Abstract

The institutionalization of individuals with mental illness in nursing homes is an important policy concern. Using nursing home Minimum Data Set assessments from 2005, we found large cross-state variation in both the rates of mental illness among nursing home admissions and the estimated rates of nursing home admissions among persons with mental illness. We also found that newly admitted individuals with mental illness were younger and more likely to become long-stay residents. Taken together, these results suggest that state-level mental health and nursing home factors may influence the likelihood of long-term nursing home use for persons with mental illness.

Over 500,000 persons with mental illness (excluding dementia) reside in US nursing homes on a given day, significantly exceeding the number in all other health care institutions combined.1 Mental illness is one, and sometimes the decisive, factor contributing to placement in a nursing home.2 A key issue of importance for policymakers and mental health advocates is the appropriateness of nursing home admission for individuals with mental illnesses. Nursing homes have become the de facto mental institution for many persons with mental illness as a result of the dramatic downsizing and closure of state psychiatric hospitals spurred on by the deinstitutionalization movement. However, it is questionable whether nursing homes are equipped to serve the unique needs of residents with chronic mental illnesses.

The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) of 1987 was a major policy reform directed at the screening and assessment of individuals with mental illness targeted for nursing home care. These regulations mandated a Pre-Admission Screening and Annual Resident Review (PASRR) to identify nursing home applicants and residents with mental illness. Under the PASRR program, nursing facilities are prohibited from admitting any individual with a serious mental illness unless the State Mental Health Authority determines that nursing home level care is required for that individual.3 Further, PASRR is used to determine whether specialized mental health services are needed for nursing home residents. However, fewer than half of nursing home residents with a major mental illness receive appropriate preadmission screening according to the DHHS Office of the Inspector General.4 Given the implementation of PASRR at the state-level, along with varying state mental health and nursing home resources and policies, there has been concern that individuals with mental illnesses are admitted to nursing homes at different rates across states.5 However, previous research has not addressed this issue.

Using data from various sources, we estimate the cross-state variation in the proportion of nursing home admissions indicating a mental illness, and the proportion of persons with mental illness admitted to nursing homes. The first measure is important for nursing home policymakers and the second for mental health policymakers.

METHODS

Data and Study Population

We used the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) national registry of nursing home resident assessments from the Minimum Data Set (MDS) to examine the prevalence of newly admitted nursing home residents ages 18 and over who indicated a mental illness at the time of admission. The MDS is the congressionally mandated assessment conducted for all residents of Medicare/Medicaid certified nursing facilities upon admission and at least quarterly thereafter.6 New admissions were defined as those residents with an admission assessment during calendar year 2005, for whom no MDS record as far back as January 1, 1999 existed in the registry, implying an individual’s first admission to a nursing home. A total of 1,150,734 residents 18 years or older were newly admitted during 2005. In order to track transitions to long-stay status (90+ days in the facility), we used new admissions from 2004 in order to ensure complete follow-up.

Definition of Mental Illness

For all newly admitted nursing home residents in 2005, we defined mental illness based upon the diagnosis fields in the MDS assessment at the time of admission. From this form, we identified individuals with mental illness using four diagnoses: schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression and anxiety (Section I1dd, I1ee, I1ff, or I1gg indicated on the admission MDS form). These fields are entered by an MDS assessment nurse using the patient’s medical charts. In a recent analysis, these fields in the MDS admission form were found to be internally consistent in terms of demographics, co-morbidities and treatments received.7 However, we acknowledge that the MDS falls significantly short of clinical measures of mental illness [e.g., Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV)]. We constructed a “broad” definition of mental illness using all four diagnoses and a “narrow” definition encompassing only schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Our narrow definition includes the two psychiatric disorders considered the most disabling and most frequently associated with serious mental illness and, consequently, institutionalization among persons with mental illness.

State-based Estimates of Mental illness

There are various approaches to estimating the prevalence of persons with mental illness across states. For example, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA) estimates the number of persons with serious mental illness in each state by applying a national rate of mental illness (e.g., 5.4% in 2007) to each state’s population. In this study, we opted to use estimates of the numbers of adults (age 18 and over) with serious mental illness in each state based on the work of Holzer and colleagues at the University of Texas Medical Branch.8 Their estimates are drawn from the National Institute of Mental Health’s Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (CPES), which provide data on the distributions, correlates, and risk factors of mental disorders among the general population, with special emphasis on minority groups. A synthetic estimation approach is then applied in which these risk factors (age, race, gender, etc.) are used to construct the prevalence of persons with a serious mental illness based on their overall distribution within each state.9 Thus, unlike the SAMSHA approach which applies a uniform rate of mental illness across states, this approach allows for variation in the estimates across states based on risk factors present in the state’s population. Holzer’s operational definition of serious mental illness requires that the respondent’s age of onset be at least one year prior to the date of the survey, and that the respondent has experienced significant functional limitations due to the mental disorder over the past year.

