Abstract

Glutathione transferases are a multigene family of proteins that catalyze the conjugation of toxic electrophiles and carcinogens to glutathione. Glutathione transferase Pi (GSTP) is commonly overexpressed in human tumors and there is emerging evidence that the enzyme has additional cellular functions in addition to its role in drug and carcinogen detoxification. To investigate the unique functions of this enzyme, we have crossed Gstp null mice with an initiated model of colon cancer, the ApcMin mouse. In contrast to the ApcMin/+ Gstp1/p2+/+ (Gstp-wt ApcMin) mice, which rarely develop colonic tumours, ApcMin/+Gstp1/p2−/− (Gstp-null ApcMin) mice had a 6-fold increase in colon adenoma incidence, and a 50-fold increase in colorectal adenoma multiplicity, relative to Gstp-wt ApcMin. This increase was associated with early tumor onset and decreased survival. Analysis of the biochemical changes in the colon tissue of Gstp-null ApcMin mice demonstrated a marked induction of many inflammatory genes, including IL-6, IL-4, IFN-γ, and inducible nitric oxide synthase. In support of the induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase, a profound induction of nitrotyrosine adducts was observed. Gstp therefore appears to play a role in controlling inflammatory responses in the colon, which would explain the change in tumor incidence observed. These data also suggest that individual variation in GSTP levels may be a factor in colon cancer susceptibility.

Keywords: cancer, colorectal, inflammation

Glutathione S-transferases play a key role in chemical detoxification by catalyzing the conjugation of reduced glutathione to reactive electrophiles (1). In a genetic approach to study GST functions, we have generated mice nulled at the glutathione transferase Pi (GSTP) Gstp gene locus (2). These mice develop normally, are fertile, and show no obvious abnormalities. Topical application of the tumor initiator 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene, followed by the promoting agent 12–0-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate, resulted in a significant increase in the number of papillomas in null animals (2). Similarly, increased adenoma formation in the lungs of Gstp-null mice relative to wild-type mice was also observed following dosing with benzo[a]pyrene, 3-methylcholanthene and urethane (3). In recent studies we have obtained evidence that this protein can also modulate toxicological or carcinogenic response in a manner distinct from its role in chemical detoxification (4). Further evidence of unique GSTP function is demonstrated by its ability to form protein-protein interactions and regulate the activities of several cellular proteins (JNK and TRAF2) independently of its catalytic function (5, 6). GSTP has also been shown to potentiate S-glutathionylation reactions following oxidative and nitrosative stress in vitro and in vivo (7).

To further evaluate the role of GSTP in disease processes, we have investigated whether GSTP can alter colon cancer susceptibility in the ApcMin mouse. Mutations in the Apc gene is a major initiating factor in the aetiology of colorectal cancer in humans (8, 9). The ApcMin/+ mouse model of gastrointestinal tumorigenesis carries an ethylnitrosourea-induced mis-sense mutation of the adenomatous polyposis coli (Apc) gene at codon 850, which results in truncation of the APC protein (10). As a consequence, mutant APC is no longer able to bind β-catenin and induce its proteosomal degradation (11). β-Catenin is consequently transported into the nucleus and drives the Wnt signaling cascade, resulting in adenoma development predominantly in the small intestine of mice (10). Here, we report a profoundly increased adenoma incidence and multiplicity in the distal colon of ApcMin mice on a Gstp-null background. Furthermore, we also report that the absence of GSTP in the murine colon results in an inflammatory tissue environment consistent with some of the risk factors associated with colon cancer in humans.

Results

Decreased Survival, and Increased Incidence and Multiplicity of Adenomas, in the Large Intestine of Gstp-Null ApcMin Mice.

