Abstract

Objective The study examined individual differences between general practitioners (GPs) to determine their impact on variations in intention to refer a hypothetical patient with disordered eating to specialist eating disorder services. The study also examined the impact of patient weight on intention to refer.

Method GPs within three primary care trusts (PCTs) were posted a vignette depicting a patient with disordered eating, described as either normal weight or underweight. A questionnaire was developed from the theory of planned behaviour to assess the GPs' attitudes, perception of subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, and intention to refer the patient. Demographic details were also collected.

Results Responses were received from 88 GPs (33%). Intention to refer the patient was significantly related to subjective norms and cognitive attitudes. Together these predictors explained 86% of the variance in the intention to refer. GP or practice characteristics did not have a significant effect on the GPs' intention to refer, and nor did the patient's weight.

Conclusion Despite National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence current guidance, patient weight did not influence GPs' decisions to refer. Much of the variance in actual referral behaviour may be explained by cognitive attitudes and subjective norms. Interventions to reduce this variation should be focused on informing GPs about actual norms, and best practice guidelines.

Keywords: decision making, eating disorders, referral

Introduction

The National Service Framework for Mental Health recognises that eating disorders are among the three most common mental health problems.1 Anorexia nervosa (AN) and bulimia nervosa (BN) are prevalent in 0.3% and 1% of young women respectively,2 with up to twice this many people affected by disordered eating that does not fit these stringent diagnostic criteria.3 Research suggests that rates of eating disorders are increasing.4

Primary care has an important role in identifying eating disorders.5 Early diagnosis and intervention are related to better prognosis for eating-disordered patients.6 Most patients make their first contact with their GP, and patients with eating disorders consult their general practitioner (GP) more frequently than controls.5 The current National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines for eating disorders make separate recommendations for the treatment of AN and BN. The guidance recommends that GPs should initially assess and coordinate the care of patients with AN, and that treatment should be offered at the earliest opportunity, especially in individuals of lower weight,7 which will usually mean referral to a specialist. GPs are more confident in detecting than managing eating disorders.8 However, many cases of disordered eating are managed primarily in primary care, with around a quarter of cases managed exclusively in primary care.9

There is a wide variation in the number of patients referred to specialist services.10 The Department of Health suggests that such variation in service provision should be reduced.1 Previous research has identified GP and practice factors associated with the variation in referral rates.10 The referral decisions of GPs are important because they have an impact on the care their patients receive and the demands on psychological services.11 Most of the variation in referral rates remains unexplained.10 Individual differences between GPs' attitudes and beliefs may be important determinants of this variation.

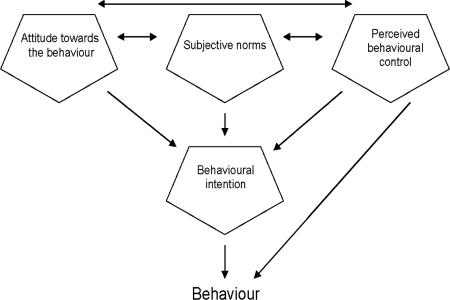

This study aimed to examine the beliefs and attitudes of GPs and how these influence referral behaviour for eating disorders. It also aimed to examine the effect of patient weight (normal or low) at presentation on the GPs' referral behaviour. The theory of planned behaviour (TPB) was used to look at how GPs responded to patient vignettes.12 The TPB considers the combination of three types of belief: attitudes towards the behaviour, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control. Attitudes include both the individual's cognitive and emotional beliefs about the outcome of their behaviour and their positive and negative evaluation of the behaviour. Subjective norms are influenced by the perceived usual behaviour of others, the perceived pressure to comply with that behaviour, and the individual's motivation to comply. Finally, perceived behavioural control is a combination of whether an individual has the skills required to carry out the behaviour and the expected external constraints on carrying out the behaviour. The TPB states that these beliefs predict behavioural intention, which is linked to behaviour (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The theory of planned behaviour

Method

Southampton and South West Hampshire NHS Ethics Committee approved the study and Trust R&D approvals were granted. A cross-sectional postal survey was conducted with all 267 GPs included in the published lists of three primary care trusts (PCTs; Blackwater Valley and Hart, North Hants and Mid Hants). Each practitioner was sent an invitation letter, a vignette and a questionnaire, along with an information sheet.

The vignette was developed from clinical experience, depicting an 18-year-old female presenting to discuss travel immunisations. The vignette described disordered eating patterns, but was designed to be equivocal as to whether referral would be advocated by current guidelines. Two versions of the vignette were used, which differed only in their description of the patient's weight. In half the vignettes the patient was of normal weight (body mass index (BMI) of 21.9 kg/m2) and in half underweight (BMI of 17.1 kg/m2). Each version of the vignette was sent out to half of the GPs, allocated using random number tables.