Importantly, this synthetic estimation approach differs from both the narrow and broad nursing home-based measures of mental illness available from the MDS. Although the measures are different, we assert that the population-based estimate can serve as a meaningful denominator for the MDS-based measures across states, regardless of the “narrowness” of the definition. We have no reason to believe that there is any specific bias in the nursing home or population measures across states.

Analytic Approach

Using both the narrow and broad definitions of mental illness, we computed two different measures of mental illness prevalence both nationally and for each of the 48 contiguous U.S. states. First, we computed the proportion of persons with mental illness among all new nursing home admissions. Next, we calculated the proportion of persons with mental illness living in the state (or country) admitted to nursing homes. Results based on the “narrow” definition can be viewed as lower-bound estimates, and those based on the “broad” definition as approximating upper-bound estimates, although we acknowledge the potential for mismatch between the definitions of mental illness in nursing homes and Holzer’s definition for the population. As such, we focus the discussion of results largely around those applying the more conservative “narrow” definition of mental illness in nursing homes.

One concern among policymakers, especially in regards to PASRR implementation and oversight, has been the admission of younger persons with mental illness into nursing homes.10 Thus, we present a comparison of the age distributions at admission for three cohorts: mental illness (narrow), mental illness (broad), and no mental illness. Finally, policymakers are also concerned about the transition of persons with mental illness into “long-stay” nursing home residents. As such, we compare the likelihood of still being present in the nursing home at 90 days for the narrow, broad and no mental illness cohorts.

RESULTS

Mental Illness among Nursing Home Admissions

In 2005, there were 1,150,734 new nursing home admissions in the entire U.S. (see Exhibit 1). Of these admissions, 31,335 (2.7%) indicated schizophrenia or bipolar disorder (narrow mental illness definition), and 315,003 (27.4%) indicated schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression or anxiety (broad mental illness definition). The states with the lowest rates of nursing home admissions with a mental illness, narrowly defined, were Wyoming (1.2%), South Dakota (1.6%), and Florida (1.9%) and the states with the highest rates were Illinois (3.7%), California (3.5%), Louisiana (3.4%), and Missouri (3.4%). When depression and anxiety were included, the states with the lowest proportion of nursing home admissions with mental illness were Connecticut (22.2%), New Jersey (20.6%), and Utah (20.4%), and the states with the highest rates were Maine (36.2%), Kansas (34.5%) and New Hampshire (33.9%). As suggested by the different states at the tails of the two measures, there was almost no relationship (Pearson correlation, 0.03) between the narrow and broad mental illness measures when applied to new nursing home admissions aggregated to the state level.

EXHIBIT 1.

Prevalence of mental illness (MI) among new nursing home admissions age 18+, 2005

| STATE | Total new NH admissions (N) |

Of N, cases with MI |

Total 18+ population with serious MI |

New NH admissions with MI as % of nestimate |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nnarrow | % | nbroad | % | nestimate | nnarrow | nbroad | ||