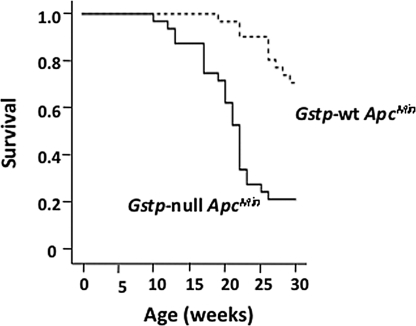

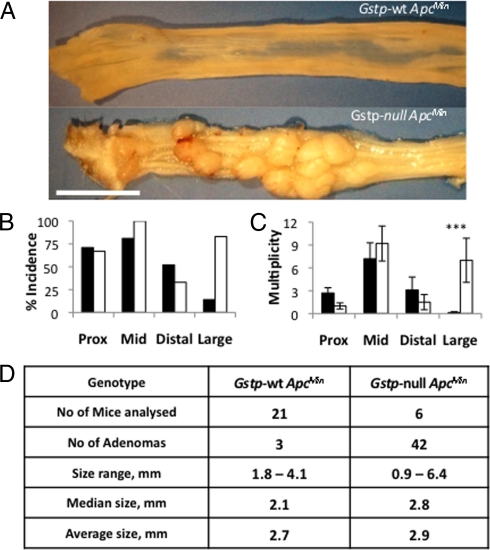

Gstp-null mice were crossed onto ApcMin mouse model of colorectal cancer to investigate the susceptibility of mice deficient in Gstp to colorectal adenomas. Early indications that ApcMin/+Gstp1/p2−/− (Gstp-null ApcMin) mice had an altered phenotype was seen in the greatly increased frequency of rectal prolapse and bleeding (63% vs. 17%). Gstp-null ApcMin mice also had significantly decreased survival, based on morbidity relative to Gstp-wt ApcMin (median 21.5 weeks vs. >30 weeks) (Fig. 1). The colons of Gstp-null ApcMin mice, killed as a result of ill-health, had a 3.5-fold increase in colorectal adenoma incidence (i.e., mice displaying at least a single adenoma; 71% vs. 20%, n = 30), and a 23-fold increase in colorectal adenoma multiplicity (average number of adenomas per mouse; 4.5 vs. 0.2, n = 30), relative to Gstp-wt ApcMin colons (Fig. 2A). Gstp-null ApcMin mice that survived to 30 weeks had a sixfold increase in adenoma incidence in the distal colon and a 17% increase in the mid-section of the small intestine (Fig. 2B). In contrast, in distal portions of the small intestine, a slight decrease (19%) in adenoma incidence was measured (Fig. 2B). Accompanying the increase in adenoma incidence, a 50-fold increase in adenoma multiplicity (average number of adenomas per mouse) occurred in the distal colon (Fig. 2C). Adenoma multiplicity did not differ significantly between genotypes for any segment of the small intestine investigated. The colonic adenomas in Gstp-null ApcMin and Gstp-wt ApcMin groups could not be distinguished on gross morphology (see Fig. 2 A and D). The loss of Gstp therefore profoundly increased the incidence and multiplicity of colonic adenomas in Gstp-null ApcMin mice.

Fig. 1.

Decreased survival of Gstp-null ApcMin mice. Kaplan-Meier survival curve showing Gstp-wt ApcMin (n = 30, 21 males and 9 females) and Gstp-null ApcMin mice (n = 32, 22 males and 10 females). These data are based on observed morbidity: that is, repeated rectal prolapse, rectal bleeding, blood in feces, within the terms of the Animal (Scientific Procedures) Act (1986).

Fig. 2.

Increased incidence and multiplicity of adenomas in the distal colon of Gstp-null ApcMin mice. (A) Gross pathology of polyps in the distal colon of Gstp-wt ApcMin and Gstp-null ApcMin mice. (Scale bar, 1 cm.) (B) Incidence (percentage of mice with one or more adenomas) and (C) multiplicity (number of adenomas per mouse) at week 30. (***, P < 0.0001, unpaired t test, n = 21 WT, 6 null). Data are mean ± SEM. Black bars are Gstp-wt ApcMin, white bars are Gstp-null ApcMin. (D) Table detailing adenoma size at 30 weeks. For further details, see Materials and Methods.

Adenoma Pathology.

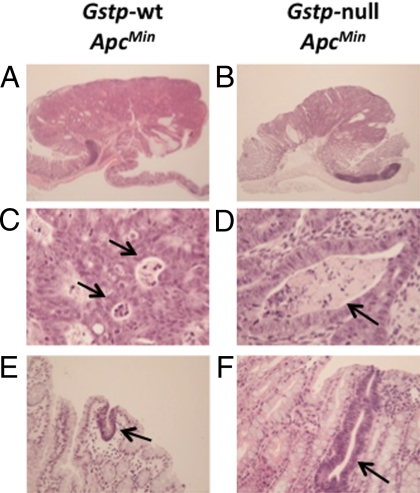

The histopathology of the tumors from each genotype was very similar. Tumors were predominantly tubular adenomas with a pedunculated morphology protruding into the colonic lumen (Fig. 3 A and B). There was no evidence of invasion of the underlying submucosa by neoplastic epithelial cells, and therefore none of the adenomas examined were classified as being carcinomas. Adenomas of both genotypes had high-grade dysplasia with foci of intraluminal necrosis (Fig. 3 C and D). The epithelial cells within the adenomas had a high nucleus:cytoplasm ratio and moderately prominent nucleoli. Unicryptal adenomas were also found in both genotypes and, again, did not differ in appearance (Fig. 3 E and F). In general, therefore, the adenomas found to arise in the distal colon of both Gstp-wt ApcMin and Gstp-null ApcMin mice were found to be microscopically very similar to high-grade colonic adenomas in humans.

Fig. 3.

Histology of colorectal adenomas. Gross histology of colorectal adenomas does not differ between (A) Gstp-wt ApcMin and (B) Gstp-null ApcMin genotypes. Magnification ×20. Advanced areas of necrosis (arrows) present in both (C) Gstp-wt ApcMin and (D) Gstp-null ApcMin. Magnification ×400. Examples of early adenomas (unicrypt, arrows) present in both (E) Gstp-wt ApcMin and (F) Gstp-null ApcMin mice. Magnification ×200. For further details, see Materials and Methods.

