Abstract

Bacillus subtilis is one of the most studied gram-positive bacteria. In this work, YvgN and YtbE from B. subtilis, assigned as AKR5G1 and AKR5G2 of aldo-keto reductase (AKR) superfamily. AKR catalyzes the NADPH-dependent reduction of aldehyde or aldose substrates to alcohols. YvgN and YtbE were studied by crystallographic and enzymatic analyses. The apo structures of these proteins were determined by molecular replacement, and the structure of holoenzyme YvgN with NADPH was also solved, revealing the conformational changes upon cofactor binding. Our biochemical data suggest both YvgN and YtbE have preferential specificity for derivatives of benzaldehyde, such as nitryl or halogen group substitution at the 2 or 4 positions. These proteins also showed broad catalytic activity on many standard substrates of AKR, such as glyoxal, dihydroxyacetone, and DL-glyceraldehyde, suggesting a possible role in bacterial detoxification.

Keywords: aldo-keto reductase, (β/α)8 TIM barrel fold, heteroaromatic aldehyde, YtbE/YvgN

Introduction

Bacillus subtilis is a rod-shaped and endospore-forming, gram-positive, catalase-positive bacterium commonly found in soil.1 It is non-pathogenic, and has been proven highly amenable to genetic manipulation, and has, therefore, become widely adopted as a model organism for laboratory studies, especially for sporulation, which is a simplified example of cellular differentiation. The YvgN from B. subtilis is related to the sporulation formation and the YtbE is the essential gene of this bacteria.2,3 Both YvgN and YtbE belong to the aldo-keto reductase (AKR) superfamily.

Aldo-keto reductases (AKRs), typically having about 300 amino acids, fold into the (β/α)8 TIM-barrel shape. The AKR superfamily is one of the largest, composed of more than 120 widely distributed individual members belonging to 15 families4 (www.med.upenn.edu/akr/). In general, AKR catalyzes the NADPH-dependent reduction of different aldehyde or aldose substrates to their corresponding alcohols. Because of the pharmacological implications in diabetic complications and Vitamin C production, human aldehyde reductase (ALR1), aldose reductase (ALR2), and prokaryotic 2,5-diketo-d-gluconic acid (2,5-DKG) reductase have been extensively characterized. It is well known that AKRs use NADPH as a hydride donor. A tetrad of conserved residues, consisting of tyrosine, histidine, aspartate, and lysine, is essential for the hydrogen transfer reaction.5,6 The overall fold is well conserved in all AKRs, remarkable alterations occur in several regions, including the C-terminal region, loops β7 and β3, which are important for substrate and NADPH binding.7 Studies of human ALR inhibitors have shown that the substrate binding pocket can adapt to various conformations according to the corresponding inhibitor, which causes adverse side effects and failure of many drug candidates.8

On the basis of sequence alignment, YvgN and YtbE from B. subtilis have been assigned as AKR5G1 and AKR5G2, respectively, belonging to the AKR5 family. The AKR5 family so far consists of 11 individual proteins, three of which are structurally known. Members in the AKR5C to AKR5E subfamilies are known as 2,5-DKG reductase, especially the Corynebacterium-derived AKR5C1, which has been well characterized due to its function in the commercial production of vitamin C.9 Structural and mutational analysis of AKR5A2 from Trypanosoma brucei has revealed that it is a specific prostaglandin H2 reductase.10 As for YvgN and YtbE, these two proteins share ∼70% sequence identity, and homologous proteins have also been found in the pathogen Bacillus anthracis [Fig. 1(A)]. Both proteins are involved in osmotic regulation.11 YvgN is necessary as an extracellular protein for sporulation formation in B. subtilis.2,3 Enzymatic studies of recombinant YvgN with an N-terminal GST tag indicate its broad catalytic activities for DL-glyceraldehyde, methylglyoxal, and glyoxal.12 Although YtbE is verified as an essential gene of B. subtilis by DNA disruption,3 to date, knowledge of YtbE is very limited.