| NATIONAL | 1,150,734 | 31,335 | 2.7 | 315,003 | 27.4 | 10,453,690 | 0.300 | 3.013 |

| AL | 17,738 | 458 | 2.6 | 4,929 | 27.8 | 186,095 | 0.246 | 2.649 |

| AR | 10,695 | 214 | 2.0 | 2,867 | 26.8 | 116,038 | 0.184 | 2.471 |

| AZ | 17,835 | 487 | 2.7 | 4,933 | 27.7 | 215,655 | 0.226 | 2.287 |

| CA | 99,020 | 3,487 | 3.5 | 25,452 | 25.7 | 1,170,000 | 0.298 | 2.175 |

| CO | 13,584 | 395 | 2.9 | 4,301 | 31.7 | 154,770 | 0.255 | 2.779 |

| CT | 21,582 | 585 | 2.7 | 4,789 | 22.2 | 109,418 | 0.535 | 4.377 |

| DE | 3,405 | 84 | 2.5 | 983 | 28.9 | 28,389 | 0.296 | 3.463 |

| FL | 84,707 | 1,642 | 1.9 | 23,426 | 27.7 | 658,066 | 0.250 | 3.560 |

| GA | 22,273 | 660 | 3.0 | 5,549 | 24.9 | 344,365 | 0.192 | 1.611 |

| IA | 14,293 | 305 | 2.1 | 3,982 | 27.9 | 105,138 | 0.290 | 3.787 |

| ID | 5,088 | 121 | 2.4 | 1,573 | 30.9 | 53,616 | 0.226 | 2.934 |

| IL | 55,035 | 2,055 | 3.7 | 13,279 | 24.1 | 420,948 | 0.488 | 3.155 |

| IN | 28,641 | 639 | 2.2 | 7,281 | 25.4 | 226,649 | 0.282 | 3.212 |

| KS | 10,458 | 323 | 3.1 | 3,603 | 34.5 | 94,905 | 0.340 | 3.796 |

| KY | 17,457 | 472 | 2.7 | 5,203 | 29.8 | 180,436 | 0.262 | 2.884 |

| LA | 13,944 | 470 | 3.4 | 3,891 | 27.9 | 181,766 | 0.259 | 2.141 |

| MA | 34,352 | 1,030 | 3.0 | 9,778 | 28.5 | 210,106 | 0.490 | 4.654 |

| MD | 24,990 | 647 | 2.6 | 6,452 | 25.8 | 176,104 | 0.367 | 3.664 |

| ME | 6,971 | 169 | 2.4 | 2,524 | 36.2 | 51,771 | 0.326 | 4.875 |

| MI | 37,285 | 970 | 2.6 | 11,433 | 30.7 | 349,949 | 0.277 | 3.267 |

| MN | 23,369 | 609 | 2.6 | 7,142 | 30.6 | 167,328 | 0.364 | 4.268 |

| MO | 25,701 | 862 | 3.4 | 7,625 | 29.7 | 222,089 | 0.388 | 3.433 |

| MS | 8,608 | 263 | 3.1 | 2,603 | 30.2 | 125,624 | 0.209 | 2.072 |

| MT | 4,001 | 110 | 2.7 | 1,126 | 28.1 | 38,486 | 0.286 | 2.926 |

| NC | 32,916 | 728 | 2.2 | 8,052 | 24.5 | 328,877 | 0.221 | 2.448 |

| ND | 3,473 | 79 | 2.3 | 1,061 | 30.5 | 23,807 | 0.332 | 4.457 |

| NE | 8,243 | 219 | 2.7 | 2,664 | 32.3 | 60,711 | 0.361 | 4.388 |

| NH | 5,375 | 139 | 2.6 | 1,821 | 33.9 | 43,188 | 0.322 | 4.216 |

| NJ | 45,228 | 1,025 | 2.3 | 9,308 | 20.6 | 260,624 | 0.393 | 3.571 |

| NM | 5,704 | 169 | 3.0 | 1,667 | 29.2 | 70,906 | 0.238 | 2.351 |

| NV | 5,009 | 146 | 2.9 | 1,483 | 29.6 | 86,858 | 0.168 | 1.707 |

| NY | 79,022 | 2,041 | 2.6 | 18,635 | 23.6 | 671,192 | 0.304 | 2.776 |

| OH | 65,255 | 2,148 | 3.3 | 19,024 | 29.2 | 419,734 | 0.512 | 4.532 |

| OK | 12,566 | 314 | 2.5 | 3,951 | 31.4 | 146,072 | 0.215 | 2.705 |

| OR | 12,515 | 325 | 2.6 | 3,185 | 25.4 | 136,043 | 0.239 | 2.341 |

| PA | 66,296 | 1,665 | 2.5 | 20,050 | 30.2 | 449,662 | 0.370 | 4.459 |

| RI | 5,547 | 150 | 2.7 | 1,385 | 25.0 | 38,026 | 0.394 | 3.642 |

