Abstract

Background

Panicum streak virus (PanSV; Family Geminiviridae; Genus Mastrevirus) is a close relative of Maize streak virus (MSV), the most serious viral threat to maize production in Africa. PanSV and MSV have the same leafhopper vector species, largely overlapping natural host ranges and similar geographical distributions across Africa and its associated Indian Ocean Islands. Unlike MSV, however, PanSV has no known economic relevance.

Results

Here we report on 16 new PanSV full genome sequences sampled throughout Africa and use these together with others in public databases to reveal that PanSV and MSV populations in general share very similar patterns of genetic exchange and geographically structured diversity. A potentially important difference between the species, however, is that the movement of MSV strains throughout Africa is apparently less constrained than that of PanSV strains. Interestingly the MSV-A strain which causes maize streak disease is apparently the most mobile of all the PanSV and MSV strains investigated.

Conclusion

We therefore hypothesize that the generally increased mobility of MSV relative to other closely related species such as PanSV, may have been an important evolutionary step in the eventual emergence of MSV-A as a serious agricultural pathogen.

The GenBank accession numbers for the sequences reported in this paper are GQ415386-GQ415401

Background

Panicum streak virus (PanSV) is one of seven known African streak virus species within the Mastrevirus genus of the Geminiviridae. The best studied and most economically relevant species amongst the African streak viruses is Maize streak virus (MSV) which seriously constrains maize production throughout most of sub-Saharan Africa [1]. Like MSV, African streak virus species such as Panicum streak virus (PanSV), Sugarcane streak virus (SSV), Sugarcane streak Reunion virus (SSRV) and Sugarcane streak Egypt virus (SSEV) are transmitted by various leafhopper species in the genus Cicadulina and have geographical ranges that are apparently restricted to Africa and its neighboring islands [1-7].

Whereas African streak virus species such as Eragrostis streak virus (ESV), Saccharum streak virus (SacSV), Urochloa streak virus (USV) and SSEV have been relatively poorly sampled and have therefore only ever been found in individual African countries [2,8-10], better sampling of MSV and PanSV has indicated that these species occur throughout sub-Saharan Africa [11,12]. PanSV and MSV display similar degrees of genetic diversity characterized by the existence of multiple discrete strains, many of which have distinctive geographical ranges [11,12]. Both species also have what appear to be largely overlapping host ranges. Unlike MSV, however, PanSV has no known economic relevance in that it has only ever been found in nature infecting wild grass species in the genera Urochloa, Ehrharta and Panicum [3,11,13].

Despite it not having any direct impact on African agriculture, the diversity and phylogeography of PanSV could still provide potentially useful information on other more economically important African streak viruses such as those that cause maize and sugarcane diseases. For example a recent comparative phylogeographic analysis of different MSV strains has indicated that the economically relevant maize adapted MSV-A strain is probably moving around Africa more freely than the closely related but Digitaria adapted MSV-B strain [12]. Comparative analyses of the diversity and phylogeography of different African streak virus species could therefore help identify the characteristics of MSV that facilitated its emergence as an important agricultural pathogen.

It has also been determined that African streak virus species such as PanSV have contributed indirectly to the evolution of MSV through genetic recombination [11,14]. Recombination is a major force in geminivirus evolution [15,16] and it appears to have played at least some role in the emergence of a number of serious geminiviral crop diseases [17-22]. At least seven of the eleven currently described MSV strains (including the important MSV-A strain) have apparently come into existence through recombination between two or more other strains [12]. It would be of great interest to determine whether such inter-strain recombination has featured as prominently in the diversification of other African streak viruses such as PanSV.

Here we use 23 full PanSV genome sequences sampled throughout Africa and one of its neighboring islands to show that there generally exist very similar patterns of diversity, recombination and geographical structure within PanSV and MSV populations. Our results indicate, however, that the maize adapted MSV-A strain is possibly unique amongst PanSV and MSV strains in both its total geographical range and the rates at which individual virus variants within the strain are moving across Africa.

Results and discussion

Discovery of five new PanSV strains

Sixteen full mastrevirus genome sequences were cloned and sequenced from Brachiaria deflexa, Panicum maximum, Panicum trichocladium, Urochloa maxima and Ehrharta calycina plants sampled from South Africa, Mozambique, Kenya, Nigeria, the Central African Republic and the Indian Ocean island of Mayotte (Table 1). All shared greater than 80% genome-wide identity with PanSV genomes currently deposited in public databases and were therefore all classified as being PanSV isolates. After confirming that plots of pairwise genetic similarity between all fully sequenced PanSV genomes closely matched those previously determined for MSV (Additional file 1), we used the 93% identity rule that has been used as a MSV strain demarcation criterion [14] to tentatively classify the PanSV isolates. This 93% identity threshold represents a logical, if not natural cutoff for classifying MSV and PanSV strains (Additional file 1) and it indicated that amongst the new sequences there potentially existed five new PanSV-strains (named PanSV-E to -I; Figure 1). It should be noted, however, that this classification scheme relied on the use of similarity measurements that exclude alignment gaps as missing data. Many other geminivirus classification schemes, such as the 75% and 89% thresholds endorsed by the ICTV for respectively demarcating mastrevirus and begomovirus species [23], do not specify how alignment gaps should be handled during similarity measurements. If we had included alignment gaps as a fifth character state - as is often done either accidentally or by design when arguments are made for or against new isolates being considered as new species - the 93% MSV/PanSV strain demarcation threshold would drop to between 90 and 91%.

Table 1.

Accession numbers and sampling coordinates of various mastrevirus isolates used to detect recombination in PanSV.

| Genebank accession # | Names/proposed namesa | Host | Sampling coordinates | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lon | Lat | |||

| Y00514 | MSV-A [ZA-SA-1986] | Maize | 26.82875 | -26.7688 |

| EU628597 | MSV-B [ZA-PlaB-g27-2006] | Unidentified | 19.92809 | -33.6634 |

| AF007881 | MSV-C [ZA-Set-1998] | Setaria sp | 31.03495 | -29.697 |

| AF329889 | MSV-D [ZA-Raw-1998] | Unidentified | 19.74933 | -33.7435 |

| EU628626 | MSV-E [ZA-MitA-g125-2006] | Digitaria ciliaris | 31.00939 | -29.8259 |

| EU628629 | MSV-F [NG-IntB-g88-2007] | Urochloa maxima | 3.898865 | 7.406774 |

| EU628631 | MSV-G [TD-Mic24-1987] | Digitaria sp. | -7.8882 | 12.18787 |

| EU628638 | MSV-H [NG-Lag-g74-2007] | Setaria barbata | 4.666667 | 8.916667 |

| EU628639 | MSV-I [ZA-NewA-g217-2007] | Digitaria ciliaris | 30.89359 | -29.8126 |

