeptide Y) | Endothelial cell adhesion, migration and differentiation into capillaries |

| Factors affecting the basement membrane and extracellular matrix | |

| TF (tissue factor) | Upregulates VEGF on endothelial cells; starts coagulation process, leading to creation of two pro-thrombin fragments |

| Thrombin | Endothelial and tumor cell mitogen, increases metastasis in vivo |

| uPA (plasminogen activator, urokinase) | Only expressed in angiogenic endothelium; has a role in preventing excessive extracellular membrane proteolysis |

| tPA (tissue plasminogen activator) | Role in angiogenesis, as it is inhibited by angiogenesis inhibitor angiostatin |

| Plasmin | Scavenges α2-antiplasmin and α2-macroglobulin |

| Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) | Release extracellular membrane-bound growth factors |

| Chymases | Role in proteolysis |

| Heparanases | Role in proteolysis |

| Integrins | Role in attachment of endothelial cells to basement membrane, extracellular membrane, and other endothelial cells |

Multiple different and redundant factors are involved in the complex process of angiogenesis. This table represents a sample of those factors with roles in endothelial proliferation and migration, and in the degradation of the basement membrane and extracellular matrix. Adapted from [4].

One pro-angiogenic factor highly expressed in most tumors is vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and many VEGF and VEGF-receptor antagonists have been developed in the search for therapeutic agents that could prevent tumor angiogenesis. Most notably, bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody against VEGF, was the first angiogenesis inhibitor proven to delay tumor growth and significantly extend patients' lives. It was approved by the US Federal Drug Administration (FDA) in 2004 for first-line use in the treatment of colorectal cancer and has since been approved for a variety of other cancers, including non-small cell lung cancer, metastatic HER2-negative breast cancer, glioblastoma and metastatic renal cell carcinoma [5].

The cytokine tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) is also highly expressed in tumors and is thought to be pro-angiogenic. Paradoxically, it is also a potent anti-vascular cytokine at higher doses (it was named for its anti-tumor activity) and can be used clinically to destroy tumor vasculature. TNF-alpha is able to initiate cellular apoptosis and it is possible that these apoptotic pathways are deactivated in tumor cells [6]. Unfortunately, TNF-α has powerful and toxic systemic side effects and has only limited uses at present. Much work is under way to devise ways of targeting TNF-α specifically to tumors. In a recent paper in BMC Cell Biology, Daiming Fan and colleagues (Chen et al. [7]) investigate one approach to targeting of TNF-α, in this case to gastric tumors. They have fused it with a peptide known to target the human gastric cancer vasculature and injected the construct into the circulation of mice containing tumors of human gastric cancer cells.

The clinical potential of TNF-α

So far, TNF-α has fallen short of expectations in clinical use as an anti-tumor agent as a result of its high systemic toxicity at therapeutic doses. This has led to its development as a localized therapy, as in isolated organ perfusion for human melanoma and soft tissue sarcoma [8]. Although results are promising, with notable diminution in systemic side effects, localized tumor perfusion is not a reasonable option for many tumor types, especially for widely metastatic disease. To overcome the problem, researchers are now developing targeted TNF-α delivery systems. These involve either direct targeting of the TNF-α protein to the tumor and delivery by gene therapy. We recently reported the evaluation of a potential novel gene therapy for melanoma using a targeted adeno-associated virus-phage (AAVP) vector to deliver TNF-α in the mouse M21 human melanoma xenograft model. The AAVP vector targets gene products to tumor vasculature by using an alpha-v integrin ligand (termed RGD-4C) motif. There was a statistically significant reduction in tumor size in mice injected with the AAVP-TNF-α vector as compared with controls, with no evidence of systemic toxicity [8]. A pre-clinical trial of this treatment in 14 tumor-bearing pet dogs by the Comparative Oncology Trials Consortium (COTC) demonstrated safety and activity, thus paving the way for human trials [9].

Targeting the gastric vasculature

Whereas endothelial cells lining the blood vessels of normal tissue are quiescent, those of tumor blood vessels express or upregulate many different markers, receptors and antigens, such as proliferation markers, receptors for growth factors and antigens not yet fully characterized. Immunologic or other molecular means of targeting therapies to endothelial cells is a reasonable approach, therefore, as these cells are highly accessible to antibodies or lytic effector cells [10].

Several peptides that can home to particular types of cancer have been identified using phage-display technology, and hybrid molecules composed of peptides conjugated to bioactive agents have shown promise in the imaging, diagnosis and treatment of a variety of tumors in pre-clinical and clinical trials (see references in [7]). Homing peptides might also be used to deliver gene therapy vectors into tumors. For example, RGD (Arg-Gly-Asp)-containing synthetic peptides with a high affinity for αv integrins home to malignant melanomas and breast carcinoma [11]. Peptides containing the NGR (Asn-Gly-Arg) motif can recognize tumor neovasculature in various tumor types [12]. The homing peptide F3, a 31 amino acid peptide in the HMGN2 sequence, homes to HL-60 human leukemia cell xenograft tumors in vivo, and human MDA-MB-435 breast cancer cells [13].