| SC | 13,805 | 326 | 2.4 | 3,844 | 27.8 | 167,589 | 0.195 | 2.294 |

| SD | 3,356 | 55 | 1.6 | 1,037 | 30.9 | 29,857 | 0.184 | 3.473 |

| TN | 26,798 | 769 | 2.9 | 7,684 | 28.7 | 242,360 | 0.317 | 3.170 |

| TX | 62,586 | 1,547 | 2.5 | 16,909 | 27.0 | 821,804 | 0.188 | 2.058 |

| UT | 6,987 | 194 | 2.8 | 1,426 | 20.4 | 79,042 | 0.245 | 1.804 |

| VA | 26,473 | 617 | 2.3 | 7,705 | 29.1 | 260,980 | 0.236 | 2.952 |

| VT | 2,458 | 81 | 3.3 | 813 | 33.1 | 22,929 | 0.353 | 3.546 |

| WA | 24,680 | 739 | 3.0 | 7,786 | 31.5 | 217,035 | 0.341 | 3.587 |

| WI | 26,081 | 578 | 2.2 | 7,836 | 30.0 | 187,396 | 0.308 | 4.182 |

| WV | 7,528 | 202 | 2.7 | 2,456 | 32.6 | 81,765 | 0.247 | 3.004 |

| WY | 1,801 | 22 | 1.2 | 497 | 27.6 | 19,522 | 0.113 | 2.546 |

Sources: All data are from authors’ calculations using the Minimum Data Set except the “Total 18+ population with serious MI” column, which was obtained from the work of Dr. Charles Holzer (see: psy.utmb.edu)

Nursing Home Admissions among Persons with Mental Illness

Based on the Holzer synthetic estimation technique, there are over 10.4 million adults in the U.S. with a mental illness (see Exhibit 1). Using this estimate as a denominator, between 0.3% (narrow) and 3% (broad) of the population with mental illness was admitted a nursing home in 2005. Once again, there was significant cross-state variation in both the narrow and broad measures. When applying the narrow definition, the states with the lowest proportions of new nursing home admissions with mental illness were Wyoming (0.11%), Nevada (0.17%), Arkansas (0.18%) and South Dakota (0.18%) and the states with the highest rates were Connecticut (0.54%), Ohio (0.51%) and Massachusetts (0.49%). When applying the broad definition, Georgia (1.6%), Nevada (1.7%) and Utah (1.8%) had the lowest rates and Maine (4.9%), Massachusetts (4.7%) and Ohio (4.5%) had the highest rates. When applied to the overall population with mental illness, there was a strong relationship (Pearson correlation, 0.72, p<.001) between the narrow and broad measures.

In order to better understand the considerable variation of admissions across states, we can apply the rates of admission in the highest and lowest states to the entire U.S. Once again, there were 31,335 new nursing home admissions for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in 2005, accounting for 0.3% of the 10.4 million persons with mental illness nationwide. If the 0.11% admission rate in Wyoming was applied to the entire country, then 19,522 fewer admissions would have occurred in 2005. Similarly, if every state admitted 0.54% of these cases as in Connecticut, there would have been 24,592 additional admissions in 2005.