| EU628641 | MSV-J [ZW-Mic24-1987] | Pennisetum sp. | 30.96333 | -17.8761 |

| EU628643 | MSV-K [UG-BusD-2005] | Eustachys petraea | 30.40586 | 0.458333 |

| GQ415390 | PanSV-E [KE-Nye5-g359-2008] | Panicum maximum | 36.95382 | -0.42397 |

| GQ415393 | PanSV-G [YT-Tsa-g386-2008] | Panicum maximum | 12.83897 | -45.1682 |

| GQ415394 | PanSV-G [YT-Com-g383-2008] | Panicum maximum | 12.7824 | -45.1298 |

| GQ415395 | PanSV-G [YT-Coc-g385-2008] | Panicum maximum | 12.8343 | -45.1399 |

| GQ415396 | PanSV-G [YT-Ben-g384-2008] | Panicum maximum | 12.84907 | -45.1907 |

| GQ415392 | PanSV-F [KE-Nye2-g364-2008] | Panicum maximum | 36.94854 | -0.41814 |

| GQ415389 | PanSV-E [KE-Nye4-g363-2008] | Panicum maximum | 36.94688 | -0.4004 |

| GQ415399 | PanSV-I [KE-Nra1-g374-2008] | Brachiaria Deflexa | 37.04521 | 0.18032 |

| GQ415399 | PanSV-I [KE-Nra2-g375-2008] | Brachiaria Deflexa | 37.04521 | 0.18032 |

| GQ415391 | PanSV-E [KE-Jic10-PKPM-1997]b | Panicum maximum | - | - |

| GQ415401 | PanSV-I [KE-Jic13-PKPB-1997]c | Panicum tricholadum | - | - |

| GQ415397 | PanSV-H [CF-Bai2-Car11-2008] | Brachiaria Deflexa | 17.98736 | 3.848061 |

| GQ415388 | PanSV-D [NG-Ola-g242-2007] | Urochloa maxima | 3.863739 | 7.411194 |

| GQ415398 | PanSV-H [NG-Jic15-PNP-1997]d | Panicum maximum | - | - |

| GQ415386 | PanSV-A [ZA-Ill-g263-2008] | Ehrharta calycina | 30.83108 | -30.0653 |

| GQ415387 | PanSV-A [MZ-Nac1-2009] | Panicum maximum | - | - |

| EU224261 | PanSV-A [ZA-Bak-M34-2005] | Ehrharta calycina | 26.7522 | -25.2321 |

| EU224262 | PanSV-A [ZA-For-g191-2007] | Ehrharta calycina | 31.03868 | -29.8545 |

| EU224263 | PanSV-A [ZM-Nya-g180-2007] | Urochloa plantaginea | 32.8533 | -18.5541 |

| EU224264 | PanSV-C [ZM-NGur-g169-2006] | Urochloa plantaginea | 30.8402 | -17.5216 |

| EU224265 | PanSV-D [NG-Ifo-g91-2006] | Urochloa maxima | 5.776853 | 6.901831 |

| L396381 | PanSV-A [ZA-Kar-1994] | Panicum maximum | 31.18425 | -25.4951 |

| X60168 | PanSV-B [KE-Ken-1991] | Panicum maximum | - | - |

| EU244915 | ESV [ZM-Gur-g186-2007] | Eragrostis curvula | 31.1021 | -17.8101 |

| EU244913 | SSRV-A [RE-Bas-R9-2006] | Setaria barbata | 55.2715 | -21.032 |

| EU244916 | SSRV-B [ZM-Nya-g177-2006] | Paspalum conjugatum | 32.9715 | -18.3213 |

| AF072672 | SSRV-A [RE-Reu] | Sugarcane | - | - |

| M82918 | SSV-A [ZA-SN-1991] | Sugarcane | - | - |

| EU244914 | SSV-B [RE-Pie-R5-2006] | Cenchrus myosuroides | 55.4817 | -21.3143 |

| AF239159 | SSEV [EG-Naga] | Sugarcane | - | - |

| AF037752 | SSEV [EG-Giza] | Sugarcane | - | - |

| EU445697 | USV [NG-Ipe-g226-2007] | Urochloa deflexa | 4.45 | 7.51667 |

| EU445699 | USV [NG-Eji2-g248-2007] | Urochloa deflexa | 4.32097 | 7.19889 |

| EU445698 | USV [NG-Eji-g230-2007] | Urochloa deflexa | 4.32097 | 7.19889 |

| EU445696 | USV [NG-Ile-g240-2007] | Urochloa deflexa | 4.24097 | 7.61211 |

| EU445693 | USV [NG-Iwo-g75-2006] | Urochloa deflexa | 4.17803 | 7.62595 |

| EU445692 | USV [NG-Lag1-g74-2006] | Urochloa deflexa | 4.66667 | 8.91667 |

| EU445694 | USV [NG-Lag2-g78-2006] | Urochloa deflexa | 4.64886 | 8.92724 |

| EU445695 | USV [NG-Odo-g89-2006] | Urochloa deflexa | 4.13646 | 7.46381 |

aIsolates sampled in the present study are indicated in bold type

bIsolate formerly named in P(K)P-M Pinner et al., (1988)

cIsolate formerly named P(K)P-B in Pinner et al., (1988)

dIsolate formerly named P(N)P in Pinner et al., (1988)