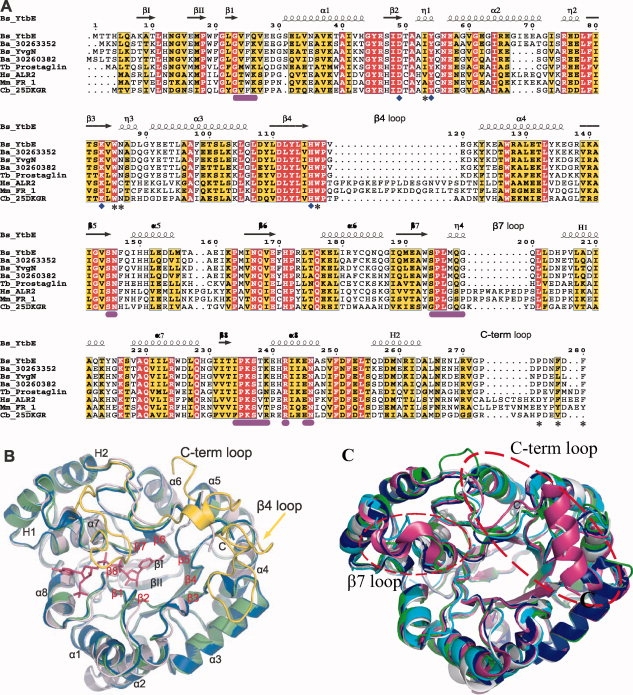

Figure 1.

Overall structures of YtbE and YvgN. (A) Structure based multiple sequence alignment of AKRs from different species. YtbE and YvgN from B. subtilis (Bs), ALR2 from H. sapiens (Hs), FR-1 from M. musculus (Mm), and 2,5-DKGR from Corynebacterium (Cb) labeled by abbreviations of species and protein names. Sequence accession (gi) numbers of two proteins from B. anthracis are shown. Highly conserved and conserved residues are colored red and yellow, respectively. Residues involved in cofactor binding and substrate binding are labeled by purple bars and asterisks below the sequences, respectively. Residues forming the conserved catalytic tetrad are indicated by diamonds. Secondary structural elements are drawn according to the solved structures described in this report. (B) Ribbon diagrams of apo YtbE, apo YvgN, holo YvgN, colored in salmon, blue, and green, respectively. The bound NADPH in holo YvgN is shown by sticks. Three long loops of FR-1 from M. musculus, following β4, β7, and H2, are selected and shown in yellow, with the residual structure of FR-1 not visible. (C) Comparing the apo YtbE and apoYvgN with other known structures in AKR5 family. The apo YtbE is salmon, apo YvgNis blue, holo 2,5-DKG reductase with NADPH (PDB ID: 1A80) in Corynebacterium is green, holo 2,5-DKG reductase with NADP (PDB ID: 1VP5) in Thermotoga maritime is purple, and apo 2,5-DKG reductase (PDB ID: 1MZR) in E. coli is cyan. The two red cycles display the β7 loop and C-terminal loop.

In this report, the first crystal structures of AKR5G1 (apo YvgN), AKR5G2(apo YtbE) family has been described, and the structure of the holo YvgN, in addition to their biochemical activities, are also extensively described. The biochemical and structural results extend our understanding of AKR proteins and provide insight into the possible in vivo functions of YvgN and YtbE.

Results and Discussion

Structure determination

In one asymmetric unit of the apo YvgN crystal, a “face-to-face” crystallographic dimmer was found, with the substrate binding pockets interacting with each other. The holoenzyme YvgN:NADPH had the same crystallographic parameters and arrangement as apoYvgN. In the asymmetric unit of YtbE, three chemically identical monomers were observed, and the root mean square deviation (RMSD) between these monomers was less than 0.4 Å, with all of the Cα atoms aligned. However, from the gel-filtration chromatography, both YvgN and YtbE in solution were determined to be monomers, which are believed to be the functional units in vivo. The final refinement statistics and other crystallographic properties are listed in Table I.

Table I.

Crystallographic and Refinement Statistics

| PDB code | 3B3D | 3F7J | 3D3F |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | Apo YtbE | Apo YvgN | Holo YvgN |

| Space group | P212121 | P21212 | P21212 |

| Cell dimensions | |||

| a, b, c (Å) | 83.11, 89.17, 115.69 | 79.6, 123.1, 57.2 | 80.5, 123.3, 57.2 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 |

| Wavelength | 1.2579 | 0.96 | 1.54 |

| Resolution (Å) | 2.30 (2.30–2.36) | 1.70 (1.79–1.70) | 2.40 (2.46–2.40) |

| Rsym or Rmerge | 12.1 (38.7) | 6.4 (49.3) | 6.8 (36.9) |

| I/σI | 20.0 (4.8) | 9.3 (1.6) | 15.0 (2.3) |

| Completeness (%) | 97.2 (100) | 94.5 (96.2) | 95.9 (97.7) |

| Redundancy | 9.4 (9.6) | 5.3 (5.2) | 2.7 (2.6) |

| Refinement | |||

| Resolution (Å) | 2.3 | 1.7 | 2.4 |

| No. of reflections | 35898 | 58185 | 33562 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.20/0.26 | 0.21/0.25 | 0.22/0.31 |

| No. of atoms | |||

| Protein | 6807 | 4480 | 4449 |

| NADPH | — | — | 96 |

| Water | 256 | 528 | 145 |

| B-factors | |||

| Protein | 25.3 | 18.0 | 22.6 |

| NADPH | — | — | 20.9 |

| Water | 23.4 | 26.4 | 34.5 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.018 | 0.019 | 0.019 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.73 | 1.75 | 1.99 |