Molecular Analysis of Tumors.

In addition to mutations in the Apc gene, human colorectal cancer has been associated with mutations in genes such as K-ras and p53 (8), although the mutations are not always found mutated together in the same tumor (9). In our study we analyzed mutations at codons 12 and 13 of the K-ras gene and exons 5, 6, and 8 of the p53 gene (n = 19 for Gstp-null ApcMin mouse and n = 5 from Gstp-wt ApcMin mice). No mutations in the K-ras or Trp-53 genes were found.

Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of the normal Apc allele is an initiating event in the development of intestinal tumorigenesis in humans and is most commonly caused as a result of mitotic recombination (12, 13). We investigated the frequency of Apc LOH in both Gstp-wt ApcMin and Gstp-null ApcMin mice and found that LOH had occurred in all of the Gstp-wt ApcMin adenomas (4 out of 4) and 94% (17 out of 18) of Gstp-null ApcMin adenomas [supporting information (SI) Fig. S1]. These data demonstrate that LOH is a key event in adenoma formation in the Gstp-null ApcMin mouse line.

Studies into the Mechanism of the GSTP Effects.

GSTP could influence colon carcinogenesis by a number of different mechanisms. We therefore carried out a series of experiments to gain further insights into the pathways involved.

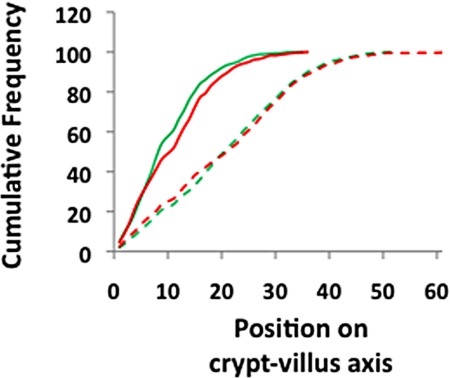

It has been reported that deletion of GSTP results in the increased proliferation of both bone marrow-derived mast cells and embryonic fibroblasts (14, 15). To investigate if there was increased proliferation in the colons of Gstp-null ApcMin mice, migration of enterocytes along the crypt-villus axis was scored after exposure to BrdU for either 2 h or 48 h. No difference between Gstp-wt ApcMin and Gstp-null ApcMin mice was noted in the migration rates of cells along the crypt-villus axis (Fig. 4), as noted by an equivalent shift to the right for both genotypes, indicating similar cellular proliferation rates.

Fig. 4.

No difference in migration of enterocytes in the colons of Gstp-null ApcMin mice. Cumulative frequency plot showing distribution of BrdU-labeled cells along the length of the crypt-villus axis 2 and 48 h after exposure to BrdU. At 2 h there is no difference in distribution between Gstp-wt ApcMin and Gstp-null ApcMin mice. At 48 h, enterocytes in both Gstp-wt ApcMin and Gstp-null ApcMin mice have moved equivalent distances along the axis, indicated by a shift in the graph to the right. For all data, a minimum of three mice were used of each genotype. Solid green and red lines represent Gstp-wt ApcMin and Gstp-null ApcMin mice at 2 h, respectively, while the dashed green and red lines represent Gstp-wt ApcMin and Gstp-null ApcMin mice at 48 h, respectively. For further details, see Materials and Methods.

Increased Inflammation in the Distal Colon of Gstp-Null ApcMin Mice.

mRNA expression profiles within the distal colon were determined by microarray analyses on both Gstp1/p2+/+ and Gstp1/p2−/− animals. In Gstp1/p2−/− colons, the expression of 308 genes was significantly increased and the expression of 202 genes significantly decreased by a factor of twofold or greater. Gstp1 mRNA was found to be absent from Gstp1/p2−/− colon tissue, consistent with deletion of the gene (Table S1). Interestingly, of the overexpressed genes, a significant number were associated with an inflammatory response, including Saa2, Saa1, STAT1, and IL-4, as well as genes involved in immune response, mast-cell proteases Mcpt1, 2, 4, and 9 (see Table S1). Unbiased pathway enrichment profiling of the up-regulated genes confirmed the induction of inflammation-related changes (Table S2). Genes whose expression was reduced in the distal colon of Gstp1/p2−/− mice included genes involved in development, cell adhesion, and the cytoskeleton.

The majority of the inflammation-related changes were also found in the colons of Gstp-null mice carrying the ApcMin mutation (Table S3 and S4). Particular to Gstp-null ApcMin mice, however, were increases in IL-6 (3.2-fold induction) and a 2.8-fold induction in inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS, NOS2), both proteins being implicated in inflammation-mediated carcinogenesis. Repression of the cryptdin related-sequences 2 and 10 (18- and 8-fold, respectively), key molecules in the prevention of bacterial damage to the epithelial cells of the intestine, was also noted. The differences in the profiles between the Gstp-null and Gstp-null ApcMin suggests that there is some crosstalk between the GSTP effects and the ApcMin phenotypes.