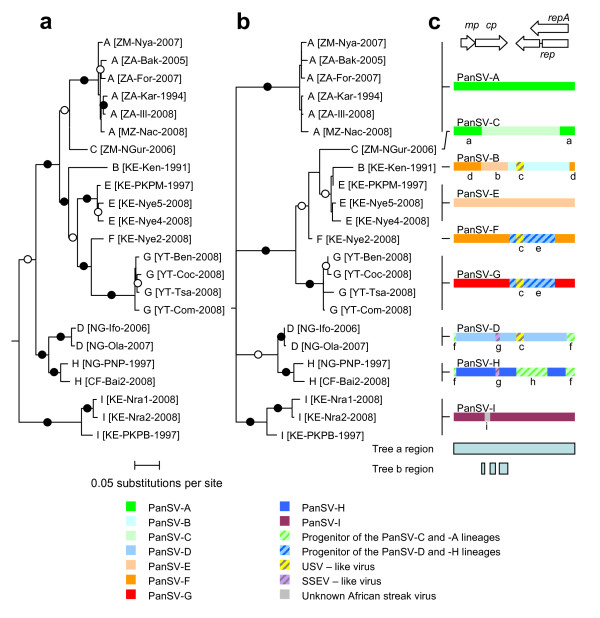

Figure 1.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees (both constructed with the GTR+G4 nucleotide substitution model) indicating possible evolutionary relationships between 23 PanSV isolates. (a) Tree constructed using complete genome sequences. Virus names take the form "Strain [country-region-year of isolation]" (b) A tree constructed using recombination-free portions of the genome indicated beneath the genome map and recombination mosaic cartoons in c. (c) Linearised genome cartoons depicting unique recombinant mosaics detected amongst the PanSV sequences. Colours represent as best as possible the origins of different genome regions. Letters below the depicted recombination events correspond to detailed descriptions of each of the events given in Additional file 7. For labels on the genome map: mp = movement protein gene, cp = coat protein gene, rep = replication associated protein gene, repA = RepA gene. Whereas branches marked with filled and open circles were supported in >90% and 70-89% of bootstrap replicates, respectively, branches with <50% bootstrap support have been collapsed. The tree was rooted on the Sugarcane streak Reunion virus isolate SSRV-Bas (not shown).

Although the newly described PanSV-I strain represented the most divergent group of PanSV isolates yet discovered, we found no major genomic features that could distinguish this or any of the other newly described PanSV strains from those already represented in public sequence databases (see additional files 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 for annotated genome and probable expressed protein maps).

Recombination between PanSV strains

It has been previously determined that recombination has featured prominently in the evolution of MSV strains [12] and that it may have also contributed substantially to the diversification of PanSV [11]. We therefore analysed the PanSV sequences for evidence of inter-species and inter-strain recombination events using a battery of recombination detection and analysis methods implemented in the program RDP3 [24]. We identified clear evidence of three inter-species (labeled a, b, d, e, f, and h in Figure 1 and Additional File 7) and six inter-strain recombination events (labeled a, b, d, e, f, and h in Figure 1) within the PanSV sequences.

The pattern of recombination we observed in PanSV is very similar to that which has been described for MSV [12]. For both species most detectable recombination events have involved intra-species sequence exchanges. The few inter-species recombination events that have been detected in both species have also all involved the exchange of small (<200 nt) tracts of sequence.

Another similarity between the two species is that many of the described strains have apparently arisen through inter-strain recombination events. For MSV all currently sampled isolates of seven of the eleven described strains (MSV-A, -F, -H, -J, K, C and D) share evidence of ancestral inter-strain recombination events that involved exchanges of genome fragments >30% of the full genome [12]. Likewise, exchanges of >30% genome size fragments are evident in all sampled representatives of five of the nine PanSV strains (PanSV-B, -C, -H, F and G).

The patterns of recombination seen in PanSV and MSV, where inter-species recombination events generally involve exchanges of only small genomic fragments (<10% of the full genome length), is quite different to that seen amongst related whitefly transmitted geminiviruses in the genus Begomovirus [15,16]. In these viruses inter-species recombination is very common and often involves exchanges of large (>30% of the full genome length) genome fragments. This difference is due, at least in part, to differences between the species classification criteria used for mastreviruses and begomoviruses. Whereas the main begomovirus species demarcation criterion is that DNA-A or DNA-A-like sequences (begomoviruses often have two component genomes where the DNA-A component of such genomes is largely homologous to mastrevirus genomes) sharing <89% identity belong to different species, the analogous mastrevirus species demarcation threshold is 75%. If the begomovirus classification scheme were applied to PanSV and MSV then, many of the inter-strain recombination events detectable in these species would be "upgraded" to inter-species recombination events.

It is still noteworthy, however, that detectable recombination events between more distantly related PanSV and MSV genomes have been less frequent and have tended to involve smaller sequence exchanges than recombination events between more closely related genomes. It is possible that the observed ratios of intra:inter species recombination events in PanSV and MSV might be partially attributable to mixed infections involving different mastrevirus species being rarer than mixed infections involving different strains of the same species. Although many of the different African streak virus species share hosts such as Urochloa and Eragrostis species, there are probably greater host-range differences between viruses in different species than there are between viruses within the same species. Such differences should surely influence the relative frequencies of mixed species and mixed strain infections and should therefore also influence the relative rates of inter-species and intra-species recombination events.

The most striking difference between the inter- and intra-species recombination events in these viruses is, however, not their relative frequencies, but rather the relative amounts of sequence that have been exchanged in these different recombination event categories. This pattern of recombination in fact conforms very well with the hypothesis that a major determinant of recombinant fitness is how well foreign DNA fragments function within the context of genomic backgrounds that they did not co-evolve within [25-29]. Functional nucleotide sequences tend to work best within genomes that are similar to the ones in which they evolved [25,27,30]. The probable reason for this is simply that the interaction networks that define the functionality of a particular nucleotide sequence within any given genomic context could potentially be disrupted if that sequence were placed into a genome where it was forced to interact with nucleotide sequences different from those it co-evolved with. As the relatedness between prospective parental sequences drops so too should the proportion of their genomes that could be exchanged without disrupting the delicate intra-genomic interactions required for optimal fitness [27,31]. The net effect of this process should be that amongst (presumably high fitness) genomes sampled from nature, one should tend to observe larger sequence exchanges between more closely related genomes than are detectable between less closely related ones. This is the exact pattern of recombination seen in both PanSV and MSV, suggesting that rather than inter-species recombination events being uncommon due entirely to different mastrevirus species only rarely infecting the same hosts, they are uncommon because of genetic constraints on the relative viability of inter-species recombinants.

PanSV and MSV phylogenies display similar patterns of geographical structure

It has been previously demonstrated that there are strong signals of geographical structure within the phylogenetic trees of both the maize adapted MSV strain, MSV-A [14,22], and the grass adapted MSV strain, MSV-B [12]. These two strains differ, however, in the degree to which viruses have been moving across Africa [12]. Whereas no MSV-B isolates have ever been detected in West Africa, there have apparently been no movements of MSV-B isolates between East Africa, southern Africa and the Indian Ocean island of La Reunion since the initial spread of this strain to these three locations. Conversely, in the time since MSV-A first spread throughout the continent there have apparently been multiple instances where these viruses have moved between the major regions of Africa [12,22].