Overall structures of YvgN and YtbE

YvgN and YtbE share high sequential and structural similarity (the RMSD of the Cα atoms of monomers was 0.9 Å), and the main differences were at the C-terminal ends of the β/α parallel barrel shapes [Fig. 1(B)]. On the basis of the knowledge of (β/α)8 TIM-barrel proteins, the first two N-terminal β strands sitting over the central β-barrel and two C-terminal helices beyond the barrel were designated as βI, βII, and H1, H2, respectively [Fig. 1(A,B)]. The core helices and strands were sequentially numbered 1 through 8, and loops were given the same number as the strand it followed. The helix H1 preceded α7, and H2 followed α8. Following H2, the C-terminal 26 residues spanned the top of the barrel, contributing to the substrate binding [Fig. 1(A,B)].13 Using any of our structures as the query input in the Dali server,14 FR-1 from Mus musculus ranked at the top, with the RMSD less than 1.5 Å and the Z-score higher than 35. As shown in Figure 1(B), the remarkable differences between our structures and FR-1, a typical eukaryotic AKR, were loops β4 and β7, which define the substrate binding pocket and NADPH binding pocket, respectively [Fig. 1(B)]. In addition, the C-terminal loops were much shorter in YvgN and YtbE than in eukaryotic AKRs. Until now, the other members of AKR5 family with known structure are apo 2,5-DKG reductase (PDB ID: 1HW6) and holo 2,5-DKG reductase with NADPH (PDB ID: 1A80) in Corynebacterium, holo 2,5-DKG reductase with NADP (PDB ID: 1VP5) in Thermotoga maritime, and apo 2,5-DKG reductase (PDB ID: 1MZR) in E. coli. Because 1HW6 missed the C-terminal sequences, we compared YvgN and YtbE with 1A80, 1VP5, and 1MZR, and found that 1VP5 has a large different in the β7 loop and C-terminals between these proteins [Fig. 1(C)]. The β7 loop of YvgN and YtbE are instead of η helix in 1VP5. The C-terminal of 1VP5 is formed one α helix while that of YtbE and YvgN are loops. The C-terminal loop of 1A80 is longer than that of YvgN and YtbE. As for 1MZR, only comparing the structures with YvgN and YtbE, there is no dramatic difference on the β7 loop and C-terminal.

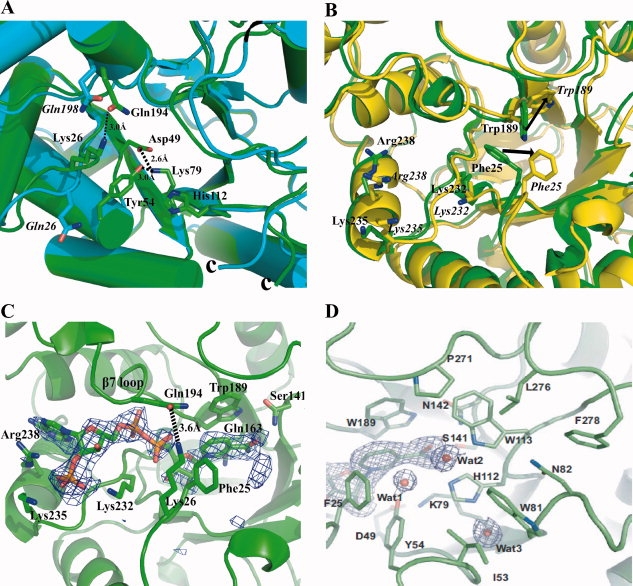

The safety belt

In most of the structurally known members of the AKR superfamily, loops βl and β7 directly interact with each other through hydrogen bonding, forming a “safety belt” holding the pyrophosphate moiety of the cofactor.15 A conformational change of the safety belt for releasing NADP+ is believed to be rate-limiting in all AKRs.16 In YvgN, the safety belt was stabilized by a hydrogen bond between Lys-26 and Gln-194 [Fig. 2(A)], but no significant conformational change occurred in the safety belt upon NADPH binding. In contrast, the residue corresponding to Lys-26 in YvgN is absent from YtbE [It is Gln26, shown in italics, Fig. 2(A)], no safety belt was observed.