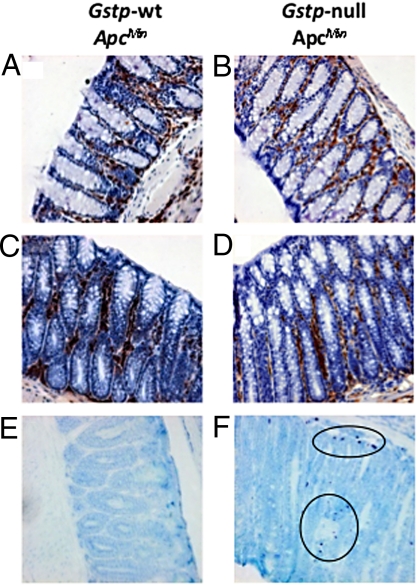

To investigate the inflammatory changes further, we analyzed colon tissue for the presence of mast cells, neutrophils, and macrophages by immunohistochemistry. Substantial numbers of both macrophages (Fig. 5 A and B) and neutrophils (Fig. 5 C and D) were detected in both Gstp-wt ApcMin and Gstp-null ApcMin mice. Consistent with the microarray data (see Table S3), substantially increased levels of mast cells were found in the distal colon of Gstp-null ApcMin mice relative to Gstp-wt ApcMin colons (Fig. 5 E and F).

Fig. 5.

Increased mast cell infiltrates in the Gstp-null ApcMin colon. Immunohistochemical staining of (A, C, and E) Gstp-wt ApcMin and (B, D, and F) Gstp-null ApcMin was carried out to detect immune cell infiltrates. Tissues from both genotypes were found to have substantial infiltration of macrophages (A and B, magnification ×200) and large numbers of neutrophils were also present in both genotypes (C and D, magnification ×200). Greatly increased numbers of mast cell infiltrates were found in the colon of (F) Gstp-null ApcMin mice relative to (E) Gstp-wt ApcMin mice (circles indicate mast cells; magnification ×200). For further details, see Materials and Methods.

In addition to analysis in normal tissue, mRNA profiles were also determined in the colonic adenomas from both Gstp-wt ApcMin and Gstp-null ApcMin mice (Table S5). Although genes were expressed at higher levels in Gstp-null ApcMin vs. Gstp-wt ApcMin adenomas, the differences were relatively small and no differences in activated pathways were clearly identifiable. Interestingly, the differences in cytokines and inflammatory-mediated expression observed in the Gstp-null colon were not found between the adenoma samples, suggesting that the changes arose from the infiltration of inflammatory cells rather than from the epithelial cells themselves. A striking difference between the adenoma samples was the reduction in expression of cryptdin related-sequences. Defcr-rs 2, 10, 7, and 12 were particularly prominent, and all repressed by more than a 100-fold in adenomas from Gtsp-null ApcMin mice.

We have previously described the altered expression of genes involved in mucin production (Gob-5 and Gob-4) in the lungs of Gstp1/p2−/− mice (3). Reduced mucin production in the intestine accompanies both inflammatory bowel disease and colon cancer and has been postulated as allowing irritation of the underlying epithelial cells by the intestinal microbiota (16). To investigate the possibility that altered mucin production, as a consequence of Gstp deletion, was a possible mechanism for the observed increase in inflammation noted in the distal colons of Gstp-null ApcMin mice, we stained colon tissue with alcian blue to detect mucous-producing goblet cells. No difference in goblet cell numbers was noted between Gstp-wt ApcMin and Gstp-null ApcMin distal colon (Fig. 6 A and B).

Fig. 6.

Evidence of increased nitrosative stress in colons of Gstp-null ApcMin mice. Alcian blue staining of goblet cells shows equivalent numbers of goblet cells in the colons of both (A) Gstp-wt ApcMin and (B) Gstp-null ApcMin mice (magnification ×200). Significantly increased levels of nitrotyrosine staining was present in the colon of (D) Gstp-null ApcMin relative to (C) Gstp-wt ApcMin mice following immunohistochemical staining.

Given the increased expression of iNOS in the colon of Gstp-null ApcMin mice (see Table S3), and because changes in nitric oxide production could account for the some of the inflammatory changes observed and the alteration in colon carcinogenesis, we investigated nitrotyrosine levels in the colons of Gstp-wt ApcMin and Gstp-null ApcMin mice. In the absence of Gstp, a profound increase in nitrotyrosine levels was observed (Fig. 6 C and D). The increased production of nitric oxide could also be a consequence of an increased level of oxidative stress; however, no changes in the expression of proteins commonly induced by oxidative stress, including heme oxygenase 1, and NQO1, were found (Fig. S2). We also measured 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-20-deoxyguanosine (8-oxodG) and 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-20-deoxyadenosine (8-oxodA), two of the most common DNA adduct biomarkers for oxidative stress. No difference in either of these DNA adducts was noted between Gstp-wt ApcMin and Gstp-null ApcMin mice (Fig. S3).