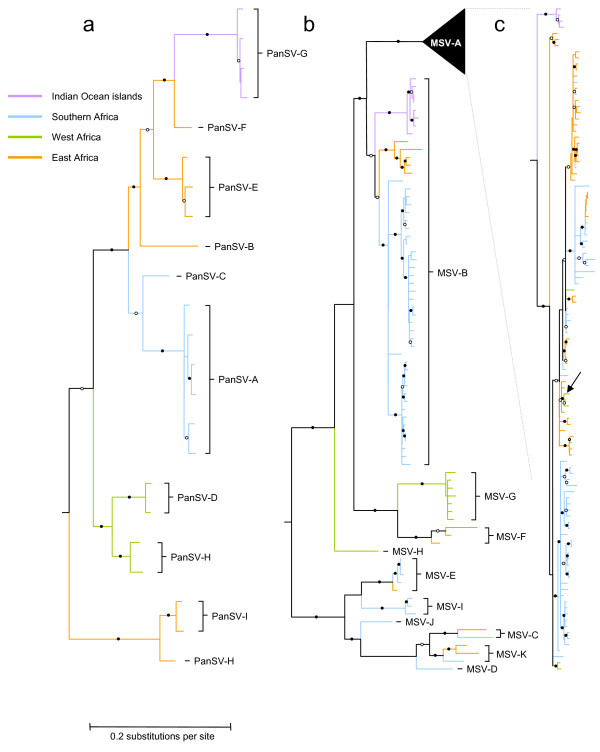

We sought to determine whether similar phylogeographic patterns exist amongst the currently sampled PanSV sequences. Taking note of the locations from which sequences were sampled, we compared the PanSV and MSV phylogenies (Figure 2) and noted some striking similarities between them with respect to the geographical ranges of the various distinct strain groupings represented.

Figure 2.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees (best fit nucleotide substitution models = GTR+G4 for PanSV tree and GTR+I+G4 for the MSV tree) depicting the sampling locations of 23 PanSV (tree a) and 181 MSV isolates (trees b and c). Branches are colored according to sampling locations (blue = southern African lineages, orange = East African lineages, green = West African lineages, purple = Indian Ocean island lineages). Wherever under a maximum parsimony criterion, it is <60% certain that ancestral sequences represented by tree nodes are from one of the four regions, the branches basal to that node have been left uncoloured. Whereas branches marked with filled and open circles were supported in >90% and 70-89% of bootstrap replicates, respectively, branches with <50% bootstrap support have been collapsed. The arrow on tree c indicates a clade of MSV-A sequences from West Africa nested within a clade of MSV-A sequences from East Africa indicating an instance of recent east to west movement of MSV-A isolates. All the trees were rooted on the Sugarcane streak Reunion virus isolate SSRV-Bas (not shown).

Besides both MSV and PanSV strains clearly grouping according to their sampling locations, it is evident that PanSV (Figure 2a) and grass adapted MSV strains (Figure 2b) from East Africa, Southern Africa and the Indian Ocean islands are generally more closely related to one another than they are to viruses from West Africa. Taken together with the MSV data, the PanSV sample therefore provides additional evidence that, in general, African streak viruses may move more freely between East Africa, southern Africa and the Indian Ocean islands than they do between these regions and West Africa [12]. This pattern is notably different from that seen for both the maize adapted MSV-A strain and whitefly transmitted geminiviruses in the genus Begomovirus. Whereas island begomovirus populations display strong evidence of extensive isolation from mainland lineages [32,33], there is good phylogeographic evidence, particularly for cassava infecting begomoviruses, of lineages moving between the major regions of the continent [34]. Cassava infecting begomoviruses might, however, represent a special case in that cassava is propagated from cuttings and its viruses might therefore be moved more extensively by humans than viruses infecting seed propagated hosts.

Unlike with the wild-grass infecting MSV and PanSV strains, the maize adapted MSV-A strain (Figure 2c) has apparently moved quite extensively throughout the continent with the Indian Ocean islands being relatively more isolated than West Africa [12,35]. There is in fact clear evidence of at least one fairly recent movement of a MSV-A lineage from East Africa to West Africa (see arrow indicating the green clade nested within the orange clade in Figure 2c). Similar east to west movements across Africa have been detected in various other vector-born plant viruses including whitefly transmitted cassava infecting geminivirus species [34,36] and the beetle transmitted sobemovirus species, Rice yellow mottle virus [37,38]. It remains to be determined, however, whether movement of MSV-A and perhaps these other viruses too is natural or whether it is facilitated by human trafficking of infected plant material/viruliferous vectors [12,39]. It is also currently unknown whether PanSV, the grass adapted MSV strains and MSV-A are adapted to transmission by either different Cicadulina species or different biotypes within these species. MSV-A is transmitted with varying efficiencies by different Cicadulina species [40], and it remains a strong possibility that differences in the geographical distribution and migration routes of different preferred vector species might also account for differences in the movement patterns of these virus groups across East and West Africa.

The final subtle difference between the grass adapted MSV-strains and the PanSV dataset are the genetic distances between viruses found in different regions. Since the same demarcation threshold was used in both the MSV and PanSV strain classifications it is perhaps interesting that in no case was any PanSV strain detected in more than one of the surveyed regions. Members of each of the MSV-B -C, -E,-F and -K strains have been isolated across multiple geographical regions (three for MSV-B and two each for the rest). Assuming that the PanSV and grass adapted MSV strains are evolving at approximately the same rate, this observation indicates that over the time-scales represented by these phylogenies, MSV moves more frequently than PanSV between the regions examined. Without comparative analysis of PanSV and MSV substitution rates, however, it cannot be discounted that, rather than moving at different rates, the two species are simply evolving at different rates. It is also possible that with better sampling the isolates of different PanSV strains will, as is the case for MSV, be found in multiple different regions of Africa.

With these reservations noted, it is nevertheless interesting that just as MSV-A seems to be moving across Africa with less restraint than grass adapted MSV strains, the grass adapted MSV strains are in turn apparently moving more freely across the continent than PanSV strains. It is therefore possible that the evolution of epidemiological traits enabling MSV to move more rapidly than PanSV across Africa was important for the eventual evolution of still faster rates of MSV-A movement.

Conclusion

Among 16 new PanSV isolates sampled across Africa and the Indian Ocean island of Mayotte we have potentially discovered five new PanSV strains. Together with other currently sampled PanSV genome sequences these new PanSV isolates indicate that there exist striking similarities between PanSV and MSV with respect to both detectable recombination patterns and degrees of geography-associated population structure. Although similarities between PanSV and MSV are perhaps unsurprising considering that these viruses share common leafhopper vector species and partially overlapping host-ranges, it remains interesting that both MSV strains in general, and the MSV-A strain in particular, seem to be less constrained in their movements across Africa than PanSV strains.