Age Distribution

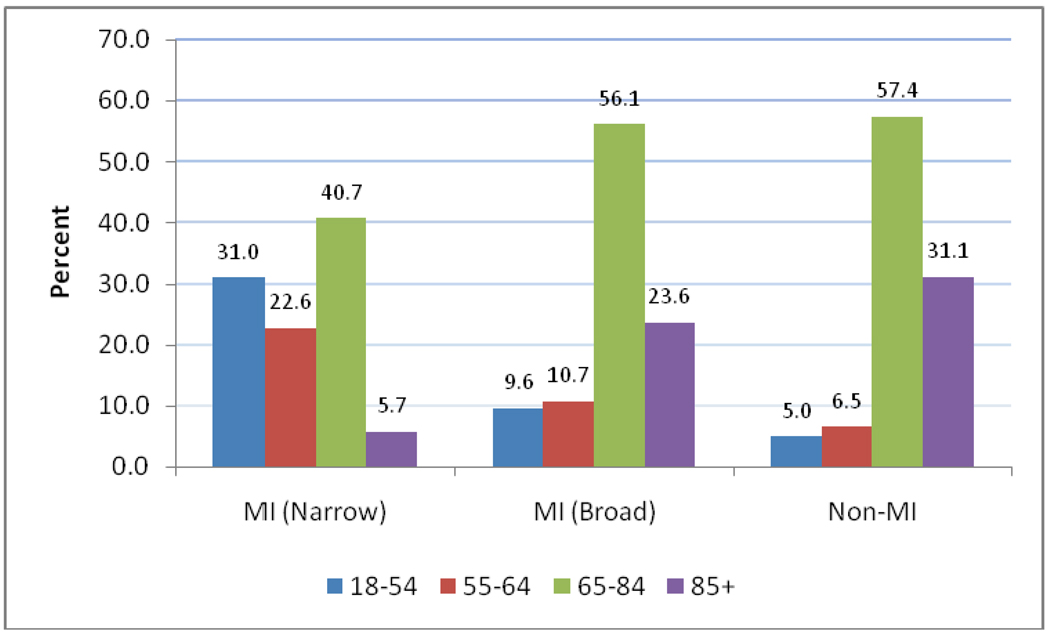

The average age across all new nursing home admissions in 2005 was 77 (SD = 12), with only 14% of individuals below age 65. By comparison, the average age at first admission for individuals with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder was 62 (SD = 15). Among new admissions for these two conditions, a high percentage (54%) occurred among non-elderly (ages 18–64) individuals, with 23% concentrated among the near elderly (ages 55–64) (see Exhibit 2). In 2005, there were 16,796 individuals ages 18–64 admitted nationwide for schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

EXHIBIT 2.

New nursing home admissions by age categories among persons withmental illness (MI) (narrow), MI (broad), and no MI, 2005

|

Source: All data are from authors’ calculations using the Minimum Data Set

Transitions to Long-Stay Status

Persons with mental illness newly admitted to a nursing home were more likely to remain in the nursing home at least 90 days after admission relative to those without mental illness (see Exhibit 3). Using all new admissions from 2004, 45.6% (narrow definition) and 32.6% (broad definition) of persons with mental illness were still in the facility at 90 days. By comparison, only 24.1% of individuals without a mental illness diagnosis still resided in the facility at 90 days. There was significant cross-state variation in the rate of transition to long-stay status. Among those meeting the narrow definition, the long-stay transition rates ranged from 26.3% (Oregon) to 62.3% (Mississippi). For those meeting the broad mental illness definition, long-stay transition rates ranged from 19.7% (Oregon) to 52.5% (Louisiana).

EXHIBIT 3.

Percent new nursing home admissions (during 2004) becoming long-stay, by Mental Illness (MI) status

| MI: Narrow (N=31,610) |

MI: Broad (N=315,188) |

MI: None (N=851,537) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| NATIONAL | 45.6 | 32.6 | 24.1 |

| AL | 48.7 | 32.7 | 27.1 |

| AR | 55.9 | 48.5 | 32.0 |

| AZ | 30.0 | 20.0 | 14.1 |

| CA | 43.2 | 29.1 | 20.6 |

| CO | 46.4 | 31.0 | 23.5 |

| CT | 44.2 | 30.2 | 20.1 |

| DE | 48.1 | 30.4 | 22.3 |

| FL | 33.5 | 23.3 | 16.9 |

| GA | 59.1 | 42.6 | 35.6 |

| IA | 55.6 | 45.7 | 34.0 |

| ID | 39.7 | 30.7 | 19.8 |

| IL | 54.8 | 35.2 | 22.4 |

| IN | 47.8 | 36.1 | 26.7 |

| KS | 55.2 | 44.7 | 34.9 |

| KY | 48.5 | 37.3 | 27.9 |

| LA | 61.9 | 52.5 | 38.3 |

| MA | 41.0 | 30.7 | 21.0 |

| MD | 37.3 | 26.3 | 18.5 |

| ME | 29.7 | 24.7 | 17.8 |

| MI | 41.0 | 30.2 | 25.6 |

| MN | 41.4 | 31.5 | 25.1 |

| MO | 52.3 | 38.4 | 26.9 |

| MS | 62.3 | 51.2 | 35.5 |

| MT | 42.6 | 34.9 | 25.8 |

| NC | 45.7 | 35.3 | 27.8 |

| ND | 47.5 | 46.6 | 36.6 |

| NE | 47.2 | 38.9 | 28.6 |

| NH | 43.1 | 35.2 | 24.5 |

| NJ | 43.5 | 26.5 | 17.9 |

| NM | 44.2 | 32.6 | 23.5 |

| NV | 47.0 | 31.7 | 23.4 |

| NY | 54.5 | 35.9 | 27.7 |

| OH | 42.0 | 30.8 | 21.6 |

| OK | 60.8 | 45.4 | 34.2 |

| OR | 26.3 | 19.7 | 13.8 |

| PA | 45.1 | 32.2 | 23.9 |

| RI | 44.6 | 32.9 | 25.1 |

| SC | 48.9 | 34.1 | 26.6 |

| SD | 56.1 | 48.4 | 40.7 |

| TN | 42.5 | 31.6 | 25.3 |

| TX | 52.4 | 41.1 | 31.5 |

| UT | 45.8 | 25.0 | 21.0 |

| VA | 43.6 | 30.0 | 23.2 |

| VT | 35.5 | 33.9 | 28.9 |

| WA | 30.3 | 22.9 | 16.7 |

| WI | 35.7 | 31.9 | 26.5 |

| WV | 49.0 | 33.1 | 21.9 |

| WY | 46.2 | 40.9 | 31.9 |

Source: All data are from authors’ calculations using the Minimum Data Set.