Figure 2.

Analysis of the structures of YvgN and YtbE. (A) Safety belt and catalytic tetrad in YvgN and YtbE. YvgN is green and YtbE is cyan. The residues of YtbE are in italics. (B) Superimposition of apo and holo YvgN. The apo YvgN is green and holo YvgN is yellow. The residues of holo YvgN are in italics, the arrow shows the residues movement between the apo and holo YvgN. (C) Cofactor binding site of holo-YvgN with simulated annealed omit map. NADPH binding in YvgN with the Fo−Fc omit map (σ = 2.0) was colored in blue and the safety belt formed by Lys-26 and Gln-194 was indicated by a black dashed line. (D) Putative substrate binding site of YvgN. Three water molecules regarding the orientation of substrates are shown with the 2Fo−Fc density map (σ = 1.0).

Catalytic tetrad

As shown in Figure 2(A), in addition to the conserved fold, four strictly conserved catalytic residues, Tyr-54 (54), Lys-79 (83), Asp-49 (49), and His-112 (116) [relevant YtbE residues number are in parentheses. To be clear, we only show the catalytic tetrad of YvgN in Fig. 2(A), the YtbE is the similar situation], occurred in all of our structures and were designated as the catalytic tetrad, whose importance was confirmed previously.5 A conserved hydrogen bonding network between the catalytic tetrad residues occurred in YvgN and YtbE [Fig. 2(A)]. For YvgN, Lys-79 was linked to the carboxylate of Asp-49 by salt bridges, and the amine side chain of the lysine also interacted with the phenolic hydroxyl group of Tyr-54 through hydrogen bonding, which has been postulated depress the pKa of tyrosine and enable it to act as an acid to facilitate the hydrogen transfer to the substrate.15 The His-112 was buried in a hydrophobic environment, composed of Ile-53, Trp-81, and Trp-113. This environment would not favor the formation of a charged imidazolium group, and thus, the abstraction of a proton. As to the function of His-112, instead of donating a proton, it is believed to be essentially related to the orientation of the substrate carbonyl in the active site.10,17,18 So, the process of the catalytic tetrad in the YvgN could be described as below: the acidity of the Tyr-54 is enhanced by a hydrogen bond with the Lys-79, which in turn forms a salt bridge with the Asp-49, then the Try-54 easily apply the proton taking part in the reaction; while the His-112 could be related to the substrate.

Comparison of apo and holo YvgN

No shift in secondary structures occurred upon NADPH binding. Remarkable conformational changes mainly involved only the residues around the cofactor binding pocket [Fig. 2(B) residues of holo YvgN are in italics]. The RMSD between the Cα atoms of apo and holo YvgN was 0.5 E. Lys-232, Lys-235, and Arg-238 were reoriented to form hydrogen bonds with the 2′-phosphate of the NADPH cofactor [Fig. 2(B,C)]. Trp-189 and Phe-25 had to move out of the way to provide a pocket for the cofactor binding, which caused the indole ring to stack almost completely in parallel with the nicotinamide ring of the cofactor.

NADPH binding pocket of YvgN

The structure of the holoenzyme YvgN revealed that the NADPH was bound in an extended conformation, starting from the center of the barrel, where the nicotinamide ring and the active site resided. The binding pocket was formed by loops β1, β7, β8, and helix α8, with residues 189–194 on one side and 24–26, 232–242, and the main-chain carbonyl of Asp-46 on the opposite side. Besides the safety belt described above, the bound cofactor was also tightly stabilized by a hydrogen bonding network [Figs. 2(C) and 3].

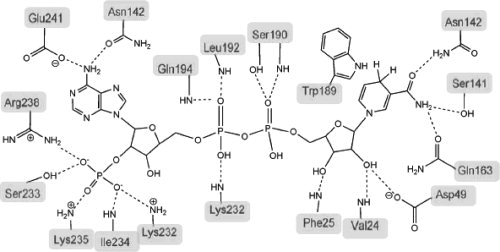

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the interactions between NADPH and YvgN. Hydrogen bonds and salt bridges shown by dashed lines, and the indole ring of Trp-189 is involved in the aromatic stacking interaction with the nicotinamide ring of the bound NADPH.