Methods

Virus Isolates

Sixteen grasses presenting with mild streak symptoms characteristic of African streak virus infections were sampled from various locations in Africa and the Indian ocean island of Mayotte: one Brachiaria deflexa sample from Central African Republic; four Panicum maximum samples from Mayotte; one Urochloa maxima and one Panicum maximum sample from Nigeria; four Panicum maximum, two Brachiaria deflexa and one Panicum trichocladium samples from Kenya; one Ehrharta calycina sample from South Africa and one Panicum maximum sample from Mozambique (locations and names are provided in Table 1). The Nigerian isolate, PanSV-H [NG-Jic15-PNP-1997], and the Kenyan isolates, PanSV-E [KE-Jic10-PKPM-1997] and PanSV-I [KE-Jic13-PKPB-1997] (respectively referred to as P(N)P, P(K)P-M and P(K)P-B in [5,41]), were sampled in ~1987 but were maintained for approximately ten years within Panicum maximum under glasshouse conditions at the John Innes Centre in Norwich prior to leaf tissues being harvested and frozen. Full length PanSV genomes were amplified from leaf tissues using rolling circle amplification, cloned and sequenced using methods described previously [42-44]. Briefly, total DNA was either extracted from leaf tissues using Extract-n-Amp™ Plant PCR Kit (Sigma-Aldrich Corporation, USA) or using a Qiagen Plant miniprep DNA kit (Qiagen, Germany) and circular DNA molecules were amplified using φ 29 DNA polymerase (TempliPhi™, GE Healthcare). The amplified concatamers were digested with BamHI, SalI or XhoI restriction enzymes to release ~2.7 kb PanSV genomes which were subsequently ligated to similarly linearised pGEM3 Zf(+) (from Promega Biotech). The cloned PanSV genomes were sequenced by Macrogen Inc (Korea) using primer walking. Sequences were assembled and edited using DNAMAN (version 5.2.9; Lynnon Biosoft) and MEGA (version 4)[45].

Diversity Analysis

34 African streak virus full genome sequences, including all those available in GenBank for PanSV [3,11], and representative selections of MSV [12], USV [10], ESV [8], Sugarcane streak virus [4,8], Sugarcane streak Egypt virus [2], and Sugarcane streak Reunion virus [2,8], were obtained from GenBank. These were aligned together with the 16 new PanSV sequences using POA (vesion 2) [46] and edited by eye using MEGA. For purposes of assigning PanSV sequences to different strain groupings using the 93% rule of Martin et al [14], MEGA was also used to calculate the pair-wise differences between aligned PanSV genomes using p-distances with pair-wise deletion of gaps (as opposed to scoring gaps as a fifth nucleotide state). Alignments used in earlier phylogeographic analyses described in [12] and [22] were merged (with duplicate sequences being discarded) and realigned with MEGA.

Recombination and phylogenetic analysis

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees were constructed using PHYML (version 1)[47] with automated best-fit model selection under the Akaike information criterion as described in [48].

Discreet recombination events were detected using the RDP [49], GENECONV [16], BOOTSCAN [50], MAXCHI [51], CHIMAERA [52], SISCAN [53], and 3SEQ [54] methods implemented in the program RDP3 (version 3.32; available from http://darwin.uvigo.es/rdp/rdp.html)[24]. Only potential recombination signals detected by at least three of the seven applied recombination detection methods, coupled with phylogenetic evidence of recombination were considered significant evidence of the signals representing genuine recombination events. Parental and recombinant sequences were identified from the sets of sequences used to detect recombination events as outlined in [55] and [56]. Recombination breakpoint positions and recombinant/parental designations were manually checked and adjusted where necessary using the extensive phylogenetic and recombination signal analysis features implemented in RDP3.

Abbreviations

ESV: Eragrostis streak virus; cp: coat protein gene; LIR: long intergenic region; mp: movement protein gene; MSV: Maize streak virus; PanSV: Panicum streak virus; rep: replication associate protein gene; repA: RepA gene; SIR: short intergenic region; SSEV: Sugarcane streak Egypt virus; SSRV: Sugarcane streak Reunion virus; SSV: Sugarcane streak virus; USV: Urochloa streak virus.sacSV.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

AV, DPM, ALM, JML, SO, JZ, EKK, DPL, NM. JM, SS PGM and RWB collected isolates. AV, ALM, and LD cloned and sequenced the viruses. AV, PL and DPM conceived the project, AV and DPM analysed the data. AV and DPM prepared the manuscript and AV, PL, JML and DPM secured funding for the project's execution. EPR, PL and RWB provided ideas and comments during manuscript preparation. All authors other than PGM read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Graph rationalizing the use with PanSV of the same 93% sequence identity strain demarcation threshold used for MSV. Graph rationalizing the use with PanSV of the same 93% sequence identity strain demarcation threshold used for MSV. The red and blue splines respectively plots the frequencies of pairwise sequence identities shared amongst 23 PanSV (253 pairwise distances) and 99 MSV isolates (corresponding to the MSV dataset used in Varsani et al [2008] and accounting for 4851 pairwise distances) at a resolution of 1% identity. Identity values were calculated with pairwise exclusion of alignment gaps (as opposed to counting gaps as a fifth state as is often currently done, either by accident or design, by many geminivirologists).

Full genome sequence alignments of 23 PanSV isolates. Annotated full genome sequence alignments of 23 PanSV isolates. Sequences either known or believed to have some role in mastrevirus replication and transcription are marked together with a corresponding label on the nucleotide sequence alignments. To highlight differences between the sequences, wherever nucleotides in a particular alignment column are identical to that of PanSV-A [ZM-Nya-g180-2007] they are replaced with a "-" character. In columns where they differ from PanSV-A [ZM-Nya-g180-2007] they are shown in lower case. "." characters indicate where gaps were inserted to align the sequences. [1] Stenger, et al., 1991. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:8029; [2] Sunter, et al. 1985. Nucl. Acids Res. 13:4645; [3] Argüello-Astorga et al. 1994. Virology 203:90; [4] Suárez-López et al. 1995. Virology. 208:303; [5] Morris-Krsinich et al. 1984. Nucleic Acids Res. 13:7237; [6] Boulton et al. 1989. J. Gen. Virol. 70:2309; [7] Wright et al.1997 Plant J. 12:1285; [8] Donson et al. 1984. EMBO J. 3:3069; [9] Dekker et al.1991. Nucl. Acids Res. 19:4075; [10] Fenoll et al. 1990. Plant. Mol. Biol. 15:865.

Annotated predicted movement protein amino acid sequence alignments. Annotated predicted movement protein amino acid sequence alignments of 23 PanSV isolates. The hydrophobic, potentially membrane spanning internal domain of the sequences is highlighted. [1] Wright et al.1997. Plant J. 12:1285.