The questionnaire was developed using a manual for constructing questionnaires according to the theory of planned behaviour,13 to determine the GP attitudes and beliefs about the patient and possible referral described in the vignette. This questionnaire was informed by interviews with GPs about eating disorders, conducted as part of a separate qualitative study, led by OJ. Responses were recorded on a Likert scale measuring the GPs' attitudes: including cognitive attitudes (how sensible/appropriate/helpful would referral be?); emotional attitudes (how satisfied/pleased/relieved would referral make the GP feel?); beliefs (referral is necessary/stigmatising/increases dependency/decreases relapse); subjective norms (would other professionals/guidelines/evidence recommend referral?); and perceived control (referral decision would be possible/accepted/accurate). Items were also included to measure the GPs' intention to refer the patient, and demographic information regarding the GP and practice (sex, age, years in practice, training status, practice size and practice services). The questionnaire was piloted on a sample of five primary care clinicians. Non-responding GPs were sent a reminder letter after three weeks.

The data were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 12.0.2. The significance of factors associated with the intention to refer was explored using descriptive statistics, and a Mann-Whitney U test was used to determine factors that were correlated with intention to refer the patient. These factors were then entered into a multiple linear regression analysis. A multivariate analysis of variance was used to determine impact of demographic factors on intention to refer.

Results

Responses were received from 88 of the 267 GPs (33%). Of the respondents, 48 (55%) were female. One questionnaire was returned incomplete. The GPs had practised for a mean of 15 years. Around half the GPs (44) worked in an urban/suburban practice and half in rural settings. Around two-thirds (58) of the GPs had specialist psychiatric experience. Of the questionnaires returned, 45 concerned the underweight patient, and 43 concerned the normal-weight patient.

On the seven-point Likert scale, responses were grouped into ‘positive’ (score of 5–7), ‘ambivalent’ (score of 4) and ‘negative’ (score of 1–3).

GP demographics

A multivariate analysis of variance determined that none of the GP or practice characteristics had a significant effect on the GPs' intention to refer at the 5% level of significance.

Patient weight

The weight of the patient did not have a significant impact on the decision to refer. However, the lower-weight vignette was associated with a higher perceived behavioural control regarding referral (median of 4.76 versus 4.17, P = 0.018 Mann-Whitney U)

GP responses

Agreement to statements reflecting attitudes, beliefs, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control and intention to refer are shown in Table 1. GPs' cognitive attitudes were on the positive side towards referral, though when looking at emotional attitudes, GPs were less positive. GP sex had a significant effect on emotional attitudes: female GPs were more positive in their emotional attitudes towards referral (4.17 versus 4.31, P = 1.134 Mann-Whitney U). Responses to questions about the GPs' beliefs were often ambivalent; the strongest responses are displayed in Table 1. Forward multiple linear regression showed that none of the beliefs were individual predictors of intention to refer. Furthermore, neither GPs' feeling of control over referral, nor whether the GPs' felt that they had the necessary referral skills were found to be related to intention to refer the patient (Spearman's correlation coefficient r = −0.05, P = 0.678, and r = −0.03, P = 0.806 respectively). Intention to refer the patient was significantly related to subjective norms and cognitive attitudes (Spearman's correlation coefficients r = 0.917 and 0.896 respectively, P < 0.001). Together, these predictors explained 86% of the variance in the intention to refer (R2 = 0.86, P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Agreement of GPs to questionnaire items

| Item | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Attitudes | ||

| Cognitive attitudes | ||

| Referral would be sensible | 50 | 57 |

| Referral would be appropriate | 48 | 55 |

| Referral would be helpful | 49 | 55 |

| Emotional attitudes | ||

| Referring the patient would make me feel satisfied | 40 | 45 |

| Referring the patient would make me feel relieved | 44 | 50 |

| Referring the patient would make me feel pleased | 32 | 36 |

| Beliefs | ||

| The patient won't recover unless they are referred to secondary care | 14 | 16 |

| Referral would compensate for my limitations in managing eating disorders | 51 | 58 |

| Referral is likely to reduce the risk to their health | 52 | 59 |

| Subjective norms; referral to secondary care would be recommended by… | ||

| Primary care nursing colleagues | 38 | 43 |

| Local GP colleagues | 41 | 47 |

| Local consultant psychiatrist(s) colleagues | 43 | 49 |

| Current good practice guidelines | 51 | 58 |

| Best available research evidence | 50 | 56 |

| Perceived behavioural control | ||

| I would have complete control over whether I refer the patient | 44 | 50 |

| I have the skills needed to raise the issue of whether I should refer the patient to secondary care | 78 | 89 |

| Intention to refer | ||

| I would refer the patient to secondary care | 48 | 55 |

Discussion

This study suggests that a significant proportion of the variation in referral for eating disorders is explained by the cognitive attitudes and subjective norms of GPs. Surprisingly, despite the NICE guidance recommendations that patients of low BMI should be prioritised for treatment,7 the weight of the patient did not make a significant difference to the decision to refer. This finding concurs with a previous study which showed that weight status did not influence the likelihood of referral to secondary care.15

This outcome may be explained by the self-selected sample of GPs who responded to the postal survey. This sample may have been especially interested in managing disordered eating, and therefore the BMI of the low-weight patient was perhaps less likely to trigger a decision to refer. Analysis of the GPs' perceived behavioural control showed that GPs were confident in their skills related to referring the patient, which would tend to support this explanation.