The adenine group of the NADPH threaded between α8 and loop β7, thus the side chain of Arg-238, which was linked with the 2′ phosphate via a hydrogen bond, extended parallel to the inserted group. Lys-232 and Lys-235 also contributed directly to the positively charged environment for a hydrogen bonding network between the 2′ phosphate and the protein. The pyrophosphate group was held in place by five main-chain amide groups of residues 24, 25, 192, 194, and 232 (see Fig. 3). The nicotinamide of the NADPH and its ribose ring were positioned deep in the center of the eight parallel strands. The A face of the nicotinamide ring formed hydrophobic stacking interactions with Trp-189,19 and the NH2 group interacted with side chains of Ser-141 and Gln-163 via hydrogen bonds. The hydrogen bonding network of the nicotinamide ring caused YvgN to suggest the possible conformation for hydride transferring. As described above, Phe-25 was reoriented away from the central region of the barrel to prevent static clash with the bound cofactor. The other role of the phenylalanine in this position appeared to be spatially determining the conformation of the ribose ring of the nicotinamide.

Substrate binding pocket

On the basis of the previous studies of AKRs, residues on the C-terminal loop are necessary for substrate reduction.7,13 Compared with eukaryotic AKRs, the C-terminal loop and loop β7, designating the substrate binding pocket, were much shorter in YvgN and YtbE, even though the C-terminal loop spanned back over the top of the barrel. For YvgN, the putative substrate binding pocket was mainly composed of the aromatic and apolar residues Phe-25, Ile-53, Tyr-54, Lys-79, Trp-113, Trp-81, His-112, Asn-82 and some hydrophobic residues at the C-terminal loop, Pro-269, Leu-274, and Phe-276 [Fig. 2(D)]. Because of its location, the C-terminus (residues 271-277) is believed to be involved in substrate binding.

In addition, the substrate binding pocket of YvgN was characterized by the presence of three water molecules, Wat1, Wat2, and Wat3, all of which showed low B-factors (25.1, 21.3, and 12.8, respectively). Those water molecules formed three hydrogen bonds with Tyr-54OH, Trp-113Nɛ1, and His-112Nδ1 groups [Fig. 2(D)]. Especially, the protonation state of the His-112 might affect the orientation of the carbonyl groups of the putative substrates during the reactions.17

Enzyme kinetics

The catalytic process of YvgN and YtbE most likely constitutes an ordered “bi–bi” mechanism as that of other AKRs,20,21 in which the NADPH would bind first and the substrate binding and reduction would then be facilitated by the conformational changes on the cofactor binding.

Both YvgN and YtbE reduced the common AKR substrates, such as DL-glyceraldehyde, benzaldehyde, dihydroxyacetone, methylglyoxal, and butyraldehyde. Among the potential substrates tested, these two proteins showed remarkably specificity for the heteroaromatic aldehydes, such as 4-nitrobenzaldehyde (Table II). Replacement of the 4-nitryl group by a 4-chloride or a 3-nitryl, sharply reduced the catalytic efficiency of both enzymes, similar to human ALR1 and ALR2.22,23 Moreover, substitution of the 4-nitryl or 4-halogen group by a 2-halogen showed 10-fold to 200-fold more activity. It has also been shown previously in ALR1 that Arg-311, positioned on the C-terminal loop and orientated to the substrate binding pocket, determines the substrate specificity via hydrogen bonds with negatively charged groups on the substrate.13 However, such an arginine or any amide group with similar character was absent from the C-terminal loops of YvgN and YtbE, in which several conserved hydrophobic residues were orientated to the substrate binding pockets. In addition, Asn-82YvgN or Asn-86YtbE is highly conserved among the prokaryotic AKRs [Fig. 1(A)], thus, these Asn residues may determine the substrate specificity by interacting with the 4-group of the aromatic ring. On the basis of the catalytic efficiency of tested substrates, YvgN showed substrate specificities similar to YtbE, consistent with the structural data.

Table II.

Enzymatic Assay Results for Various Substrates

| YtbE |

YvgN |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrates | Km (mM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (s−1 mM−1) | Km (mM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (s−1 mM−1) |