DISCUSSION

There is significant variation across states in the nursing home admission of persons with mental illness. Moreover, persons with mental illness are significantly younger than other nursing home residents and more likely to transition to long-stay status. These results highlight a need for further research to better understand the cross-state variation in nursing home admissions for persons with mental illness. This variation may relate to different nursing home and mental health factors across states.

Medicaid is the dominant payer of nursing home services, and there is considerable discretion across states in the method and generosity of payment.11 In theory, Medicaid payment policies may relate to the varying nursing home admission of persons with mental illness across states. The most common system used to case-mix adjust Medicaid payments to nursing homes is the Resource Utilization Groups (RUGs) system.12 Based on clinical characteristics, RUGs divides individuals into 44 (or 34, depending on Versions used) Medicaid payment groups. Mental illness is incorporated in two ways. First, for individuals with “clinically complex” conditions (e.g., pneumonia, dehydration, chemotherapy), a higher rate is paid in the presence of depression. Second, individuals with behavioral problems such as wandering, hallucinations and delusions can qualify for a higher rate, but only if their physical problems are minimal. In other words, for individuals with more extensive physical problems requiring assistance with multiple deficits in activities of daily living, there is no additional payment for the presence of behavioral problems. All else equal, these payment rules may incentivize the admission of less physically disabled persons with mental illness, particularly if treatments are not expensive.

The cross-state variation in nursing home admissions for persons with mental illness may also relate to state efforts to “rebalance” their long-term care systems away from nursing homes and towards home- and community-based services (HCBS). As part of the Deficit Reduction Act (DRA) of 2005, the DHHS initiated a program under which CMS has awarded grants to states totaling $1.4 billion over the five-year period 2007–2011 to provide alternatives to nursing home care. Of interest to mental health advocates is that states may not restrict access to HCBS on the basis of disability or diagnosis under the DRA. This had been a longstanding dilemma in Medicaid mental health policy.13 In efforts to rebalance long-term care, certain states have invested more heavily than others in Medicaid HCBS waiver programs.14 Clearly, some of the state investment in HCBS alternatives may create additional community-living opportunities for persons with mental illness.

As an important point, this is not to suggest that all persons with mental illness are candidates for transfer out of the nursing home. Individuals in nursing homes with chronic psychiatric conditions have greater cognitive and functional deficits, as well as more behavioral problems, when compared with community-dwelling persons with the same psychiatric condition.15 Although it is debatable as to whether nursing homes are the best institutional model to deliver services for these individuals, there are likely a small minority of patients who cannot survive outside a full-care psychiatric institution.16 However, similar to elderly nursing home residents and the recent rebalancing effort, there may be potential candidates for nursing home discharge if community mental health services were expanded.

A third potential explanation for the large cross-state variation in the admission of nursing home residents with mental illness is the state’s adherence to the PASRR requirements. PASRR involves two parts: preadmission level I and level II screens. Level I screens are used to identify Medicaid recipients applying for new nursing home admission who may have a serious mental illness (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression). If suspected of having a serious mental illness, applicants then undergo a Level II evaluation of their physical and mental health status to verify whether they have a serious mental illness. For applicants diagnosed with a serious mental illness, an independent evaluator, with no ties to the nursing facility or State Mental Health Authority, is used to determine whether the applicant requires nursing home level care and/or whether specialized mental health services are needed.17

Although these guidelines are national, there is considerable room for discretion and interpretation in the implementation of the rules at the state level. For example, Ohio, one of the states we documented with a high rate of nursing home admissions indicating a mental illness, uses the hospital (convalescent) exemption that allows a bypass of the PASRR requirements. Individuals discharged following an acute hospital stay are able to gain admission to nursing homes for the treatment of the same condition for which they were treated in the hospital for up to 30 days, through the certification of an attending physician. In both Ohio and other states, we found a large proportion of nursing home admissions with mental illness ultimately become long-stay residents. Thus, in spite of the best intentions of the PASRR rules, a number of persons with mental illness are gaining admission to nursing homes in Ohio, and other states that use this exemption, without being screened for mental illness.