Annotated predicted coat protein amino acid sequence alignments. Annotated predicted coat protein amino acid sequence alignments of 23 PanSV isolates. The potential nuclear localization signal and DNA binding domains (inferred by analogy with those determined for MSV) are highlighted on the sequence. [1] Liu et al. 1999. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 12:894; [2] Liu et al. 1997. J. Gen. Virol. 78:1265.

Annotated predicted replication-associated protein amino acid sequence alignments. Annotated predicted replication-associated protein amino acid sequence alignments of 23 PanSV isolates. Potential rolling-circle replication motifs and interaction domains inferred by analogy with MSV and Wheat dwarf virus are highlighted. [1] Koonin & Ilyina. 1992. J Gen Virol, 73:2763; [2] Horvath et al. 1998. Plant Mol. Biol. 38:699; [3] Xie et al. 1995. EMBO J. 14:4073; [4] Gorbalenya & Koonin. 1989. Nucl. Acids Res. 17:8413.

Annotated predicted RepA amino acid sequence alignments. Annotated predicted RepA amino acid sequence alignments of 23 PanSV isolates. Potential rolling circle replication motifs and interaction domains inferred by analogy with MSV and Wheat dwarf virus are highlighted. [1] Koonin & Ilyina. 1992. J Gen Virol, 73:2763; [2] Horvath et al. 1998. Plant Mol. Biol. 38:699; [3] Xie et al. 1995. EMBO J. 14:4073; [4] Xie et al. 1999. Plant Mol. Biol. 39:647.

Recombination in PanSV. Details of the PanSV recombination events detected in this study including approximate breakpoint positions, parental-like sequences, and p-values for various recombination detection tests.

Contributor Information

Arvind Varsani, Email: arvind.varsani@canterbury.ac.nz.

Aderito L Monjane, Email: aderito.monjane@uct.ac.za.

Lara Donaldson, Email: lara.donaldson@uct.ac.za.

Sunday Oluwafemi, Email: soluwafemi2000@yahoo.com.

Innocent Zinga, Email: innocentzinga@yahoo.fr.

Ephrem K Komba, Email: koshkomba2002@yahoo.fr.

Didier Plakoutene, Email: hosanalak2@yahoo.fr.

Noella Mandakombo, Email: mandqkombonoella@yahoo.fr.

Joseph Mboukoulida, Email: mboukoulida_joseph@yahoo.fr.

Silla Semballa, Email: semballa.silla1@yahoo.fr.

Rob W Briddon, Email: rob.briddon@gmail.com.

Peter G Markham, Email: markham@beckcottages.orangehome.co.uk.

Jean-Michel Lett, Email: jean-michel.lett@cirad.fr.

Pierre Lefeuvre, Email: pierre.lefeuvre@cirad.fr.

Edward P Rybicki, Email: ed.rybicki@uct.ac.za.

Darren P Martin, Email: darrin.Martin@uct.ac.za.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the South African National Research Foundation. AV was supported by the Carnegie Corporation of New York. DPM was supported by the Wellcome Trust. PL and JML were supported by the Conseil Régional de La Réunion, CIRAD, European Union (FEDER) and GIS Centre de recherche et de veille sanitaire sur les maladies émergentes dans l'océan Indien (N°PRAO/AIRD/CRVOI/08/03). RWB is supported by the Higher Education Commission, Government of Pakistan, under the "Foreign Faculty Hiring Program".

References

- Shepherd DN, Martin DP, Walt E van der, Dent K, Varsani A, Rybicki EP. Maize streak virus: an old and complex 'emerging' pathogen. Mol Plant Path. 2009. in press . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bigarré L, Salah M, Granier M, Frutos R, Thouvenel JC, Peterschmitt M. Nucleotide sequence evidence for three distinct sugarcane streak mastreviruses. Arch Virol. 1999;6:2331–2344. doi: 10.1007/s007050050647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briddon RW, Lunness P, Chamberlin LC, Pinner MS, Brundish H, Markham PG. The nucleotide sequence of an infectious insect-transmissible clone of the geminivirus Panicum streak virus. J Gen Virol. 1992;6:1041–1047. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-5-1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes FL, Rybicki EP, Kirby R. Complete nucleotide sequence of sugarcane streak Monogeminivirus. Arch Virol. 1993;6:171–182. doi: 10.1007/BF01309851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinner MS, Markham PG, Markham RH, Dekker EL. Characterization of maize streak virus:description of strains; symptoms. Plant Path. 1988;6:74–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.1988.tb02198.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peterschmitt M, Reynaud B, Sommermeyer G, Baudin P. Characterization of maize streak virus isolates using monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies and by transmission to a few hosts. Plant Dis. 1991;6:27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Storey HH, McClean APD. The transmission of streak disease between maize, sugarcane and wild grasses. Ann Appl Biol. 1930;6:691–719. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1930.tb07240.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd DN, Varsani A, Windram O, Lefeuvre P, Monjane AL, Owor B, Martin DP. Novel Sugarcane streak virus and Sugarcane streak Reunion virus mastrevirus isolates from Southern Africa and La Reunion. Arch Virol. 2008;6:605–609. doi: 10.1007/s00705-007-0016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawry R, Martin DP, Shepherd DN, van Antwerpen T, Varsani A. A novel sugarcane-infecting mastrevirus species from South Africa. Arch Virol. 2009;6:1699–1703. doi: 10.1007/s00705-009-0490-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oluwafemi S, Varsani A, Monjane AL, Shepherd DN, Owor BE, Rybicki EP, Martin DP. A new African streak virus species from Nigeria. Arch Virol. 2008;6:1407–1410. doi: 10.1007/s00705-008-0123-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varsani A, Oluwafemi S, Shepherd DN, Monjane AL, Owor B, Windram O, Rybicki EP, Lefeuvre P, Martin DP. Panicum streak virus diversity is similar to that observed for Maize streak virus. Arch Virol. 2008;6:601–604. doi: 10.1007/s00705-007-0020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varsani A, Shepherd DN, Monjane AL, Owor BE, Erdmann JB, Rybicki EP, Peterschmitt M, Briddon RW, Markham PG, Oluwafemi S, Windram OP, Lefeuvre P, Lett JM, Martin DP. Recombination, decreased host specificity and increased mobility may have driven the emergence of maize streak virus as an agricultural pathogen. J Gen Virol. 2008;6:2063–2074. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/003590-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnippenkoetter WH, Martin DP, Hughes F, Fyvie M, Willment JA, James D, von Wechmar B, Rybicki EP. The biological and genomic characterisation of three mastreviruses. Arch Virol. 2001;6:1075–1088. doi: 10.1007/s007050170107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DP, Willment JA, Billharz R, Velders R, Odhiambo B, Njuguna J, James D, Rybicki EP. Sequence diversity and virulence in Zea mays of Maize streak virus isolates. Virology. 2001;6:247–255. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefeuvre P, Lett JM, Varsani A, Martin DP. Widely conserved recombination patterns among single-stranded DNA viruses. J Virol. 2009;6:2697–2707. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02152-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padidam M, Sawyer S, Fauquet CM. Possible emergence of new geminiviruses by frequent recombination. Virology. 1999;6:218–225. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fondong VN, Pita JS, Rey ME, de Kochko A, Beachy RN, Fauquet CM. Evidence of synergism between African cassava mosaic virus and a new double-recombinant geminivirus infecting cassava in Cameroon. J Gen Virol. 2000;6:287–297. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-1-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pita JS, Fondong VN, Sangaré A, Otim-Nape GW, Ogwal S, Fauquet CM. Recombination, pseudorecombination and synergism of geminiviruses are determinant keys to the epidemic of severe cassava mosaic disease in Uganda. J Gen Virol. 2001;6:655–665. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-3-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monci F, Sánchez-Campos S, Navas-Castillo J, Moriones E. A natural recombinant between the geminiviruses Tomato yellow leaf curl Sardinia virus and Tomato yellow leaf curl virus exhibits a novel pathogenic phenotype and is becoming prevalent in Spanish populations. Virology. 2002;6:317–326. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Andrés S, Tomas DM, Sanchez-Campos S, Navas-Castillo J, Moriones E. Frequent occurrence of recombinants in mixed infections of tomato yellow leaf curl disease-associated begomoviruses. Virology. 2007;6:210–219. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Andrés S, Accotto GP, Navas-Castillo J, Moriones E. Founder effect, plant host, and recombination shape the emergent population of begomoviruses that cause the tomato yellow leaf curl disease in the Mediterranean basin. Virology. 2007;6:302–312. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkins GW, Martin DP, Duffy S, Monjane AL, Shepherd DN, Windram OP, Owor BE, Donaldson L, van Antwerpen T, Sayed RA, Flett B, Ramusi M, Rybicki EP, Peterschmitt M, Varsani A. Dating the origins of the maize-adapted strain of maize streak virus, MSV-A. J Gen Virol. 2009;6:3066–3074. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.015537-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley J, Bisaro DM, Briddon RW, Brown JK, Fauquet CM, Harrison BD, Rybicki EP, Stenger DC. In: Geminiviridae. Fauquet CM, Mayo MA, Maniloff J, Desselberger U, Ball LA, editor. Virus Taxonomy (VIIIth Report of the ICTV). Elsevier/Academic Press, London; 2005. pp. 301–306. [Google Scholar]