| Benzaldehyde | 1.62 | 1.79 | 1.10 | 1.43 | 1.13 | 0.79 |

| 4-Nitrobenzaldehyde | 0.20 | 6.31 | 31.55 | 0.30 | 17.37 | 57.12 |

| 3-Nitrobenzaldehyde | 4.62 | 13.95 | 3.02 | 2.42 | 13.50 | 5.57 |

| 2-Nitrobenzaldehyde | 0.41 | 17.85 | 43.54 | 0.31 | 25.69 | 81.66 |

| 4-Chlorobenzaldehyde | 1.27 | 1.55 | 1.22 | 2.01 | 8.65 | 4.30 |

| 3-Chlorobenzaldehyde | 5.45 | 26.18 | 4.80 | 14.67 | 40.77 | 2.78 |

| 2-Chlorobenzaldehyde | 0.12 | 46.11 | 373.32 | 0.086 | 43.37 | 503.73 |

| 2,4-Dichlorobenzaldehyde | 0.21 | 71.70 | 363.09 | 0.055 | 40.86 | 740.30 |

| 2,4-Dinitrobenzaldehyde | 0.16 | 16.52 | 104.29 | 0.082 | 18.32 | 222.65 |

| 3,4-Dichlorobenzaldehyde | 2.66 | 16.72 | 6.29 | 2.96 | 24.64 | 8.32 |

| 2,3-Dichlorobenzaldehyde | 0.24 | 65.19 | 271.64 | 0.34 | 32.76 | 95.94 |

| 4-Tolualdehyde | 9.68 | 13.96 | 1.44 | 0.51 | 2.18 | 4.31 |

| 2-Tolualdehyde | 2.50 | 59.83 | 23.90 | 1.56 | 30.95 | 19.88 |

| Methylglyoxal | 2.44 | 0.64 | 0.26 | 4.77 | 6.27 | 1.31 |

| DL-glyceraldehyde | 2.38 | 1.31 | 0.55 | 6.27 | 9.89 | 1.58 |

| Glyoxal | 2.95 | 6.35 | 2.15 | 1.39 | 9.04 | 6.51 |

In addition to catalyzing the reduction of aldehyde or aldose to the corresponding alcohols, some members of the AKR superfamily work in the reverse reaction. YvgN and YtbE were thus tested for dehydrogenase activity using NADP+ as the hydride acceptor. Several compounds were tried, including pyridoxal, d-arabinose, l-xylose, glucose, and fructose. However, neither enzyme showed any detectable activity, suggesting that neither YvgN nor YtbE act as a dehydrogenase.

In conclusion, on the basis of the specificities on heteroaromatic aldehydes and broad substrate activity revealed in this report, both YvgN and YtbE can detoxify various aldehydes derived from bacterial stress, including DL-glyceraldehyde, methylglyoxal and dihydroxyacetone, which can be formed under extreme conditions. Specific biological functions in vivo for many AKRs have not yet been clearly identified, and this is the case for YvgN and YtbE as well, it is hoped that the high precision structural and biochemical information provided by this study will inspire ideas and interests in the physiological studies of this big family of enzymes. Further studies are necessary to unambiguously elucidate and validate the functions of YvgN and YtbE in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Cloning, expression and protein purification

Recombinant YvgN and YtbE were generated by similar methods, so no gene or protein name is specified in this section. Gene fragments were PCR-amplified from B. subtilis strain 168 genome DNA, with BamHI and XhoI restriction sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. The specifically digested gene fragments were inserted into linear pET28a, and the ligation was verified by DNA sequencing. The recombination protein include His tag proceeded the native protein. The extra residues are “MGSS HHHHHH SSG LVPRGS HMASMTGGQQMGRGS” (the “LVPRGS” is the thrombin site). The final constructs were transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) for protein production. Single colonies were cultured overnight at 310 K in 20 mL Luria-Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with 50 mg mL−1 kanamycin, and then the overnight culture was transferred to 1 liter LB. When OD600 of the culture reached 1.0, 0.5 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside was added to induce protein expression. After another 2 h in culture at 310 K, bacteria were harvested and resuspended in 20 mM Tris pH 7.5 and 500 mM NaCl. Bacterial cells were broken by ultrasonication, and the lysate was centrifuged at 45000g for 30 min at 277 K. Supernatant was loaded onto a 5 mL Hitrap nickel column (GE-Healthcare), which was pre-equilibrated by the resuspension buffer. Impurities were washed out by suspension buffer supplemented with 60 mM imidazole, and the target protein was eluted by increasing imidazole to 250 mM. For gel-filtration chromatography, a 120 mL Superdex 75 column (GE-Healthcare) was used, and the elution buffer was 20 mM Tris pH 7.5 and 200 mM NaCl.