Finally, the cross-state variation in nursing home admissions indicating a mental illness may also be related to the mental health infrastructure. Although specialized state psychiatric hospitals have closed in many states, these hospitals continue to care for tens of thousands persons with major mental illnesses. Clearly, the differential presence of these hospitals across states will influence whether individuals with mental illness ultimately are admitted to nursing homes. A 1999 Supreme Court ruling on the Olmstead case found that states have an obligation under the Americans with Disabilities Act to administer services, programs, and activities in the most integrated setting appropriate to individuals’ needs. Currently, several states have Olmstead cases pending against them for the inappropriate admission of persons with mental illness into nursing homes. Interestingly, Connecticut, the state we estimated to have the highest rate (0.54%) of persons with mental illness (narrowly defined) in nursing homes, and Illinois, the state we estimated to have the highest rate (3.7%) of nursing home admissions with mental illness (narrowly defined), both have cases pending.18 The lawsuit against the state of Connecticut alleges that more than 200 people with mental illnesses were “needlessly segregated and inappropriately warehoused” in three Connecticut nursing homes.19 The Illinois lawsuit is a class action suit on behalf of the 5,000 state-funded individuals housed in 27 private for-profit nursing homes within the state.

We found that a high percentage (54%) of persons entering nursing homes with mental illness (narrowly defined) were between the ages of 18–64. Both mental health advocates and researchers have long pointed to an inadequate system of care and a lack of appropriate community-based residential services as major obstacles to helping adults with mental illnesses leave institutional settings and succeed in the community, and in preventing inappropriate institutionalization.20 Persons with serious mental illness face a fragmented and underfunded system of care that does not sufficiently provide the safety net needed for vulnerable individuals trying to live in less restrictive and more independent environments.21 They must negotiate multiple and distinct systems of care, including medical care, mental health care, and aging services, each with its own operating principles.22 Perhaps this is why those with persistent serious mental illness newly admitted to the nursing home were much more likely to become long-stay residents relative to other newly admitted residents. Without a critical safety net of community supports in place, persons with serious mental illness may face a substantial risk of nursing home placement at any age. There is clearly an urgent need for future research on mental health policies that facilitate community-based supports for persons with serious mental illness across the lifespan.

This analysis is limited in several ways. First, the MDS depends on assessment nurses accurately recording the information. Studies have generally confirmed the reliability and validity of these data, with some variability across nursing homes.23 If anything, one would generally expect there to be an underreporting of mental health diagnoses rather than an over-reporting. The potential under-diagnosis of mental illnesses such as schizophrenia may be related to the onset of dementia among these individuals in later life, which may mask the underlying schizophrenia.24 We do not, however, have a reason to suspect that there is any systematic variation across states in the recording of mental illness diagnoses. Second, we constructed our sample based on first-time nursing home admissions rather than a single cross-section of residents at a given point in time. As such, our data examine the flow of residents into nursing homes rather than the cumulative number of persons with mental illness receiving services. Finally, it is important to acknowledge, once again, that mental illness among nursing home admissions is defined differently relative to mental illness among the general population. In spite of these differences, we do not expect there to be systematic biases across states in calculating the proportion of persons with mental illness admitted to nursing homes.

In sum, persons with mental illness in nursing homes are a large, vulnerable and under-studied population. This paper has provided data suggesting large cross-state variation in the admission of individuals with a mental illness in the nursing home setting. Future research will need to consider the underlying reasons for this variation and the appropriateness of nursing home admission for individuals with mental illnesses.

Footnotes

This work was supported with funding from the National Institute on Aging (NIA) under Grant numbers R01 AG23622 and P01 AG27296. David Grabowski was supported in part by an NIA career development award (Grant no.K01AG24403). Kelly Aschbrenner was supported by an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) postdoctoral training program grant (no. 5T32 HS000011). Data were made available by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services under Data Use Agreement no. 15293.

Contributor Information

David C. Grabowski, Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, grabowski@med.havard.edu.

Kelly A. Aschbrenner, Center for Gerontology and Health Care Research, Department of Community Health, Brown University.

Zhanlian Feng, Center for Gerontology and Health Care Research, Department of Community Health, Brown University.

Vincent Mor, Department of Community Health, Brown University.