Discussion

We have investigated whether GSTP modulates pathways of colon tumorigenesis in a manner which is distinct from its role in the detoxification of carcinogenic electrophiles. The Gstp-null phenotype profoundly increased the incidence, and particularly the multiplicity, of colorectal adenomas in the ApcMin mouse, providing strong evidence that this gene can alter cancer susceptibility by previously unrecorded mechanisms. This in vivo evidence is unique in showing that Gstp can alter tumorigenicity in a model that does not involve carcinogens, and suggests that variation in GSTP expression could influence colon cancer susceptibility. Human GSTP can be regulated by a number of pathways including AP1, retinoic acid, and p53 signaling (17–19). Using a mouse humanized for the Gstp gene, we are currently investigating whether GSTP can be regulated in the colon by chemopreventative agents such as ethoxyquin, butylated hydroxyanisole, and sulforaphane. On this basis, it would be very interesting to evaluate any changes in the incidence of colon cancer in populations receiving chemopreventative agents; for example, there is the trial in Qidong city, China, investigating the potential of Oltipraz to prevent liver cancer (20).

A number of studies have reported an increase in colon adenomas on an ApcMin genetic background; ApcMin: BubR1+/− ApcMin/+ (10-fold increase), Ephb3+/− ApcMin/+ (2-fold increase) and Erβ−/−Min/+ (2.5-fold) (21–23). As reported in the present study, the effects of the absence of Gstp on the ApcMin background appear to be particularly profound with regards to tumor multiplicity (50-fold increase). We have carried out a number of experiments to establish the basis of the increased tumor incidence in Gstp-null ApcMin mice. The absence of Gstp does not appear to alter the level of DNA adducts, or other markers such as heme oxygenase 1 or quinone reductase, resulting from oxidative stress, nor does it increase cell proliferation rates or mucin production in the colonic epithelium. Indeed, the most striking change in the normal colon of Gstp-null ApcMin mice was in pathways linked with inflammatory response, appearing, at least in part, to be related to a significant increase in mast cell infiltration. Mast cells have also been reported as being an essential hematopoietic component of the development of adenomatous polyps (24), and microarray data from this study provided further support for their involvement with significantly increased expression of mast cell-related genes. Increased mast cell numbers have also been observed in patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease, both of which are risk factors in colon cancer susceptibility (25, 26).

Unbiased pathway enrichment analysis of the mRNA profiles suggested significant changes in pathways associated with inflammation. Related to this, normal colonic tissue from Gstp-null ApcMin mice had significantly increased expression of several interleukins (IL-4 and IL-6) and interleukin receptors. Of particular note was the expression of IL-6 (3.2-fold induction), a major proinflammatory cytokine that participates in inflammation-associated carcinogenesis and which has been found to positively correlate with tumor load in colon cancer patients, and promote anchorage-independent growth of human colon carcinoma cells (27, 28). Indicative that this increase in IL-6 gene expression is of biological significance, several pathways known to be modulated by IL-6 signaling, including major inflammatory pathways such as STAT1, IFN-γ, and TGF-β (29–31), were also found to be modulated in the colon of Gstp-null ApcMin mice. Interestingly, such changes in cytokine expression were not observed in the adenomas, suggesting that the changes observed arise—directly or indirectly—from the presence of infiltrating immune cells. There is increasing evidence that GSTP is involved in the regulation of inflammation (32, 33), and recent reports suggest that the Phase-2 family of drug metabolizing enzymes as a whole have a significant role to play in the suppression of inflammation (34).

Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS, NOS2), was increased in the colon of Gstp-null ApcMin mice, and this was reflected in a marked increase in nitrotyrosine protein adducts. There is now strong evidence that NO itself, through its proinflammatory effects, may play an important role in carcinogenesis (35). The increase in iNOS activity may well be a consequence of the proinflammatory environment in the colon of Gstp-null ApcMin mice.

A further potential mechanism for the source of the increased inflammation observed in colonic tissue lacking GSTP is seen in the microarray data, which shows a striking reduction in the expression of cryptdin-related genes, both in normal tissue and in adenomas derived from Gstp-null mice. Cryptdins, known also as α-defensins in humans, are important antibacterial peptides secreted from the Paneth cells in the intestinal crypts, which selectively insert into the membranes of bacteria to create pores and instigate lysis (36). Significantly, a reduction in cryptdin expression is consistently seen in sufferers of inflammatory bowel disease and is thought to result in an imbalance in the amount of virulent bacteria present in the gut, leaving the area prone to immune-mediated intestinal injury (37).