Analytical gel-filtration chromatography and crystallization

Oligomerization of purified YvgN and YtbE were checked with a 24 mL HR 10/30 Superdex 75 column (GE-Healthcare) in the same buffer as previously used for gel-filtration, and the molecular weights were calibrated according to Bio-rad standards (BioRad). The purified proteins were concentrated by a 10 kD cutoff protein concentration device (Millipore), and the final concentrations for crystallization of both YvgN and YtbE were about 0.5 mM, which was confirmed by Bradford protein assay (BioRad). Crystallization trials were carried out at 289 K by the hanging drop vapor-diffusion methods with 1uL of protein and 1uL of reservoir. For YtbE, crystals were obtained in the 50 mM Bis-Tris pH 6.5, 50 mM calcium chloride, and 20% v/v PEGMME550 first and then optimized. Finally, the crystals suitable for data collection were obtained under 50 mM Bis-Tris pH 6.3, 50 mM calcium chloride, and 15–20% v/v PEGMME550. For YvgN, crystals were obtained under 0.1M Tris pH 7.5, 0.4M sodium nitrate, and 40% w/v PEG3350 and suitable for data collection. For holoenzyme of YvgN, crystals of apo protein were soaked overnight in the mother liquid containing 5 mM NADPH.

Data collection, structure determination, and refinement

Crystals were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen before mounting. For apo YtbE, a data set was collected at the Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility (BSRF) 3W1A beamline at 100 K using a Mar165 CCD detector. The data set was processed by the HKL program package.24 For apo YvgN, a whole data set was collected at the BW7A beamline of EMBL Hamburg at the DORIS storage ring of the “Deutsches Elektronen Synchrotron” DESY (Hamburg, Germany), and the data integration and scale were performed using Mosflm and Scala (1994). The data set of the holo YvgN was collected at 100 K on a Bruker in house X-ray machine of copper rotating anode equipped with a SMART6000 CCD detector. The in-house data set was processed using the on-line Bruker Proteum package. The data collection and processing statistics of those three data sets are summarized in Table I.

Apo YtbE and YvgN structures were solved by molecular replacement, using the coordinates of AKR5A2 (PDB ID: 1VBJ) as the search model in the MOLREP program.25,10 Simulated annealing in the program suite CNS26 was used in the beginning of the refinement, and further refinement and manual building were performed in COOT27 and REFMAC5.25 When the Rfree dropped below 30%, NCS restraint was released and TLS refinement28 was carried out, then solvent molecules were built into the Fo−Fc density map. Coordinates of apo YvgN were used to solve the structure of the holoenzyme, with the same set of free-R flags. After a few rounds of restrained refinement in REFMAC5, water molecules, cofactor, and ligand were located in the Fo−Fc density. The coordinates were deposited in the Protein Data Bank, with the PDB access codes 3B3D (apo YtbE), 3F7J (apo YvgN), and 3D3F (holoenzyme YvgN).

Enzymatic activity assay

YvgN and YtbE activities in purified fractions were determined using 0.24 mM NADPH as previously described.5 The decrease in absorbance at 340 nm was monitored by a SHIMADZU UV-2450 machine at 298 K. Reactions were carried out in a 600 μL system containing 50 mM potassium phosphate, 10 mM KC1, and 0.5 mM EDTA at pH 7.0, with different concentration ranges of various substrates. The reactions were started by addition of enzyme, and all reactions were carried out at least in duplicate. The Km and kcat values were determined by fitting the initial steady-state velocity data to the Michaelis-Menten equation using the software package UVProbe.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Yuhui Dong, Peng Liu, and Santosh Panjikar for help during their data collection efforts in the BSRF and the EMBL-Hamburg DESY ring beamlines. They thank Prof. Lars Hederstedt for his helpful discussion and comments on the manuscript. X.-D.S. was a recipient of the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars.