NOTES

- 1.Fullerton CA, et al. Working Paper, Harvard Medical School. Boston, MA: 2008. Trends in Mental Health Admissions to Nursing Homes: 1999–2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black BS, Rabins PV, German PS. Predictors of Nursing Home Placement among Elderly Public Housing Residents. Gerontologist. 1999;39(no 5):559–568. doi: 10.1093/geront/39.5.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linkins K, et al. Screening for Mental Illness in Nursing Facility Applicants: Understanding Federal Requirements. Rockville, MD: Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2001. SAMHSA Publication No. (SMA) 01-3543. [Google Scholar]

- 4.OIG. Younger Nursing Facility Residents with Mental Illness: Preadmission Screening and Resident Review (Pasrr) Implementation and Oversight. Rockville, MD: Office of the Inspector General, Department of Health and Human Services; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linkins KW, et al. Use of Pasrr Programs to Assess Serious Mental Illness and Service Access in Nursing Homes. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57(no 3):325–332. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.3.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris JN, et al. Designing the National Resident Assessment Instrument for Nursing Homes. Gerontologist. 1990;30(no 3):293–307. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fullerton, et al. Trends in Mental Health Admissions to Nursing Homes: 1999–2005. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.7.965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The state estimates used in this study are available online (see psy.utmb.edu). For a description of the general methodology used to derive these estimates, see: Holzer CE, Jackson DJ, Tweed D. Horizontal Synthetic Estimation: A Strategy for Estimating Small Area Health Related Characteristics. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1981;4(no 1):29–34.

- 9.Importantly, the Holzer definition of serious mental illness roughly parallels the definition used by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Specifically, the Holzer definition of serious mental illness (termed MHM2) includes a minimum impairment score, a minimum number of disability days, and then a range of chronic conditions including bipolar I and II, mania, major depression with hierarchy, Dysthymia hierarchy, generalized anxiety, hypomania, major depressive episode, panic disorder, post traumatic stress disorder, Agoraphobia with/without panic, social phobia and specific phobia. Importantly, although schizophrenia is not specifically accounted for by this measure, an individual with schizophrenia would typically be included under one of the other criteria. Also, we opted to use Holzer’s estimates of serious mental illness, because his more narrow definition of “severe and persistent mental illness” (MHM1) excluded both generalized anxiety and major depressive episode, and his broader definitions (MHM3 and MHM4) included individuals with current (rather than only chronic) conditions.

- 10.Office of Inspector General, Younger Nursing Facility Residents with Mental Illness: Pre-Admission Screening and Resident Review (Pasrr). Implementation and Oversight. Washington, D.C.: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2001.

- 11.Grabowski DC, et al. Recent Trends in State Nursing Home Payment Policies. Health Affairs W4. 2004:w363–w373. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w4.363. published online 16 June 2004; 10.1377/hlthaff.w4.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng Z, et al. Medicaid Payment Rates, Case-Mix Reimbursement, and Nursing Home Staffing-1996–2004. Medical Care. 2008;46(no 1):33–40. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181484197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koyanagi C. The Deficit Reduction Act: Should We Love It or Hate It? Psychiatric Services. 2006;57(no 12):1711–1712. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.12.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitchener M, et al. Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services: National Program Trends. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24(no 1):206–212. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartels SJ, Mueser KT, Miles KM. A Comparative Study of Elderly Patients with Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder in Nursing Homes and the Community. Schizophrenia Research. 1997;27(no 2–3):181–190. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(97)00080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harvey PD. Schizophrenia in Late Life: Aging Effects on Symptoms and Course of Illness. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Linkins, et al. Screening for Mental Illness in Nursing Facility Applicants: Understanding Federal Requirements [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitchener M, et al. Home and Community-Based Services: Introduction to Olmstead Lawsuits and Olmstead Plans. San Francisco, CA: UCSF National Center for Personal Assistance Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ibid.

- 20.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services AdministrationCommunity Integration for Older Adults with Mental Illnesses: Overcoming Barriers and Seizing Opportunities. Rockville, MD: DHHS Pub. No. (SMA) 05-4018: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2004.

- 21.Colenda CC, Bartels SJ, Gottlieb GL. The United States System of Care. In: Copeland JRM, Abou-Saleh JT, Blazer DG, editors. Principles and Practices of Geriatric Psychiatry. New York: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knight BG, Kaskie B. Models for Mental Health Service Delivery to Older Adults. In: Gatz M, editor. Emerging Issues in Mental Health and Aging. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mor V, et al. Inter-Rater Reliability of Nursing Home Quality Indicators in the U.S. BMC Health Services Research. 2003;3(no 1):20. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-3-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harvey Schizophrenia in Late Life: Aging Effects on Symptoms and Course of Illness [Google Scholar]