GSTP therefore appears to protect the colon against the development of a pro-inflammatory environment, although the mechanisms by which GSTP may influence such pathways or the inflammatory response remains unclear. However, GSTP can modulate down-stream effector pathways of reactive nitrogen species, including the MAPK signaling cascade, in which JNK, a protein inhibited by GSTP, is an important mediator (5, 38, 39). Another intriguing possibility is the emerging role for GSTP in controlling protein glutathionylation (7).

In conclusion, the Gstp-null ApcMin mouse provides an excellent model for understanding environmental influences on the aetiology of colorectal cancer and could also offer a useful system for investigating the efficacy of novel therapies for the prevention and treatment of this disease.

Methods

Reagents.

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma or Fisher Scientific Ltd..

Animals.

Experiments were undertaken in accordance with the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act of 1986 and approved by the Animal Ethics Committees of the University of Dundee and Cancer Research U.K. Gstp1/p2 null and wild-type mouse lines, on a 129 × MF1 background, were generated and maintained by random inter-crossing to sustain a heterogeneous mixed genetic background as reported in ref. 2. To produce ApcMin/+Gstp1/p2−/− mice (referred to as Gstp-null ApcMin), Gstp1/p2−/− mice were bred with ApcMin mice on a C57BL/6 background to produce ApcMin/+Gstp1/p+/− mice. These mice were then crossed onto either Gstp1/p2−/− or Gstp1/p2+/+ mice to produce ApcMin/+Gstp1/p2−/−, Apc+/+Gstp1/p2−/−, and Apc+/+Gstp1/p2+/+, ApcMin/+Gstp1/p2+/+ (referred to as Gstp-wt ApcMin) respectively. Animals were then either used for experiments or crossed again into Gstp1/p2−/− or Gstp1/p2+/+ mouse genotypes to generate further Gstp-null ApcMin and Gstp-wt ApcMin mice.

Genotyping.

For determination of Gstp genotype PCR was carried-out using tail DNA using the following primers:

For Gstp1, 5′-GGC CAC CCA ACT ACT GTG AT-3′ and 5′-AGA AGG CCA GGT CCT AAA GC-3′, giving a 200-bp band.

For Lac-Z insert, 5′-CTG TAG CGG CTG ATG TTG AA-3′ and 5′-ATG GCG ATT ACC GTT GAT GT-3′, giving a 309-bp band.

For detection of the ApcMin mutation, tail DNA was genotyped using published conditions in ref. 40.

Intestinal Histopathology.

Mice were killed at defined time-points or when showing signs of intestinal neoplasia, such as hunching, pale feet, swollen abdomen, and prolapse. The entire intestine was removed and the small intestine divided into three equal sections, with a fourth section comprising the entire large intestine. Intestine segments were flushed with PBS and opened longitudinally onto Whatmann 3MM paper or made into “Swiss-roll” preparations for detailed histological analyses. Both preparations were fixed overnight at 4 °C in 10% neutral buffered formalin. Adenomas were visualized by staining with 0.2% methylene blue, and identified, counted, and measured with the aid of a Zeiss dissecting microscope with Axiovision imaging software. For detailed histological analysis, H&E sections were prepared from Swiss-roll specimens by standard techniques. To assess mucin production, slides were treated with Alcian Blue (pH 2.5) for 5 min, then mounted using standard techniques.

In Vivo Migration Assays.

In vivo migration was scored as described in ref. 41. To assess rates of in vivo proliferation, cellular proliferation labeling agent (Amersham) containing BrdU was given i.p at 10 μl per gram body weight. Mice were then killed at 2 h and 48 h and Swiss-roll gut preparations produced and fixed as previously described. For each analysis, 25 full crypts were scored from at least three mice of each genotype.

Immunohistochemistry.

To detect BrdU incorporation and nitrotyrosine levels, sections were dewaxed and rehydrated using standard techniques and then underwent microwave antigen retrieval using 10-mM citrate buffer for 10 min. Immunohistochemistry was then carried-out using the Dako Envision staining system with a 1:50 dilution of anti-BrdU antibody (Becton Dickinson) or anti-nitrotyrosine antibody (Millipore). For detection of mast cells, neutrophils and macrophage gut tissue was fixed in methacarn (4:2:1 methanol, chloroform and glacial acetic acid) overnight at 4 °C and in 4% formalin for an additional 24 h. For the detection of mast cells, slides were stained with toluidine blue (pH 2.3) for 5 min. Macrophages were detected by probing appropriately prepared sections with a 1:100 dilution of anti-F4/80 antibody (Abcam) and, similarly, neutrophils detected by probing sections with a 1:1,000 dilution of anti-myeloperoxidase antibody (Dako). Signals were developed by standard techniques.

Isolation of RNA.

To isolate RNA from colon tissue, week-10 mice were killed by cervical dislocation and the last 5 cm of the colon flushed with PBS and immediately snap-frozen. RNA was then isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen) and further purified with an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). The A260/280 ratio of total RNA used was typically ≥1.9. The quality of RNA was assessed by using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies).

Microarray Analysis.