Fan and colleagues [14] are the first to identify a peptide that targets human gastric cancer. In a previous study, the group identified a novel peptide, GX-1, which binds selectively to human gastric cancer vasculature. In their latest paper [7] they show that, when GX-1 is fused to recombinant mutant human TNF-α (rmh-TNF-α), the fusion protein concentrates the TNF-α in tumors of human gastric cancer cells grown in nude mice, delays their growth and causes less systemic toxicity than TNF-α alone [7]. The authors used rmh-TNF-α as it has been shown to display greater anti-tumor activity than unmodified TNF-α. In their current work, Chen et al. [7] also show that GX1 can act not only as a targeting vector but also as an anti-angiogenic agent in its own right, inhibiting the proliferation of tumor-conditioned human umbilical vein endothelial cells in culture by inducing apoptosis.

Endogenous inhibitors of angiogenesis

Pro-angiogenic cytokines work in concert with endogenous angiogenesis inhibitors to regulate tumor growth in certain locations. More than 40 endogenous angiogenesis inhibitors have been discovered in humans, more than 13 of which have been used in gene therapy models [15] (Table 2). Anti-angiogenic factors are not stable on their own and they are not cytotoxic, and to be effective they would require chronic administration. Anti-angiogenic factors could be made more reliable through the use of somatic gene therapy. The patient's own cells and tissues would be altered so as to produce increasing circulating concentrations of the anti-angiogenic agent [15].

Table 2.

Endogenous angiogenesis inhibitors

| Inhibitor | Molecular and physiologic properties |

| Proteolytic fragments | |

| Angiostatin | 38-kD internal fragment of plasminogen (kringles 1-4); kringles 1-3 and kringle 5 also active. |

| Arrestin | 26-kD carboxy-terminal noncollagenous domain of a1 chain of Type IV collagen; inhibits endothelial cell (EC) proliferation. |

| Antithrombin (cleaved) | 53-55-kD cleaved conformation inhibits EC proliferation and tumor growth in mice. |

| Canstatin | 24-kD carboxy-terminal noncollagenous domain of a2 chain of Type IV collagen; inhibits EC proliferation and apoptosis. |

| Endostatin | 20-kD fragment of carboxy-terminal noncollagenous domain of Type XVIII collagen; mechanism of action unknown. |

| Fibronectin fragments | 29-kD amino-terminal and 40-kD carboxy-terminal heparin-binding fragments inhibit EC proliferation. |

| PEX | Carboxy-terminal hemopexin-like domain of matrix metalloproteinase-2 inhibits EC proliferation and tumor growth in mice. |

| Prolactin (16-kD) | Naturally occurring 16-kD cleaved amino-terminal fragment of prolactin; retains activity as partial prolactin agonist. |

| Prothrombin kringle-2 | 22-kD prothrombin fragment initially isolated from lipopolysaccharide-treated serum. |

| Restin | 22-kD fragment of carboxy-terminal noncollagenous domain of Type XV collagen; 60% homology to murine endostatin. |

| Vasostatin | Amino-terminal fragment of calreticulin; inhibits EC proliferation and tumor growth in mice. |

| Interleukins | |

| IL-1 | 17-kD β-isoform inhibits FGF-stimulated angiogenesis by an autocrine pathway. |

| IL-4 | 13-kD lymphokine; inhibits basic FGF-induced angiogenesis. |

| IL-10 | Inhibits tumor vascularity and growth, possibly by decreasing macrophage-derived angiogenic factors. |

| IL-12 | 75-kD glycoprotein; inhibits in vivo angiogenesis via IFN-γ - and IP-10-related mechanism. |

| IL-18 | IFN-γ-inducing cytokine; inhibits FGF-stimulated EC proliferation and in vivo angiogenesis. |

| Interferons | |

| IFN-α | 8 to 20-kD glycoproteins secreted by lymphocytes and phagocytes; inhibits EC proliferation and migration. |

| IFN-β | 23-kD glycoprotein derived from fibroblasts and epithelial cells. |

| IFN-γ | 20 to 25-kD glycoprotein secreted by T cells and natural killer cells; cytotoxic to proliferating ECs. |

| TIMP metallopeptidase inhibitors | |

| TIMP-1 (TIMP metallo-peptidase inhibitor 1) | Soluble 8.5-kD collagenase inhibitor. |

| TIMP-2 | Soluble 21-kD collagenase inhibitor. |

| TIMP-3 | Extracellular matrix-associated collagenase inhibitor. |

| Other molecules | |

| 1,25-(OH)2-vitamin D3 | Antiangiogenic effect similar to that of retinoic acid; nonhydroxylated vitamin D3 not active. |

| 2-methoxyestradiol | 0.3-kD estrogen metabolite; inhibits EC migration and urokinase plasminogen activator. |

| Angiopoietin-2 | Inhibits angiopoietin-1-mediated activation of EC tyrosine kinase receptor, Tie2; role in vascular remodeling. |