Another surprising finding was that the GP demographic and practice factors were not associated with the GPs' referral behaviour. This contradicts previous findings that female sex, being UK qualified, offering full contraceptive services, and shorter distance of the practice from a specialist centre were all associated with increased referral to an eating disorder service.10

Strengths and limitations

The vignette approach was a useful method to use, especially in eating disorders, where new case presentations are rare,14 which makes it difficult to base an exploration of attitudes on a recent real-life case. This approach made it possible to study a relatively large number of respondents in a short time. However, the vignette approach means that the study could only explore intention to refer a hypothetical case. Although intention is a strong predictor of behaviour, it is not the same thing. This may partially explain differences between the outcomes in this study and those in previous research on actual referral rates.

Another strength of the study was its theoretical basis, employing the TPB as a means of getting at the GPs' underlying attitude and belief structures, rather than simply asking them about their opinions in a less structured and theoretically based way, as has been done previously.15 The questionnaire used was devised according to a published manual, ensuring that the main aspects of the TPB were reflected. Development of the questionnaire was informed by existing literature and interviews with GPs, maximising the relevance and face validity to GPs. The questionnaire was kept as short as possible and piloted on a sample of primary care clinicians, to maximise acceptability to busy practitioners. However, due to the low response rate, the sample size for this study was smaller than anticipated. This means that the results need interpreting with caution as some relationships may not have been identified due to a lack of power. However, the number of responses was sufficient to carry out the planned analysis and identify some significant associations. Also, the responding GPs were from a variety of locations and years of practice, which tends to increase the generalisability of the findings.

It is not clear from this study on what the cognitive attitudes regarding referral are based. Further research might use a qualitative approach to explore the development of these cognitive attitudes. Future research may also benefit from using larger and more representative samples, or from using real-life examples, presented through videotaped recordings, or remembered from GPs' own experience.

GP referral behaviour seems to an extent to be explained by subjective norms and cognitive attitudes. This reinforces the need for interventions to reduce variations in referral, in accordance with the NICE guidance.7 As GPs report beliefs that their referral behaviour in the majority of cases is in line with that of colleagues and that recommended in guidelines, it must follow that their perceptions cannot always be accurate, as in reality their behaviour as a group varies widely. Therefore, by informing GPs, giving them more information about the actual norms of referral rates and guidelines on when referral is indicated, the wide variation in referral rates could be reduced in a rational way.

Contributor Information

Helen Green, Clinical Psychologist in Training.

Olwyn Johnston, Clinical Psychologist.

Sara Cabrini, GP Trainee.

Gemma Fornai, GP Trainee.

Tony Kendrick, Professor of Primary Medical Care, Primary Medical Care Group, University of Southampton, UK.

REFERENCES

- 1.Department of Health National Service Framework for Mental Health: modern standards and service models London: Department of Health, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoek HW, van Hoeken D. Review of the prevalence and incidence of eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders 2003;34:383–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitehouse AM, Cooper PJ, Vize CV, et al. Prevalence of eating disorders in three Cambridge general practices: hidden and conspicuous morbidity. British Journal of General Practice 1992;42:57–60 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turnbull S, Ward A, Treasure J, et al. The demand for eating disorder care. An epidemiological study using the general practice research database. British Journal of Psychiatry 1996;169:705–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogg EC, Millar HR, Pusztai EE, et al. General practice consultation patterns preceding diagnosis of eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders 1997;22:89–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pritts SD, Susman J. Diagnosis of eating disorders in primary care. American Family Physician 2003;67:297–304, 311–12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Institute for Clinical Excellence Eating Disorders: core interventions in the treatment and management of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and related eating disorders London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boule CJ, McSherry JA. Patients with eating disorders. How well are family physicians managing them? Canadian Family Physician 2002;48:1807–13 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graham J. News Extra. GPs are dissatisfied with the care they are giving patients with eating disorders. British Medical Journal 2005;330:336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hugo P, Kendrick T, Reid F, et al. GP referral to an eating disorder service: why the wide variation? British Journal of General Practice 2000;50:380–3 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ross H, Hardy G. GP referrals to adult psychological services: a research agenda for promoting needs–led practice through the involvement of mental health clinicians. British Journal of Medical Psychology 1999;72:75–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fishbein M, Azjen I.(1975)Belief Attitude, Intention and Behaviour: an introduction to theory and research Reading MA: Addison-Wesley, 1975 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Francis JJ, Eccles MP, Johnston M, et al. Constructing Questionnaires Based on The Theory of Planned Behaviour: a manual for health services researchers Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Centre for Health Services Research, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Betancourt JR. Cross-cultural medical education: conceptual approaches and frameworks for evaluation. Academic Medicine 2003;78:560–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Currin L, Schmidt U, Waller G.Variables that influence diagnosis and treatment of the eating disorders within primary care settings: a vignette study. International Journal of Eating Disorders 2007;40:257–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

This work was conducted while OJ was in receipt of a postdoctoral fellowship from the Health Foundation and the DH/NCC RCD Programme.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None.