Total RNA (1 μg) was labeled with Cyanine 3 (Cy3)-CTP according to the Agilent One-Color Microarray-Based Gene Expression Analysis protocol version 5.0.1 using the Low Input RNA Fluorescent Linear Amplification Kit (Agilent). Agilent 4 × 44K Whole Mouse Genome Oligo Microarray slides were hybridized and washed using Agilent hybridization and wash buffers, and scanned at 5 μM resolution on an Agilent Microarray Scanner. Images from the scanner were processed using Agilent Feature Extraction Software v9.1. The microarray scanned image and intensity files were imported into Rosetta Resolver gene-expression analysis software version 6.0.0.0.1. Individual expression profiles from the various genotypes (ApcMin/+Gstp1/p2−/−, Apc+/+Gstp1/p2−/−, and Apc+/+Gstp1/p2+/+, ApcMin/+Gstp1/p2+/+) were pooled in silico by calculating an error-weighted mean and compared to build ratios. Data were then analyzed using Bioconductor 2.2 and normalized using quantile normalization. Differential gene expression was assessed between comparison groups using an empirical Bayes t test. Probes that exhibited an adjusted P value of <0.05 and an absolute fold-change of >2 were called differentially expressed. Probes that exhibited an adjusted P value of <0.05 were also used for enrichment analysis using Genego's Metcore pathway tool to identify enriched pathways and biological processes.

Molecular Analysis of Adenomas.

To enable molecular analysis of adenomas, small portions of colorectal adenomas were carefully harvested with the aid of a dissecting microscope to minimize stromal contamination. DNA was then isolated from each adenoma sample using the Wizard SV Genomic Purification System (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For the mutation analysis, selected regions in KRAS and p53 were amplified using the following specific oligonucleotide primers. For p53 mutational analysis, exons 5, 6, and 8 were probed for mutations using the following primers:

Trp53E5-S (5-TCCAATGGTGCTTGGACAATGTG-3),

Trp53E5-AS (5-CCTAAGAGCAAGAATAAGTCAG-3),

Trp53E6-S (5-CTGCTCCGATGGTGATGGTAAG-3),

Trp53E6-AS (5-CTCTAAGCCTAGCTAGCACTCAG-3),

Trp53E8-S (5-CCTTTGGCTGCAGATATGACAAG-3),

Trp53E8-AS (5-TGTGGAAGGAGAGAGCAAGAGGTG-3).

For mutational analysis of KRAS codons 12 or 13, the following primers were used:

KRAS 1S (5-TTATTGTAAGGCCTGCTGAA-3),

KRAS 1AS (5-GCAGCGTTACCTCTATCGTA-3).

PCR products for KRAS and p53 were purified using the QIAGEN PCR purification kit before sequencing. Mutations in codons were detected by direct sequencing using the previously described amplification primers. The sequencing was performed by the DNA Analysis Facility at Ninewells Hospital, Dundee, United Kingdom.

Statistical Analysis.