| EMAP-II | Tumor-derived 20-kD (34 kD proform) inflammatory cytokine. |

| Gro-β | 8-kD CXC chemokine; inhibits tumor growth in mice. |

| IP-10 | 8.6-kD CXC chemokine induced by IFNγ -. |

| Maspin | 42-kD serine protease inhibitor (serpin); inhibits EC migration and tumor growth and vascularity in mice. |

| METH-1, METH-2 | 110- and 98-kD proteins with metalloprotease and disintegrin-like domains, and carboxy-terminal type 1 TSP-1 repeats. |

| MIG | 11.7-kD CXC chemokine induced by IFN-γ. |

| p16 | Tumor supressor gene; wild type downregulates VEGF expression and inhibits angiogenesis in gliomas. |

| p53 | Tumor suppressor gene; wild type increases TSP-1 expression, decreases VEGF expression. |

| PEDF | 50-kD inhibitor expressed by retinal pigment epithelial cells. |

| Platelet factor-4 | 28-kD heparin-binding platelet-derived inhibitory factor. |

| Proliferin-related protein | Inhibitor of placental angiogenesis in late gestation. |

| Prostate-specific antigen | Serine protease associated with prostate carcinoma and other tumors. |

| Protamine | 43-kD heparin-binding protein produced by sperm; role in vessel remodeling. |

| Retinoic acid | 0.3-kD inhibitor of EC migration; appears to act as transcriptional regulator. |

| Soluble FGF receptor | 60 to 85-kD circulating binding proteins that may regulate pro-angiogenic activity of FGF. |

| Transforming growth factor β1 | 25-kD inhibitor of EC growth and proteolytic activity. |

| Troponin I | Subunit of troponin complex recently found to be present in cartilage and to inhibit angiogenesis. |

| TSP-1, TSP-2 | 450-kD platelet- and fibroblast-derived trimeric glycoproteins. |

New approaches to cancer treatment such as drug targeting and gene therapy hold promise for more tailored approaches in the treatment of cancer. The more we learn about individual cancer cells and how they function within their microenvironment, the more therapeutic targets we will discover. We have seen that the identification of anti-angiogenesis targets opens up a wide new field of study. New areas of study, together with further research in gene therapy, will hopefully improve and prolong the lives of patients afflicted with cancer.

References

- Beacham DA, Cukierman E. Stromagenesis: The changing face of fibroblastic microenvironments during tumor progression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2005;15:329–341. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalluri R, Zeisberg M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:392–401. doi: 10.1038/nrc1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tlsty TD, Coussens LM. Tumor stroma and regulation of cancer development. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis. 2006;1:119–150. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouis D, Kusumanto Y, Meijer C, Mulder NH, Hospers GA. A review on pro- and anti-angiogenic factors as targets of clinical intervention. Pharmacol Res. 2006;53:89–103. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute http://www.cancer.gov/

- Szlosarek PW, Balkwill FR. Tumour necrosis factor a: a potential target for the therapy of solid tumours. Lancet Oncol. 2004;4:565–573. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(03)01196-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Shanshan C, Zhang Y, Wang X, Liu J, Hui X, Wan Y, Du W, Wang L, Wu K, Fan D. A novel peptide (GX1) homing to gastric cancer vasculature inhibits angiogenesis and cooperates with TNF alpha in anti-tumor therapy. BMC Cell Biol. 2009;10:63. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-10-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandle A, Hanna E, Lorang D, Hajitou A, Moya CA, Pasqualini R, Arap W, Adem A, Starker E, Hewitt S, Libutti SK. Tumor vasculature-targeted delivery of tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Cancer. 2009;115:128–139. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoloni MC, Tandle A, Mazcko C, Hanna E, Kachala S, Leblanc A, Newman S, Vail D, Henry C, Thamm D, Sorenmo K, Hajitou A, Pasqualini R, Arap W, Khanna C, Libutti SK. Launching a novel preclinical infrastructure: comparative oncology trials consortium directed therapeutic targeting of TNF alpha to cancer vasculature. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4972. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmeister V, Vetter C, Schrama D, Brocker EB, Becker JC. Tumor stroma-associated antigens for anti-cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2006;55:481–494. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0070-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasqualini R, Koivunen E, Ruoslahti E. Alpha v integrins as receptors for tumor targeting by circulating ligands. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:542–546. doi: 10.1038/nbt0697-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corti A, Curnis F, Arap W, Pasqualini R. The neovasculature homing motif NGR: more than meets the eye. Blood. 2008;112:2628–2635. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-150862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porkka K, Laakkonen P, Hoffman JA, Bernasconi M, Ruoslahti E. A fragment of the HMGN2 protein homes to the nuclei of tumor cells and tumor endothelial cells in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:7444–7449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062189599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhiu M, Wu KC, Dong L, Hao ZM, Deng TZ, Hong L, Liang SH, Zhao PT, Qiao TD, Wang Y, Xu X, Fan DM. Characterization of a specific phage-displayed peptide binding to vasculature of human gastric cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2004;3:1232–1235. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.12.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman AL, Libutti SK. Progress in antiangiogenic gene therapy of cancer. Cancer. 2000;89:1181–1194. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000915)89:6<1181::AID-CNCR1>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]