References

- 1.Nakano MM, Zuber P. Anaerobic growth of a “strict aerobe” (Bacillus subtilis) Annu Rev Microbiol. 1998;52:165–190. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.52.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antelmann H, Tjalsma H, Voigt B, Ohlmeier S, Bron S, van Dijl JM, Hecker M. A proteomic view on genome-based signal peptide predictions. Genome Res. 2001;11:1484–1502. doi: 10.1101/gr.182801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomaides HB, Davison EJ, Burston L, Johnson H, Brown DR, Hunt AC, Errington J, Czaplewski L. Essential bacterial functions encoded by gene pairs. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:591–602. doi: 10.1128/JB.01381-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hyndman D, Bauman DR, Heredia VV, Penning TM. The aldo-keto reductase superfamily homepage. Chem Biol Interact. 2003;143–144:621–631. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(02)00193-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tarle I, Borhani DW, Wilson DK, Quiocho FA, Petrash JM. Probing the active site of human aldose reductase. Site-directed mutagenesis of Asp-43, Tyr-48, Lys-77, and His-110. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:25687–25693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ehrensberger AH, Wilson DK. Structural and catalytic diversity in the two family 11 aldo-keto reductases. J Mol Biol. 2004;337:661–673. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bohren KM, Grimshaw CE, Gabbay KH. Catalytic effectiveness of human aldose reductase. Critical role of C-terminal domain. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:20965–20970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Kabbani O, Podjarny A. Selectivity determinants of the aldose and aldehyde reductase inhibitor-binding sites. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:1970–1978. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6514-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson S, Marks CB, Lazarus R, Miller J, Stafford K, Seymour J, Light D, Rastetter W, Estell D. Production of 2-Keto-L-Gulonate, an intermediate in L-ascorbate synthesis, by a genetically modified Erwinia herbicola. Science. 1985;230:144–149. doi: 10.1126/science.230.4722.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kilunga KB, Inoue T, Okano Y, Kabututu Z, Martin SK, Lazarus M, Duszenko M, Sumii Y, Kusakari Y, Matsumura H, Kai Y, SugiYama S, Inaka K, Inui T, Urade Y. Structural and mutational analysis of Trypanosoma brucei prostaglandin H2 reductase provides insight into the catalytic mechanism of aldo-ketoreductases. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:26371–26382. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413884200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biaudet-Brunaud V, Samson F, Gas S, Dervyn E, Gallezot G, Duchet S, Ehrlich SD, Bessières P. List of Bacillus subtilis unknown genes with a phenotype determined by the functional analysis project. In: Wolfgang S, Dusko Ehrlich S, Ogasawara N, editors. Functional analysis of bacterial genes: a practical manual. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakai A, Katayama K, Katsuragi T, Tani Y. Glycolaldehyde-forming route in Bacillus subtilis in relation to vitamin B6 biosynthesis. J Biosci Bioeng. 2001;91:147–152. doi: 10.1263/jbb.91.147. 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barski OA, Gabbay KH, Bohren KM. The C-terminal loop of aldehyde reductase determines the substrate and inhibitor specificity. Biochemistry. 1996;35:14276–14280. doi: 10.1021/bi9619740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holm L, Kaariainen S, Rosenstrom P, Schenkel A. Searching protein structure databases with DaliLite v. Bioinformatics. 2008:3. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson DK, Bohren KM, Gabbay KH, Quiocho FA. An unlikely sugar substrate site in the 1.65 A structure of the human aldose reductase holoenzyme implicated in diabetic complications. Science. 1992;257:81–84. doi: 10.1126/science.1621098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grimshaw CE, Bohren KM, Lai CJ, Gabbay KH. Human aldose reductase: rate constants for a mechanism including interconversion of ternary complexes by recombinant wild-type enzyme. Biochemistry. 1995;34:14356–14365. doi: 10.1021/bi00044a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Winter HL, von Itzstein M. Aldose reductase as a target for drug design: molecular modeling calculations on the binding of acyclic sugar substrates to the enzyme. Biochemistry. 1995;34:8299–8308. doi: 10.1021/bi00026a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson DK, Nakano T, Petrash JM, Quiocho FA. 1.7 A structure of FR-1, a fibroblast growth factor-induced member of the aldo-keto reductase family, complexed with coenzyme and inhibitor. Biochemistry. 1995;34:14323–14330. doi: 10.1021/bi00044a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rose IA, Hanson KR, Wilkinson KD, Wimmer MJ. A suggestion for naming faces of ring compounds. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:2439–2441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.5.2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Askonas LJ, Ricigliano JW, Penning TM. The kinetic mechanism catalysed by homogeneous rat liver 3 alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. Evidence for binary and ternary dead-end complexes containing non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Biochem J. 1991;278(Part 3):835–841. doi: 10.1042/bj2780835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deyashiki Y, Tamada Y, Miyabe Y, Nakanishi M, Matsuura K, Hara A. Expression and kinetic properties of a recombinant 3 alpha-hydroxysteroid/dihydrodiol dehydrogenase isoenzyme of human liver. J Biochem. 1995;118:285–290. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wermuth B, Munch JD, von Wartburg JP. Purification and properties of NADPH-dependent aldehyde reductase from human liver. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:3821–3828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morjana NA, Flynn TG. Aldose reductase from human psoas muscle. Purification, substrate specificity, immunological characterization, and effect of drugs and inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:2906–2911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymology. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vagin A, Teplyakov A. MOLREP: an automated program for molecular replacement. J Appl Crystallogr. 1997;30:1022–1025. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winn MD, Isupov MN, Murshudov GN. Use of TLS parameters to model anisotropic displacements in macromolecular refinement. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2001;57:122–133. doi: 10.1107/s0907444900014736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]