- Martin DP, Williamson C, Posada D. RDP2: recombination detection and analysis from sequence alignments. Bioinformatics. 2005;6:260–262. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escriu F, Fraile A, García-Arenal F. Constraints to genetic exchange support gene coadaptation in a tripartite RNA virus. PLoS Pathog. 2007;6:e8. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefeuvre P, Lett JM, Reynaud B, Martin DP. Avoidance of protein fold disruption in natural virus recombinants. PLoS Pathog. 2007;6:e181. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DP, Walt E van der, Posada D, Rybicki EP. The evolutionary value of recombination is constrained by genome modularity. PLoS Genet. 2005;6:e51. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno IM, Malpica JM, Diaz-Pendon JA, Moriones E, Fraile A, García-Arenal F. Variability and genetic structure of the population of watermelon mosaic virus infecting melon in Spain. Virology. 2004;6:451–460. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DP, Rybicki EP. Investigation of Maize streak virus pathogenicity determinants using chimaeric genomes. Virology. 2002;6:180–188. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walt E van der, Palmer K, Martin DP, Rybicki EP. Viable chimaeric viruses confirm the biological importance of sequence specific maize streak virus movement protein and coat protein interactions. Virol J. 2008;6:61. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-5-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer MM, Silberg JJ, Voigt CA, Endelman JB, Mayo SL, Wang ZG, Arnold FH. Library analysis of SCHEMA-guided protein recombination. Protein Sci. 2003;6:1686–1693. doi: 10.1110/ps.0306603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefeuvre P, Martin DP, Hoareau M, Naze F, Delatte H, Thierry M, Varsani A, Becker N, Reynaud B, Lett JM. Begomovirus 'melting pot' in the south-west Indian Ocean islands: molecular diversity and evolution through recombination. J Gen Virol. 2007;6:3458–3468. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83252-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delatte H, Martin DP, Naze F, Goldbach R, Reynaud B, Peterschmitt M, Lett JM. South West Indian Ocean islands tomato begomovirus populations represent a new major monopartite begomovirus group. J Gen Virol. 2005;6:1533–1542. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80805-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndunguru J, Legg JP, Aveling TA, Thompson G, Fauquet CM. Molecular biodiversity of cassava begomoviruses in Tanzania: evolution of cassava geminiviruses in Africa and evidence for East Africa being a center of diversity of cassava geminiviruses. Virol J. 2005;6:21. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-2-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterschmitt M, Granier M, Frutos R, Reynaud B. Infectivity and complete nucleotide sequence of the genome of a genetically distinct strain of maize streak virus from Réunion Island. Arch Virol. 1996;6:1637–1650. doi: 10.1007/BF01718288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legg JP, Fauquet CM. Cassava mosaic geminiviruses in Africa. Plant Mol Biol. 2004;6:585–599. doi: 10.1007/s11103-004-1651-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traoré O, Pinel-Galzi A, Sorho F, Sarra S, Rakotomalala M, Sangu E, Kanyeka Z, Séré Y, Konaté G, Fargette D. A reassessment of the epidemiology of Rice yellow mottle virus following recent advances in field and molecular studies. Virus Res. 2009;6:258–267. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traore O, Sorho F, Pinel A, Abubakar Z, Banwo O, Maley J, Hebrard E, Winter S, Sere Y, Konate G, Fargette D. Processes of diversification and dispersion of rice yellow mottle virus inferred from large-scale and high-resolution phylogeographical studies. Mol Ecol. 2005;6:2097–2110. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fargette D, Konaté G, Fauquet C, Muller E, Peterschmitt M, Thresh JM. Molecular ecology and emergence of tropical plant viruses. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2006;6:235–260. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.44.120705.104644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oluwafemi S, Jackai LE, Alegbejo MD. Comparison of transmission abilities of four Cicadulina species vectors of maize streak virus from Nigeria. Ent Exp Et App. 2007;6:235–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1570-7458.2007.00577.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pinner MS, Markham PG. Serotyping and strain identification of maize streak virus isolates. J Gen Virol. 1990;6:1635–1640. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-8-1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue-Nagata AK, Albuquerque LC, Rocha WB, Nagata T. A simple method for cloning the complete begomovirus genome using the bacteriophage phi29 DNA polymerase. J Virol Methods. 2004;6:209–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2003.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owor BE, Shepherd DN, Taylor NJ, Edema R, Monjane AL, Thomson JA, Martin DP, Varsani A. Successful application of FTA Classic Card technology and use of bacteriophage phi29 DNA polymerase for large-scale field sampling and cloning of complete maize streak virus genomes. J Virol Methods. 2007;6:100–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd DN, Martin DP, Lefeuvre P, Monjane AL, Owor BE, Rybicki EP, Varsani A. A protocol for the rapid isolation of full geminivirus genomes from dried plant tissue. J Virol Methods. 2008;6:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;6:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasso C, Lee C. Combining partial order alignment and progressive multiple sequence alignment increases alignment speed and scalability to very large alignment problems. Bioinformatics. 2004;6:1546–1556. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S, Gascuel O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol. 2003;6:696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada D. jModelTest: phylogenetic model averaging. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;6:1253–1256. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin D, Rybicki E. RDP: detection of recombination amongst aligned sequences. Bioinformatics. 2000;6:562–563. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.6.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DP, Posada D, Crandall KA, Williamson C. A modified bootscan algorithm for automated identification of recombinant sequences and recombination breakpoints. AIDS and Human Retroviruses. 2005;6:98–102. doi: 10.1089/aid.2005.21.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard Smith J. Analyzing the mosaic structure of genes. J Mol Evol. 1992;6:126–129. doi: 10.1007/BF00182389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada D, Crandall KA. The effect of recombination on the accuracy of phylogeny estimation. J Mol Evol. 2002;6:396–402. doi: 10.1007/s00239-001-0034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs MJ, Armstrong JS, Gibbs AJ. Sister-Scanning: a Monte Carlo procedure for assessing signals in recombinant sequences. Bioinformatics. 2000;6:573–582. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.7.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boni MF, Posada D, Feldman MW. An exact nonparametric method for inferring mosaic structure in sequence triplets. Genetics. 2007;6:1035–1047. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.068874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath L, Walt E van der, Varsani A, Martin DP. Recombination patterns in aphthoviruses mirror those found in other picornaviruses. J Virol. 2006;6:11827–11832. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01100-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemey P, Lott M, Martin DP, Moulton V. Identifying recombinants in human and primate immunodeficiency virus sequence alignments using quartet scanning. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;6:126. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Graph rationalizing the use with PanSV of the same 93% sequence identity strain demarcation threshold used for MSV. Graph rationalizing the use with PanSV of the same 93% sequence identity strain demarcation threshold used for MSV. The red and blue splines respectively plots the frequencies of pairwise sequence identities shared amongst 23 PanSV (253 pairwise distances) and 99 MSV isolates (corresponding to the MSV dataset used in Varsani et al [2008] and accounting for 4851 pairwise distances) at a resolution of 1% identity. Identity values were calculated with pairwise exclusion of alignment gaps (as opposed to counting gaps as a fifth state as is often currently done, either by accident or design, by many geminivirologists).