We performed statistical analyses using GraphPad Quickcalcs Online statistical calculator or SPSS. Significant differences when comparing two groups were determined by unpaired t test. P values were considered significant if they were <0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Catherine Hughes, Jen Kennedy, Sussanne Van Schleven, Simone Weidlich, Sorina Radulescu, and Guenievre Moreaux for technical assistance, Probir Chakravarty for analysis of microarray data, Peter Farmer and Raj Singh for DNA adduct analysis, and members of the C.R.W. laboratory for valuable discussions. This work was funded by Cancer Research U.K.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0911351106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Eaton DL, Bammler TK. Concise review of the glutathione S-transferases and their significance to toxicology. Toxicol Sci. 1999;49:156–164. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/49.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henderson CJ, et al. Increased skin tumorigenesis in mice lacking Pi class glutathione S-transferases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5275–5280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ritchie KJ, et al. Glutathione transferase Pi plays a critical role in the development of lung carcinogenesis following exposure to tobacco-related carcinogens and urethane. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9248–9257. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henderson CJ, et al. Increased resistance to acetaminophen hepatotoxicity in mice lacking glutathione S-transferase Pi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:12741–12745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220176997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adler V, et al. Regulation of JNK signaling by GSTp. EMBO J. 1999;18:1321–1334. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu Y, et al. Human glutathione S-transferase P1–1 interacts with TRAF2 and regulates TRAF2-ASK1 signals. Oncogene. 2006;25:5787–5800. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Townsend DM, et al. Novel role for glutathione S-transferase Pi. Regulator of protein S-Glutathionylation following oxidative and nitrosative stress. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:436–445. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805586200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990;61:759–767. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith G, et al. Mutations in APC, Kirsten-ras, and p53–alternative genetic pathways to colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:9433–9438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122612899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Su LK, et al. Multiple intestinal neoplasia caused by a mutation in the murine homolog of the APC gene. Science. 1992;256:668–670. doi: 10.1126/science.1350108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rubinfeld B, et al. Binding of GSK3beta to the APC-beta-catenin complex and regulation of complex assembly. Science. 1996;272:1023–1026. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5264.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haigis KM, Caya JG, Reichelderfer M, Dove WF. Intestinal adenomas can develop with a stable karyotype and stable microsatellites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:8927–8931. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132275099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luongo C, Moser AR, Gledhill S, Dove WF. Loss of Apc+ in intestinal adenomas from Min mice. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5947–5952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gate L, Majumdar RS, Lunk A, Tew KD. Increased myeloproliferation in glutathione S-transferase Pi-deficient mice is associated with a deregulation of JNK and Janus kinase/STAT pathways. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:8608–8616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308613200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruscoe JE, et al. Pharmacologic or genetic manipulation of glutathione S-transferase P1–1 (GSTpi) influences cell proliferation pathways. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298:339–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linden SK, Sutton P, Karlsson NG, Korolik V, McGuckin MA. Mucins in the mucosal barrier to infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1:183–197. doi: 10.1038/mi.2008.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xia C, Hu J, Ketterer B, Taylor JB. The organization of the human GSTP1–1 gene promoter and its response to retinoic acid and cellular redox status. Biochem J. 1996;313:155–161. doi: 10.1042/bj3130155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xia C, Taylor JB, Spencer SR, Ketterer B. The human glutathione S-transferase P1–1 gene: modulation of expression by retinoic acid and insulin. Biochem J. 1993;292:845–850. doi: 10.1042/bj2920845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lo HW, et al. Identification and functional characterization of the human glutathione S-transferase P1 gene as a novel transcriptional target of the p53 tumor suppressor gene. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:843–850. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang JS, et al. Protective alterations in phase 1 and 2 metabolism of aflatoxin B1 by oltipraz in residents of Qidong, People's Republic of China. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:347–354. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.4.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rao CV, et al. Colonic tumorigenesis in BubR1+/-ApcMin/+ compound mutant mice is linked to premature separation of sister chromatids and enhanced genomic instability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:4365–4370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407822102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Batlle E, et al. EphB receptor activity suppresses colorectal cancer progression. Nature. 2005;435:1126–1130. doi: 10.1038/nature03626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cho NL, Javid SH, Carothers AM, Redston M, Bertagnolli MM. Estrogen receptors alpha and beta are inhibitory modifiers of Apc-dependent tumorigenesis in the proximal colon of Min/+ mice. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2366–2372. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gounaris E, et al. Mast cells are an essential hematopoietic component for polyp development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19977–19982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704620104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andoh A, et al. Immunohistochemical study of chymase-positive mast cells in inflammatory bowel disease. Oncol Rep. 2006;16:103–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He SH. Key role of mast cells and their major secretory products in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:309–318. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i3.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chung YC, Chang YF. Serum interleukin-6 levels reflect the disease status of colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2003;83:222–226. doi: 10.1002/jso.10269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schneider MR, et al. Interleukin-6 stimulates clonogenic growth of primary and metastatic human colon carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2000;151:31–38. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(99)00401-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Becker C, et al. TGF-beta suppresses tumor progression in colon cancer by inhibition of IL-6 trans-signaling. Immunity. 2004;21:491–501. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McLoughlin RM, et al. Interplay between IFN-gamma and IL-6 signaling governs neutrophil trafficking and apoptosis during acute inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:598–607. doi: 10.1172/JCI17129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hong F, et al. Opposing roles of STAT1 and STAT3 in T cell-mediated hepatitis: Regulation by SOCS. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1503–1513. doi: 10.1172/JCI15841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo L, et al. Recombinant protein glutathione S-transferases P1 attenuates inflammation in mice. Mol Immunol. 2008;46:848–857. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou J, et al. Glutathione transferase P1: an endogenous inhibitor of allergic responses in a mouse model of asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:1202–1210. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200801-178OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dinkova-Kostova AT, Talalay P. Direct and indirect antioxidant properties of inducers of cytoprotective proteins. Mol Nutr Food Res 52 Suppl. 2008;1:S128–S138. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hussain SP, et al. Nitric oxide is a key component in inflammation-accelerated tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7130–7136. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bevins CL. Paneth cell defensins: key effector molecules of innate immunity. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:263–266. doi: 10.1042/BST20060263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramasundara M, Leach ST, Lemberg DA, Day AS. Defensins and inflammation: the role of defensins in inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:202–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shaulian E, Karin M. AP-1 as a regulator of cell life and death. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:E131–E136. doi: 10.1038/ncb0502-e131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hussain SP, Harris CC. Inflammation and cancer: an ancient link with novel potentials. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:2373–2380. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dietrich WF, et al. Genetic identification of Mom-1, a major modifier locus affecting Min-induced intestinal neoplasia in the mouse. Cell. 1993;75:631–639. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90484-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sansom OJ, et al. Loss of Apc in vivo immediately perturbs Wnt signaling, differentiation, and migration. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1385–1390. doi: 10.1101/gad.287404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.