Full genome sequence alignments of 23 PanSV isolates. Annotated full genome sequence alignments of 23 PanSV isolates. Sequences either known or believed to have some role in mastrevirus replication and transcription are marked together with a corresponding label on the nucleotide sequence alignments. To highlight differences between the sequences, wherever nucleotides in a particular alignment column are identical to that of PanSV-A [ZM-Nya-g180-2007] they are replaced with a "-" character. In columns where they differ from PanSV-A [ZM-Nya-g180-2007] they are shown in lower case. "." characters indicate where gaps were inserted to align the sequences. [1] Stenger, et al., 1991. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:8029; [2] Sunter, et al. 1985. Nucl. Acids Res. 13:4645; [3] Argüello-Astorga et al. 1994. Virology 203:90; [4] Suárez-López et al. 1995. Virology. 208:303; [5] Morris-Krsinich et al. 1984. Nucleic Acids Res. 13:7237; [6] Boulton et al. 1989. J. Gen. Virol. 70:2309; [7] Wright et al.1997 Plant J. 12:1285; [8] Donson et al. 1984. EMBO J. 3:3069; [9] Dekker et al.1991. Nucl. Acids Res. 19:4075; [10] Fenoll et al. 1990. Plant. Mol. Biol. 15:865.

Annotated predicted movement protein amino acid sequence alignments. Annotated predicted movement protein amino acid sequence alignments of 23 PanSV isolates. The hydrophobic, potentially membrane spanning internal domain of the sequences is highlighted. [1] Wright et al.1997. Plant J. 12:1285.

Annotated predicted coat protein amino acid sequence alignments. Annotated predicted coat protein amino acid sequence alignments of 23 PanSV isolates. The potential nuclear localization signal and DNA binding domains (inferred by analogy with those determined for MSV) are highlighted on the sequence. [1] Liu et al. 1999. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 12:894; [2] Liu et al. 1997. J. Gen. Virol. 78:1265.

Annotated predicted replication-associated protein amino acid sequence alignments. Annotated predicted replication-associated protein amino acid sequence alignments of 23 PanSV isolates. Potential rolling-circle replication motifs and interaction domains inferred by analogy with MSV and Wheat dwarf virus are highlighted. [1] Koonin & Ilyina. 1992. J Gen Virol, 73:2763; [2] Horvath et al. 1998. Plant Mol. Biol. 38:699; [3] Xie et al. 1995. EMBO J. 14:4073; [4] Gorbalenya & Koonin. 1989. Nucl. Acids Res. 17:8413.

Annotated predicted RepA amino acid sequence alignments. Annotated predicted RepA amino acid sequence alignments of 23 PanSV isolates. Potential rolling circle replication motifs and interaction domains inferred by analogy with MSV and Wheat dwarf virus are highlighted. [1] Koonin & Ilyina. 1992. J Gen Virol, 73:2763; [2] Horvath et al. 1998. Plant Mol. Biol. 38:699; [3] Xie et al. 1995. EMBO J. 14:4073; [4] Xie et al. 1999. Plant Mol. Biol. 39:647.

Recombination in PanSV. Details of the PanSV recombination events detected in this study including approximate breakpoint positions, parental-like sequences, and p-values for various recombination detection tests.